Floss silk padded robe, Western Han Dynasty, 2nd century B.C.E., length: 140 cm, overall length of the sleeves: 245 cm, width at waist: 52 cm, from tomb 1, Mawangdui, Hunan Province, China (Hunan Provincial Museum)

The discovery of three tombs at Mawangdui in Hunan Province, China in 1972 yielded thousands of artifacts, including some of the world’s oldest preserved silk paintings, clothing, and textiles. All three date to the Western Han dynasty in the 2nd century B.C.E. and belonged to a family of Han Chinese aristocrats.

Tomb 1 belonged to a female aristocrat named Xīn Zhuī 辛追, popularly known as “Lady Dai” (who died in 168 B.C.E.)

Tomb 2 belonged to the noble Lì Cāng 利蒼, Marquis of Dai, Lady Dai’s husband (who died in 186 B.C.E.)

Tomb 3 belonged to Lady Dai’s son (who also died in 168 B.C.E.) [1]

Lacquerware vessel, Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E (photo: Gary Todd)

When it was discovered, Lady Dai’s tomb was in a remarkable state of preservation with wooden objects and silks in near perfect condition, as though immune to the ravages of time. Although the construction of Lady Dai’s tomb, the largest of the three, disrupted the tombs of her husband and son, leaving them in a lesser state of preservation, all three tombs help us reconstruct this ancient family’s vision of the afterlife.

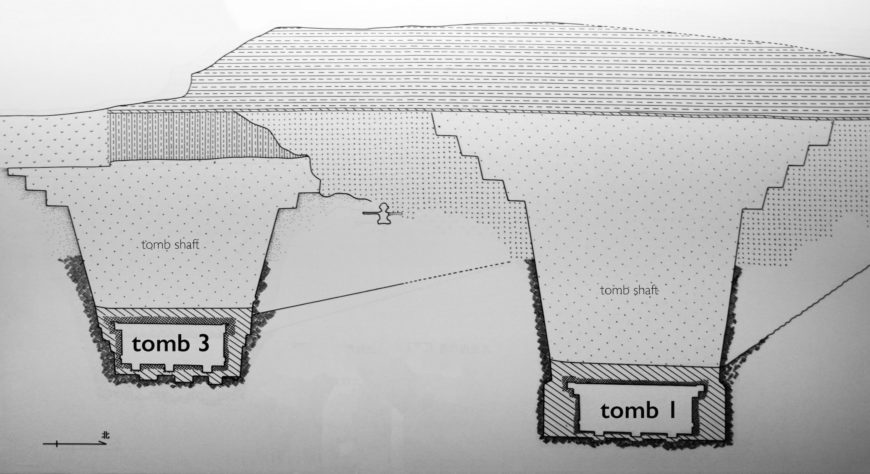

Line drawing of tombs 1 (right) and 3 (left), excavated from 1972–74 at Mawangdui, in Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E. (photo: Gary Todd)

Structure of the Mawangdui Tombs

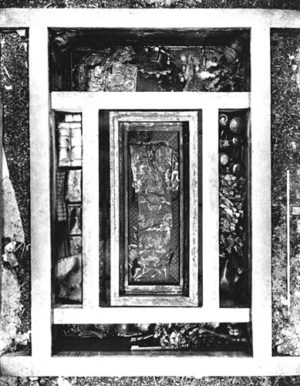

During the Western Han dynasty, elaborate tombs were constructed for the elite across the Han empire in an effort to care and appease the spirits of deceased ancestors. The three tombs at Mawangdui are rectangular vertical shaft tombs dug deep into the earth. At the bottom of each shaft, the tombs were originally equipped with a rectangular wooden burial structure (guǒ 椁) constructed of cypress planks fitted together using mortise and tenon joinery.

This type of tomb construction had an earlier precedent and was common in this region during the earlier Eastern Zhou period (771–221 B.C.E.) when it was occupied by the Chǔ 楚 kingdom. As with earlier Chu tombs, the underground wooden burial structures at Mawangdui were compartmentalized. The Mawangdui tombs contained nesting coffins at the center and extensive inventories of burial items in separate chambers surrounding the main coffin chamber. Layers of charcoal and white kaolin clay around the wooden burial structures and pounded earth in the shafts insulated the structures, and, in the case of Lady Dai’s tomb, helped preserve the entire contents, including her body.

Tomb 1

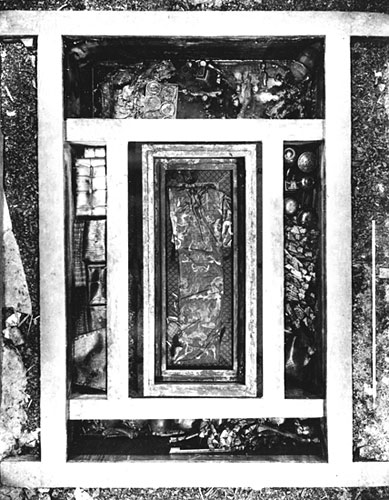

Lady Dai’s underground wooden burial structure was divided into five compartments, including a central coffin chamber surrounded by four compartments on each side for burial furnishings. At the center of the tomb, Lady Dai was buried in a series of four nesting coffins.

Nesting coffins of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E., wood, lacquered exteriors and interiors, 256 x 118 x 114 cm, 230 x 92 x 89 cm and 202 x 69 x 63cm (Hunan Provincial Museum)

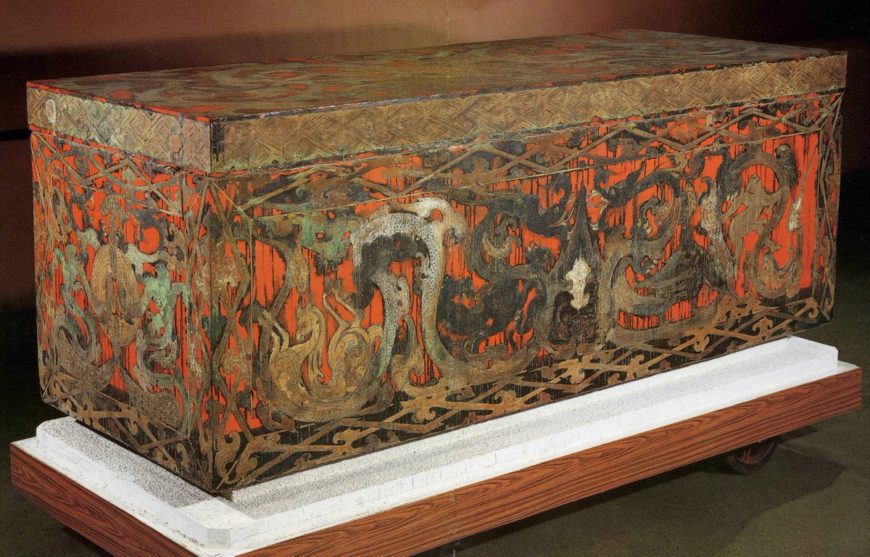

The outermost coffin was a plain box, while the three nesting coffins inside were painted with lacquer in black, red, and white. The use of lacquer, a substance derived from the lac tree native to China, is a testament to Lady Dai’s wealth and status in Han society. Lacquer was more valuable than bronze. The application of lacquer involved a tedious process of applying one layer and letting it dry before adding another, increasing the value of the material.

Black outer coffin, Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E., lacquered wood (Hunan Provincial Museum)

Stylized cloud forms and mythical creatures, detail, black outer coffin. Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E., lacquered wood (Hunan Provincial Museum)

The decoration on the three painted coffins refer to the journey of Lady Dai’s spirit to the afterlife and the world of the immortals. During the Western Han, southerners like Lady Dai believed humans had two souls, a hún 魂 that makes a dangerous journey to the afterlife, or the world of the immortals, and a pò 魄soul that remains in the tomb with the body, enjoying the many funerary offerings within.

The largest of the lacquered coffins has a black background decorated with stylized cloud forms and mythological creatures. On each side of the coffin the cloud forms are bordered by a rectangular frame of abstract patterns. At times, the clouds drift over the frame as though the celestial world populated by horned creatures, feathered immortals, and birds cannot be contained.

Red inner coffin, Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E., lacquered wood (photo: 猫猫的日记本, CC BY 4.0)

Long side panel of the coffin with two sinuous dragons, red inner coffin, Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E., lacquered wood (photo: 猫猫的日记本, CC BY 4.0)

Detail of an end side, red inner coffin, Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E., lacquered wood (Hunan Provincial Museum)

The second lacquered coffin has a red background and features auspicious animals, such as tigers and dragons, which are among the protective creatures of the cardinal directions.

On one long side panel of the coffin, two sinuous dragons confront one another at the center of the rectangular panel. On the left, a deer, contorted in a manner that shows influence from “animal style” art of the steppe, is nestled in the body of the dragon. On the right, a feathered immortal seems to dance beneath the arch of the dragon’s body. These auspicious motifs helped to guide and protect Lady Dai’s soul on its journey to immortality.

The innermost coffin is painted with black lacquer and covered with embroidered silk and satin appliqued with red and black feathers, symbolic of the immortals. The theme of immortality is consistent across the three lacquered coffins, perhaps to keep Lady Dai’s hun spirit focused on its destination as it makes the dangerous journey to immortality.

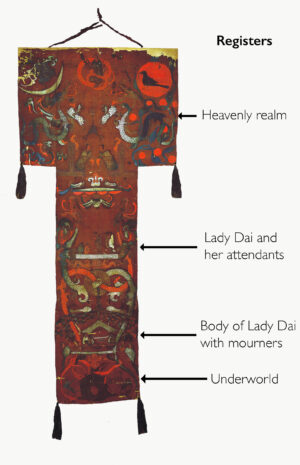

Funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E., silk, 205 x 92 x 47.7 cm (Hunan Provincial Museum)

Silks

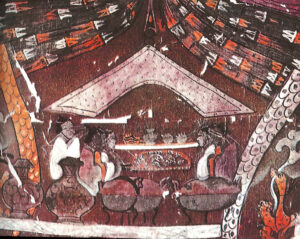

Laid face down over the top of the innermost coffin was a T-shaped banner made of silk and painted in rich mineral pigments. The painting is a narrative organized vertically from bottom to top in four sections showing Lady Dai’s journey from the terrestrial world (her funeral) to the celestial world of the immortals above.

Heavenly realm (detail), Funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui), 2nd century B.C.E., silk, 205 x 92 x 47.7 cm (Hunan Provincial Museum)

One interpretation of the iconography at the top of the banner (where the celestial world of the immortals is depicted) is that it represents the popular tale of Archer Yì 後羿 and his wife Cháng’é 嫦娥. On the right side, nine orange orbs float against the blank silk background, interspersed between a dragon and the arms of a writhing vine. The orbs might represent the nine suns the Archer Yi shot down through the branches of a mulberry tree when, one day, ten suns arose at once. On the left side of the scene, the archer’s wife Chang’e flees on the wing of a dragon toward the crescent moon with the archer’s reward for his heroic deed, the elixir of immortality.

In one version of the legend, Chang’e was punished for her theft and turned into a toad. Standing on the crescent moon on Lady Dai’s banner is a toad, which may represent Chang’e’s unfortunate punishment. A rabbit, an animal associated with the legend of Chang’e, leaps over the toad’s head. At the top of this scene is a female figure whose lower body terminates in a serpent’s tail. This may be a representation of Nǔwā 女媧, the creator goddess in Chinese mythology.

Bottom: Silk robe, Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E, silk (Hunan Provincial Museum; photo: Gary Todd)

Embroidered silk shroud, Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E, silk (Hunan Provincial Museum)

Inside the innermost coffin, Lady Dai’s body was carefully wrapped in twenty layers of luxurious embroidered and damask silk shrouds and clothing, tied together with nine silk ribbons.

Her body was perfectly intact and her skin still soft and elastic. An autopsy revealed important details about her health at the time of her death, as well as her last meal, melon. Scientists believe she died of acute gallbladder disease or from a heart attack, but they also discovered she had an unusually high accumulation of mercury and lead in her body, likely from regular ingestion. Mercury was a primary ingredient in the coveted, but ultimately deadly elixir of immortality. The discovery that Lady Dai likely ingested mercury in pursuit of immortality comes as no surprise. From the pictorial program on her lacquered coffins to her funerary banner, immortality was clearly a preoccupation of hers, one she certainly hoped to achieve in life and in death.

Examples of míngqì: clay replicas of coins (left) and painted tomb figurines made of wood (right), Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E. (Hunan Provincial Museum; photo of coins: Gary Todd; photo of figurines: Gary Todd).

Example of objects from Lady Dai’s life: lacquer tray and dishes, Tomb 1 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E. (Hunan Provincial Museum)

Lady Dai’s tomb was furnished with three categories of objects:

- míngqì 冥器 , or spirit objects, made specifically for burial (for example, the lacquered wood coffins, crude wooden figurines of servants and musicians dressed in painted or real silks, and clay coins made in imitation of real money)

- objects the tomb occupant used in her daily life (for example, household furniture, a lacquer toilet box, lacquer kitchenware (including the earliest known pair of chopsticks), musical instruments, and sumptuous silk clothing and accessories fit for the afterlife of an elite Han aristocrat

- a wide assortment of foodstuffs (meats, vegetables, fruits, cereals, etc.) for cooking and banqueting

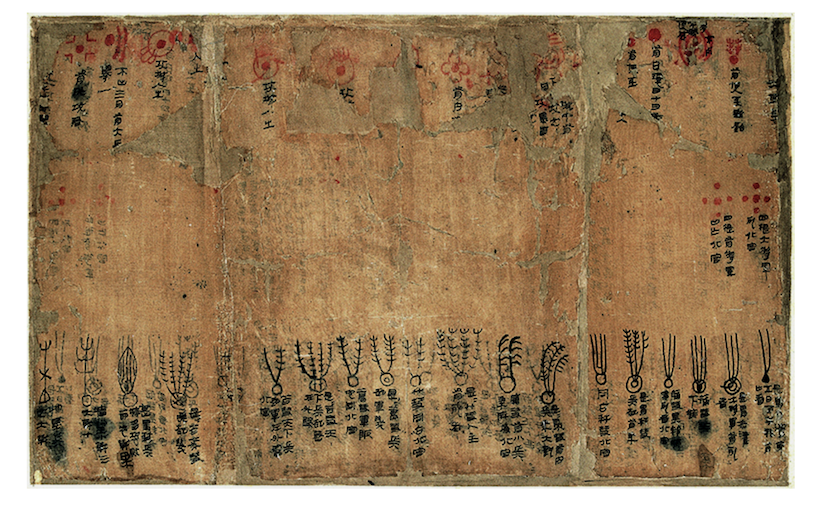

Divination by Astrological and Meteorological Phenomena, Tomb 3 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E. (Hunan Provincial Museum)

A brief note on Tomb 3

T-shaped banner, silk, Tomb 3 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E. (Hunan Provincial Museum)

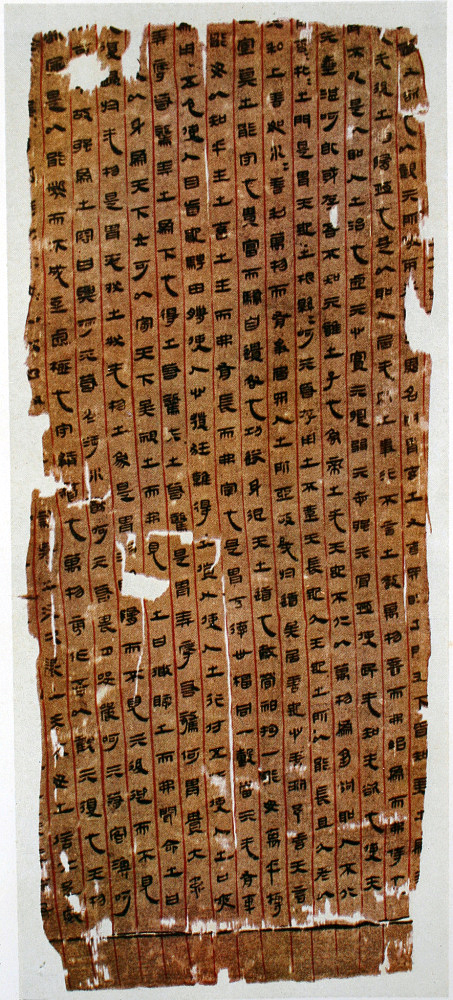

Lǎozǐ 老子,Tomb 3 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, 2nd century B.C.E. (Hunan Provincial Museum)

Although tombs 2 and 3 belonging to Lady Dai’s husband and son were in a lesser state of preservation upon discovery, Tomb 3 still yielded over 1,000 artifacts. Like Lady Dai, her son’s tomb was furnished with an assortment of mingqi, objects he owned in his lifetime, as well as provisions to keep his spirit appeased in the afterlife. Four silk paintings were preserved from his tomb, including a T-shaped banner similar in iconography to Lady Dai’s and found draped over his innermost coffin. These are among the earliest silk paintings in the history of Chinese art. Perhaps the most important discovery in his tomb, however, was an archive of texts written on bamboo, wood, and silk. These included well known works like the Lǎozǐ 老子, attributed to the 6th century B.C.E. Daoist philosopher Laozi; the Yǐjīng 已經 (Book of Changes), an ancient divination text; as well as important medical, astronomical, and cosmological texts, just to name a few. The Laozi manuscripts found in Tomb 3 are still, to this day, the earliest extant copies known.

Important insights

Discoveries from Tombs 1 and 3 at Mawangdui give us important insight into the lives and afterlife beliefs of an elite family living in south China during the Western Han dynasty. For the “Dai” family, furnishing the tombs with the comforts of home ensured a peaceful afterlife for the po soul, while a consistent visual program focusing on the journey to the celestial world equipped the hun soul for the search for immortality.

Notes:

[1] The occupants of the tombs and the dates of their deaths were identified by inscriptions on artifacts in the tombs. The tombs were labeled 1, 2, and 3 based on the order in which they were discovered.

Additional resources:

Pirazzoli-tʼSerstevens, Michèle, The Han Dynasty, translated by Janet Seligman (New York: Rizzoli, 1982).

Cite this page as: Dr. Cortney E. Chaffin, “The search for immortality: The Tomb of Lady Dai,” in Smarthistory, January 10, 2022, accessed April 30, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/tomb-of-lady-dai/.