Judaism is a monotheistic religion that emerged with the Israelites in the Eastern Mediterranean (Southern Levant) within the context of the Mesopotamian river valley civilizations. The Israelites were but one nomadic tribe from the area, so named because they considered themselves to be the descendants of Jacob, who changed his name to Israel.

The Levant (underlying map © Google)

Texts

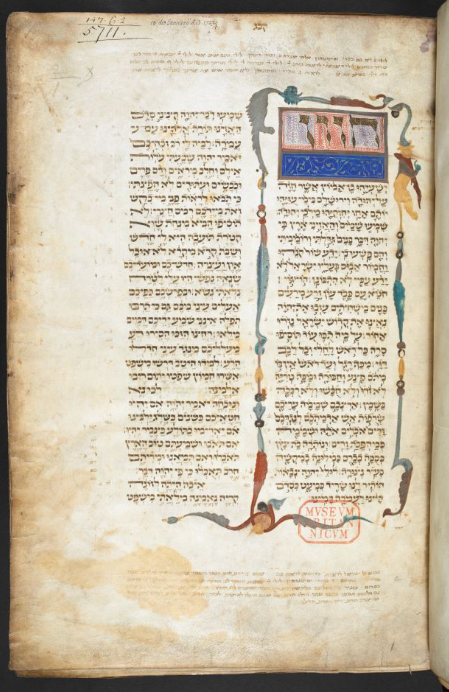

Judaism stems from a collection of stories that explain the origins of the “children of Israel” and the laws that their deity commanded of them. The stories explain how the Israelites came to settle, construct a Temple for their one God, and eventually establish a monarchy—as divinely instructed—in the ancient Land of Israel. Over centuries, the Israelites’ literature, history, and laws were compiled and edited into a series of texts, now often referred to as the Hebrew Bible (or Tanakh). Although the Hebrew Bible was compiled by the end of the first (or possibly second) century C.E., many of the stories it contains may be much older. The Hebrew Bible contains three major sections: the Torah (Five Books of Moses) the Prophets, and the Writings.

Hebrew Bible, Italy, 13th century, decorated opening to the Book of Isaiah, Harley 5711, f.1r. (The British Library)

An oral tradition emerged alongside the written Bible. Sometimes called the “Oral Torah,” the Mishnah is a minimalistic set of debates attributed to the great religious scholars, or Rabbis, transcribed and published in the second century C.E. The Rabbis’ intellectual descendants recorded and expounded upon the Mishnah in a series of writings called the Gemara and later generations compiled the Mishnah and Gemara into the Talmud.

Relief depicting a triumphal procession into Rome with loot from the temple, including the menorah, panel in the passageway, Arch of Titus, Rome, c. 81 C.E., marble, 6’–7” high (photo: Jebulon, CC0 1.0)

While the Hebrew Bible is Judaism’s most sacred text, many of the laws it delineates concern the practice of Temple sacrifice and priestly behavior. But when the Roman Emperor Titus sacked Jerusalem in response to a revolt of the Israelites in 70 C.E., his armies demolished the Temple of Jerusalem and brought the spoils back to Rome (an event recorded in a relief on the Arch of Titus in Rome, see image above). The loss of the Temple resulted in the end of ritual sacrifice and the priesthood; Judaism became a religion based on the interpretive discussions and practices that were eventually compiled into the Talmud. Sometimes, Judaism is referred to as “rabbinic Judaism,” since centuries of rabbinic interpretation, rather than the Bible, informs Jewish practice.

Judaism and time

Jewish law, called Halakhah, having been interpreted and re-interpreted over millennia, has changed over time. Even so, religious Judaism operates cyclically, and the linear way that modern historians view history does not correspond to this worldview. As historian Yosef Yerushalmi explained, the Rabbis “seem to play with time as though with an accordion, expanding and collapsing it at will.”[1] Major holidays, such as the weekly Sabbath or the annual Jewish New Year, provide a rhythm in order to structure a distinction between the sacred and the mundane. Other festivals rehearse ancient events, connecting modern Jews to the ancient Israelites. For instance, they mark the reception of the Torah at Mt. Sinai, the exodus from Egypt, the fall harvests, and the Maccabee victory over the Hellenistic Persian kingdom.

Isidor Kaufmann, Friday Evening, c. 1920, oil on canvas, 72.7 × 91.1 cm (The Jewish Museum, New York)

A collection of essays about Jewish cultures around the world opens with the phrase, “culture is the practice of everyday life.”[2] Judaism is a way of life that honors the cycle of days, weeks, months, years, and lives. Shabbat, the Sabbath, serves as the ultimate reminder of the Jewish cycle of time. Based on the idea that on the seventh day of Creation God rested, Shabbat is a marker of sacred time. Religious Jews refrain from all types of work on the Sabbath, and spend the day with their families and communities, praying, listening as a portion of the Torah is chanted (readings are determined by a fixed schedule), and eating luxurious meals. A great twentieth-century rabbi, Abraham Joshua Heschel, described the Sabbath as “a cathedral in time.”

The debate continues

Despite the authority of the rabbinic voice in the Talmud, Judaism is non-hierarchical. There is not—nor has there ever been—a single authority; the religion is embodied by a collection of learned voices, which often disagree. We tend to conceive of Judaism as an ancient religion—based out of the Levant where God gave the Israelites the Torah. But an essential piece of the religious tradition was the fact that rabbinical scholars continued to debate, discuss, and re-conceive ancient laws.

Torah Case, Iraq, 19th–early 20th century, silver overlaid on wood, with coral set cresting (The Jewish Museum, London)

Ancient tribal divisions, as well as later sectarian movements, including early Christianity, set a precedent for Jewish cultural diversity. But the religion is unified under the umbrella of the library of sacred texts, beginning with the Hebrew Bible, through the Talmud, and on to various ritual prayer books and mystical tracts. Judaism the religion, however, is distinct from the Jewish people. While it is clear that not all Jews practice Judaism, all those who practice Judaism consider themselves Jews. In other words, there are Jews without Judaism, but there can be no Judaism without Jews.

While the library and calendar unite Jews across the world, there are deep cultural and political divides. Jewish foods, music, literature, language, and interpretive practices vary immensely depending on a community’s ancestry. American Judaism, for example, is divided into movements, or denominations, much like American Christianity. These denominations have committees of rabbis who vote to determine the philosophy and types of observance their communities will uphold. But internal disputes are not only a standard feature of the denominations, they are part of the longstanding tradition of Jewish debate.

Notes:

[1] Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory (New York: Schocken Books, 1989).

[2] David Biale, Cultures of the Jews: A New History (Schocken, 2002).

Shrine to Mithras (Mithraeum), c. 240 C.E., painted plaster, 162.5 x 206.4 cm, today installed in the Yale University Art Gallery

On the frontier between east and west

The ancient site now known as Dura-Europos (in what is today Syria) was not a key site in antiquity if we only rely on preserved historical narratives in which it barely features. Rather, its importance is in its vast archaeological record, a record which we are still studying a century after excavations began. That record tells a complex picture about a diverse town which negotiated its place on the frontier between east and west, ending only when the site became a battlefield on which Roman and Sasanian armies clashed.

Dura-Europos has been destroyed many times. A Roman rampart built to protect the city in the third century C.E. failed, but luckily for us preserved beneath it are the extensive religious wall paintings for which the site is best known. In the twenty-first century, it has been destroyed again in the crossfire of the Syrian conflict, and by targeted antiquities looting. The extensive excavations conducted at the site over the past century nonetheless allow an important window into this ancient frontier town where a range of languages from Greek and Latin to Palmyrene Aramaic, Hebrew, and Safaitic, were written, and an even broader range of deities were worshipped.

Temple of Bel in 2005, Dura Europos, Syria (photo: Heretiq, CC BY-SA 2.5)

The site sits above the Euphrates river in Syria, a strategic location that was likely the reason for its founding in about 300 B.C.E. during the Hellenistic period. That initial settlement is not well known archaeologically, but was based on and around a citadel at the eastern edge of the site.

Site plan showing orthogonal (grid-planned) city blocks filling c. 52 hectares (128.5 acres) within the city walls and defended by steep cliffs on three sides. Plan by A. H. Detweiler, modified by J. Baird. Original used by kind permission of Yale University Art Gallery

Eventually it grew, with orthogonal (grid-planned) city blocks within the city walls and defended by steep cliffs on three sides. The long fortification wall on the western side of the site was pierced by a central gate dubbed the “Palmyrene Gate’”(indicated in the plan above) by its excavators, as it faced the steppe across which was Syria’s famous oasis city of Palmyra. A necropolis, consisting largely of chamber tombs, was preserved outside those city walls to the west.

Photo of House of Lysias, from North, in 1930s, showing central courtyard. Yale Dura Archive K327a

Early history under the Arsacids

For most of its history, from the late second/early first century B.C.E. until the late second century C.E., the site was held by the Arsacids (an eastern dynasty known to the Romans as the Parthians), but their power was indirect: it was wielded at Dura by a small number of local families. One family (the head of which held the title of strategos or general of the city), was the Lysiads—known not only from inscriptions but also from a large house associated with them that filled an entire city block (also indicated by block D1, near the right edge, in the plan above).

Painting of Conon and his family performing a sacrifice, installed for display in the Syrian National Museum in Damascus, from the ‘Temple of Bel’ in northwest corner of the city (Yale Dura Archive Dam157)

Painting of Conon and his family performing a sacrifice, installed for display in the Syrian National Museum in Damascus. From the ‘Temple of Bel’ in northwest corner of the city

Elite families are also depicted in paintings, such as that of Conon and his family performing a sacrifice, which was found in a temple in the northwest corner of the city known as the ‘Temple of Bel’. Under the Arsacids, the city was a regional capital where legal matters were handled, judging from civic records preserved on parchments at the site. The site also lay on important long-distance trade routes, which was perhaps the reason people from Palmyra were present at the site from at least the first century B.C.E.

The precise dates Dura was held by different powers are not known, despite having a great number of texts from the site, including inscriptions, parchments, and papyri which were recovered during excavations. This is in part because Dura was in a frontier zone of constantly shifting power.

Roman triumphal arch with Latin inscription found outside the city walls, reconstruction by Detweiler in 1937 (Yale Dura Archive Y594)

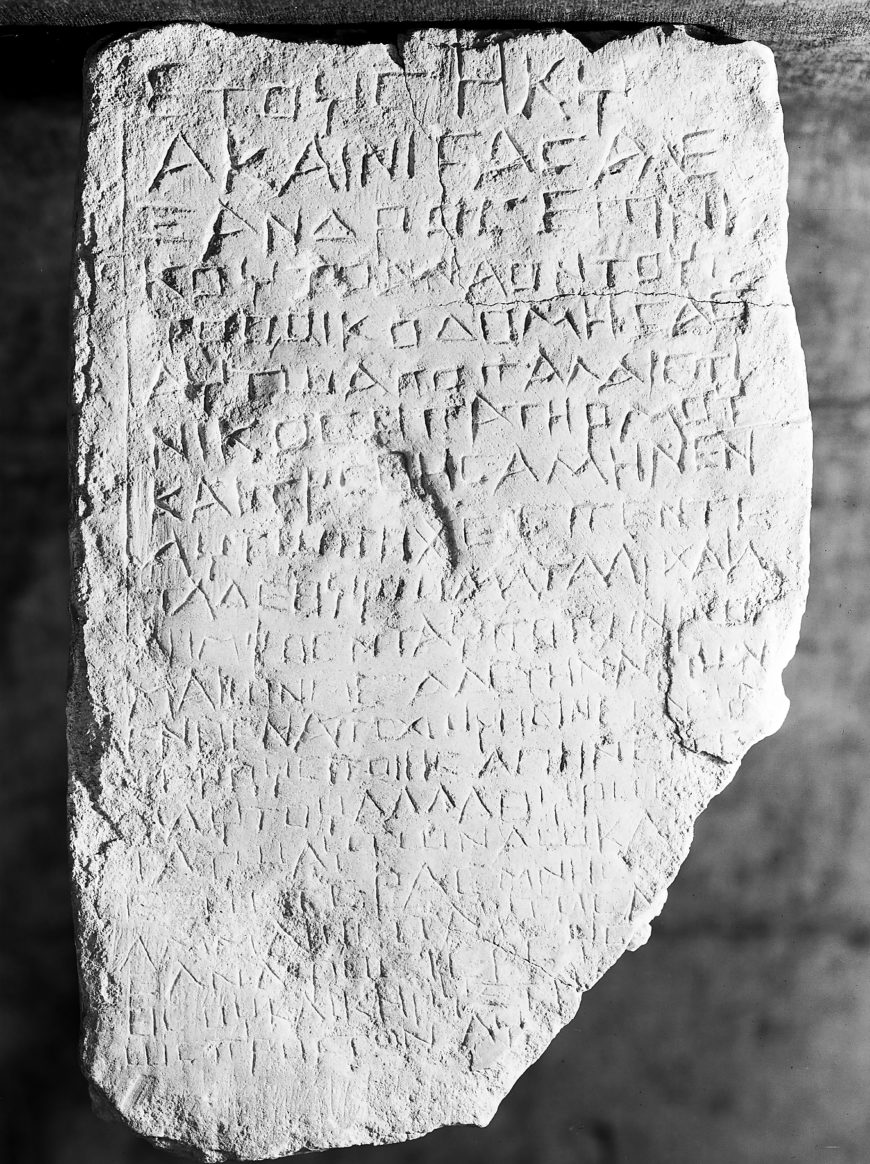

Greek Inscription recording renovation of religious building by Alexander, known also as Ammaios (Inscription no. 868, Photo Y466, Yale University Art Gallery)

The Romans

We know from inscriptions that the Romans under Trajan held the site, briefly, in the early second century, from a triumphal arch built outside the city (above), and from another inscription which belonged to a religious building (left). That inscription (dated c. 117 C.E.) records the restoration of a temple by a man known both by the Semitic name Ammaios and the Greek name Alexander, who held a position of priest. This restoration was needed because the doors of the building (presumably, made or decorated with something precious) had been “taken away by the Romans”, who had since departed the city. This practice of double-naming in which people from Dura have both Semitic and Greek names hints at the hybridity of the site, a characteristic that is also seen in its material culture.

Head of deity wearing a headdress, possibly Zeus Megistos, from the Temple of Zeus Megistos. Yale University Art Gallery 1938.5316

An earthquake in 160 C.E., recorded in a local inscription, is thought to have been the impetus for the building (and re-building) of a number of religious buildings in the second century. The sanctuaries are conventionally known by names assigned by the excavators (such as the ‘Temple of Zeus Megistos’ or ‘The Temple of Artemis’) but most of them preserved evidence for a range of deities. For instance, within the Temple of Zeus Megistos are found not only Zeus Megistos, but also the Palmyrene god Arsu and a nude hero, usually identified as Heracles or Nergal, who was popular at the site.

Left: Relief of the god Arsu, with Palmyrene Aramaic inscription reading “Arsu, the camel rider, ‘Ogâ, the sculptor made it for the life of his son”. Traces of black paint survive around the eyes, and the inscription was painted in red; the god is armed with a lance and shield. From the Temple of Zeus Megistos, Block C4 on the plan above(Yale University Art Gallery 1938.5311); right: Nude hero wrestling a lion, probably Heracles wrestling the Nemean lion. From the Temple of Zeus Megistos, Block C4 on the plan above (Yale University Art Gallery 1938.5302)

Interior of west end of Mithraeum during excavation, showing reliefs and paintings (Yale University Art Gallery, Dura-Europos Archive)

Within those sanctuaries were also found religious paintings, preserved best along the western side of the city beneath the Roman embankment, and sometimes “cult reliefs” (small inscribed reliefs dedicated to particular gods). Two such reliefs were found in the Mithraeum, a building dedicated to the god Mithras, whose cult spread widely during the Roman period, mostly among the military, particularly in the third century (see left and the top of this essay). People from Palmyra worshipped in the Mithraeum, and in other religious buildings at Dura, as we know from inscriptions which record their names and the names of their gods, often in Palmyrene Aramaic.

Late in the second century or early in the third, a Roman military garrison was installed within the city walls, taking over many existing buildings and constructing new ones on the north side of the site, including a Roman military palace, an amphitheatre, a principia (headquarters building), and baths. While this marked a major change at the site, and would have displaced many inhabitants, members of the Roman military did adapt to some local practices.

Painting from the ‘Temple of Bel’ of Julius Terentius and his men performing a sacrifice (Yale University Art Gallery, 1934.386)

For instance, a painting of the Roman tribune (cohort commander) Julius Terentius and his men performing a sacrifice was installed in the Temple of Bel, joining the earlier one of Conon and his family, and from a document on papyrus (such as divorce document P. Dura 32, 254 C.E.) we know of Roman soldiers who married local women.

View of the western wall of a model of the Dura-Europos Synagogue with narrative wall paintings and Torah shrine as it may have appeared between 244 and 256 C.E. The paintings are based on photographs taken prior to 1967. The model was created by Displaycraft in 1972 (collection of Yeshiva University Museum, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The earliest Christian house-church and a Jewish synagogue

The installation of the Roman garrison did not mark the end of life at the site, and some religious buildings were built and renovated during this period, including the Jewish synagogue with its extensive wall paintings (from the 2nd century), and a house which was adapted by the Christian community for use as a meeting place and baptistery (from the first half of the 3rd century), in which were preserved Christian paintings. This is the oldest preserved Christian house-church that is archaeologically known.

Latin inscription, painted on a wooden plaque, found in the Palmyrene gate, reading “To Septimius Lysias Strategos of Dura and the wife of the one mentioned above, Nathis, and their children Lysianius and Mecannaea, and Apollophanes and Thiridates, From the Beneficiarii and Decurions of the Cohort,” 3rd century C.E. (Yale University Art Gallery, 1929.370)

Elite families also held on to power, at least for a while, and negotiated their place under Roman rule by, for example, taking Roman names in addition to their other names and titles. In one inscription painted on a wooden plaque found at the Palmyrene gate, it notes one “Septimius Lysias Strategos of Dura,” with Septimius as the added Roman name. Formal inscriptions, usually carved in stone rather than painted on wood, are found in Greek, Latin, and Palmyrene Aramaic throughout the site.

Graffito from Strategion palace (Block C9 on the plan above) of mounted lancer and deer (Yale Dura Archive D200)

On walls throughout Dura, hundreds of graffiti were found, ranging from simple scratched images of camel caravans to elaborate urban landscapes, and preserving lists, receipts, calendars, horoscopes, and many names. These occurred on fortifications in busy parts of the city like the Palmyrene gate but also house walls and within religious buildings and were not illicit markings in the way we think of graffiti today.

Satellite imagery before (top) and after episodes of heavy looting (bottom), leaving the surface of the site covered in round depressions resembling a moonscape (retrieved from Google Earth)

The end of Dura-Europos as an urban settlement

The end of the site as an urban settlement and military garrison came c. 256 C.E. when the Sasanians captured it, after a siege, known from the preserved remains of a siege ramp, mines, and countermines, as well as military equipment. The walls of the site still stood though, and indeed were still standing in the 20th century for it to be discovered. Those same walls stand today, but since the start of the Syrian conflict (2011–present) the site has become, again, a place of conflict. The most notable aspect of this is the systematic looting of the site for antiquities which could be trafficked onto the antiquities market. Satellite photos show the extent of the damage, with the surface of the site covered in the holes made by looters.

Despite the looting at the site, the new destruction has not erased the past of this ancient Syrian city, and much remains to be learned. The extensive excavations tell a story not only of successive empires but also of the resilience of daily life during those times, for instance in the continuity of the mudbrick and plaster courtyard houses which characterized the site. With the extensive archaeological archive which survives from the excavations of the 1920s and 30s we can continue to investigate this multicultural and polyglot ancient site.

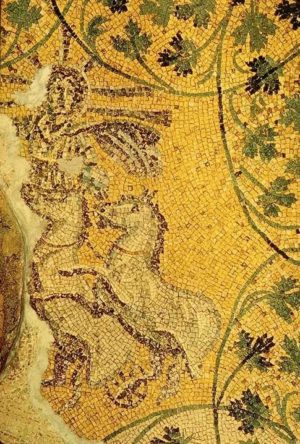

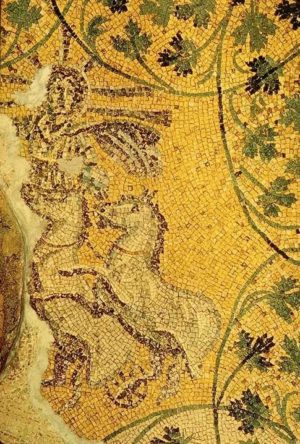

Tiny cube-shaped pieces of cut stone and glass combine to form a mosaic image of a god, a beautiful young male with curly hair and a radiant crown of seven rays of light. He raises his right hand as if signaling his mastery of the cosmos. In his left hand, he holds an orb (representing the sun) and a whip to urge his horses forward. He once stood in a quadriga, a chariot pulled by four horses, now destroyed by the later addition of a wall, though their hooves can still be seen. This 4th-century mosaic depicts the indomitable Roman sun god Sol, known in Greek as Helios.

Sol and empire

Sol became an especially popular solar deity in the later Roman Empire. There was a long imperial tradition of worshiping the sun god, and by the 3rd century, emperors frequently associated themselves with Sol, referring to the god with the epithet “Invictus,” meaning invincible. As the Roman emperors expanded their territory and defended their borders, the sun god’s attributes of eternity and dominion proved an irresistible model for representing imperial triumph. As a result, the image of Sol Invictus frequently appeared in imperial coinage and monuments.

The early fourth-century emperor Constantine I was a particularly fervent adherent of the cult of the sun. Nearly three-quarters of his coinage included portraits of himself with Sol’s rayed crown and raised right hand, and the inscription SOLI INVICTO COMITI (to the invincible sun, companion [of the emperor]).Roman coin of Constantine I with Sol Invictus on the reverse, 307–318 C.E. (Anja Rohde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

However, this mosaic image of Sol does not adorn an imperial monument, or even a Roman temple or bath; rather it is found at the center of an ancient synagogue floor, a Jewish house of worship in Hammath Tiberias in the Roman-controlled territories of northern Israel.

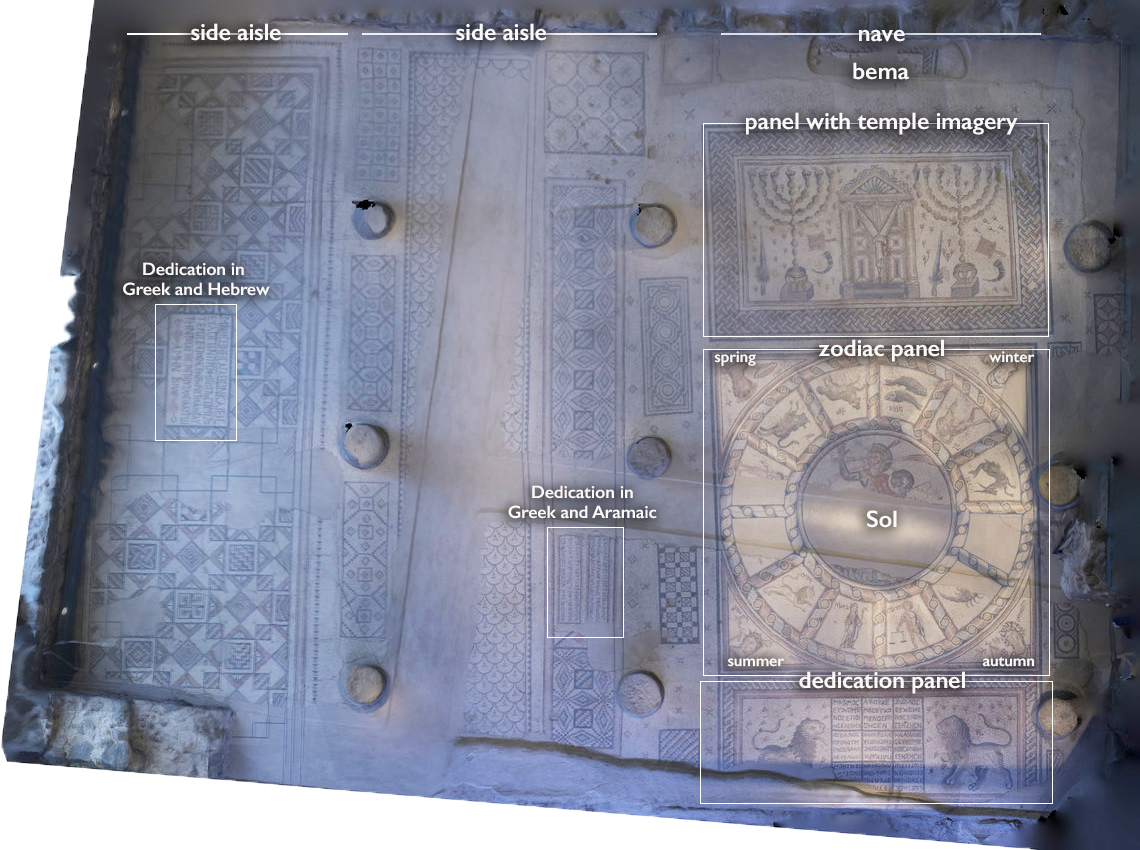

In Hammath Tiberias, the personified sun god appears at the center of a large mosaic floor divided into three panels featuring dedicatory inscriptions, personifications of the seasons and the twelve signs of the zodiac, and motifs associated with the ancient Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. What prompted the fourth-century Jewish community of Hammath Tiberias, a monotheistic community, to adorn their house of worship with an image of Sol, a prominent Roman deity? The mosaics of Hammath Tiberias can only be understood in the context of Late Antique and early Byzantine Jewish history and culture, Greco-Roman and early Christian artistic traditions, and the dramatic political, religious, and social circumstances of the 4th through 7th centuries.

Judea in the Roman Empire, 117 CE (underlying map © Google)

Roman expansion and religious pluralism in the eastern Mediterranean

From the early days of the Roman Republic on, the Romans continuously expanded their territory as they came into conflict with surrounding city-states, kingdoms, and empires. By the second century C.E., the Roman Empire had reached its greatest extent, with its territory stretching across modern-day western Europe, north Africa, and western and central Asia. Judea (the Land of Israel) was among the many new regions conquered by the Romans, including the city of Tiberias, founded by Roman Emperor Herod Antipas in 19–20 C.E. on the fertile shores of the Sea of Galilee. To its south lies a small suburb, Hammath Tiberias, well known for its therapeutic baths fed by natural hot springs.

As the Romans conquered Judea and other territories, for the most part, these new cities and regions were allowed to maintain their existing cultural and political institutions. Although religious practice of the Roman Empire centered on the pantheon of Roman gods, the Jewish communities living in the Roman-controlled Judea and in the Diaspora were permitted freedom of religious worship. This likewise extended to other religious communities, such as Zoroastrians, and Christians, among others, living in the territories of the Roman Empire.

Having lived under Roman rule from at least the 2nd century B.C.E., the Jewish population had acculturated and developed a deep knowledge and appreciation of Greco-Roman traditions and artistic forms. Alongside reading Hebrew, the language of the Hebrew Bible, and speaking and writing in Aramaic, the literary and spoken language of the Jewish community in the land of Israel, many Jews also spoke and wrote in Greek, widely used throughout the Roman Empire.

Beginning in the 4th century, the Eastern Mediterranean underwent a period of dramatic political, economic, and cultural change, including the rapid Christianization of the region. As the religious majority changed, Jews and Christians lived side by side, in dialogue and in competition. This was especially the case in their artistic output. Jews and Christians drew upon a common visual language that emerged out of the dominant Roman visual tradition. Although they shared art forms, materials, and techniques, they adapted these elements to express their own theologies and histories. For example, clay oil lamps dating to the 2nd through 4th centuries reflect this shared heritage—some oil lamps display Roman deities, such as the sun god Sol, while others include Christian symbols such as the chi-rho, or Jewish symbols, such as the menorah. As much as artistic production reflected their collective cultural experience, it also became an indispensable tool for each religious community to define itself vis-a-vis the other.

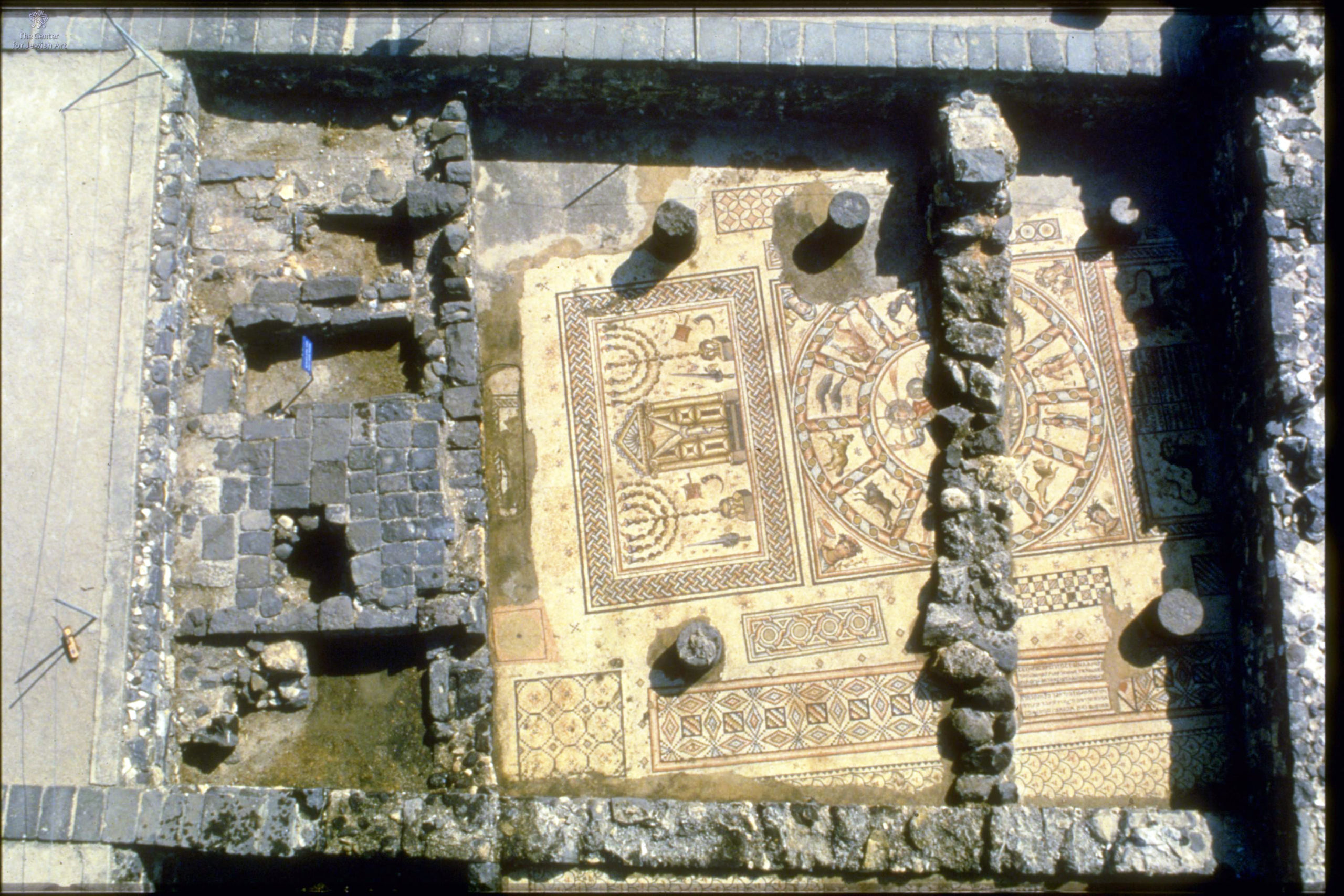

Hammath Tiberias synagogue, 286–337 C.E., Israel (Brad Erickson, CC BY-NC 4.0)

The Hammath Tiberias mosaics

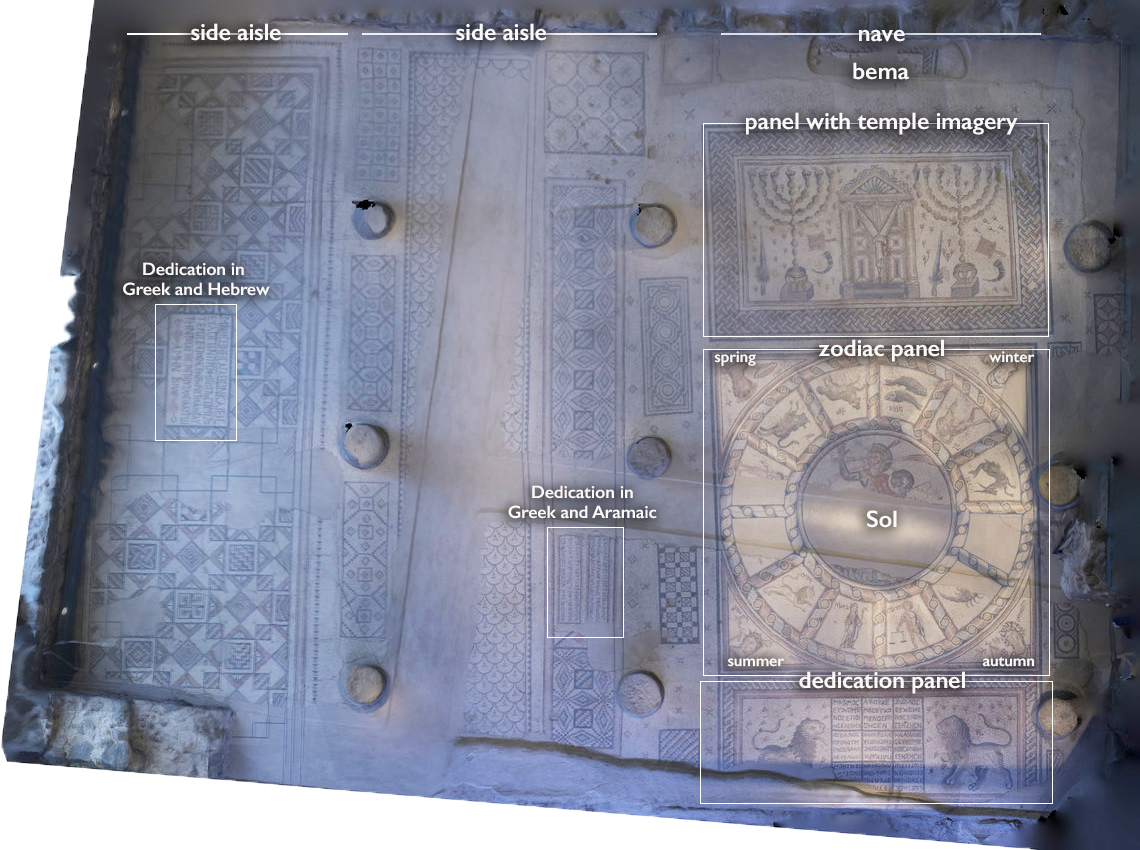

Located on a bluff overlooking the Sea of Galilee, the Hammath Tiberias synagogue was built in the first half of the 3rd century following a basilica plan with a central nave and two side aisles, a layout commonly used for Roman public buildings. Following its partial destruction by an earthquake in 306 C.E., the local residents renovated the synagogue, retaining much of its original structure, while also outfitting it with a new mosaic floor.

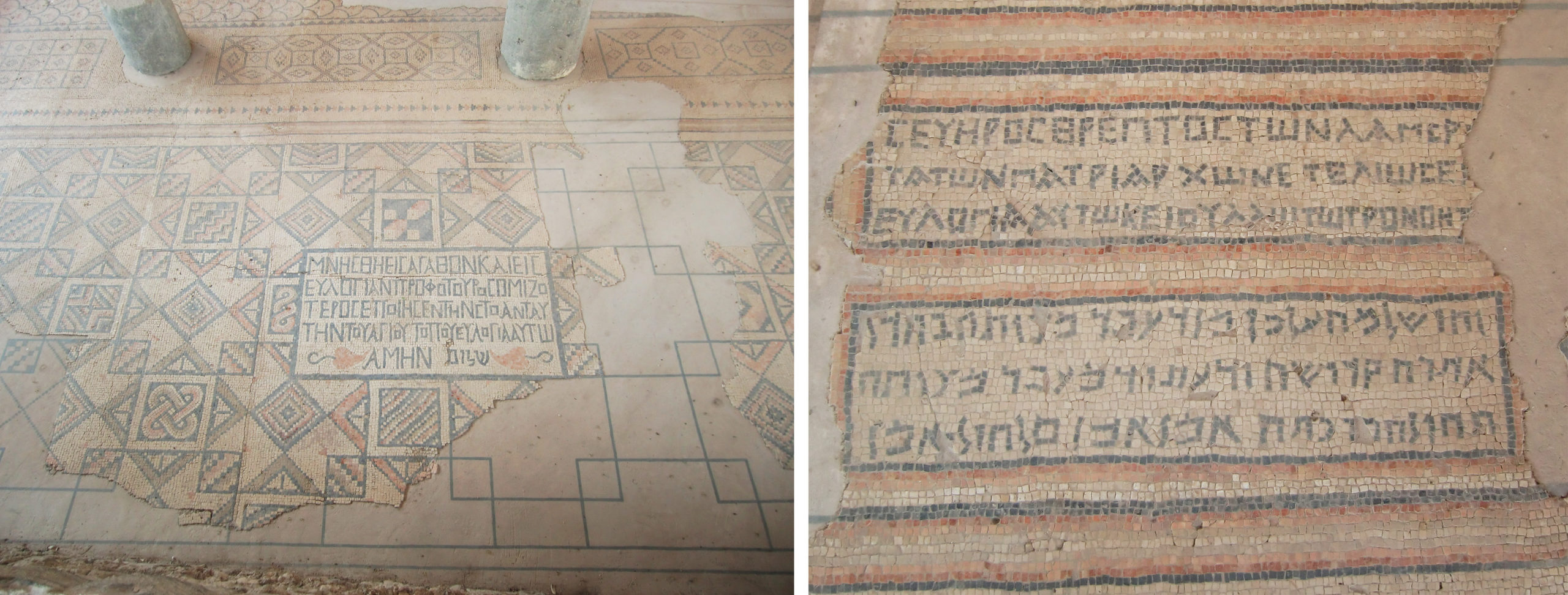

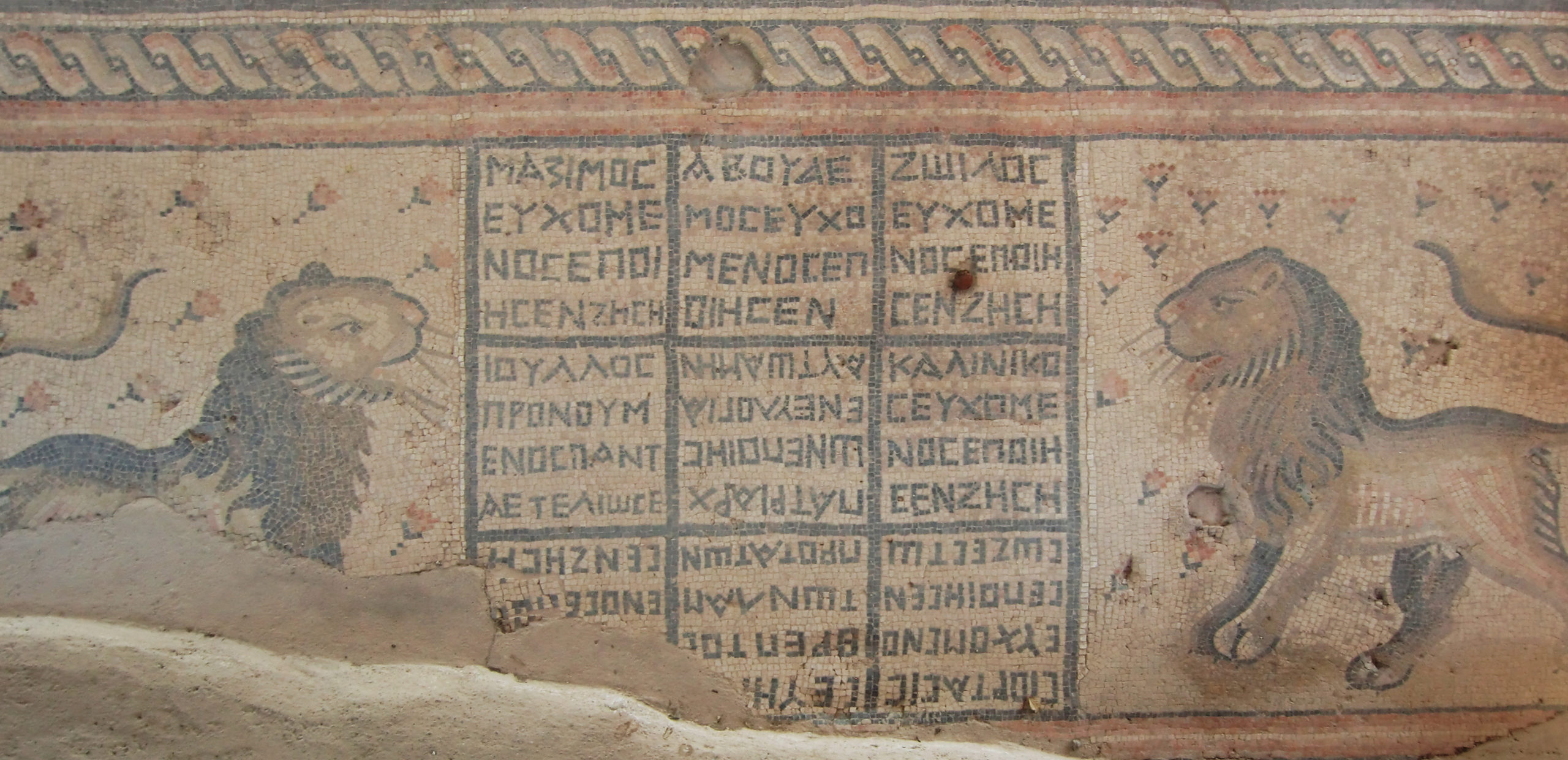

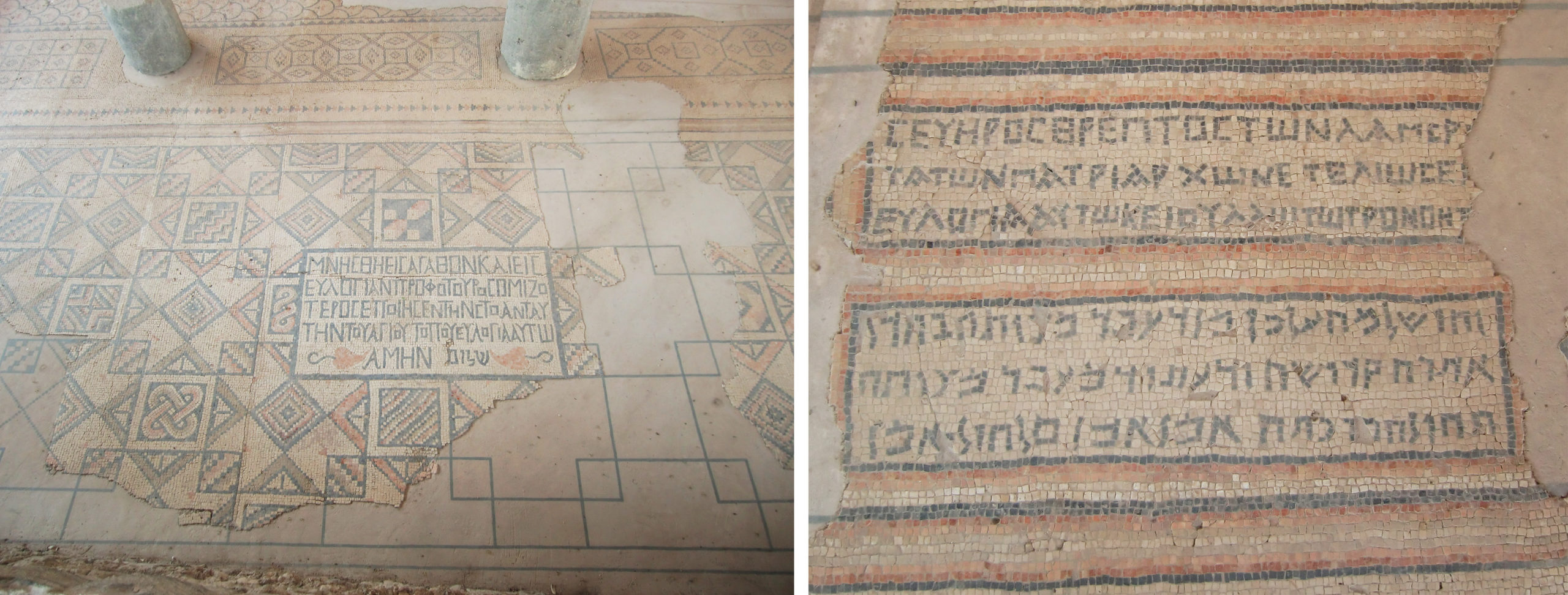

Left: Greek dedicatory inscription; right: Greek and Aramaic dedicatory inscriptions, side aisles, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (Manar al Athar)

Upon entering from the east, worshippers encountered three dedicatory inscriptions, two in Greek and one in Aramaic naming the synagogue’s main donors and blessing other members of the community who had or would donate to the synagogue. Several inscriptions mention “Severos, student of the illustrious patriarch,” suggesting that the synagogue may have been closely aligned with the Patriarchate, which acted as the official channel of communication between the Roman Empire and its Jewish subjects. With their ties to the patriarch, the reconstruction and lavish decoration of the synagogue would have offered Severos and other local elites the opportunity to communicate their wealth, power, and distinctly Jewish identity to a broader public.

Panel with Greek dedicatory inscriptions, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (Manar al Athar)

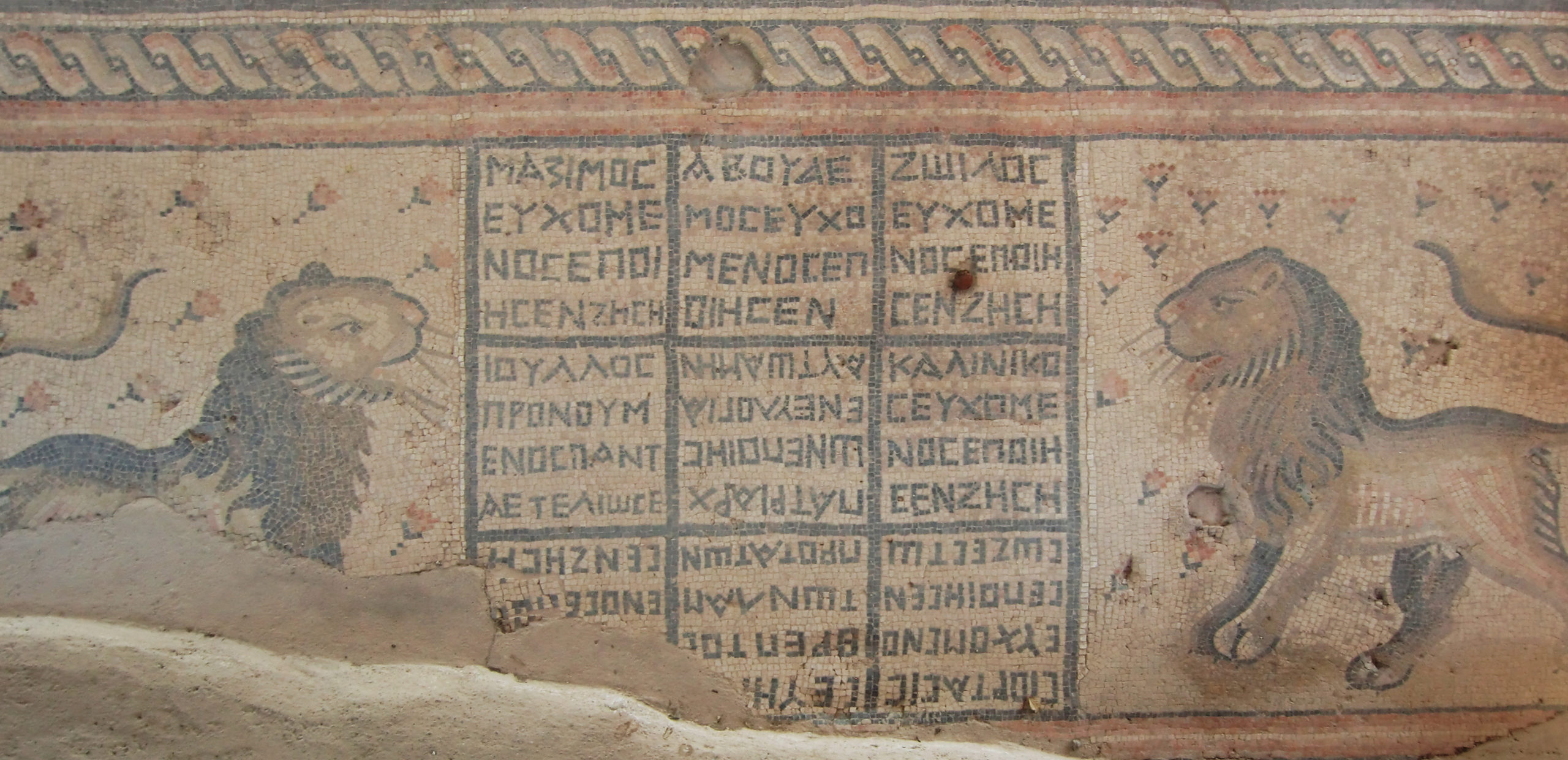

The mosaics of the side aisles, although mostly destroyed, contained continuous geometric patterns and dedicatory panels. In contrast, the mosaics of the nave are divided into three panels featuring figural imagery. To the north, a pair of mosaic lions flank a dedicatory panel, divided into nine squares and inscribed in Greek with the names of the synagogue’s donors, including two squares devoted to the patronage of Severos.

Personifications of the four seasons, zodiac, and Sol, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (fabcom)

Personification of Autumn, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (Manar al Athar)

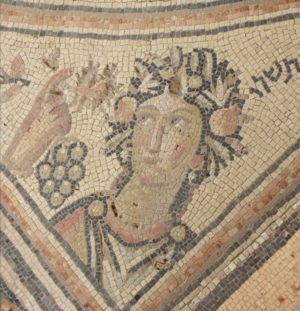

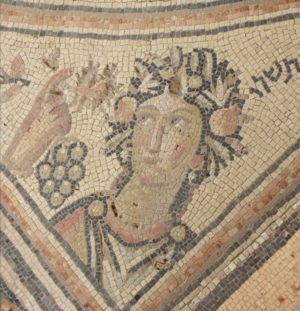

The center of the room features a large panel with personifications of the seasons labeled in Hebrew in each of its four corners. Each of the personifications bears attributes representing the agricultural activities of the season: Spring for example wears a sleeveless tunic, a wreath of flowers, and carries a bowl of flower buds; Autumn wears a wreath of leaves with figs and pomegranates and carries a vine branch with grapes and possibly olives, symbolizing the fall harvest.

These personifications frame two concentric circles that contain images of the twelve astrological signs of the zodiac in the outer circle, also labeled in Hebrew, with the sun god Sol in the inner circle. Like Sol, the form of the zodiac and its individual figures draw on contemporary Roman artistic traditions. The astrological sign for Virgo, for example, appears similar to the goddess Kore-Persephone, whose cult was popular in Roman Israel.

Mosaic panel with Temple imagery, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (Manar al-Athar)

At the southern end of the synagogue, a bema (raised platform) with a Torah ark (an architectural shrine housing the Torah scrolls), demarcated the sacred locus of the synagogue. Just before the bema, is a mosaic image of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem. At its center is an architectural façade, with two wooden doors covered by a curtain (the parochet, the curtain described in the Hebrew Bible as hanging before the Ark of the Covenant). It is flanked by two large menorot, or seven-branched candelabras, as well as smaller depictions of the lulav and etrog, shofar, and incense shovels—all objects derived from the rituals of the ancient Temple.

Detail of personifications of the four seasons, zodiac, and Sol, Tzippori synagogue, Galilee, 5th century C.E. (Manar al-Athar)

The mosaic floors, with their combination of Jewish religious imagery and motifs adapted from Greco-Roman traditions, powerfully evoked the sacred atmosphere of the ancient synagogue. While the mosaics at Hammath Tiberias are the first known instance of this iconography, this composition, with its imagery of the ancient Temple and vision of sacred time, clearly presented a compelling message for the Jewish community. Variations with the zodiac, temple implements, and biblical scenes, which further emphasize God’s covenant with the Jewish people, appear in five later extant synagogue floors across northern Israel, all dating to the 5th and 6th centuries: Beth Alpha, Huseifa, Susiya, Na’aran, and Tzippori.

Sol or God the Creator?

View of the western wall of a model of the Dura-Europos Synagogue with view of its narrative wall paintings and Torah shrine as it may have appeared between 244 and 256 C.E. The paintings are based on photographs taken prior to 1967. The model was created by Displaycraft in 1972 (collection of Yeshiva University Museum, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Since its discovery in 1961, the Hammath Tiberias mosaics have drawn significant attention. On the one hand, these images defy the widely held assumption that Judaism is a non-visual tradition, either not producing visual art at all or creating only non-figural images, due to the Second Commandment prohibition against the creation of graven images. The Hammath Tiberias mosaics, along with the discovery of several other ancient synagogue floors filled with figural imagery and the extensive figural paintings of the contemporaneous Dura-Europos synagogue in Syria, emphatically dispel this notion.

During the late Roman and early Byzantine periods in which the synagogue mosaics were produced, through to the present day, Jewish communities have interpreted the Second Commandment liberally, not considering figural images to be idolatrous. Nevertheless, the question remains, how did the Jewish community of Hammath Tiberias reconcile their Jewish faith with the personification of the sun god Sol at the center of their most sacred space?

Mosaic with Sol, Luna, Aion, and the four seasons, House of Silenus, Thysdrus (Tunisia), late 3rd–early 4th century C.E. (Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

No singular interpretation can fully explain the figure of Sol in Hammath Tiberias and other Galilean synagogues; however, the range of possibilities reflect the complexity of Jewish communal life in late antiquity. Some interpretations understand Sol at Hammath Tiberias as nothing more than an image of the sun. Although Sol is a god, Sol differs from almost all other Roman gods; after all, the sun is a natural, visible phenomenon. So, while some images represented Sol as a god in a traditional sense, including in cult statues and depictions of mythological scenes, Sol also appeared as a representation of the sun and the heavens. For example, a mosaic floor from the house of Silenus in Thysdrus (modern-day Tunisia), includes busts of Sol, Luna (personification of the moon), and Aion, a Roman deity associated with cyclical time, alongside personifications of the four seasons. Shown together, they evoke the heavens and the annual passage of time. According to this interpretation, the mosaic image of Sol at Hammath Tiberias, along with the surrounding moon and stars, and the figures of the zodiac, may depict the Jewish heavens or a calendar, taking part in a complex visualization of the Jewish cycle of sacred time.

On the other hand, it is possible that the representation of Sol may in fact reflect the actual worship of the cult of the Sun God in Jewish circles in the 3rd century. By this time, sun worship, focusing on the Roman deity Sol, was embedded in Roman religious practices. At the same time as the cult of the sun took center stage amongst the Roman polytheistic population, Jewish laws composed and compiled by the rabbis reflected a real fear that Jews would worship the sun and moon. A Jewish magic book from the late 3rd or early 4th century, for example, includes a prayer in honor of Helios (the Greek name for Sol). Perhaps the synagogue floor mosaics represent an aspect of popular Jewish worship, practiced by Greek-speaking Jews who were familiar with local cult practices.

Temple and Zodiac panel with Sol, Hammath Tiberias, 286–337 C.E. (Manar al-Athar)

More likely, rather than evidence of Jewish sun worship, the synagogue’s mosaics (both the figure of Sol as well as the imagery of the zodiac), suggest the level of acculturation of the Jewish community to their Roman neighbors. Having lived under Roman rule for centuries, Jews were intimately familiar with the institutions of Roman life. They borrowed and adapted the visual formulae used in Roman art and architecture within their own constructions. First and foremost, the patrons of the Hammath Tiberias Synagogue decorated their holy space with mosaics—a ubiquitous medium throughout the Roman Empire, found in bathhouses, marketplaces, temples, churches, and private homes, meant to impress and convey wealth and prestige.

Triumph of Neptune, Roman mosaic from La Chebba, Tunisia, late 2nd century C.E. (Tony Hisgett, CC BY 2.0)

Moreover, in the selection of geometric and figural imagery, the Hammath Tiberias floors drew heavily upon the local Roman and the later Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire’s mosaic repertoires. For example, a comparable image of Sol leading his chariot through the universe can be seen in a mosaic from a 3rd-century Roman villa, as well as representations of other deities ruling from their chariots, such as the god Neptune in a late 2nd-century mosaic from La Chebba (modern-day Tunisia).

In the Hammath Tiberias floors, the representation of the sun god may have been conceived of as a Judaized Sol Invictus—the Jewish god as the single, invincible ruler of the universe. The purple color of the young god’s tunic and his globe are reminiscent of Roman imperial images. Moreover, Jewish sources in late antiquity referred to God’s supremacy by connecting his power with symbols of authority, such as riding a horse or chariot. By adapting this imperial motif of Sol Invictus, the synagogue floor conveyed the God of Israel’s absolute power over the universe—the land and sea from which the chariot emerges—and all of time, captured in the surrounding zodiac.

Visualizing time

For the Jewish community worshiping within the Hammath Tiberias synagogue, the images of the mosaic floor, combined with the synagogue’s furnishings, may have offered a vision of Jewish time—past, present, and a hope for a messianic future. The synagogue’s representation of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem, depicted the Jewish past. During the The First Jewish-Roman War, in which the Jewish population rebelled against the Romans, the Roman army laid siege to the city of Jerusalem, destroying the Temple and leaving the Jewish people without a religious center to bind them together. Over time, new institutions and leaders arose to fill that void. Synagogues offered new spaces where the Jewish community could gather to read the Hebrew Bible, pray, and form a sacred community with their God.

Left: Menorah from a second synagogue in the town of Hammath Tiberias, known as Hammath Tiberias A, 5th–6th century C.E., limestone (Israel Museum); right: Torah Ark lintel, Nabratein synagogue, 3rd century C.E. (Davidbena, CC BY 4.0)

The Hammath Tiberias mosaics representing the ancient Temple appeared just before the part of the synagogue where the the Torah shrine was located. Although few Torah shrines have survived intact, a stone lintel of a Torah shrine from a 6th-century synagogue in the Jewish village of Neburaya in the upper Galilee, gives us a sense of what the original shrine in the Hammath Tiberias Synagogue would have looked like. Its arched form closely resembles Hammath Tiberias’s mosaic image of the ancient Ark of the Covenant. Moreover, just as in the mosaic floor, Hammath Tiberias’s Torah shrine likely would have been flanked by two seven-branched stone menorahs, like the menorah uncovered at a 5th- or 6th-century synagogue in the same town. Framed by stone candelabras, the near mirror image between the Hammath Tiberias mosaic floor and its furnishings would have reflected an attempt to associate the synagogue with the ancient Temple, as both descending from and replacing the now-obsolete Temple rituals. The mosaic may have also symbolically signaled a longing for the future rebuilding of the Temple and the restoration of its cult practices. According to Jewish tradition, with the coming of a messiah, the temple will be rebuilt and its rituals restored. Thus, the Temple panel and the synagogue’s bema visualized past, present, and future Jewish worship.

This concept of time is anchored in the imagery at the center of the synagogue—the four seasons, the zodiac, and the sun (Sol), moon, and stars. Together they presented a Jewish vision of daily, monthly, and annual cycles of time, offering a multilayered affirmation of God’s covenant with the Jewish people throughout history. Such themes would have been especially appropriate for the Jewish community living under Roman rule. It would have emphasized the legitimacy of Jewish monotheistic tradition in the face of the polytheistic Roman cults.

By the 5th century, this imagery became even more relevant, as the Jewish community faced a rising threat—Christianity. These two monotheistic religions had rival claims to a covenant with God. While both sought their foundations in the text of the Hebrew Bible, Christianity conceived of Judaism as a tradition it had superseded. For Christian readers, Hebrew scriptures recount the history and prophecies of God’s original chosen people and foreshadow God’s new covenant with the Christian people.

Mosaic with Helios (Sol) and Selene (goddess of the moon) and the labors of the month, Monastery of Lady Mary, Scythopolis, 6th century, watercolor by A. Bentwich (Penn Museum)

Christ as Sol Invictus, 3rd–4th century C.E., Tomb of the Julii (Mausoleum M), Vatican Necropolis (Tablar)

With their competing universal claims, the Jewish and Christian communities looked to the same visual language to express their legitimacy. Just as at Hammath Tiberias, Christian patrons transformed Jesus into the solar emperor of the universe, Sol Invictus. In a mausoleum beneath St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, for example, we see a possible Christianized Sol Invictus, a figure bearing a cross-shaped nimbus riding on a chariot with a sunburst halo. Similarly, the 6th-century monastery of Scythopolis (Beth Shean) in the Galilee also includes a floor mosaic of the zodiac with Sol and a personification of the moon at its center. As the new Christian religion developed, gaining imperial support and followers, the Jewish community needed to define and defend their own legitimacy as inheritors of God’s promise to the Jewish people. By visually staking a claim to the Jerusalem Temple and God’s covenant, and using Sol Invictus as a symbol of the Jewish God’s infinite powers, they declared that the messiah described in Christian doctrine had not yet come, emphasizing that the Jews, and not the Christians, are the chosen people of the Hebrew Bible.