Babylonia, an Introduction

On the river Euphrates

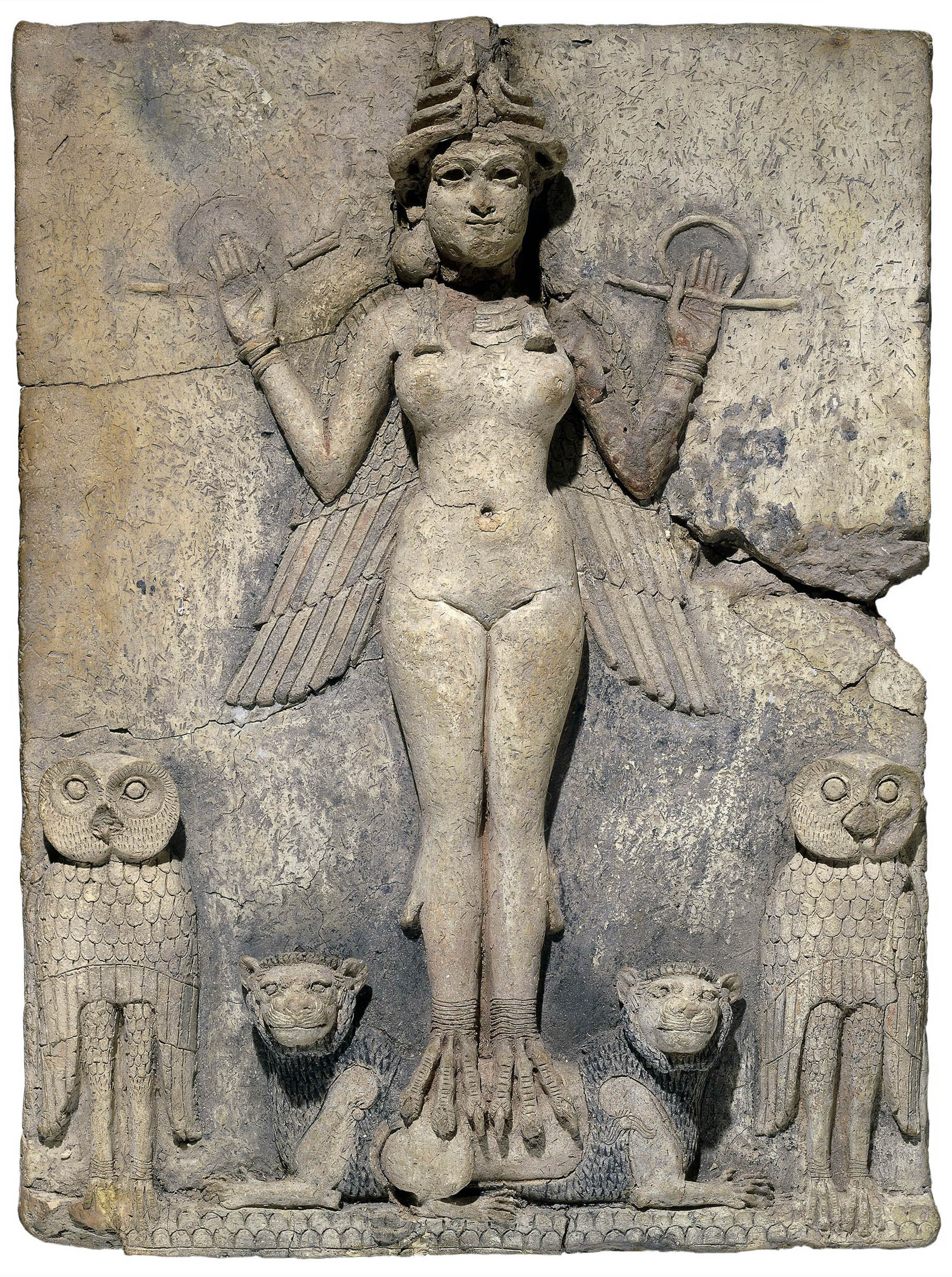

The city of Babylon on the river Euphrates in southern Iraq is mentioned in documents of the late third millennium B.C.E. and first came to prominence as the royal city of King Hammurabi. He established control over many other kingdoms stretching from the Persian Gulf to Syria. The British Museum holds one of the iconic artworks of this period, the so-called “Queen of the Night.”

From around 1500 B.C.E. a dynasty of Kassite kings took control in Babylon and unified southern Iraq into the kingdom of Babylonia. The Babylonian cities were the centers of great scribal learning and produced writings on divination, astrology, medicine and mathematics. The Kassite kings corresponded with the Egyptian Pharaohs as revealed by cuneiform letters found at Amarna in Egypt, now in the British Museum.

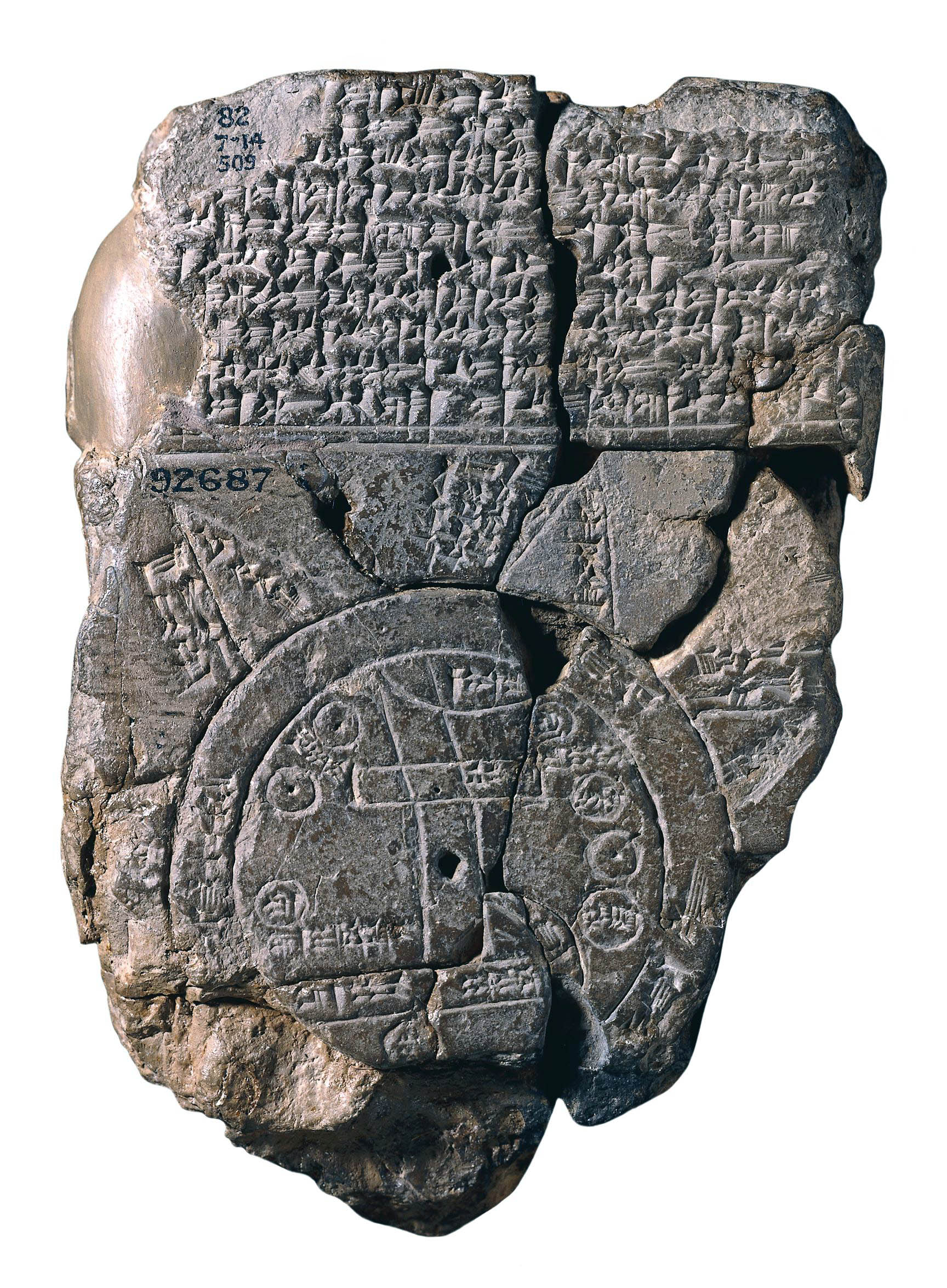

Babylonia had an uneasy relationship with its northern neighbor Assyria and opposed its military expansion. In 689 B.C.E. Babylon was sacked by the Assyrians but as the city was highly regarded it was restored to its former status soon after. Other Babylonian cities also flourished; scribes in the city of Sippar probably produced the famous Map of the World.

Babylonian kings

After 612 B.C.E. the Babylonian kings Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II were able to claim much of the Assyrian empire and rebuilt Babylon on a grand scale. Nebuchadnezzar II rebuilt Babylon in the sixth century B.C.E. and it became the largest ancient settlement in Mesopotamia. There were two sets of fortified walls and massive palaces and religious buildings, including the central ziggurat tower. Nebuchadnezzar is also credited with the construction of the famous “Hanging Gardens.” However, the last Babylonian king Nabonidus was defeated by Cyrus II of Persia and the country was incorporated into the vast Achaemenid Persian Empire.

New threats

Babylon remained an important center until the third century B.C.E., when Seleucia-on-the-Tigris was founded about ninety kilometers to the northeast. Under Antiochus I, the new settlement became the official Royal City and the civilian population was ordered to move there. Nonetheless a village existed on the old city site until the eleventh century A.D. Babylon was excavated by Robert Koldewey between 1899 and 1917 on behalf of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. Since 1958, the Iraq Directorate-General of Antiquities has carried out further investigations. Unfortunately, the earlier levels are inaccessible beneath the high water table. Since 2003, our attention has been drawn to new threats to the archaeology of Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq.

For two thousand years the myth of Babylon has haunted the European imagination. The Tower of Babel and the Hanging Gardens, Belshazzar’s Feast and the Fall of Babylon have inspired artists, writers, poets, philosophers and film makers.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Additional resources

Read a chapter in our textbook, Reframing Art History, about rethinking how we approach the art of the Ancient Near East.

Ancient Babylon: excavations, restorations and modern tourism.

Stele of Hammurabi

Law is at the heart of modern civilization, and is often based on principles listed here from nearly 4,000 years ago.

Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi, basalt, Babylonian, 1792–50 B.C.E. (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Hammurabi of the city-state of Babylon conquered much of northern and western Mesopotamia and, by 1776 B.C.E., he was the most far-reaching leader of Mesopotamian history, describing himself as “the king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient.” Documents show Hammurabi was a classic micro-manager, concerned with all aspects of his rule, and this is seen in his famous legal code, which survives in partial copies on this stele in the Louvre and on clay tablets. We can also view this as a monument presenting Hammurabi as an exemplary king of justice.

What is interesting about the representation of Hammurabi on the legal code stele is that he is seen as receiving the laws from the god Shamash, who is seated, complete with thunderbolts coming from his shoulders. The emphasis here is Hammurabi’s role as pious theocrat, and that the laws themselves come from the god.

Additional resources

This work at the Louvre.

Read an English translation of the Code of Hammurabi on Yale’s ‘The Avalon Project.’

Learn more about record keeping with clay tablets.

Read a chapter in our textbook, Reframing Art History, about rethinking how we approach the art of the Ancient Near East.

More Smarthistory images…

The Code of Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi is one of the oldest deciphered writings of length in the world, and features a code of law from ancient Babylon in Mesopotamia. Written in about 1754 BCE by the sixth king of Babylon, Hammurabi, the Code was written on stone stele and clay tablets. It consisted of 282 laws, with punishments that varied based on social status (slaves, free men, and property owners). It is most famous for the “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” (lex talionis) form of punishment. Other forms of codes of law had been in existence in the region around this time, including the Code of Ur-Nammu, king of Ur (c. 2050 BCE), the Laws of Eshnunna (c. 1930 BCE) and the codex of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (c. 1870 BCE).

The laws were arranged in groups, so that citizens could easily read what was required of them. Some have seen the Code as an early form of constitutional government, and as an early form of the presumption of innocence, and the ability to present evidence in one’s case. Intent was often recognized and affected punishment, with neglect severely punished. Some of the provisions may have been codification of Hammurabi’s decisions, for the purpose of self-glorification. Nevertheless, the Code was studied, copied, and used as a model for legal reasoning for at least 1500 years after.

The prologue of the Code features Hammurabi stating that he wants “to make justice visible in the land, to destroy the wicked person and the evil-doer, that the strong might not injure the weak.” Major laws covered in the Code include slander, trade, slavery, the duties of workers, theft, liability, and divorce. Nearly half of the code focused on contracts, such as wages to be paid, terms of transactions, and liability in case of property damage. A third of the code focused on household and family issues, including inheritance, divorce, paternity and sexual behavior. One section establishes that a judge who incorrectly decides an issue may be removed from his position permanently. A few sections address military service.

One of the most well-known sections of the Code was law #196: “If a man destroy the eye of another man, they shall destroy his eye. If one break a man’s bone, they shall break his bone. If one destroy the eye of a freeman or break the bone of a freeman he shall pay one gold mina. If one destroy the eye of a man’s slave or break a bone of a man’s slave he shall pay one-half his price.”

The Social Classes

Under Hammurabi’s reign, there were three social classes. The amelu was originally an elite person with full civil rights, whose birth, marriage and death were recorded. Although he had certain privileges, he also was liable for harsher punishment and higher fines. The king and his court, high officials, professionals and craftsmen belonged to this group. The mushkenu was a free man who may have been landless. He was required to accept monetary compensation, paid smaller fines and lived in a separate section of the city. The ardu was a slave whose master paid for his upkeep, but also took his compensation. Ardu could own property and other slaves, and could purchase his own freedom.

Women’s Rights

Women entered into marriage through a contract arranged by her family. She came with a dowry, and the gifts given by the groom to the bride also came with her. Divorce was up to the husband, but after divorce he then had to restore the dowry and provide her with an income, and any children came under the woman’s custody. However, if the woman was considered a “bad wife” she might be sent away, or made a slave in the husband’s house. If a wife brought action against her husband for cruelty and neglect, she could have a legal separation if the case was proved. Otherwise, she might be drowned as punishment. Adultery was punished with drowning of both parties, unless a husband was willing to pardon his wife.

Discovery of the Code

Archaeologists, including Egyptologist Gustave Jequier, discovered the code in 1901 at the ancient site of Susa in Khuzestan; a translation was published in 1902 by Jean-Vincent Scheil. A basalt stele containing the code in cuneiform script inscribed in the Akkadian language is currently on display in the Louvre, in Paris, France. Replicas are located at other museums throughout the world.

CC licensed content, Shared previously