A conversation with Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Steven Zucker at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Temple of Zeus at Olympia, digital reconstruction (animation still © Microsoft, with the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports and Iconem)

Around 471 B.C.E., after many years of conflict, a long standing dispute between the towns of Elis and Pisa in the Peloponnese region of Greece finally ended with a decisive victory for Elis. With this triumph, Elis gained control of the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia, which was at that time one of the most important places of worship in the Greek world. In antiquity, people traveled hundreds of miles to visit the sanctuary at Olympia, where they could worship Zeus, the king of the Olympian gods, and witness the Olympic games that took place there every four years.

Map of the Peloponnese region of ancient Greece with Elis, Pisa, and Olympia (underlying map © Google)

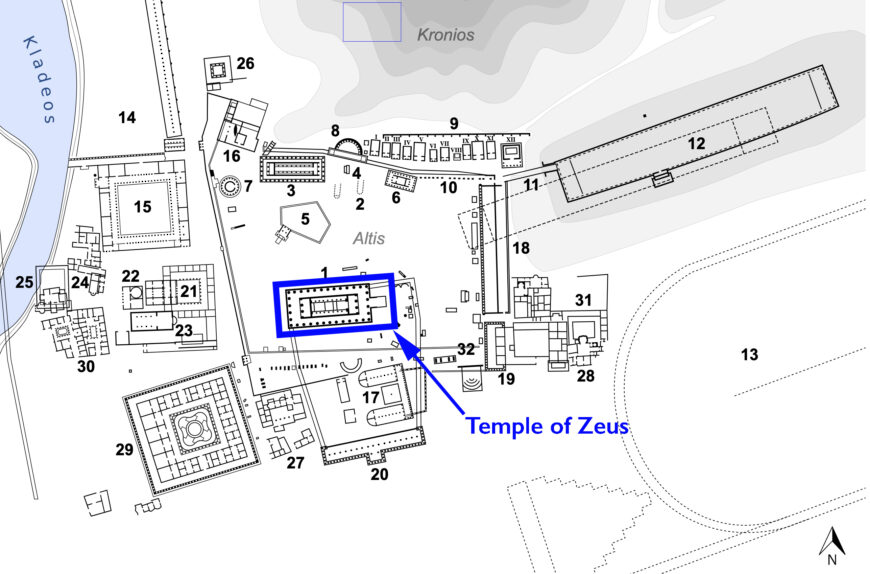

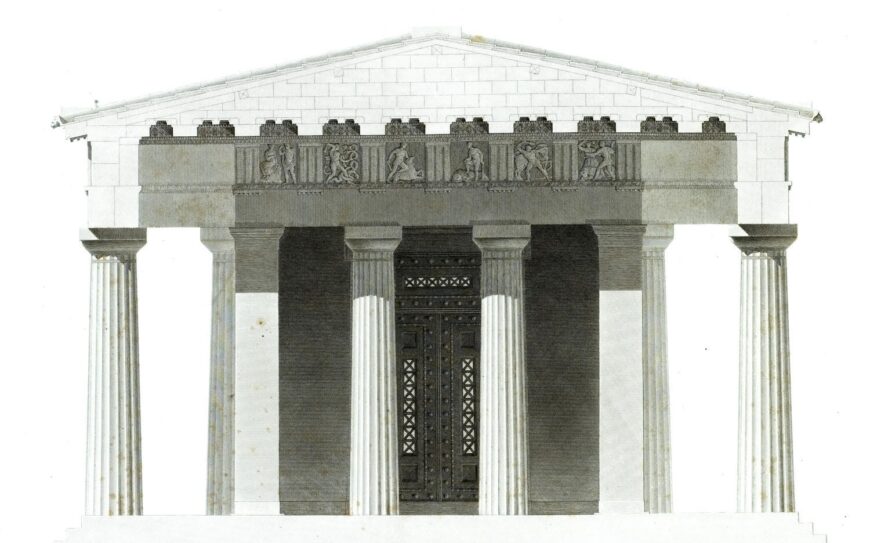

The people of Elis decided to build a new Temple of Zeus to celebrate their victory. They hired a local architect, Libon of Elis, to plan and build the structure. Construction began in 470 B.C.E. was completed by 457 B.C.E. [1]

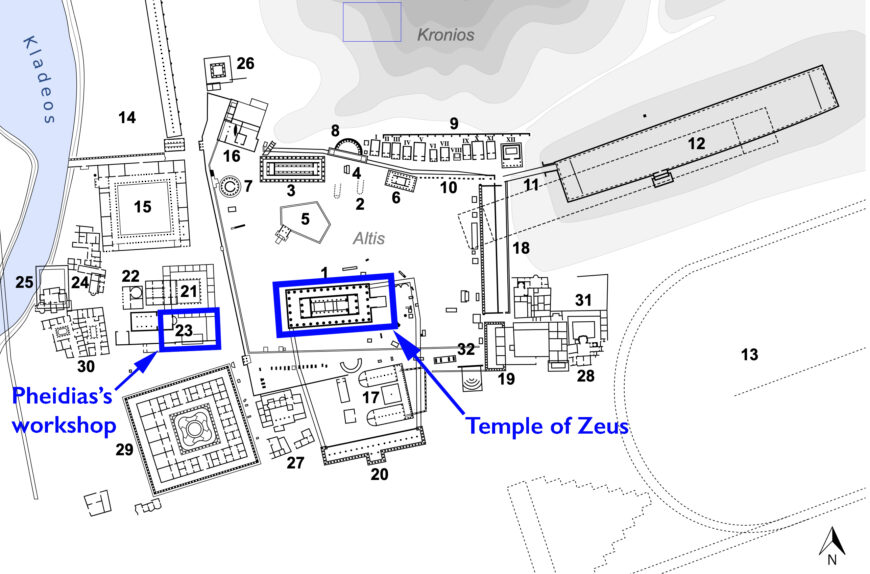

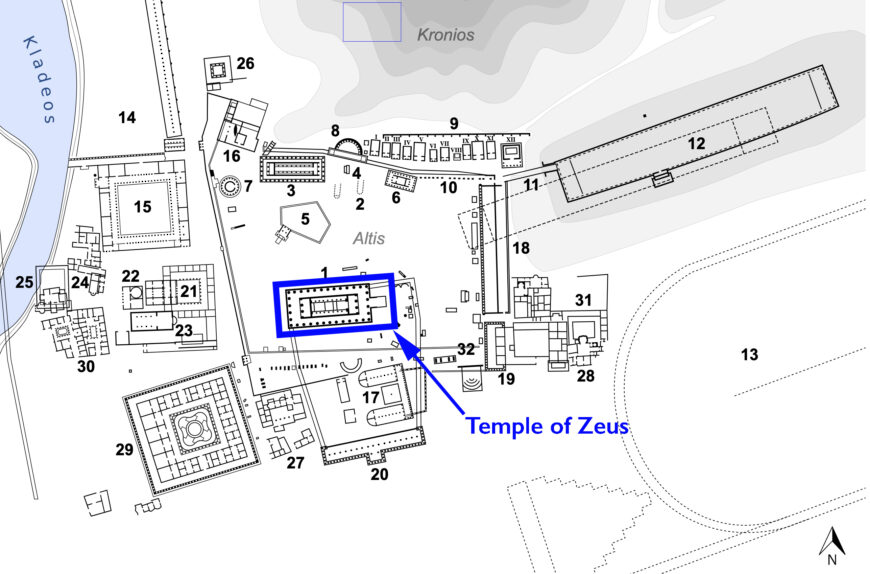

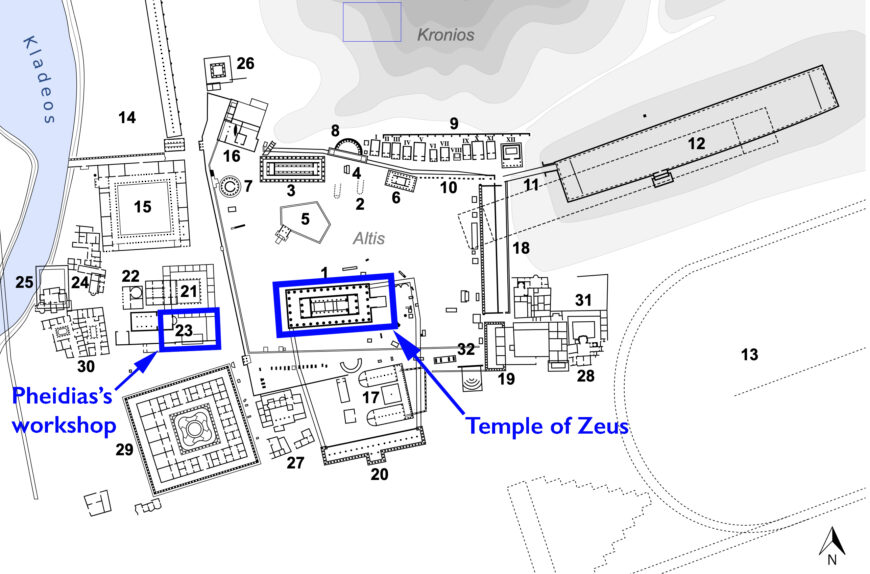

Site plan of the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia, with the Temple of Zeus highlighted

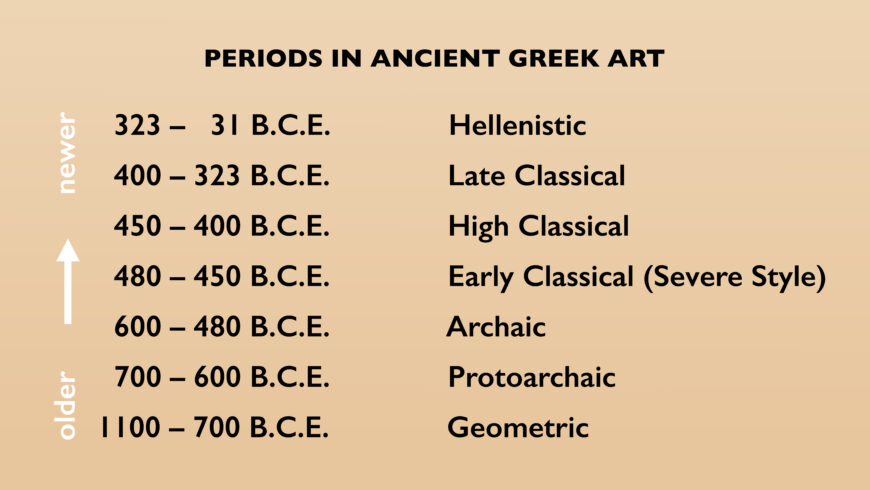

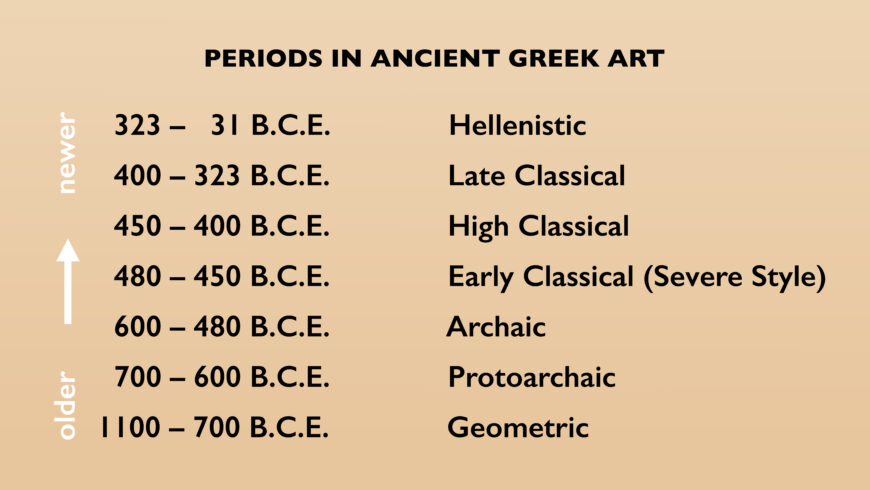

At that time, the area that we know today as Greece was divided into city-states. The new Temple of Zeus was situated within the holy land of the Panhellenic sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia, so it was accessible to people living in all city-states. The temple was seen by visitors from across the Greek world for centuries until an earthquake caused its collapse in the 5th century C.E. [2] Its exterior was decorated with sculptures that told stories from popular myths, many of which the ancient Greeks understood to be stories from their collective history. These narratives, which offered morals about the strength of the Greeks and the power of the gods, carried particular meaning for visitors to Olympia. The sculptures’ clear and distinctive Early Classical style helped them convey these messages to a wide audience.

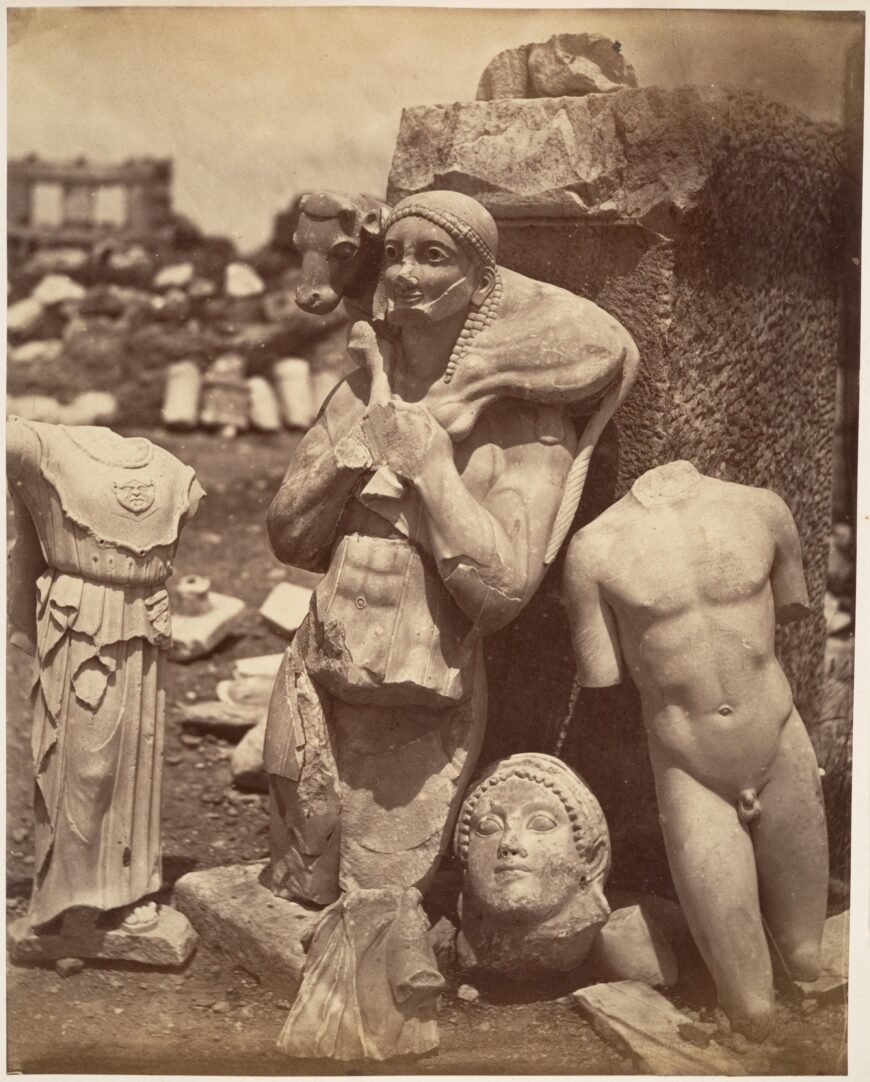

Today, our understanding of the Temple of Zeus is greatly helped by several sources. First, many of the structure’s Early Classical architectural decorations are still preserved. After the temple collapsed, these sculptures were reused in other buildings and later covered by silt from a nearby river. German archaeologists recovered these sculptures during their excavations at Olympia in the late 1800s. Continuing archaeological study of the temple and its decorations help us understand its original appearance.

Another crucial source is the Roman travel writer Pausanias, who visited Olympia in the 2nd century C.E., when the Temple of Zeus was still standing. His detailed account of the temple, its decorations, and its cult statue, as well as the sanctuary as a whole, provides much useful information. [3]

Ruins of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, with the sole reconstructed column visible in the background (Archaeological Site of Olympia; photo: Andy Hay, CC BY 2.0)

Plan and construction

Many ancient Greek buildings followed one of three conventional architectural orders. The Temple of Zeus at Olympia adheres to the Doric order. Like other temples in the Doric order, the temple’s columns have plain capitals and sit directly on the stylobate. However, the Early Classical columns of the temple are both taller and thinner than the columns of earlier Archaic Doric temples. This alteration made the structure look lighter and taller overall, which fit with the newly evolving stylistic preferences of the Classical period. [4]

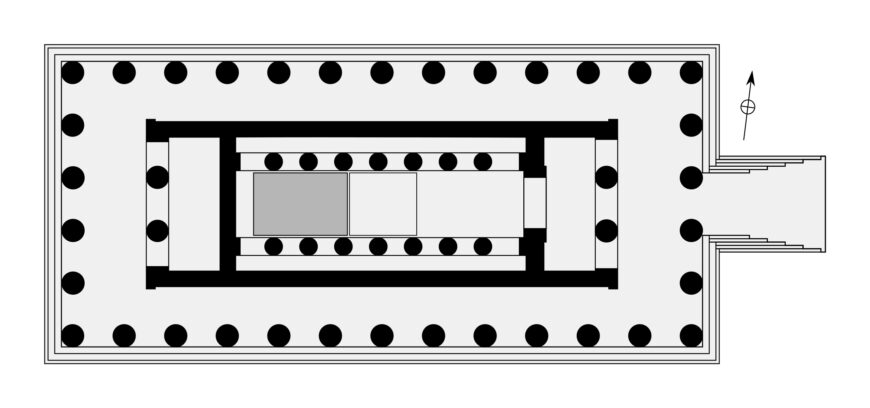

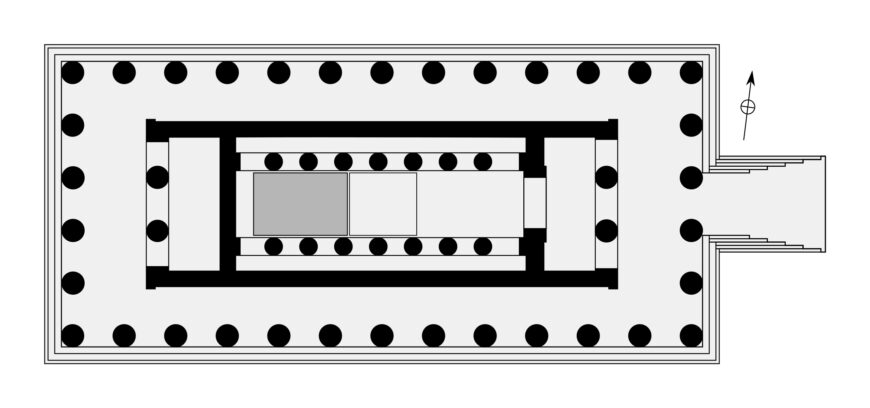

Plan of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., limestone and marble, 27.7 x 64.1 m

The Temple of Zeus also follows the rule of Classical architecture that the number of columns on its long sides must be one more than double the number of columns on its short sides. [5] As a result, there are 6 columns on each of the temple’s east and west façades, and 13 columns on each of its longer north and south sides.

Most of the Temple of Zeus was built of local limestone. The quality of this limestone was not ideal, and the stone often had pockmarks. To cover up these imperfections, the builders of the temple covered the limestone with stucco, which made it look like marble, a more expensive and highly valued material. Although most of the temple’s structural blocks were made of limestone, its roof tiles and much of its architectural decoration—including the sculptures that filled its pediments and its relief metopes—were made of marble that was imported from the island of Paros in the Cyclades. [6]

When it was completed in 457 B.C.E., the Temple of Zeus was the largest temple on mainland Greece (though there were larger temples elsewhere in the Greek world). [7]

Pediments

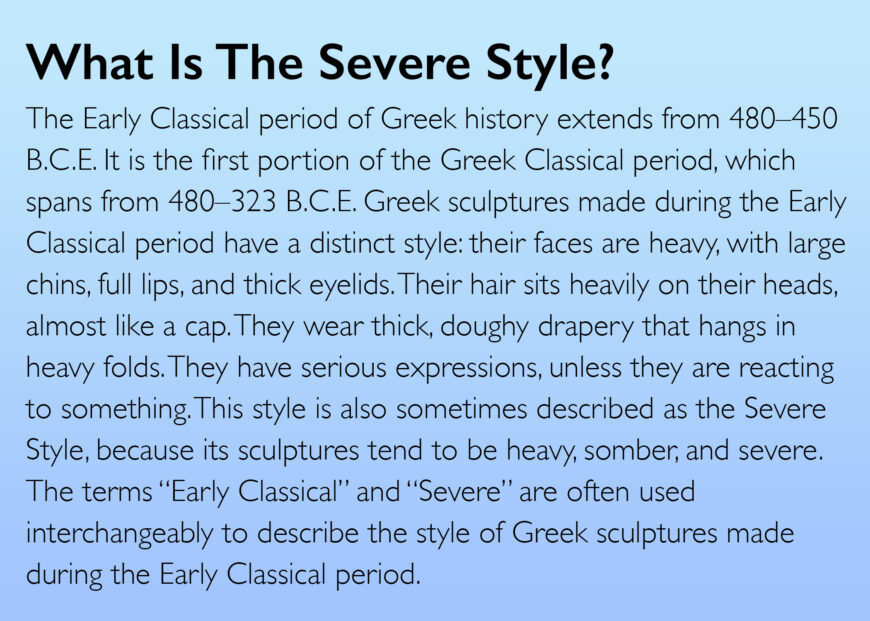

Both of the pediments of the Temple of Zeus were lavishly decorated with larger-than-life sculpted narratives. While they depict different myths, both pediments tell stories that were familiar and relevant to ancient viewers. The pediments also share the same representational style, which is typical of the Early Classical period and often called the Severe Style because of its simplicity, seriousness, and heaviness.

West pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble, 26 m wide (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0)

West pediment

The west pediment of the temple shows a story that was well known to all Greek visitors at Olympia. In the mythical past, the king of a group of legendary Greek people known as the Lapiths had a large wedding celebration. In addition to inviting many of his fellow Lapiths to the party, King Perithoos invited his friend Theseus, a famous Athenian hero, and the centaurs, half-man half-horse hybrids who lived in the same region as the Lapiths. The centaurs, who were unaccustomed to drinking wine (the Greeks’ preferred beverage at such parties), quickly became intoxicated. Drunk centaurs attacked Lapith women, sexually assaulting them during the wedding feast. Eventually, with the help of the Lapith men, Perithoos and Theseus subdued the centaurs and saved the women. This battle, known as the Centauromachy, was popular in ancient Greek art, but the sculptors at Olympia were the first to show it on such a grand scale in architectural sculpture. [8]

The battle, as depicted in the west pediment, is a dynamic event full of motion and struggle. Figures are paired in groups of two and three, creating pointed interactions that contribute to the overall sense of chaotic violence. Their movements are believable and their bodies are realistic, seemingly full of muscle even though they are stone.

Lapith woman and a centaur (detail), west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble. The drill holes in the centaur’s head would once have held metal attachments, perhaps for locks of hair (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0)

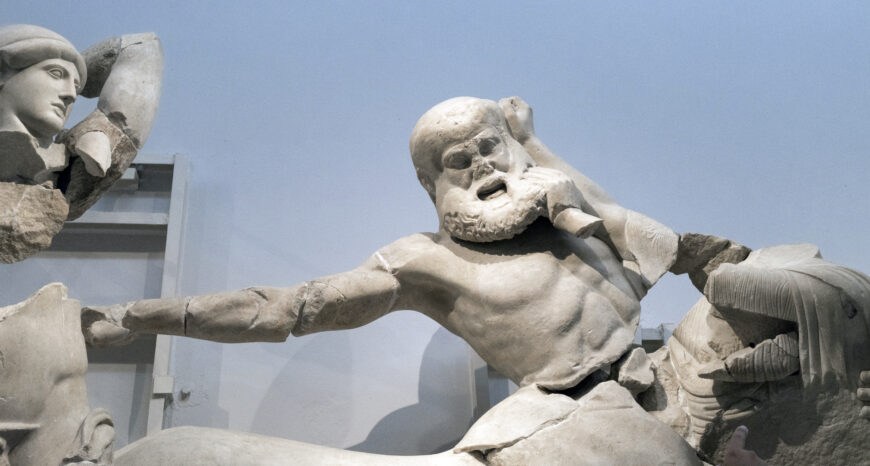

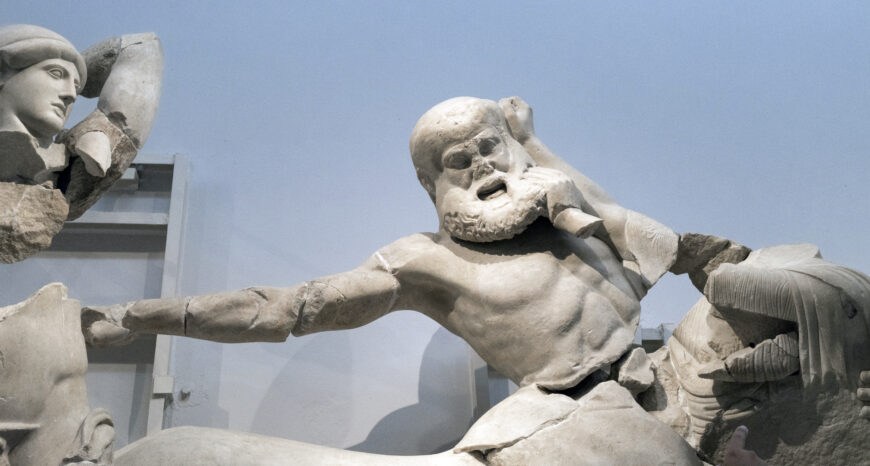

Close to the center of the pediment, one Lapith woman fights back against her attacker. As the centaur tries to pick her up and carry her away, she tries to pry his hands off her chest and elbows him in the head, connecting her left elbow with the right side of his face. Although his face is mostly worn away, the centaur appears to react with a grimace. The expression of pain on the centaur’s face reflects the sculptors’ interest in portraying responsive emotion, an important characteristic of the Early Classical style. The Lapith woman, on the other hand, appears unmoved. As a respectable Greek woman, she maintains composure even under attack. Many of her features are typical of the Early Classical, or Severe, style. Her dress falls heavily against her body, with a believable weight and thick folds that make it look like dough. Her face is also rounded and heavy, with a large chin, full lips, and thick eyelids.

Theseus, a centaur, and a Lapith woman (detail), west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Elsewhere in the pediment, the battle rages on. One centaur screams, in fear or in pain, as a Lapith woman grasps his hair and beard in an attempt to push him away. The fingers of her left hand sink believably into the centaur’s beard. His open mouth and furrowed brow dramatize his emotions. His muscles strain beneath the skin of his human torso as he stretches away from the woman attacking him and reaches an arm out towards another attacker who approaches him from behind. The man to the left of the stricken centaur is probably the Athenian hero Theseus. [9] His face is calm and his arm is raised as he prepares to strike the centaur. This moment is telling: although the battle is shown as an active, undecided conflict, ancient viewers would know that the Greeks would emerge victorious.

Apollo (detail), west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble, 3.3 m high (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC-BY-NC 2.0)

At the center of the pediment, the god Apollo stands still. His unmoving presence contrasts sharply with the struggle swirling around him. While Apollo’s body faces frontally, he turns his head to his right as he holds his arm out and gestures in the same direction. He may be silently directing the action of the battle and deciding its outcome, or perhaps he is pointing towards a fighter he particularly favors or dislikes. [10] While Apollo’s gesture is difficult to decipher, it is relatively easy to see that the centaurs and Lapiths around him seem completely unaware of his presence. Surely, if they saw a god in their midst, they would react with wonder and surprise. Instead, we are likely meant to understand Apollo as a kind of apparition: his presence at the battle is undeniable, but those fighting do not see him. [11] Instead, the visitors to the sanctuary of Olympia were given the exclusive opportunity to see this perfected image of the god, standing some 3.3 meters (10.82 feet) tall, at the center of the temple’s west pediment.

Apollo’s face (detail), west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC-BY-NC 2.0)

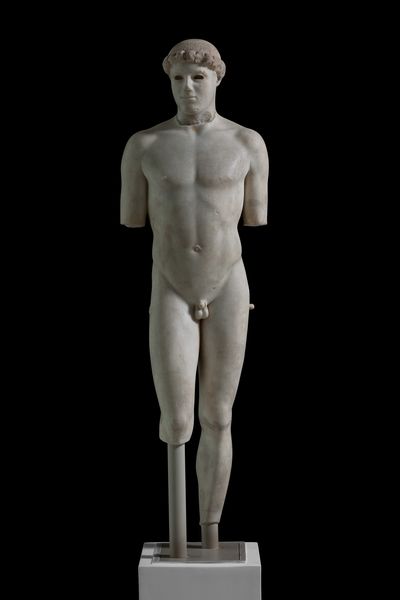

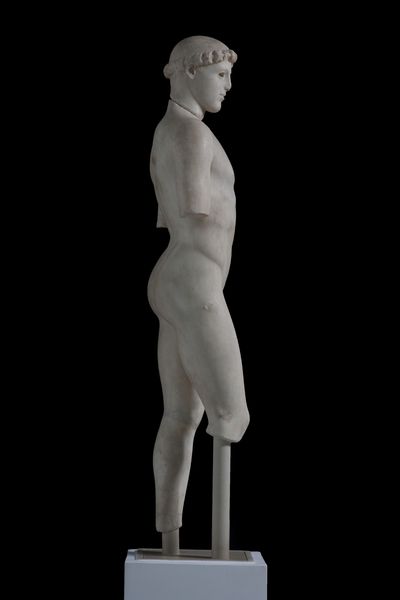

Like the other Early Classical figures around him, Apollo has a heavy chin, thick eyelids, and pillowy lips. His hair sits heavily on his head, almost like a cap, and somewhat resembles the hair of the Early Classical Kritios Boy. His mantle rests heavily on his shoulder in thick, doughy folds. Although Apollo is in the same representational style as the Lapiths and centaurs around him, his central position, large size, and calm presence set him apart as divine. Devout visitors to the sanctuary of Olympia would be awed to see an Olympian god on display like this.

Why did the architect and sculptors who made the Temple of Zeus depict a centauromachy on its west pediment? Overall, the story demonstrates the strength and heroism of the Greeks. It conveys an important, violent message about Greek superiority to everyone who sees it. The wild centaurs upended the norms of ancient Greek society when they disrupted a wedding and assaulted their fellow guests. The Greek Lapiths’ swift retaliation was understood as heroic because it restored order and civility.

As Judith Barringer points out, the centauromachy on the west pediment is depicted in a way that makes it particularly relevant to Olympia, where young athletes from many regions of Greece battled for prizes in the ancient Olympic games. [12] Many of the Greek heroes in the pediment fight centaurs with their bare hands, dominating with the sheer force of their physical strength, the same strength that athletes relied on to win competitions.

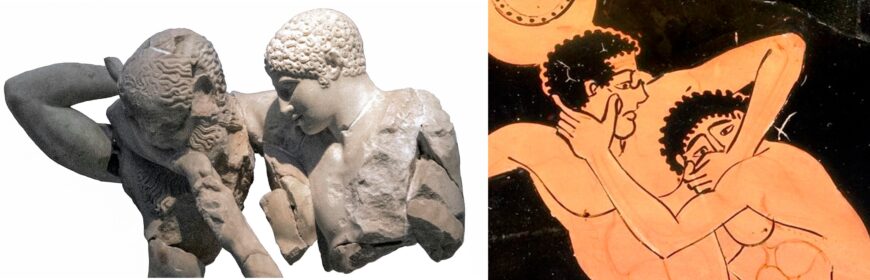

Left: Centaur and a Lapith man (detail), west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Men wrestling on the exterior of an Attic red-figure cup (detail), attributed to the Foundry Painter, Archaic, c. 490–480 B.C.E., ceramic (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

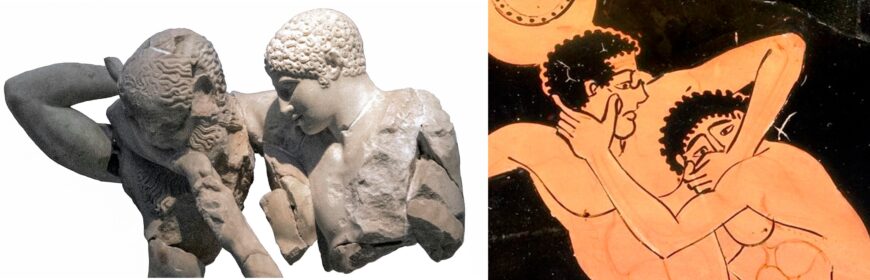

The similarities between the mythical battle and athletic competitions are made even more explicit in the sculptures’ details. The classicist Wendy Raschke has noted that several of the Lapiths grasp the centaurs in postures that seem to intentionally recall wrestling holds that real Greek athletes used. [13] For example, one Lapith whose arm is being bitten by a centaur is holding his opponent in a type of neck-hold that was commonly used in the pankration, an unarmed combat sport that used brutal wrestling and boxing techniques. In antiquity, athletes competed in the pankration at the Olympic games. An athlete depicted on this cup holds his opponent in a nearly identical pose. One scholar has even pointed out that this same Lapith, who grapples with a centaur even as his arm is bitten, has cauliflower ear, a real deformity that often afflicts boxers and occurs when an ear is repeatedly hit. [14]

The sculptors who carved the west pediment figures included these details to make this centauromachy especially relevant to, and effective for, their audience at Olympia. Young athletes arriving to compete in the Olympic games would see themselves in this dramatic tale of heroism, and understand their physical prowess to suggest a certain strength of character, which they might someday use to defend their society.

East pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble, 26 m wide (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0)

East pediment

When visitors to the Temple of Zeus at Olympia encountered the building’s east pediment, on the front of the building, they saw a very different scene from the frenzied battle they witnessed in the west pediment. Here, all is calm. No one moves dramatically, or even seems to interact with each other. Instead, the moment depicted is one of anticipation. The chariots that once flanked the five central figures (now lost, though fragments of the horses that pulled them survive) would soon speed away and participate in a race that would shape the future of Olympia and the entire Peloponnese.

Central figures of the east pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Zeus (detail), east pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Troy McKaskle, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The most important characters in this story are depicted in the middle of the pediment. At the very center, Zeus stands with a cloak wrapped around his waist. The thick folds of the drapery are typical of the Early Classical style, as is the god’s perfectly muscular chest. Although Zeus’s legs are only partially preserved, we can see that he bears most of his weight on his right leg, while his left leg bends. This shifting posture imbues the statue with life, and reveals an interest in realism that is typical of the Early Classical period. [15] Like Apollo in the west pediment, Zeus seems to be invisible to most of the people around him, even though his commanding presence is unavoidable to us, the mortal viewers. His appearance in the scene is likely meant to suggest that he will be watching over—and perhaps arbitrating—the chariot race that is about to start. Regardless of his exact role in the scene, there is no doubt that a larger-than-life representation of Zeus was an appropriate decoration for the center of his temple’s east pediment. From this lofty perch on his temple, he could look down at the visitors in his most important sanctuary.

The men who will soon compete in the chariot race stand on either side of Zeus. Their story is of crucial importance to the history of the Peloponnese. [16] On Zeus’s right is King Oinomaos, a fabled king of Pisa (the long-standing rival of Elis, the city that built this very temple after their victory against Pisa in the Early Classical period). His wife Sterope stands beside him, wearing a heavy, doughy garment and crossing her arms. Legend has it that when Oinomaos’s daughter, Hippodameia, became eligible for marriage, Oinomaos insisted on competing with all of her suitors in a chariot race. Whoever won a victory against Oinomaos would also win Hippodameia’s hand in marriage and control of Pisa. Thirteen suitors, one after another, raced Oinomaos. Oinomaos defeated each of them, and subsequently killed them.

Finally, a fourteenth suitor challenged Oinomaos to a chariot race. This young man, whose name is Pelops, stands on Zeus’s left. He is beardless, indicating that he is younger than Oinomaos. Ancient visitors to Olympia who were familiar with this story would know that Pelops won the race against Oinomaos, and with it the kingdom of Pisa and a new bride. [17] Pelops’s soon-to-be wife, Hippodameia, stands beside him. With her left hand she pulls at the left shoulder of her garment, a gesture of modesty that was often associated with brides in ancient Greek imagery. [18]

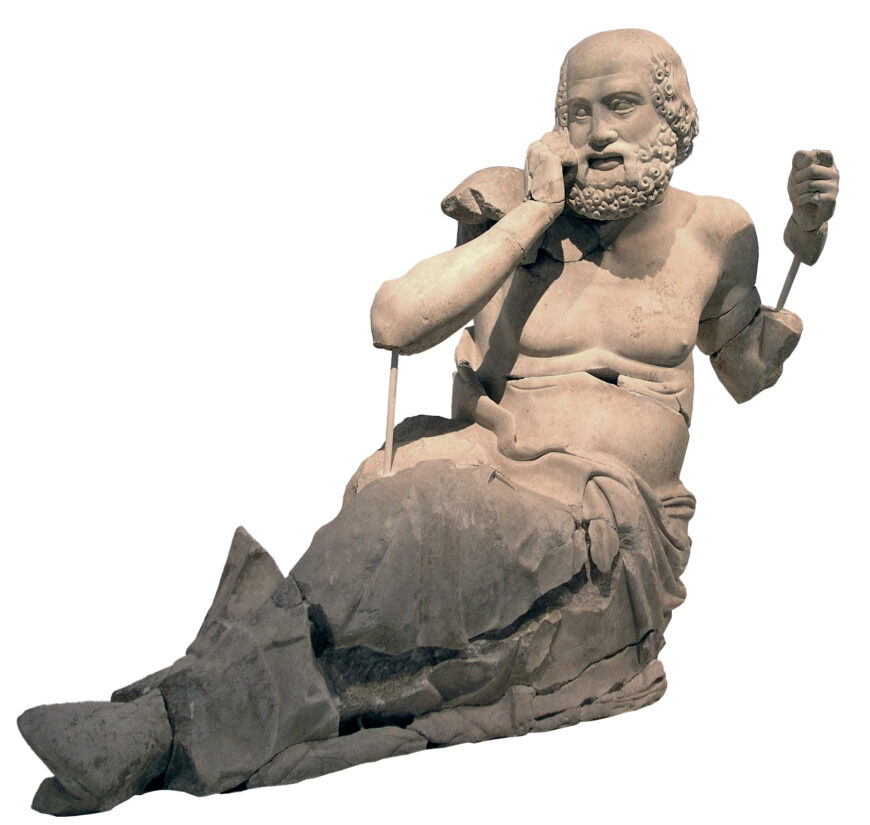

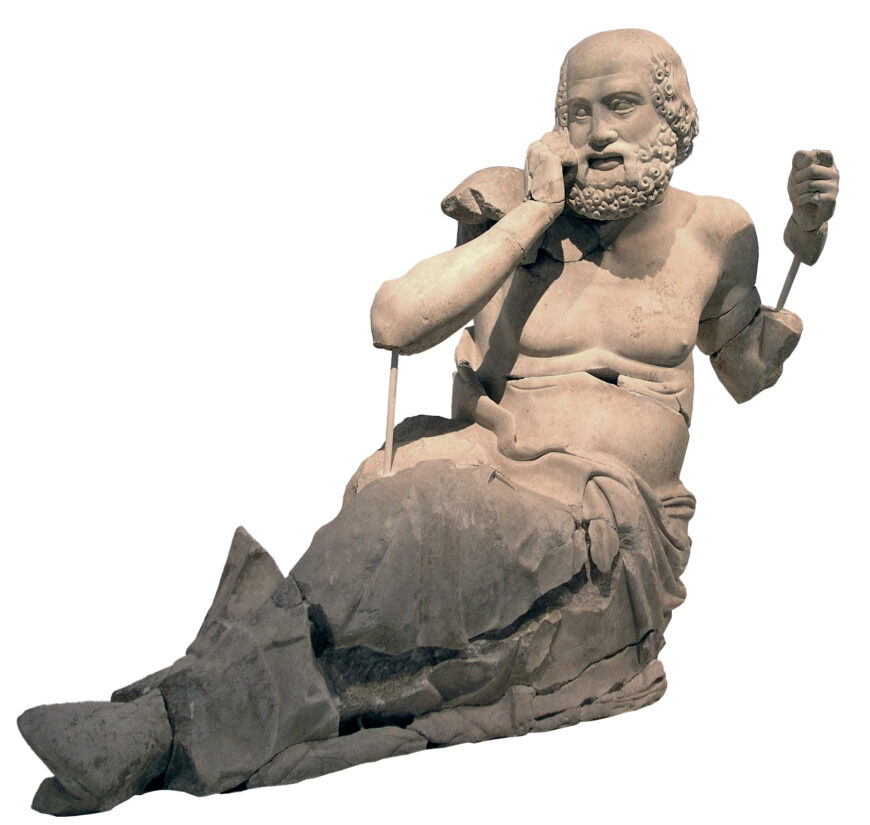

Seer (detail), east pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Angela Monika Arnold, CC BY 3.0)

Despite the impending competition, the people in the pediment are passive, apparently unaware of the unexpected turn of events that will soon occur. The only figure who expresses clear concern about the race is an old man who sits behind the chariot next to Pelops. His age is indicated by his slightly sagging chest and his bald scalp, both realistic details that are typical of the Early Classical style. His expression suggests anxiety: his brow is wrinkled, his eyes look warily towards the competitors at the center of the pediment, and he raises his fist to his cheek in a gesture of concern. The man’s age and awareness of events that have not yet happened suggest that he is a seer, a person with the ability to see the future.

The story in the east pediment is relevant to its Olympic context in many ways. It relates an important moment in local lore, when Pelops won control of Pisa. In fact, in one poem he wrote in 476 B.C.E., the Greek poet Pindar said that Pelops himself founded the Olympic Games after he won his race against Oinomaos. [19]

For ancient viewers to understand this narrative, they would have to be familiar with the myth of Pelops and Oinomaos. It is likely that many were, and that still others were told the story by companions or guides as they stood before the temple. But even those viewers who could not identify Pelops or Oinomaos would find something of interest in this composition. In the actual ancient Olympics, chariot races were the most popular event for many centuries. They were prestigious and dangerous. High above the sanctuary of Olympia, facing towards the stadium where real chariot races occurred, these sculptures immortalized the quiet anticipation that precedes a competition. Just as Zeus appears in the middle of the pediment, worshippers and athletes competing in games to honor the god might imagine Zeus’s presence in their midst as they passed through his sanctuary.

Metopes

In addition to having elaborately decorated pediments, the Temple of Zeus at Olympia was adorned with 12 sculpted metopes. The relief metopes did not wrap all the way around the temple. Instead, they were only on the shorter east and west sides of the temple. Six appeared on the front (east), while another six were on the back (west).

Restored cross section of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia showing the position of the metopes above the porch, by Guillaume-Abel Blouet and Achille Poirot, c. 1831

The metopes were also placed in a somewhat unusual location on the temple. They did not appear on the exterior façades, directly beneath the pediments (which was more typical). Instead, they decorated the exterior walls of the cella, so that the viewer would have to step up in between the columns to see them. [20]

Although the metopes are smaller than the pediments, each measuring about 1.6 meters (5 feet 3 inches) square, they are impressive in their own right. They show the 12 labors of Herakles, a series of extremely difficult tasks that the hero completed over a number of years. Each metope tells the story of a single labor and constitutes an independent narrative. But together, the metopes tell a larger story about the greatest Greek hero triumphing against every imaginable opponent and earning his fame.

Herakles is shown without a beard (and thus as a young man) in the first metope from the temple, but by the last metope he has grown a thick beard, indicating that he has aged into adulthood. Left: Herakles’s face (detail), west metope 1 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Herakles cleaning the Augean Stables (detail), east metope 6 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Jean Housen, CC BY-SA 4.0)

There is no doubt that the sculptors intended these metopes to show several related stories: from the first metope to the last, Herakles noticeably ages. [21] In his first labor, depicted on the first metope, he is a young, beardless man who sits wearily after defeating his foe; on the last metope he is bearded and mature, strenuously finishing a final task. These depictions of great physical strength performed by a popular hero were suitable for the sanctuary at Olympia, where athletic competitions were so significant. [22] Most of the labors shown in these metopes took place in the Peloponnese, the region in which Olympia is situated, which probably made them feel even more relevant to the temple’s visitors. Moreover, these mythic stories were especially fitting decorations for the Temple of Zeus because Zeus was Herakles’s father, and because some myth traditions suggested that Herakles, not Pelops, founded the Olympic games. [23]

The metopes display several typical features of Early Classical art. The figures who populate them have the cap-like hair, thick eyelids, and doughy drapery we have come to expect of the Early Classical style. Some of the scenes are full of dramatic motion, while other, calmer scenes reveal an interest in the emotions of their characters. By looking closely at several of the better preserved metopes from the temple, we will see how the sculptors depicted Herakles’s labors.

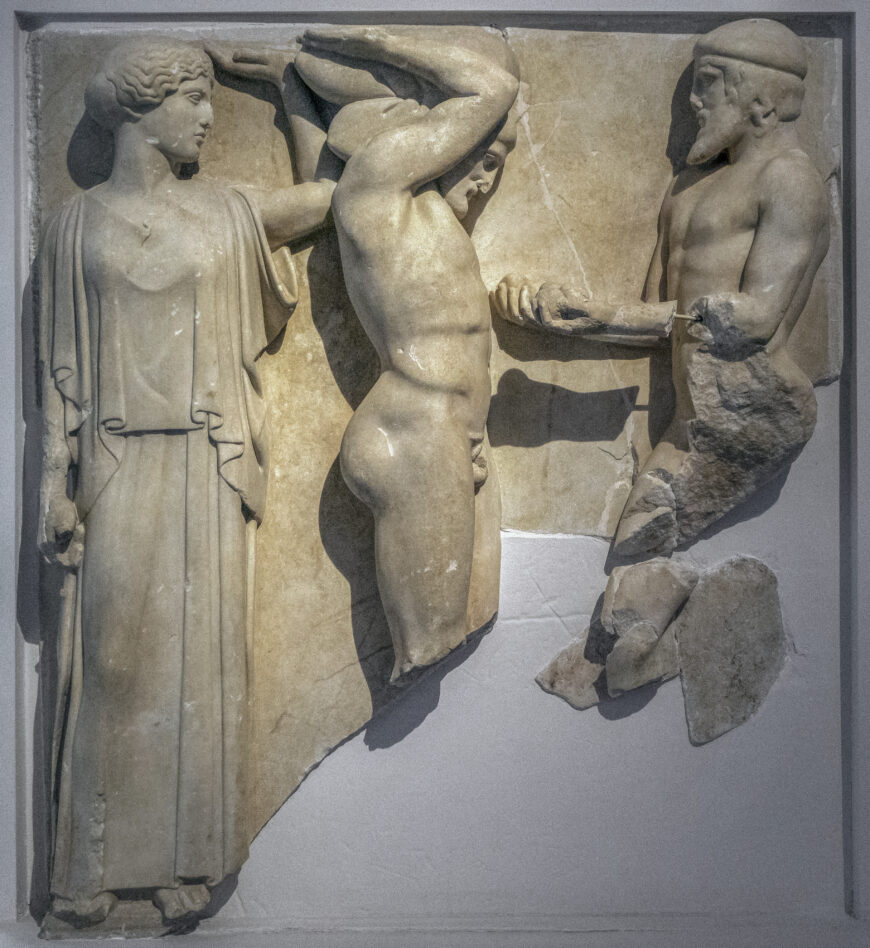

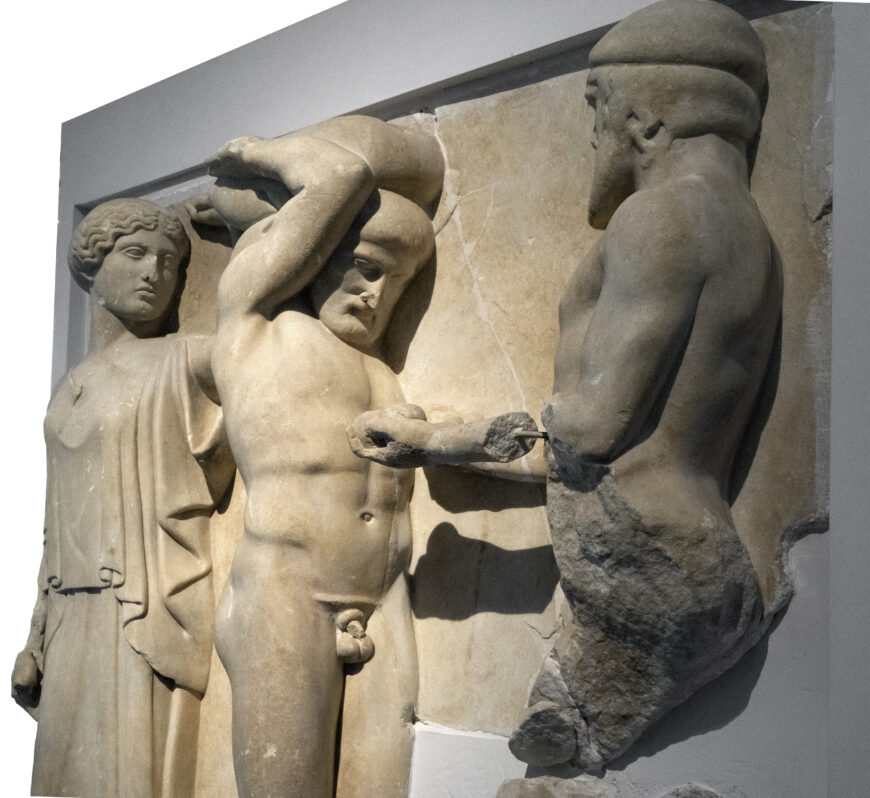

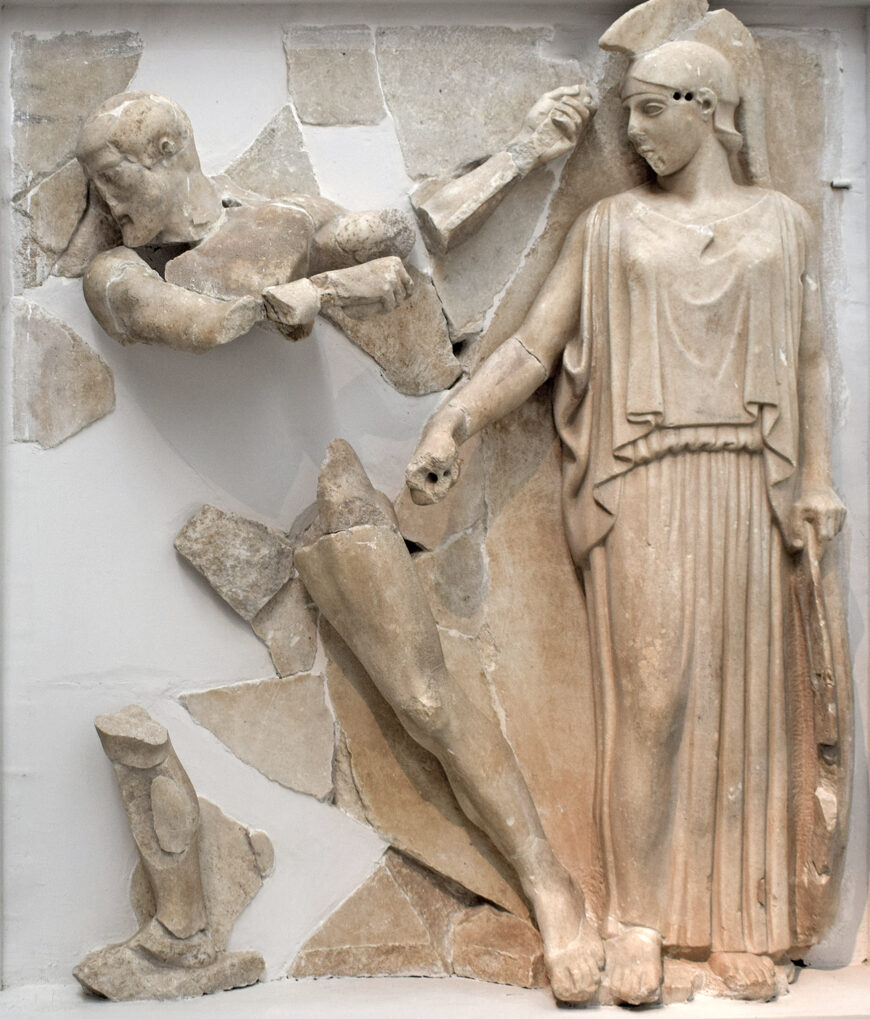

West metope 3 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble, 1.6 x 1.6 m (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the third metope on the west side of the temple, Herakles is shown in the quiet moments after he has completed a labor. He has just defeated the Stymphalian Birds (a group of man-eating birds that were attacking people living near them). Herakles was at first unable to access the swamp where the birds lived, but the goddess Athena provided him with much needed assistance. She appears next to him on the metope. She sits on a rock and turns back to look towards the hero, who reaches his arm out to pass her something, perhaps one of the birds. Her dress falls heavily against her body, revealing the shape of her chest and legs even as it conceals them. The thick folds of the drapery, as well as her cap-like hair and placid expression, are characteristics of the Early Classical style. The nude Herakles is shown with an idealized body that moves believably in space. Although this is a relief sculpture, both Athena and Herakles twist and turn in order to interact realistically. To achieve this naturalistic motion, the sculptor has carved his relief especially deeply in places. For example, Herakles’s right arm is fully free of the metope’s background. The narrative focus here is not on the labor itself, but instead on the interaction between the successful hero, Herakles, and his patron goddess, Athena.

West metope 4 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble, 1.6 x 1.6 m (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Joanbanjo, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In contrast, the next metope is full of action. Here, we see Herakles in the midst of capturing the destructive Cretan Bull. Both Herakles and the bull are rendered with an extreme attention to naturalism. As the bull rears up and towards the viewer’s right, he turns his head backwards to look at the hero. The animal’s head projects fully from the background of the metope. Herakles tries to counteract the force of the bull by pulling back, towards the left. His muscles visibly strain beneath his torso and his gaze is directed straight at his opponent. Herakles and the bull move in opposite directions, countering each other and crossing over one another, creating a composition that is full of tension. [24]

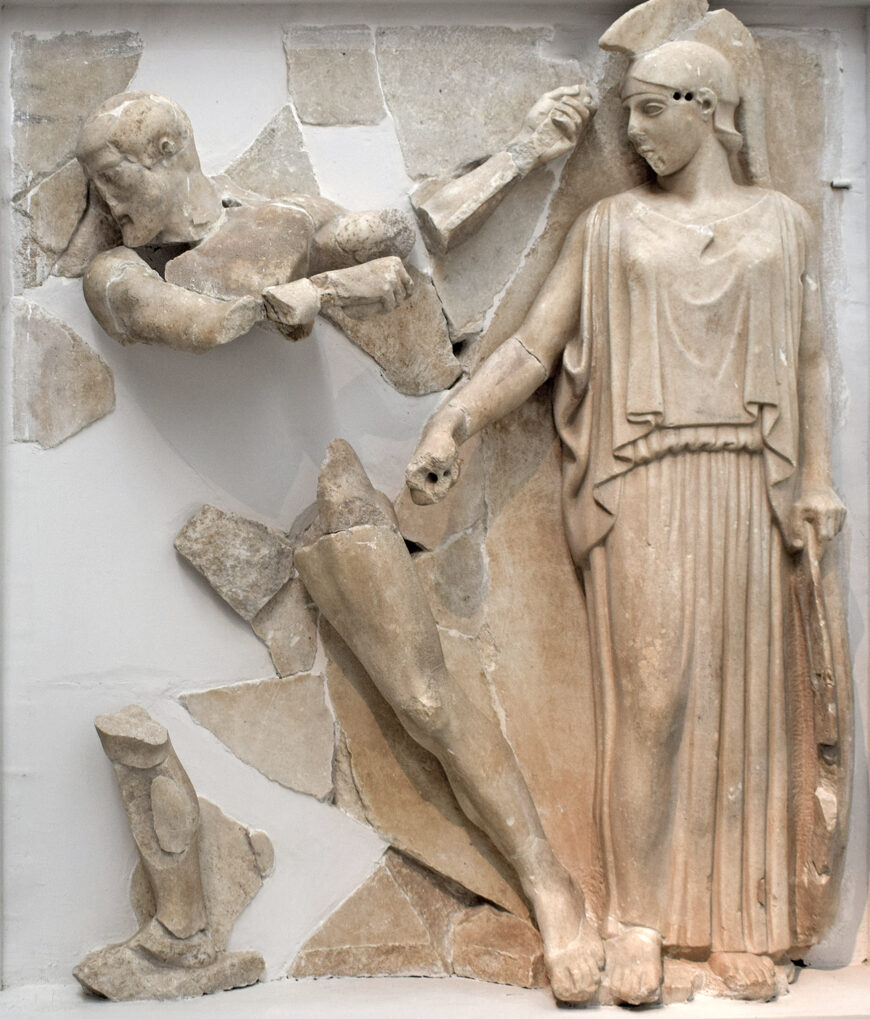

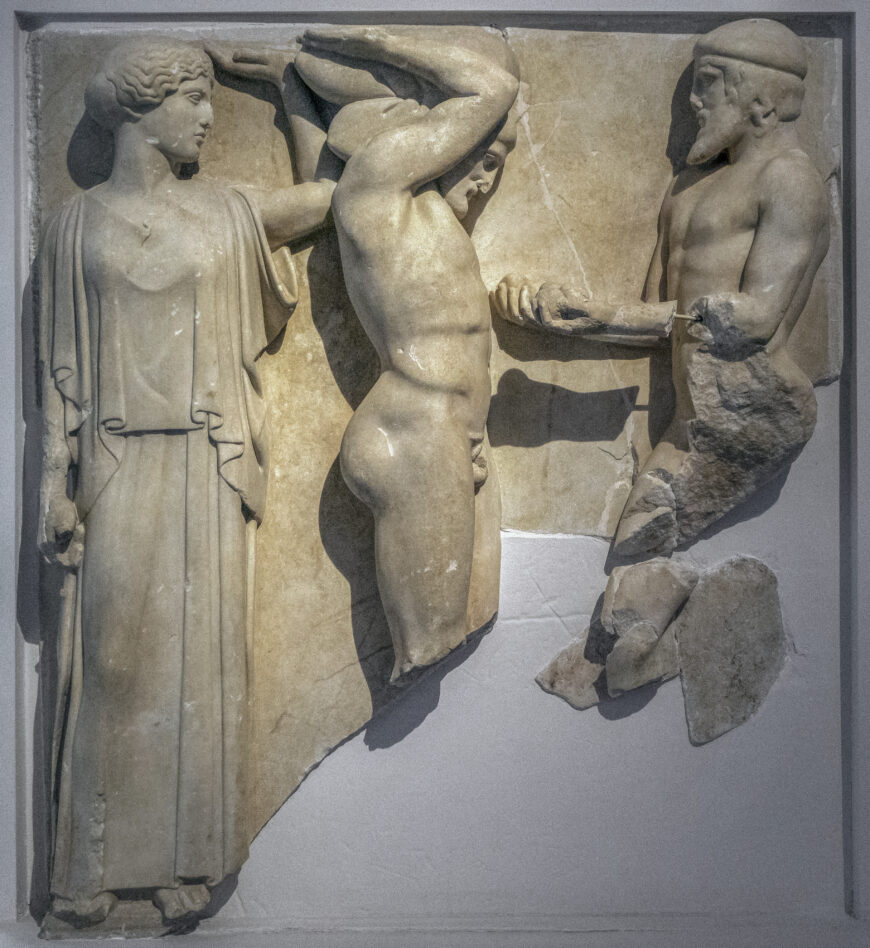

East metope 4 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble, 1.6 x 1.6 m (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The fourth metope on the east side of the temple depicts one of Herakles’s last labors. Herakles was asked to steal golden apples from the Garden of the Hesperides. When he arrived at the garden, Herakles encountered Atlas, an old god who was forced to hold up the heavens for all of eternity after losing a battle against Zeus and the other Olympian gods. Herakles asked Atlas to retrieve the golden apples for him, offering to hold up the sky in his absence. In this metope we see the moment Atlas returns from the Garden of the Hesperides, with the golden apples in his hands, as Herakles supports the sky with the help of Athena.

Although there is no exaggerated motion in this relief, there is still plenty of tension. Despite his immense strength, Herakles struggles under the enormous weight of the skies. He uses both arms (and a cushion on his shoulders) to hold up heaven. He looks down in a posture that suggests great strain, and his torso bends back as he engages all his muscles. By contrast, Athena shows no struggle at all. She casually places one palm flat up against the burden of the sky, effortlessly helping Herakles. Through her heavy drapery, we can see that she is standing with her weight on her left leg while her right leg bends free, apparently relaxed in spite of the weight she bears. This contrast reminds us that the impressive strength of the hero Herakles is still less than the strength of the gods.

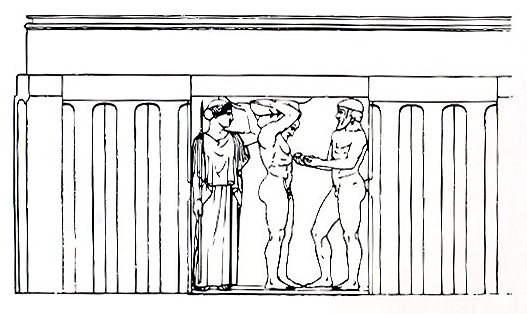

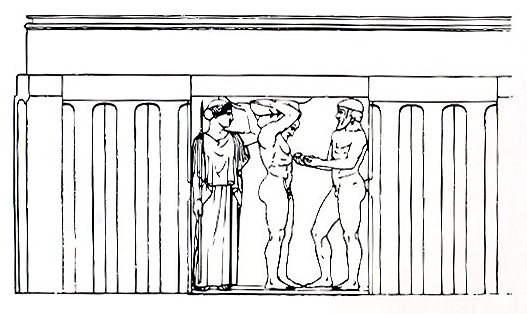

Reconstruction drawing of east metope 4 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia between triglyphs

Another innovation makes this metope even more interesting. When it was positioned on the temple, it would have been situated between two triglyphs, directly beneath another course of stone. In this context, it would look as if the load Herakles and Athena carried was the temple’s superstructure itself. Ancient viewers would immediately recognize the story being told here, but its clever incorporation into its architectural context would provide an unexpected twist that might have provoked conversation. The designers of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia intentionally played with some of the metopes’ positions on the temple, integrating them into the building in new ways. [25]

East metope 6 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble, 1.6 x 1.6 m (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Jean Housen, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The last metope on the east side of the temple depicts one of Herakles’s less popular labors. This labor was first described in ancient literature in 476 B.C.E., only 6 years before construction on the temple began, and, to the best of our knowledge, had never before been depicted in Greek art. [26] In this particularly unpleasant labor, Herakles was asked to clean the stables owned by a king named Augeas. Although these stables were home to hundreds of cattle, they had not been cleaned in decades, leaving Herakles with the foul task of scooping out an unimaginable amount of cattle dung. To complete this labor, Herakles re-routed two entire rivers so that they would run through the stables and wash them clean.

The metope shows Herakles as he changes one of the river’s paths. He is mid-swing, about to drive his tool into the ground to reshape the water’s flow. In its original position on the temple, it would look as though Herakles was about to drive his tool into the neighboring triglyph and pry it off. Athena stands beside him, wearing her heavy dress and her helmet. Her presence indicates her support of Herakles, though once again she appears in a relaxed posture that contrasts with Herakles’s strenuous motion.

The sculptors’ decision to include the story of the Augean Stables in their series of metopes was an ingenious one. Legend tells us that one of the rivers that Herakles re-routed was the Alpheios River, a large waterway that flows through the Peloponnese, close to the sanctuary at Olympia. Once again, we see that the artisans who designed the architectural sculpture of the Temple of Zeus chose narratives that were especially relevant to their context. The great hero Herakles, who eventually became a god in part because of his great strength, was a popular figure amongst all ancient Greeks and a role model for the athletes who competed in the Olympic Games. Working in the Early Classical style, the sculptors made metopes that showed off Herakles’s physicality. Their work celebrates the achievements of this heroic son of Zeus and pointedly incorporates them into the temple’s structure and the sanctuary.

Site plan of the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia, with Pheidias’s workshop and the Temple of Zeus highlighted

Cult statue

Almost 30 years after the Temple of Zeus and its rich decorations were completed, sanctuary officials decided to add one more element to the structure. They hired Pheidias, the master sculptor who had recently created the cult statue of Athena Parthenos that stood in the Parthenon in Athens, to create a cult statue of Zeus for his temple at Olympia. Archaeologists have discovered the workshop Pheidias used while building his enormous gold and ivory statue of Zeus just behind the temple.

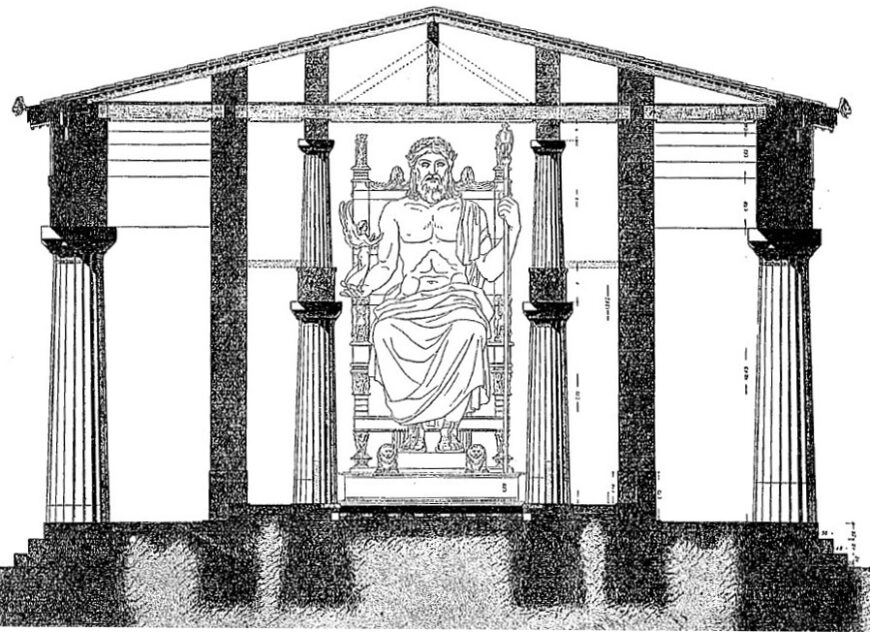

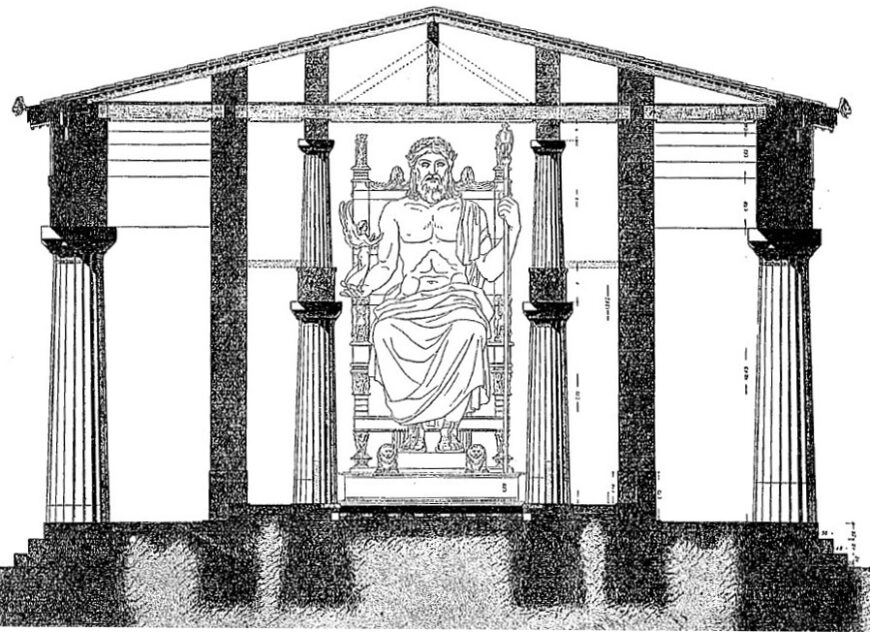

Reconstruction drawing of the statue of the Zeus within the Temple of Zeus at Olympia by Hermann Luckenbach, c. 1904

Pheidias’s statue of Zeus does not survive today, but ancient depictions and written descriptions of the image give us a sense of what it looked like. The statue was so large that the columns inside the Temple of Zeus had to be taken down and moved further apart to fit it. [27] Modern scholars who have converted ancient measurements of the statue suggest that the statue’s total height, including its base, was some 13.3 meters (43.64 feet), and that the base was about 6.6 meters (21.65 feet) wide. [28] The immense size of the statue, as well as the expensive materials of which it was made, would have made it even more awesome for ancient visitors to the temple.

Reverse of a coin minted under Antiochus IV Epiphanes in Syria, c. 175–164 B.C.E., gold. The coin seems to show the Olympian Zeus, seated on a throne, holding a scepter in his left hand and a Nike on his right hand (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Zeus was shown seated on a throne that was elaborately decorated with a number of mythical scenes. He held a small Nike in the palm of one hand and grasped a scepter with the other. He was shown with his chest and arms bare, while a cloak wrapped around the rest of his body. Pheidias’s decision to represent Zeus with a bare chest showed off the god’s physical perfection and emphasized the great cost of the statue, as his skin was made of ivory, a hugely expensive imported material. [29] The impressiveness of this statue of Zeus within the temple at Olympia is further indicated by the fact that it was considered one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

This cult statue was the final addition to an already spectacular temple. Libon of Elis designed the temple, a Doric structure of great scale, to act as a focal point of worship in the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia. His sculptors decorated it with images, both in the pediments and on the metopes. These sculptures tell stories of Greek triumphs, many of which are especially relevant to their Olympic, and more broadly, Peloponnesian context. It is probable that only a select few worshippers would have been allowed inside the temple, but even those who were not able to enter the temple would be able to view its rich exterior decoration. The Temple of Zeus, its decorations, and the cult statue that sat within it would have encouraged all visitors to the sanctuary at Olympia to consider the heroism and artistic prowess of the Greeks.

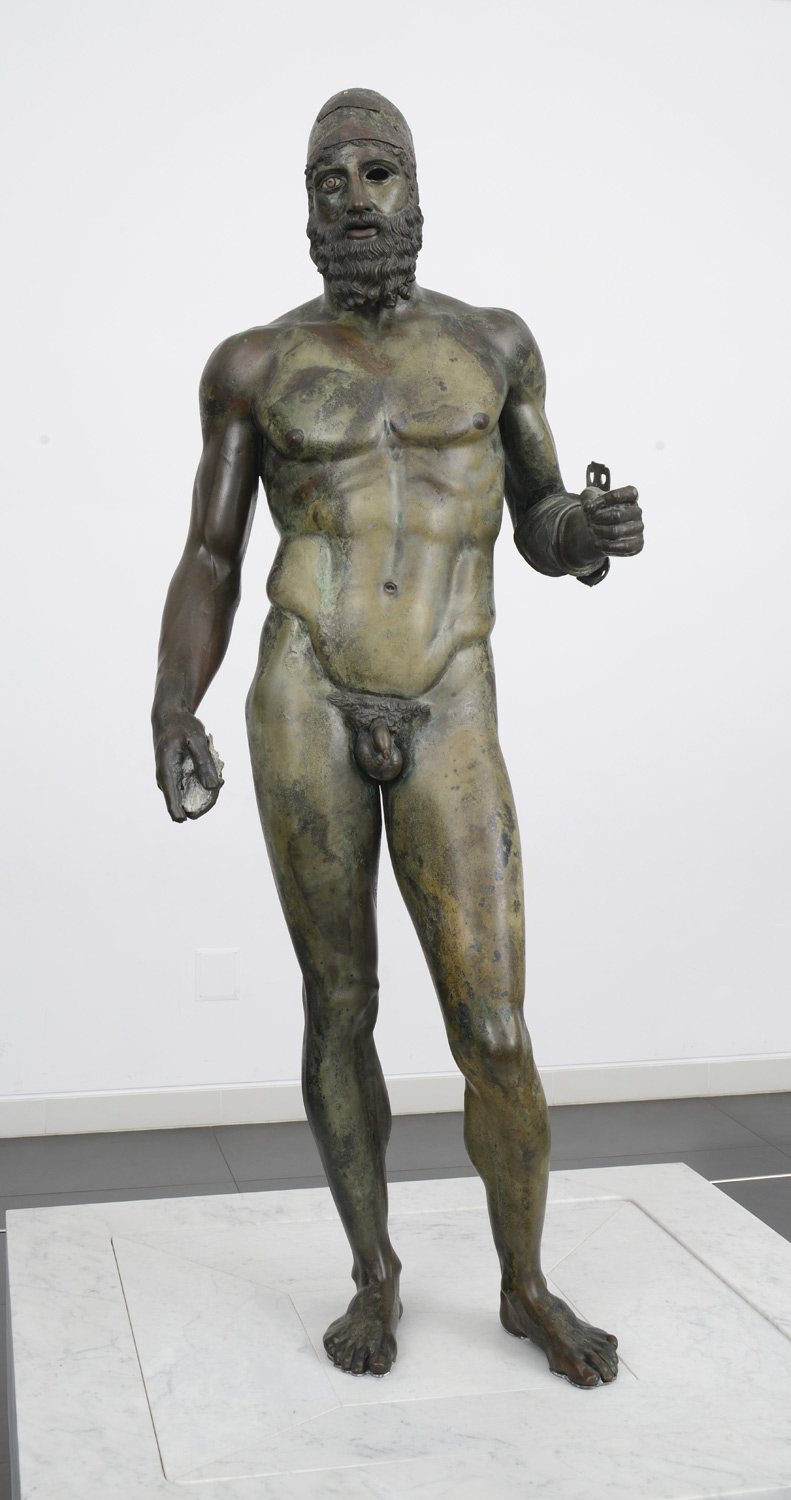

The Artemision Bronze represents either Zeus or Poseidon. Both gods were represented with full beards to signify maturity. However, it is impossible to identify the sculpture as one god or the other because it can either be a lightning bolt (symbolic of Zeus) or a trident (symbolic of Poseidon) in his raised right hand. The figure stands in heroic nude, as would be expected with a god, with his arms outstretched, preparing to strike. The bronze is in the severe style with an idealized, muscular body and an expressionless face. Like the Charioteer and the Riace Warriors, the Artemision Bronze once held inlaid glass or stone in its now-vacant eye sockets to heighten its lifelikeness. The right heel of the figure rises off the ground, which anticipates the motion the figure is about to undertake. The full potential of the god’s motion and energy, as well as the grace of the body, is reflected in the modelling of the bronze.

The discovery of the statues in 1972 (photo: MM)

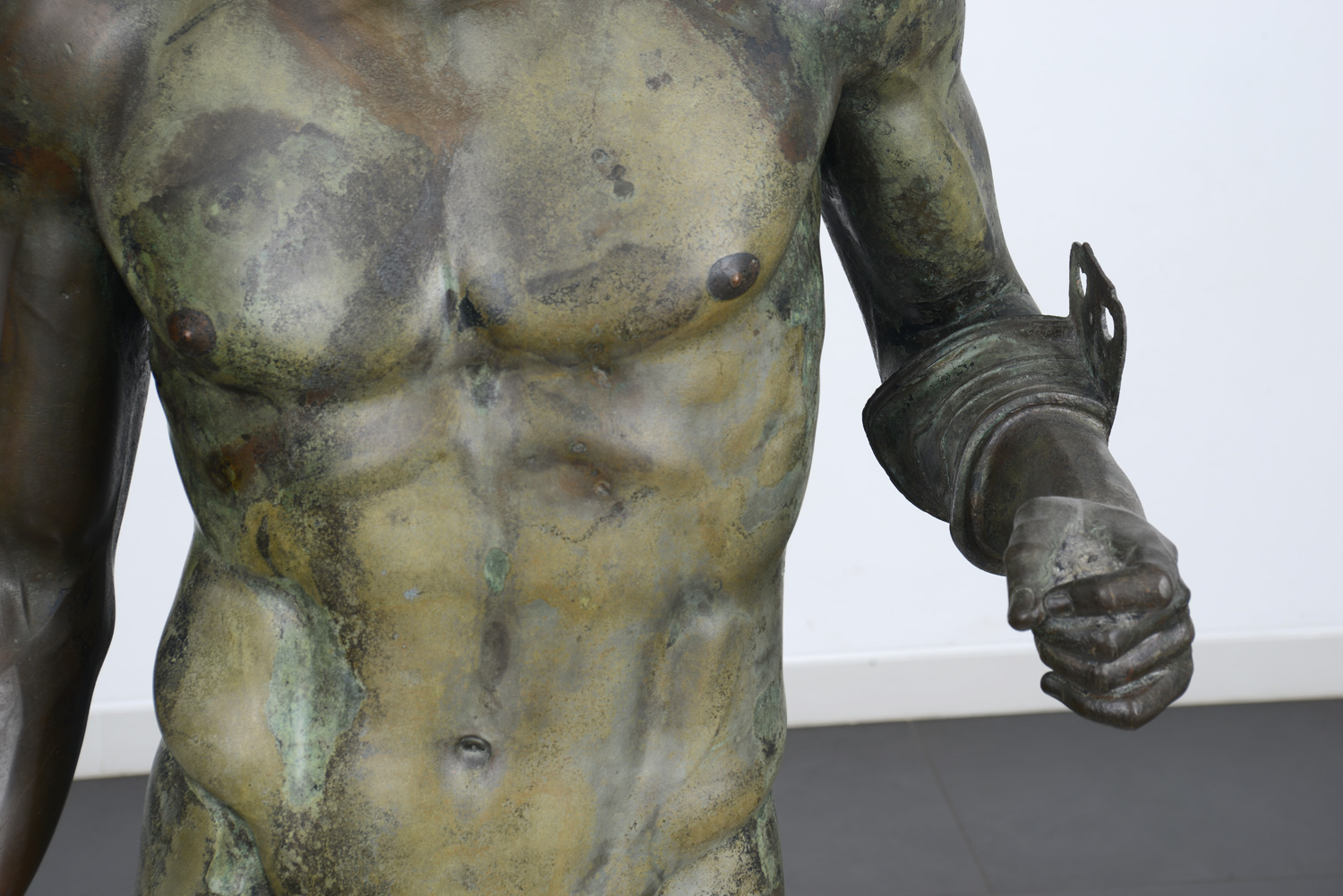

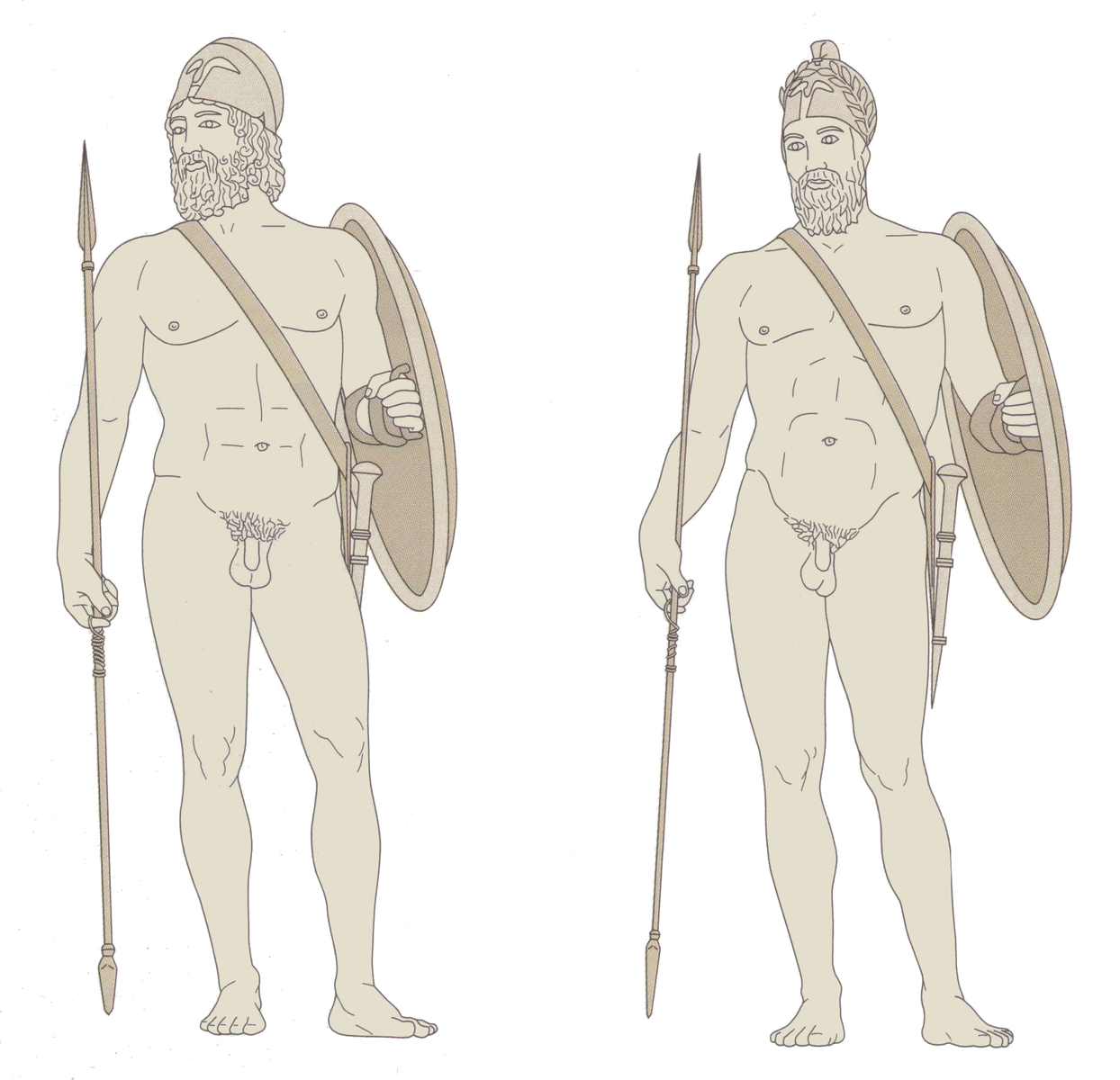

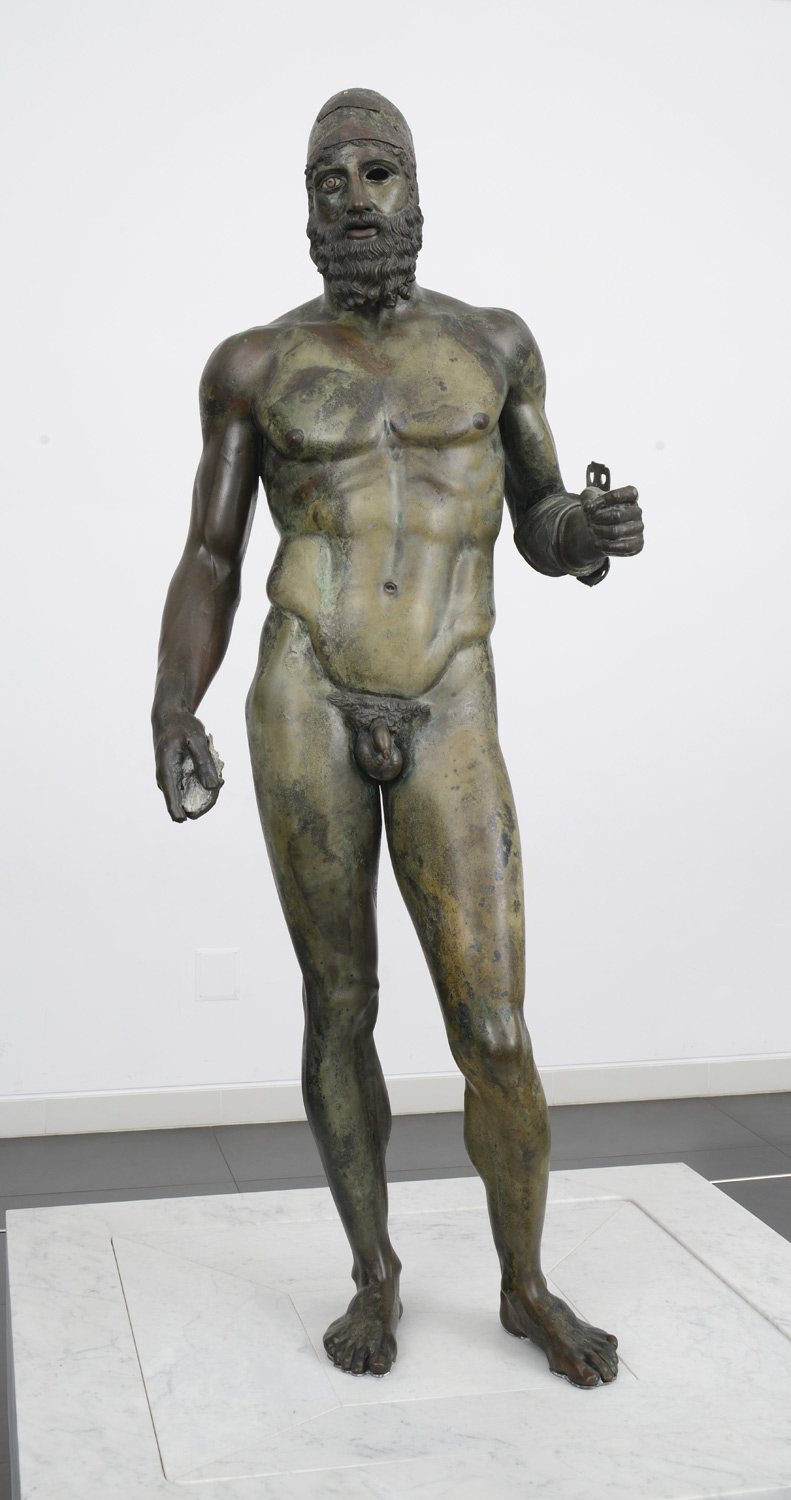

The Riace Warriors (also referred to as the Riace bronzes or Bronzi di Riace) are two life-size Greek bronze statues of naked, bearded warriors. The statues were discovered by Stefano Mariottini in the Mediterranean Sea just off the coast of Riace Marina, Italy, on August 16, 1972. The statues are currently housed in the Museo Nazionale della Magna Grecia in the Italian city of Reggio Calabria. The statues are commonly referred to as “Statue A” and “Statue B” and were originally cast using the lost-wax technique.

Statue A

Statue A stands 198 centimeters tall and depicts the younger of the two warriors. His body exhibits a strong contrapposto stance, with the head turned to his right. Attached elements have been lost—most likely a shield and a spear; his now-lost helmet atop his head may have been crowned by a wreath. The warrior is bearded, with applied copper detail for the lips and the nipples. Inset eyes also survive for Statue A. The hair and beard have been worked in an elaborate fashion, with exquisite curls and ringlets.

Statue B, from the sea off Riace, Italy, c. 460–50 B.C.E. (?), bronze, 197 cm high (Museo Archeologico Nazionale Reggio Calabria)

Statue B

Statue B depicts an older warrior and stands 197 centimeters tall. A now-missing helmet likely was perched atop his head. Like Statue A, Statue B is bearded and in a contrapposto stance, although the feet of Statue B and set more closely together than those of Statue A.

Severe style

The Severe or Early Classical style describes the trends in Greek sculpture between c. 490 and 450 B.C.E. Artistically this stylistic phase represents a transition from the rather austere and static Archaic style of the sixth century B.C.E. to the more idealized Classical style. The Severe style is marked by an increased interest in the use of bronze as a medium as well as an increase in the characterization of the sculpture, among other features.

Interpretation and chronology

The chronology of the Riace warriors has been a matter of scholarly contention since their discovery. In essence there are two schools of thought—one holds that the warriors are fifth century B.C.E. originals that were created between 460 and 420 B.C.E., while another holds that the statues were produced later and consciously imitate Early Classical sculpture. Those that support the earlier chronology argue that Statue A is the earlier of the two pieces. Those scholars also make a connection between the warriors and the workshops of famous ancient sculptors. For instance, some scholars suggest that the sculptor Myron crafted Statue A, while Alkamenes created Statue B. Additionally, those who support the earlier chronology point to the Severe Style as a clear indication of an Early Classical date for these two masterpieces.

The art historian B. S. Ridgway presents a dissenting view, contending that the statues should not be assigned to the fifth century B.C.E., arguing instead that they were most likely produced together after 100 B.C.E. Ridgway feels that the statues indicate an interest in Early Classical iconography during the Hellenistic period.

In terms of identifications, there has been speculation that the two statues represent Tydeus (Statue A) and Amphiaraus (Statue B), two warriors from Aeschylus’ tragic play, Seven Against Thebes (about Polyneices after the fall of his father, King Oedipus), and may have been part of a monumental sculptural composition. A group from Argos described by Pausanias (the Greek traveler and writer) is often cited in connection to this conjecture: “A little farther on is a sanctuary of the Seasons. On coming back from here you see statues of Polyneices, the son of Oedipus, and of all the chieftains who with him were killed in battle at the wall of Thebes…” [1]

The statues have lead dowels installed in their feet, indicating that they were originally mounted on a base and installed as part of some sculptural group or other. The art historian Carol Mattusch argues that not only were they found together, but that they were originally installed—and perhaps produced—together in antiquity.

Notes:

[1] Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.20.5.

Cite this page as: Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker, “Riace Warriors,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed May 29, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/riace-warriors/.