Predynastic and Early Dynastic Art of Ancient Egypt

Introduction to the Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods

Standing at the cusp of one of the longest-lived and most influential cultures that ever existed, the people living in the Nile valley during the fifth and fourth millennia B.C.E. laid the foundation for everything to come. During this era, powerful townships developed unique local cult practices and ruling organizations. The Two Lands (Upper and Lower Egypt) became united around 3000 B.C.E. under a single king, Narmer (or Menes), who ruled as the first king of Upper and Lower Egypt. Already in this early period, many of the distinct characteristics of Egyptian culture, including kingship ideology, writing system, social structure, religious beliefs, and modes of artistic representation were introduced and codified.

Predynastic Period (c. 5000–3000 B.C.E.)

This period saw the rise of several powerful towns, especially Abydos, Naqada, and Nekhen (commonly called Hierakonpolis) and a possible unified southern kingdom. Hieroglyphic writing emerged, probably for administrative and ritual purposes to support the rulers of these southern towns. The earliest known texts were short labels and captions, but the writing system developed rapidly and helped frame the dynamic civilization that emerged along the Nile.

The ivory handle includes a thumb rest for a right-handed user. Carved rows of minuscule animals—including elephants, lions, a giraffe, and sheep—cover both surfaces of the handle. Ritual knife, c. 3300–3100 B.C.E., Pre-dynastic period, flint, elephant ivory, excavated Abu Zaidan, Egypt (Brooklyn Museum)

Copper tools and fine flint blades demonstrate the technological level of the period. Some of these flint blades sport handles with imagery that is decidedly Near Eastern in origin; these and other indications like the existence of objects crafted of lapis lazuli (a material from Afghanistan) point to active trade between Egypt and western Asia at this time.

The craft of sculpture exploded with large-scale figures carved in stone, such as those excavated at Koptos. By the end of this era, burials sometimes included small coffins of basketwork or clay.

King Den’s sandal label, 1st dynasty, ivory, found at Abydos, Upper Egypt, 4.5 x 5.3 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Early Dynastic Period (c. 3000–2686 B.C.E.)

The unification of north and south under a single ruler occurred c. 3000 B.C.E. Over the next couple of centuries, disparate townships and local cultures were bound together under the control of the single king, and a dynamic stratified society evolved. The second king to rule the newly unified Egypt introduced the important ritualized census called the “Followers of Horus.” In this annual or bi-annual event, the king and his court would tour the different regions of the country, called nomes, taking count of assets like cattle, grain, and goods. These counts would then be used to determine taxation required from each region, with proceeds being gathered to central storehouses for later distribution. These regular visits reinforced the king’s power throughout the country.

A complex pantheon of deities was already evident at this time. Local worship of Ra, Horus, Ptah, and Seth and many cult shrines were first established in this era. Items excavated from royal tombs included small labels, originally attached to grave goods, with scenes showing the king performing ritual actions for a variety of deities and may record actual visits to divine shrines associated with local cults. On the ivory label of king Den above, the ruler is shown smiting his restrained enemy before a cult object at the far right. The king’s name is clearly written in front of his face, surrounded by a falcon-surmounted rectangular form known as a serekh. He wears a prototype royal headdress with an upright cobra (called a uraeus) at his brow. The opposite side of this label is inscribed with a pair of sandals, indicating the type of grave item that it was originally attached to.

Narmer Macehead, Early Dynastic Period, c. 31st century B.C.E., found in Hierakonopolis (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

Other artifacts from this period include massive ceremonial mace heads, palettes, and stelae carved with scenes that commemorate important events.

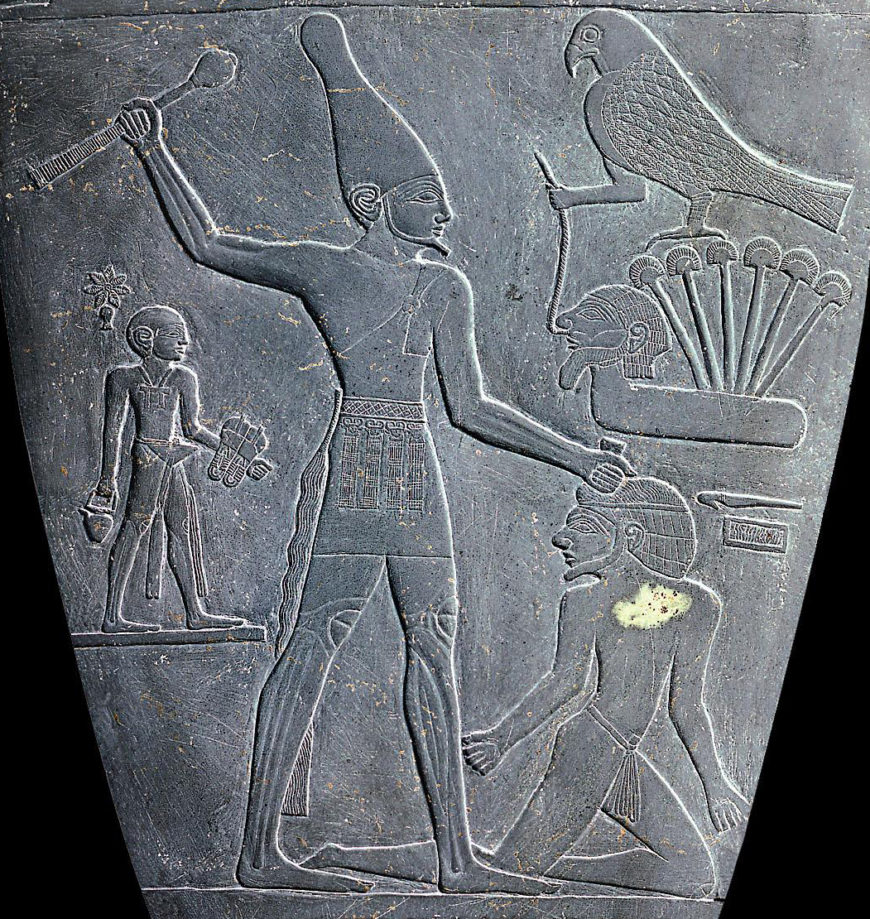

Palette of King Narmer, c. 3000–2920 B.C.E., Predynastic Egypt, greywacke (slate), from Hierakonpolis, 2′ 1″ high (Egyptian Museum, Cairo)

Map of Ancient Egypt (modified) (original image: Jeff Dahl, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A number of these votive objects, such as the Narmer palette, were discovered together in a cache excavated in the temple precinct at Hierakonpolis. There seems to be an intentional blending of actual, historical events and ritual elements in the decoration of these objects, an early indication of the tendency in ancient Egypt to blur the lines between the physical and spiritual worlds.

The goddesses Nekhbet and Wadjet (referred to as the Two Ladies), representing Upper and Lower Egypt respectively begin to appear prominently on ritual objects, as do both the White Crown of the south and the Red Crown of the north—all symbols of the Two Lands that would be used for millennia to come.

Many artistic conventions were established during this period, as was much of the royal iconography that expressed the ideology of kingship. This includes specific poses, items of clothing and regalia, and image associations, such as the smiting pose, the wearing of various crowns, and the use of bull imagery as an analogy for the king, all of which are visible on the Narmer Palette.

With the First Dynasty, focus turned from south to north and the city of Memphis was selected as the capital of the united Egypt. This move also shifted the royal cemeteries from Abydos north to the site of Saqqara. Towards the end of this era, there is a change in focus from the king honoring the gods in their local shrines to a system where the deities came together to sanctify the king and aid his journey in the afterlife.

| Period |

Dates |

| Predynastic |

c. 5000–3000 B.C.E. |

| Early Dynastic |

c. 3000–2686 B.C.E. |

| Old Kingdom (the ‘pyramid age’) |

c. 2686–2150 B.C.E. |

| First Intermediate Period |

c. 2150–2030 B.C.E. |

| Middle Kingdom |

c. 2030–1640 B.C.E. |

| Second Intermediate Period

(Northern Delta region ruled by Asiatics) |

c. 1640–1540 B.C.E. |

| New Kingdom |

c. 1550–1070 B.C.E. |

| Third Intermediate Period |

c. 1070–713 B.C.E. |

| Late Period

(a series of rulers from foreign dynasties, including Nubian, Libyan, and Persian rulers) |

c. 713–332 B.C.E. |

| Ptolemaic Period

(ruled by Greco-Romans) |

c. 332–30 B.C.E. |

| Roman Period |

c. 30 B.C.E.–395 C.E. |

Additional resources:

Read an overview of Egyptian chronology and historical framework

Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period

Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period

New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period

Late Period and Ptolemaic and Roman Periods

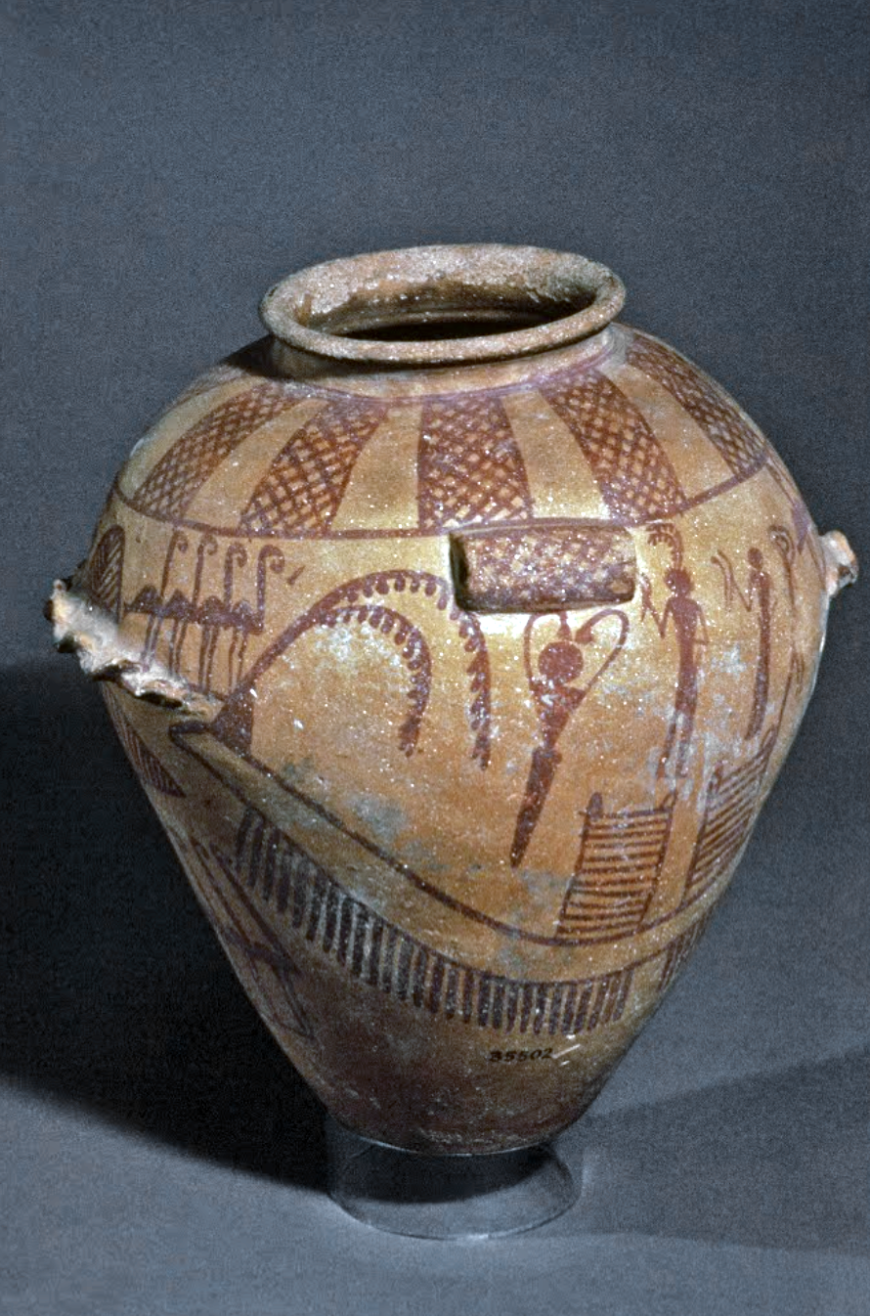

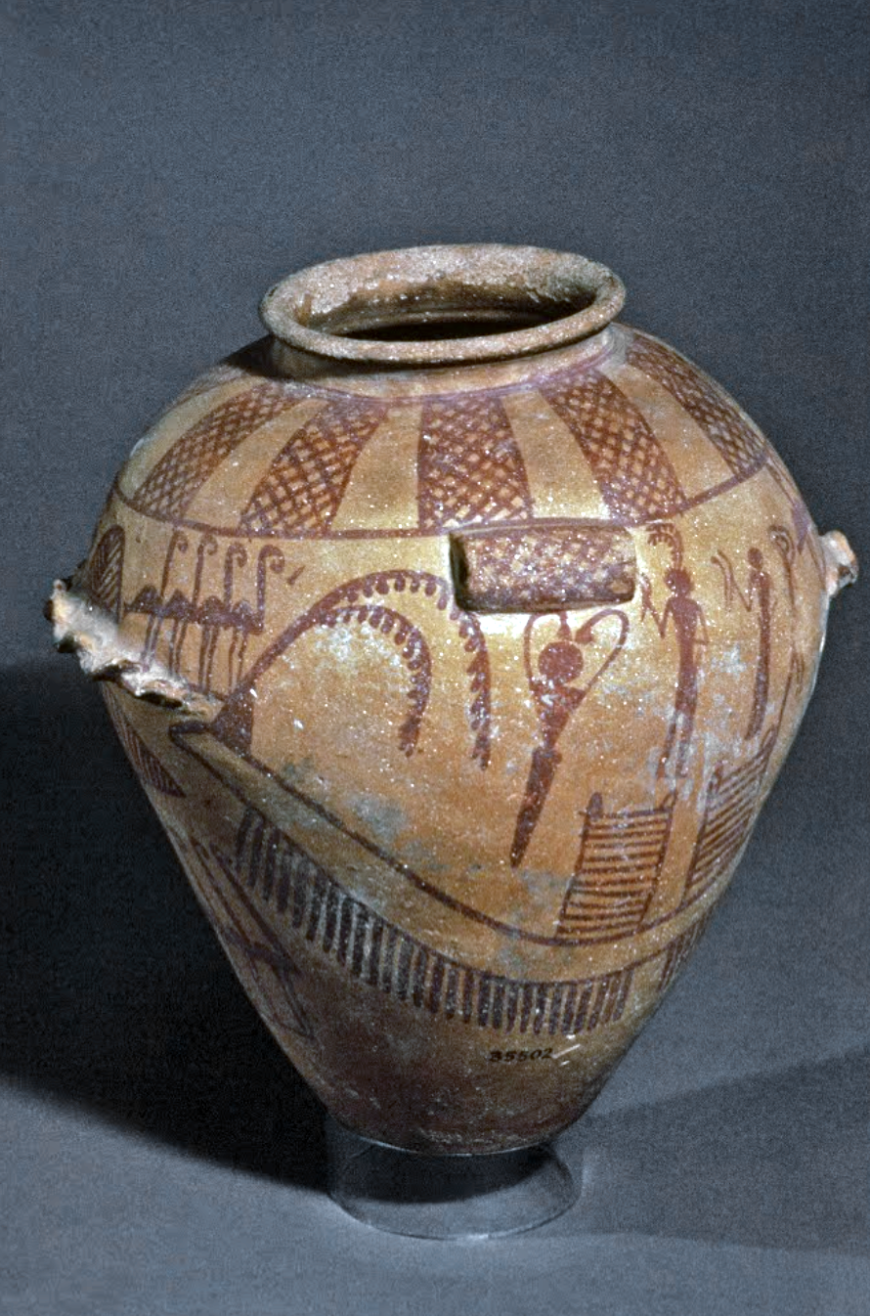

Decorated Jar from the Predynastic Period

Decorated jar, c. 3500 B.C.E., predynastic period (Naqada II), pottery, found in a tomb in el-Amra, Egypt, 22.5 cm in diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Light-colored pots like this one, made of marl clay mined from desert wadis and painted with red ochre pigment, are known as Decorated ware. They are characteristic of later Predynastic times (c. 3500–3200 B.C.E.). The most intriguing are those painted with boats and human figures. This pot comes from the tomb of a young woman, at el-Amra in Middle Egypt, but pots showing boats have been found throughout Egypt and into Nubia. The boats are always strikingly similar, with a curved hull, a large number of oars, and two cabins in the center. Attached to one of the cabins (usually the right-side one) is a pole bearing an emblem, which may be the symbol of a god or a place.

Decorated jar, c. 3500 B.C.E., predynastic period (Naqada II), pottery, found in a tomb in el-Amra, Egypt, 22.5 cm in diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

A boat is drawn on each side of this pot. Above them are stylized human figures: a dancing woman with her hands raised over her head, and two men holding clappers or casinets. The woman is perhaps a goddess or priestess, and the scenes on this pot can be understood as episodes in a ritual or ceremony. On one side, the woman is called forth from the boat by the playing of one man, while the other man helps to raise her up. On the other side, both men beat out the tune, as she dances for them, conferring her blessings on them. The feathers worn in the hair of one man represents victory.

The full meaning of these scenes is still debated. Decorated ware is found mainly in graves, so the paintings may depicts the funeral procession. However because similar scenes are also known from desert rock art, the rituals may more broadly be associated with fertility and rebirth of the both humans and the land. Such concerns were important throughout Egyptian history. The ostriches, known for their large eggs, and the small bushes, also shown on the pot reinforce the message of fertility and rebirth.

The lack of variation in style, shape, and motifs of decorated pottery suggests that these vessels were manufactured at a limited number of workshops; close scrutiny has even identified the work of individual artists. The artist who painted this pot probably made at least two others found in cemeteries up to 60 km away. The development of a trade and transport system to distribute pottery was one of the critical steps towards the formation of Dynastic civilization.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Palette of Narmer

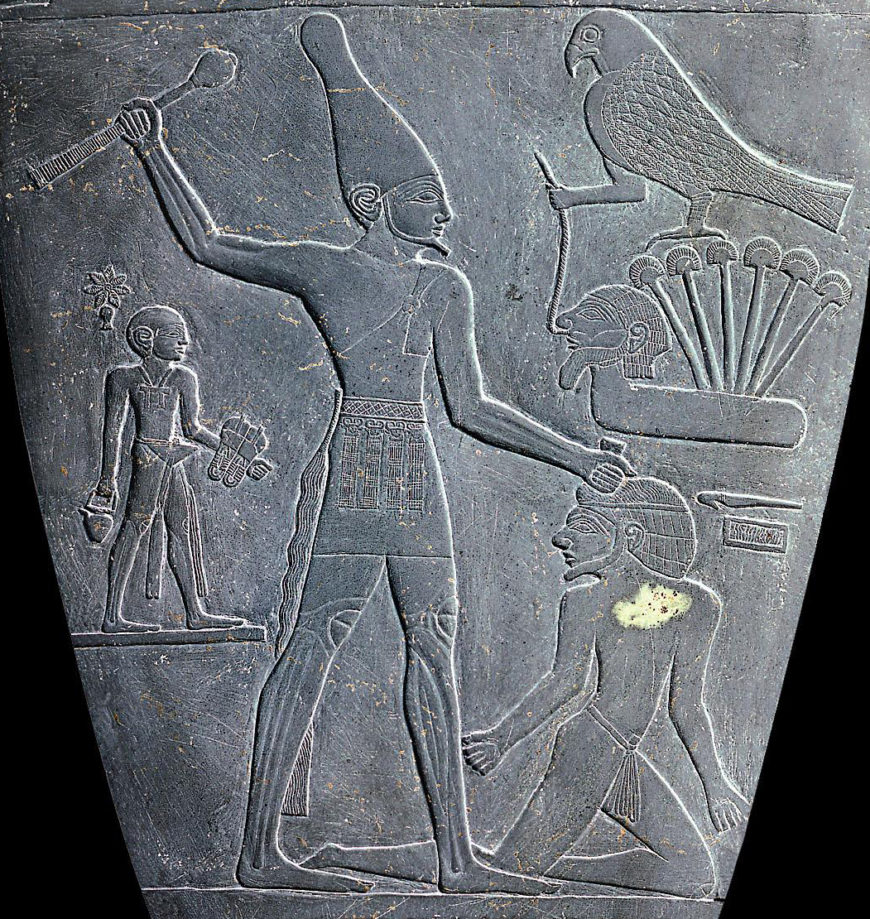

Palette of King Narmer, from Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Predynastic, c. 3000–2920 B.C.E., slate, 2′ 1″ high (Egyptian Museum, Cairo)

Vitally important, but difficult to interpret

Some artifacts are of such vital importance to our understanding of ancient cultures that they are truly unique and utterly irreplaceable. The gold mask of Tutankhamun was allowed to leave Egypt for display overseas; the Narmer Palette, on the other hand, is so valuable that it has never been permitted to leave the country.

Discovered among a group of sacred implements ritually buried in a deposit within an early temple of the falcon god Horus at the site of Hierakonpolis (a capital of Egypt during the Predynastic period), this large ceremonial object is one of the most important artifacts from the dawn of Egyptian civilization. The beautifully carved palette, 63.5 cm (more than 2 feet) in height and made of smooth greyish-green siltstone, is decorated on both faces with detailed low relief. These scenes show a king, identified by name as Narmer, and a series of ambiguous scenes that have been difficult to interpret and have resulted in a number of theories regarding their meaning.

The high quality of the workmanship, its original function as a ritual item dedicated to a god, and the complexity of the imagery clearly indicate that this was a significant object, but a satisfactory interpretation of the scenes has been elusive.

What was the palette used for?

The object itself is a monumental version of a type of daily use item commonly found in the Predynastic period—palettes were generally flat, minimally decorated stone objects used for grinding and mixing minerals for cosmetics. Dark eyeliner was an essential aspect of life in the sun-drenched region; like the dark streaks placed under the eyes of modern athletes, black cosmetic lines around the eyes served to reduce glare. Basic cosmetic palettes were among the typical grave goods found during this early era.

In addition to these simple, purely functional, palettes however, there were also a number of larger, far more elaborate palettes created in this period. These objects still served the function of being a ground for grinding and mixing cosmetics, but they were also carefully carved with relief sculpture. Many of the earlier palettes display animals—some real, some fantastic—while later examples, like the Narmer Palette, focus on human actions. Research suggests that these decorated palettes were used in temple ceremonies, perhaps to grind or mix makeup to be ritually applied to the image of the god. Later temple rituals included elaborate daily ceremonies involving the anointing and dressing of divine images; these palettes likely indicate an early incarnation of this process.

A ceremonial object, ritually buried

The Narmer Palette was discovered in 1898 by James Quibell and Frederick Green. It was found with a collection of other objects that had been used for ceremonial purposes and then ritually buried within the temple at Hierakonpolis.

Two Dogs Palette, Hierakonpolis, Egypt c. 3100 B.C.E. (Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

Temple caches of this type are not uncommon. There was a great deal of focus on ritual and votive objects (offerings to the gods) in temples. Every ruler, elite individual, and anyone else who could afford it donated items to the temple to show their piety and increase their connection to the deity. After a period of time, the temple would be full of these objects and space needed to be made for new votive donations. However, since they had been dedicated to a temple and sanctified, the old items that needed to be cleared out could not simply be thrown away or sold. Instead, the general practice was to bury them in a pit dug under the temple floor. Often, these caches include objects from a range of dates and a mix of types, from royal statuary to furniture.

The “Main Deposit” at Hierakonpolis, where the Narmer Palette was discovered, contained many hundreds of objects, including a number of large relief-covered ceremonial mace-heads, ivory statuettes, carved knife handles, figurines of scorpions and other animals, stone vessels, and a second elaborately decorated palette (now in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford) known as the Two Dogs Palette.

Conventions that remain the same for thousands of years

There are several reasons the Narmer Palette is considered to be of such importance. First, it is one of very few such palettes discovered in a controlled excavation, which means that we know it is authentic. Second, there are a number of formal and iconographic characteristics appearing on the Narmer Palette that remain conventional in Egyptian two-dimensional art for the following three millennia. These include the way the figures are represented, the scenes being organized in regular horizontal zones known as registers, and the use of hierarchical scale to indicate relative importance of the individuals. In addition, much of the regalia worn by the king, such as the crowns, kilts, royal beard, and bull tail, as well as other visual elements, including the pose Narmer takes on one of the faces where he grasps an enemy by the hair and prepares to smash his skull with a mace, continue to be utilized from this time all the way through the Roman era more than 3000 years later.

What we see on the palette

The king is represented twice in human form, once on each face, followed by his sandal-bearer. He may also be represented as a powerful bull, destroying a walled city with his massive horns, in a mode that again becomes conventional—pharaoh is regularly referred to as “Strong Bull” in later texts.

In addition to the primary scenes, the palette includes a pair of fantastic creatures, known as serpopards—leopards with long, snaky necks—who are collared and controlled by a pair of attendants. Their necks entwine and define the recess where the makeup preparation took place. The lowest register on both sides include images of dead foes, while both uppermost registers display hybrid human-bull heads and the name of the king. The frontal bull heads are connected to a sky goddess known as Bat and are related to heaven and the horizon. The name of the king, written hieroglyphically as a catfish and a chisel, is contained within a squared element that represents a palace facade.

Possible interpretation: unification of Upper and Lower Egypt

As mentioned above, there have been a number of theories related to the scenes carved on this palette. Some have interpreted the battle scenes as a historical narrative record of the initial unification of Egypt under one ruler, supported by the general timing (as this is the period of the unification) and the fact that Narmer sports the crown connected to Upper Egypt on one face of the palette and the crown of Lower Egypt on the other—this is the first preserved example where both crowns are used by the same ruler. Other theories suggest that, rather than an actual historical representation, these scenes were purely ceremonial and related to the concept of unification in general.

Detail, Palette of King Narmer, from Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Predynastic, c. 3000–2920 B.C.E., slate, 2′ 1″ high (Egyptian Museum, Cairo)

Another interpretation: the sun and the king

More recent research on the decorative program has connected the imagery to the careful balance of order and chaos (known as ma’at and isfet) that was a fundamental element of the Egyptian idea of the cosmos. It may also be related to the daily journey of the sun god that became a central aspect in the Egyptian religion in the subsequent centuries.

Detail, Palette of King Narmer, from Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Predynastic, c. 3000–2920 B.C.E., slate, 2′ 1″ high (Egyptian Museum, Cairo)

The scene showing Narmer wearing the Lower Egyptian Red Crown* (with its distinctive curl) depicts him processing towards the decapitated bodies of his foes. The two rows of prone bodies are placed below an image of a high-prowed boat preparing to pass through an open gate. This may be an early reference to the journey of the sun god in his boat. In later texts, the Red Crown is connected with bloody battles fought by the sun god just before the rosy-fingered dawn on his daily journey and this scene may well be related to this. It is interesting to note that the foes are shown as not only executed, but rendered completely impotent—their castrated penises have been placed atop their severed heads.

On the other face, Narmer wears the Upper Egyptian White Crown* (which looks rather like a bowling pin) as he grasps an inert foe by the hair and prepares to crush his skull with a mace. The White Crown is related to the dazzling brilliance of the full midday sun at its zenith as well as the luminous nocturnal light of the stars and moon. By wearing both crowns, Narmer may not only be ceremonially expressing his dominance over the unified Egypt, but also the early importance of the solar cycle and the king’s role in this daily process.

This fascinating object is an incredible example of early Egyptian art. The imagery preserved on this palette provides a peek ahead to the richness of both the visual aspects and religious concepts that develop in the ensuing periods. It is a vitally important artifact of extreme significance for our understanding of the development of Egyptian culture on multiple levels.

*The Red Crown of Lower Egypt and the White Crown of Upper Egypt were the earliest crowns worn by the king and are closely connected with the unification of the country that sparks full-blown Egyptian civilization. The earliest representation of them being worn by the same ruler is on the Narmer Palette, signifying that the king was ruling over both areas of the country. Soon after the unification, the fifth ruler of the First Dynasty is shown wearing the two crowns simultaneously, combined into one. This crown, often referred to as the Double Crown, remains a primary crown worn by pharaoh throughout Egyptian history. The separate Red and White crowns, however, continue to be worn as well and retain their geographic connections. There are a number of Egyptian words used for these crowns (nine for the White and 11 for the Red), but the most common—deshret and hedjet—refer to the colors red and white, respectively. It is from these identifying terms that we take their modern name. Early texts make it clear that these crowns were believed to be imbued with divine power and were personified as goddesses.

An Introduction to Hieroglyphs

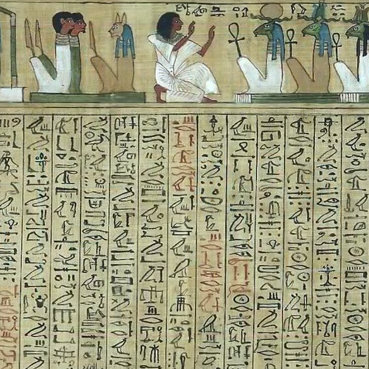

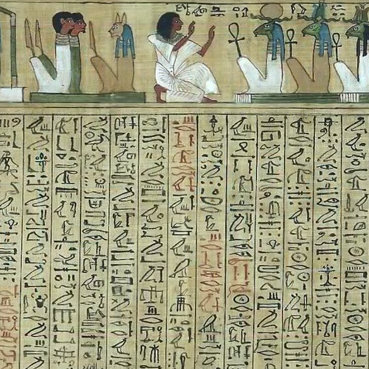

Hunefer’s Judgement in the presence of Osiris, Book of the Dead of Hunefer, 19th Dynasty, New Kingdom, c. 1275 B.C.E., papyrus, Thebes, Egypt (British Museum)

It is not known exactly where and when Egyptian writing first began, but it was already well-advanced two centuries before the start of the First Dynasty that suggests a date for its invention in Egypt around 3,000 B.C.E. The most well-known script used for writing the Egyptian language was in the form of a series of small signs, or hieroglyphs.

Some signs are pictures of real-world objects, while others are representations of spoken sounds. These sound signs are pictures that get their meaning from how the word for the object they represent sounds when said aloud. Some signs write one letter, some more, while others write whole words.

Like cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs were used for record-keeping, but also for monumental display dedicated to royalty and deities. The word hieroglyph comes from the Greek hieros ‘sacred’ and gluptien ‘carved in stone’. The last known hieroglyph inscription was 394 C.E.

Other scripts used to write Egyptian were developed over time. Hieratic was handwritten and easier to write so was used for administrative and non-monumental texts from the Old Kingdom (about 2613–2160 B.C.E.) to around 700 B.C.E. Hieratic was replaced by demotic, which means popular, in the Late Period (661–332 B.C.E.), and was a more abbreviated version. In turn demotic was replaced by Coptic, which may have been introduced to record the contemporary spoken language, in the first century C.E.

King Den’s sandal label, c. 2985 B.C.E., Early Dynastic Period, 1st dynasty, ivory, found at Abydos, Upper Egypt, 4.5 x 5.3 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Labels

Most ivory plaques dating to the First Dynasty were made as labels. The pair of sandals incised on the back of this one indicates that it was a label for sandals, which were extremely prestigious items.

Labels such as these were usually decorated with representations of important events and this example shows Den, the fifth king of the First Dynasty, about to bring his mace down on the head of his vanquished enemy. The name of the king is written in the rectangular frame in front of his face, with the figure of a falcon, a symbol of royalty, above. The hieroglyphs behind the king give the name of one of his high officials, Inka.

This label is one of the few sources for information about activity inside or outside Egypt in the Early Dynastic period. The hieroglyphs on the right-hand side of the label read ‘first occasion of smiting the East’. That the enemy is an Easterner is indicated by his long locks and pointed beard. The gravel-spotted desert which serves as a ground-line rises to a hill on the right, suggestive of Egyptian depictions of foreign lands.

Such illustrations are a standard way of depicting kings and do not necessarily mean that any such campaign ever took place. Kings are shown, over a period of 2,000 years, smiting Libyan chiefs—some with the same name! However, all standard motifs must have a prototype, and, being one of the earliest known, this example might refer to a real historical event.

Two scribal palettes with ink wells and brushes, 18th Dynasty, 1550–1450 B.C.E., ivory, from Thebes, Egypt, 30.5 x 3.8 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Written in black and red

The hieroglyphic sign for ‘write’ was formed from an image of the scribal palette and brush case. Statues of scribes are sometimes shown with a papyrus across their knees and a palette, the scribe’s trademark, over one shoulder.

From the late Old Kingdom on, the basic palette was made of a rectangular piece of wood, with two cavities at one end to hold cakes of black and red ink. Carbon was used to make the black ink and iron-rich red ochre to make the red. Both pigments were mixed with gum so that they congealed rather than turned to dust when they dried. The cakes of ink were moistened with a wet brush, rather like modern watercolors or Chinese ink. Brush-pens were made of rushes, the tip cut at an angle and chewed to separate the fibers. These were kept in a slot in the middle of the palette.

Black was the normal color for writing. Red was used to mark the start of a text, or to highlight key words and phrases, like quantities in medicines, or for the names of demons in religious papyri. More colors were needed for illustrations, such as those in the Book of the Dead.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Additional resources:

Brovarski and others (eds), Egypts golden age: the art of living in the New Kingdom (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1982)

E.R. Russmann, Eternal Egypt: masterworks of ancient art from the British Museum (University of California Press, 2001)

Parkinson, Cracking codes: the Rosetta Stone and Decipherment (London, The British Museum Press, 1999)

Quirke and A.J. Spencer, The British Museum book of ancient Egypt (London, The British Museum Press, 1992)