Ceramics

Bucchero, a distinctly black, burnished ceramic ware, is often considered the signature ceramic fabric of the Etruscans, an indigenous, pre-Roman people of the Italian peninsula. The term bucchero derives from the Spanish term búcaro (Portuguese: pucaro), meaning either a ceramic jar or a type of aromatic clay. The main period of bucchero production and use stretches from the seventh to the fifth centuries B.C.E. A tableware made mostly for elite consumption, bucchero pottery occupies a key position in our understanding of Etruscan material culture.

Manufacture

Bucchero’s distinctive black color results from its manufacturing process. The pottery is fired in a reducing atmosphere, meaning the amount of oxygen in the kiln’s firing chamber is restricted, resulting in the dark color. The oxygen-starved atmosphere of the kiln causes the iron oxide in the clay to give up its oxygen molecules, making the pottery darken in color. The fact that pottery was burnished (polished by rubbing) before firing creates the high, almost metallic, sheen. This lustrous, black finish is a hallmark of bucchero pottery. Another hallmark is the fine surface of the pottery, which results from the finely levigated (ground) clay used to make bucchero.

Terracotta column-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water), c. 560–500 B.C.E., Etruscan, terracotta, bucchero pesante, 16 1/8 in high, 13 9/16 in diameter (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Bucchero wares may draw their inspiration from metalware vessels, particularly those crafted of silver, that would have been used as elite tablewares. The design of early bucchero ware seems to evoke the lines and crispness of metallic vessels; additionally early decorative patterns that rely on incision and rouletting (roller-stamping) also evoke metalliform design tendencies.

Forerunners of Etruscan bucchero

Terracotta kyathos (single-handled cup), 7th century B.C.E., Late Villanova, terracotta, buccheroid impasto, 4 9/16 in high without handle, 8 11/16 in with handle, 11 in diameter of mouth (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Impasto (a rough unrefined clay) ceramics produced by the Villanovan culture (the earliest Iron Age culture of central and northern Italy) were forerunners of Etruscan bucchero forms. Also called buccheroid impasto, they were the product of a kiln environment that allows for a preliminary phase of oxidation but then only a partial reduction, yielding a surface finish that ranges from dark brown to black, but with a section that remains fairly light in color. The kyathos in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (above) provides a good example; the quality of potting is high overall. This impasto ware was thrown on the wheel, has a highly burnished surface, but has a less refined fabric (material) than later examples of true bucchero.

Bucchero types

Archaeologists have discovered bucchero in Etruria and Latium (modern Tuscany and northern Lazio) in central Italy; it is often frequently found in funereal contexts. Bucchero was also exported, in some cases, as examples have been found in southern France, the Aegean, North Africa, and Egypt.

Terracotta trefoil oinochoe (jug), c. 625–600 B.C.E., Etruscan, terracotta, bucchero sottile, 11 3/16 in high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The production of bucchero is typically divided into three artistic phases. These are distinguishable on the basis of the quality and thickness of the fabric. The phases are: “thin-walled bucchero” (bucchero sottile), produced c. 675 to 626 B.C.E., “transitional,” produced c. 625 to 575 B.C.E., and “heavy bucchero” (bucchero pesante), produced from c. 575 to the beginning of the fifth century B.C.E.

Terracotta kantharos (drinking cup), c. 650–600 B.C.E., Etruscan, terracotta, bucchero sottile, 12 in high without handles, 10 1/4 in diameter (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The earliest bucchero has been discovered in tombs at Caere (just northwest of Rome). Its extremely thin-walled construction and sharp features echo metallic prototypes. Decoration on the earliest examples is usually in the form of geometric incision, including chevrons and other linear motifs (above). Roller stamp methods would later replace the incision.

Bucchero hydria (water ware jug), c. 550–500 B.C.E., Etruscan, terracotta, 60.5 cm high © The Trustees of the British Museum

By the sixth century B.C.E., a “heavy” type of the ceramic had replaced the thin-walled bucchero. A hydria (vessel used to carry water) in the British Museum (above) is another example of the “heavy” bucchero of the sixth century B.C.E. This vessel has a series of female appliqué heads as well as other ornamentation. A tendency of the “heavy” type also included the use of mold-made techniques to create relief decoration.

A number of surviving bucchero examples carry incised inscriptions. A bucchero vessel currently in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (above) provides an example of an abecedarium (the letters of the alphabet) inscribed on a ceramic vessel. This vase, in the form of a cockerel, dates to the second half of the seventh century B.C.E. has the 26 letters of the Etruscan alphabet inscribed around its belly (below)—the vase combines practicality (it may have been used as an inkwell) with a touch of whimsy. It demonstrates the penchant of Etruscan potters for incision and the plastic modeling of ceramic forms.

Alphabet (detail), Terracotta vase in the shape of a cockerel, c. 650–600 B.C.E., Etruscan, terracotta, bucchero, 4 1/16 in high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Interpretation

Bucchero pottery represents a key source of information about the Etruscan civilization. Used by elites at banquets, bucchero demonstrates the tendencies of elite consumption among the Etruscans. The elite display at the banqueting table helped to reinforce social rank and to allow elites to advertise the achievements and status of themselves and their families.

Additional Resources:

Bucchero at the British Museum

Jon M. Berkin, The Orientalizing Bucchero from the Lower Building at Poggio Civitate (Murlo) (Boston: Published for the Archaeological Institute of America by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2003).

Mauro Cristofani, Le tombe da Monte Michele nel Museo archeologico di Firenze (Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1969).

Richard DePuma, Corpus vasorum antiquorum. [United States of America]. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu: Etruscan Impasto and Bucchero (Corpus vasorum antiquorum., United States of America, fasc. 31: fascim. 6.) (Malibu: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1996).

Richard DePuma, Etruscan Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013).

Nancy Hirschland-Ramage, “Studies in Early Etruscan Bucchero,” Papers of the British School at Rome 38 (1970), pp. 1–61.

Philip Perkins, Etruscan Bucchero in the British Museum (London: The British Museum, 2007).

Tom Rasmussen, Bucchero Pottery from Southern Etruria (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979).

Wim Regter, Imitation and Creation: Development of Early Bucchero Design at Cerveteri in the Seventh Century BC (Amsterdam: Allard Pierson Museum, 2003).

Margaret Wadsworth, “A Potter’s Experience with the Method of Firing Bucchero,” Opuscula Romana 14 (1983), pp. 65-68.

Regolini-Galassi Tomb and Parade Fibula

Three Lions (detail), Large Parade Fibula (rear chamber, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, Cerveteri), 670–650 B.C.E., gold, 29.2 cm long (Museo Gregoriano Etrusco, Musei Vaticani) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The interconnectedness of the ancient Mediterranean world

The material culture of the Mediterranean basin in the seventh century B.C.E. affords us a glimpse of a dynamic and increasingly interconnected world. This Proto-Archaic phase of the Mediterranean world (also sometimes still referred to as the “Orientalizing” period) offers evidence of techniques—and possibly even artists and makers themselves—transmitted and transported from one region to another. Funereal architecture and associated material objects deposited in tombs, often referred to as “grave goods,” provide important indications about contemporary customs, materials, and monuments and serve as revealing indicators of the priorities and preferences of a culture.

Large Parade Fibula, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, from the main tomb in the lower chamber, 675–650 B.C., gold: embossed, punched, cut, and granulated (Museo Gregoriano Etrusco, Musei Vaticani) (Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An Etruscan tomb

In 1836 an Etruscan tomb located in the Sorbo necropolis of ancient Caere (now Cerveteri, Italy) was opened and its contents revealed. The tomb was of the tumulus-type, meaning a tomb covered with a mound of earth, and was of the sort used by the members of the social elite of the Etruscan culture. The seventh-century B.C.E. tomb had remained intact and undisturbed since antiquity (a fortuitous circumstance since such tombs are frequently discovered in a disturbed or looted state).

Detail, Large Parade Fibula, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, from the main tomb in the lower chamber, 675–650 B.C., gold: embossed, punched, cut and granulated (Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The funereal objects (now in the Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums), demonstrate how objects and materials can communicate messages about a person’s social or economic status. The the assemblage of objects in the Regolini-Galassi tomb represents a broad geographic range and an aesthetic that indicates the influence of the ancient Near East. This is especially evident in metal-working techniques used to produce objects in the tomb and, in the broader landscape of funereal culture, objects either imported from the Near East or manufactured by Near Eastern craftspeople for elite consumption (such as their use as grave goods). Social elites not only desired to own and display such objects but also used them to reinforce their status and that of their family. The conspicuous deposition of these objects in the tomb would indicate to viewers or onlookers that not only was the deceased an important person but also that her surviving family members were important people in the community. In this way, the objects themselves facilitate a conversation about wealth and status among the Etruscans.

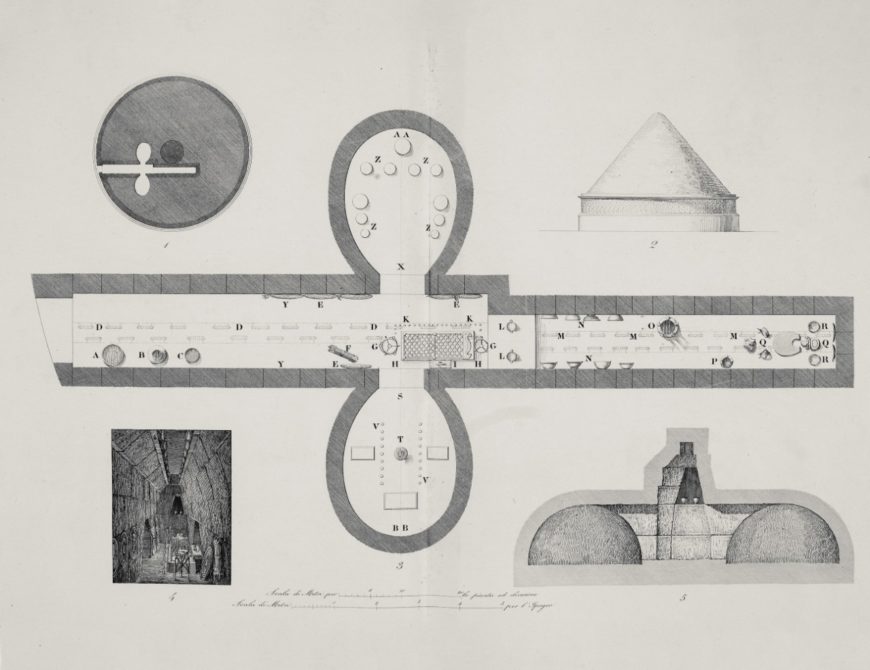

Corbelled vault, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, Cerveteri

The architecture of the tomb and its context

The explorers of the tomb—General Vincenzo Galassi, a military officer, and Alessandro Regolini, the archpriest of Cerveteri—discovered that the tomb’s primary occupant was an adult female and that, judging both by the tomb architecture and the grave goods, she would have numbered among the social elite of ancient Caere.

The tomb is monumental in scale and was partially carved from the tuff bedrock of Caere. The tomb is approached by a short, narrow dromos and is composed of a 37-meter long corridor off of which two side chambers open. A corbelled vault covers the dromos. The exterior of the tomb was covered by an initial mound of earth known as a tumulus that measured some 46 meters in diameter; a second tumulus covered the tomb in the sixth century B.C.E. when additional tombs were added.

Once built, the tomb was stocked with grave goods to accompany the descendants; no fewer than 327 objects have been recorded. Many of these objects were manufactured of precious metals, including a significant quantity of gold. The tomb’s side chambers were used, respectively, for storage and the burial of a cremated male. The closed chamber at the end of the lateral corridor contained the principal burial, that of an elite female, and the majority of the grave goods (no. 1 to 226 in Pareti’s documentation). Some of the grave objects are inscribed mi larthia, meaning “I am the property of Larth.” This suggests that Larth, being a male, is the father of the deceased woman. Additional epigraphic evidence has led to the identification of the woman herself as one Larthia Velthurus. The parade fibula was found associated with this female burial, although precise documentation of the findspot is unclear since the tomb’s opening predates modern archaeology. The conventional date for the tomb and its contents is c. 675 to 650 B.C.E., although some scholars will move the date forward to the 640s B.C.E.

The so-called Parade Fibula and its design

The so-called parade fibula itself measures 31.5 cm high by 24.4 cm thick; the disc ranges in thickness from 0.11 to 0.19 mm. The fibula weighs 173 grams (6.1024 ounces). While a normal-sized fibula would have functioned as a pin to fasten garments together (much like a modern safety pin operates), the functionality of this example, given its size and splendor, has long been debated. It is possible that this example was prepared especially as a grave offering for the deceased female.

Scholars have debated the function of the parade fibula since the tomb’s discovery. Various theories have been proposed, including that the fibula could have been displayed as a sort of headdress (and so not a fibula at all?), including one that imagines it positioned atop the face and forehead of the decedent. Most interpretations pair the fibula with the so-called gold pectoral from the same tomb that similarly demonstrates the influence of Near Eastern metal-working techniques and geometric patterns.

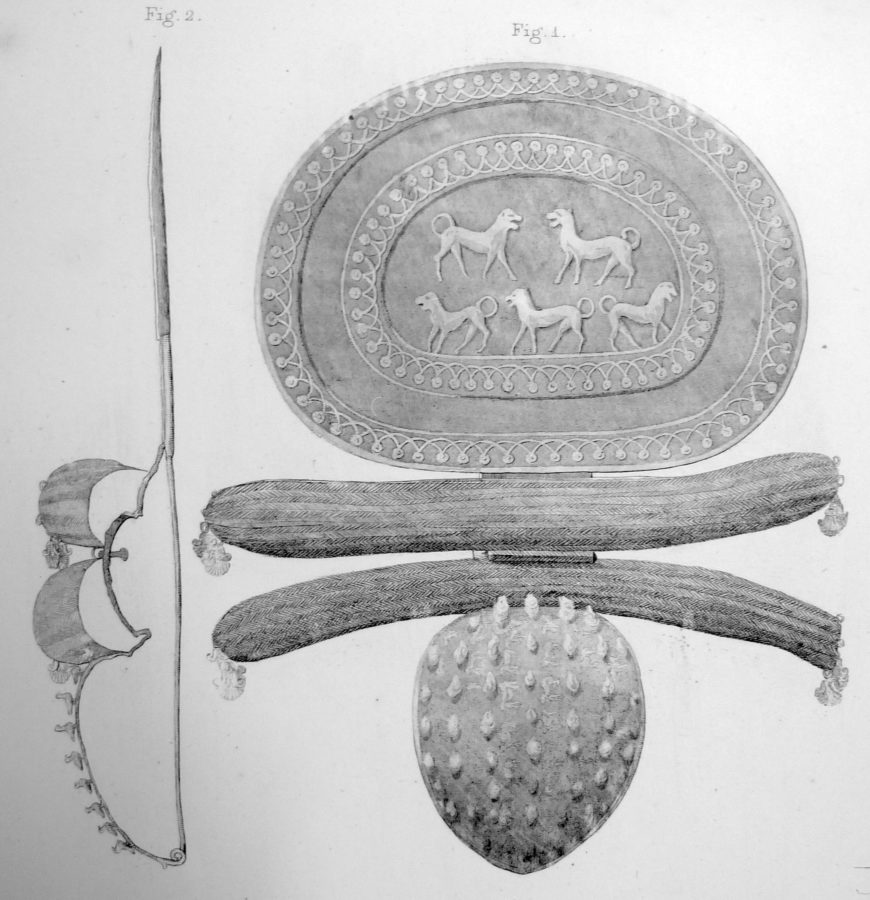

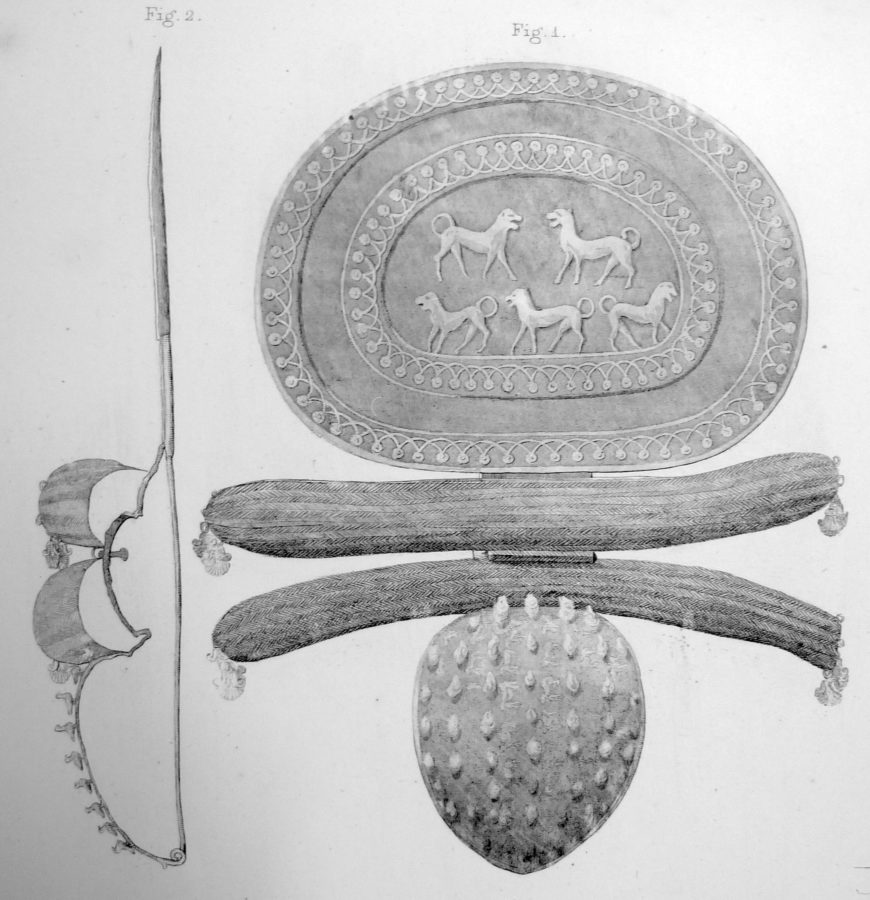

Profile (left) and front view (right) of the Regolini-Galassi disc fibula by Luigi Canina (1846)

Three elements make up the so-called parade fibula. These are, from bottom to top, an oval-shaped, arched element, a flat semi-circular disc, and a pair of transverse, hollow cylinders that are attached to the other elements by a hinge. A long pin is attached to the back of the fibula.

Decorative techniques

Detail, Large Parade Fibula, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, from the main tomb in the lower chamber, 675-650 B.C., gold: embossed, punched, cut and granulated (Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Fibula decorated with zigzag lines and incised labyrinths (Proto-Etruscan), c. 825–775 B.C.E., gold, 7.4 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

The techniques that were used to decorate the surface of the fibula are indicative of artistic trends and technologies originating in the ancient Near East that were overspreading the Mediterranean basin. These techniques—granulation, filigree, and repoussé —all originated in the east, with granulation appearing in tombs at Ur in Mesopotamia by c. 2500 B.C.E. The granulation technique is attested in Etruria beginning in the middle of the eighth century B.C.E.

The decorative motifs that reference the afterlife, including the presence of the Egyptian goddess Hathor seem to confirm the fibula’s funeral function. Hathor is visible on the terminus of the lower element of the fibula. Although the Regolini-Galassi parade fibula is unique, it finds comparison with other contemporary disc fibulae such as the one in the collection of The British Museum.

Five lions (detail), Large Parade Fibula, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, from the main tomb in the lower chamber, 675-650 B.C., gold: embossed, punched, cut and granulated (Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A group of five lions occupies the center of the semicircular disc of the fibula. These lions were made by the use of stamps and then attached to the disc of the fibula. A border achieved with the granulation technique frames the lions. The surface of the horizontal tubular elements are covered with granulation, while the lower ovoid element includes patterns like a frieze of griffins that indicates the influence of the ancient Near East. The composition of the iconography of the fibula stresses elite themes and status, since an item of foreign manufacture that reinforces royal icons reinforces the status and activities of social elites and the behaviors they used to maintain their position. Ritual themes are important as well and, overall, the group of grave goods represents the outlook of Mediterranean social elites of the Proto-Archaic period.

Frieze of griffins (detail), Large Parade Fibula, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, from the main tomb in the lower chamber, 675-650 B.C., gold: embossed, punched, cut and granulated (Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A world increasingly connected

The iconographic motifs (the griffins and lions) of the parade fibula speaks to the influence of the ancient Near East and possibly even to manufacture by artisans from Syro-Palestine.

Taken as part of the larger assemblage of artifacts, the fibula speaks volumes about the needs of Etruscan elites in the seventh century B.C.E. These elites felt it necessary to communicate and reinforce their own socio-economic status by accumulating and displaying certain types of objects that matched their apparent status. Not only were many of these objects crafted from intrinsically valuable materials like gold they also had the appeal of being examples of imported and exotic items. Similar items likely were to be found in the homes and tombs of the social peers of the occupants of the Regolini-Galassi tomb, as proto-archaic elites jockeyed for position and used objects and materials acquired by means of long-distance supply chains to signal their primacy and relevance in a world that was increasingly interlinked and moving ever more quickly.

Additional resources

Large Parade Fibula, Musei Vaticani, Large parade Fibula (Vatican Museum)

Etruscanning: digital encounters with the Regolini-Galassi Tomb with blog posts.

Massimo Botto and Alessandro Naso, eds. Caere orientalizzante: nuove ricerche su città e necropoli (Studia Caeretana; 1) (Rome: CNR, Istituto di studi sul Mediterraneo antico; Paris: Musée du Louvre, Département des antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines, 2018).

Francesco Buranelli and Maurizio Sannibale, “Non piu solo ‘Larthia’. Un documento epigrafico inedito dalla Tomba Regolini-Galassi di Caere,” in Aei mnestos: miscellanea i studi per Mauro Cristofani, edited by B. Adembri (Florence: Centro Di, 2005) pp. 220-31..

Richard Daniel De Puma, “Ch. 18. Gold and Ivory,” in Caere, edited by Nancy Thomson de Grummond and Lisa C. Pieraccini (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016), pp. 195–208.

Adriana Emiliozzi, “La tomba Regolini-Galassi e i suoi carri.” in Caere orientalizzante: nuove ricerche su città e necropoli, edited by Alessandro Naso and Massimo Botto (Rome; Paris: CNR Istituto di studi sul Mediterraneo antico, 2018), pp. 195–304.

F. W. v. Hase, “The ceremonial jewellery from the Regolini-Galassi tomb in Cerveteri: Some ideas concerning the workshop,” in Prehistoric Gold in Europe: Mines, Metallurgy and Manufacture, edited by Giulio Morteani and Jeremy P. Northover (Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995) pp. 533–559.

Tamar Hodos, The Archaeology of the Mediterranean Iron Age: A Globalising World c.1100–600 B.C.E. (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Luigi Pareti, La tomba Regolini-Galassi del Museo gregoriano etrusco e la civiltà dell’Italia centrale nel sec. VII a.C. (Vatican City: Tip. poliglotta vaticana, 1947).

Elfriede Paschinger, “Über ein mögliches familiäres Verhältnis der in der Tomba Regolini — Galassi bestatteten Personen,” Antike Welt, vol. 24, no. 2 (1993), pp. 111–124

Ingrid Pohl, The Iron Age Necropolis of Sorbo at Cerveteri (Skrifter utgivna av Svenska Institutet i Rom; 4,32.) (Stockholm: Svenska Institutet i Rom, 1972).

Christie A. Ray, “Natural interaction in VR environments for cultural heritage: the virtual reconstruction of the Regolini-Galassi tomb in Cerveteri,” in Archeologia e calcolatori 24 (2013) pp. 231-247.

Christie A. Ray, J. Vos, and P. Retèl, Etruscanning: Digital Encounters with the Regolini-Galassi Tomb (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum, 2013).

Laura Maria Russo, “Dalla Tomba Regolini Galassi alle hydrie ceretane: il ruolo di Cerveteri nell’assimilazione del bestiario fantastico orientalizzante in Etruria,” in Nuovi studi sul bestiario fantastico di età orientalizzante nella penisola italiana (Trento: Tangram Edizioni Scientifiche, 2015) pp. 275–302.

Maurizio Sannibale, “Gli ori della Tomba Regolini-Galassi: tra tecnologia e simbolo. Nuove proposte di lettura nel quadro del fenomeno orientalizzante in Etruria.” Mélanges de l’École Française de Rome 120,2 (2008) pp. 337–367.

Maurizio Sannibale, “Iconografie e simboli orientali nelle corti dei principi etruschi,” Byrsa 7, 1 / 2 (2008), pp. 85–123.

Maurizio Sannibale, “Orientalizing Etruria,” in The Etruscan World, edited by Jean MacIntosh Turfa (London: Routledge, 2014). pp. 99–133.

Jean MacIntosh Turfa, “Ch. 3. International contacts: commerce, trade, and foreign affairs,” Etruscan life and afterlife: a handbook of Etruscan studies, edited by Larissa Bonfante (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1986) pp. 66–91.

Temple of Minerva and the sculpture of Apulu (Apollo of Veii)

Forget what you know about Greek and Roman architectural orders—Etruscans had their own unique style.

Apulu (Apollo of Veii), from the roof of the Portonaccio temple, Italy, c. 510–500 B.C.E., painted terracotta, 5′ 11″ high (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome)

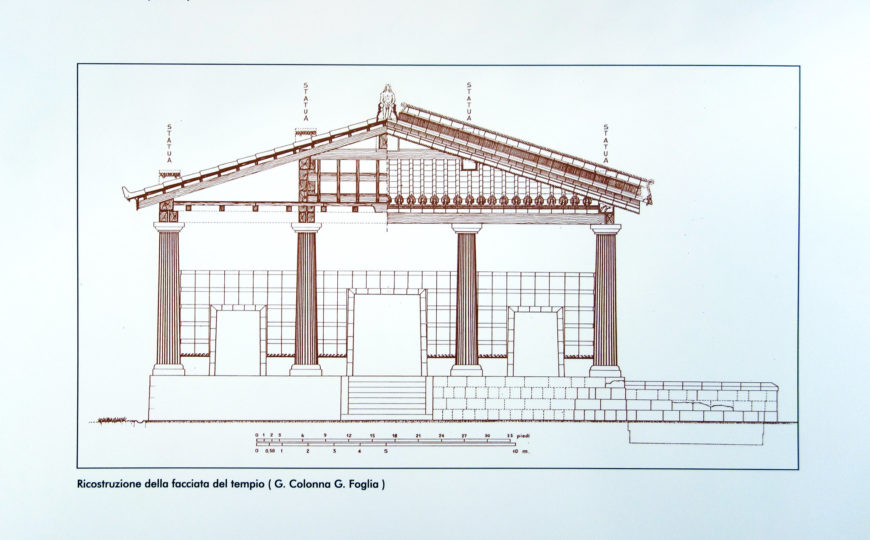

Reconstruction of an Etruscan Temple of the 6th century according to Vitruvius (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Etruscan temples have largely vanished

Among the early Etruscans, the worship of the Gods and Goddesses did not take place in or around monumental temples as it did in early Greece or in the Ancient Near East, but rather, in nature. Early Etruscans created ritual spaces in groves and enclosures open to the sky with sacred boundaries carefully marked through ritual ceremony.

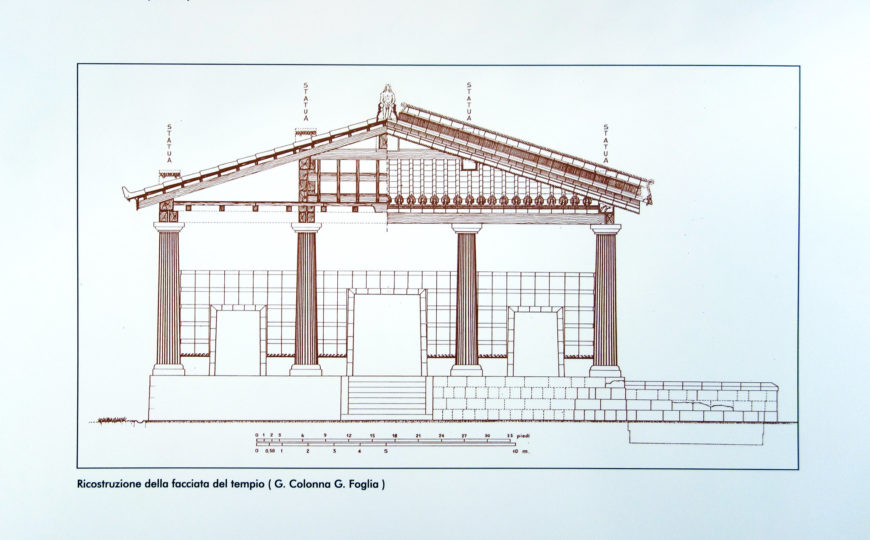

Around 600 B.C.E., however, the desire to create monumental structures for the gods spread throughout Etruria, most likely as a result of Greek influence. While the desire to create temples for the gods may have been inspired by contact with Greek culture, Etruscan religious architecture was markedly different in material and design. These colorful and ornate structures typically had stone foundations but their wood, mud-brick and terracotta superstructures suffered far more from exposure to the elements. Greek temples still survive today in parts of Greece and southern Italy since they were constructed of stone and marble but Etruscan temples were built with mostly ephemeral materials and have largely vanished.

How do we know what they looked like?

Despite the comparatively short-lived nature of Etruscan religious structures, Etruscan temple design had a huge impact on Renaissance architecture and one can see echoes of Etruscan, or ‘Tuscan,’ columns (doric columns with bases) in many buildings of the Renaissance and later in Italy. But if the temples weren’t around during the 15th and 16th centuries, how did Renaissance builders know what they looked like and, for that matter, how do we know what they looked like?

Fortunately, an ancient Roman architect by the name of Vitruvius wrote about Etruscan temples in his book De architectura in the late first century B.C.E. In his treatise on ancient architecture, Vitruvius described the key elements of Etruscan temples and it was his description that inspired Renaissance architects to return to the roots of Tuscan design and allows archaeologists and art historians today to recreate the appearance of these buildings.

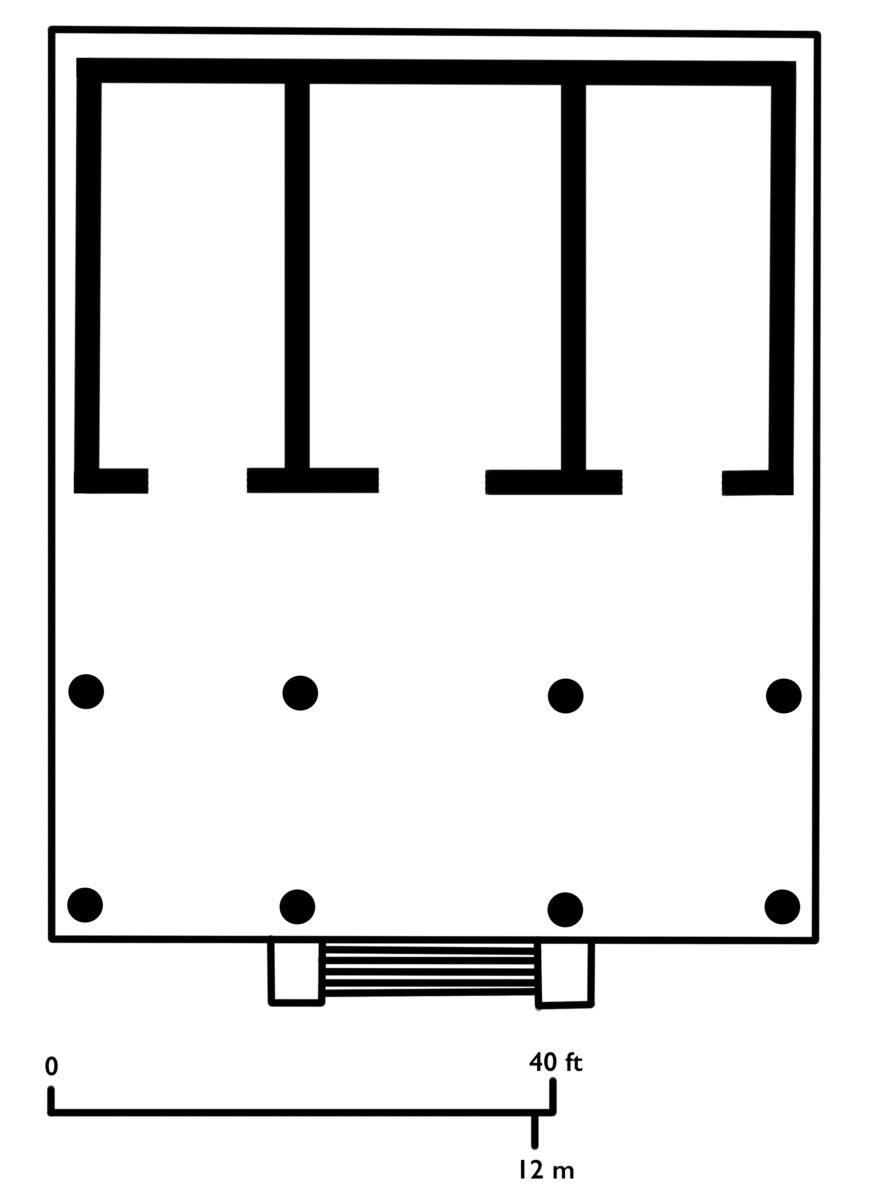

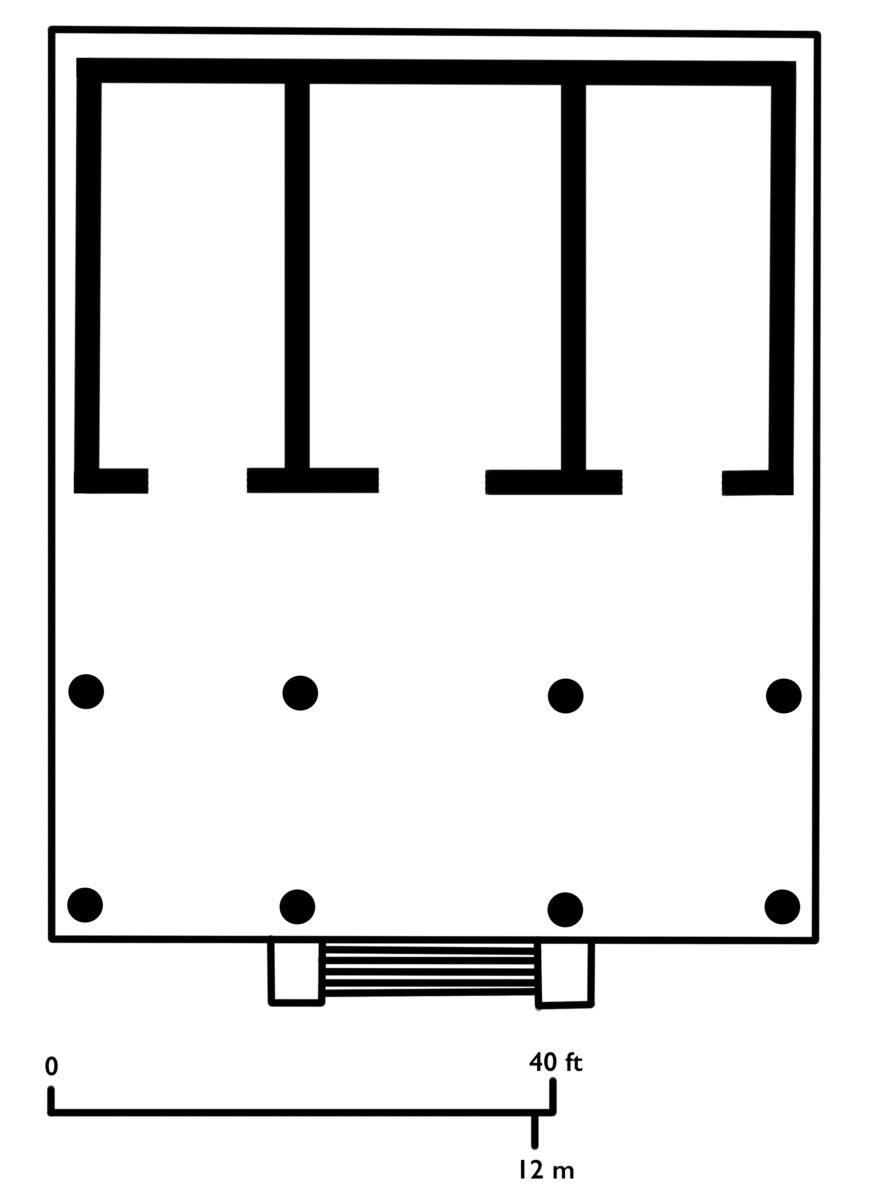

Typical Etruscan temple plan

Archaeological evidence for the Temple of Minerva

The archaeological evidence that does remain from many Etruscan temples largely confirms Vitruvius’s description. One of the best explored and known of these is the Portonaccio Temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva (Roman=Minerva/Greek=Athena) at the city of Veii about 18 km north of Rome. The tufa-block foundations of the Portonaccio temple still remain and their nearly square footprint reflects Vitruvius’s description of a floor plan with proportions that are 5:6, just a bit deeper than wide.

The temple is also roughly divided into two parts—a deep front porch with widely-spaced Tuscan columns and a back portion divided into three separate rooms. Known as a triple cella, this three room configuration seems to reflect a divine triad associated with the temple, perhaps Menrva as well as Tinia (Jupiter/Zeus) and Uni (Juno/Hera).

In addition to their internal organization and materials, what also made Etruscan temples noticeably distinct from Greek ones was a high podium and frontal entrance. Approaching the Parthenon with its low rising stepped entrance and encircling forest of columns would have been a very different experience from approaching an Etruscan temple high off the ground with a single, defined entrance.

Reconstruction of an Etruscan Temple of the 6th century according to Vitruvius identifying placement of terracotta sculpture (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Sculpture

Perhaps most interesting about the Portonaccio temple is the abundant terracotta sculpture that still remains, the volume and quality of which is without parallel in Etruria. In addition to many terracotta architectural elements (masks, antefixes, decorative details), a series of over life-size terracotta sculptures have also been discovered in association with the temple. Originally placed on the ridge of temple roof, these figures seem to be Etruscan assimilations of Greek gods, set up as a tableau to enact some mythic event.

Detail, Aplu (Apollo of Veii), from the roof of the Portonaccio Temple, Veii, Italy, c. 510–500 B.C.E., painted terracotta, 5 feet 11 inches high (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Aplu (Apollo of Veii), from the roof of the Portonaccio Temple, Veii, Italy, c. 510–500 B.C.E., painted terracotta, 5 feet 11 inches high (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Apollo of Veii

The most famous and well-preserved of these is the Aplu (Apollo of Veii), a dynamic, striding masterpiece of large scale terracotta sculpture and likely a central figure in the rooftop narrative. His counterpart may have been the less well-preserved figure of Hercle (Hercules) with whom he struggled in an epic contest over the Golden Hind, an enormous deer sacred to Apollo’s twin sister Artemis. Other figures discovered with these suggest an audience watching the action. Whatever the myth may have been, it was a completely Etruscan innovation to use sculpture in this way, placed at the peak of the temple roof—creating what must have been an impressive tableau against the backdrop of the sky.

An artist by the name of Vulca?

Since Etruscan art is almost entirely anonymous it is impossible to know who may have contributed to such innovative display strategies. We may, however, know the name of the artist associated with the workshop that produced the terracotta sculpture. Centuries after these pieces were created, the Roman writer Pliny recorded that in the late 6th century B.C.E., an Etruscan artist by the name of Vulca was summoned from Veii to Rome to decorate the most important temple there, the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. The technical knowledge required to produce terracotta sculpture at such a large scale was considerable and it may just have been the master sculptor Vulca whose skill at the Portonaccio temple earned him not only a prestigious commission in Rome but a place in the history books as well.

Additional resources

This sculpture at the Villa Guila, Rome

Apollo de Veio and its 2004 restoration

Etruscan art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Mars of Todi

Lightning struck this statue dedicated to the Etruscan god of war, marking it as a particularly sacred object.

Mars of Todi, late 5th or early 4th century B.C.E., hollow-cast bronze, 141 cm high (Gregorian Etruscan Museum, Vatican Museums)

The religious sanctuaries of ancient Italy were busy and multi-faceted places, playing roles not only in religion and ritual, but also in commerce and connectivity. People visited sanctuaries to participate in ritual, connect with their community, and to commune with the gods. The religions of ancient Italy relied heavily on votive practices—that is the giving of gifts or offerings to the divinities that helped to affirm a pact or agreement between the worshipper and a god or goddess. Votives could be humble objects from everyday life, or they could be purpose-made prestige objects. In all cases, votives are particularly instructive in informing us about ritual practice in the ancient world.

The statue

The so-called Mars of Todi is an inscribed Etruscan bronze statue dating to the late fifth or early fourth century B.C.E. It was discovered in 1835 on the slopes of Mount Santo near Todi, Italy (ancient Tuder). The hollow-cast bronze statue is the product of an Etruscan workshop but was likely produced for the market in Umbria (a region in central Italy).

The statue measures 141 cm in height, making it nearly life-sized. The Etruscans were adept metalworkers and Orvieto (Etruscan Velzna, Roman Volsinii) was particularly known for the production of bronze statues. The Romans reportedly removed 2,000 bronzes from Volsinii when they captured it in 265 B.C.E. (Pliny, Natural History 34.33). It is possible that the Mars of Todi was originally produced there.

Head (detail), Mars of Todi, end of the 5th century B.C.E., hollow-cast bronze, 141 cm high (Gregorian Etruscan Museum, Vatican Museums), photo: Nick Thompson (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The warrior is clearly a prestige object, a worthy votive dedication. It is likely that the object was dedicated to Laran, the Etruscan god of war. Dressed in intricately worked plate armor, the figure takes a contrapposto stance and indicates that the Etruscan artist was aware of the formal elements of the Classical style of sculpture. These classicizing elements indicates that the artists of Etruria are not only aware of Mediterranean stylistic conventions but also that they are comfortable enough with these stylistic trends that they can in turn adapt and apply them to local tastes and demand. Likely attached elements—including a patera (a libation bowl) held in the right hand and a spear in the left—have not survived, nor has the helmet that he wore atop his head.

The inscription

Caption (detail), Mars of Todi, end of the 5th century B.C.E., hollow-cast bronze, 141 cm high (Gregorian Etruscan Museum, Vatican Museums)

The bronze statue bears an inscription in the Umbrian language that has been written using Etruscan characters. This dedication is inscribed on the skirt that is attached to the breastplate and reads “Ahal Trutitis dunum dede” (“Ahal Trutitis gave [this as a] gift”). The dedicant—Ahal Trutitis—has a name that is Celtic in origin, which lends this dedication of an Etruscan object in an Umbrian sanctuary a particularly cosmopolitan element.

Interpretation

The Mars of Todi is a rare object in that many prestige votives of its stature have not survived from antiquity. The careful burial of this object—perhaps after it had been struck by lightning*—accounts for its survival. The composition represents the tradition of libations made by soldiers prior to battle, an opportunity for beseeching the gods for support and success in battle. The dedication of this object is also indicative of the dynamic human landscape of ancient Italy—within that human landscape sanctuaries often served as nodal points where diverse cultures came into contact with one another. This votive statue, then, tells us a great deal not only about ritual practice and iconography, but also about those who frequented sanctuaries in ancient Italy.

*Note on lightning as sacred

In ancient Italic religion lightning was sacred, as it was connected to the chief sky god, called Iuppiter (Jupiter) by the Romans and Tinia by the Etruscans. Thus on occasions when lightning struck the Earth, the spot which—or the object which—the lightning “selected” (fulgur conditum) would become even more sacred. Roman ritual doctrine considered these consecrated spots special and thus they were often marked in some way. The Puteal Libonis (also known as Puteal Scribonianum) in the Comitium of the Forum Romanum provides such an example; after a spot in the Comitium had been struck by lightning, it was marked with a puteal (a marble wellhead) (Festus 333). The Romans considered these special shrines, which often had a circular templum (a sacred, inaugurated precinct), as bidentalia (from the Latin noun bidental, bidentalis “a place struck by lightning”) and it was forbidden to tread on them. In the case of the Mars of Todi, the statue was found carefully buried in a stone-lined cist, leading to the conclusion that the statue had been struck by lightning, which caused it to fall from its podium and that it was subsequently ritually buried. The ritual burial of votive objects is a common practice in ancient Mediterranean religions, but the treatment of these bidentalia was special in its own right.

Additional resources:

This sculpture in the Gregorio Etruscan Museum (Vatican Museums)

G. Bonfante and L. Bonfante, The Etruscan Language: An Introduction, revised edition (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), p. 26.

G. J. Bradley, Ancient Umbria: State, Culture, and Identity in Central Italy from the Iron Age to the Augustan Era: State, Culture, and Identity in Central Italy from the Iron Age to the Augustan Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). p. 92.

O. J. Brendel, Etruscan Art, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995) p. 317.

D. Strong and J.M.C. Toynbee, Roman Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976, 1988), pp. 32–33.

F. Roncalli, Il Marte di Todi: bronzistica etrusca ed ispirazione classica (Rome: Tip. poliglotta Vaticana, 1973).

E. Simon, “Gods in Harmony: The Etruscan Pantheon,” in The Religion of the Etruscans, ed. by N. T. De Grummond and E. Simon, pp. 45-65 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006).

J. M. Turfa, Divining the Etruscan World: the Brontoscopic Calendar and Religious Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Chimera of Arezzo

A vicious mythic beast, the Chimera is a terrifying mix of animals—that even attacks itself.

Chimera from Arezzo, c. 400 B.C.E., bronze, 129 cm in length, (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence)

The Chimera of Arezzo is one of the best known pieces of Etruscan sculpture to survive from antiquity. Discovered near the Porta San Lorentino of Arezzo, Italy (ancient Arretium) in 1553, the statue was added to the collection of Cosimo I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany in the sixteenth century and is currently housed in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Florence.

Chimera from Arezzo, c. 400 B.C.E., bronze, 129 cm in length, (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence)

When the statue was discovered along with a collection of small bronzes, it was cleaned by Cosimo I and the artist Benvenuto Cellini; it was then displayed as part of the duke’s collection in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Giorgio Vasari (16th century artist, writer, and historian), studied the statue and declared it a bona fide antiquity.

What is a chimera?

The Chimera was a legendary, fire-breathing monster of Greek myth that hailed from Lycia (southwestern Asia Minor). The offspring of Typhon and Echidna, the Chimera ravaged the lands of Lycia until Bellerophon, a hero from Corinth, mounted on the winged horse Pegasus was able to slay it (Hesiod Theogony 319-25). Typically the Chimera is a hybrid—often shown with elements from more than one animal incorporated into the whole; most often these include a lion’s head, with a goat rising from its back, and a snaky tail.

Chimera from Arezzo, c. 400 B.C.E., bronze, 129 cm in length, (photo: E.M. Rosenbery; © Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana-Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Firenze)

The Chimera of Arezzo presents a complex composition that seems conceived for viewing in the round. The contortions of the fire-breathing beast, obviously wounded in combat, evoke emotion and interest from the viewer. Its writhing body parts invite contemplation of the movement, pose, and musculature of the figure. While the tail was restored post-discovery, enough of the original composition confirms this dynamism. The lean body also emphasizes the tension in the arched back, the extended claws, and the roaring mouth set amidst the bristling mane.

Detail of back, Chimera from Arezzo, c. 400 B.C.E., bronze, 129 cm in length, (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence)

The right foreleg (below) bears a dedicatory inscription in the Etruscan language. The inscription reads, “tinścvil” meaning “Offering belonging to Tinia” (TLE 663; Bonfante and Bonfante 2002, no. 26 p. 147). This indicates that the statue was a votive object, offered as a gift to the sky god Tinia.

Detail with inscription “tinścvil”, Chimera from Arezzo, c. 400 B.C.E., bronze, 129 cm in length, (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence)

Interpretation

The Chimera of Arezzo is a masterwork of Etruscan bronze working, demonstrating not only a high level of technical proficiency on the part of the artist (or workshop) that produced it but also clearly showing a fine-tuned awareness of the themes of Greek mythology that circulated around the Mediterranean. A. Maggiani discusses the wider Italiote context in which the statue was likely produced—pointing out iconographic comparisons from sites in Magna Graecia such as Metaponto and Kaulonia (Italiote refers to pre-Roman Greek speaking peoples of southern Italy, while Magna Graecia refer to the Greek colonies established in Southern Italy from the 8th century B.C.E. onward).

Detail with lion’s head, Chimera from Arezzo, c. 400 B.C.E., bronze, 129 cm in length, (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence)

These iconographic trends, indicative of increasing Attic (derived from the area around Athens, Greece) influence, suggests that the Chimera of Arrezo was produced by Italiote craftsmen who were influenced by the spread of Attic trends in art in the last years of the fifth century continuing through to the early fourth century B.C.E. The dedication of the statue as a votive offering to Tinia further reminds us of the wealth and sophistication of Etruscan elites who, in this case, could not only afford to commission the statue but could also afford to part with it in what may have been an ostentatious fashion.

Additional resources:

G. Bonfante & L. Bonfante, The Etruscan language: an introduction, revised edition (Manchester University Press, 2002).

L. Bonfante, “Etruscan Inscriptions and Etruscan Religion.” In The Religion of the Etruscans, edited by N.T. De Grummond and E. Simon, pp. 9–26 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006).

W. L. Brown, The Etruscan Lion (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960).

M. Cristofani, “Per una storia del collezionismo archeologico nella Toscana granducale. I. I grandi bronzi,” Prospettiva, 1979, vol. 17, pp. 4–15 .

M. Cristofani, I bronzi degli Etruschi (Novara: Istituto Geografico De Agostini, 1985).

M. Cristofani, “Chimereide,” Prospettiva vol. 61 (1991), pp. 2-5.

A. M. Gáldy, “The Chimera from Arezzo and Renaissance Etruscology,” in Common Ground: Archaeology, Art, Science, and Humanities. Proceedings of the XVIth International Congress of Classical Archaeology, Boston, August 23–26, 2003, edited by C.C. Mattusch, A.A. Donahue, and A. Brauer, pp. 111–13. (Oxford: Oxbow, 2006).

A. M. Gáldy, Cosimo I de’Medici as Collector: Antiquities and Archaeology in Sixteenth-Century Florence (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009).

M. Iozzo et al., The Chimaera of Arezzo (Florence: Edizioni Polistampa, 2009).

M. Pallottino, “Vasari e la Chimera,” Prospettiva, vol. 8 (1977), pp. 4–6.

R. Pecchioli, “Indagini radiografiche,” in La Chimera d’Arezzo, edited by F. Nicosia and M. Diana, pp. 89–93 (Florence: Il Torchio, 1992).

C. M. Stibbe, “Bellerophon and the Chimaira on a Lakonian Cup by the Boreads Painter,” in Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum, vol. 5, edited by M. True, pp. 5–12 (Occasional Papers on Antiquities, vol. 7) (Malibu: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1991).

J. M. Turfa, “Votive Offerings in Etruscan Religion,” In The Religion of the Etruscans, edited by N.T. De Grummond and E. Simon, pp. 90–115 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006).

Beth Cohen, “Chimera of Arezzo,” The American Journal of Archaeology, July 2010 (114.3).

“Chimera in Bronzo,” from the Ministero per i beni Culturali e Ambientali Soprintendenza Archeologica della Toscana Sezione Didattica (in Italian)