Beautifully preserved life-size painted limestone funerary sculptures of Prince Rahotep and his wife Nofret. Note the lifelike eyes of inlaid rock crystal (Meidum, Old Kingdom) (Egyptian Museum, Cairo; photo: Panegyrics of Granovetter, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Appreciating and understanding ancient Egyptian art

Ancient Egyptian art must be viewed from the standpoint of the ancient Egyptians to understand it. The somewhat static, usually formal, strangely abstract, and often blocky nature of much Egyptian imagery has, at times, led to unfavorable comparisons with later, and much more “naturalistic,” Greek or Renaissance art. However, the art of the Egyptians served a vastly different purpose than that of these later cultures.

Art not meant to be seen

While today we marvel at the glittering treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamun, the sublime reliefs in New Kingdom tombs, and the serene beauty of Old Kingdom statuary, it is imperative to remember that the majority of these works were never intended to be seen—that was simply not their purpose.

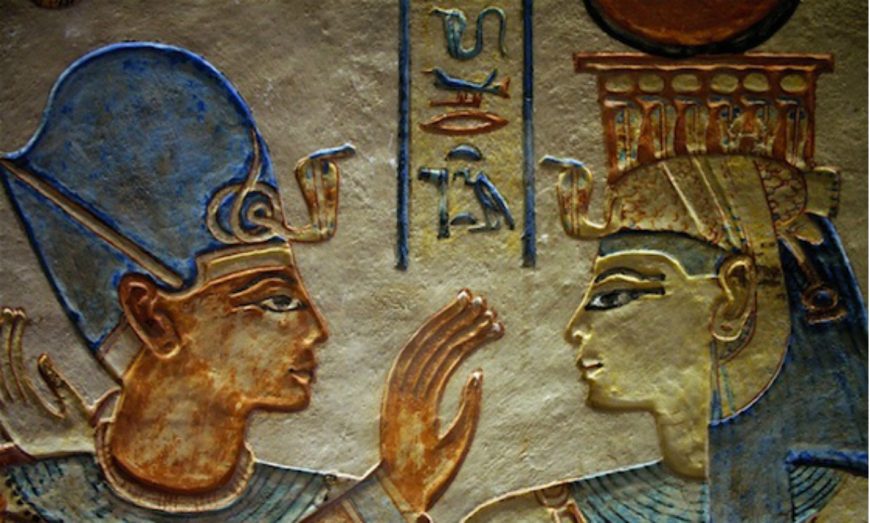

Painted sunk relief of the king being embraced by a goddess. Tomb of Amenherkhepshef (QV 55) (New Kingdom, Ramesside) (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

The function of Egyptian art

These images, whether statues or reliefs, were designed to benefit a divine or deceased recipient. Statuary provided a place for the recipient to manifest and receive the benefit of ritual action. Most statues show a formal frontality, meaning they are arranged straight ahead, because they were designed to face the ritual being performed before them. Many statues were also originally placed in recessed niches or other architectural settings—contexts that would make frontality their expected and natural mode.

Statuary, whether divine, royal, or elite, provided a kind of conduit for the spirit (or ka) of that being to interact with the terrestrial realm. Divine cult statues (few of which survive) were the subject of daily rituals of clothing, anointing, and perfuming with incense and were carried in processions for special festivals so that the people could “see” them—they were almost all entirely shrouded from view, but their “presence” would have been felt.

Royal and elite statuary served as intermediaries between the people and the gods. Family chapels with the statuary of a deceased forefather could serve as a sort of “family temple.” There were festivals in honor of the dead, where the family would come and eat in the chapel, offering food for the Afterlife, flowers (symbols of rebirth), and incense (the scent of which was considered divine). Preserved letters let us know that the deceased was actively petitioned for their assistance, both in this world and the next.

What we see in museums

Generally, the works we see on display in museums were products of royal or elite workshops; these pieces fit best with our modern aesthetic and ideas of beauty. Most museum basements, however, are packed with hundreds (even thousands!) of other objects made for people of lower status—small statuary, amulets, coffins, and stelae (similar to modern tombstones) that are completely recognizable, but rarely displayed. These pieces generally show less quality in the workmanship; sometimes being oddly proportioned or poorly executed, they are less often considered “art” in the modern sense. However, these objects served the exact same function of providing benefit to their owners, and to the same degree of effectiveness, as those made for the elite.

Hard stone group statue of Ramses II with Osiris, Isis, and Horus (New Kingdom). (Egyptian Museum, Cairo; photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Modes of representation for three-dimensional art

Three-dimensional representations, while being quite formal, also aimed to reproduce the real-world—statuary of gods, royalty, and the elite was designed to convey an idealized version of that individual. Some aspects of ‘naturalism’ were dictated by the material. Stone statuary was quite closed, with arms held close to the sides, limited positions, a strong back pillar that provided support, and with the fill spaces left between limbs.

Model scene of workers ploughing a field, Middle Kingdom, late Dynasty 11, 2010–1961 B.C.E., painted wood, 54 cm (MFA Boston)

Wood and metal statuary, in contrast, was more expressive—arms could be extended and hold separate objects, spaces between the limbs were opened to create a more realistic appearance, and more positions were possible. Stone, wood, and metal statuary of elite figures, however, all served the same functions and retained the same type of formalization and frontality. Only statuettes of lower-status people displayed a wide range of possible actions, and these pieces were often focused on the actions which benefited the elite owner, not the people involved.

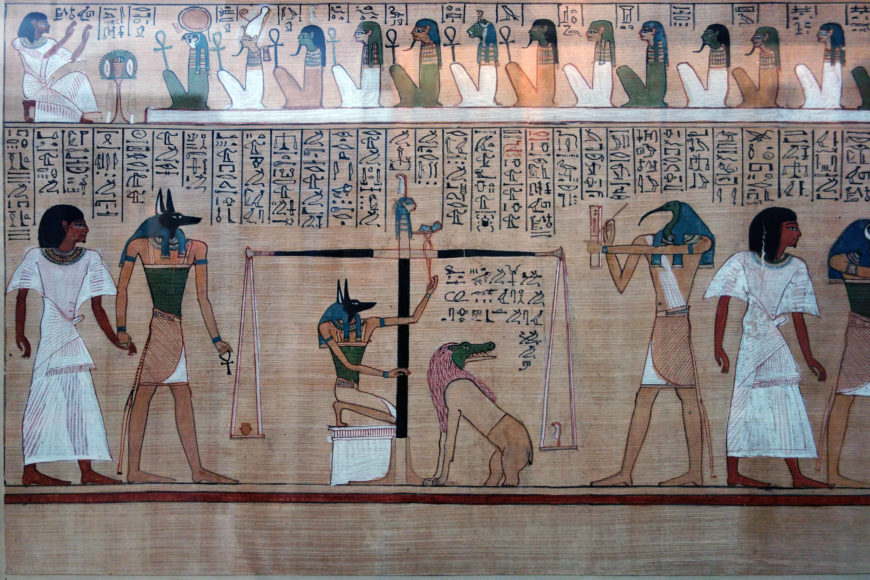

Detail of Hunefer’s Book of the Dead showing an upper and lower register. Hunefer’s Judgement in the presence of Osiris, Book of the Dead, 19th Dynasty, New Kingdom, c. 1275 B.C.E., papyrus, Thebes, Egypt (British Museum; photo: Steven Zucker; CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Modes of representation for two-dimensional art

Two-dimensional art was quite different in the way the world was represented. Egyptian artists embraced two-dimensionality and attempted to provide the most representational aspects of each element in the scenes rather than attempting to create vistas that replicated the real world.

Each object or element in a scene was rendered from its most recognizable angle, and these were then grouped together to create the whole. This is why images of people show their face, waist, and limbs in profile, but eye and shoulders frontally. These scenes are complex composite images that provide complete information about the various elements, rather than ones designed from a single viewpoint, which would not be as comprehensive in the data they conveyed.

Registers

Chaotic fighting scene on a painted box from the tomb of Tutankhamen (New Kingdom). (Egyptian Museum, Cairo; photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Scenes were ordered in parallel lines, known as registers. These registers separate the scene as well as provide ground lines for the figures. Scenes without registers are unusual and were generally only used to specifically evoke chaos; battle and hunting scenes will often show the prey or foreign armies without groundlines. Registers were also used to convey information about the scenes—the higher up in the scene, the higher the status; overlapping figures imply that the ones underneath are further away, as are those elements that are higher within the register.

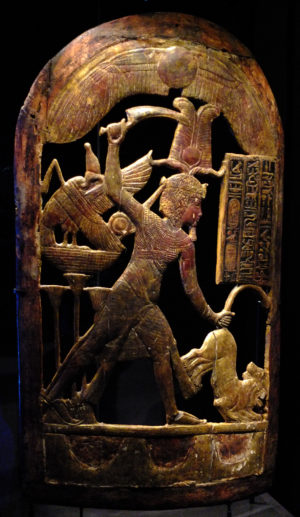

Hierarchy of scale

Difference in scale was the most commonly used method for conveying hierarchy—the larger the scale of the figure, the more important they were. Kings were often shown at the same scale as deities, but both are shown larger than the elite and far larger than the average Egyptian.

Text and image

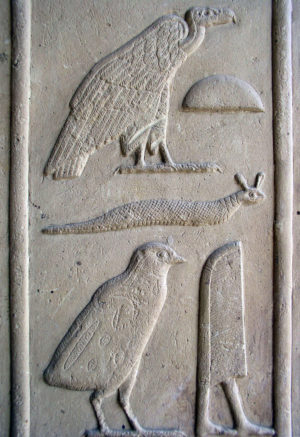

Highly detailed raised relief hieroglyphs on the White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak (Middle Kingdom). (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Text accompanied almost all images. In statuary, identifying text will appear on the back pillar or base, and relief usually has captions or longer texts that complete and elaborate on the scenes. Hieroglyphs were often rendered as tiny works of art in themselves, even though these small pictures do not always stand for what they depict; many are instead phonetic sounds. Some, however, are logographic, meaning they stand for an object or concept.

The lines blur between text and image in many cases. For instance, the name of a figure in the text on a statue will regularly omit the determinative (an unspoken sign at the end of a word that aids identification—for example, verbs of motion are followed by a pair of walking legs, names of men end with the image of a man, names of gods with the image of a seated god, etc.) at the end of the name. In these instances, the representation itself serves this function.

Collection Tour of Egyptian Art: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Egyptian art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art, ed. Melinda Hartwig (John Wiley & Sons, 2015).