Introduction to the Art of Ancient Rome

Introduction to Ancient Rome

From a republic to an empire

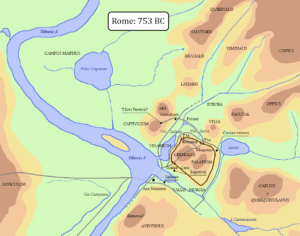

Legend has it that Rome was founded in 753 B.C.E. by Romulus, its first king. In 509 B.C.E. Rome became a republic ruled by the Senate (wealthy landowners and elders) and the Roman people. During the 450 years of the Republic, Rome conquered the rest of Italy and then expanded into France, Spain, Turkey, North Africa, and Greece.

Rome became very Greek-influenced or “Hellenized,” and the city was filled with Greek architecture, literature, statues, wall-paintings, mosaics, pottery, and glass. But with Greek culture came Greek gold, and generals and senators fought over this new wealth. The Republic collapsed in civil war and the Roman empire began.

In 31 B.C.E. Octavian, the adopted son of Julius Caesar, defeated Cleopatra and Mark Antony at Actium. This brought the last civil war of the Republic to an end. Although it was hoped by many that the Republic could be restored, it soon became clear that a new political system was forming: the emperor became the focus of the empire and its people. Although, in theory, Augustus (as Octavian became known) was only the first citizen and ruled by consent of the Senate, he was in fact the empire’s supreme authority. As emperor he could pass his powers to the heir he decreed and was a king in all but name.

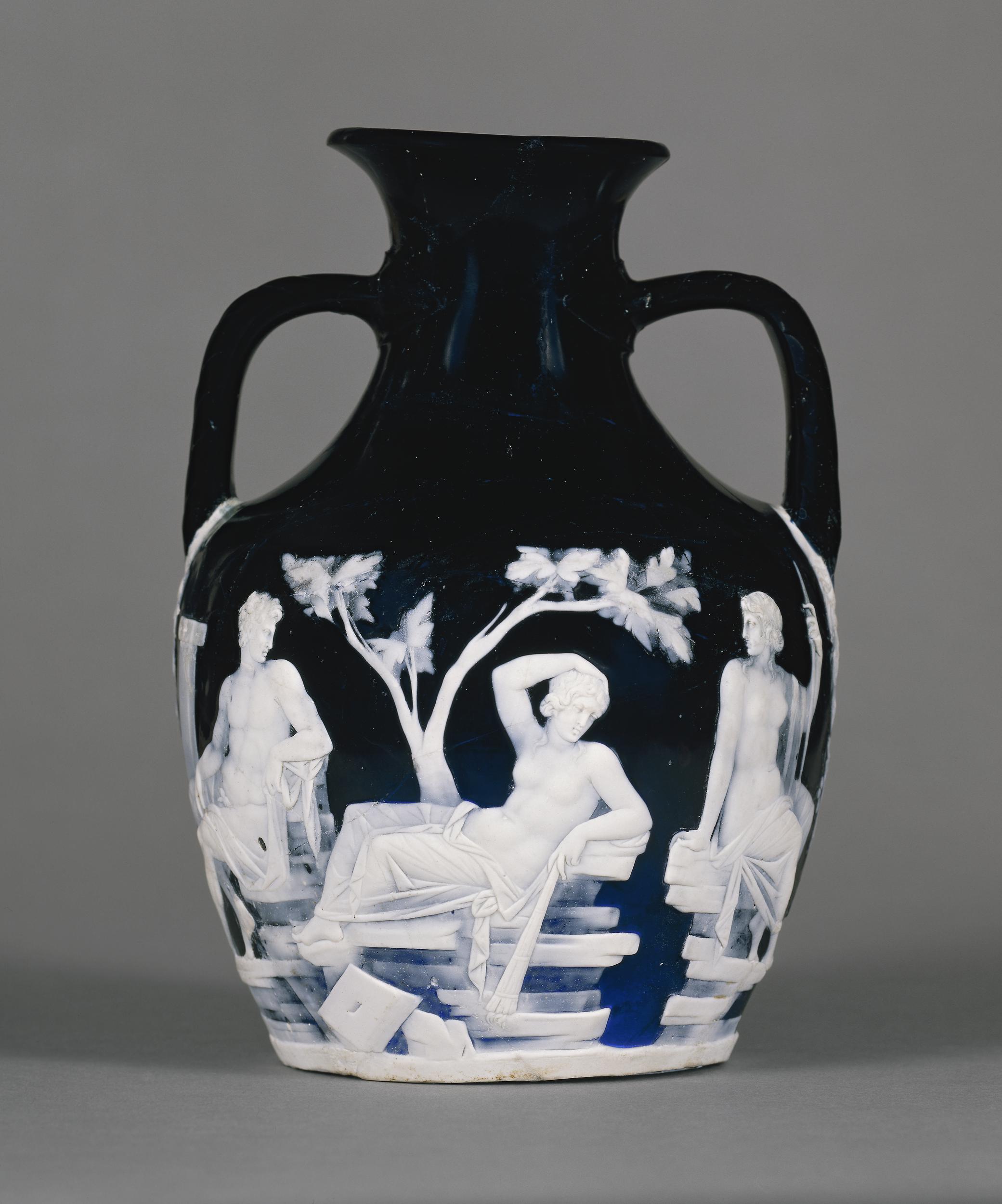

The empire, as it could now be called, enjoyed unparalleled prosperity as the network of cities boomed, and goods, people, and ideas moved freely by land and sea. Many of the masterpieces associated with Roman art, such as the mosaics and wall paintings of Pompeii, gold and silver tableware, and glass, including the Portland Vase, were created in this period. The empire ushered in an economic and social revolution that changed the face of the Roman world: service to the empire and the emperor, not just birth and social status, became the key to advancement.

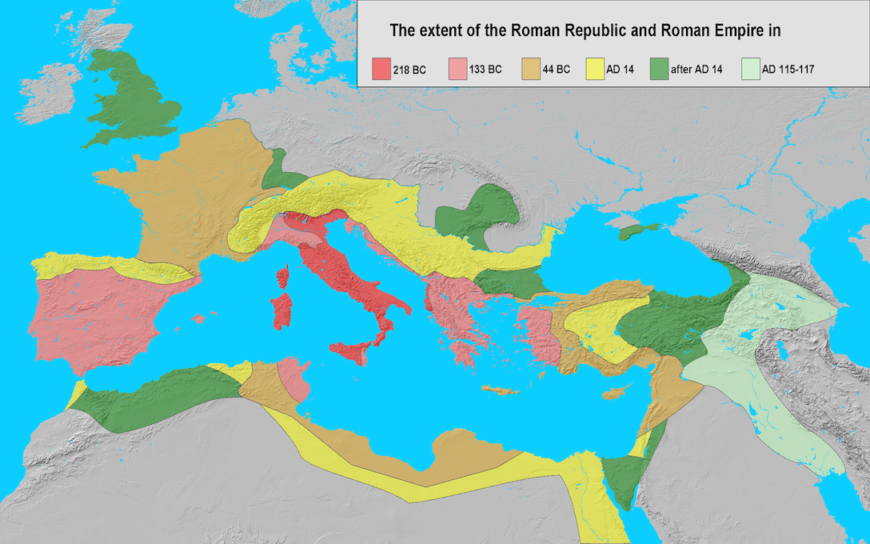

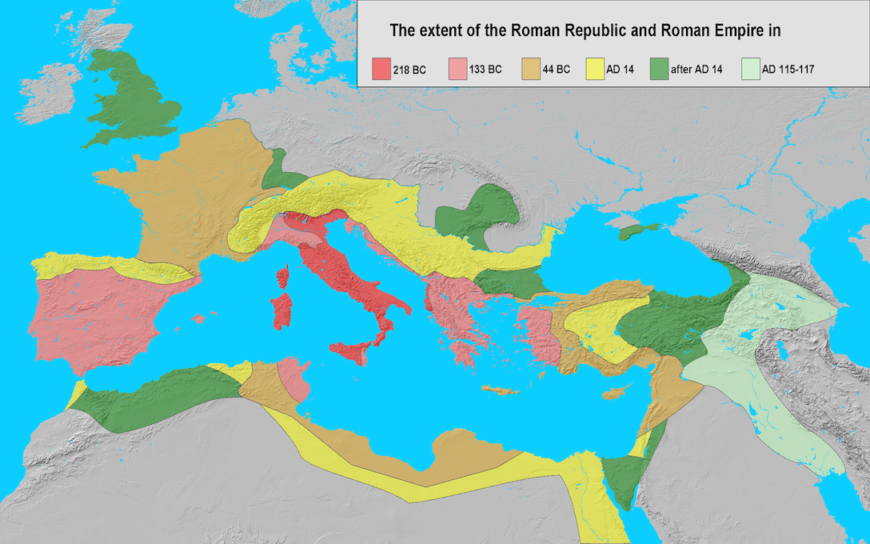

Successive emperors, such as Tiberius and Claudius, expanded Rome’s territory. By the time of the emperor Trajan, in the late first century C.E., the Roman empire, with about fifty million inhabitants, encompassed the whole of the Mediterranean, Britain, much of northern and central Europe, and the Near East.

Schematic map showing the territorial expansion of Rome from the Middle Republic to the death of the Emperor Trajan (map: Varana, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A vast empire

Starting with Augustus in 27 B.C.E., the emperors ruled for five hundred years. They expanded Rome’s territory and by about 200 C.E., their vast empire stretched from Syria to Spain and from Britain to Egypt. Networks of roads connected rich and vibrant cities, filled with beautiful public buildings. A shared Greco-Roman culture linked people, goods and ideas.

The imperial system of the Roman Empire depended heavily on the personality and standing of the emperor himself. The reigns of weak or unpopular emperors often ended in bloodshed at Rome and chaos throughout the empire as a whole. In the third century C.E. the very existence of the empire was threatened by a combination of economic crisis, weak and short-lived emperors and usurpers (and the violent civil wars between their rival supporting armies), and massive barbarian penetration into Roman territory.

Relative stability was re-established in the fourth century C.E., through the emperor Diocletian’s division of the empire. The empire was divided into eastern and western halves and then into more easily administered units. Although some later emperors such as Constantine ruled the whole empire, the division between east and west became more marked as time passed. Financial pressures, urban decline, underpaid troops, and consequently overstretched frontiers—all of these finally caused the collapse of the western empire under waves of barbarian incursions in the early fifth century C.E. The last western emperor, Romulus Augustus, was deposed in 476 C.E., though the empire in the east, centered on Byzantium (Constantinople), continued until the fifteenth century.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Introduction to Roman Beliefs and Pantheon

Early Beliefs and the Roman Pantheon

In many societies, ancient and modern, religion has performed a major role in their development, and the Roman Empire was no different. From the beginning Roman religion was polytheistic. From an initial array of gods and spirits, Rome added to this collection to include both Greek gods as well as a number of foreign cults.As the empire expanded, the Romans refrained from imposing their own religious beliefs upon those they conquered; however, this inclusion must not be misinterpreted as tolerance — this can be seen with their early reaction to the Jewish and Christian population. Eventually, all of their gods would be washed away, gradually replaced by Christianity, and in the eyes of some, this change brought about the decline of the western empire. (76)

Early Beliefs & Influences

Early forms of the Roman religion were animistic in nature, believing that spirits inhabited everything around them, people included. The first citizens of Rome also believed they were watched over by the spirits of their ancestors. Initially, a Capitoline Triad (possibly derived from a Sabine influence) were added to these “spirits” — the new gods included Mars, the god of war and supposed father of Romulus and Remus (founders of Rome); Quirinus, the deified Romulus who watched over the people of Rome; and lastly, Jupiter, the supreme god.

They, along with the spirits, were worshipped at a temple on Capitoline Hill. Later, due to the Etruscans, the triad would change to include Jupiter who remained the supreme god; Juno, his wife and sister; and Minerva, Jupiter’s daughter.

Due to the presence of Greek colonies on the Lower Peninsula, the Romans adopted many of the Greek gods as their own. Religion and myth became one. Under this Greek influence, the Roman gods became more anthropomorphic –with the human characteristics of jealousy, love, hate, etc. However, this transformation was not to the degree that existed in Greek mythology.

In Rome individual expression of belief was unimportant, strict adherence to a rigid set of rituals was far more significant, thereby avoiding the hazards of religious zeal. Cities adopted their own patron deities and performed their own rituals. Temples honoring the gods would be built throughout the empire; however, these temples were considered the “home” of the god; worship occurred outside the temple. While this fusion of Roman and Greek deities influenced Rome in many ways, their religion remained practical. (76)

The Roman Pantheon

While the study of Roman mythology tends to emphasize the major gods – Jupiter, Neptune (god of the sea), Pluto (god of the underworld) and Juno – there existed, of course, a number of “minor” gods and goddesses such as Nemesis, the god of revenge; Cupid, the god of love; Pax, the god of peace; and the Furies, goddesses of vengeance. However, when looking at the religion of Rome, one must examine the impact of the most important gods. Foremost among the gods were, of course, Jupiter, the Roman equivalent of Zeus (although not as playful), and his wife/sister Juno. He was the king of the gods; the sky god (the great protector) – controlling the weather and forces of nature, using thunderbolts to give warning to the people of Rome.

Originally linked with farming as Jupiter Elicius, his role changed as the city grew, eventually obtaining his own temple on Capitoline Hill. Later, he became Jupiter Imperator Invictus Triumphator – Supreme General, Unconquered, and ultimately, Jupiter Optimus Maximus – Best and Greatest. His supremacy would be temporarily set aside during the reign of Emperor Elagabalus who attempted to replace the religion of Rome with that of the Syrian god Elagabal. After the emperor’s assassination, his successor, Alexander Severus, returned Jupiter to his former glory.

Next, Jupiter’s wife/sister was Juno, for whom the month of June is named – she was the equivalent of the Greek Hera. Besides being the supreme goddess with a temple on Esquiline Hill, she was the goddess of light and moon, embodying all of the virtues of Roman matron hood – as Juno Lucina she became the goddess of childbirth and fertility.

After Juno comes Minerva, the Roman name for Athena (the patron goddess of Athens), and Mars, the god of war. According to legend, Minerva sprang from Jupiter’s head fully formed. She was the goddess of commerce, industry, and education. Later, she would be identified as a war goddess as well as the goddess of doctors, musicians and craftsmen.

Although no longer one of the Capitoline triad, Mars remained an important god to Rome — similar to Ares, the Greek god of war. As Mars the Avenger, this son of Juno and her relationship with a flower, had a temple dedicated to him by Emperor Augustus, honoring the death of Julius Caesar’s assassins. Roman commanders would make sacrifices to him before and after battles and Tuesday (Martes) is named for him.

There are a number of lesser gods (all with temples built to them) — Apollo, Diana, Saturn, Venus, Vulcan, and Janus. Apollo had no Roman equal and he was simply the Greek god of poetry, medicine, music, and science. He was originally brought to the city by the Etruscans to ward off the plague and was rewarded with a temple on Palatine Hill. Diana, Apollo’s Roman sister equivalent to the Greek Artemis, was not only the goddess of wild beasts and the harvest moon but also the goddess of the hunt. She was seen as a protector of women in childbirth with a temple at Ephesus in Asia Minor.

Another god brought to the Rome by the Etruscans was Saturn, an agricultural god equal to the Greek Cronus and who had been expelled from heaven by Jupiter. A festival in his honor, the Saturnalia, was held yearly between the 17 th and 23rd of December. His temple, at the foot of Capitoline Hill, housed the public treasury and decrees of the Senate. Another Roman goddess was Venus, who was born, according to myth, from the foam of the sea, equal to the Greek Aphrodite. According to Homer, she was the mother of Aenaes the hero of the Trojan War. Of course, the planet Venus is named for her.

Next was Vulcan, also expelled from heaven by Jupiter, who was a lame (caused by his expulsion), ugly blacksmith and the god of fire. Lastly, there was Janus who had no Greek equal. He was the two-faced guardian of doorways and public gates. Janus was valued for his wisdom and was the first god mentioned in a person’s prayer; because of his two faces he could see both the past and the future.

One cannot forget the Vestal Virgins who had no Greek counterpart. They were the guardians of the public hearth at the Atrium Vesta. They were girls chosen only from the patrician class at the tender age of six, beginning their service to the goddess Vesta at the age of ten and for the next thirty years they would serve her. While serving as a Vestal Virgin, a girl/woman was forbidden to marry and had to remain chaste. Some chose to remain in service to Vesta after serving their thirty years since, at the age of forty, they were considered too old to marry. Breaking the vow of chastity would result in death — only twenty would break the vow in over one thousand years. Emperor Elagabalus attempted to marry a vestal virgin but was convinced otherwise. (76)

CC licensed content, Shared previously

Introduction to Roman Art

With the lands of Greece, Egypt, and beyond, Ancient Rome was a melting pot of cultures.

View of the Roman forum, looking toward the Colosseum (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Roman art: when and where

Roman art is a very broad topic, spanning almost 1,000 years and three continents, from Europe and Africa and Asia. The first Roman art can be dated back to 509 B.C.E., with the legendary founding of the Roman Republic, and lasted until 330 C.E. (or much longer, if you include Byzantine art). Roman art also encompasses a broad spectrum of media including marble, painting, mosaic, gems, silver, bronze work, and terracottas, just to name a few. The city of Rome was a melting pot, and the Romans had no qualms about adapting artistic influences from the other Mediterranean cultures that surrounded and preceded them. For this reason it is common to see Greek, Etruscan, and Egyptian influences throughout Roman art. This is not to say that all of Roman art is derivative, though, and one of the challenges for specialists is to define what is “Roman” about Roman art.

Doryphoros (Spear Bearer), Roman copy after an original by the Greek sculptor Polykleitos from c. 450–40 B.C.E., marble, 211 cm high (Archaeological Museum, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Greek art certainly had a powerful influence on Roman practice; the Roman poet Horace famously said that “Greece, the captive, took her savage victor captive,” meaning that Rome (though it conquered Greece) adapted much of Greece’s cultural and artistic heritage (as well as importing many of its most famous works). It is also true that many Romans commissioned versions of famous Greek works from earlier centuries; this is why we often have marble versions of lost Greek bronzes such as the Doryphoros by Polykleitos.

The Romans did not believe, as we do today, that to have a copy of an artwork was of any less value that to have the original. The copies, however, were more often variations rather than direct copies, and they had small changes made to them. The variations could be made with humor, taking the serious and somber element of Greek art and turning it on its head. So, for example, a famously gruesome Hellenistic sculpture of the satyr Marsyas being flayed was converted in a Roman dining room to a knife handle (currently in the National Archaeological Museum in Perugia). A knife was the very element that would have been used to flay the poor satyr, demonstrating not only the owner’s knowledge of Greek mythology and important statuary, but also a dark sense of humor. From the direct reporting of the Greeks to the utilitarian and humorous luxury item of a Roman enthusiast, Marsyas made quite the journey. But the Roman artist was not simply copying. He was also adapting in a conscious and brilliant way. It is precisely this ability to adapt, convert, combine elements, and add a touch of humor that makes Roman art Roman.

Republican Rome

The mythic founding of the Roman Republic is supposed to have happened in 509 B.C.E., when the last Etruscan king, Tarquinius Superbus, was overthrown. During the Republican period, the Romans were governed by annually elected magistrates, the two consuls being the most important among them, and the Senate, which was the ruling body of the state. Eventually the system broke down and civil wars ensued between 100 and 42 B.C.E. The wars were finally brought to an end when Octavian (later called Augustus) defeated Mark Antony in the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E.

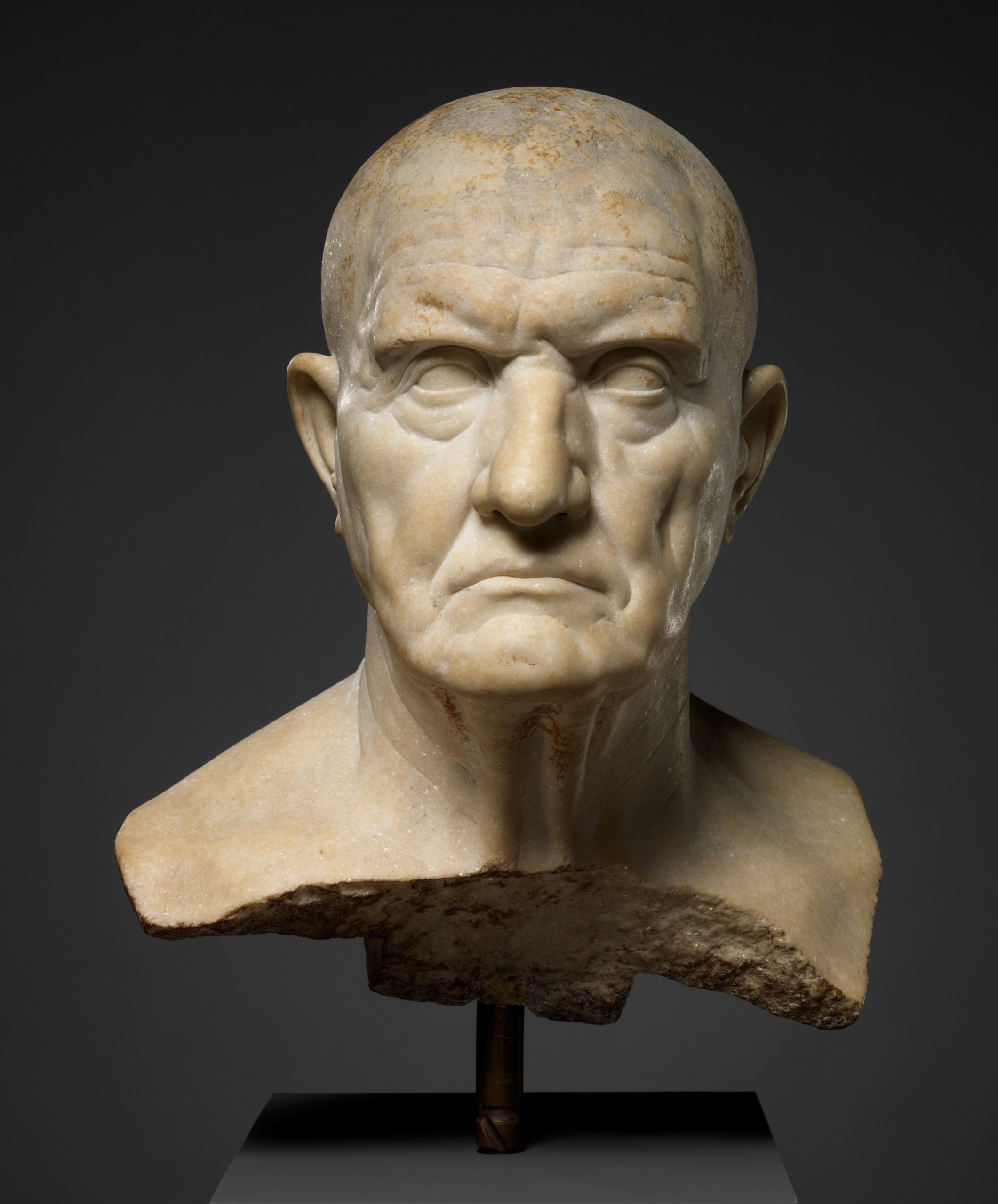

In the Republican period, art was produced in the service of the state, depicting public sacrifices or celebrating victorious military campaigns (like the Monument of Aemilius Paullus at Delphi). Portraiture extolled the communal goals of the Republic; hard work, age, wisdom, being a community leader and soldier. Patrons chose to have themselves represented with balding heads, large noses, and extra wrinkles, demonstrating that they had spent their lives working for the Republic as model citizens, flaunting their acquired wisdom with each furrow of the brow. We now call this portrait style veristic, referring to the hyper-naturalistic features that emphasize every flaw, creating portraits of individuals with personality and essence.

Imperial Rome

Augustus’s rise to power in Rome signaled the end of the Roman Republic and the formation of Imperial rule. Roman art was now put to the service of aggrandizing the ruler and his family. It was also meant to indicate shifts in leadership. The major periods in Imperial Roman art are named after individual rulers or major dynasties, they are:

- Augustan (27 B.C.E.–14 C.E.)

Julio-Claudian (14–68 C.E.)

Flavian (69–98 C.E.)

Trajanic (98–117 C.E.)

Hadrianic (117–38 C.E.)

Antonine (138–93 C.E.)

Severan (193–235 C.E.)

Soldier Emperor (235–84 C.E.)

Tetrarchic (284–312 C.E.)

Constantinian (307–37 C.E.)

Relief from the Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace), 9 B.C.E. monument is dedicated, marble (Museo dell’Ara Pacis, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Imperial art often hearkened back to the Classical art of the past. “Classical”, or “Classicizing,” when used in reference to Roman art refers broadly to the influences of Greek art from the Classical and Hellenistic periods (480–31 B.C.E.). Classicizing elements include the smooth lines, elegant drapery, idealized nude bodies, highly naturalistic forms and balanced proportions that the Greeks had perfected over centuries of practice.

Augustus of Primaporta, 1st century C.E. (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Augustus and the Julio-Claudian dynasty were particularly fond of adapting Classical elements into their art. The Augustus of Primaporta was made at the end of Augustus’s life, yet he is represented as youthful, idealized and strikingly handsome like a young athlete—all hallmarks of Classical art. The emperor Hadrian was known as a philhellene, or lover of all things Greek. The emperor himself began sporting a Greek “philosopher’s beard” in his official portraiture, unheard of before this time. Décor at his rambling Villa at Tivoli included mosaic copies of famous Greek paintings, such as Battle of the Centaurs and Wild Beasts by the legendary ancient Greek painter Zeuxis.

Pair of Centaurs Fighting Cats of Prey from Hadrian’s Villa, mosaic, c. 130 C.E. (Altes Museum, Berlin, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

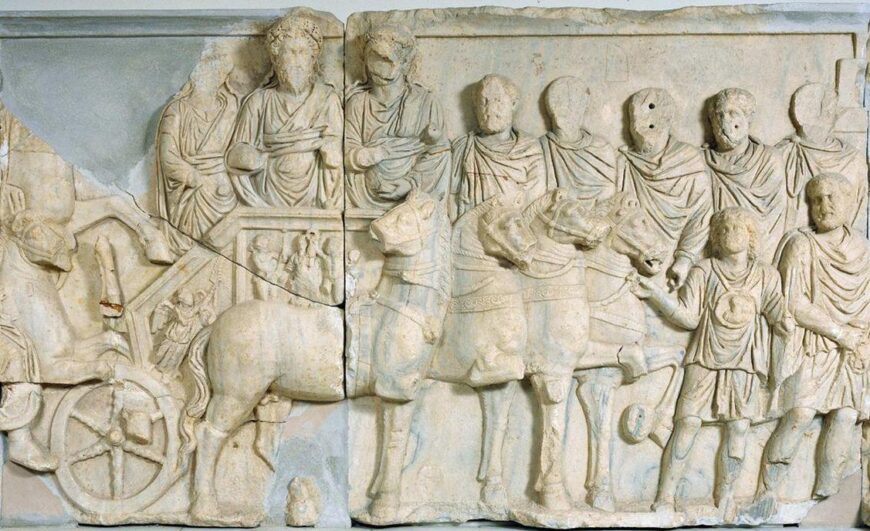

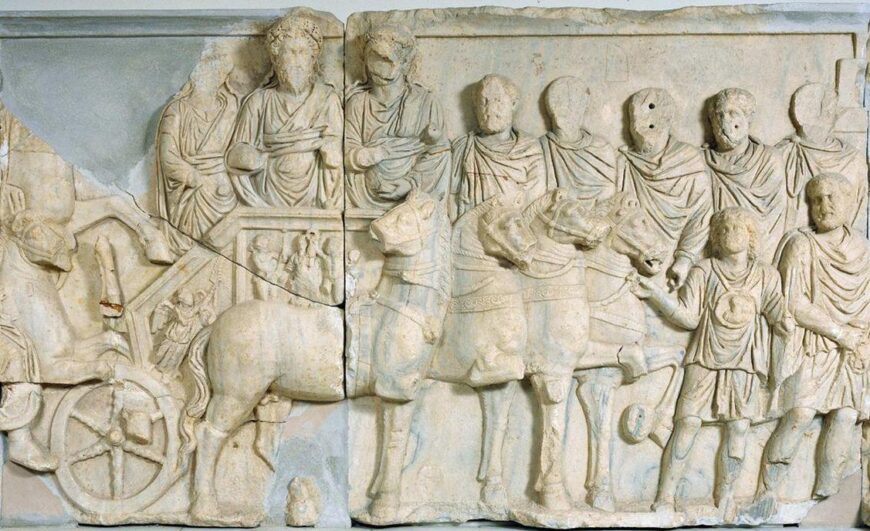

Later Imperial art moved away from earlier Classical influences, and Severan art signals the shift to art of Late Antiquity. The characteristics of Late Antique art include frontality, stiffness of pose and drapery, deeply drilled lines, less naturalism, squat proportions, and lack of individualism. Important figures are often slightly larger or are placed above the rest of the crowd to denote importance.

Chariot procession of Septimus Severus, relief from the attach of the Arch of Septimus Severus, Leptis Magna, Libya, 203 C.E., marble, 167 cm high (Red Castle Museum, Tripoli)

In relief panels from the Arch of Septimius Severus from Lepcis Magna, Septimius Severus and his sons, Caracalla and Geta ride in a chariot, marking them out from an otherwise uniform sea of repeating figures, all wearing the same stylized and flat drapery. There is little variation or individualism in the figures and they are all stiff and carved with deep, full lines. There is an ease to reading the work; Septimius is centrally located, between his sons and slightly taller; all the other figures direct the viewer’s eyes to him.

Relief from the Arch of Constantine, 315 C.E., Rome (photo: F. Tronchin, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Constantinian art continued to integrate the elements of Late Antiquity that had been introduced in the Severan period, but they are now developed even further. For example, on the oratio relief panel on the Arch of Constantine, the figures are even more squat, frontally oriented, similar to one another, and there is a clear lack of naturalism. Again, the message is meant to be understood without hesitation: Constantine is in power.

Who made Roman art?

We don’t know much about who made Roman art. Artists certainly existed in antiquity but we know very little about them, especially during the Roman period, because of a lack of documentary evidence such as contracts or letters. What evidence we do have, such as Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, pays little attention to contemporary artists and often focuses more on the Greek artists of the past. As a result, scholars do not refer to specific artists but consider them generally, as a largely anonymous group.

Painted Garden, removed from the triclinium (dining room) in the Villa of Livia Drusilla, Prima Porta, fresco, 30–20 B.C.E. (Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What did they make?

Roman art encompasses private art made for Roman homes as well as art in the public sphere. The elite Roman home provided an opportunity for the owner to display his wealth, taste and education to his visitors, dependents, and clients. Since Roman homes were regularly visited and were meant to be viewed, their decoration was of the utmost importance. Wall paintings, mosaics, and sculptural displays were all incorporated seamlessly with small luxury items such as bronze figurines and silver bowls. The subject matter ranged from busts of important ancestors to mythological and historical scenes, still lifes, and landscapes—all to create the idea of an erudite patron steeped in culture.

Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus: Battle of Romans and Barbarians, c. 250–60 C.E., preconneus marble, 150 cm high (Palazzo Altemps: Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

When Romans died, they left behind imagery that identified them as individuals. Funerary imagery often emphasized unique physical traits or trade, partners or favored deities. Roman funerary art spans several media and all periods and regions. It included portrait busts, wall reliefs set into working-class group tombs (like those at Ostia), and elite decorated tombs (like the Via delle Tombe at Pompeii). In addition, there were painted Faiyum portraits placed on mummies and sarcophagi. Because death touched all levels of society—men and women, emperors, elites, and freedmen—funerary art recorded the diverse experiences of the various peoples who lived in the Roman empire

Column of Trajan, Carrera marble, completed 113 C.E., Rome, dedicated to Emperor Trajan in honor of his victory over Dacia (now Romania) 101–02 and 105–06 C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The public sphere is filled with works commissioned by the emperors such as portraits of the imperial family or bath houses decorated with copies of important Classical statues. There are also commemorative works like the triumphal arches and columns that served a didactic as well as a celebratory function. The arches and columns (like the Arch of Titus or the Column of Trajan), marked victories, depicted war, and described military life. They also revealed foreign lands and enemies of the state. They could also depict an emperor’s successes in domestic and foreign policy rather than in war, such as Trajan’s Arch in Benevento. Religious art is also included in this category, such as the cult statues placed in Roman temples that stood in for the deities they represented, like Venus or Jupiter. Gods and religions from other parts of the empire also made their way to Rome’s capital including the Egyptian goddess Isis, the Persian god Mithras, and ultimately Christianity. Each of these religions brought its own unique sets of imagery to inform proper worship and instruct their sect’s followers.

It can be difficult to pinpoint just what is Roman about Roman art, but it is the ability to adapt, to take in and to uniquely combine influences over centuries of practice that made Roman art distinct.

Additional resources

John R. Clarke, Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans: Visual Representation and Non-Elite Viewers in Italy, 100 B.C–A.D. 315 (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003).

Fred S. Kleiner, A History of Roman Art (Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth, 2007).

Nancy H. Ramage and Andrew Ramage. Roman Art: Romulus to Constantine, Fifth Edition (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc., 2008).

Peter Stewart, The Social History of Roman Art (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Paul Zanker, Roman Art (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010).

Introduction to Roman Architecture

Roman architecture was unlike anything that had come before. The Persians, Egyptians, Greeks and Etruscans all had monumental architecture. The grandeur of their buildings, though, was largely external. Buildings were designed to be impressive when viewed from outside because their architects all had to rely on building in a post-and-lintel system, which means that they used two upright posts, like columns, with a horizontal block, known as a lintel, laid flat across the top. A good example is this ancient Greek Temple in Paestum, Italy.

An example of post and lintel architecture: Hera II, Paestum, c. 460 B.C.E. (Classical period), tufa, 24.26 x 59.98 m

Since lintels are heavy, the interior spaces of buildings could only be limited in size. Much of the interior space had to be devoted to supporting heavy loads.

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Interior of the Pantheon, c. 1734, oil on canvas, 128 x 99 cm (National Gallery of Art)

Roman architecture differed fundamentally from this tradition because of the discovery, experimentation and exploitation of concrete, arches and vaulting (a good example of this is the Pantheon, c. 125 C.E.). Thanks to these innovations, from the first century C.E. Romans were able to create interior spaces that had previously been unheard of. Romans became increasingly concerned with shaping interior space rather than filling it with structural supports. As a result, the inside of Roman buildings were as impressive as their exteriors.

Materials, methods and innovations

Long before concrete made its appearance on the building scene in Rome, the Romans utilized a volcanic stone native to Italy called tufa to construct their buildings. Although tufa never went out of use, travertine began to be utilized in the late 2nd century B.C.E. because it was more durable. Also, its off-white color made it an acceptable substitute for marble.

Temple of Portunus (formerly known as, Fortuna Virilis), c. 120-80 B.C.E., structure is travertine and tufa, stuccoed to look like Greek marble, Rome

Marble was slow to catch on in Rome during the Republican period since it was seen as an extravagance, but after the reign of Augustus (31 B.C.E. – 14 C.E.), marble became quite fashionable. Augustus had famously claimed in his funerary inscription, known as the Res Gestae, that he “found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble” referring to his ambitious building campaigns.

Roman concrete (opus caementicium), was developed early in the 2nd c. BCE. The use of mortar as a bonding agent in ashlar masonry wasn’t new in the ancient world; mortar was a combination of sand, lime and water in proper proportions. The major contribution the Romans made to the mortar recipe was the introduction of volcanic Italian sand (also known as “pozzolana”). The Roman builders who used pozzolana rather than ordinary sand noticed that their mortar was incredibly strong and durable. It also had the ability to set underwater. Brick and tile were commonly plastered over the concrete since it was not considered very pretty on its own, but concrete’s structural possibilities were far more important. The invention of opus caementicium initiated the Roman architectural revolution, allowing for builders to be much more creative with their designs. Since concrete takes the shape of the mold or frame it is poured into, buildings began to take on ever more fluid and creative shapes.

True arch (left) and corbeled arch (right) (image, CC BY-SA 2.5)

The Romans also exploited the opportunities afforded to architects by the innovation of the true arch (as opposed to a corbeled arch where stones are laid so that they move slightly in toward the center as they move higher). A true arch is composed of wedge-shaped blocks (typically of a durable stone), called voussoirs, with a key stone in the center holding them into place. In a true arch, weight is transferred from one voussoir down to the next, from the top of the arch to ground level, creating a sturdy building tool. True arches can span greater distances than a simple post-and-lintel. The use of concrete, combined with the employment of true arches allowed for vaults and domes to be built, creating expansive and breathtaking interior spaces.

Roman architects

We don’t know much about Roman architects. Few individual architects are known to us because the dedicatory inscriptions, which appear on finished buildings, usually commemorated the person who commissioned and paid for the structure. We do know that architects came from all walks of life, from freedmen all the way up to the Emperor Hadrian, and they were responsible for all aspects of building on a project. The architect would design the building and act as engineer; he would serve as contractor and supervisor and would attempt to keep the project within budget.

Building types

Forum, Pompeii, looking toward Mt. Vesuvius (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Roman cities were typically focused on the forum (a large open plaza, surrounded by important buildings), which was the civic, religious and economic heart of the city. It was in the city’s forum that major temples (such as a Capitoline temple, dedicated to Jupiter, Juno and Minerva) were located, as well as other important shrines. Also useful in the forum plan were the basilica (a law court), and other official meeting places for the town council, such as a curia building. Quite often the city’s meat, fish and vegetable markets sprang up around the bustling forum. Surrounding the forum, lining the city’s streets, framing gateways, and marking crossings stood the connective architecture of the city: the porticoes, colonnades, arches and fountains that beautified a Roman city and welcomed weary travelers to town. Pompeii, Italy is an excellent example of a city with a well preserved forum.

House of Diana, Ostia, late 2nd century C.E. (photo: Sebastià Giralt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Romans had a wide range of housing. The wealthy could own a house (domus) in the city as well as a country farmhouse (villa), while the less fortunate lived in multi-story apartment buildings called insulae. The House of Diana in Ostia, Rome’s port city, from the late 2nd c. C.E. is a great example of an insula. Even in death, the Romans found the need to construct grand buildings to commemorate and house their remains, like Eurysaces the Baker, whose elaborate tomb still stands near the Porta Maggiore in Rome.

The tomb of Eurysaces the baker, Rome, c. 50-20 B.C.E. (photo: Jeremy Cherfas, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Romans built aqueducts throughout their domain and introduced water into the cities they built and occupied, increasing sanitary conditions. A ready supply of water also allowed bath houses to become standard features of Roman cities, from Timgad, Algeria to Bath, England. A healthy Roman lifestyle also included trips to the gymnasium. Quite often, in the Imperial period, grand gymnasium-bath complexes were built and funded by the state, such as the Baths of Caracalla which included running tracks, gardens and libraries.

Aqueduct (reconstruction). Aqueducts supplied Rome with clean water brought from sources far from the city. In this view, we see an aqueduct carried on piers passing through a built-up neighborhood. Elements of the model © 2008 The Regents of the University of California, © 2011 Université de Caen Basse-Normandie, © 2012 Frischer Consulting. All rights reserved. Image © 2012 Bernard Frischer

Entertainment varied greatly to suit all tastes in Rome, necessitating the erection of many types of structures. There were Greek style theaters for plays as well as smaller, more intimate odeon buildings, like the one in Pompeii, which were specifically designed for musical performances. The Romans also built amphitheaters—elliptical, enclosed spaces such as the Colloseum—which were used for gladiatorial combats or battles between men and animals. The Romans also built a circus in many of their cities. The circuses, such as the one in Lepcis Magna, Libya, were venues for residents to watch chariot racing.

Arch of Titus (foreground) with the Colloseum in the background (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Romans continued to perfect their bridge building and road laying skills as well, allowing them to cross rivers and gullies and traverse great distances in order to expand their empire and better supervise it. From the bridge in Alcántara, Spain to the paved roads in Petra, Jordan, the Romans moved messages, money and troops efficiently.

Republican period

Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Capitoline Hill, Rome (reconstruction courtesy Dr. Bernard Frischer)

Republican Roman architecture was influenced by the Etruscans who were the early kings of Rome; the Etruscans were in turn influenced by Greek architecture. The Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill in Rome, begun in the late 6th century B.C.E., bears all the hallmarks of Etruscan architecture. The temple was erected from local tufa on a high podium and what is most characteristic is its frontality. The porch is very deep and the visitor is meant to approach from only one access point, rather than walk all the way around, as was common in Greek temples. Also, the presence of three cellas, or cult rooms, was also unique. The Temple of Jupiter would remain influential in temple design for much of the Republican period.

Drawing on such deep and rich traditions didn’t mean that Roman architects were unwilling to try new things. In the late Republican period, architects began to experiment with concrete, testing its capability to see how the material might allow them to build on a grand scale.

Model of the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia, from the archeological museum, Palestrina (image, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia in modern day Palestrina is comprised of two complexes, an upper and a lower one. The upper complex is built into a hillside and terraced, much like a Hellenistic sanctuary, with ramps and stairs leading from the terraces to the small theater and tholos temple at the pinnacle. The entire compound is intricately woven together to manipulate the visitor’s experience of sight, daylight and the approach to the sanctuary itself. No longer dependent on post-and-lintel architecture, the builders utilized concrete to make a vast system of covered ramps, large terraces, shops and barrel vaults.

Imperial period

Severus and Celer, octagon room, Domus Aurea, Rome, c. 64-68 C.E. (photo source)

The Emperor Nero began building his infamous Domus Aurea, or Golden House, after a great fire swept through Rome in 64 C.E. and destroyed much of the downtown area. The destruction allowed Nero to take over valuable real estate for his own building project; a vast new villa. Although the choice was not in the public interest, Nero’s desire to live in grand fashion did spur on the architectural revolution in Rome. The architects, Severus and Celer, are known (thanks to the Roman historian Tacitus), and they built a grand palace, complete with courtyards, dining rooms, colonnades and fountains. They also used concrete extensively, including barrel vaults and domes throughout the complex. What makes the Golden House unique in Roman architecture is that Severus and Celer were using concrete in new and exciting ways; rather than utilizing the material for just its structural purposes, the architects began to experiment with concrete in aesthetic modes, for instance, to make expansive domed spaces.

Apollodorus of Damascus, Markets of Trajan, Rome, c. 106-12 C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Nero may have started a new trend for bigger and better concrete architecture, but Roman architects, and the emperors who supported them, took that trend and pushed it to its greatest potential. Vespasian’s Colosseum, the Markets of Trajan, the Baths of Caracalla and the Basilica of Maxentius are just a few of the most impressive structures to come out of the architectural revolution in Rome. Roman architecture was not entirely comprised of concrete, however. Some buildings, which were made from marble, hearkened back to the sober, Classical beauty of Greek architecture, like the Forum of Trajan. Concrete structures and marble buildings stood side by side in Rome, demonstrating that the Romans appreciated the architectural history of the Mediterranean just as much as they did their own innovation. Ultimately, Roman architecture is overwhelmingly a success story of experimentation and the desire to achieve something new.

Additional resources:

James C. Anderson Jr., Roman Architecture and Society (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

Diana Kleiner, Roman Architecture: A Visual Guide (Kindle) (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014).

William J. MacDonald, The Architecture of the Roman Empire, vol. I: An Introductory Study (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982).

Frank Sear, Roman Architecture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983).

J.B. Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

Italo-Roman Building Techniques

Isili, Sardinia: exterior of Nuraghe Is Paras, fifteenth century B.C.E., (photo: Cristiano Cani, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Building techniques represent an important means through which to study and understand ancient structures. The building technique chosen for a given project can indirectly provide a good deal of information about the building itself, in terms of helping archaeologists and art historians to understand scale, scope, expense, and technique, alongside other, more aesthetic considerations. The building technique can also inform the chronology of the structure and can indicate, in some cases, other economic factors based on the building materials employed. The masonry techniques discussed here cover a broad chronological range from the second millennium B.C.E. to Late Antiquity.

Megalithic techniques

From the second millennium B.C.E. onwards techniques of megalithic architecture were used in Italy and on the island of Sardinia. As the name suggests, such techniques involved the use of large unworked (or roughly worked) stones to create walls and structures. Such walls tend to be built in a dry stone technique, meaning that no bonding agents are used to join stones, rather the tight fit and gravity itself are relied upon to hold the stones in place. Such techniques are frequently referred to under the general heading of “Cyclopean masonry”, indicative of the great bulk of the stones used.

Isili, Sardinia: Interior of Nuraghe Is Paras, fifteenth century B.C.E., (photo: Cristiano Cani, CC BY-SA 3.0)

On Sardinia, distinctive tower structures known as nuraghe built during the second and first millennia B.C.E. utilized megalithic techniques, including the construction of corbel vaults. In peninsular Italy, the distinctive style of polygonal masonry emerged by the second half of the first millennium B.C.E. Often used to construct defensive walls, retaining walls, and terraces, this type of megalithic architecture assumed a distinctive polygonal pattern.

Amelia, Italy: detail of polygonal masonry wall of the ancient city of Ameria (photo: Ameroe, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Ashlar masonry (opus quadratum)

Ashlar or cuboidal masonry (cut, squared stones), referred to as opus quadratum by the Romans, represents an important advance in building technology. In Italy, the widespread use of ashlar masonry occurs from the sixth century B.C.E. onward. At Rome, this adoption corresponded to a marked increase in monumental construction projects during the late archaic period. Initially, Romans made use of a locally available tufo type known as cappellaccio. While a prestige material, its overall low quality led to the Romans being eager for other sources of superior tufo — a new source of tufo became available once Rome sacked the Etruscan city of Veii in 396 B.C.E.

Rome, Italy: Segment of the so-called “Servian walls” in Piazza dei Cinquecento, fourth century B.C.E. (photo: Salvatore Falco, CC SA 1.0)

Ashlar masonry, in general, is used primarily where underlying bedrock is softer and more easily shaped, such as the tufo plateaus on which the city of Rome and many of her Etruscan neighbors sit. Ashlar masonry is phased in for use in monumental construction projects. Notable examples in the city of Rome include the so-called “Servian walls” surrounding the city of Rome and the late sixth century B.C.E. podium of the Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus. Although ashlar techniques would never completely disappear, the emergence of Roman concrete (opus caementicium) during the second century B.C.E. came to offer greater flexibility and strength than ashlar masonry could.

Rome, Italy: podium of the Temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus, late sixth century B.C.E. (photo: Torquatus, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Opus caementicium (“cement work”)

“Roman concrete” describes a category of building technology that involves the use of concrete. Concrete is defined as a heavy, durable building material made from a mixture of sand, lime, water, and inclusions (caementa) such as stone, gravel or terracotta. It can either be spread or poured into molds or frames; it forms a stone-like mass upon hardening. In chronological terms, the ancient Roman usage of concrete stretches from sometime in the second century B.C.E. to Late Antiquity (and beyond). Within that chronological span, the technology of concrete changed and developed over time so that we may observe differences that relate to both function and aesthetics.

The basic concept of Roman concrete walling is to create a concrete core that is then faced with stone or brick and perhaps faced even further with stucco, paint, or polished stone veneers. Roman concrete is strong, practical, and functional — it is, on its own, rarely deemed aesthetically beautiful but its versatility and load-bearing potential facilitated the construction of many of the most famous buildings of Roman antiquity. The trio of the Domus Aurea of Nero, the Flavian Amphitheater, and the Pantheon could never have been realized without the innovative use of concrete building technology.

Italy, Rome, Via Appia Antica, tomb. The remains show the internal core of the building, made in Roman concrete (opus caementicium). Photo: MM, CC0

Roman concrete is famously strong and durable — even in archaeological contexts concrete is remarkable for its longevity. While the Romans did not invent concrete per se, they improved their own version of concrete by means of additions to its formula. Volcanic sand known as pozzolana (or “pit sand”) was favored by Roman builders for mixing concrete. When pozzolana, which contains high quantities of both aluminum oxide (sometimes called alumina) and silica, was added to mortar, the water-resistant properties of the mortar increased. This hydraulic concrete was then ideal for use in building piers, breakwaters, and bridge pylons, among other structures.

Typology

The Roman architectural writer Vitruvius (first century B.C.E.) provides a thorough summary of building techniques in his 10-book treatise De architectura (“On architecture”). In most cases, modern scholars continue to employ the Latin terminology used by Vitruvius. In these typological categories, the Latin term opus means “work or technique”.

Terracina, Italy: Opus incertum used in the podium of the temple of Iuppiter Anxur (photo: Xavier121, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Opus incertum (“irregular work”) is an early concrete technique that emerged during the earlier second century B.C.E. and continued in use until the middle of the first century B.C.E., gradually abandoned in favor of opus reticulatum. Opus incertum may be identified on the basis of its use of randomly placed, fist-sized chunks of tufo or stone that are placed into a core of opus caementicium.

An example of opus reticulatum (photo: Pouwerkerk, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Opus reticulatum (“reticulate work”) is a technique that employs diamond-shaped pieces of tufo known as cubilia that are placed within a core of concrete. The resulting pattern of the flat ends of these blocks form the net-shaped pattern that lends its name to the technique. Opus reticulatum became popular during the early first century B.C.E. It would eventually be superseded by opus latericium.

Ostia Antica: example of opus latericium (photo: Camelia.boban, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Opus latericium (“brickwork”) describes a masonry technique that employs courses of laid bricks that are used to face a wall core of opus caementicium. This is a predominant technique during the Roman Imperial period. The bricks, in turn, would often be coated with stucco or another form of wall revetment.

Ostia Antica: example of opus mixtum (photo: Camelia.boban, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Opus mixtum (“mixed work”) is a technique that combines opus reticulatum with opus latericium. The latter is usually found at the margins of the wall. It is a technique most common during the Hadrianic period in the mid-second century C.E.

Ostia Antica: example of opus vittatum (photo: Camelia.boban, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Opus vittatum or opus listatum is a later Roman concrete technique that is adopted in the early fourth century C.E. This technique alternated horizontal courses of tufo with alternating courses of bricks. This technique is particularly evident in building projects of Constantine I.

Additional resources:

Jean Pierre Adam, Roman building: materials and techniques (trans. Anthony Matthews) (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994).

Larry F. Ball, The Domus Aurea and the Roman architectural revolution (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Marion E. Blake, Ancient Roman Construction in Italy from the Prehistoric Period to Augustus. (Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1947).

Marion E. Blake, Construction in Italy from Tiberius through the Flavians. (Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1959).

C. J. Brandon et al., Building for eternity: the history and technology of Roman concrete engineering in the sea (Oxford: Oxbow, 2014).

Pierre Gros, L’architecture romaine: du début du IIIe siècle av. J.-C. à la fin du Haut-Empire. 1, Les monuments publics (Paris: Picard, 1996).

Cairoli Fulvio Giuliani, L’edilizia nell’antichità (Rome: NIS, 1990).

Lynne Lancaster, Concrete vaulted construction in imperial Rome: innovations in context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Lynne Lancaster, Innovative vaulting in the architecture of the Roman Empire: 1st to 4th centuries CE (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Giuseppe Lugli, La tecnica edilizia romana con particolare riguardo a Roma e Lazio 2 v. (Rome: G. Bardi, 1957).

David Macaulay, City: A Story of Roman Planning and Construction (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1974).

William L. MacDonald, The Architecture of the Roman Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965).

William L. MacDonald, The Pantheon: Design, Meaning and Progeny (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976).

Carmelo G. Malacrino, Constructing the Ancient world: architectural techniques of the Greeks and Romans (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010).

Esther Boise van Deman, “Methods of Determining the Date of Roman Concrete Monuments,” American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Apr. – Jun., 1912), pp. 230-251.

John Bryan Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

An Overview of the city of Rome

Temple of Vesta, The Roman Forum (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Eternal City

Rome is often described as the “eternal city,” conveying the idea that it lives (and has lived) forever, perhaps even suggesting a sort of unchanging immortality. However, even those things that are iconically eternal have a beginning. The humble beginnings of Rome provide the roots of a long cultural story, one that we continue to experience, sample, and live via archaeology, history, and cultural reception.

Romulus—Rome’s legendary founder—is said to have been suckled by a she-wolf, to have slain his own brother, and to have instituted the bellicose, strong, and independent character of the populus Romanus (“the Roman people”). The history and archaeology of the city that Romulus is credited with founding are inextricably wrapped up in layers of myth and folklore that helped Romans to tell their own story and generate collective memories in the urban space. For many archaeologists, these legends that describe the foundation of the city of Rome are fantastical and represent an attempt to explain not only how the city came to be founded, but also to establish ties between the city center and the surrounding areas of central Italy. The perspective offered by archaeological evidence allows us to examine the earliest phases of the city and the settlements that would have been founded there and to see the places in which myth and reality intersect. The legends and folklore also need testing, especially since blind acceptance of them has reinforced stereotypes about the city of Rome and its people that may not be representative of reality.

Model of Rome in the Archaic period with a view of the Capitol and the Forum (Musée de la Civilisation Romaine, Rome)

Legends aside, Rome’s earliest beginnings are humble and relatively ordinary. Settlements of smaller size that often occupy naturally defensible hilltops characterize the Iron Age in central Italy. Legends aside, Rome’s earliest beginnings are humble and relatively ordinary.

The Iron Age in central Italy is characterized by small settlements that often occupy naturally defensible hilltops. By the eighth century B.C.E., changes in settlement types became evident. These changes involve a reallocation of space and a movement toward nucleation—that is the clustering of population in a more densely populated center as opposed to a lower density scattering of small settlements across the landscape. In the immediate neighborhood of Rome, this is first evident in Latin settlements (for instance, near Gabii to the east of Rome), as well as in Etruscan settlements in south Etruria, for example Veii and Tarquinii.

Map showing Latin settlements in central Italy (and, toward the north, Etruscan sites in Southern Etruria) (map, Cassius Ahenobarbus, CC BY-SA 3.0)

It is as a result of this phenomenon that the historical Rome comes into being. Today archaeologists often refer to “early Rome” as a way to describe the early phases of the city that correspond to the Iron Age. The legendary actions of Romulus were believed to have taken place in the year 753 B.C.E. As a result of Romulus’ actions, the Palatine Hill was thought to have been surrounded by a fortification wall. Archaeological investigation of the Palatine Hill itself has revealed important clues about the earliest days of the city of Rome, including traces of an early wall surrounding at least some part of the Palatine Hill. This wall may be referred to as the “wall of Romulus” or murus Romuli (and should not be confused with the later “Servian wall”).[1]

A model of the Iron Age village on the Palatine Hill (photo: Kathryn Arnold, CC BY-SA 4.0)

“The Palatine City” and the “Hut of Romulus”

The agglomeration of Iron Age huts on the Palatine Hill is representative of the type of settlement commonly found in central Tyrrhenian Italy during the early Iron Age—relatively small in size and taking advantage of naturally defensible positions. The typical Iron Age hut in central Italy is a one-room structure with an oval ground plan. Its roof is of thatching that is supported by a wooden roof tree while its walls are generally made from a technique called wattle-and-daub which is essentially mud plaster applied over a framework of organic material. These huts served multiple functions, including processing and storage. In addition to the examples known from the site of Rome, we can see evidence for similar building types among the Etruscans and the Latins. Some assistance in reconstructing the appearance of these huts is offered by contemporary cinerary urns that take the shape of a hut, earning them the moniker “hut urns”. These urns may represent the economic status of the deceased person.

The Great Drain and the emergence of the Forum Romanum

The valley that is framed by the Palatine, Esquiline, and Capitoline hills (what we today call the Forum Romanum—the Roman Forum) was originally not a settlement area, but rather a space that lay outside of settlement limits.

The usability of this valley was compromised by the fact that periodic, seasonal flooding of the Tiber river, coupled with natural surface water, could render the valley wet and marshy. Since this area lay outside of settlement limits, it came to be used for both inhumation and cremation burials as was customary in the Iron Age. As Rome was beginning to coalesce, however, this space came to be of interest to the nascent city and its use was re-tasked. This meant that both human behavior and natural events had to be checked. For the former, human burials in the valley needed to cease, with burial activity being transferred to another location on the far side of the Esquiline Hill. Curbing nature was a larger challenge and it involved an impressive example of the early state organizing labor and resources to raise the surface level of the Forum valley through an artificial landfill project. This project involved the manual gathering and dumping of soil in the forum valley in order to raise the surface level by several meters. This would have required upwards of over 35,000 cubic feet of landfill to accomplish.

In connection with the landfill project was the creation of a channelized drain dubbed the Cloaca Maxima (“great drain”) that drained water away from the valley, through the area of the Velabrum, to the Tiber river. While initially an open drain, the Cloaca Maxima was eventually covered by vaulted masonry.

The poliadic temple—Jupiter Best and Greatest

The chief deity of the Roman people is the sky god Jupiter whose cult is connected in the legendary history with the earliest days of Rome. By the later sixth century B.C.E. a massive building project organized by the last of Rome’s Archaic kings was taking shape, namely creating a chief civic temple dedicated to IUPPITER OPTIMUS MAXIMUS or “Jupiter Best and Greatest.” Perched atop the Capitoline Hill, the temple of Jupiter would remain the focus of the Roman state religion for a millennium to come. Sacro-civic architecture of this type draws on central Italian architectural models and, in terms of urban life, provides a focused location for key events of the state’s ritual activity.

Left: reconstruction (in plexiglass) of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus revealing the foundations below, which can be seen today in the Capitoline Museum (right).

The river harbor and the “Cattle market”

Another important area of activity in the early city is the area surrounding the river harbor on the Tiber River, a space usually referred to as the Forum Boarium (“Cattle market”). The harbor provided a place where river-borne craft could put-in to shore in order to engage in commerce. Archaeological evidence suggests that this area is early on a focus of regional economic interchange and it takes advantage of a key point on the Tiber river, given that this is one of the only natural fords or crossing points in the lower extent of the river.

Reconstruction of the imperial Rome (4th century C.E.), by Italo Gismondi (photo: Sebastià Giralt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The twin temples in the archaeological site today known as the “Sacred Area of Sant’Omobono” is connected with the commercial function of this zone. Its roofline decorations included a terracotta statue of Herakles who was connected legendarily to the area of the Forum Boarium and also served as patron of travelers and traders. Dedications at the twin temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta reflect the nature of this area as a place of commerce and interchange. Like the Capitoline temple of Jupiter, these temples draw on central Italic traditions in terms of their architecture.

The foundations of the city and its growth in the Archaic period set the stage for its next phase. Tradition holds that Rome expelled her Archaic kings in 509 B.C.E., ushering in a period when a reshuffling of governmental structures would create a republican system. This new system of government also brought with it implications for the development of the city of Rome and the role played by art and architecture.

Notes

1. See T.P. Wiseman, “Review: Reading Carandini,” The Journal of Roman Studies 91 (2001) pp. 182-193; Roberto Suro, “Newly Found Wall May Give Clue To Origin of Rome, Scientist Says: When Did Rome Become Rome? Wall May Give Clue,” The New York Times (10 June 1988), p. A1; Henry R. Hurst, “The ‘Murus Romuli’ at the Northern Corner of the Palatine and the Porta Romanula : a Progress Report,” in Res Bene Gestae: ricerche di storia urbana su Roma antica in onore di Eva Margareta Steinby, edited by Anna Leone et al, pp. 79-102 (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 2007); Andrea Carandini et al. The Atlas of Ancient Rome: Biography and Portraits of the City 2 volumes (Princeton University Press, 2017). Table 62.

Additional Resources

Capitoline Museums – via Google Arts and Culture

Digitales Forum Romanum

Albert J. Ammerman, “On the Origins of the Forum Romanum,” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 94, no. 4, 1990, pp. 627-645. http://www.jstor.org/stable/505123

Andrea Carandini et al. The Atlas of Ancient Rome: Biography and Portraits of the City 2 v. (Princeton University Press, 2017).

The Atlas of Ancient Rome

Isabella Damiani, Claudio Parisi Presicce (eds.), La Roma dei Re: Il racconto dell’archeologia (Gangemi Editore, 2019).

Alexandre Grandazzi, The Foundation of Rome: Myth and History, trans. Jane Marie Todd (Cornell University Press, 1997).

John N. Hopkins, The Genesis of Roman Architecture (New Haven: Yales University Press, 2016).

C. J. Smith, Early Rome and Latium: Economy and Society c. 1000 to 500 BC. (Oxford University Press, 1996).

N. Terrenato, Brocato, P., Caruso, G., Ramieri, A.M., Becker, H.W., Cangemi, I., Mantiloni, G. and Regoli, C. “The S. Omobono Sanctuary in Rome: Assessing eighty years of fieldwork and exploring perspectives for the future,” Internet Archaeology 31 (2012).

Funerary Rituals and Social Status in Ancient Rome

Death, memory, and funerary rituals—monumental tombs lined the streets leading into ancient Roman cities.

Tombs along the Via Appia, Rome

To say that the ancient Romans thought a lot about funerary ritual and post-mortem commemoration is an understatement. Abundant textual evidence records complex, performative rituals surrounding death and burial in ancient Rome while significant expenditures on visual commemoration—elaborate tombs, funerary portraits—defined Roman mortuary culture.

Cemeteries and tombs lined extra-urban roads throughout the Roman world so that the mere act of exiting or entering a city brought one into immediate and direct contact with the world of the dead. In fact, Roman funerary art was not marginalized within Roman visual culture but was an integral part of it and constitutes one of the largest surviving bodies of evidence of Roman art.

Many conspicuous funerary monuments remain that commemorate the lives of elite Romans but members of other social strata also made sure to leave a lasting legacy and, indeed, funerary art is the only category of art that documents the lives of those outside of the elite. In ancient Rome, great opportunities for economic mobility existed and when people of the lower classes—former slaves (liberti) or members of a servile family—made money, they often wanted to commemorate their success by commissioning a tomb or grave marker that documented their rise to wealth. Two examples of surviving funerary monuments illustrate some of the these tendencies while providing a window into Roman funerary culture and art associated with freedmen and women, that is, people who were former slaves.

The Amiternum Tomb

Funerary procession, Amiternum, c. 50-1 B.C.E. (Museum, Aquila) (photo: Erin Taylor, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The first example is a late first century B.C.E. funerary relief from Amiternum (above), located in what is now the Abruzzo region of Italy. One relief depicts a person of some consequence and shows the only existing scene in Roman art of the pompa or funerary procession that was famously described by the historian Polybius (History 6.53-4). Roman funerals were often elaborate affairs that began in the house and culminated tombside. Upon death, dramatic displays of mourning were performed by household members of the deceased’s family. Such mourning rituals included wailing, chest-beating, and sometimes self-mutilation —pulling of the hair and laceration of the cheeks. The deceased’s corpse was then washed, anointed, and displayed on a funeral bed in the house before ultimately being transported to the tomb or site of cremation on an elaborate bier in a procession known as the pompa.

For elite Romans, the pompa was a dynamic performance defined less by solemnity and more by a multi-dimensional performance designed to reflect and reinforce political and social status. These spectacles featured not only the nuclear and extended biological family but also clients, current slaves, former slaves, hired mourners paid to wail and sing dirges, and musicians playing horns, flutes, and trumpets. For elite Roman men specifically, the procession culminated in the Forum with a public eulogy attended by male family members who would wear the ancestor masks depicting deceased male relatives.

Male figure on funerary couch surrounded by funeral cortège (detial), Funerary procession, Amiternum, c. 50-1 B.C.E. (Museum, Aquila) (photo: Erin Taylor, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In the relief from Amiternum, the pompa scene shows a male figure, resting on an elaborate funerary couch and transported by eight pallbearers (above). Though dead, the figure appears still very much alive—tilted up on his left side and resting his head on his left hand. On either side of the central scene are all the elements of a funeral cortège. On the right pipe players, with hornblowers and a trumpeter on a floating ground line above. To the immediate right of the deceased are two women, perhaps hired mourners, one grabbing her hair and the other with her hands upraised. Most likely it is the chief mourners—the widow and children—who follow behind, to the left of the deceased.

A partial inscription found near the relief suggests that the tomb was commissioned by a person whose family was formerly of servile origins. Stylistically, the relief exhibits many of the formal characteristics typical of ‘freedmen’ art, a category of art commissioned by former slaves (or descendants of slaves) and one which largely rejected the Classicizing trappings of elite Roman art. Art commissioned by freedmen and women typically exhibits disproportion, hierarchies of scale, collapsing of space or ambiguous spatial relationships, and a gestural use of line. In subject matter, freedmen art is characterized by an acute focus on self-presentation, specifically expressions of social mobility.

Gladatorial Combat, Amiternum, c. 50-1 B.C.E. (Museum, Aquila) (photo: Erin Taylor, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The pompa relief was part of an ensemble of reliefs—of which two remain—most likely inset into the fabric of a larger tomb complex that no longer survives. The other relief (above) depicts a scene of gladiatorial combat, an image type occasionally found on funerary monuments and usually understood as a reference to the public munificence of the deceased. Providing games or spectacles to the public was expected of magistrates and civil servants and such acts would be worthy of biographical commemoration. Though of servile families, freeborn men could and did rise to such offices. Considered together the two reliefs are mutually informing—displaying on the one hand, a spectacle for the public and, on the other, the spectacle of his death. As many ancient authors attest, the number of figures in a funeral procession directly correlated with the perceived importance of the deceased. While the patron of the Amiternum monument was not a member of the elite, patrician class, he certainly wanted to convey his importance by selecting two poignant images to document his biographical legacy—in recording public munificence during life and in expressing status in death.

The Tomb of the Haterii

Another tomb featuring a recognizable funerary ritual is that of the Haterii, built around 100 C.E. Discovered piecemeal in Rome since the late 1800s, the original form and layout of the tomb is unknown but the ambition of its decoration and narrative scope is obvious from the series of reliefs and portrait busts that do remain.

Mausoleum of the Haterii, c. 100 C.E. (Vatican Museums) (photo: Erin Taylor, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Constructed by a family of builders, the tomb simultaneously documents the death of the family matriarch and celebrates the family’s source of wealth. Though two busts remain of a male and female, it is the woman who appears multiple times in the visual program of the tomb’s reliefs. In the death scene, she appears on a funerary bed in the atrium of the house (above), surrounded by lit torches, a flute player at her feet, and her children beating their chests in mourning. Below the bed are three figures who wear the pileus, a cap of freedom worn by newly liberated slaves. This reference to the matron’s liberality and humanity is echoed both here with the figure reading her last will and testament beside her, as well as in another inset in which the deceased is shown making her will.

Mausoleum of the Haterii, c. 100 C.E. (Vatican Museums) (photo: Erin Taylor, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The viewer sees a conflation of time, viewing the deceased both alive and dead. In the relief above, she is shown in a retrospective portrait lounging on a couch with her children playing below. Under this vignette (below), is a grandiose temple-tomb with a portrait of deceased in the pediment and portraits of her children along the sides. In front of the tomb is a treadwheel crane which most scholars think is a reference to the family’s construction business.

Mausoleum of the Haterii, c. 100 C.E. (Vatican Museums) (photo: Erin Taylor, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Haterii were likely involved in important building projects during the reign of the Flavian emperors (69-96 C.E.), and another relief from the tomb probably documents some of their major projects in Rome including the Flavian Amphitheater (later known as the Colosseum) and the Arch of Titus.

Whether all of the reliefs originally constituted a narrative sequence or not is debatable but what does get communicated is the considerable expenditure on this tomb and the biographical means by which it was created. Though amassing considerable wealth, the Haterii family was, nonetheless, of servile origin.

Interpretation

Both the Amiternum relief and the Haterii tomb were commissioned by patrons outside of Roman elite society, a factor that had a huge impact on the style and narrative content of the monuments. Funerary art commissioned by the Roman elite almost never referenced commerce or sources of wealth though this was a driving goal for funerary art of the freedmen. Similarly, elite monuments do not document death rituals, though elites certainly observed them. The Amiternum relief and the Haterii tomb, however, rely on a narrative interplay between death ritual and biography. For these patrons, as for many freedmen and women, their final resting places provided an ideal opportunity for documenting ritual observance and, more importantly, for documenting their success in life and commerce.