Part man, part goat, this companion of the god of wine relaxes after a night of drinking.

Barberini Faun, c. 220 B.C.E., Hellenistic Period (Glyptothek, Munich)

Historians today consider the death of Alexander to be the end point of the Classical Period and the beginning of the Hellenistic Period. That moment, for historians, also marks the end of the polis as the main unit of organization in the Greek world. While city-states continued to exist, the main unit of organization from that point on was the great Hellenistic kingdoms. These kingdoms, encompassing much greater territory than the Greek world had before Alexander, contributed to the thorough Hellenization of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. The age of the Hellenistic kingdoms also coincided with the rise of Rome as a military power in the West. Ultimately, the Hellenistic kingdoms were conquered and absorbed by Rome.

Although Alexander had several children from his different wives, he did not leave an heir old enough to take power upon his death. Indeed, his only son, Alexander IV, was only born several months after his father’s death. Instead, Alexander’s most talented generals turned against each other in a contest for the control of the empire that they had helped create.

.png?revision=1)

: Map of the Initial partition of Alexander’s empire, before the Wars of the Diadochi (CC BY-SA 3.0; User “Fornadan” via Wikimedia Commons)

These Wars of the Diadochi, as they are known in modern scholarship, ended with a partition of Alexander’s empire into a number of kingdoms, each ruled by dynasties. Of these, the four most influential dynasties which retained power for the remainder of the Hellenistic Age, were the following: Seleucus, who took control of Syria and the surrounding areas, thus creating the Seleucid Empire; Antigonus Monophthalmos, the One-Eyed, who took over the territory of Asia Minor and northern Syria, establishing the Antigonid Dynasty; the Attalid Dynasty, which took power over the Kingdom of Pergamon, after the death of its initial ruler, Lysimachus, a general of Alexander; and Ptolemy, Alexander’s most influential general, who took control over Egypt, establishing the Ptolemaic Dynasty.

The most imperialistic of Alexander’s successors, Seleucus I Nicator took Syria, swiftly expanding his empire to the east to encompass the entire stretch of territory from Syria to India. At its greatest expanse, this territory’s ethnic diversity was similar to that of Alexander’s original empire, and Seleucus adopted the same policy of ethnic unity as originally practiced by Alexander; some of Seleucus’ later successors, however, attempted to impose Hellenization on some of the peoples under their rule. These successors had difficulties holding on to Seleucus’ conquests. A notable exception, Antiochus III, attempted to expand the Empire into Anatolia and Greece in the early second century BCE but was ultimately defeated by the Romans. The empire’s story for the remainder of its existence is one of almost constant civil wars and increasingly declining territories. The Seleucids seem to have had a particularly antagonistic relationship with their Jewish subjects, going so far as to outlaw Judaism in 168 BCE. The Jewish holiday Hannukah celebrates a miracle that occurred following the historical victory of the Jews, led by Judah Maccabee, over the Seleucids in 165 BCE. Shortly afterwards, the Seleucids had to allow autonomy to the Jewish state; it achieved full independence from Seleucid rule in 129 BCE. In 63 BCE, the Roman general Pompey finally conquered the small remnant of the Seleucid Empire, making it into the Roman province of Syria.

.png?revision=1)

: Map of the Hellenistic Kingdoms c. 303 BCE (Public Domain; User “Javierfv1212” via Wikimedia Commons)

Antigonus Monophthalmos, Seleucus’ neighbor, whose holdings included Macedonia, Asia Minor, and the northwestern portion of Syria, harbored ambitious plans that rivaled those of Seleucus. Antigonus’ hopes of reuniting all of Alexander’s original empire under his own rule, however, were never realized as Antigonus died in battle in 301 BCE. The greatest threat to the Antigonids, however, came not from the Seleucid Empire, but from Rome with whom they waged three Macedonian Wars between 214 and 168 BCE. The Roman defeat of king Perseus in 168 BCE at the Battle of Pydna marked the end of the Third Macedonian War, and the end of an era, as control over Greece was now in Roman hands.

The smallest and least imperialistic of the successor states, the kingdom of Pergamon, was originally part of a very short-lived empire established by Lysimachus, one of Alexander’s generals. Lysimachus originally held Macedonia and parts of Asia Minor and Thrace but had lost all of these territories by the time of his death in 281 BCE. One of his officers, Philetaerus, however, took over the city of Pergamon, establishing there the Attalid dynasty that transformed Pergamon into a small and successful kingdom. The final Attalid king, Attalus III, left his kingdom to Rome in his will in 133 BCE.

Lasting from the death of Alexander in 323 BCE to the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE, the Ptolemaic kingdom proved to be the longest lasting and most successful of the kingdoms carved from Alexander’s initial empire. Its founder, Ptolemy I Soter, was a talented general, as well as an astronomer, philosopher, and historian, who wrote his own histories of Alexander’s campaigns. Aiming to make Alexandria the new Athens of the Mediterranean, Ptolemy spared no expense in building the Museaum, an institution of learning and research that included, most famously, the Great Library, and worked tirelessly to attract scholars and cultured elite to his city. Subsequent Ptolemies continued these works so that Alexandria held its reputation as a cultural capital into Late Antiquity. One example of a particularly impressive scientific discovery is the work of Eratosthenes, the head librarian at the Great Library in the second half of the third century BCE, who accurately calculated the earth’s circumference. But while the Ptolemies brought with them Greek language and culture to Egypt, they were also profoundly influenced by Egyptian customs. Portraying themselves as the new Pharaohs, the Ptolemies even adopted the Egyptian royal custom of brother-sister marriages, a practice that eventually percolated down to the general populace as well. Unfortunately, brother-sister marriages did not prevent strife for power within the royal family. The last of the Ptolemaic rulers, Cleopatra VII, first married and ruled jointly with her brother Ptolemy XIII. After defeating him in a civil war, she then married another brother, Ptolemy XIV, remaining his wife until his death, possibly from sisterly poisoning. Best known for her affairs with Julius Caesar and, after Caesar’s death, with Marcus Antonius, Cleopatra teamed with Marcus Antonius in a bid for the Roman Empire. The last surviving ruler who was descended from one of Alexander’s generals, she was finally defeated by Octavian, the future Roman emperor Augustus, in 30 BCE.

The history of the successor states that resulted from the carving of Alexander’s empire shows the imperialistic drive of Greek generals, while also demonstrating the instability of their empires. Historians do not typically engage in counter-factual speculations, but it is very likely that, had he lived longer, Alexander would have seen his empire unravel, as no structure was really in place to hold it together. At the same time, the clash of cultures that Alexander’s empire and the successor states produced resulted in the spread of Greek culture and language further than ever before; simultaneously, it also introduced the Greeks to other peoples, thus bringing foreign customs—such as the brother-sister marriages in Egypt—into the lives of the Greeks living outside the original Greek world.

The Hellenistic kingdoms spread Greek language, culture, and art all over the areas of Alexander’s former conquests. Furthermore, many Hellenistic kings, especially the Ptolemies, were patrons of art and ideas. Thus the Hellenistic era saw the flourishing of art and architecture, philosophy, medical and scientific writing, and even translations of texts of other civilizations into Greek. The undisputed center for these advances was Alexandria.

This page titled 5.11: Hellenistic Period is shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Nadejda Williams (University System of Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials) via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform; a detailed edit history is available upon request.

Architecture during the Hellenistic period focused on theatricality and drama; the period also saw an increased popularity of the Corinthian order.

Architecture in the Greek world during the Hellenistic period developed theatrical tendencies, as had Hellenistic sculpture. The conquests of Alexander the Great caused power to shift from the city-states of Greece to the ruling dynasties . Dynastic families patronized large complexes and dramatic urban plans within their cities. These urban plans often focused on the natural setting, and were intended to enhance views and create dramatic civic, judicial, and market spaces that differed from the orthogonal plans of the houses that surrounded them.

Architecture in the Hellenistic period is most commonly associated with the growing popularity of the Corinthian order. However, the Doric and Ionic orders underwent notable changes. Examples include the slender and unfluted Doric columns and the four-fronted capitals on Ionic columns, the latter of which helped to solve design problems concerning symmetry on the temple porticos.

A key component of Hellenistic sculpture is the expression of a sculpture’s face and body to elicit an emotional response from the viewer.

Hellenistic sculpture continues the trend of increasing naturalism seen in the stylistic development of Greek art. During this time, the rules of Classical art were pushed and abandoned in favor of new themes, genres , drama, and pathos that were never explored by previous Greek artists.

Furthermore, the Greek artists added a new level of naturalism to their figures by adding an elasticity to their form and expressions, both facial and physical. These figures interact with their audience in a new theatrical manner by eliciting an emotional reaction from their view—this is known as pathos.

Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

The Hellenistic Period is shared under a not declared license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

The Barberini Faun, also known as the Sleeping Satyr (c. 220 BCE), depicts an effeminate figure, most likely a satyr, drunk and passed out on a rock. His body splays across the rock face without regard to modesty.

He appears to have fallen to sleep in the midst of a drunken revelry and he sleeps restlessly, his brow is knotted, face worried, and his limbs are tense and stiff. Unlike earlier depicts of nude men, but in a similar manner to the Venus de Milo, the Barberini Faun seems to exude sexuality.

Barberini Faun: This is a Roman marble copy, in Rome, Italy, of the Greek bronze original, c. 220 BCE. Italy.

Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

The Hellenistic Period is shared under a not declared license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

Part man, part goat, this companion of the god of wine relaxes after a night of drinking.

Barberini Faun, c. 220 B.C.E., Hellenistic Period (Glyptothek, Munich)

Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, "Barberini Faun," in Smarthistory, December 9, 2015, accessed May 30, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/barberini-faun/.

Pergamon rose as a power under the Attalids and provides examples of the drama and theatrics found in Hellenistic art and architecture.

The ancient city of Pergamon, now modern day Bergama in Turkey, was the capital of the Kingdom of Pergamon following the death of Alexander the Great and was ruled under the Attalid dynasty . The Acropolis of Pergamon is a prime example of Hellenistic architecture and the convergence of nature and architectural design to create dramatic and theatrical sites.

The acropolis was built into and on top a steep hill that commands great views of the surrounding countryside. Both the upper and lower portions of the acropolis were home to many important structures of urban life, including gymnasiums, agorae, baths, libraries, a theater, shrines, temples, and altars.

Scale model of Pergamon as it might have looked in antiquity: Center left: Theatre of Pergamon. Center right: Altar of Zeus. Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

The theater at Pergamon could seat 10,000 people and was one of the steepest theaters in the ancient world. Like all Hellenic theaters, it was built into the hillside, which supported the structure and provided stadium seating that would have overlooked the ancient city and its surrounding countryside. The theater is one example of the creation and use of dramatic and theatrical architecture.

Theater of Pergamon: The theater at Pergamon could seat 10,000 people and was one of the steepest theaters in the ancient world.

Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

The Hellenistic Period is shared under a not declared license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

The Pergamon Altar, c. 200-150 B.C.E., 35.64 x 33.4 meters, Hellenistic Period (Pergamon Museum, Berlin); speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Acropolis, Pergamon, İzmir Province, Turkey (photo: Carol Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

But Ge [goddess of earth] . . . brought forth the giants, whom she had by Uranus [god of the sky]. These were matchless in the bulk of their bodies and invincible in their might; terrible of aspect did they appear, with long locks drooping from their head and chin, and with the scales of dragons for feet.—Apollodorus, Library 1.6.1

Pergamon Altar (today in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin, photo: Garret Ziegler, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Battle between the Gods and Giants (detail), Krater with Gigantomacy scene, classical period, Ancient Greece (Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid)

The ancient Greeks represented the mythological battle between the Olympian gods and the giants in a wide variety of media—from miniature engraved gemstones and vase paintings, to over-life-sized architectural sculptures.

Perhaps the most famous and well-preserved of these decorates the Pergamon Altar. The Altar once stood in a sacred precinct on the acropolis of the ancient city of Pergamon (on the west coast of modern-day Turkey), which was ruled by the Attalid dynasty from 282–133 B.C.E.

In comparison to other Hellenistic kingdoms (kingdoms formed after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.E. and stretching from the eastern Mediterranean to Central Asia), Pergamon emerged relatively late on the scene. Monumental building projects—including the Altar—served as an important way for the Attalids to stake their claim as legitimate inheritors of Alexander’s empire and, by extension, the legacy of Classical Greece.

In the early 20th century the Altar found a new home in Berlin, Germany—2,677 kilometers from its original location—where it has remained on view since 1930 as the centerpiece of the museum bearing its name (see end note below and learn more here about how the altar ended up in Berlin). [1]

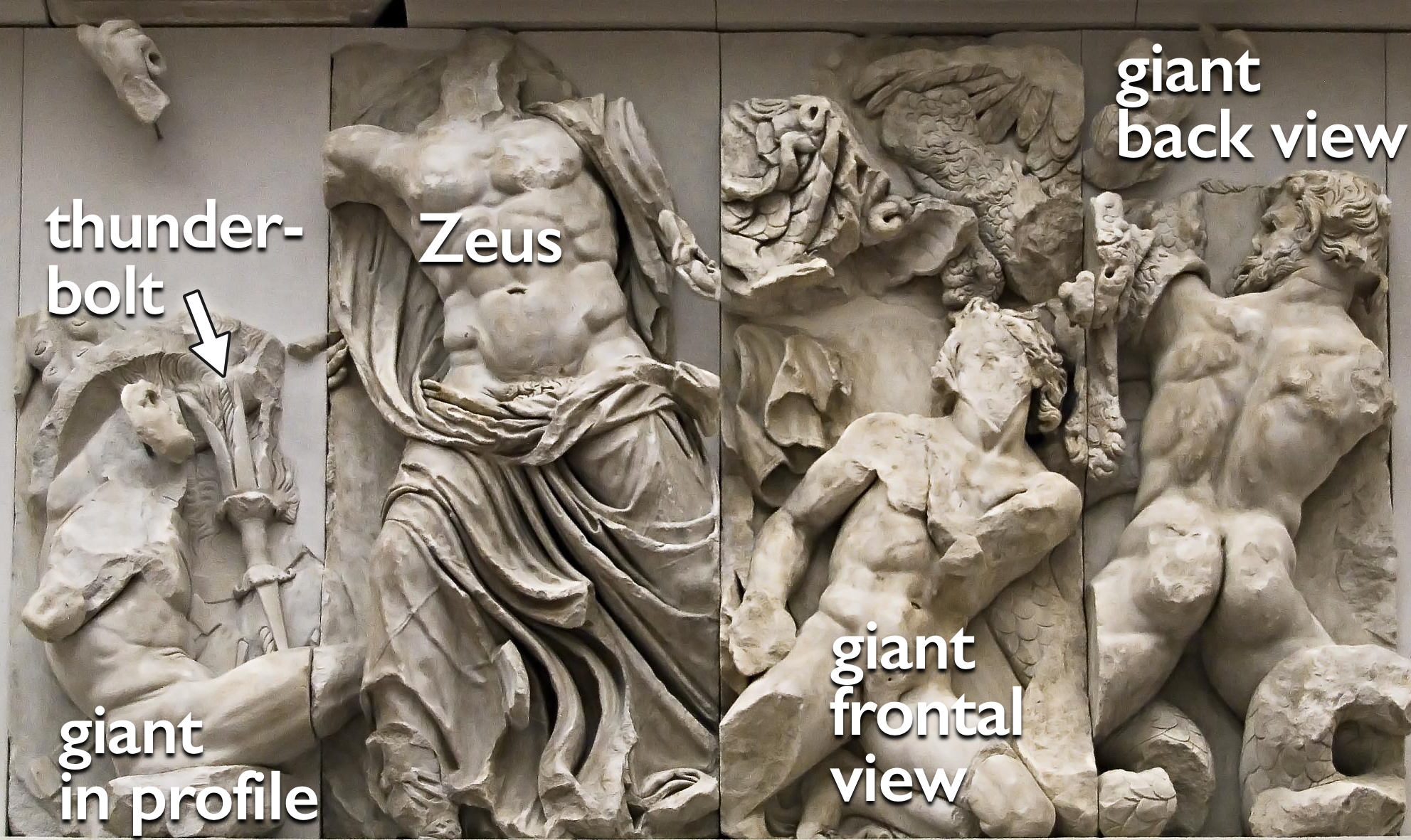

The Altar’s architectural framework alone is impressive—it comprises a monumental Π-shaped structure surrounded by columns and accessed by a grand staircase. However, its most eye-catching feature is undoubtedly the frieze, a massive 113 meters long and 2.3 meters high marble high-relief that wraps around the building’s entire exterior and depicts the mythological battle between the Gods of Mount Olympus and Giants.

The battle, known as the gigantomachy—from the ancient Greek γίγαντες (“giants”) and μάχη (“battle”)—represented a crucial shift for the ancient Greeks: the old religion, which was rooted in the natural world (for example, Ge, the earth goddess and mother of the giants), was overthrown by the new, civilized order of the Olympian gods (for example, Zeus, Athena, and others). According to the myth, the gods received a prophecy that the giants could only be defeated with the help of a mortal. Zeus (assisted by Athena), called upon the hero Herakles who dealt the decisive blow by shooting them with arrows. [2] Over time, the visual tradition of the gigantomachy expanded to include the presence of other Greek heroes, who also aided the gods.

The approach

Ancient viewers would have first approached the Altar from its rear, where the gigantomachy’s main protagonists—the god Zeus and goddess Athena assisted by the hero, Herakles—decisively defeat their giant antagonists. From this view, the figures in the relief appear inaccessible as they tower above—their over-life-sized bodies often twisting into near-impossible positions in the midst of battle. While the stepped platform made it possible to access the frieze up close, this would only have placed viewers in uncomfortable proximity to the immortal skirmish.

From left to right, figures associated with water: Nereus and Doris, Oceanos, and part of Tethys(?). North side of grand staircase, Pergamon Altar (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The sides of the altar

As visitors continued along either side of the Altar they encountered gods and goddesses thematically assembled (for example, the twin gods Apollo and Artemis with their mother Leto). Despite the Altar’s fragmentary state of preservation, many of the figures can be identified—now, as in ancient times—through inscriptions included above (in the case of the gods) and below (in the case of the giants) the frieze.

From left to right, figures associated with water: Nereus and Doris, Oceanos, and part of Tethys(?). Giants kneel further to the right. North side of grand staircase, Pergamon Altar (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Front of the Altar

Once ancient viewers reached the Altar’s front the characters began to increasingly invade their space, projecting outwards to the point where some giants (such as those battling water divinities on the north side) even kneel on the steps. It’s as if they are inviting us to join the terrifying conflict as we ascend. Despite the immense number of figures on the frieze, each panel manages to offer new discoveries for its viewers.

This version of the gigantomachy is characteristic of the Hellenistic style (Greek art dating from c. 323 to 31 B.C.E.). It is highly dramatic, both in terms of the overtly exaggerated dynamism of the figures’ bodily positions and the pathos exhibited by their expressions. The frieze, and its enigmatic central characters, first draw viewers in via the two central panels featuring the god Zeus and the goddess Athena.

The goddess Athena grasps the giant Alkyoneos by his unruly wavy hair, pulling his face to the left. His right arm grasps in vain at Athena’s forearm. A serpent, the agent of Athena, restrains the giant’s body and simultaneously exposes his anatomy to the viewer. Alkyoneos kneels on his right leg, while his left leg extends outwards, crossing over Athena’s striding form. His face, with its wrinkled brow and open mouth, exaggerates his suffering. It is framed by the interlocked arms of giant and goddess as well as by the giant’s wings, which fill the top of the panel in low relief. Ge, goddess of the earth and mother of giants, emerges from the ground to beg for her son’s life. Notably, the earth goddess is the only figure to be identified with an inscription on the frieze itself (rather than above or below, as with the other gods and giants) emphasizing her role as an intermediary. Nevertheless, Nike, goddess of Victory, has already flown in to crown Athena, sealing Alkyoneos’ fate.

The giants from the Zeus panel are rendered from three distinct perspectives. One, directly to Zeus’ left, kneels on his left leg, his body not nearly as extended as Athena’s opponent. A second, furthest from Zeus, shows us his muscular back, buttocks, and serpentine legs as he turns toward the god with his bearded face in profile. The third, to Zeus’ right, has been pierced by Zeus’ weapon, the thunderbolt, and sits in profile view, wounded on the ground. Although barely preserved, just to the right of this wounded giant the figure of Herakles can be detected by a paw from the Nemean lion’s skin (an attribute of the Greek hero Herakles). Herakles’ essential role in the gigantomachy has been appropriately emphasized through his proximity to Zeus. (In fact, the Attalid’s choice to monumentalize this particular myth was likely tied to the presence of the Greek hero who was the father of Telephos, the mythological founder of Pergamon).

Just as impressive as their dynamic poses, these two panels depict a diversity of giant types—from human to animal. On the Altar, a giant could be fully humanized, and even wear armor. But many more are anguiform (snake-like) and some possess further animalistic features. A few, besides, are even more overtly animal-like, almost monstrous.

Detail of the north frieze showing the god Apollo and goddess Artemis advancing towards a fleeing giant, Siphnian Treasury, c. 530 B.C.E., Sanctuary of Apollo, Delphi, Greece (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Some of the earliest representations of the gigantomachy, such as the frieze from the Treasury of the Siphnians at Delphi (c. 525 B.C.E.), appear to follow Hesiod’s Theogony, in which he describes the giants as born wearing “gleaming armor with long spears in their hands.” [3] For example, a detail from the north frieze shows the god Apollo and goddess Artemis advancing towards a fleeing giant, who turns back to look at them. The Archaic-style giants are uniformly depicted in armor (similar to the that worn by hoplites, the foot soldiers of ancient Greece) and face the gods almost as equals. To the left of this scene, a lion—pulling a goddess’s chariot—attacks a giant. The frieze is dominated by overlapping profiles of gods and giants who stride toward one another but there is little indication of physical engagement between the figures, save for the lion and the giant.

East metopes showing a portion of the gigantomachy, Iktinos and Kallikrates, Parthenon, Acropolis, Athens, 447–432 B.C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Over time and in countless artworks, artists reimagined the gigantomachy to include a variety of characters, interactions, and attributes, eventually making the Pergamon Altar version possible. One of the most recognized examples of the gigantomachy, on the east metopes of the Parthenon (447–438 B.C.E.), promoted the Athenians as civilizers and preservers of Greek culture over the barbarous Persian forces. Following the Persian wars (545–448 B.C.E.) the attire of the giants changed to include animal skins (difficult to see on the metopes today). The Classical-style Parthenon metopes have evolved from the Archaic depictions of the Siphnian treasury to emphasize a clearer distinction between god and giant. The gods are generally portrayed above the giants; the giants have shed the majority of their hoplite armor in favor of donning animal skins and wielding rocks or clubs, which connect them to the natural world.

The Athenian Parthenon, and the city of Athens more broadly, became incredibly influential in both the Classical and later periods. Hellenistic rulers, including the Attalid kings of Pergamon, sought to emulate Athens and, significantly, forged visual connections between their own newly formed kingdoms and the established cities of mainland Greece. The Pergamene Acropolis contained numerous sculptural and architectural references to Athens, including an over life-sized marble copy of the colossal chryselephantine (gold and ivory) Athena Parthenos that once stood inside the Parthenon. The Altar too may have contained compositional allusions to the renowned Athenian temple, namely in the striding figures of Athena and Zeus, whose poses resemble that of Athena and Poseidon on its west pediment (see a reconstruction drawing of it here).

On the Parthenon, the Athenians used myths to provide commentaries on their contemporary reality. The barbaric giants, decisively defeated by the Olympian gods and assisted by Greek heroes, served as an appropriate visual metaphor for the Persians, who had desecrated the sacred sites of Greece including the Athenian Acropolis. Similarly, were the figures of giants on the Altar meant to evoke the enemies of Pergamon—the Gauls and the Macedonians?

Prior to the construction of the Altar, the first king of Pergamon, Attalos I, set up monuments to commemorate his victory over the Gauls and legitimize his rule. The fact that his sons (Eumenes II and Attalos II) also fought the Gauls has prompted scholars to consider the Great Altar as another victory monument.

Left: Wounded Gaul from the monument of Attalos I (Roman copy, c. 3rd–2nd century B.C.E. (Musée du Louvre) ; right: detail of Zeus’ opponent (a giant), Pergamon Altar, c. 1971–39 B.C.E. (Staatliche Museen, Berlin)

Single figures of Gauls from the earlier victory monuments that survive in the form of Roman copies bear clear resemblance to the giants from the Altar frieze. Compare the thick, curly, wild locks of hair of the Wounded Gaul in the Louvre to that of a giant from the Zeus panel. The Gauls were known to have covered their hair with a watered down plaster mixture, giving it a thickened rough appearance. [4] While the giants on the Altar were not exact quotations of the Gauls, their agonized twisting figures likely reminded viewers of the earlier monuments, some of which were probably erected nearby.

Left: Helmeted giant striding forward with shield; right: trampled giant with shield, Pergamon Altar, c. 197–139 B.C.E. (Staatliche Museen, Berlin)

The armored giants in the frieze evoke comparison with another contemporary adversary. Two giants from its east side—one striding toward the goddess Artemis bearing a shield, and a second trampled beneath Hera’s chariot, also holding a shield—bear characteristically Macedonian armor. The shield of the trampled giant is adorned with a starburst, a common emblem of the Macedonians. [5]

The Altar is not alone in alluding to victory of Pergamon over the Macedonians—images of their armor also appear at the Sanctuary of Athena, located just north of the Altar precinct on the Pergamene acropolis. The emphatic inclusion of these attributes may have served as a means to quash rumors that Eumenes II was considering peace or an alliance after the Third Macedonian War (172–168 B.C.E.), in which the Attalids had fought alongside the Romans. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the Altar—similar to other multifunctional structures in cities and sanctuaries throughout the Greek world—also served as a treasury for arms and armor captured in the Gallic and Macedonian wars (among others). These reminders—both real and sculpted—would have strengthened viewers’ visual associations between the enemies of Pergamon and the giants on the Altar frieze.

As ancient visitors traversed from the rear to the front of the Altar they witnessed the metamorphosis of giants from overtly monstrous anguiform and animal-headed representations to fully anthropomorphic figures equipped with the arms and armor of Attalid enemies. [6] Taking its cue from the example of the Classical Parthenon, the Pergamon Altar went one step further in encouraging its viewers to visually compare contemporary adversaries with the fearsome giants. Ultimately, in conflating a mythological battle with contemporary Attalid victories the Altar elevated the triumph of Pergamon to that of the gods.

End note

The Pergamene Acropolis was first rediscovered as early as the 14th century when Cyriacus of Ancona, an Italian antiquarian, visited the ruins. However, the site remained unexcavated until the late 19th century when the German engineer, Carl Humann, was commissioned by the Ottoman Empire to survey the area for a road-building project. Sultan Abdul Hamid II allowed the Germans a permit to fund their own excavations at Pergamon, where archaeologists have continued to work for the past 140 years under the aegis of the German Archaeological Institute and with the permission of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Turkey (for more information, see the Pergamon Excavation Project). Alexander Conze, director of the Berlin Antikensammlung (Collection of Classical Antiquities), oversaw the legal purchase and transport of the Altar, in its entirety, to Berlin, where it was first displayed in the Altes Museum until the Pergamon Museum was constructed. During World War II, the Altar was moved to a bunker for protection. At the conclusion of the war, the Soviet Union claimed the Altar and transferred it to St. Petersburg. It was eventually returned to Berlin in 1958. In the late 1990s, the Altar was part of a conversation about the repatriation of Turkish heritage. Since the modern Republic of Turkey was officially founded in 1923, the legality of some excavations and purchases conducted under the authority of the Ottoman Empire have been disputed (especially in cases where documentation hasn’t survived). However, unlike some other controversial objects remaining in foreign museums, the Altar’s acquisition has been accepted as legal by the Turkish government.

[1] As of writing, the Pergamon Museum is currently under renovations until 2024. The Altar is not currently on view, but initiatives have been taken to make the altar accessible to the public through a 3D model and temporary exhibition building featuring a panorama of the city in Roman times.

[2] Apollodorus, Library, In Loeb Classical Library, translated by Sir James George Frazer (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1921) 1.6.1-2.

[3] Hesiod, Theogony, translated by M.L. West (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 173–206.

[4] Bernard Andreae, “Dating and Significance of the Telephos frieze in Relation to the Other Dedications of the Attalids of Pergamon,” In Pergamon: The Telephos Frieze from the Great Altar, edited by R. Dreyfus and E. Schraudolph (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 1996-1997), pp. 122–123.

[5] ]For example, the star also adorned Macedonian coinage, such as on a silver tetradrachm struck under Philip V (186/5–183/2 B.C.E.), now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

[6] Emma Aston, Mixanthrôpoi: Animal-human hybrid deities in Greek religion (Liège: Centre International d’Étude de la Religion Grecque Antique, 2011), p. 19. She argues that three themes are often used to address the animal/human relationship: “combat, bestiality, and metamorphosis.”

Cite this page as: Karin E. Christiaens, "The Pergamon Altar," in Smarthistory, April 1, 2021, accessed May 30, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-pergamon-altar/.

A group of statues depicting dying Gauls, the defeated enemies of the Attalids, were situated inside the Altar of Zeus. The original set of statues is believed to have been cast in bronze by the court sculptor Epigonus in 230–220 BCE. Now only marble Roman copies of the figures remain.

Like the figures on the frieze and other Hellenistic sculptures, the figures are depicted with lifelike details and a high level of naturalism. They are also depicted in the common motif of barbarians. The men are nude and wear Celtic torcs . Their hair is shaggy and disheveled. The figures are positioned in dramatic compositions and are shown dying heroically, which turns them into worthy adversaries, increasing the perception of power of the Attalid dynasty. All three figures in the group are depicted in a Hellenistic manner. To fully appreciate the statues, it is best to walk around them. Their pain, nobility, and death are evident from all angles.

One Gaul is depicted lying down, supporting himself over his shield and a discarded trumpet. He furrows his brow as he looks downward at his bleeding chest wound as he prepares himself for death. His muscles are large and strong, signifying his strength as a warrior and implying the strength of the one who struck him down.

Dying Gaul: This is a Roman marble copy of the Greek bronze original by Epigonos, c. 230–220 BCE, in Pergamon, Turkey.

Two other figures complete the group. One figure depicts a Gallic chief committing suicide after he has killed his own wife. Also known as the Ludovisi Gaul, this sculpture group displays another heroic and noble deed of the foes, for typically women and children of the defeated would be murdered to avoid them from being captured and sold as slaves by the victors. The chief holds his fallen wife by the arm as he plunges his sword into his chest, where blood is already exiting the wound.

Ludovisi Gaul: This is a Roman marble copy of the Greek bronze original by Epigonos, c. 230–220 BCE, in Pergamon, Turkey.

Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

The Hellenistic Period is shared under a not declared license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

Pain is visible on the face of this dying warrior. Did the ancient Greeks sympathize with their defeated enemies?

Dying Gaul and the Gaul killing himself and his wife (The Ludovisi Gaul), both 1st or 2nd century C.E. (Roman copies of Third Century B.C.E. Hellenistic bronzes commemorating Pergamon’s victory over the Gauls likely from the Sanctuary of Athena at Pergamon), marble, 93 and 211 cm high (Musei Capitolini and Palazzo Altemps, Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome)

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums); speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The sculptural group known today as the Laocoön or Laocoön and his Sons has been both one of the most influential ancient artworks in the history of art and one of the most fiercely debated. It has been copied by countless artists, and numerous books have been written about it, yet there is still little scholarly consensus about the circumstances of its creation.

The statue was discovered in 1506 on the Esquiline Hill in Rome by a farmer working in his vineyard. The Laocoön was only one of a number of ancient artworks that had been abandoned, forgotten, and eventually buried under later buildings and streets. During the Renaissance, a number of these artworks were rediscovered, either accidentally during construction projects or purposefully by people hunting for the artworks which had become greatly admired. One of the first people to see the statue was Michelangelo, who was sent by the pope, Julius II, along with architect Guiliano da Sangallo, to inspect the statue after its excavation. Julius, like many of his sixteenth-century Italian contemporaries, was a connoisseur and collector of ancient Greek and Roman art. He purchased the statue, and it has remained in the collection of the Vatican ever since.

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Most likely dating to the first century B.C.E. or first century C.E., the statue is made of six blocks of Greek Parian marble. It is over-life sized, at a height of 6’ 8”. The composition depicts the tortuous death of Laocoön and his two sons by snakes (read the full story below). All three are nude with clearly defined, exaggerated musculature. Bands of clenched muscles are visible under the skin of Laocoön’s torso as he reaches up to fight off the snakes. The statue, like all ancient Greek and Roman marble sculptures, would have been painted originally. The bright green of the twisting snakes and the red blood drawn by their bites would have stood out against the tan flesh of Laocoön and his sons.

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Laocoön is at the center of the composition, sitting in a twisted position on an altar. One snake sinks its teeth into his hip. Laocoön throws his head back as he screams in agony. His hair and beard curl in deeply carved locks, contributing to the sculpture’s dramatic tone. Based on surviving paint on his eyes, some scholars have argued that he has been blinded by the bites of the snakes.

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Laocoön is flanked by his two teenaged sons. The figure on the left, the younger of the two, has gone limp, and it is likely that he is already dead. The older son, on the right, pulls snake coils off his leg and arm. He turns to look at his father, an expression of horror and confusion on his face. With its emphasis on theatricality and exaggerated realism, it is similar to artworks of the so-called Hellenistic baroque, such as the Nike of Samothrace and the Great Altar at Pergamon. While the style is most closely associated with the city of Pergamon and the island Rhodes in the second century B.C.E., Hellenistic baroque had an enduring popularity, and artworks in the style continued to be produced into the Roman Imperial period, with Rome becoming a center of Hellenistic art.

The myth of Laocoön dates back to the seventh century B.C.E. It was part of the Epic Cycle, a series of poems that told the story of the Trojan War (Greeks against the city of Troy, in present-day Turkey). Today, only the Iliad and the Odyssey survive, but we have fragments or descriptions of the other volumes. Laocoön appeared in the now-lost Ilioupersis (the sack of Troy) by Arktinos of Miletos. Versions of Laocoön’s story appeared after that, notably in a now-lost fifth century B.C.E. play of Sophocles.

The version closest chronologically to the Laocoön statue appeared in Roman writer Vergil’s Aeneid, published in 19 B.C.E. The Aeneid tells the story of the Trojan warrior Aeneas who escapes from Troy during its destruction and makes his way to Italy, where he rules over the Latin people. The story of Laocoön forms part of book two, which recounts the sack of Troy. The Greeks pretended to give up their siege of Troy with its unbreakable walls, leaving only a large wooden horse as a final offering to the gods. In actuality, some hid out of sight while others hid inside the horse. Only a few Trojans spoke against bringing the horse inside the city. The first was Cassandra, who was blessed with the gift of prophecy, but cursed that no one would ever believe her. The other was Laocoön, a priest of Neptune (Greek Poseidon). He warned the Trojans with his now famous line, “I fear the Greeks, even when they bring gifts.” But the gods had decided the Greeks were to win the war, and no one, divine or mortal, can defy fate. So the gods sent a pair of snakes to silence Laocoön. They came from the sea, attacking Laocoön and his sons while he made a sacrifice. They bit and wrapped themselves around the three, killing first the sons and then Laocoön. This is the moment represented in the marble statue.

Trojan war stories were popular in ancient Rome, especially during the reigns of the Julio-Claudian emperors (27 B.C.E.–68 C.E.). The myths connected the Romans back to the ancient and revered past, giving them legitimacy as a cultural and military power through these connections. The Julian family traced their lineage directly back to the Trojan warrior Aeneas, and so actively promoted art and literature like the Aeneid that focused on Troy.

Scene showing Laocoön, 1st century C.E., atrium of the House of Menandro, Pompeii (Wikimedia CC BY-SA 3.0)

While Laocoön was a recurring subject in texts, he was not as popular in art. Images of Laocoön have been identified on a few pots made by south Italian Greeks in the fourth century B.C.E., but most of the known images are Roman. Gems dating to the late imperial period as well as two first-century C.E. paintings from houses in Pompeii depict the death of Laocoön. Artworks are few, however, and the marble statue is the only monumental depiction of the subject to survive.

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Laocoön is fairly unusual among surviving ancient artworks because it is described in an ancient text, Natural History, by Pliny the Elder. Most of the famous artworks described by ancient authors have been lost and those artworks that have survived are without ancient textual description.

Pliny, a Roman aristocrat and scholar, published the first volumes of The Natural History in 77 C.E. This encyclopedia was intended to record all known knowledge. In his discussion of famous statues, Pliny describes the Laocoön as he saw it in the house of the ancient Roman emperor Titus, and attributes it to the artists Hagesandros, Polydoros, and Athenodoros of Rhodes. Pliny praises the statue as superior to all other artworks. Despite some inconsistencies between the Laocoön statue and Pliny’s description, notably the statue is made of multiple blocks of stone rather than a single block as Pliny says, it is widely accepted that the Laocoön in the Vatican is the statue described by Pliny.

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Another example of a Greek sculpture that was brought back to Rome, then copied. Lysippos, Apoxyomenos (Scraper), Roman copy after a Greek bronze statue from c. 330 B.C.E., 6′ 9″ high (Vatican Museums)

The circumstances surrounding the creation of the Laocoön, including its date, have been long debated by scholars. While one scholar proposed that the statue was actually a Renaissance forgery by Michelangelo, this theory has been widely discredited, and most scholars date the statue between 150 B.C.E. and 70 C.E. Each of these proposals examine why a statue in the Hellenistic Greek style was found in Rome, and the role of Romans as patrons and collectors of Greek sculpture.

The Romans, especially in the late Republic and early Empire, were active connoisseurs of Greek art. As they conquered Greek territories, they imported large numbers of Greek artworks to Italy, removing them from homes, public buildings, and sanctuaries. Romans displayed Greek artworks in their homes and public spaces, many in contexts far removed from their original locations and purposes. These artworks took on new meanings as symbols of the wealth and education of their owners. The Romans also commissioned copies of famous statues as well as new compositions inspired by Greek originals. Rome became a center of Hellenistic art as Greek artists moved to Italy to work for wealthy Romans.

North side of grand staircase, Pergamon Altar (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Theories that posit the earliest date for the Laocoön propose that, based on stylistic similarities, the Laocoön is contemporary to the second-century B.C.E. Great Altar at Pergamon and that it was made in the Greek island of Rhodes before being exported to Rome. Other scholars propose that the marble statue found in Rome was a copy of an earlier second-century Greek original. Most writers, however, argue that the Laocoön was made in Rome for Roman patrons.

Part of the Skylla group, 1st century B.C.E.–1st century C.E., marble, Sperlonga (left photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0; right photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

Support for a Roman context for the creation of the statue comes from the site of Sperlonga, located between Rome and Naples. Here, the emperor Tiberius had a grotto for dining and entertainment decorated with monumental marble statues. The statues are over-life sized and depict scenes from the Trojan war or the life of Odysseus. They are in the same dramatic, hyper-realistic style as the Laocoön, and an artist’s signature was found on the sculptural group that depicted Odysseus’ run-in with the sea monster, Skylla attributing the statues to Hagesandros, Athenadoros, and Polydoros of Rhodes—the same artists to whom Pliny attributes the Laocoön. Debates over the creation of the Laocoön statue are therefore intertwined with the Sperlonga statues.

Most recent scholarly discussions have centered on whether the sculptures were made specifically for the grotto and Titus’s palace or whether they were made earlier and moved to these locations. While there is still no definitive consensus, most scholars now place both the Sperlonga statues and the Laocoön in the first century B.C.E. or first century C.E. Their dramatic, Hellenistic style, along with the focus on Trojan war themes place them in line with the concerns of upper-class Roman patrons in these periods.

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

From Pliny to Michelangelo to modern visitors to the Vatican Museums, the Laocoön statue has made an impact on its viewers. Its dramatic depiction of the agony of Laocoön and his sons forges an emotional connection with its audience. While scholars continue to debate how and when it was created and its ancient context, its legacy is unquestionable.

Cite this page as: Dr. Amanda Herring, "Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons," in Smarthistory, August 25, 2021, accessed May 30, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/athanadoros-hagesandros-and-polydoros-of-rhodes-laocoon-and-his-sons/.

Alexander Mosaic, c. 100 B.C.E., Roman copy of a lost Greek painting, House of the Faun, Pompeii, c. 315 B.C.E., Hellenistic Period (Archaeological Museum, Naples); speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

The Alexander Mosaic as seen on the wall of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, Alexander Mosaic, created in the 2nd century B.C.E., from the House of the Faun in Pompeii

A mighty general (Alexander the Great) charges on horseback across the field of battle. His spear makes contact with a soldier’s torso, who begins to recoil in pain and shock, on the verge of falling over the dead body of a horse strewn on the ground behind him. On the other side of the battlefield, a charioteer scrambles frantically to turn his horses around, trampling bodies beneath their hooves, in an attempt to get the opposing general (Darius) to safety.

These are just some of the evocative scenes depicted in the Alexander Mosaic.

Annotated detail, Alexander Mosaic, created in the 2nd century B.C.E., from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, reconstructed in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

This battle is usually identified as the Battle of Issus, a great fight that occurred on November 5, 333 B.C.E. in what is now modern-day Turkey [1]. It took place between the (Hellenic League) forces of the Macedonian-Greek Alexander the Great and the (Achaemenid Persian) forces of Darius III—a struggle which would ultimately result in a victory for Alexander.

Detail of tesserae, Alexander Mosaic, created in the 2nd century B.C.E., from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, reconstructed in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

The Alexander Mosaic (8 ft 11 in × 16 ft 10 in) is made up of approximately 1.5 million tesserae, which are small, cubed pieces of glass or stones cut into shape. The mostly earth-colored stones are remarkably tiny and used to emphasize the details of the scene. They are laid down in a style known as opus vermiculatum, a technique which is identified as “worm-like” due to the curved lines of tesserae placed to emphasize features and figures within the work.

The mosaic, which was created in the 2nd century B.C.E., once covered the entire floor of a room located between the two peristyle gardens of the large and grand House of the Faun in Pompeii. Today, a modern replica can be seen in Pompeii, while the original has been transferred to the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (Naples National Archaeological Museum). The original mosaic survives in such good condition because it was protected by layers of ash from the 79 C.E. volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius until its rediscovery in 1831.

Modern Reconstruction of the Alexander Mosaic, in situ at the House of the Faun in Pompeii (closer view here)

Though parts of the mosaic have been damaged in the more than two millennia since its creation, much of the dramatic scene is still visible today.

Detail of Alexander the Great, Alexander Mosaic, created in the 2nd century B.C.E., from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, reconstructed in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Near the left side of the mosaic, Alexander charges forward on his horse (named Bucephalus), fully armored, but wearing no helmet. His gaze is intense and confident, and his hair flies out behind him from the force of his forward momentum. His army follows closely as they advance towards the spear-carrying soldiers of the Persian army. In his right hand he holds a sarissa, a type of long spear invented by his father (Philip II, the former King of Macedon), which became an essential tool of Alexander and his forces as they conquered his empire.

Detail of Darius III, Alexander Mosaic, created in the 2nd century B.C.E., from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, reconstructed in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Alexander rides towards the Persian army, led by Darius III, located on the right side of the mosaic, standing atop his chariot.

Detail of an impaled soldier (often identified as one of Darius’ kinsmen), jumping in front of the spear and taking the blow meant for his king (Darius III), Alexander Mosaic, created in the 2nd century B.C.E., from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, reconstructed in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Before Alexander’s spear can make contact with Darius, a man, often identified as one of Darius’ kinsmen, jumps in front of the spear and takes the blow meant for his king. Behind Darius and facing in the opposite direction, the charioteer frantically tries to wheel the chariot around. Holding the reins tightly with his left hand, he raises a whip in his right hand to spur the horses to move faster through the crowd of soldiers across a battlefield that is strewn with blood, bodies, and abandoned weapons. The shock of this moment is reflected in Darius’ face. The artist succeeds in capturing the devastation and fear in Darius’ facial expression. He desperately reaches out in vain towards his dying kinsman, looking towards Alexander.

Detail of Persian soldiers and Darius III in his chariot, Alexander Mosaic, created in the 2nd century B.C.E., from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, reconstructed in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

The artist captures the frenzied movements and fearful eyes of the horses as they trample soldiers and Darius flees from the battle, eyes still fixed on Alexander.

Although Alexander wins this battle, Darius is the tallest figure in the mosaic, elevated by the chariot on which he stands and puts his grief on prominent display.

This mosaic is remarkable not just for representing this significant battle, but also for the level of detail and naturalism it displays. All of the figures from humans to horses are rendered with a sense of three-dimensional, naturalistic modeling. By the late classical period and into the Hellenistic period, representations of figures had shifted from classical idealism to humanistic depictions which emphasized realistic anatomy and emotion, as is evident here.

Detail of soldier’s face with tesserae arranged to create light and shadow, Alexander Mosaic, created in the 2nd century B.C.E., from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, reconstructed in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

The tesserae are also used effectively to create light, shadow, and reflection. For example, there is a figure who has been knocked to the ground by the fleeing chariot. In a moment of introspection, he stares at the reflection of his own face on a shield, perhaps just before the moment of his own death. The incredible skill of the artist renders dynamic moments like these in realistic ways.

Detail of fallen soldier’s face reflected in a shield, Alexander Mosaic, created in the 2nd century B.C.E., from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, reconstructed in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Though the landscape in which the battle takes place is a barren one with little suggestion of setting, the figures display three-dimensionality, an excellent example of how well the ancient Greeks understood the body and how it moved through space. This is evident, for example, in the foreshortening of figures like the horse near the center right of the mosaic. The horse’s flank also displays tonal gradation, where colors transition gradually from a lighter tone to a darker one.

Detail of foreshortened horse, Alexander Mosaic, created in the 2nd century B.C.E., from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, reconstructed in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Compared to the crowded and frenetic battle scene below, the top half of the composition is mostly empty, broken only by spears and a bare, gnarled tree.

So why is the top half of this mosaic so vacant? The answer likely lies in the mosaic’s origins.

This stunningly detailed floor mosaic is usually believed to be a copy of an earlier Greek wall painting. Ancient Greek paintings were a highly popular and respected art form, but unfortunately, examples today are nearly nonexistent. [2] Unlike Roman wall paintings which were painted directly on the wall and therefore fixed and immovable, Greek wall paintings were usually painted on panels which were inserted into walls. These panel paintings could be removed from the wall and replaced as desired. While this was very practical at the time, they were constructed from more impermanent materials which frequently do not survive.

As a painting, the scene would have been displayed on a vertical wall. Given the size, much of the top half of the composition would have been well above the heads of the viewers and therefore not as easily viewed or necessary to fill with objects and figures. We can get a sense of what this looks like today from the mosaic’s wall-mounted position in the Naples National Archaeological Museum.

Though the Greek paintings themselves no longer exist, their influence can be seen in Etruscan and Roman paintings and mosaics, such as this one. Alexander the Great employed many artists during his reign as did his father before him. As Alexander’s empire spread, so too did the artistic styles that began to develop during his lifetime. Even after his death, artists during the Hellenistic period copied or were influenced by these works.

This was a mosaic meant to impress. The House of the Faun is the single largest residence in Pompeii and one of the most opulently decorated. By choosing to showcase this scene in his house, which is a copy of such a famous work, it would suggest to guests that the owner was highly educated in Greek culture and speaks to the Roman fascination with Greek art.

Although he was outnumbered by Darius’ forces, Alexander defeated him at the Battle of Issus. The battle was considered a turning point leading to the decline of Achaemenid power, and ultimately, paved the way for Alexander’s conquest, which culminated in him burning the Persian capital Persepolis in 330 B.C.E. Even though he died at the young age of 32, Alexander succeeded in creating one of the largest empires of the ancient world.

Although none of the original paintings of Alexander and Darius survive, the mosaic allows us to see what it may have looked like, capturing a moment in time during a frenetic and emotional battle. Even after more than 2,000 years, the mosaic continues to fascinate all those who look upon it.

Alexander Mosaic, created in the 2nd century B.C.E., from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, reconstructed in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Notes:

[1] The other possible candidate is the Battle of Gaugamela which took place in 331 B.C.E. and is the second time that Alexander and Darius directly fought each other.

[2] A few mid – late 4th century B.C.E. Macedonian paintings survive in the tombs of Vergina, Greece.

Cite this page as: Jessica Mingoia, "Alexander Mosaic from the House of the Faun, Pompeii," in Smarthistory, June 6, 2021, accessed May 30, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/alexander-mosaic-from-the-house-of-the-faun-pompeii/.

Nike (Winged Victory) of Samothrace, Lartos marble (ship) and Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E. 3.28 m high, Hellenistic Period (Musée du Louvre, Paris); a conversation between Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Standing at the top of a staircase in the Musée du Louvre in Paris, the Nike of Samothrace looks down over her admiring crowds. One of the most revered artworks of Hellenistic Greek art, the Nike has been on display in the Louvre since 1866. The statue was brought to France by Charles Champoiseau, who found it in pieces during excavations on the island of Samothrace in 1863. Champoiseau was serving as vice-consul in the Ottoman city of Adrianople (modern Edirne, in Turkey), and visited Samothrace specifically to look for antiquities. At the time, European travelers and archaeologists, as well as many amateurs like Champoiseau, conducted excavations and combed ancient sites in the eastern Mediterranean in search of ancient objects to display in their homes and museums. The ownership of ancient objects highlighted appreciation for and connection to the antique past and was understood as a as sign of elite status.

Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The sculptural group consists of two parts, a large ship’s bow made of grey marble and a free-standing white marble statue with the overall composition rising more than eighteen feet (Nike alone is nine feet tall). The flying personification of victory (nikē in Greek means victory) alights on top of the ship, announcing a naval triumph. Her wings stretch dramatically behind her. A forceful wind blows her drapery across her body, gathering it in heavy folds between her legs, around her waist, and streaming behind her, conveying a vivid illusion of movement. Thin and gauzy across her breasts, abdomen, and legs, this same drapery reveals her body underneath the clothing, creating an erotized vision of the female form.

Similar to other Hellenistic artworks such as the Laocöon and the Great Altar at Pergamon, the Nike is extraordinarily dramatic in composition and style. It is intended to be viewed from multiple angles, encouraging the viewer to move around the statue, and through this interaction engage with the artwork physically and emotionally.

Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Right hand , Nike of Samothrace, c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: 林高志, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The statue, as it stands today in the Louvre, has been partially restored. While it is now plain white marble, the statue, like all ancient Greek and Roman marble sculptures, would have originally been brightly painted, and traces of pigment have been found on the statue. The right wing is a modern replica. Surviving fragments indicate that the right wing would have risen higher than the left wing and slanted upward. The missing feet, arms, and head have not been restored, giving the statue its now iconic form.

Nike’s surviving right hand (which was found in 1950) gives a clue to her original appearance. Her fingers are outstretched, indicating that she may have been making a gesture of greeting.

Nike, c. 200–150 B.C.E., terracotta, from Myrina, Anatolia (The British Museum; photo: Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A series of small terracotta figurines of Nike, made in Myrina in Anatolia, give further insight into the original appearance of the Nike of Samothrace. These statues show the goddess in flight, her drapery blown by the wind, with her wings stretched behind her balanced by her extended arms in front. Nike of Samothrace most likely appeared similarly, but on a much larger scale.

Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Nike’s wings are a mastery of marble construction. Marble is a heavy material, and compositions that included large protruding, unsupported, large elements such as the wings were rarely seen in earlier Greek sculpture. The now-unknown artist(s) of the Nike of Samothrace solved this problem by creating slots on Nike’s back into which the wings were inserted, and designing the wings with a downward slope so that the weight of the wings rested primarily against the body and did not need an external support.

Nike of Paionios, c. 420 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Nike on a Terracotta lekythos, c. 490 B.C.E., attributed to the Dutuit Painter (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Nike was both the goddess of victory and the personification of victory itself, in both war and athletic competitions. She was rarely featured in Greek myth and had no easily definable personality or biography. She was usually worshipped alongside other gods or as an attribute of another deity, such as Athena Nike (Athena Bringer of Victory) on the Athenian Acropolis. Yet, she was regularly featured in Greek art, appearing on pots, architectural sculpture, and free-standing sculptural compositions, either singly or in multiple.

Her iconography is distinctive—a winged, youthful woman—and she is one of the most easily identifiable Greek mythological figures. She crowns gods and victorious athletes with leafy circlets or holds palm fronds symbolizing victory. She was the perfect subject to commemorate military triumphs and was regularly featured in victory monuments, notably the fifth-century Nike of Paionios, erected at the Sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia to celebrate a Peloponnesian War victory.

The Nike of Samothrace was originally erected as a military victory monument in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods (Theoi Megaloi) on Samothrace, a small island in the northern Aegean Sea. While the permanent population of the island was relatively small, an influx of worshippers regularly descended upon Samothrace to participate in religious rites hosted by the sanctuary, especially in the Hellenistic and Roman periods when the sanctuary was at its height of popularity. The cult of the Great Gods was a mystery religion, meaning that worshippers needed to be initiated into the cult before they were allowed to participate, and the rites were kept secret from everyone except the initiates. Since secrecy was so central to the cult, modern scholars do not know exactly what was involved in the rituals. However, we do know that the cult promised its initiates safety at sea and personal moral benefit.

Plan of the sanctuary of the Great Gods, Samothrace, with the location of Nike of Samothrace at location 9

Worshippers came from throughout the ancient Mediterranean to worship, and initiation was open to all, regardless of social class, gender, or citizenship. Royals, elites, commoners, and enslaved people were all initiated into the cult. The Roman writer Plutarch even says that the parents of Alexander the Great, Philip and Olympias, met while they were initiates on Samothrace.

The sanctuary was located in a narrow valley, with buildings located on the valley floor and on terraces cut into the hillsides. The Nike monument was on the west slope, in a niche at the top of the hill behind the theater. Placed at one of the highest points in the sanctuary, it would have been visible from numerous viewpoints as initiates moved through rituals.

Scholars once believed the Nike of Samothrace stood in a fountain. Archaeological evidence for this theory has now been shown to post-date the monument, and while there is still debate about whether the structure was roofed or enclosed by walls, scholars today hold that the Nike group was housed in a small building, open on the north side, with the Nike facing out over the theater. The illusion of her blowing drapery would have been reinforced by the actual onshore wind that would have blown across the valley.

Due to the popularity of the cult, and its connection to protection at sea, it makes sense that a military leader would have dedicated a monument commemorating a naval victory at Samothrace. The triumphant commander would have proclaimed his victory before an international audience, including perhaps those he defeated. The dedicatory inscription, which most votive statues in Greek sanctuaries included, has not survived, so it is unknown who dedicated the statue or what victory it commemorated.

Left: Athena panel, east frieze, Pergamon Altar, c. 197-139 B.C.E. (Staatliche Museen, Berlin); right: Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Based on stylistic similarities between the Nike of Samothrace and the external frieze of the Great Altar at Pergamon, notably its theatricality and hyperrealism, the statue is usually dated to the first half of the second century B.C.E. In the period, naval battles between the Hellenistic kingdoms were common as they fought for military, political, and economic control. The Greek Hellenistic world stretched from mainland Greece through Egypt, across Anatolia and the Near East to central Asia. The territory was divided into a series of empires. While most were hereditary monarchies, rulership was frequently unstable; power regularly changed hands and borders shifted. Many of these shifts in power were determined through warfare, and a strong military was a key part of a leader’s ability to hold onto his throne. The Hellenistic dynasts carefully built up their armies and navies, attempting to outdo one another both in the size of their forces and the advancement of their military technology. Triumphs were widely advertised, and victory monuments were an important part of royal propaganda. Erected both at home and at sites like Samothrace, they ensured that the nation’s subjects, allies, and enemies knew of an empire’s military might.

Nike of Samothrace (winged Victory), Lartos marble (ship), Parian marble (figure), c. 190 B.C.E., 3.28 meters high (Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0))

Scholars have proposed a number of possible battles that the Nike of Samothrace commemorated, but most theories argue that the statue commemorated a victory over the island of Rhodes. This is based in part on the material of the ship on which Nike stood, a grey marble from the Lartos quarries on Rhodes. The Nike herself is made of a white Parian marble, which was revered as a superior material for sculpture, and exported throughout the Mediterranean. Lartian marble was much less commonly used, and we see it primarily in monuments on Rhodes or commissioned by Rhodians. In addition, the amount of marble used in the Nike of Samothrace was large, weighing around 30 tons, and would have been a full shipload on a typical merchant ship. Given the cost to ship the marble from Rhodes, it was likely specially ordered and intended to make a statement, connecting it to the Rhodians.

Tetradrachm (coin) showing Nike blowing a trumped, 301–295 B.C.E., minted by Demetrius Poliorcetes, silver (Münzkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin)

The form of a naval victory monument featuring a carved marble ship appears to be a popular type in the Hellenistic period, and parallels for the Nike of Samothrace are widespread—they have been found in mainland Greece, the Aegean islands, and Cyrene in Libya. The closest parallel appeared on coins minted by Demetrius Poliorcetes of Macedonia at the end of the third century B.C.E. The coins depict Nike on the prow of a ship, blowing a horn to announce a victory.

The Nike of Samothrace, while originally located in a sanctuary on a small island in the north Aegean, was intrinsically part of a Hellenistic world defined by the transmission of ideas, goods, people, and artistic motifs over large distances. Today, it is admired by an international audience in the Louvre, and its original intention was similar. The Sanctuary of the Great Gods, promising protection at sea to its initiates, was visited by worshippers from across the Mediterranean. The statue commemorated a naval triumph, and its placement in this location afforded it a broad audience, advertising its dedicator’s military prowess to the world. The Nike’s windswept drapery, outstretched wings, and dramatic location assured that it would have drawn the eyes of everyone who saw it.

Cite this page as: Dr. Amanda Herring, "Nike (Winged Victory) of Samothrace," in Smarthistory, August 11, 2021, accessed May 30, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/nike-winged-victory-of-samothrace/.