One of the most precious artifacts from Sumer, the Warka Vase was looted and almost lost forever.

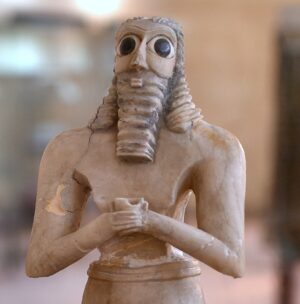

Picturing the ruler

So many important innovations and inventions emerged in the Ancient Near East during the Uruk period. One of these was the use of art to illustrate the role of the ruler and his place in society. The Warka Vase, c. 3000 B.C.E., was discovered at Uruk (Warka is the modern name, Uruk the ancient name), and is probably the most famous example of this innovation. In its decoration we find an example of the cosmology of ancient Mesopotamia.

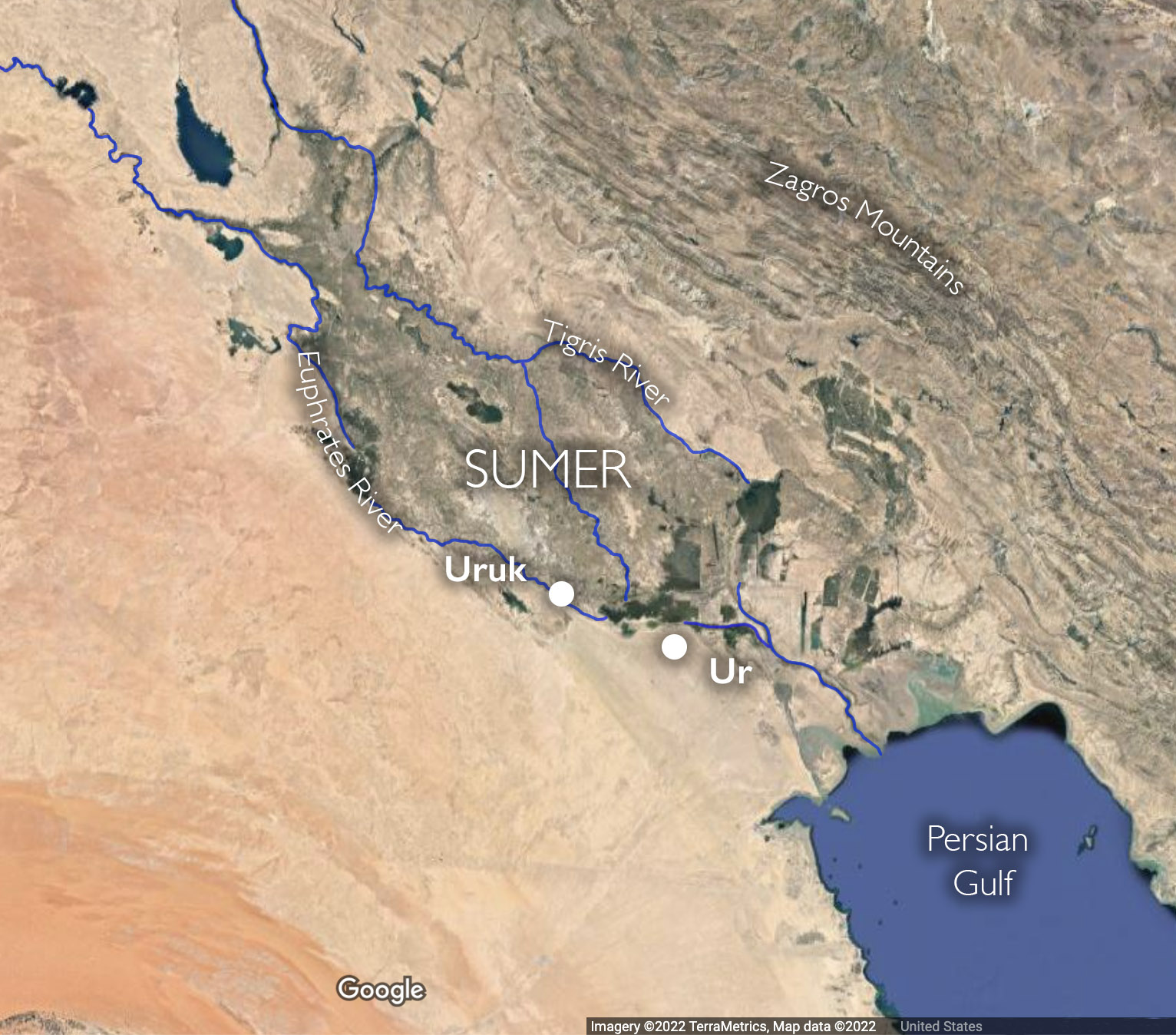

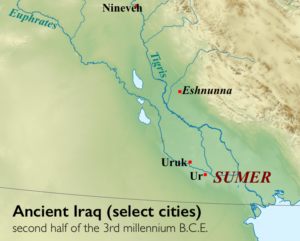

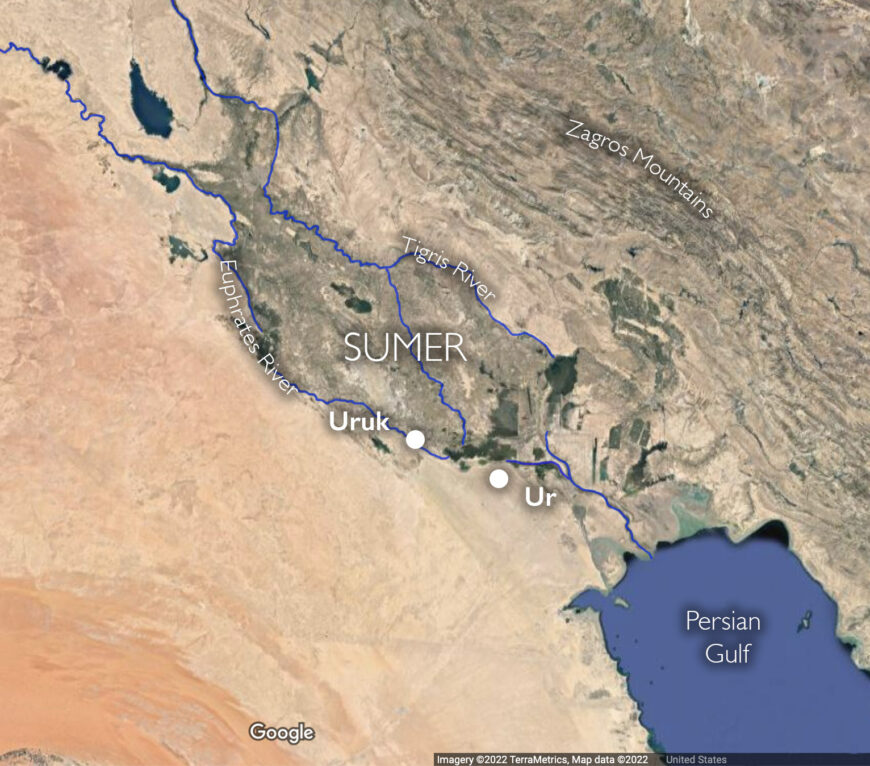

Map the ancient Near East (underlying map © Google)

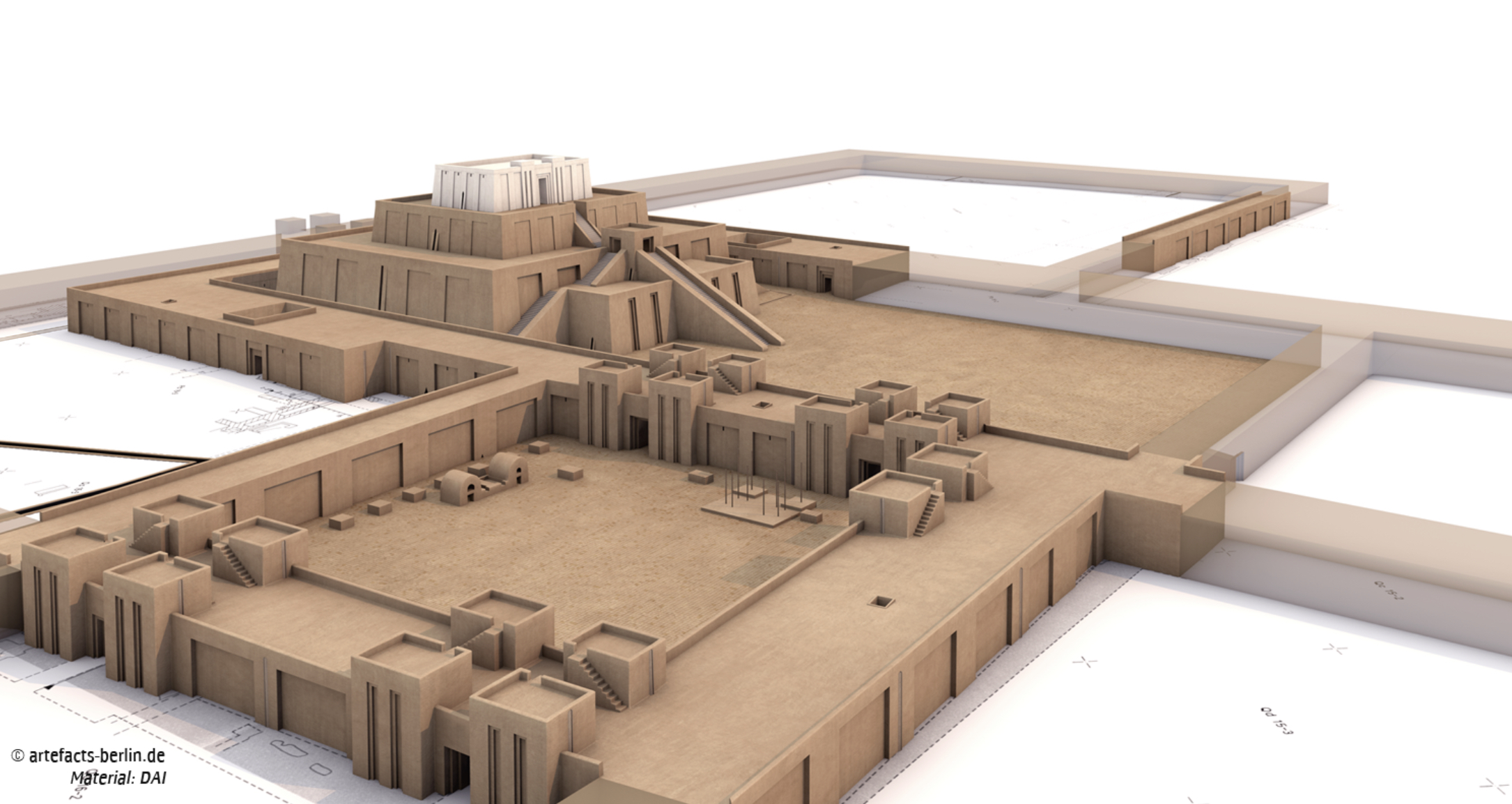

The vase, made of alabaster and standing over three feet high (just about a meter) and weighing some 600 pounds (about 270 kg), was discovered in 1934 by German excavators working at Uruk in a ritual deposit in the temple of Inanna, the goddess of love, fertility, and war and the main patron of the city of Uruk. It was one of a pair of vases found in the Inanna temple complex (but the only one on which the image was still legible) together with other valuable objects.

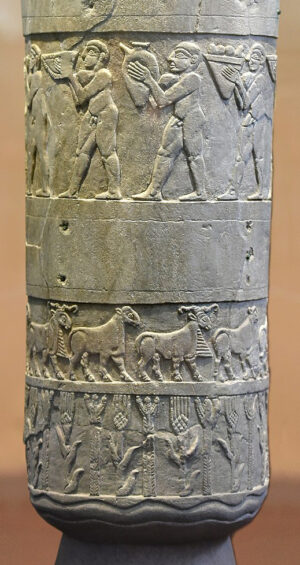

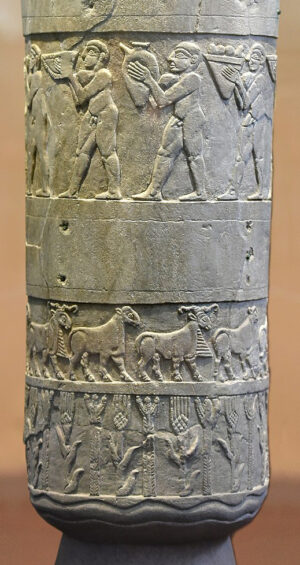

Bottom bands (detail), Warka (Uruk) Vase, Uruk, Late Uruk period, c. 3500–3000 B.C.E., 105 cm high (National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad; photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0)

Given the significant size of the Warka Vase, where it was found, the precious material from which it is carved and the complexity of its relief decoration, it was clearly of monumental importance, something to be admired and valued. Though known since its excavation as the Warka “Vase,” that term does little to express the sacredness of this object for the people who lived in Uruk five thousand years ago.

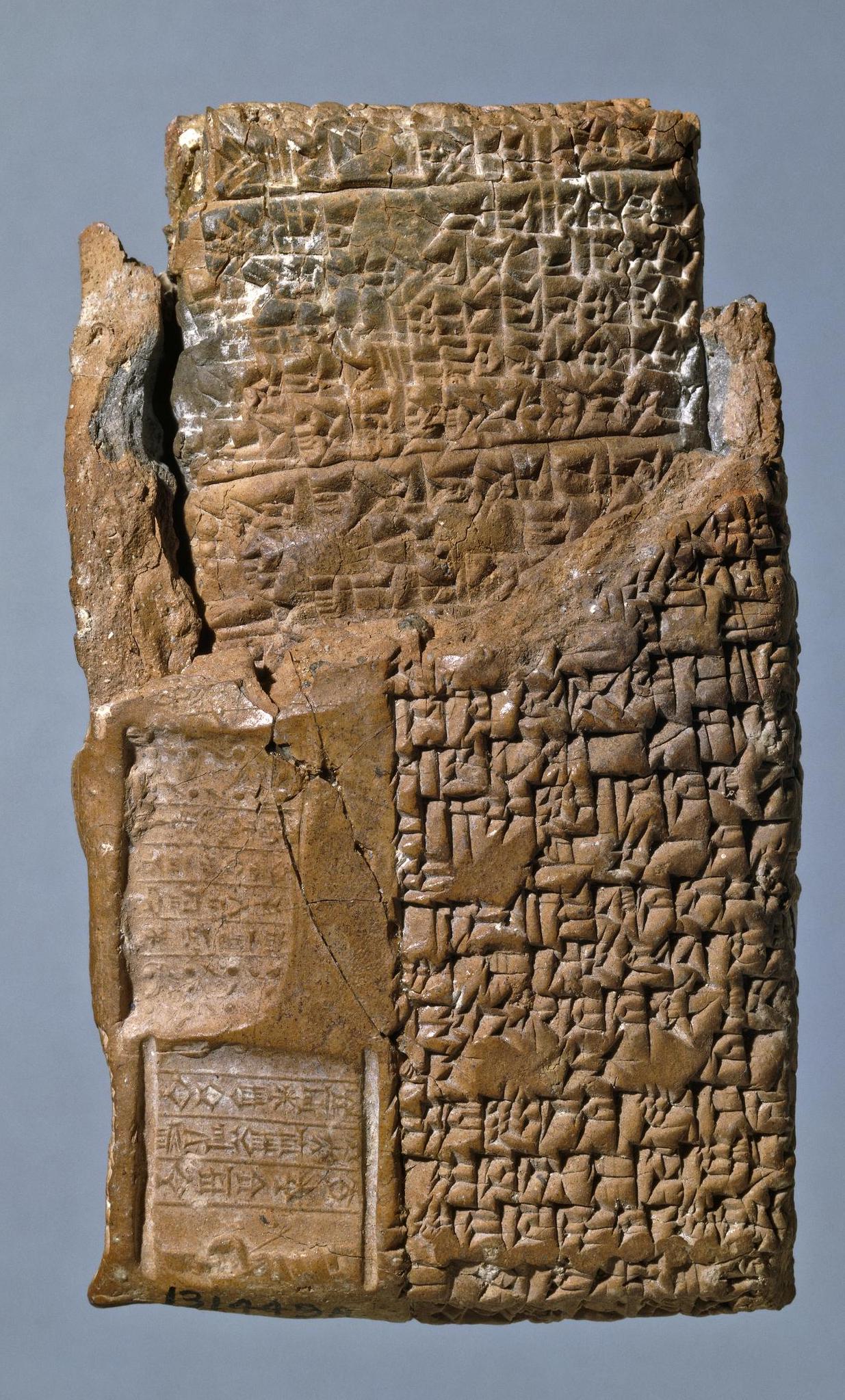

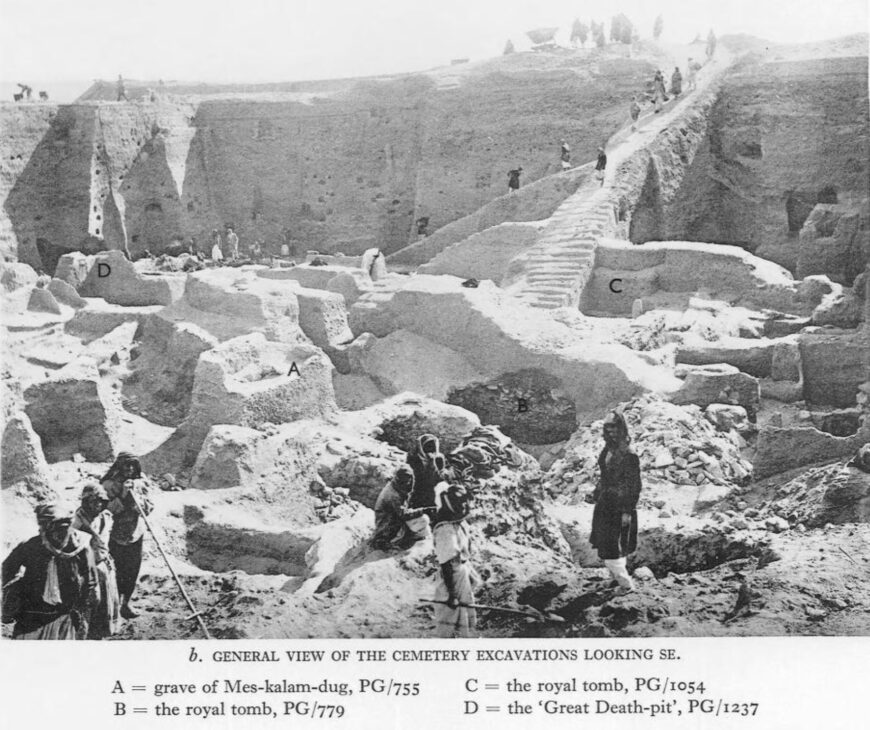

The relief carvings on the exterior of the vase run around its circumference in four parallel bands (or registers, as art historians like to call them) and develop in complexity from the bottom to the top.

Beginning at the bottom, we see a pair of wavy lines from which grow neatly alternating plants that appear to be grain (probably barley) and reeds, the two most important agricultural harvests of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in southern Mesopotamia. There is a satisfying rhythm to this alternation, and one that is echoed in the rhythm of the rams and ewes (male and female sheep) that alternate in the band above this. The sheep march to the right in tight formation, as if being herded—the method of tending this important livestock in the agrarian economy of the Uruk period.

The band above the sheep is a blank and might have featured painted decoration that has since faded away. Above this blank band, a group of nine identical men march to the left. Each holds a vessel in front of his face, and which appear to contain the products of the Mesopotamian agricultural system: fruits, grains, wine, and mead. The men are all naked and muscular and, like the sheep beneath them, are closely and evenly grouped, creating a sense of rhythmic activity. Nude figures in Ancient Near Eastern art are meant to be understood as humble and low status, so we can assume that these men are servants or enslaved individuals (the band above, displays the owners of the enslaved figures).

Drawing, top register, Warka (Uruk) Vase (reconstructing some missing areas), by Jo Wood, after M. Roaf, from Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen (Eisenbrauns, 2001), p. 17.

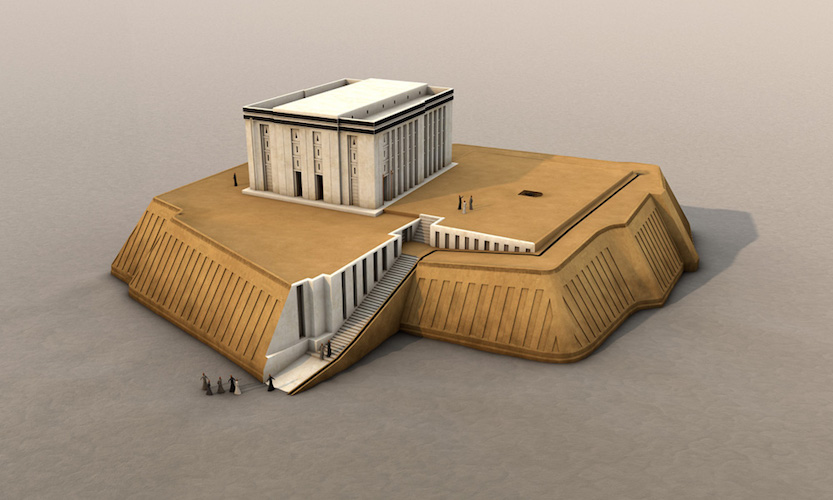

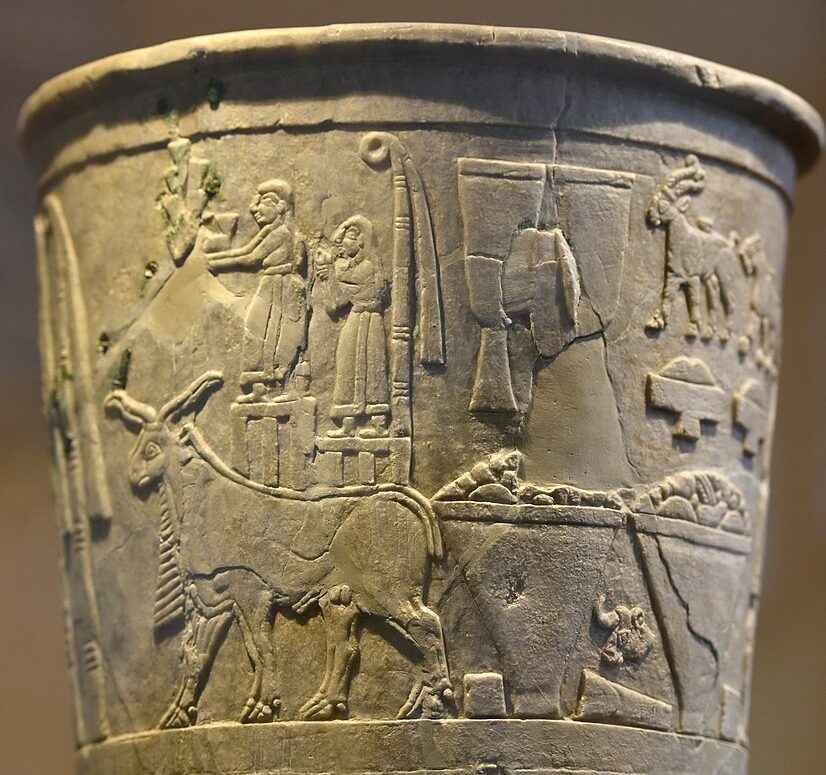

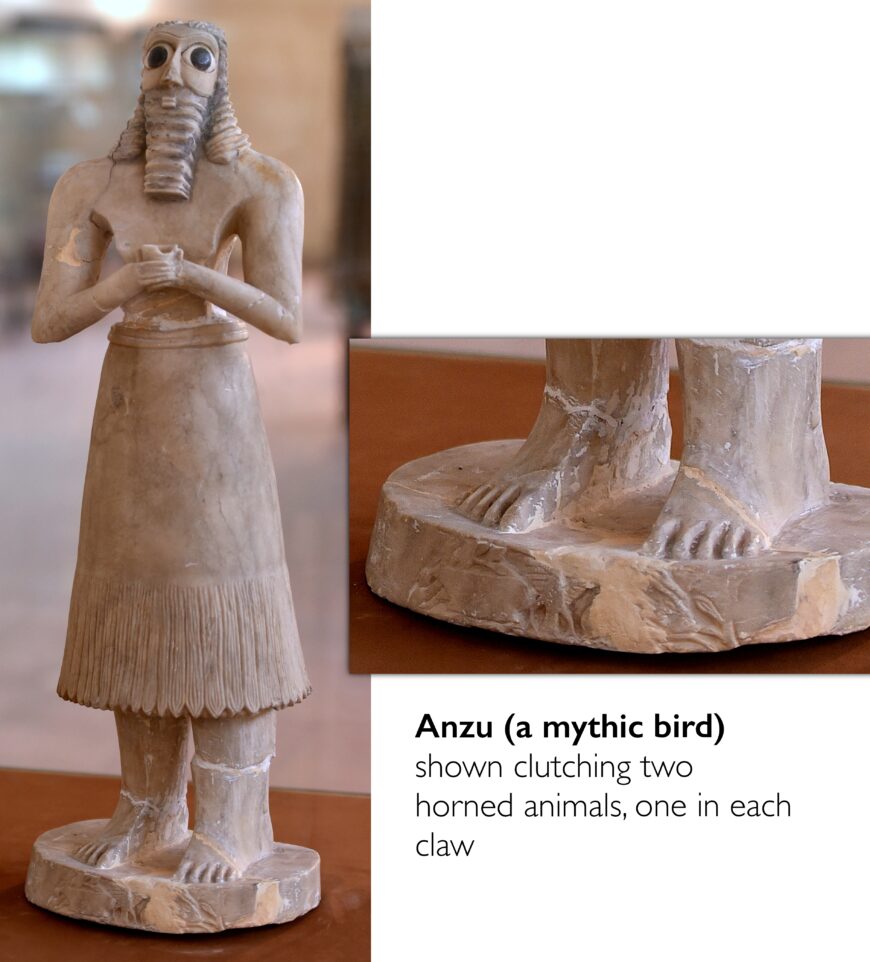

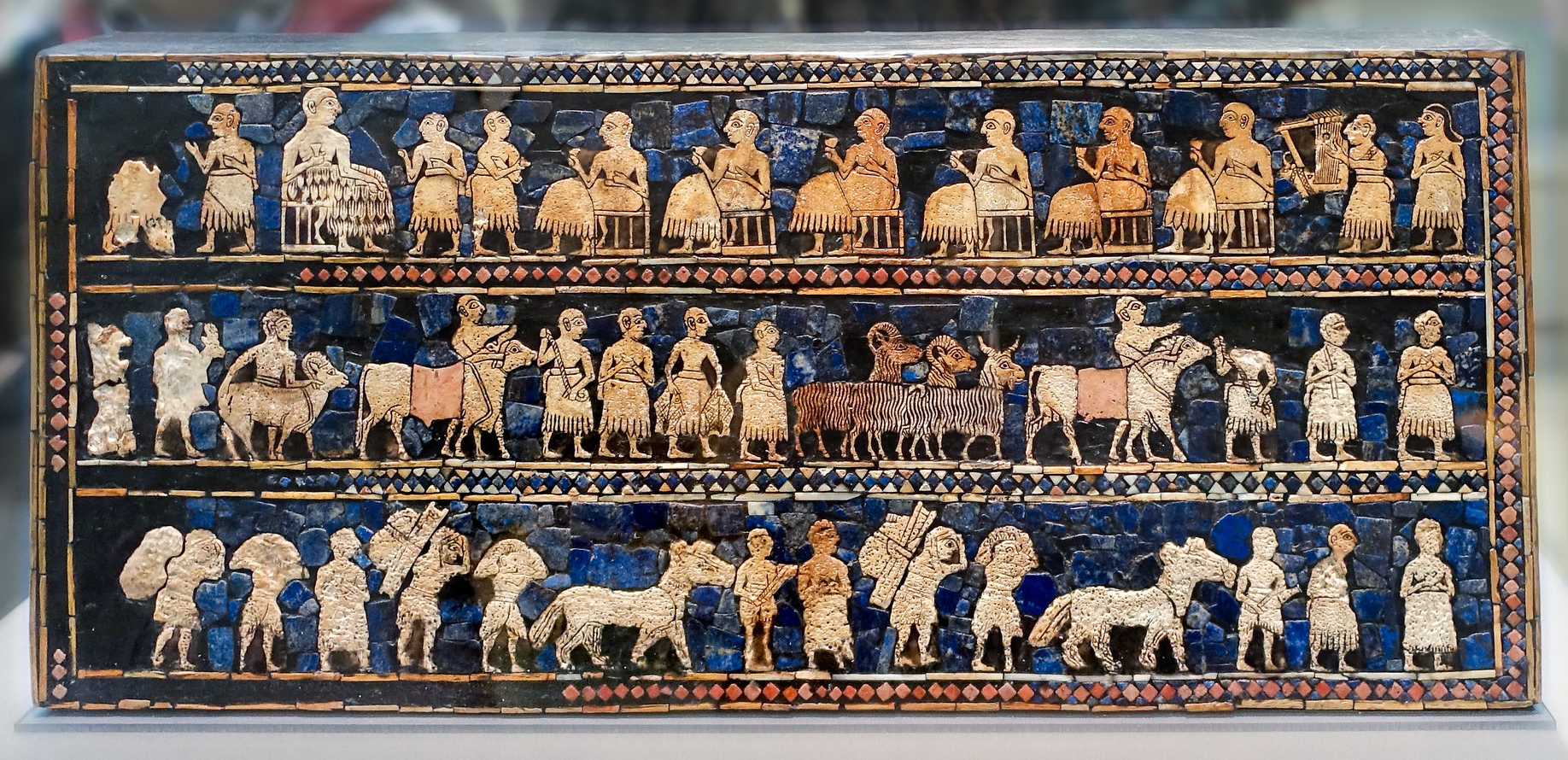

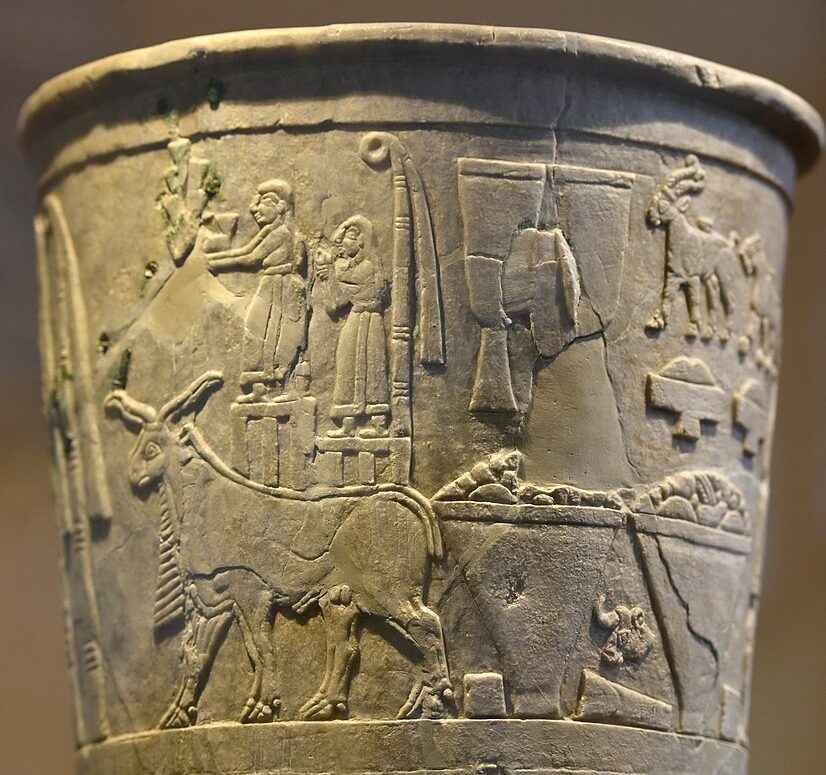

The top band of the vase is the largest, most complex, and least straightforward. It has suffered some damage but enough remains that the scene can be read. The center of the scene appears to depict a man and a woman who face each other. A smaller naked male stands between them holding a container of what looks like agricultural produce which he offers to the woman. The woman, identified as such by her robe and long hair, at one point had an elaborate crown on her head (this piece was broken off and repaired in antiquity).

Behind her are two reed bundles, symbols of the goddess Inanna, whom, it is assumed, the woman represents. The man she faces is nearly entirely broken off, and we are left with only the bottom of his long garment. However, men with similar robes are often found in contemporary seal stone engraving and based upon these, we can reconstruct him as a king with a long skirt, a beard and a head band. The tassels of his skirt are held by another smaller scaled man behind him, a steward or attendant to the king, who wears a short skirt.

Top band (detail), Warka (Uruk) Vase, Uruk, Late Uruk period, c. 3500–3000 B.C.E., 105 cm high (National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad; photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0)

The rest of the scene is found behind the reed bundles at the back of Inanna. There we find two-horned and bearded rams (one directly behind the other, so the fact that there are two can only be seen by looking at the hooves) carrying platforms on their backs on which statues stand. The statue on the left carries the cuneiform sign for EN, the Sumerian word for chief priest. The statue on the right stands before yet another Inanna reed bundle. Behind the rams is an array of tribute gifts including two large vases which look quite a lot like the Warka Vase itself.

What could this busy scene mean? The simplest way to interpret it is that a king (presumably of Uruk) is celebrating Inanna, the city’s most important divine patron. A more detailed reading of the scene suggests a sacred marriage between the king, acting as the chief priest of the temple, and the goddess—each represented in person as well as in statues. Their union would guarantee for Uruk the agricultural abundance we see depicted behind the rams. The worship of Inanna by the king of Uruk dominates the decoration of the vase. The top illustrates how the cultic duties of the Mesopotamian king as chief priest of the goddess, put him in a position to be responsible for and proprietor of, the agricultural wealth of the city state.

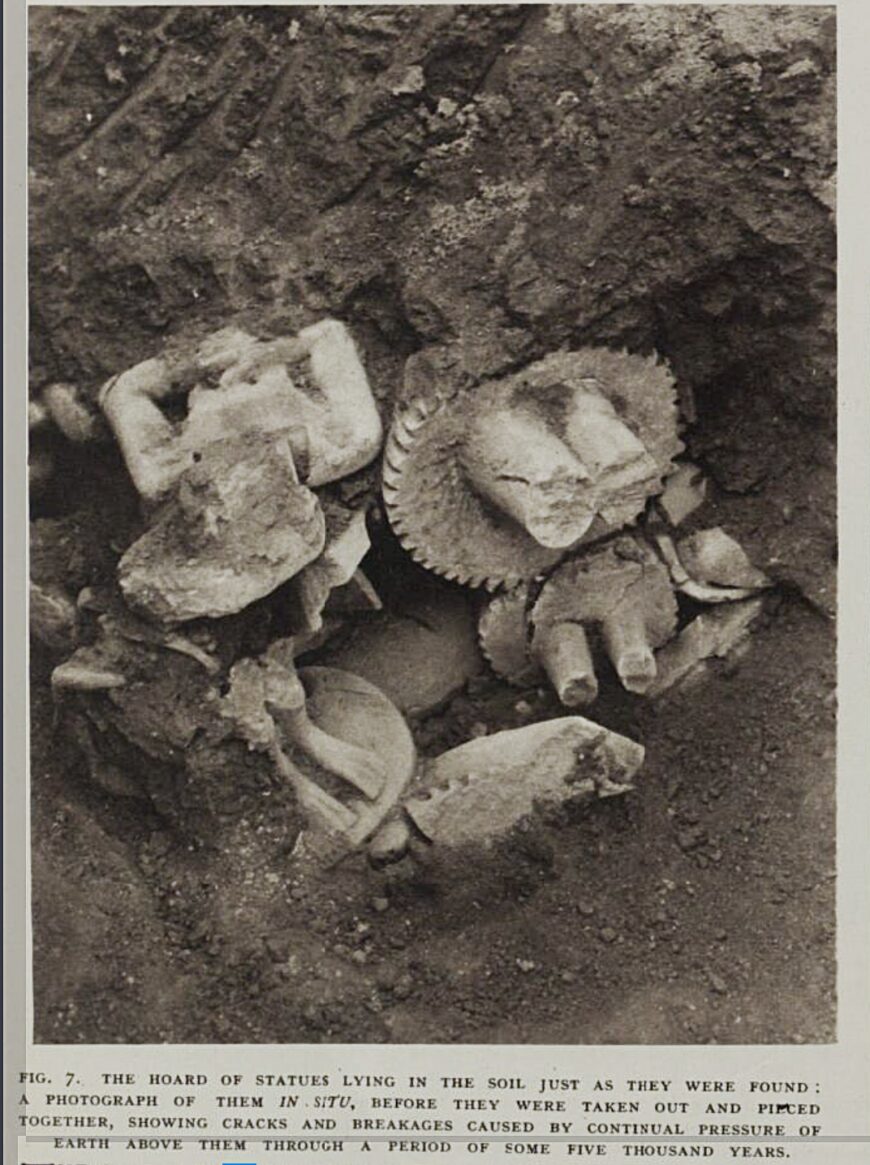

Broken-off foot of vase, tossed over, May 2003 (National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad; photo: Joanne Farchakh)

Backstory

The Warka Vase, one of the most important objects in the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad, was stolen in April 2003 with thousands of other priceless ancient artifacts when the museum was looted in the immediate aftermath of the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. The Warka Vase was returned in June of that same year after an amnesty program was created to encourage the return of looted items. The Guardian reported that “The United States army ignored warnings from its own civilian advisers that could have stopped the looting of priceless artifacts in Baghdad….”

Even before the invasion, looting was a growing problem, due to economic uncertainty and widespread unemployment in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War. According to Dr. Neil Brodie, Senior Research Fellow on the Endangered Archaeology of the Middle East and North Africa project at the University of Oxford, “In the aftermath of that war…as the country descended into chaos, between 1991 and 1994 eleven regional museums were broken into and approximately 3,000 artifacts and 484 manuscripts were stolen….” The vast majority of these have not been returned. And, as Dr. Brodie notes, the most important question may be why no concerted international action was taken to block the sale of objects looted from archaeological sites and cultural institutions during wartime.

Read more about endangered cultural heritage in the Near East in Smarthistory’s ARCHES (At Risk Cultural Heritage Education Series) section.

Additional resources

On looting in Iraq from SAFE (Saving Antiquities for Everyone)

Endangered Archaeology of the Middle East and North Africa project

Documentation on this object in “Lost Treasures from Iraq” from the Oriental Institute in Chicago

On looting in Iraq from The Antiquities Coalition

Uruk: The First City on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Neil Brodie, “The market background to the April 2003 plunder of the Iraq National Museum,” The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq, edited by Peter Stone and Joanne Farchakh Bajjaly (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2008), pp. 41–54.

Neil Brodie, “Iraq 1990–2004 and the London antiquities market,” Archaeology, Cultural Heritage, and the Antiquities Trade, edited by Neil Brodie, Morag Kersel, Christina Luke and Katheryn Walker Tubb (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006), pp. 206–26.

Neil Brodie, “Focus on Iraq: Spoils of War,” Archaeology (from the Archaeological Institute of America), volume 56, number 4 (July/August 2003).

Lauren Sandler, “The Thieves of Baghdad,” The Atlantic, November 2004.

The Guardian, “US army was told to protect looted museum,” April 20, 2003.