Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), c. 1123, outside the village of Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain (photo:

Map of the Vall de Boí, a valley nestled within the Pyrenees mountains in the Catalonia region of north-east Spain

Medieval travelers through the Vall de Boí, a valley nestled within the Pyrenees mountains in the Catalonia region of Spain, encountered a towering terrain dotted with rural village churches. Built or rebuilt between the eleventh and twelfth centuries, these small stone churches have similar architectural features (for example, square multi-story bell towers). In contrast to the churches’ humble exteriors, the interiors contained striking painted programs. The wall painting of Christ in Majesty in the central apse of the church of Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), outside the village of Taüll, is the most outstanding example from the Boí valley. The smaller apses on either side were also brightly painted.

The paintings are frescoes: the composition was marked into the fresh plaster and layers of paint were applied. When the wall dried, further details were added.

Interior, with a focus on the central apse. Faint traces of the Christ in Majesty fresco are visible, c. 1123, Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), outside the village of Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain (photo: Anabelle Gambert-Jouan)

What did medieval people see when they entered Sant Climent?

A few windows dimly illuminated the modestly-sized interior of Sant Climent. From the shadows, paintings in bold colors, bright blues, reds, yellows, and greens would appear, covering the walls, arranged against a background of broad horizontal bands. The most striking image was located in the central apse, the semicircular space behind the altar. There, the medieval viewer saw the monumental image of the Maiestas Domini or Christ in Majesty looking down towards the churchgoer. A scene of Christ in Majesty typically shows Christ seated on a throne surrounded by the symbols of the four Evangelists (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). The Christ in Majesty and the accompanying painting program in this apse conveyed complex theological ideas through figurative imagery and symbols from the Book of Revelation (the last book of the Christian Bible), as well as visions of Old Testament prophets.

Mapping Sant Climent de Taüll from Mapping Sant Climent de Taüll on Vimeo

Today, the original paintings are no longer inside the church, although some ghostly traces remain. At one point, reproductions of the paintings were inside the church. Nowadays, visitors are treated to a video projection onto the walls that conveys some of the image program’s former glory.

Christ in Majesty, c. 1123, fresco, originally in the central apse in Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), outside the village of Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain, today in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Column with painted inscription, c. 1123, Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), outside the village of Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain, today in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (photo: Anabelle Gambert-Jouan)

Today, Christ in Majesty and the majority of paintings from Sant Climent are preserved in the National Museum of Art of Catalonia, in Barcelona where the main sections of the church’s interior structure are recreated as a support for the relocated frescos. The display includes the frescoes from the central apse, a row of angels from the north apse, and a Latin inscription painted on a column in commemoration of the consecration of the church in 1123.

The artists who painted the church of Sant Climent are not known but, traditionally, art historians refer to the painter of the central apse as the “Master of Taüll.” Scholars have determined that the angels in the north apse are by another hand, since they have a more rudimentary quality.

Christ in Majesty, c. 1123, fresco, originally in Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), outside the village of Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain, today in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

A vision of Revelation and the end of time

At Sant Climent, Christ hovers above the altar as he sits on a band decorated with gold foliate motifs inside a blue mandorla. Christ’s head is framed by a bright white halo, his facial features elongated and symmetrical. He looks forward and raises his right hand in a gesture of blessing. In his left hand, Christ holds an open book revealing the words “EGO SUM LUX MUNDI” (“I am the light of the world”) from the Gospel of John, written in capital letters. The Greek letters “Alpha” and “Omega” are painted in white on each side of Christ’s shoulders (the letters refer to the Book of Revelation where Christ describes himself as “the Alpha and the Omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end” to express his all-encompassing nature).

Christ in Majesty, c. 1123, fresco, originally in Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), outside the village of Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain, today in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Christ is surrounded by the tetramorph representing the four Evangelists. The symbols are the Lion for Mark, the Ox for Luke (presented by angels in roundels or round frames), the Eagle for John (presented by a standing angel), and an Angel for Matthew.

The program at Sant Climent also draws on the apocalyptic visions of Old Testament prophets. According to the Old Testament, Ezekiel saw the “likeness of four living creatures” (the symbols of the Evangelists) bearing God’s chariot, and Isaiah saw the “Lord sitting upon a throne” with two seraphim (celestial beings with six wings). Elements of these visions, such as the symbols of the Evangelists and the seraphim, are represented in the apse at Sant Climent. In addition, two roundels, each in an arch preceding the apse (see image below), contain pictorial representations of the Hand of God and the Lamb of the Apocalypse (a lamb with seven eyes described in the Book of Revelation). Apocalyptic imagery—imagery that described the end of the world as told in the Book of Revelation—was popular in Romanesque art of southern Europe, such as we see in places like the Church of St. Pierre, Moissac.

Dynamism and movement in monumental painting

At Sant Climent in Taüll, the artist understood how the curved space of the apse affected the appearance and visual impact of images there. If the Christ in Majesty had been painted on a flat surface, Christ’s lower body would have appeared much smaller than his upper body. However, in the concave space of the apse, Christ appears more proportional. Although Christ sits in a frontal pose, he is not static, as the draperies swell around his knees and elbows. This unique visual effect was achieved by adding bright blue and white paint on top of black for the mantle and tunic. The alternating thick and thin black lines on Christ’s blue mantle and the white highlights on his gray tunic help to create the illusion of movement.

An angel reaching for the leg of a winged lion, symbol of St. Mark. The eyes on the winged lion come from a reference in the Book of Revelation. Christ in Majesty (detail), fresco, originally in Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), outside the village of Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain, today in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The painter also experimented with the relationship of figures to their frames. Christ’s right hand, his feet, and his halo extend past the outline of the mandorla that surrounds Christ’s body. Beneath Christ, the medallions containing half-length angels do not appear as flat circles but as volumetric rings that maintain their spherical shape against the curved recess of the apse. This is achieved through the shading of the inner and outer faces of the rings in complementary blue and gold tones. The angels break from their frames to reach the leg of a lion (Mark) and the tail of an ox (Luke). Although the angels appear stern, the interplay with the animals illustrates how Romanesque art is able to combine seriousness and playfulness.

Christ in Majesty, fresco, originally in Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), outside the village of Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain, today in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Master of La Seu d’Urgell, from the central apse from Sant Pere de La Seu d’Urgell, second quarter of the 12th century, fresco, Spain, 720 x 500 x 260 cm, now in the Museu Nacional d’art de Catalunya

Beneath Christ in Majesty are Christ’s apostles and the Virgin Mary, who stand between columns with arches above. The inclusion of standing figures beneath a monumental image of Christ or the Virgin Mary in an apse or dome derives from Byzantine art. Traveling artists from Byzantium promoted this representational form, which was adopted initially in the Italian peninsula, and spread to Romanesque wall painting across Western Europe, including Catalonia. In Catalonia, other examples can be found in the apses from Sant Pere (Saint Peter in Catalan), La Seu d’Urgell, and Santa Maria de Mur.

At Sant Climent, the standing figures are identified by their name in the band above their heads. Some painting fragments from additional figures like Peter, Cornelius, and Clement have been recovered and are currently visible inside the church (not pictured here). The Virgin Mary, near the central window, holds a vessel containing red liquid from which fine red rays emerge. This represents the blood of Christ, which in the church environment has a Eucharistic meaning.

Left: Master of Pedret, Apse of Sant Pere, El Burgal, end of 11th century–beginning of 12th century, fresco, 670 x 400 x 200 cm, now in the Museu Nacional d’art de Catalunya; right: Female figure or saint (the Virgin Mary?), c. 1125, wood with traces of polychrome and gesso, 145.1 x 35.6 x 30.2 cm, found behind the altar of the church of Santa Maria de Taüll in Catalonia, Spain, now in the Harvard Art Museum

This attribute appears in other twelfth-century paintings of the Virgin Mary in the Pyrenees, for example in the apse of Sant Pere, El Burgal. Similarly, a wood sculpture of a holy woman made for one of the churches in Taüll shares the Sant Climent Virgin’s round headdress and elongated facial features.

Christ in Majesty, with images of the hand of God and the lamb of the apocalypse above, fresco, originally in Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), outside the village of Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain, today in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (photo: Anabelle Gambert-Jouan)

Narrative scenes

The program on the arches preceding the apse contained primarily narrative scenes, however many do not survive. The best-preserved image comes from a parable told by Jesus.

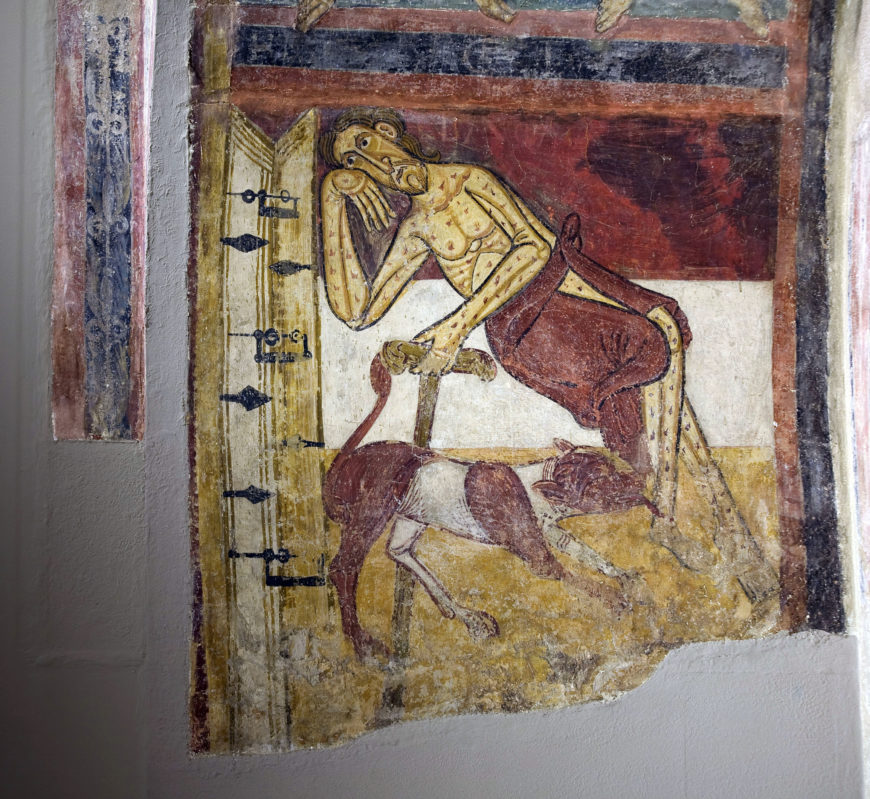

Detail of Lazarus, fresco, originally in Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), outside the village of Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain, today in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

It shows the beggar Lazarus laying on his side, languishing in front of a door which is bolted shut while a dog licks his sores. The door belongs to a rich man who refused to allow Lazarus to eat at his table. Parts of the table, richly adorned with golden vessels, can be seen on the opposite side of the arch inside the church. Ultimately, the rich man goes to hell for his actions, while Lazarus goes to heaven.

Detail of Cain, fresco, originally in Sant Climent (Saint Clement in Catalan), outside the village of Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain, today in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Other scenes dealt with similar themes of Redemption and Fall. Next to Lazarus, on the arch closest to the central apse, Cain sits holding his head in his hand. His downturned eyes and mouth show his sorrow and anger after God rejected his offering and accepted only that of his brother Abel. Remnants of the image of the tragic aftermath—Cain’s killing of Abel—are visible in situ (still on location in the church), on the opposite side of the arch.

From the medieval church to the modern museum

Although the Boí valley was fairly isolated because of its geographic location in the Pyrenees, in the Middle Ages the mountain range was one of the main ways of accessing the Iberian peninsula, today Spain and Portugal, from the rest of Europe (another option was by sea). Due to this location at the crossroads of Romanesque Europe, artists and architects came to the region from across the Iberian Peninsula, as well as from France and Italy, as attested by the Lombard (North-Italian) style of the Sant Climent bell tower (visible in the photograph at the top of the essay). This artistic convergence can also be seen in the materials used in the frescoes. Some pigments came from local sources in the Pyrenees, while others were imported, like cinnabar that came from Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain).

Sant Climent’s consecration is recorded in 1123 (see the image of the column with the commemorative inscription above). However, there is no documentation about the church’s earlier foundation and construction. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Boí valley was ruled by the lords of Erill, local feudal lords who had gained wealth and status through their participation in the Spanish Reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula. The lords of Erill fought for the king of Aragón, alongside Christian forces, to capture important cities like Zaragoza, which had been under Muslim control since the eight century. The wealth accrued by the lords of Erill seems to have motivated their patronage of religious art and architecture in villages across the Boí valley. Their patronage included the building or rebuilding of Boí valley churches like Sant Climent. Although little is known about how these churches were used in the twelfth century, it was customary for village communities in the Pyrenees to have one or more churches intended for use by local inhabitants.

Central apse painting with Virgin and Child Enthroned, c. 1123, church of Santa Maria de Taüll, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain,, today in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Animal figure, c. 1100, 240 x 106 cm, church of Sant Joan (John in Catalan) de Boí, Vall de Boí, Alta Ribagorça, Spain, today in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Churches throughout the Pyrenees in Catalonia are now recognized and renowned for some of the best preserved examples of twelfth-century European monumental wall painting, like the San Climent Christ in Majesty. In the Boí valley, wall paintings survive from the neighboring churches of Sant Joan, Boí, and Santa Maria, also in Taüll. They show scenes from the Old and New Testaments and, in the case of Sant Joan, include depictions of real and imaginary animals, similar to medieval bestiaries.

Many twelfth-century wall-paintings from Pyrenees churches, including San Climent, are now housed at the National Museum of Art of Catalonia. The apse paintings were removed from Sant Climent in the 1920s using a technique called “strappo” that allowed experts to pull the thin painted layer of plaster off the wall so that it could be transferred to canvas without damaging the images. This was done at Sant Climent and in other Catalan churches after monumental Romanesque paintings had been stripped from the walls of other churches and sold on the international art market. In the museum, the Christ in Majesty from Sant Climent has become an icon of Romanesque art. In 1934, the painter Pablo Picasso visited the National Museum of Art of Catalonia, and became enamored with the Sant Climent wall paintings, even producing a tile painting based on the Christ in Majesty (now in a private collection). Since the Middle Ages, the wall paintings from Sant Climent, Taull have dazzled, enchanted, and captured the imaginations of visitors from across the world.