The earliest writing we know of dates back to around 3000 B.C.E. and was probably invented by the Sumerians, living in major cities with centralized economies in what is now southern Iraq. The earliest tablets with written inscriptions represent the work of administrators, perhaps of large temple institutions, recording the allocation of rations or the movement and storage of goods. Temple officials needed to keep records of the grain, sheep, and cattle entering or leaving their stores and farms and it became impossible to rely on memory. So, an alternative method was required and the very earliest texts were pictures of the items scribes needed to record (known as pictographs).

Early writing tablet recording the allocation of beer, 3100–3000 B.C.E, Late Prehistoric period, clay, probably from southern Iraq. (© Trustees of the British Museum) The symbol for beer, an upright jar with pointed base, appears three times on the tablet. Beer was the most popular drink in Mesopotamia and was issued as rations to workers. Alongside the pictographs are five different shaped impressions, representing numerical symbols. Over time these signs became more abstract and wedge-like, or “cuneiform.” The signs are grouped into boxes and, at this early date, are usually read from top to bottom and right to left. One sign, in the bottom row on the left, shows a bowl tipped towards a schematic human head. This is the sign for “to eat.”

Writing, the recording of a spoken language, emerged from earlier recording systems at the end of the fourth millennium. The first written language in Mesopotamia is called Sumerian. Most of the early tablets come from the site of Uruk, in southern Mesopotamia, and it may have been here that this form of writing was invented.

These texts were drawn on damp clay tablets using a pointed tool. It seems the scribes realized it was quicker and easier to produce representations of such things as animals, rather than naturalistic impressions of them. They began to draw marks in the clay to make up signs, which were standardized so they could be recognized by many people.

Cuneiform

From these beginnings, cuneiform signs were put together and developed to represent sounds, so they could be used to record spoken language. Once this was achieved, ideas and concepts could be expressed and communicated in writing.

Cuneiform is one of the oldest forms of writing known. It means “wedge-shaped,” because people wrote it using a reed stylus cut to make a wedge-shaped mark on a clay tablet. Letters enclosed in clay envelopes, as well as works of literature, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh have been found. Historical accounts have also come to light, as have huge libraries such as that belonging to the Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal. Cuneiform writing was used to record a variety of information such as temple activities, business, and trade. Cuneiform was also used to write stories, myths, and personal letters. The latest known example of cuneiform is an astronomical text from 75 C.E. During its 3,000-year history, cuneiform was used to write around 15 different languages including Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Elamite, Hittite, Urartian, and Old Persian.

Cuneiform tablets at the British Museum

The department’s collection of cuneiform tablets is among the most important in the world. It contains approximately 130,000 texts and fragments and is perhaps the largest collection outside of Iraq. The centerpiece of the collection is the Library of Ashurbanipal, comprising many thousands of the most important tablets ever found. The significance of these tablets was immediately realized by the Library’s excavator, Austin Henry Layard, who wrote:

They furnish us with materials for the complete decipherment of the cuneiform character, for restoring the language and history of Assyria, and for inquiring into the customs, sciences, and . . . literature, of its people.

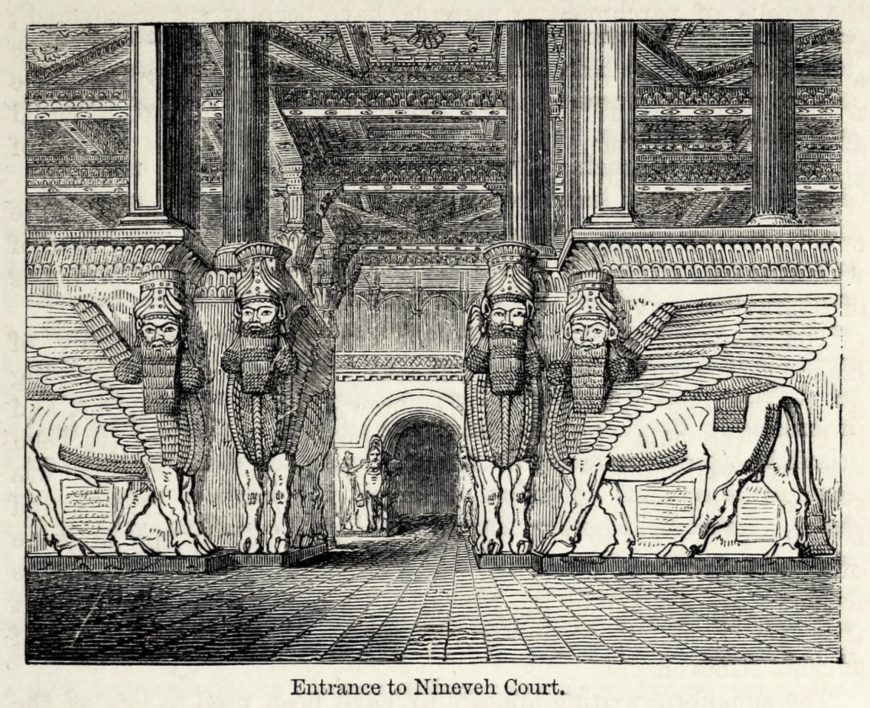

The Library of Ashurbanipal is the oldest surviving royal library in the world. British Museum archaeologists discovered more than 30,000 cuneiform tablets and fragments at his capital, Nineveh (modern Kuyunjik). Alongside historical inscriptions, letters, and administrative and legal texts, were found thousands of divinatory, magical, medical, literary and lexical texts. This treasure-house of learning has held unparalleled importance to the modern study of the ancient Near East ever since the first fragments were excavated in the 1850s.

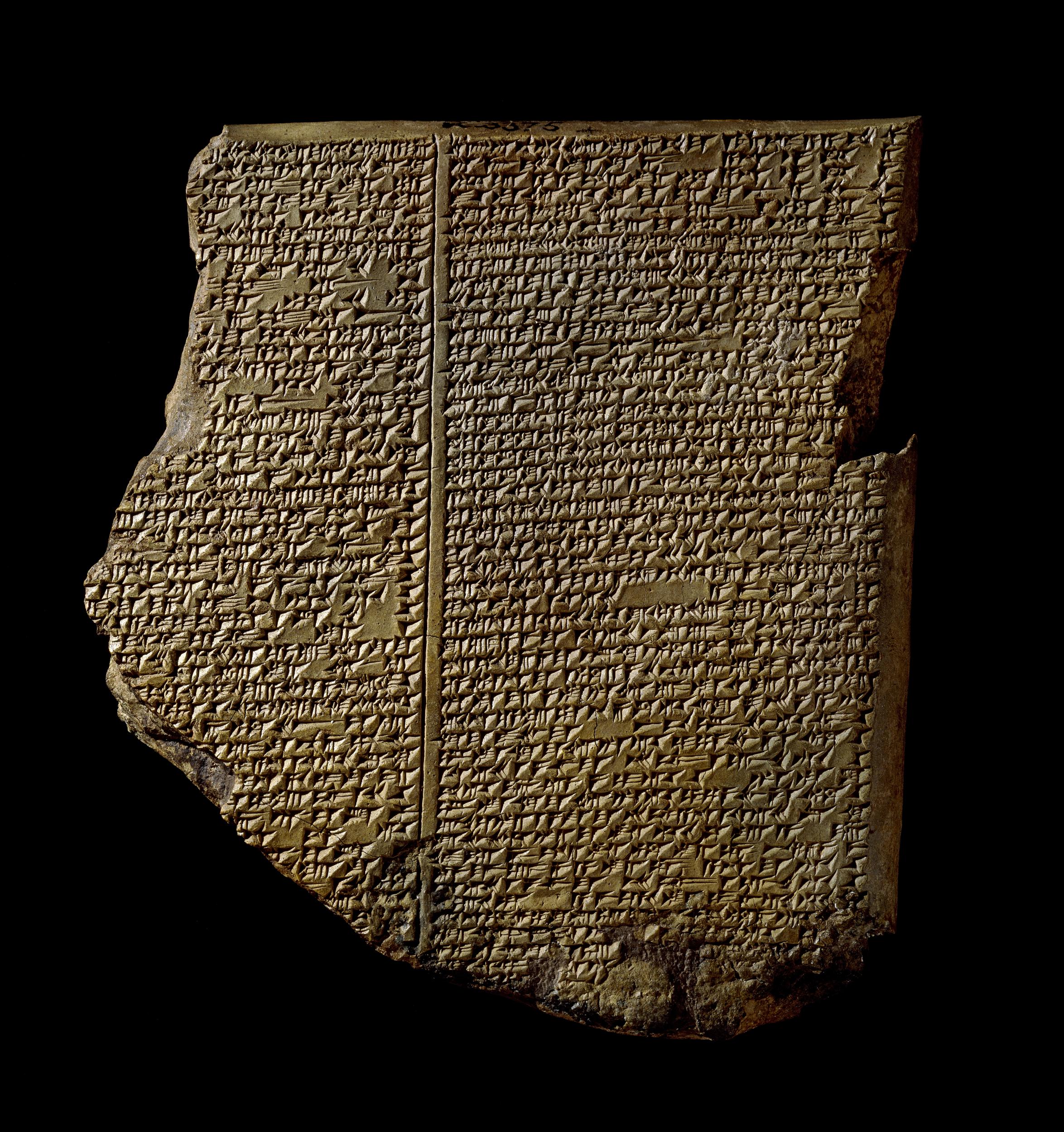

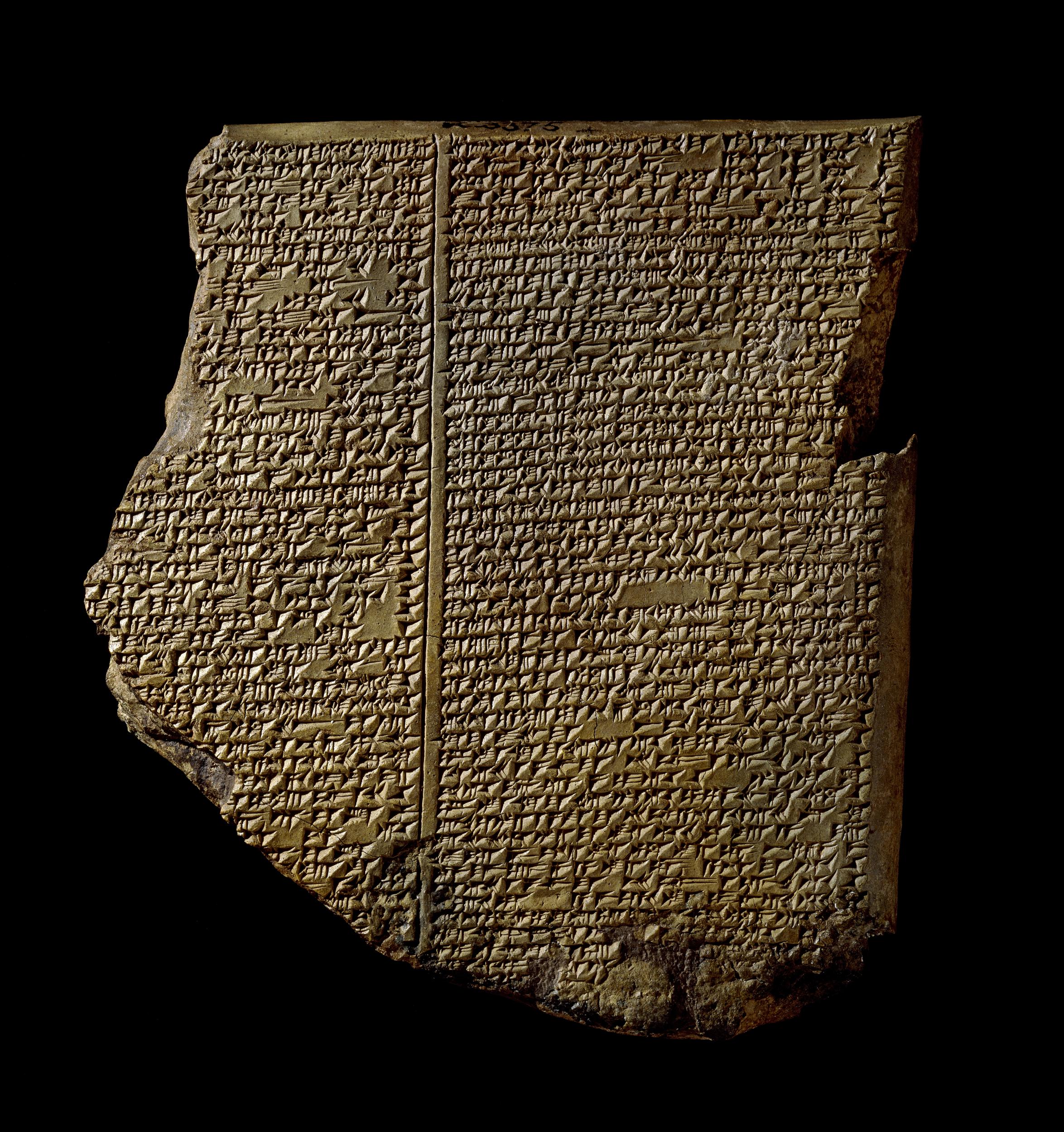

The Flood Tablet, part of the “Epic of Gilgamesh,” 7th century B.C.E., Neo-Assyrian, 15.24 x 13.33 x 3.17 cm, from Nineveh, northern Iraq (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Epic of Gilgamesh and The Flood Tablet

The best known piece of literature from ancient Mesopotamia is the story of Gilgamesh, a legendary ruler of Uruk, and his search for immortality. The Epic of Gilgamesh is a huge work, the longest piece of literature in Akkadian (the language of Babylonia and Assyria). It was known across the ancient Near East, with versions also found at Hattusas (capital of the Hittites), Emar in Syria, and Megiddo in the Levant.

This, the eleventh tablet of the Epic, describes the meeting of Gilgamesh with Utnapishtim. Like Noah in the Hebrew Bible, Utnapishtim had been forewarned of a plan by the gods to send a great flood. He built a boat and loaded it with all his precious possessions, his kith and kin, domesticated and wild animals and skilled craftsmen of every kind.

Utnapishtim survived the flood for six days while mankind was destroyed, before landing on a mountain called Nimush. He released a dove and a swallow but they did not find dry land to rest on, and returned. Finally a raven that he released did not return, showing that the waters must have receded.

This Assyrian version of the Old Testament flood story is the most famous cuneiform tablet from Mesopotamia. It was identified in 1872 by George Smith, an assistant in The British Museum. On reading the text “he … jumped up and rushed about the room in a great state of excitement, and, to the astonishment of those present, began to undress himself.”

This tablet contains both a cuneiform inscription and a unique map of the Mesopotamian world. Babylon is shown in the centre (the rectangle in the top half of the circle), and Assyria, Elam, and other places are also named. Map of the World, Late Babylonian, c. 500 B.C.E., clay, findspot: Abu Habba, 12.2 x 8.2 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Map of the world

This tablet contains both a cuneiform inscription and a unique map of the Mesopotamian world. Babylon is shown in the center (the rectangle in the top half of the circle), and Assyria, Elam, and other places are also named.

The central area is ringed by a circular waterway labelled “Salt-Sea.” The outer rim of the sea is surrounded by what were probably originally eight regions, each indicated by a triangle, labelled “Region” or “Island,” and marked with the distance in between. The cuneiform text describes these regions, and it seems that strange and mythical beasts as well as great heroes lived there, although the text is far from complete. The regions are shown as triangles since that was how it was visualized that they first would look when approached by water.

The map is sometimes taken as a serious example of ancient geography, but although the places are shown in their approximately correct positions, the real purpose of the map is to explain the Babylonian view of the mythological world.

Observations of Venus

Thanks to Assyrian records, the chronology of Mesopotamia is relatively clear back to around 1200 B.C.E. However, before this time dating is less certain.

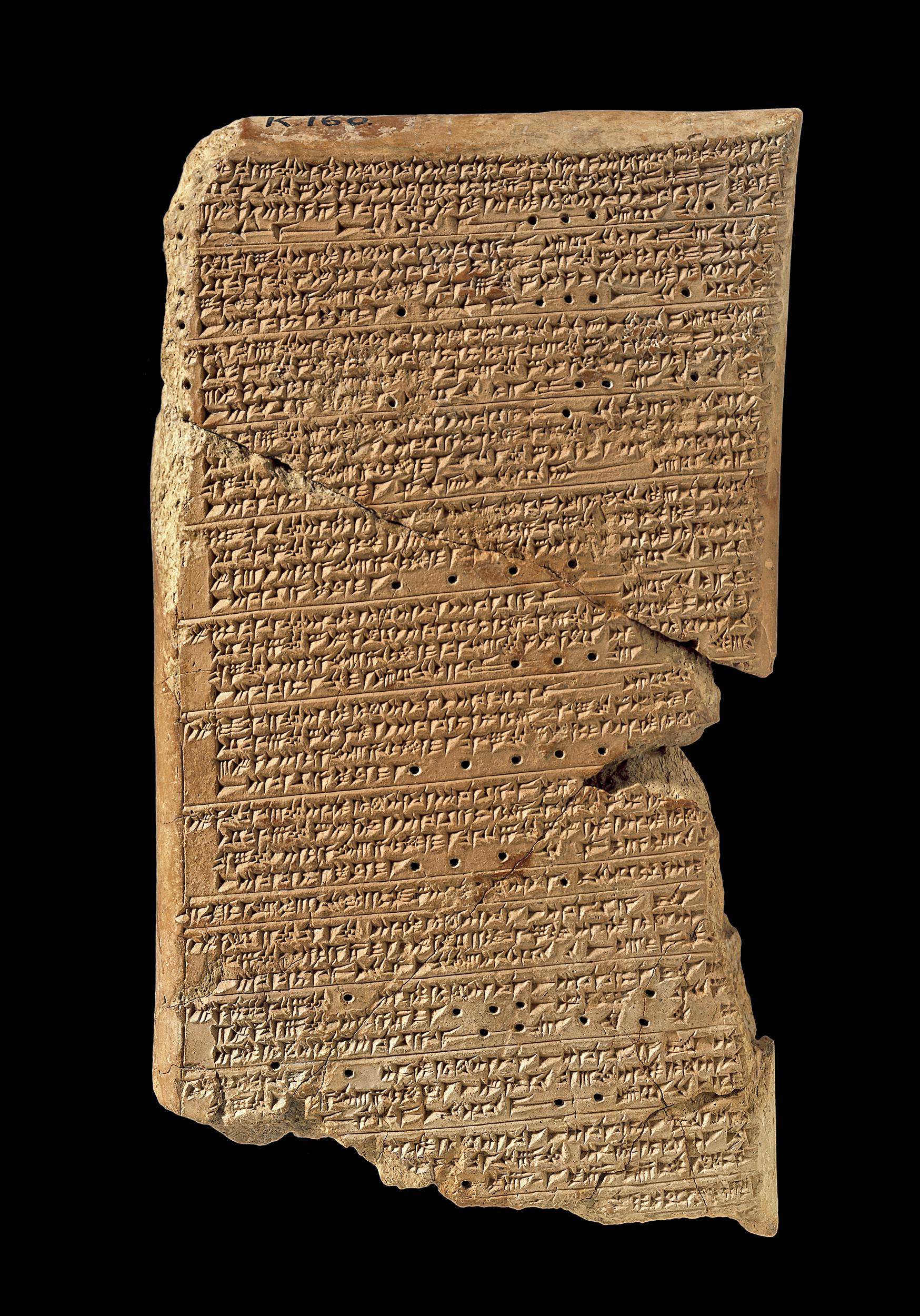

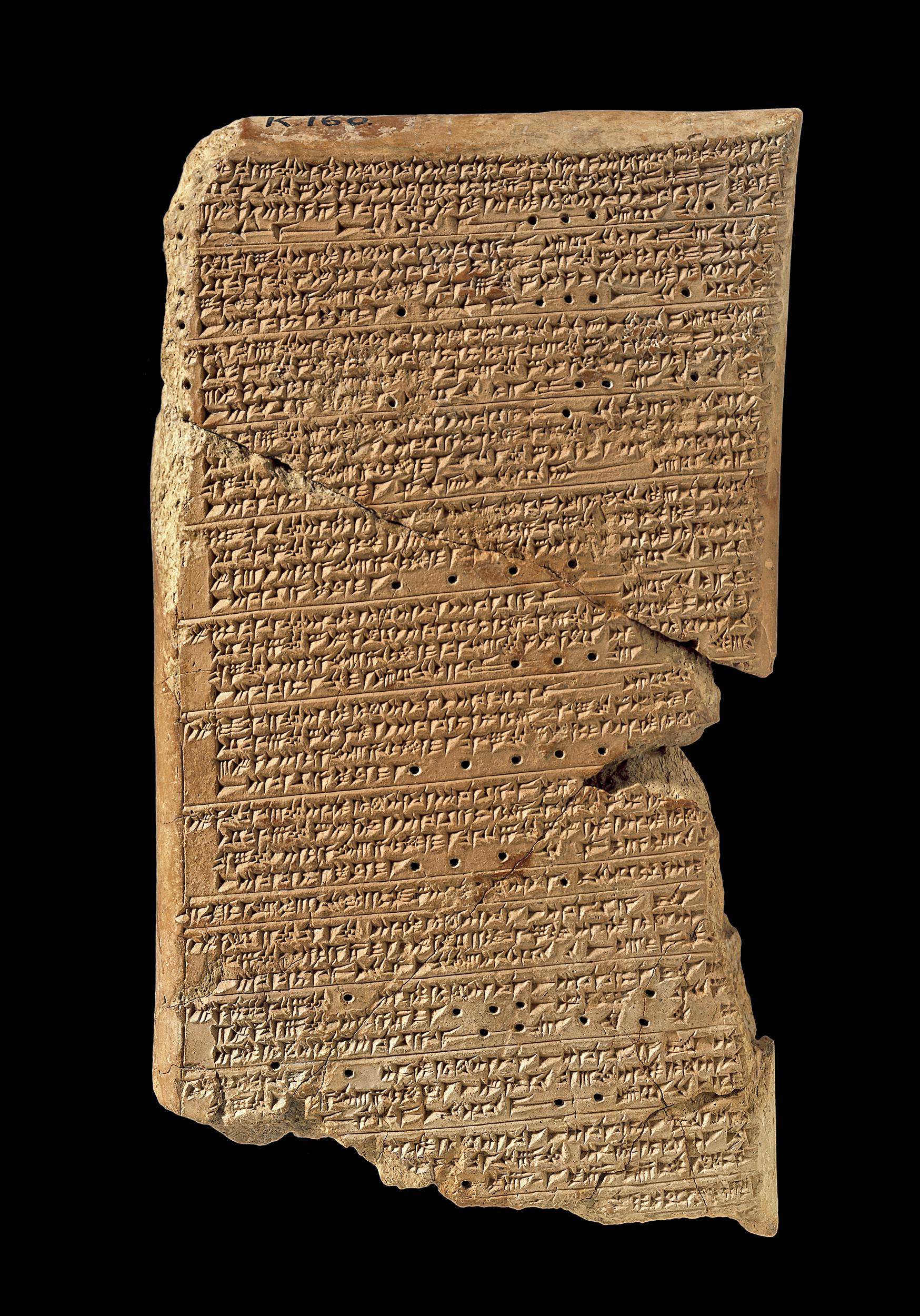

Cuneiform tablet with observations of Venus, Neo-Assyrian, 7th century B.C.E., from Nineveh, northern Iraq, clay, 17.14 x 9.20 x 2.22 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

This tablet is one of the most important (and controversial) cuneiform tablets for reconstructing Mesopotamian chronology before around 1400 B.C.E.

The text of the tablet is a copy, made at Nineveh in the seventh century B.C.E., of observations of the planet Venus made in the reign of Ammisaduqa, king of Babylon, about 1000 years earlier. Modern astronomers have used the details of the observations in an attempt to calculate the dates of Ammisaduqa. Ideally this process would also allow us to date the Babylonian rulers of the early second and late third millennium B.C.E. Unfortunately, however, there is much uncertainty in the dating because the records are so inconsistent. This has led to different chronologies being adopted with some scholars favoring a “high” chronology while others adopt a “middle” or “low” range of dates. There are good arguments for each of these.

Scribes