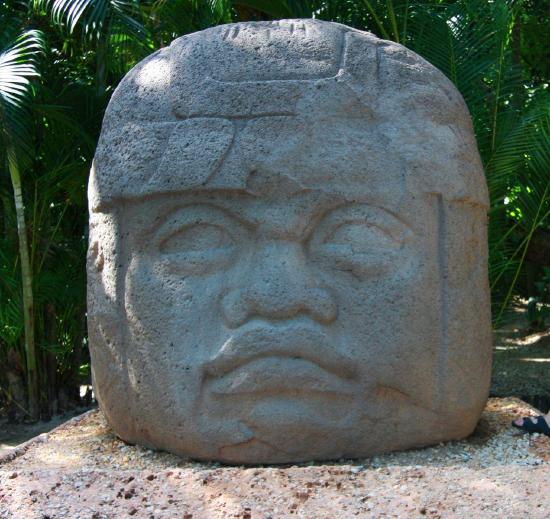

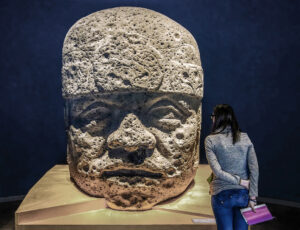

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 6, before 900 B.C.E. (Olmec), basalt, 1.67 x 1.41 x 1.26 m (Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City)

From the portraits of Benin kings and queens to the busts of Roman patricians, the history of art is a testament to our human fascination with faces. Cultures past and present have often equated the head and face with something indelible about the individual that goes beyond physical appearance, a marker of personal identity that can encompass aspects of personality, rank, or even destiny.

Many Indigenous cultures in Mesoamerica also connected notions of self or personhood to the head or face. For example, in the language of the Classic Maya (c. 250–900 C.E.) the word u’bah links the notion of self to body, and more specifically to the head or face. This term was also used when referring to the image of a person, their portrait. It is possible that the Classic Mayan language encodes an even earlier, more widespread Mesoamerican association between the self and the head, one which first appears in the art of an ancient people known today as the Olmec.

The men (and women) of stone

The Olmec of the Mexican Gulf Coast are perhaps best known today for their tradition of large-scale stone sculptures. These are among the earliest sculpted artworks in the ancient Americas found north of the Andes, dating to approximately 1600–350 B.C.E. Among the hundreds of sculptures associated with this culture, the colossal heads are undoubtedly the most famous. 16 heads, ranging from 1.47 m to 3.4 m in height and weighing between 6 and 25.3 tons, have been recovered from the three main Olmec archaeological sites: San Lorenzo, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes.

These sites each rose to dominate their respective regions consecutively during the period we refer to as Mesoamerica’s Formative Period. The earliest, San Lorenzo, dominated the Coatzalcoalcos River Basin of southern Veracruz between 1800 and 850 B.C.E., with La Venta rising to prominence in the Grijalva River Basin of northern Tabasco between c. 850 and 350 B.C.E., following San Lorenzo’s decline. Farther north, in the region of the Tuxtla Mountains, the site of Tres Zapotes only emerged as a major regional power after the dominance of La Venta began to wane, during a period we call the epi-Olmec. Although these three civic centers varied widely in terms of both chronology and topography, they are now linked by the discovery of the colossal heads. Today these massive heads are viewed as hallmark of Olmec art and society, often used as a symbol to represent the whole of Olmec culture.

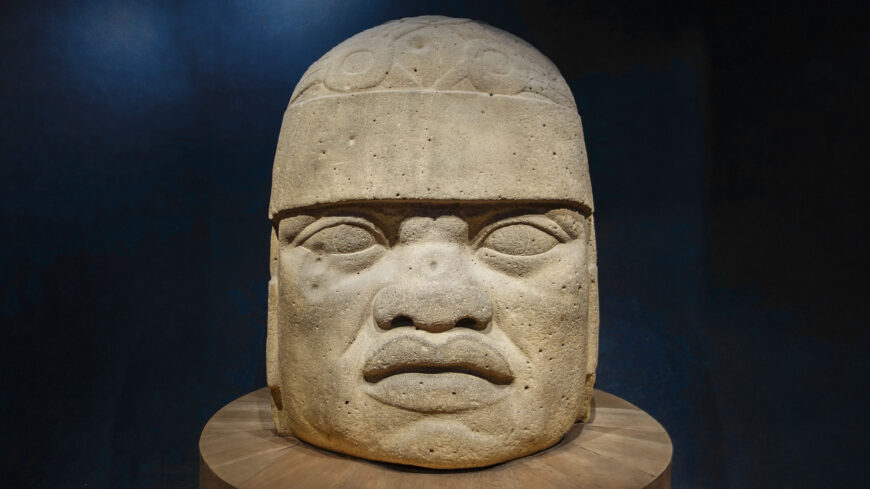

San Lorenzo Head 5, before 900 B.C.E. (Olmec), basalt, 1.86 x 1.47 x 1.15 m (Museo de Antropología de Xalapa)

“Great stone faces of the Mexican jungle”

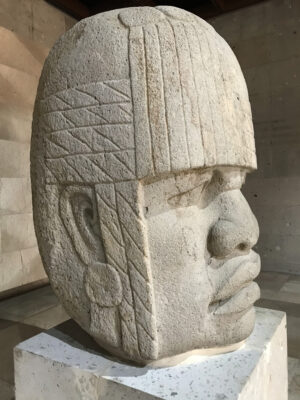

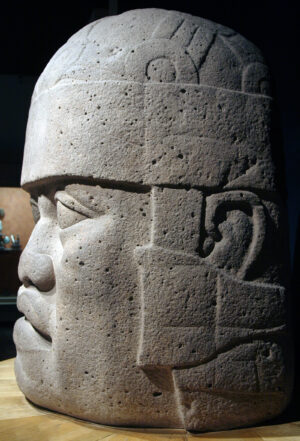

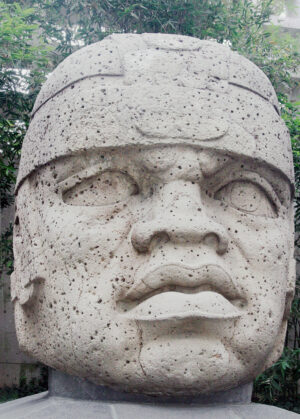

Exhibited today within the halls and courtyards of various Mexican museums, the colossal heads continue to present us with a powerful display of personhood. Many viewers have noted their sensitive naturalism, although they range from highly detailed, individualized portrayals to more generic appearances that at times eschew careful modeling for more abstracted features. Yet, even in front of the most naturalistically carved heads, the viewer is unable to forget that these are megalithic stones. The features of the individual are at times flattened or attenuated to conform to the (sometimes irregular) contours of the enormous boulder from which the head is carved. This might account for the helmet-like profile of the headdresses, which are unlike many headdresses found in other examples of Olmec art that tower vertically above the heads of their wearers (as an example, see the headdress of the figure on La Venta Stela 2). Because of their relatively shallow carving and tendency to treat each side of the stone as a surface separate from the rest of the monument, it has been noted that the Olmec technique of sculpting the heads is effectively relief sculpture in the round.

San Lorenzo Head 4, before 900 B.C.E. (Olmec), basalt, 1.78 x 1.17 x .95 m (Museo de Antropología de Xalapa)

Faces are always given the most attention by the artists, who would have sculpted the curve of each soft cheek, delicate lip, and deeply furrowed nasion, without the use of metal tools. Every face is unique; yet all are idealized according to the conventions of Olmec art, shown youthful and without blemish. A secondary area for detail is the headdress, each carved with a distinctive emblem (discussed below). The sides of the heads—including ears, ear ornaments, and the cheek flaps extending from the headdress—were generally sculpted with less care and attention to detail (perhaps areas assigned to less-skilled or experienced sculptors). The backs of the heads are the most variable, with some flat and others rounded. Some are minimally sculpted, with perhaps just the barest raised edge indicating the rim of the headdress, while others are carved with fringed feathers trailing down the back in elegant relief.

Head honchos

The Olmec colossal heads all differ in the dimensions and details of their facial features, their eye and mouth shapes, the contours of their faces and even their expressions. Combined with their unique headgear it is easy to distinguish one from the other, leading scholars to suggest that they represent specific individuals. But who were they?

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 6, before 900 B.C.E. (Olmec), basalt, 1.67 x 1.41 x 1.26 m (Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City)

Despite their age and a lack of written records, we have several clues that might help us to guess who these individuals were, or at least what their status may have been. The most visible clue is the enormous scale of the heads, along with the material from which they are carved—an igneous basalt that originated as many as 150 kilometers away from the centers where they were brought and put on display. Many people must have labored for months or even years to quarry the stone, sculpt it, and transport it via land or waterways to its final destination. In addition to the expense of such an endeavor, the scale and material also serve to communicate a sense of importance, with the visual mass or weight of the sculpture signaling the importance of the person represented. It is likely that only the highest-ranking members of society, the leaders of Olmec centers (whether rulers, military captains, religious leaders, etc.) could have commanded the necessary resources, as well as the social standing, represented by the heads. This aligns with the rest of Olmec sculpture, which includes many images of the lords and ladies of Olmec society interacting with each other and with the supernaturals or deities who were believed to govern the natural and human worlds.

Another clue to the identities of the colossal heads is found on the headdresses. It seems likely that, like later Mesoamerican peoples, the Olmec chose to insert identifying symbols on the headdresses of their highest-ranking elite. The distinctive emblems that distinguish each head are almost certainly indicators of personal identity, although we do not know if they represent individual names, titles, or family/clan affiliations.

Finally, visual analysis of the heads has noted the occasional presence of odd “scars” that appear to be the remnants of previous carving unrelated to the form of the head itself. This has led to the suggestion that at least two of the heads (and possibly many more) were re-carved from pre-existing stone monuments, specifically the large altar-thrones believed to be seats of elite authority (ex. Altar 4 from La Venta). It is possible that some of these thrones were re-sculpted into heads, possibly to signal a lord’s transition to divine ancestor after death or to convey the transfer of power between generations of elites, if the throne of a former lord was re-sculpted into a successor’s portrait. In either case, it is likely that only those of the highest rank possessed the authority and impetus to have these seats of power transformed into enormous portrait heads.

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 2, before 900 B.C.E. (Olmec), basalt, 2.69 x 1.83 x 1.05 m (Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City)

Traditionally, scholars have assumed that the heads represent only male leaders of Olmec society, based on a lack of overt feminine characteristics. However, overt masculine characteristics are also lacking. Scholars have explored the evidence for female authority among the Olmec and their presence in monumental sculpture over the past two decades. Following this work, it would be an error to assume that all the heads represent men without additional evidence. Perhaps more importantly, the lack of clearly gendered features (for the colossal heads and in Olmec sculpture more generally) may suggest that social roles and/ or authority were not primarily tied to or reliant on a person’s gender.

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 1, before 900 B.C.E. (Olmec), basalt, 2.84 x 2.11 m (Museo de Antropología de Xalapa)

Facing the past

The colossal heads are distinguished from other Olmec sculptures by their immense size, their individuality, and even certain elements of their style. However, they also exemplify a larger concern with the human head that is evident throughout the corpus of Olmec art. Heads are consistently the most detailed part of any figure, whether human or supernatural, and are proportionately enlarged or exaggerated when compared to the rest of the body. Certain categories of objects, such as greenstone masks and wooden busts, also focus exclusively on the head or face. Intriguingly, many of the full-figure sculptures of San Lorenzo have been decapitated and their heads remain undiscovered. Where they are and what was done with them remains one of the great as-of-yet unanswered questions of Olmec archaeology.

While the colossal heads underscore the significance of the human head in Olmec culture, they also present us with a picture of social power and affluence that resonates with viewers today. However, like other portraits in the history of art, it is their ability to put a human face on the ancient past that draws us in. The power of the colossal heads, like many portraits, is that they offer a form of immortality. Confronted with their stony gazes and serene expressions, we cannot help but wonder about the people they represent; who they were, how they lived, loved, and died. How perhaps, despite the millennia that separate their lives from our own, they might not have been so very different from us.

Additional resources

Olmec Art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Kathleen Berrin and Virginia M. Fields, Olmec: Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2010).

Ann Cyphers, “Las Cabezas Colosales,” Arqueología Mexicana, volume 2, number 12 (1995), pp. 43–47.

Billie Follensbee, “Unsexed Images, Gender-Neutral Costume and Gender-Ambiguous Costume in Formative Period Gulf Coast Cultures,” Wearing Culture: Dress and Regalia in Early Mesoamerica and Central America, edited by Heather Orr and Matthew G. Looper (Boulder, CO: University of Colorado Press, 2014).

Beatríz de la Fuente, Los Hombres de la Piedra: Escultura Olmeca (Mexico: Universidad Autónoma de México, 1977).

Julia Guernsey, John E. Clark, and Barbara Arroyo, The Place of Stone Monuments: Context, Use, and Meaning in Mesoamerica’s Preclassic Transition (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2010).

Christopher A. Pool, Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Matthew Stirling, “Great Stone Faces of the Mexican Jungle,” National Geographic, volume 78, number 3 (1940), pp. 309–34.