Origins and the life of Muhammad the Prophet

Islam, Judaism, and Christianity are three of the world’s great monotheistic faiths. They share many of the same holy sites, such as Jerusalem, and prophets, such as Abraham. Collectively, scholars refer to these three religions as the Abrahamic faiths, since Abraham and his family played vital roles in the formation of these religions.

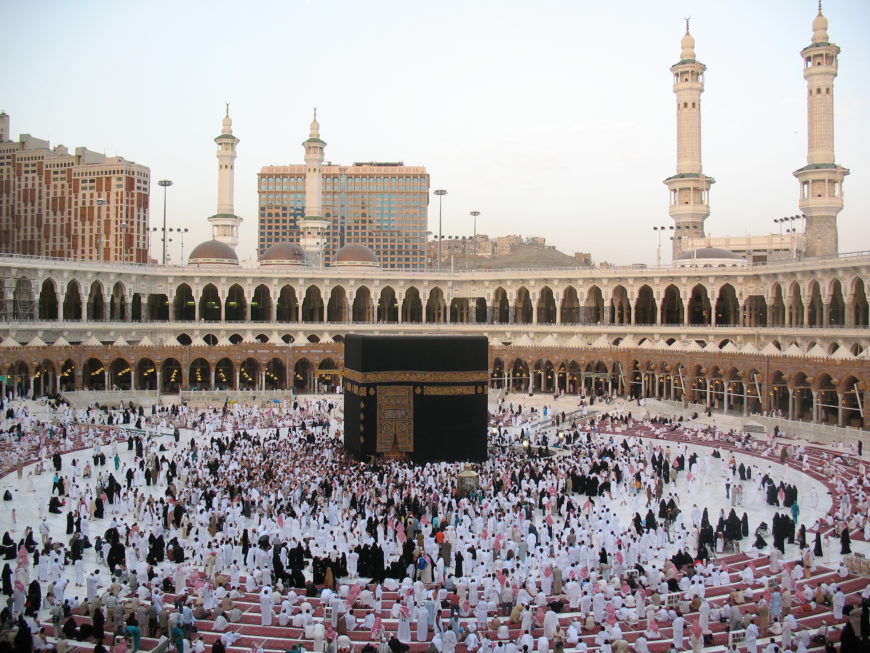

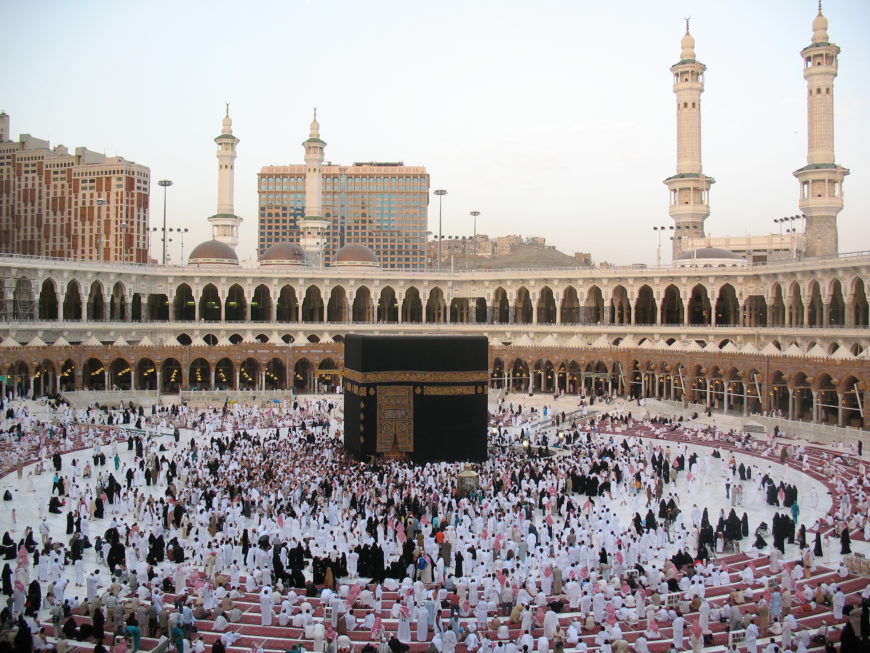

The Kaaba, granite masonry, covered with silk curtain and calligraphy in gold and silver-wrapped thread, pre-Islamic monument, rededicated by Muhammad in 631–32 C.E., multiple renovations, Mecca, Saudi Arabia (photo: marviikad, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Islam was founded by Muhammad (c. 570–632 C.E.), a merchant from the city of Mecca, now in modern-day Saudi Arabia. Mecca was a well-established trading city. The Kaaba (in Mecca) is the focus of pilgrimage for Muslims.

The Qur’an, the holy book of Islam, provides very little detail about Muhammad’s life; however, the hadiths, or sayings of the Prophet, which were largely compiled in the centuries following Muhammad’s death, provide a larger narrative for the events in his life. Muhammad was born in 570 C.E. in Mecca, and his early life was unremarkable. He married a wealthy widow named Khadija. Around 610 C.E., Muhammad had his first religious experience, where he was instructed to recite by the Angel Gabriel. After a period of introspection and self-doubt, Muhammad accepted his role as God’s prophet and began to preach word of the one God, or Allah in Arabic. His first convert was his wife.

Muhammad’s divine recitations form the Qur’an; unlike the Bible or Hindu epics, it is organized into verses, known as ayat. During one of his many visions, in 621 C.E., Muhammad was taken on the famous Night Journey by the Angel Gabriel, travelling from Mecca to the farthest mosque in Jerusalem, from where he ascended into heaven. The site of his ascension is believed to be the stone around which the Dome of the Rock was built. Eventually in 622, Muhammad and his followers fled Mecca for the city of Yathrib, which is known as Medina today, where his community was welcomed. This event is known as the hijra, or emigration. 622, the year of the hijra (A.H.), marks the beginning of the Muslim calendar, which is still in use today.

Between 625–630 C.E., there were a series of battles fought between the Meccans and Muhammad and the new Muslim community. Eventually, Muhammad was victorious and reentered Mecca in 630.

One of Muhammad’s first actions was to purge the Kaaba of all of its idols (before this, the Kaaba was a major site of pilgrimage for the polytheistic religious traditions of the Arabian Peninsula and contained numerous idols of pagan gods). The Kaaba is believed to have been built by Abraham (or Ibrahim as he is known in Arabic) and his son, Ishmael. The Arabs claim descent from Ishmael, the son of Abraham and Hagar. The Kaaba then became the most important center for pilgrimage in Islam.

In 632, Muhammad died in Medina. Muslims believe that he was the final in a line of prophets, which included Moses, Abraham, and Jesus.

After Muhammad’s death

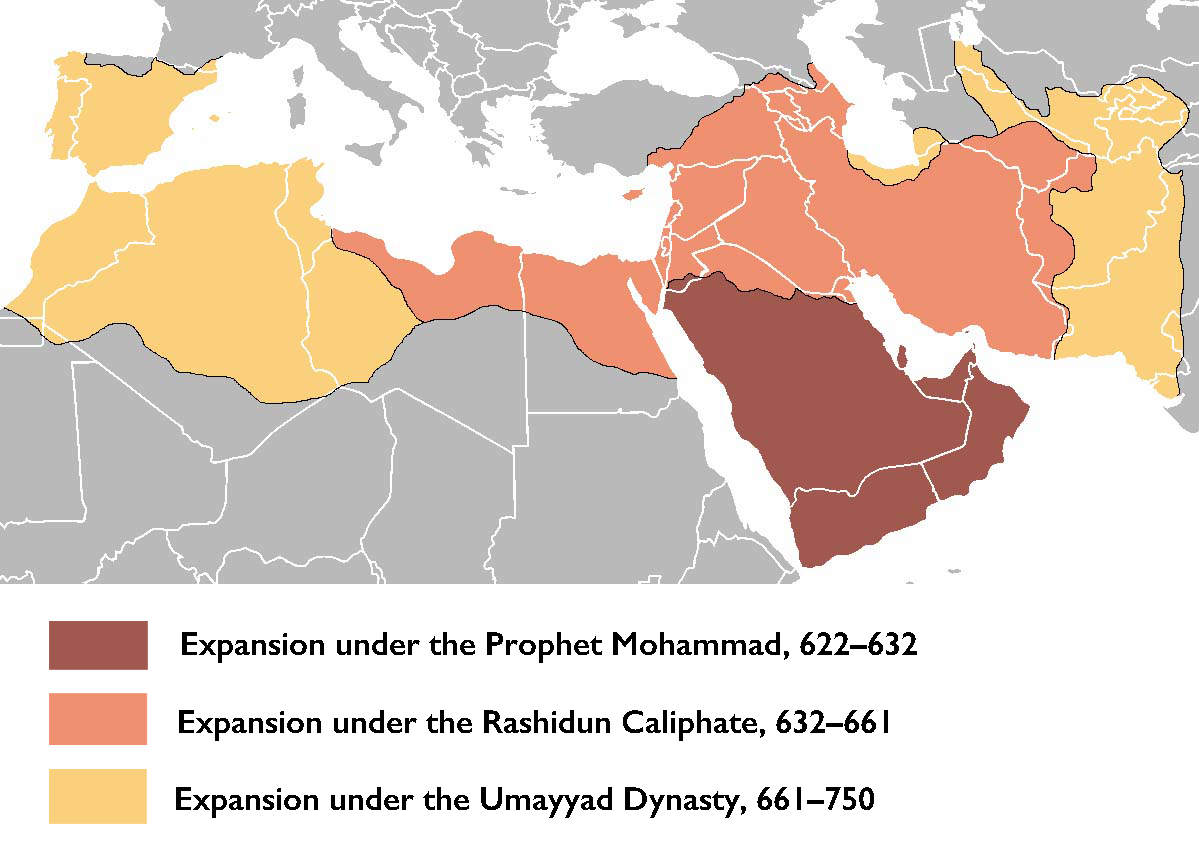

The century following Muhammad’s death was dominated by military conquest and expansion. Muhammad was succeeded by the four “rightly-guided” Caliphs (khalifa or successor in Arabic): Abu Bakr (632–34 C.E.), Umar (634–44 C.E.), Uthman (644–56 C.E.), and Ali (656–661 C.E.). The Qur’an is believed to have been codified during Uthman’s reign. The final caliph, Ali, was married to Fatima, Muhammad’s daughter and was murdered in 661. The death of Ali is a very important event; his followers, who believed that he should have succeeded Muhammad directly, became known as the Shi’a, meaning the followers of Ali. Today, the Shi’ite community is composed of several different branches, and there are large Shi’a populations in Iran, Iraq, and Bahrain. The Sunnis, who do not hold that Ali should have directly succeeded Muhammad, compose the largest branch of Islam; their adherents can be found across North Africa, the Middle East, as well as in Asia and Europe.

The Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra), Umayyad, stone masonry, wooden roof, decorated with glazed ceramic tile, mosaics, and gilt aluminum and bronze dome, 691–92, with multiple renovations, patron the Caliph Abd al-Malik, Jerusalem (photo: Brian Jeffery Beggerly, CC BY 2.0)

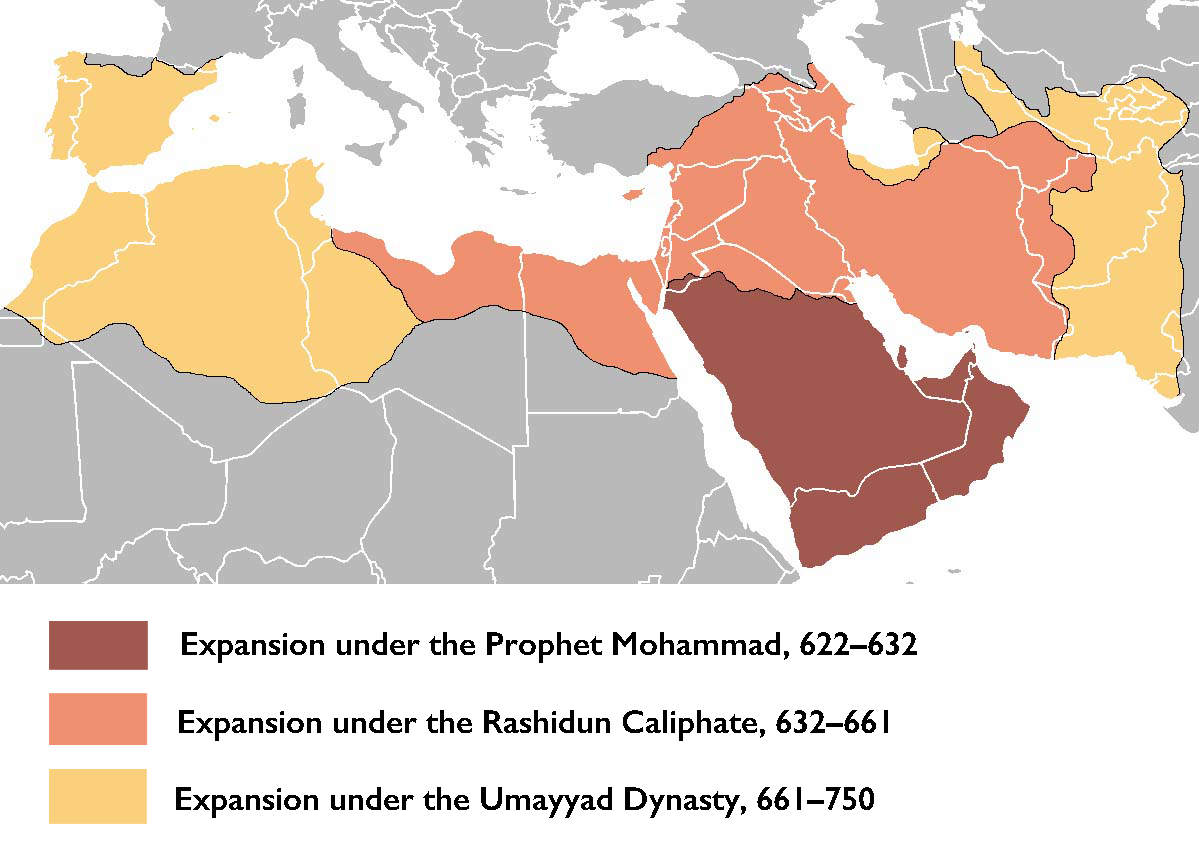

During the seventh and early eighth centuries, the Arab armies conquered large swaths of territory in the Middle East, North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and Central Asia, despite on-going civil wars in Arabia and the Middle East. Eventually, the Umayyad Dynasty emerged as the rulers, with Abd al-Malik completing the Dome of the Rock, one of the earliest surviving Islamic monuments, in 691/2 C.E. The Umayyads reigned until 749/50 C.E., when they were overthrown, and the Abbasid Dynasty assumed the Caliphate and ruled large sections of the Islamic world. However, with the Abbasid Revolution, no one ruler would ever again control all of the Islamic lands.

Additional resources

The Birth of Islam on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

World Religions in Art: Islam (from the Minneapolis Museum of Art)

BBC Article on the Sunni and Shi’a

Cite this page as: Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay, “Introduction to Islam,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed July 29, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-islam/.

The caliphates

The umbrella term “Islamic art” casts a pretty big shadow, covering several continents and more than a dozen centuries. So to make sense of it, we first have to first break it down into parts. One way is by medium—say, ceramics or architecture—but this method of categorization would entail looking at works that span three continents. Geography is another means of organization, but modern political boundaries rarely match the borders of past Islamic states.

A common solution is to consider instead, the historical caliphates (the states ruled by those who claimed legitimate Islamic rule) or dynasties. Though these distinctions are helpful, it is important to bear in mind that these are not discrete groups that produced one particular style of artwork. Artists throughout the centuries have been affected by the exchange of goods and ideas and have been influenced by one another.

Umayyad (661–750)

Four leaders, known as the Rightly Guided Caliphs, continued the spread of Islam immediately following the death of the Prophet. It was following the death of the fourth caliph that Mu’awiya seized power and established the Umayyad caliphate, the first Islamic dynasty. During this period, Damascus became the capital and the empire expanded West and East.

The first years following the death of Muhammad were, of course, formative for the religion and its artwork. The immediate needs of the religion included places to worship (mosques) and holy books (Korans) to convey the word of God. So, naturally, many of the first artistic projects included ornamented mosques where the faithful could gather and Korans with beautiful calligraphy.

Because Islam was still a very new religion, it had no artistic vocabulary of its own, and its earliest work was heavily influenced by older styles in the region. Chief among these sources were the Coptic tradition of present-day Egypt and Syria, with its scrolling vines and geometric motifs, Sasanian metalwork and crafts from what is now Iraq with their rhythmic, sometimes abstracted qualities, and naturalistic Byzantine mosaics depicting animals and plants.

The Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra), Umayyad, stone masonry, wooden roof, decorated with glazed ceramic tile, mosaics, and gilt aluminum and bronze dome, 691–92, with multiple renovations, patron the Caliph Abd al-Malik, Jerusalem (photo: Brian Jeffery Beggerly, CC BY 2.0)

These elements can be seen in the earliest significant work from the Umayyad period, the most important of which is the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. This stunning monument incorporates Coptic, Sasanian, and Byzantine elements in its decorative program and remains a masterpiece of Islamic architecture to this day.

Remarkably, just one generation after the religion’s inception, Islamic civilization had produced a magnificent, if singular, monument. While the Dome of the Rock is considered an influential work, it bears little resemblance to the multitude of mosques created throughout the rest of the caliphate. It is important to point out that the Dome of the Rock is not a mosque. A more common plan, based on the house of the Prophet, was used for the vast majority of mosques throughout the Arab peninsula and the Maghreb. Perhaps the most remarkable of these is the Great Mosque of Córdoba (784–786) in Spain, which, like the Dome of the Rock, demonstrates an integration of the styles of the existing culture in which it was created.

Mihrab dome, Great Mosque at Cordoba, Spain (photo: José Luiz, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Abbasid (750–1258)

Territory of the Abbasid Caliphate at its greatest extent (green), c. 850

The Abbasid revolution in the mid-eighth century ended the Umayyad dynasty, resulted in the massacre of the Umayyad caliphs (a single caliph escaped to Spain, prolonging Umayyad work after dynasty) and established the Abbasid dynasty in 750. The new caliphate shifted its attention eastward and established cultural and commercial capitals at Baghdad and Samarra.

The Umayyad dynasty produced little of what we would consider decorative arts (like pottery, glass, metalwork), but under the Abbasid dynasty production of decorative stone, wood and ceramic objects flourished. Artisans in Samarra developed a new method for carving surfaces that allowed for curved, vegetal forms (called arabesques) which became widely adopted. There were also developments in ceramic decoration. The use of luster painting (which gives ceramic ware a metallic sheen) became popular in surrounding regions and was extensively used on tile for centuries. Overall, the Abbasid epoch was an important transitional period that disseminated styles and techniques to distant Islamic lands.

The Abbasid empire weakened with the establishment and growing power of semi-autonomous dynasties throughout the region, until Baghdad was finally overthrown in 1258. This dissolution signified not only the end of a dynasty, but marked the last time that the Arab-Muslim empire would be united as one entity.

Additional resources

Read about the Umayyads

Read the vibrant visual cultures of the Islamic West, an introduction

The Art of the Umayyad Period (661–750) from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

The Nature of Islamic Art from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Elizabeth Dospěl Williams, “Craft and Aesthetics in Byzantine and Early Islamic Textiles,” Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online, October 19, 2020.

Cite this page as: Glenna Barlow, “Arts of the Islamic world: The early period,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed July 29, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/arts-of-the-islamic-world-the-early-period/.

The Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra), Jerusalem, 691–92 (Umayyad), stone masonry, wooden roof, decorated with glazed ceramic tile, mosaics, and gilt aluminum and bronze dome, with multiple renovations, patron the Caliph Abd al-Malik (photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0)

The Dome of the Rock is a building of extraordinary beauty, solidity, elegance, and singularity of shape… Both outside and inside, the decoration is so magnificent and the workmanship so surpassing as to defy description. The greater part is covered with gold so that the eyes of one who gazes on its beauties are dazzled by its brilliance, now glowing like a mass of light, now flashing like lightning.Ibn Battuta (14th century travel writer)

The Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra), Jerusalem, 691–92 (Umayyad), stone masonry, wooden roof, decorated with glazed ceramic tile, mosaics, and gilt aluminum and bronze dome, with multiple renovations, patron the Caliph Abd al-Malik (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-NC 2.0)

A glorious mystery

One of the most iconic images of the Middle East is undoubtedly the Dome of the Rock shimmering in the setting sun of Jerusalem. Sitting atop the Haram al-Sharif, the highest point in old Jerusalem, the Dome of the Rock’s golden-color Dome and Turkish Faience tiles dominates the cityscape of Old Jerusalem and in the 7th century served as a testament to the power of the new faith of Islam. The Dome of the Rock is one of the earliest surviving buildings from the Islamic world. This remarkable building is not a mosque, as is commonly assumed, and scholars still debate its original function and meaning.

Between the death of the prophet Muhammad in 632 and 691/2, when the Dome of the Rock was completed, there was intermittent warfare in Arabia and Holy Land around Jerusalem. The first Arab armies who emerged from the Arabian peninsula were focused on conquering and establishing an empire—not building.

The Dome of the Rock was one of the first Islamic buildings ever constructed. It was built between 685 and 691/2 by Abd al-Malik, arguably the most important Umayyad caliph, as a religious focal point for his supporters, while he was fighting a civil war against Ibn Zubayr. When Abd al-Malik began construction on the Dome of the Rock, he did not have control of the Kaaba, the holiest shrine in Islam, which is located in Mecca.

The Dome is located on the Haram al-Sharif, an enormous open-air platform that now houses Al-Aqsa mosque, madrasas and several other religious buildings. Few places are as holy for Christians, Jews, and Muslims as the Haram al-Sharif. It is the Temple Mount, the site of the Jewish second temple, which the Roman Emperor Titus destroyed in 70 C.E. while subduing the Jewish revolt; a Roman temple was later built on the site. The Temple Mount was abandoned in Late Antiquity.

View of the Western Wall and the Dome of the Rock, Haram al-Sharif, the Temple Mount, Jerusalem (photo: Larry Koester, CC BY 2.0)

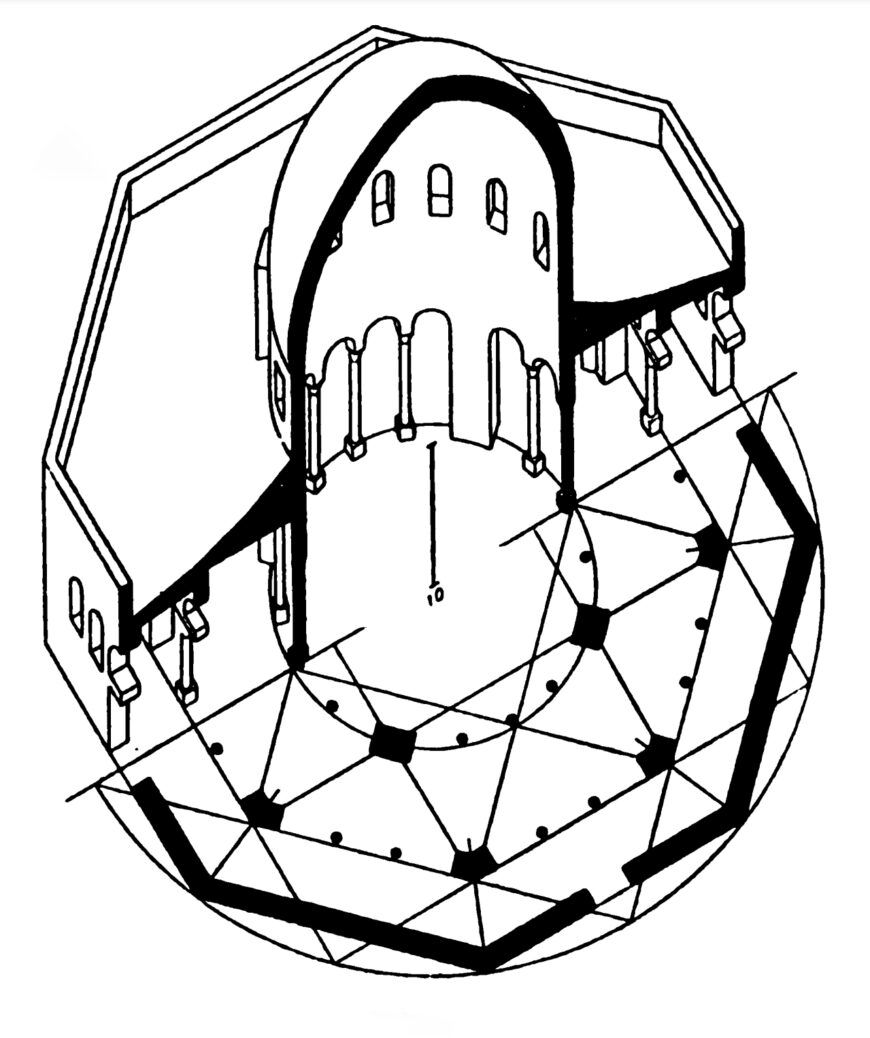

K.A.C. Creswell, Sectional axonometric view through dome (Creswell Archive, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

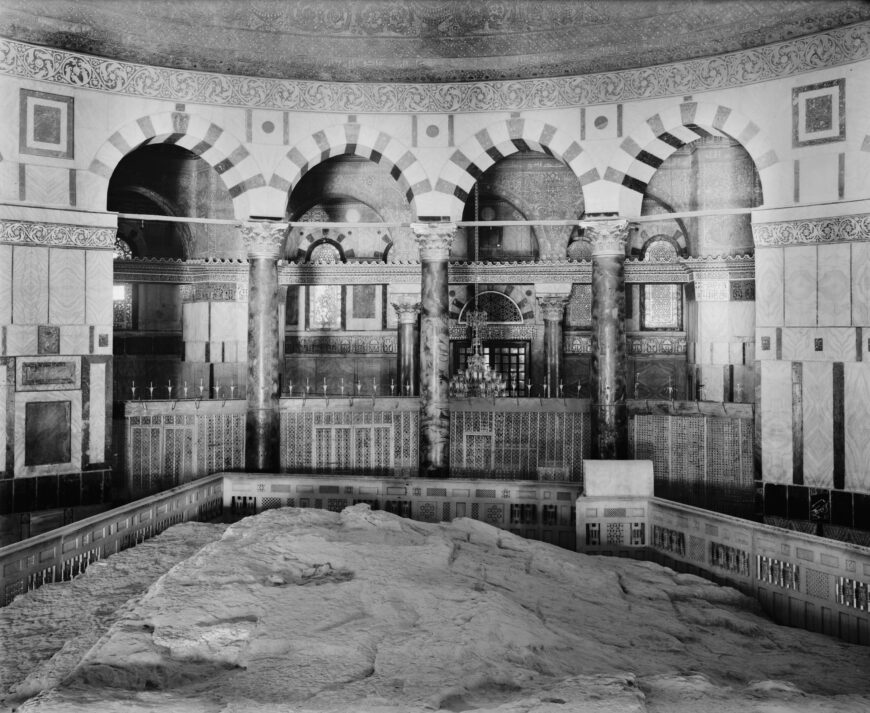

The rock in the Dome of the Rock

At the center of the Dome of the Rock sits a large rock, which is believed to be the location where Abraham was prepared to sacrifice his son Ismail (Isaac in the Judeo/Christian tradition). Today, Muslims believe that the Rock commemorates the night journey of Muhammad. One night the Angel Gabriel came to Muhammad while he slept near the Kaaba in Mecca and took him to al-Masjid al-Aqsa (the farthest mosque) in Jerusalem. From the Rock, Muhammad journeyed to heaven, where he met other prophets, such as Moses and Christ, witnessed paradise and hell and finally saw God enthroned and circumambulated by angels.

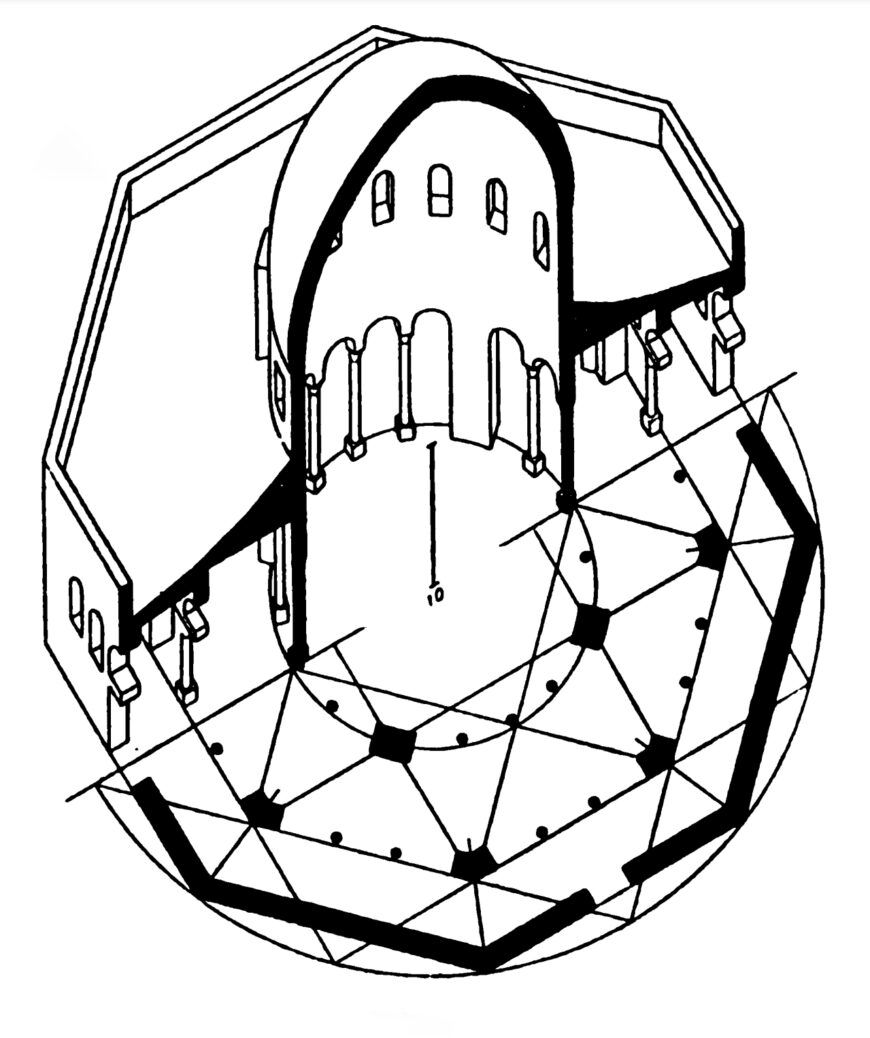

The Rock is enclosed by two ambulatories (in this case the aisles that circle the rock) and an octagonal exterior wall. The central colonnade (row of columns) was composed of four piers and twelve columns supporting a rounded drum that transitions into the two-layered dome more than 20 meters in diameter.

The colonnades are clad in marble on their lower registers, and their upper registers are adorned with exceptional mosaics. The ethereal interior atmosphere is a result of light that pours in from grilled windows located in the drum and exterior walls. Golden mosaics depicting jewels shimmer in this glittering light. Byzantine and Sasanian crowns in the midst of vegetal motifs are also visible.

The Byzantine Empire stood to the North and to the West of the new Islamic Empire until 1453, when its capital, Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Turks. To the East, the old Sasanian Empire of Persia imploded under pressure from the Arabs, but nevertheless provided winged crown motifs that can be found in the Dome of the Rock.

Mosaics

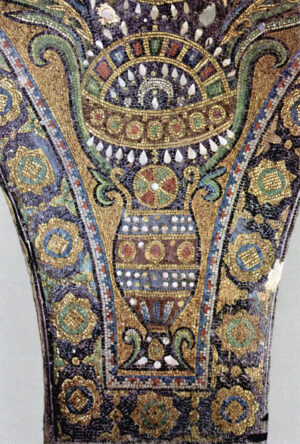

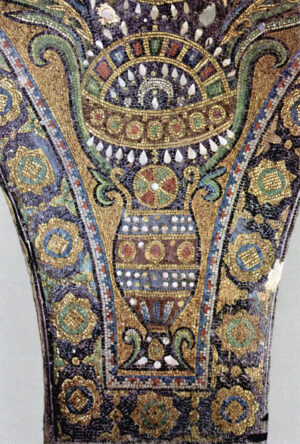

Mosaic detail from the Dome of the Rock

Wall and ceiling mosaics became very popular in Late Antiquity and adorn many Byzantine churches, including San Vitale in Ravenna and Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Thus, the use of mosaics reflects an artistic tie to the world of Late Antiquity. Late Antiquity is a period from about 300–800, when the Classical world dissolves and the Medieval period emerges.

The mosaics in the Dome of the Rock contain no human figures or animals. While Islam does not prohibit the use of figurative art per se, it seems that in religious buildings, this proscription was upheld. Instead, we see vegetative scrolls and motifs, as well as vessels and winged crowns, which were worn by Sasanian kings. Thus, the iconography of the Dome of the Rock also includes the other major pre-Islamic civilization of the region, the Sasanian Empire, which the Arab armies had defeated.

A reference to local churches

Scholars used to think that the building enclosing the Rock derived its form from the imperial mausolea (the burial places) of Roman emperors, such as Augustus or Hadrian. However, its octagonal form and Dome more likely referenced earlier local churches. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem was built to enclose the tomb of Christ. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher and the Dome of the Rock have domes that are almost identical in size; this suggests that the elevated position of the Dome of the Rock and the comparable size of its dome was a way that Muslims in the late 8th century proclaimed the superiority of their newly formed faith over Christians. Furthermore, the octagonal form of the Dome may derive from the Church of the Kathisma, a 5th-century church, later converted to a mosque, that was located between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. It was constructed over the rock where Mary reportedly sat on her way to Bethlehem. It is octagonal in shape and had an aisle that allowed circumambulation around the center. Therefore, rather than looking to the monuments of Rome, which was now far less important than Constantinople and Jerusalem, these local buildings may have been more important models.

Interior view of the Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra), Jerusalem, 691–92 (Umayyad), stone masonry, wooden roof, decorated with glazed ceramic tile, mosaics, and gilt aluminum and bronze dome, with multiple renovations, patron the Caliph Abd al-Malik (photo: Virtutepetens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Interior view of the Dome of the Rock with partial inscription (Qubbat al-Sakhra), Jerusalem, 691–692 (Umayyad) (photo: Virtutepetens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The inscription

The Dome of the Rock also contains an inscription, 240 meters long, that includes some of the earliest surviving examples of verses from the Qur‘an—in an architectural context or otherwise. The bismillah, the phrase that starts each verse of the Qu’ran, and the shahada, the Islamic confession of faith, which states that there is only one God and Muhammad is his prophet, are also included in the inscription. The inscription also refers to Mary and Christ and proclaims that Christ was not divine but a prophet. Thus the inscription also proclaims some of the core values of the newly formed religion of Islam. It also demonstrates the importance of calligraphy as a decorative form in Islamic Art.

Below the Rock is a small chamber, whose purpose is not fully understood even to this day. For those who are fortunate enough to be able to enter the Dome of the Rock, the experience is moving, regardless of one’s faith.

https://maps.google.com/maps?layer=c&panoid=F:-5J-6tmKsMDY/U4BoezrVdTI/AAAAAAAAFac/IwNaeOGGrUA&ie=UTF8&source=embed&output=svembed&cbp=13%2C360%2C%2C-0.29000000000000004%2C-15.1

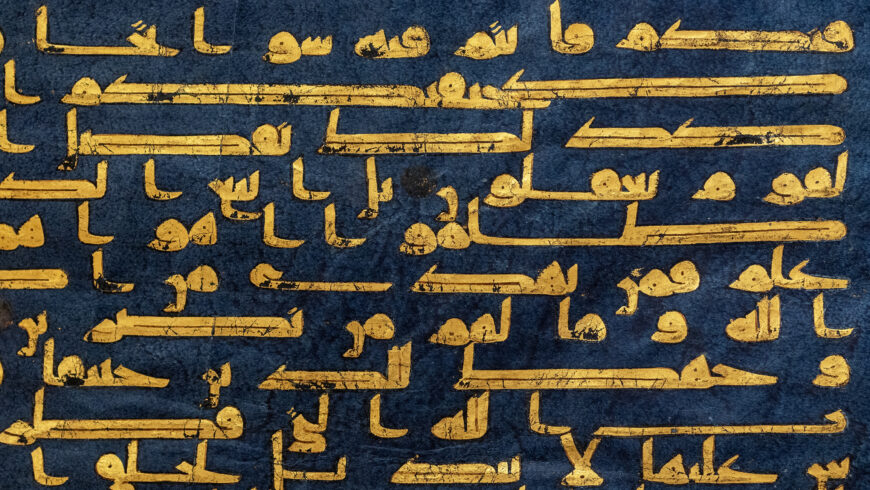

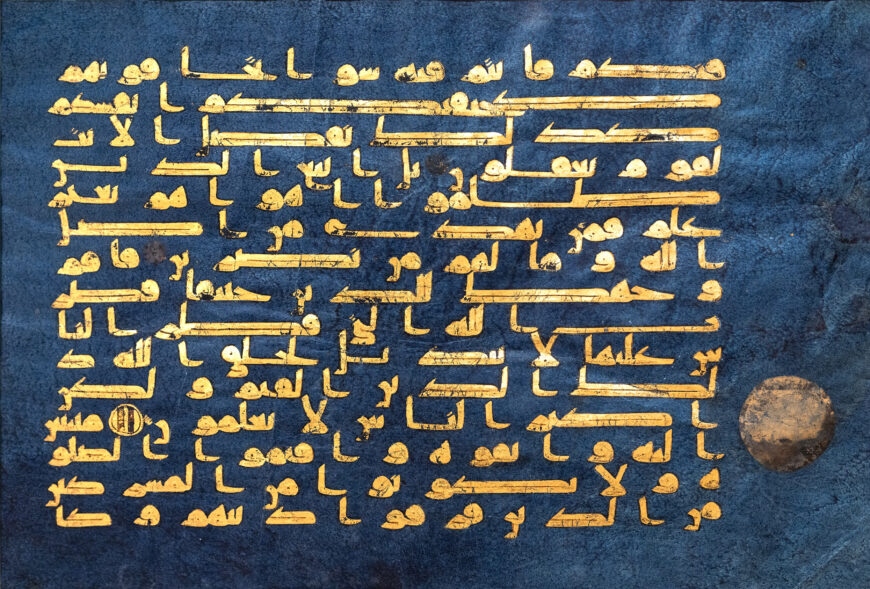

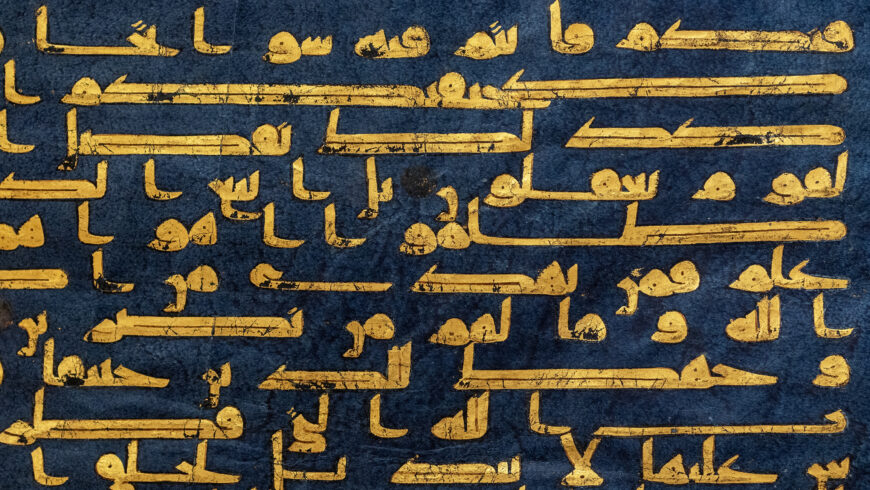

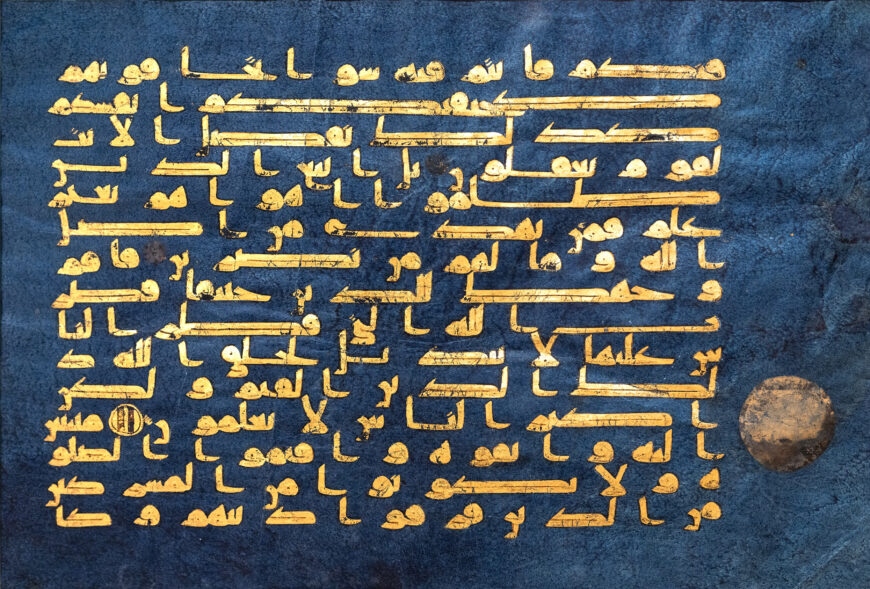

Upper right corner (detail), Folio from the “Blue Qur’an” with Sura 30 (al-Rum, “The Romans”), verses 25–32, late 9th–early 10th century C.E. (Tunisia) or 9th century (Spain), gold and silver on indigo-dyed parchment, 30.4 x 40.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Qur’an is the scripture of Islam, the words of God revealed to the Prophet Muhammad in the language of Arabic between the years 610 and 632 C.E. Having been memorized and passed orally during Muhammad’s lifetime, these revelations were written down for the first time soon after the prophet’s death, and as later centuries progressed, special scripts were devised and unique manuscript forms were developed to carry the words of God.

The earliest copies of the Qur’an do not survive as complete manuscripts but rather as individual folios or small groups of folios. This makes it difficult to reconstruct a history of this period of development: single pages do not necessarily convey much information about the larger manuscripts to which they belonged, and inscriptions at the end of manuscripts that might have given information about where and when they were produced have been lost. This essay therefore presents one narrative around these developments, and an introduction to how to approach the visual features of Qur’ans made between the 7th and 12th centuries C.E., when the scripts used to copy the Qur’an shifted from being plain and unadorned to what could properly be considered calligraphy (beautiful writing) and a major art form in Arabic-speaking regions.

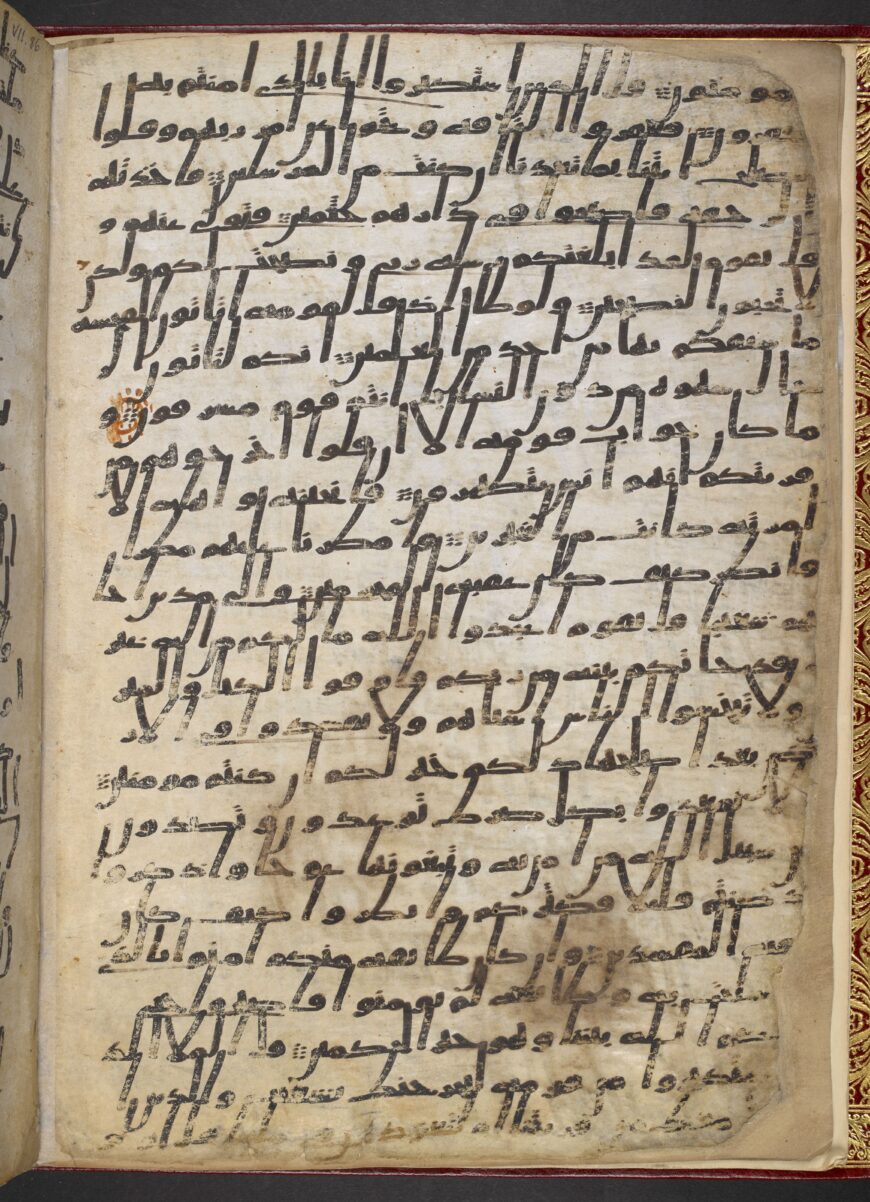

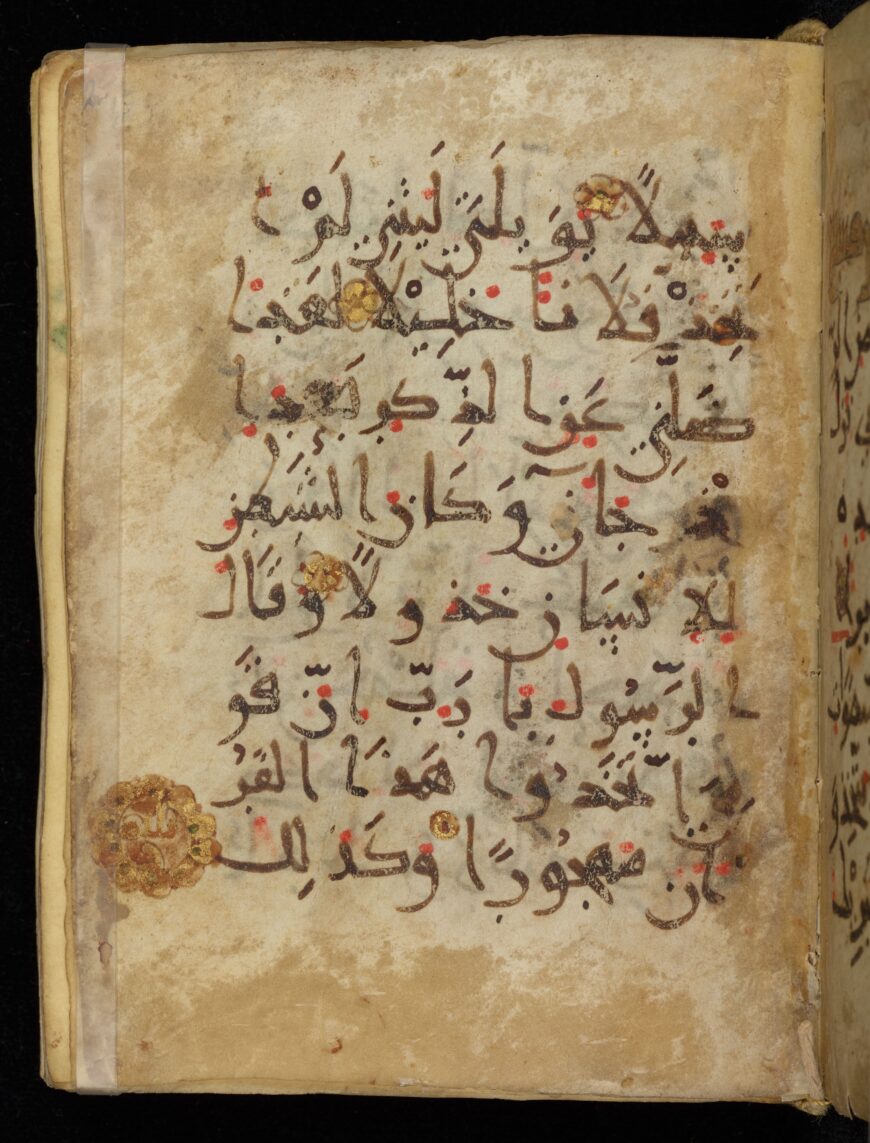

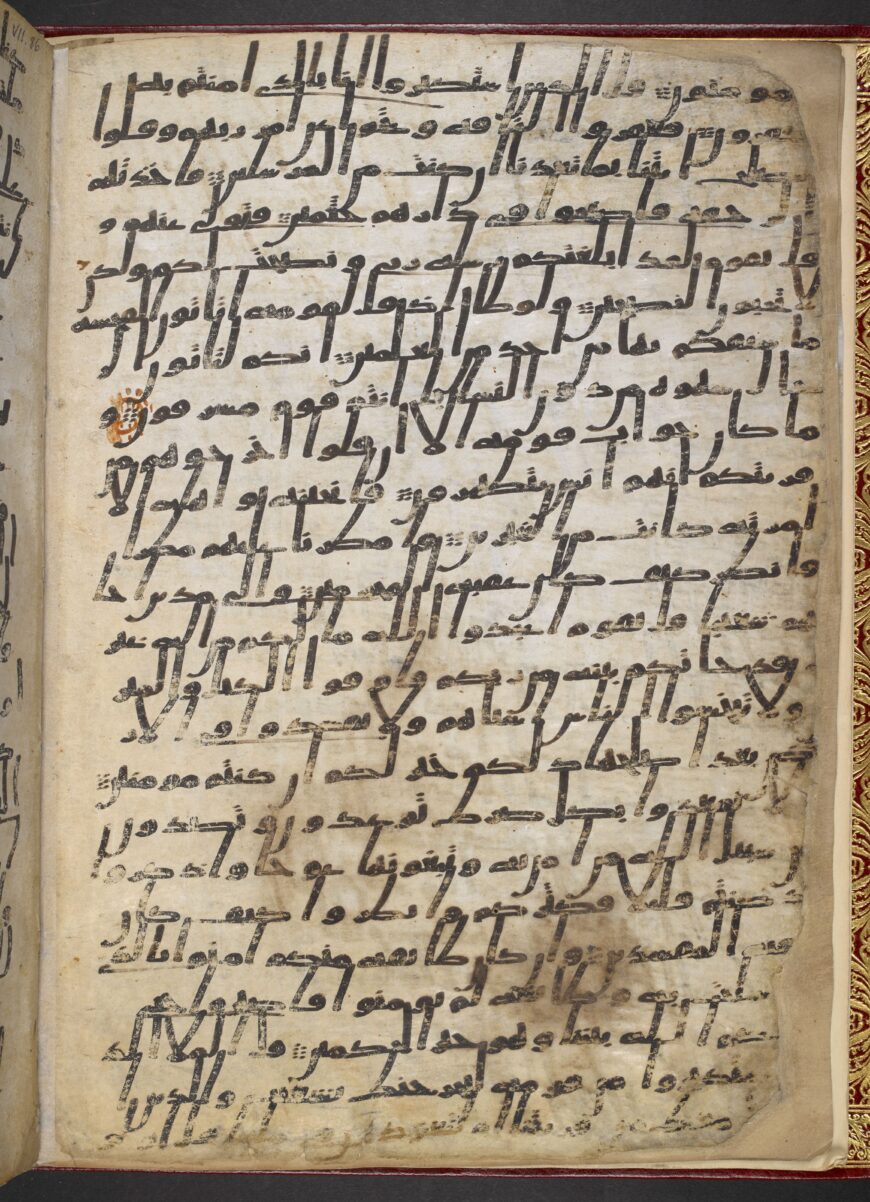

Qur’ans in hijazi scripts

Falling on the plainer end of the spectrum is one group of early Qur’ans, dating from the 7th and 8th centuries C.E., that is written in a family of scripts called hijazi. As seen on a page from an 8th century manuscript, the script is characterized by the accentuation of the vertical strokes of the letters. The letters slant to the right (to the beginning of each line, since Arabic is read from right to left). There are no dots that help distinguish letter forms from one another, and no dashes to mark the short vowels (in Arabic, short vowels do not have their own characters, and some consonants share character forms and are only distinguished with the addition of dots above or below these forms). It is also quite difficult to discern one word from another; spacing is uneven and words that come at the end of the line might be split and carried over to the next line, sometimes leaving just a single letter on its own.

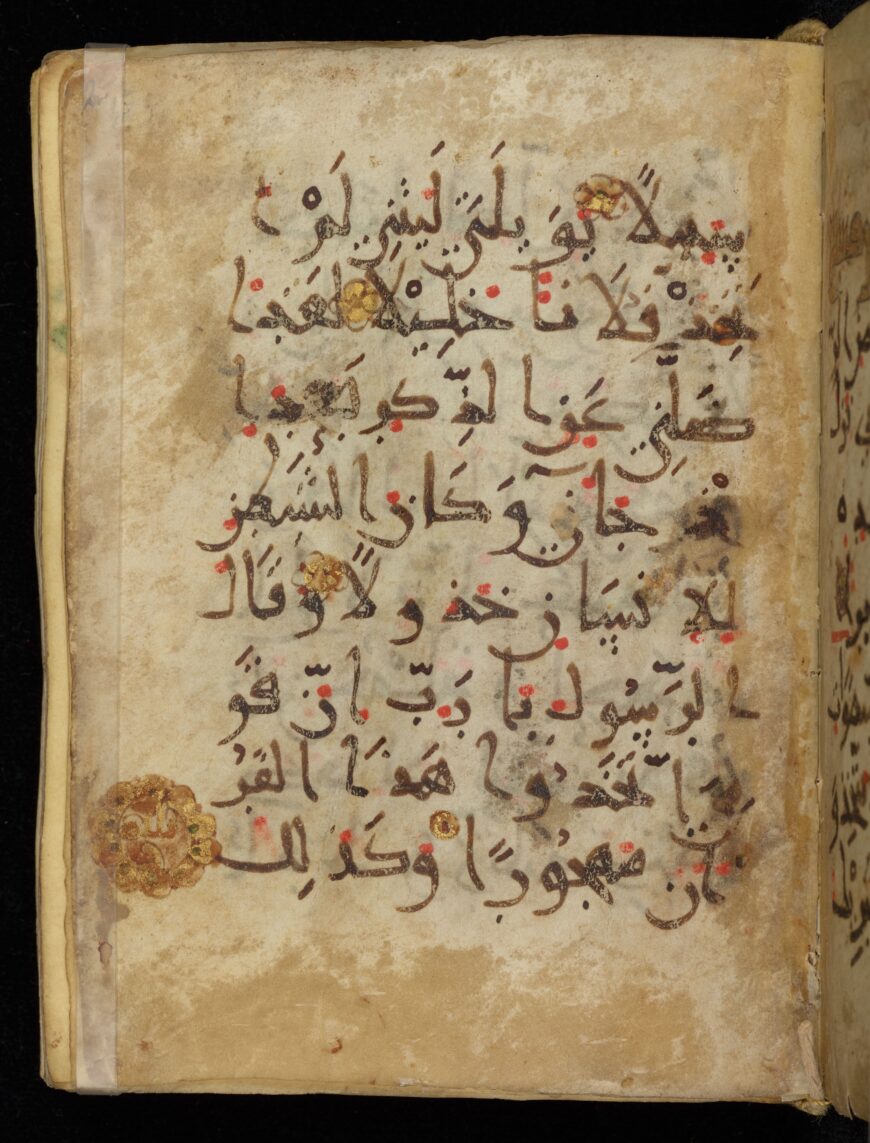

An example of hijazi script. Folio from a partial Qur’an manuscript, 8th century C.E. (Saudi Arabia), ink on parchment, 31.5 x 21.5 cm (British Library, London, Or. 2165, folio 2 verso)

This folio also exemplifies the physical and material attributes of typical hijazi Qur’ans. It is written in black ink on parchment (prepared animal skin). It is oriented vertically, with a height greater than the width. There are many lines of writing, in this case, 24. In these Qur’ans, the beginning of a new chapter might only be marked by a blank space or at most a small band of decoration in colored ink.

Because of the general difficulty in deciphering the text of manuscripts like this, scholars have postulated they were probably not used for a straight-forwarding reading, or by a reader who was not already familiar with the text; most think it was used to guide a reading or recitation by someone who had memorized the text already but might need a reminder along the way. Another supposition is that the Qur’an manuscript itself had a sanctity, and copies were kept in places like mosques, religious schools, tombs, or the home because of its sacred aura.

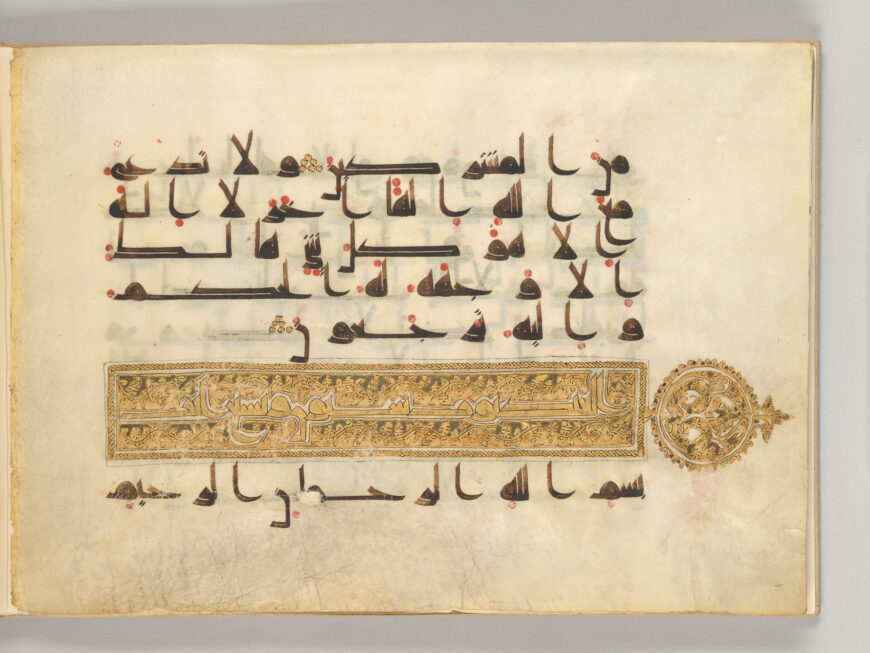

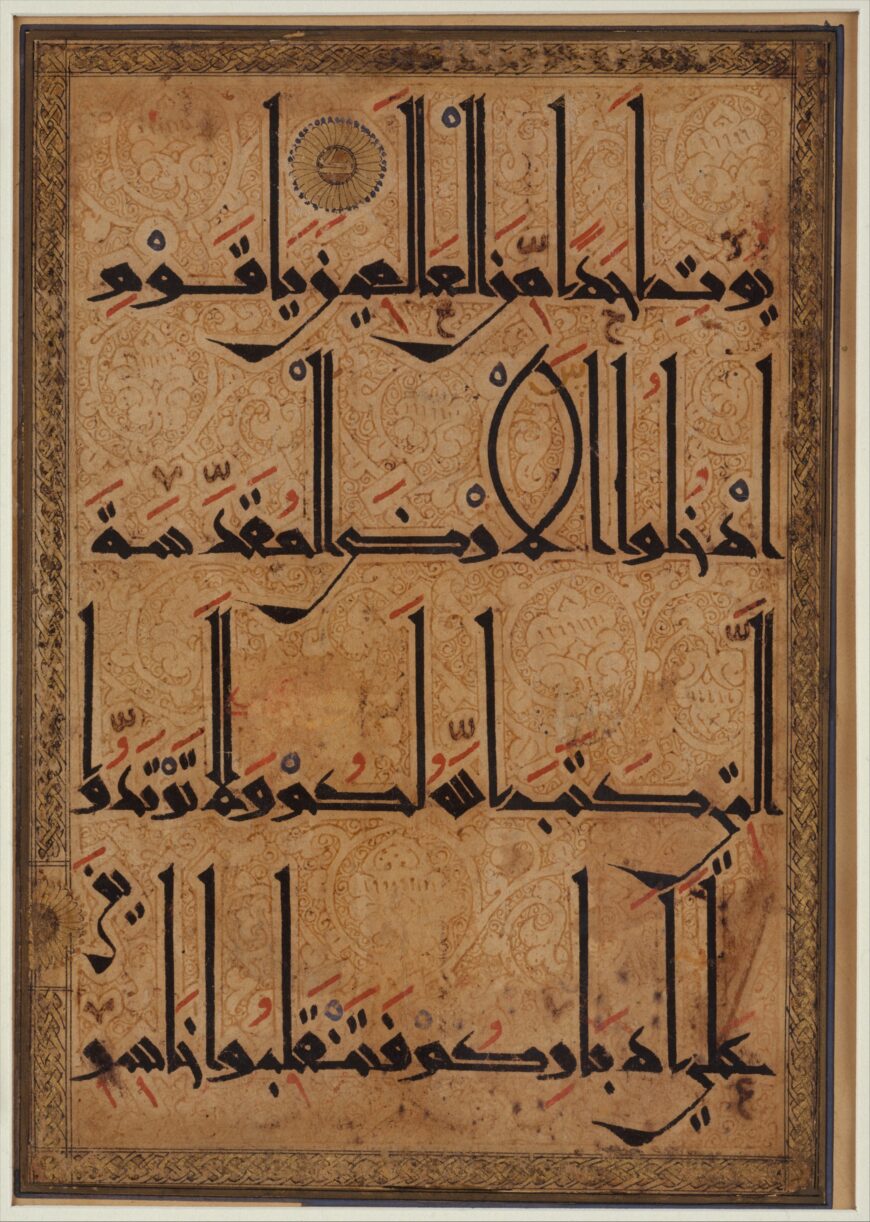

Qur’ans in kufic scripts

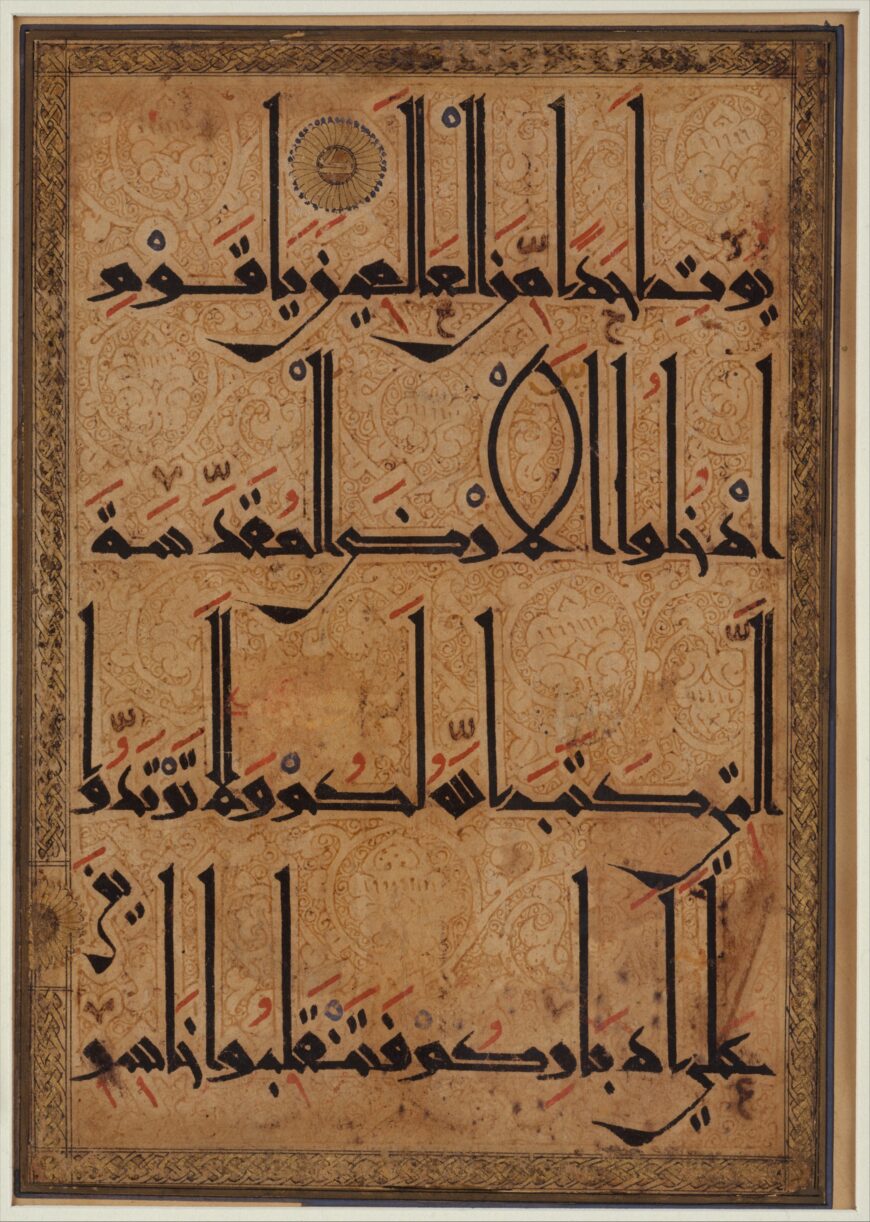

During this period, but perhaps in other regions, another script family was also in use. The kufic set of scripts is distinguished by the angularity of its letter forms, and the use of thicker strokes than in the hijazi scripts. As seen in this example, attributed variously to Spain in the 9th century or Tunisia in the mid-9th to mid-10th century, another major difference from hijazi scripts is the horizontal orientation of the script and the way that letters are often stretched across the page so that the words precisely fill the space for each line. The vertical strokes of letters are frequently shortened or bent over to the left.

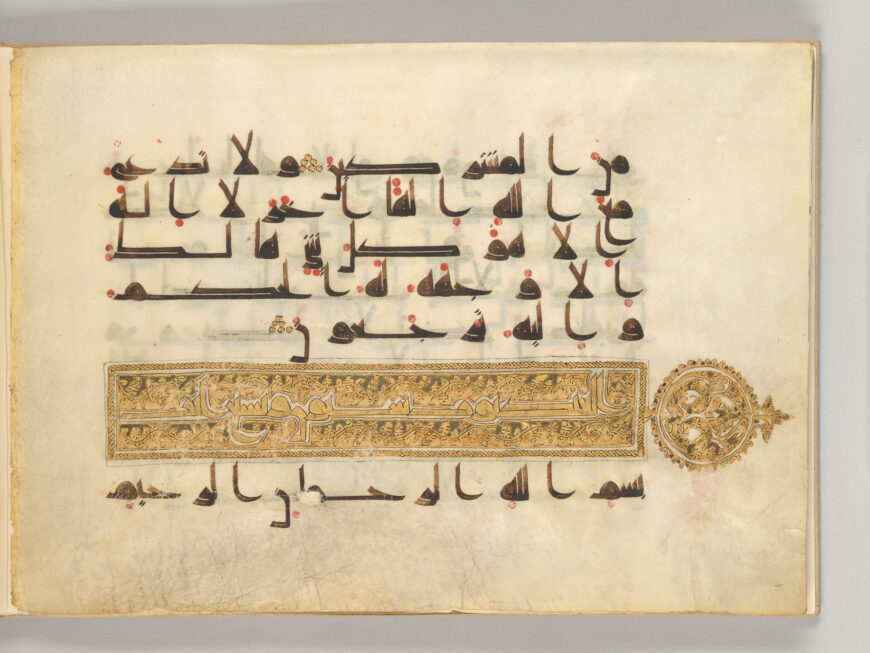

An example of kufic script. Folio from a partial Qur’an manuscript, before 911 C.E. (possibly Iraq), ink on vellum, folio 19 verso, 23 x 32 cm (The Morgan Library and Museum, New York, MS M.712)

Unlike Qur’ans in hijazi script, kufic Qur’ans tend to make use of diacritics (the marks that help distinguish letters written with the same form), as well as dots that indicate different short vowels. In some manuscripts, these dots (called vocalizations), are given in different colors that indicate variant readings of the Qur’an. On this page of a 10th century C.E. Qur’an from Iraq, the dots have been included in a red ink. The inclusion of these marks helps avoid confusion about which letter has been written, and also assists someone reciting the Qur’an aloud to pronounce the words correctly.

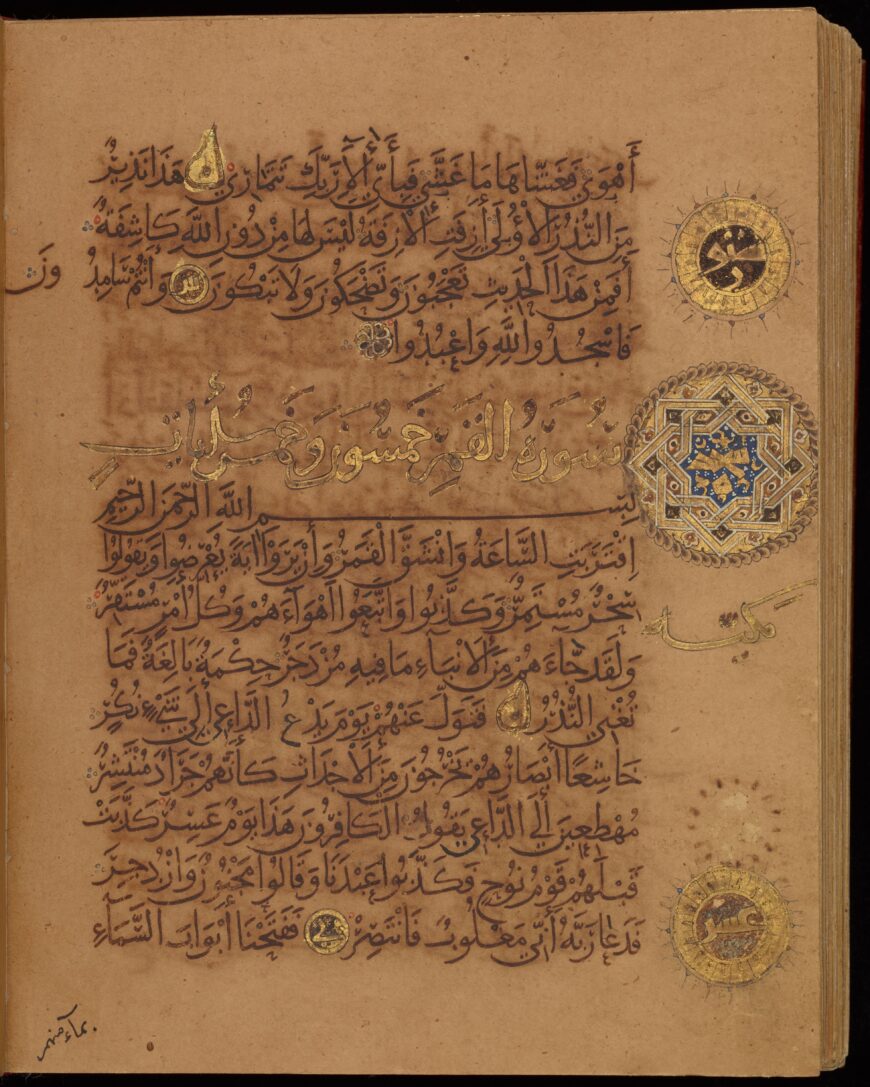

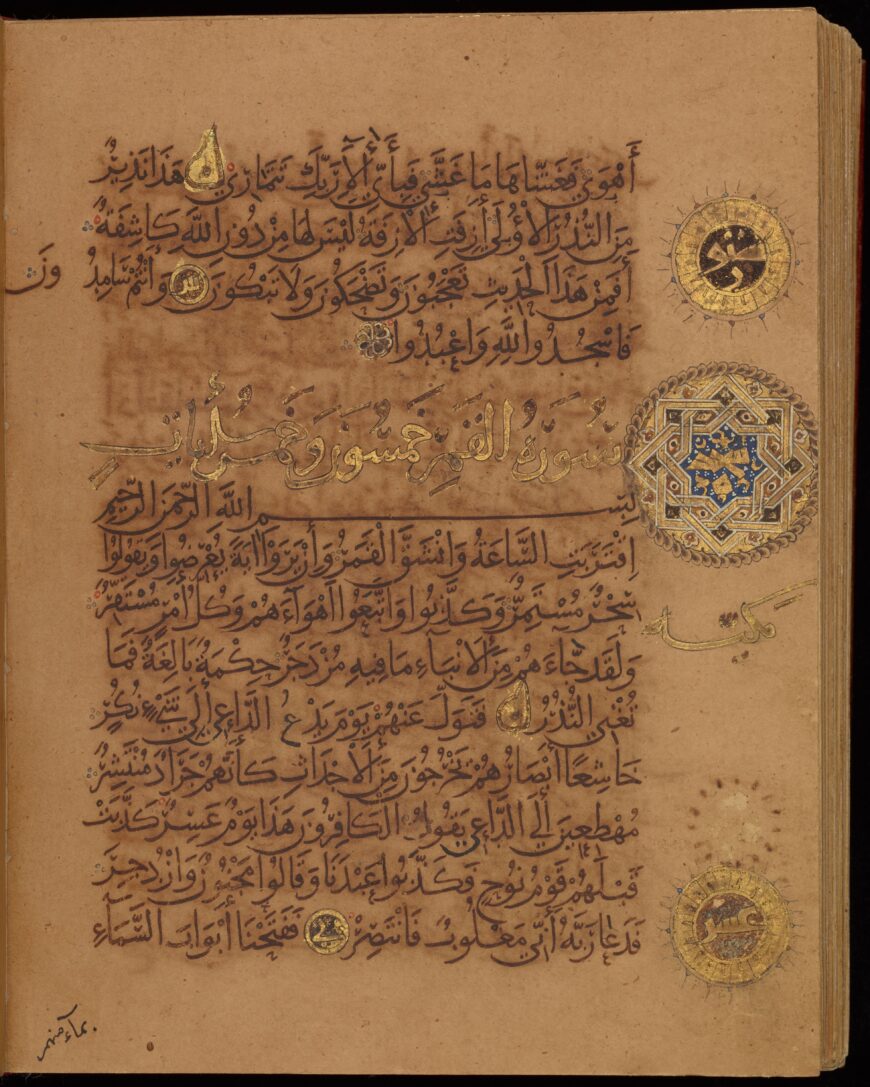

Another point of difference is that in kufic Qur’ans, decorated bands that mark the beginnings of chapters appear more consistently, and include the numbers of verses in the chapter along with the chapter name. The Qur’an shown here presents a useful example. Its golden illumination includes the words, ‘al-ankabut, nine and sixty ayat ,’ indicating that this is sura al-ankabut (the spider), with 69 verses.

An example of kufic script. Folio from the “Blue Qur’an” with Sura 30 (al-Rum, “The Romans”), verses 25–32, late 9th–early 10th century C.E. (Tunisia) or 9th century (Spain), gold and silver on indigo-dyed parchment, 30.4 x 40.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In terms of format, Qur’ans in kufic scripts tend to have folios that are oriented horizontally. Most have a limited number of lines per page, sometimes as few as three or five. This means that enormous amounts of parchment would have been required to create each Qur’an, and they would therefore have been expensive to produce. By way of example, the page from the “Blue Qur’an” has fifteen lines of writing on it; from this basis, it has been estimated that it would have originally had 650 parchment folios requiring the hides of many animals. The folios were additionally dyed with indigo and inscribed with gold ink, making it an even more costly production.

Qur’ans in rounded scripts

The hijazi and kufic styles, often described as rectilinear or angular, continued to appear into the 11th century by which time a group of what are called “round scripts” increased in use. These scripts had already been employed for many kinds of other texts, but had not apparently been considered appropriate for the Qur’an (a deliberate distinction had previously been made between the scripts used to write out the words of God and those used for other purposes). The reasons for the rise and eventual acceptance of round scripts for use in copying Qur’ans are not universally agreed on by scholars, but may have to do with changes in the type of people who wrote out the Qur’an, which over time shifted from clerics to those employed as secretaries or scribes in the government infrastructure. These scribes were more accustomed to using round, or cursive, scripts that were faster and easier to write, and which, unlike the hijazi and kufic styles, did not require lifting the pen repeatedly to form individual letters. The new scripts were much simpler to read which would have also added to their general popularity.

Bifolium from a Qur’an manuscript in round script, with last word of Sura 26 (al-Shu‘ara, “The Poets”), verse 227 and Sura 27 (al-Naml, “The Ant”), verses 1–7, late 9th–early 10th century C.E. (Iran; a note in Persian says it was corrected in 905 C.E.), ink on parchment, 12 x 9 cm, folios 33b–34a (Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Is 1417d)

The transition to cursive scripts was gradual, however, and many styles flourished in 9th–12th centuries as variations developed in different geographic regions, some retaining more aspects of the angular scripts (like hijazi and kufic) than others. In Iran, for instance, a very early attempt at a rounded script hints at the attributes that were appealing in the new style. In this late 9th–early 10th century manuscript, there is greater uniformity in the width and length of the letters compared to the kufic and hijazi scripts, and the letter forms are distinct and legible, not having been stretched or flattened. The rounded extensions of letters that descend below the line of writing visually link one word to the next and help guide the eye across the page. Yet at the same time there is significant variation in the thickness of the strokes composing the letters, and the spacing between words is uneven, creating a certain visual busy-ness.

These matters would be resolved as various guidelines for writing cursive scripts were introduced. These advancements have traditionally been associated with three calligraphers, the first of whom, Ibn Muqla is said to have created a system of proportions between the letters based on a basic unit of the diamond shape made when the scribe’s reed pen is applied to the writing surface. The height and width of each letter in the script was then a given number of these units.

Qur’an of Ibn al-Bawwab with Sura 53 (al-Najm, “The Star”), verse 53 and Sura 54 (al-Qamar, “The Moon”), verses 1–11, dated 391 A.H./1000–1001 C.E. (Baghdad, Iraq), ink and gold pigment on paper, 18.3 x 14.5 cm, folio 243b (Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Is 1431)

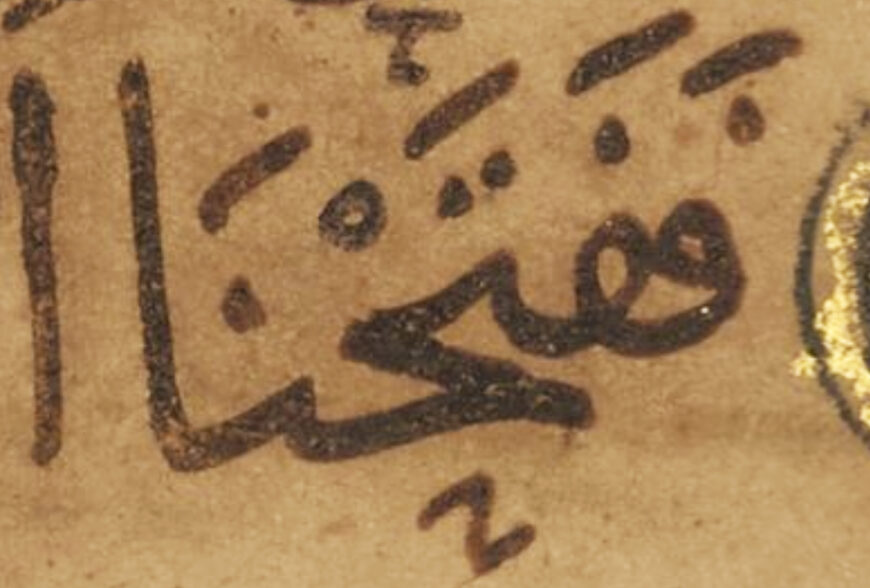

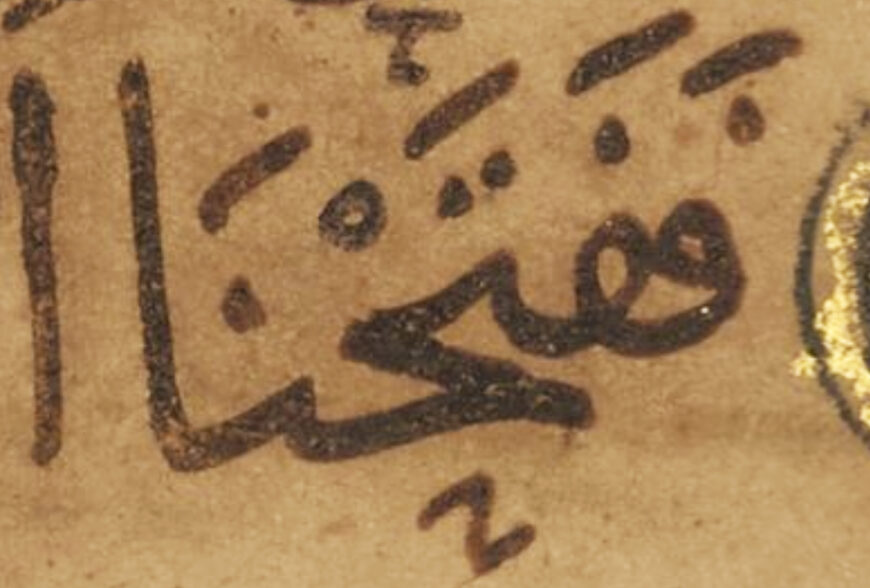

The next major advancement is attributed to Ibn al-Bawwab, who perfected a graceful, flowing, and highly readable style of writing based on this idea of proportions. This can be best seen in a Qur’an signed by him and dated to the year 1000–1001. The letters on its pages are of an even thickness and are arranged in a steady rhythm across each line, united by the rounded strokes of the letters that extend into the spaces between words. The text includes a complete set of diacritics and vocalization marks, given in the same color ink as the text, which further aids in its legibility.

Vocalization marks (note the dashes above the word) from the bottom line of the page (detail), Qur’an of Ibn al-Bawwab with Sura 53 (al-Najm, “The Star”), verse 53 and Sura 54 (al-Qamar, “The Moon”), verses 1–11, dated 391 A.H./1000–1001 C.E. (Baghdad, Iraq), ink and gold pigment on paper, 18.3 x 14.5 cm, folio 243b (Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Is 1431)

It is believed these innovations were introduced because by this time the Muslim population had multiplied, and many Muslims were not native Arabic speakers so these additions made it easier for those learning the Qur’an to read and understand its language. They also help to distinguish the different readings of the Qur’an, some of which were established during these centuries. Though there is only one version of the text of the Qur’an, there are different traditions about where certain verses end, how certain words are pronounced, the intonation to use when reading the words aloud, and other such details.

These changes to the script coincided with changes to the way that Qur’an manuscripts were made. This one was copied on pages made of paper, and vertically-oriented paper pages would become the norm for most Qur’ans after this time because they were much easier and cheaper to produce than those made of parchment. [1]

Continued variation

Although Ibn al-Bawwab’s Qur’an is considered a landmark in the study of art history, and rounded scripts would eventually gain nearly universal popularity, there was still considerable variety in the Qur’ans being produced through the 12th century. These variations could reflect the region where a particular Qur’an was made, or factors such as the cost of the manuscript and its intended use (with simpler versions for daily prayer contrasting with those presented as endowments to important mosques).

Bifolium from the “Nurse’s Qur’an” with Sura 6 (al-An‘am, “The Cattle”), verses 40–41, 48–49, c. 1019–20 (Tunisia), ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on parchment, 44.5 x 60 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

For example, the “Nurse’s Qur’an” presents a different, rather angular script. This manuscript was likely made in Tunisia, a commission by the nursemaid to a sultan of the Zirid dynasty, and is an example of a lavish production, made as a gift to the Great Mosque of Qairawan. Its large parchment folios each have five lines of writing in brown ink, along with short vowels written in red, blue, and green colored inks. Its distinctive style of calligraphy is characterized by thickly-formed letters with contrasting thin strokes for parts of certain letter forms. The letters are distributed evenly across each line with minimal spacing between words, giving the pages a powerful graphic impact, but making it quite hard to read the letters until one becomes accustomed to the script’s internal logic.

Folio from a Qur’an manuscript with Sura 5 (al-Ma’idah, “The Feast”), verses 20–21, c. 1180 (Iran or Afghanistan), ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 29.8 x 22.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

A Qur’an made later, in the 12th century in Iran or Afghanistan, similarly presents a highly stylized script. The vertical strokes of some letters are accentuated, while others bend and stretch horizontally. Most notably, the rounded edges of the letter forms have been squared off, in contrast again to Ibn al-Bawwab’s writing. Knowing that these forms would be difficult to distinguish, the calligrapher has written an easier-to-decipher version of some letters in a lighter ink just below the lines of writing (as seen near the right-hand side of the first line).

Conclusion

In the first centuries of the religion of Islam, the many developments in writing Arabic that took place were initially propelled by the desire to copy the Qur’an in a suitably reverential manner. Later there arose the need to provide a clear and legible version of the text that might be easily read in many different parts of the world. These orthographic changes took place in parallel with changes to the scripts being developed for use in the governmental structure, as Arabic started being used as the language of administration in a wider geographic span than ever before. Together these influences led to a significant transformation in the appearance and functionality of the Qur’an. After this time, even more variations in scripts and illuminations would be developed, as many regional traditions gained in prominence.

Notes:

[1] Some two hundred years later, a calligrapher named Yaqut al-Musta’simi would then establish six different proportional scripts based on Ibn Muqla’s system. Each script used a different sized pen, that created different sizes and thicknesses for its letters.

Additional resources

The Qur’an of Ibn al-Bawwab online

Sheila Blair, Islamic Calligraphy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006).

François Déroche, “Written Transmission,” The Wiley Blackwell Companion to the Qur’an, Second Edition (Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 2017), pp. 184–99.

Cite this page as: Dr. Marika Sardar, “The Qur’an and the development of Arabic scripts between the 7th and 12th centuries,” in Smarthistory, July 27, 2023, accessed July 29, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/quran-arabic-scripts/.