Introduction to Carolingian Art

Map of Europe at the time of Charlemagne

Charlemagne, King of the Franks and later Holy Roman Emperor, instigated a cultural revival known as the Carolingian Renaissance. This revival used Constantine’s Christian empire as its model, which flourished between 306 and 337. Constantine was the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity and left behind an impressive legacy of military strength and artistic patronage.

Charlemagne saw himself as the new Constantine and instigated this revival by writing his Admonitio generalis (789) and Epistola de litteris colendis (c.794–797). In the Admonitio generalis, Charlemagne legislates church reform, which he believes will make his subjects more moral and in the Epistola de litteris colendis, a letter to Abbot Baugulf of Fulda, he outlines his intentions for cultural reform. Most importantly, he invited the greatest scholars from all over Europe to come to court and give advice for his renewal of politics, church, art and literature.

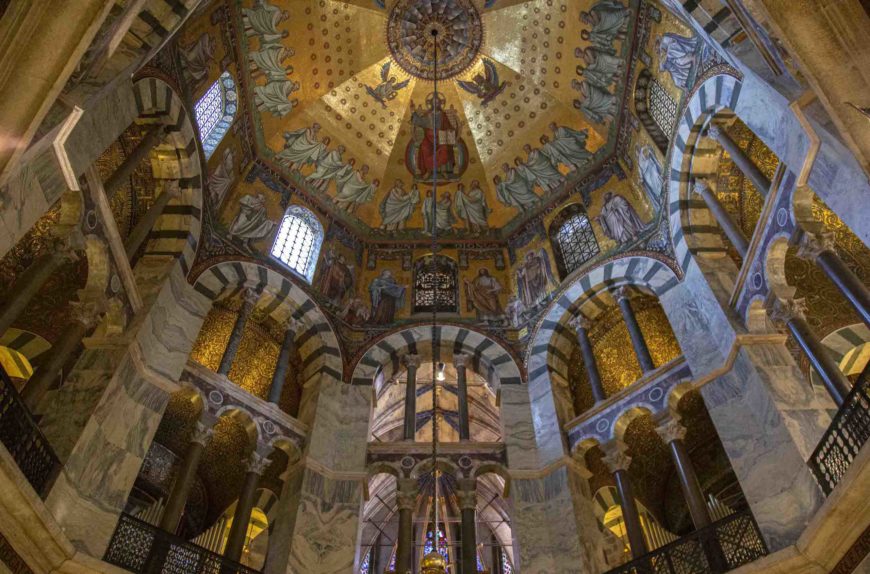

Odo of Metz, Palatine Chapel Interior, Aachen, 805 (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Carolingian art survives in manuscripts, sculpture, architecture and other religious artifacts produced during the period 780–900. These artists worked exclusively for the emperor, members of his court, and the bishops and abbots associated with the court. Geographically, the revival extended through present-day France, Switzerland, Germany and Austria.

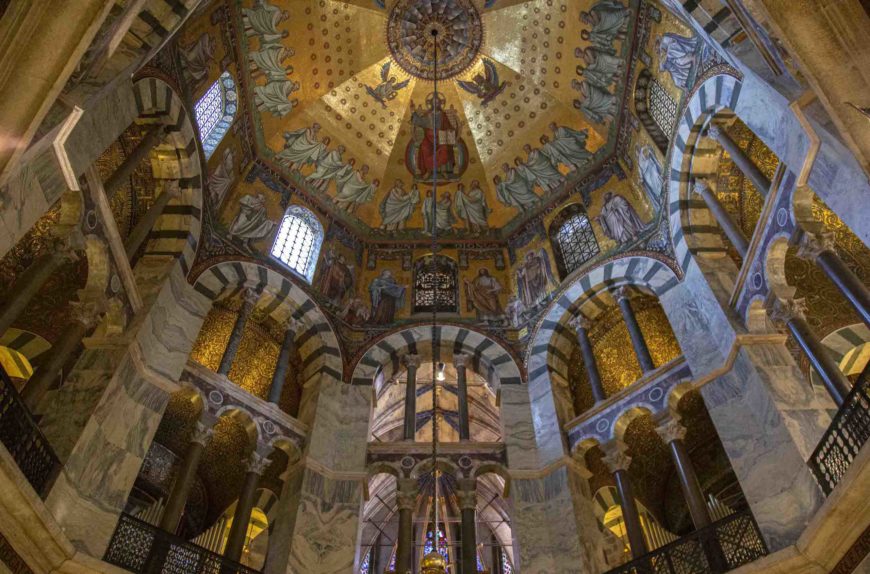

Charlemagne commissioned the architect Odo of Metz to construct a palace and chapel in Aachen, Germany. The chapel was consecrated in 805 and is known as the Palatine Chapel. This space served as the seat of Charlemagne’s power and still houses his throne today.

The Palatine Chapel is octagonal with a dome, recalling the shape of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy (completed in 548), but was built with barrel and groin vaults, which are distinctively late Roman methods of construction. The chapel is perhaps the best surviving example of Carolingian architecture and probably influenced the design of later European palace chapels.

Charlemagne had his own scriptorium, or center for copying and illuminating manuscripts, at Aachen. Under the direction of Alcuin of York, this scriptorium produced a new script known as Carolingian miniscule. Prior to this development, writing styles or scripts in Europe were localized and difficult to read. A book written in one part of Europe could not be easily read in another, even when the scribe and reader were both fluent in Latin. Knowledge of Carolingian miniscule spread from Aachen was universally adopted, allowing for clearer written communication within Charlemagne’s empire. Carolingian miniscule was the most widely used script in Europe for about 400 years.

Figurative art from this period is easy to recognize. Unlike the flat, two-dimensional work of Early Christian and Early Byzantine artists, Carolingian artists sought to restore the third dimension. They used classical drawings as their models and tried to create more convincing illusions of space.

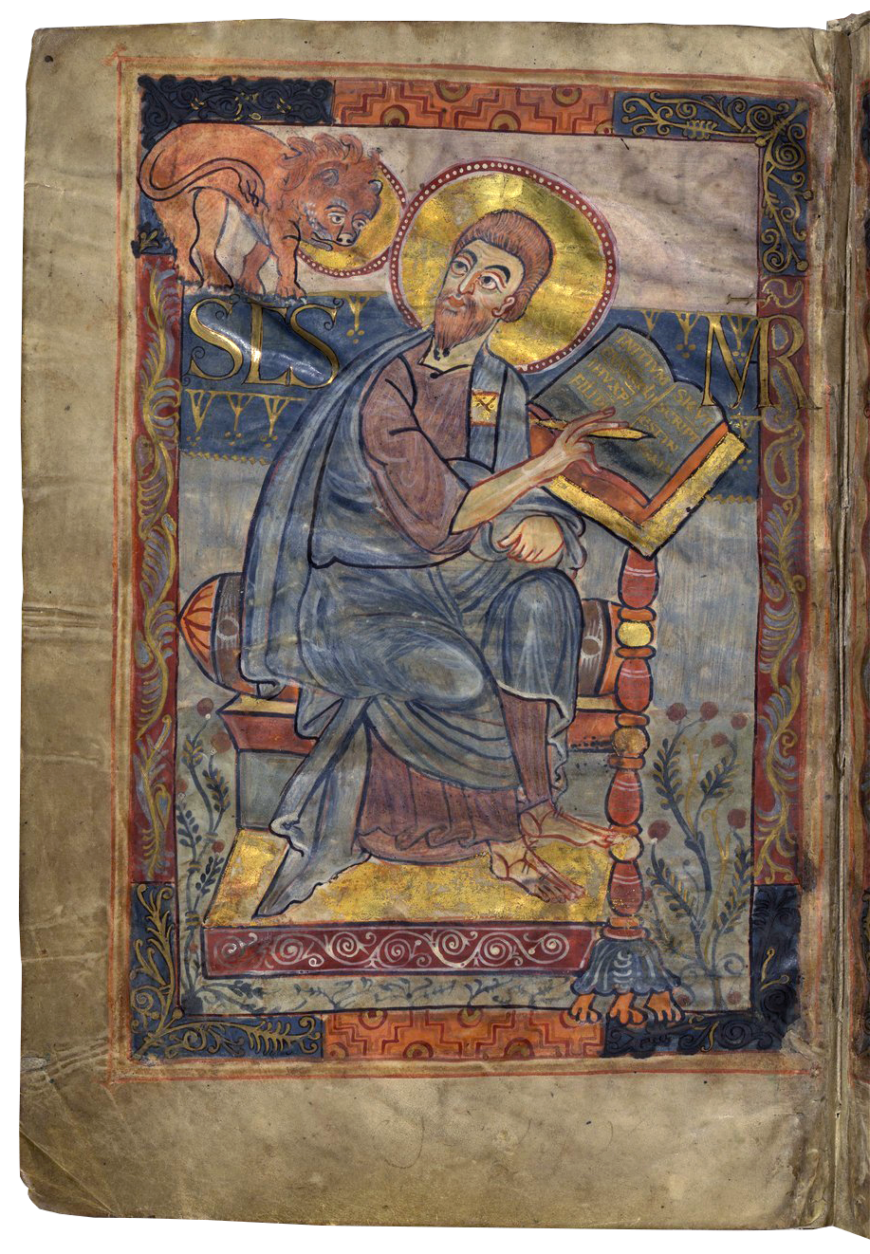

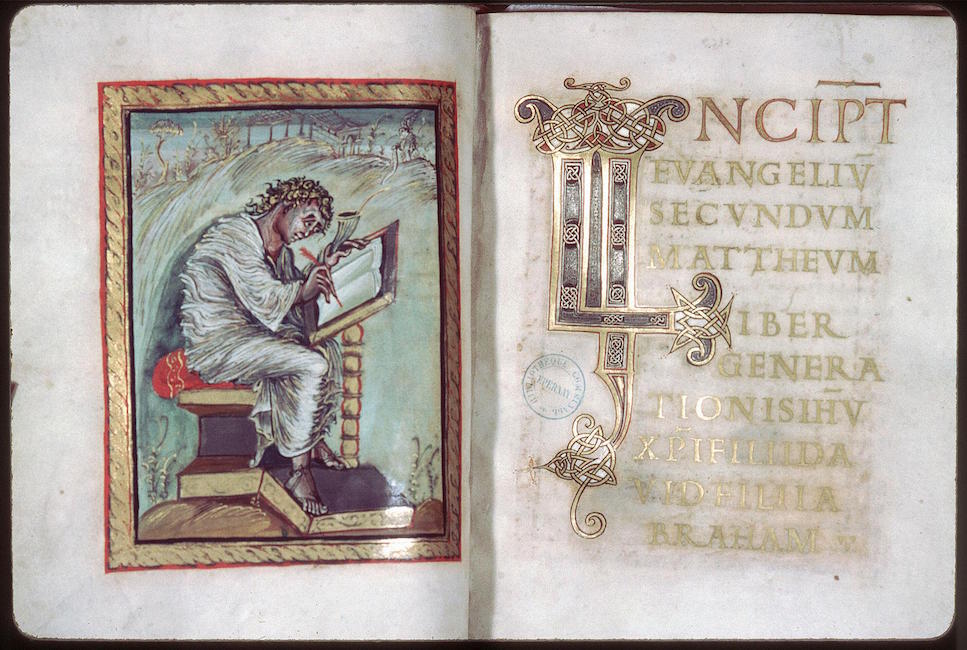

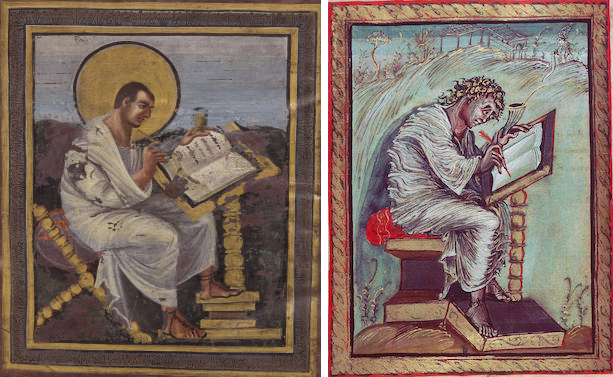

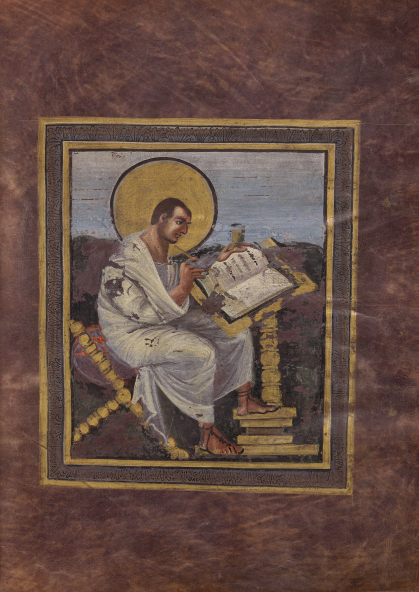

This development is evident in tracing author portraits in illuminated manuscripts. The Godescalc Gospel Lectionary, commissioned by Charlemagne and his wife Hildegard, was made circa 781–83 during his reign as King of the Franks and before the beginning of the Carolingian Renaissance. In the portrait of St. Mark, the artist employs typical Early Byzantine artistic conventions. The face is heavily modeled in brown, the drapery folds fall in stylized patterns and there is little or no shading. The seated position of the evangelist would be difficult to reproduce in real life, as there are spatial inconsistencies. The left leg is shown in profile and the other leg is show straight on. This author portrait is typical of its time.

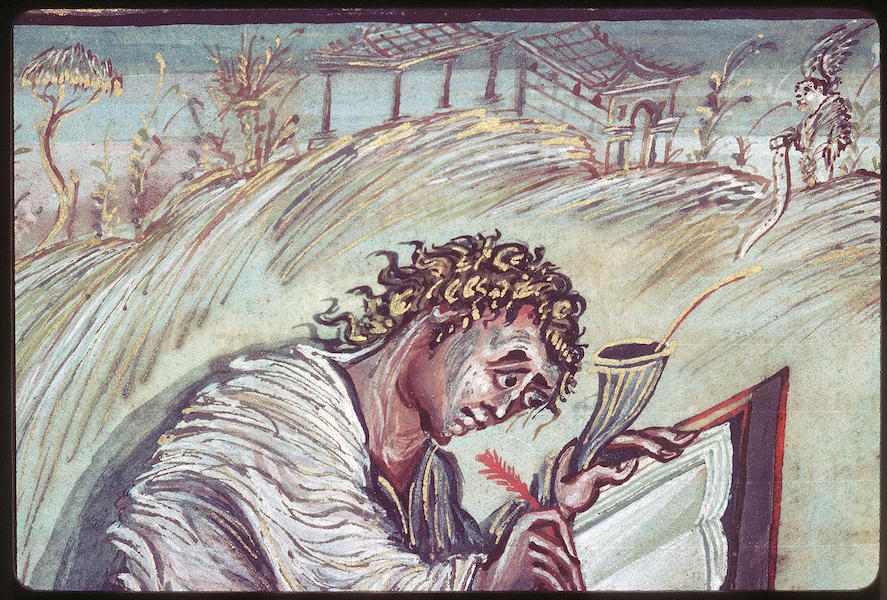

The Ebbo Gospels were made c. 816–35 in the Benedictine Abbey of Hautvillers for Ebbo, Archbishop of Rheims. The author portrait of St. Mark is characteristic of Carolingian art and the Carolingian Renaissance. The artist used distinctive frenzied lines to create the illusion of the evangelist’s body shape and position. The footstool sits at an awkward unrealistic angle, but there are numerous attempts by the artist to show the body as a three-dimensional object in space. The right leg is tucked under the chair and the artist tries to show his viewer, through the use of curved lines and shading, that the leg has form. There is shading and consistency of perspective. The evangelist sitting on the chair strikes a believable pose.

Charlemagne, like Constantine before him, left behind an almost mythic legacy. The Carolingian Renaissance marked the last great effort to revive classical culture before the Late Middle Ages. Charlemagne’s empire was led by his successors until the late ninth century. In early tenth century, the Ottonians rose to power and espoused different artistic ideals.

Cite this page as: Dr. Nancy Ross, “Carolingian art, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, July 6, 2018, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/carolingian-art-an-introduction/.

Charlemagne

A brief overview of Charlemagne and his coronation in 800.

Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Charlemagne (part 1 of 2): An introduction,” in Smarthistory, July 5, 2018, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/charlemagne-part-1-of-2/.

A brief introduction to Charlemagne’s military campaigns and the cultural revival that he supported.

Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Charlemagne (part 2 of 2): The Carolingian revival,” in Smarthistory, July 4, 2018, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/charlemagne-part-2-of-2/.

Palatine Chapel

The octagonal plan references earlier churches and symbolizes regeneration. Was Charlemagne’s throne at its center?

Palatine Chapel (Aix-la-Chapelle), Aachen, begun c. 792, consecrated 805 (thought to have been designed by Odo of Metz), significant changes to the architectural fabric 14–17th centuries (Gothic apse, c. 1355; dome rebuilt and raised in the 17th century, etc.), mosaics and revetment from the 19th century, columns looted by French troops in the 18th century though many were later returned, added back without knowledge as to their original locations in the 19th century. The structure was heavily damaged by allied bombing during WWII and significantly restored again in the second half of the twentieth century. With special thanks to Dr. Jenny H. Shaffer. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Carolingian art and the classical revival

The Palatine Chapel at Aachen is the most well-known and best-preserved Carolingian building. It is also an excellent example of the classical revival style that characterized the architecture of Charlemagne’s reign. The exact dates of the chapel’s construction are unclear, but we do know that this palace chapel was dedicated to Christ and the Virgin Mary by Pope Leo III in a ceremony in 805, five years after Leo promoted Charlemagne from king to Holy Roman Emperor. The dedication took place about twenty years after Charlemagne moved the capital of the Frankish kingdom from Ravenna, in what is now Italy, to Aachen, in what is now Germany.

Map with present-day nations (underlying map © Google)

In the construction of his chapel, Charlemagne made several strategic choices that linked his building to the legacies of ancient Rome and the fourth-century emperor Constantine. The Emperor Constantine was important because he was the first Christian emperor of Rome. The location for the new building was selected because it was an historic Roman site with hot springs that were used for bathing. The materials used for the chapel also invoked Rome; among them were columns and marble stones that Pope Hadrian permitted Charlemagne to transfer from Rome and Ravenna to Aachen around the year 798. A relic of the cloak of St. Martin was installed in the church at its consecration—the choice of a fourth-century Roman soldier who had a vision of Jesus after sharing his cloak with a beggar was another way to reinforce the link of Charlemagne’s rule with Rome.

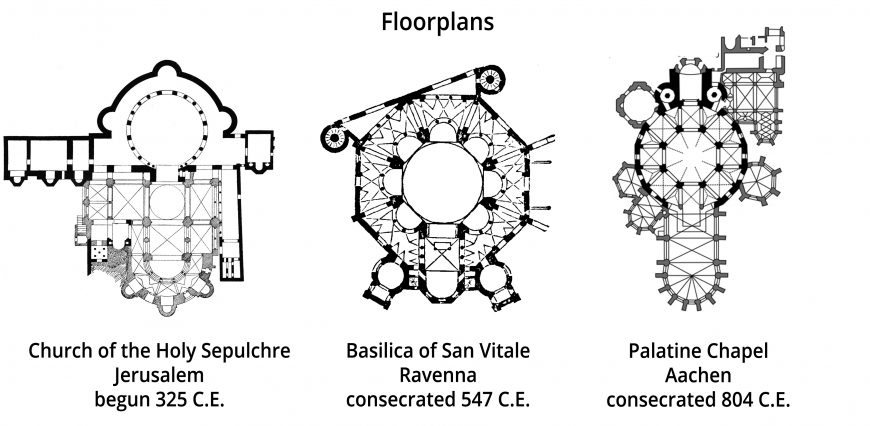

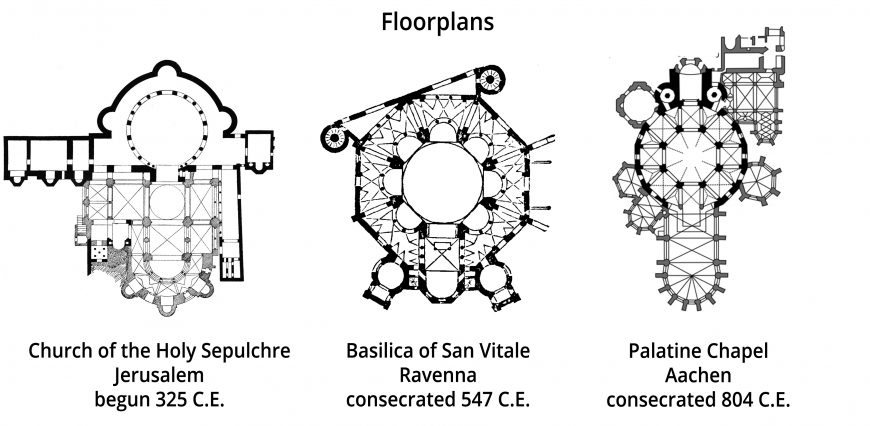

Floorplans of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem; Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna; and Palatine Chapel, Aachen

Two important models (the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and San Vitale in Ravenna)

The chapel’s classical style also referenced its Roman imperial lineage, particularly in its imitation of two significant Christian buildings: the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and San Vitale in Ravenna. The Holy Sepulchre’s building program was started in 325 C.E. by Constantine’s mother, Saint Helena, and completed in 335. The centralized plan and surrounding ambulatory and upper gallery is echoed in the plan of the Palatine Chapel. However, the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem is composed of two main buildings—in addition to the rotunda that covers the tomb is a similar structure over the traditionally-accepted location of the crucifixion. The Holy Sepulchre may also have been the inspiration for the lion-head knockers of the chapel’s bronze doors (below).

Door (detail), Palatine Chapel, Aachen (photo: Bojin, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Because it didn’t receive extensive additions like the Holy Sepulchre, the San Vitale Chapel at Ravenna is probably the best comparison for what the Palatine Chapel would have looked like before its Gothic renovations. San Vitale is a small octagonal church, with a centralized plan and a two-story ambulatory (below).

San Vitale, Ravenna, begun in 526 under Ostrogothic rule, consecrated in 547, completed 548

The octagonal plan of the Palatine Chapel (see plans above) not only recalled that of its two most significant models, but also participated in the tradition of early Christian mausoleums and baptisteries, where the eight sides were understood to be symbolic of regeneration—referencing Christ’s resurrection eight days after Palm Sunday. Its original dome was also based on classical models and bore an apocalyptic mosaic program, consisting of the agnus dei, or Lamb of God (which is, symbolically, Jesus Christ), surrounded by the tetramorph (symbols of the four Gospel writers) and the twenty-four elders described in Revelation 4:4. The agnus dei image was later obstructed by the installation of a chandelier.

Palatine Chapel interior (photo: Velvet, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The octagonal centralized plan of the Palatine Chapel is unique among Carolingian chapels; this may have been because, unlike a longitudinal plan which created a sense of processional direction toward the apse and altar, a centralized plan did not place special emphasis on the altar (and therefore may not have been as effective liturgically for the purpose of a chapel). That said, it does seem to have established an association of Charlemagne with Christ; some scholars believe that Charlemagne’s marble throne (below) was originally located in the center of the octagon on the first floor, that is, directly below the image of the agnus dei, thereby creating a kind of visual link between the emperor and the Christ.

Charlemagne’s throne, Palatine Chapel, Aachen (photo: Berthold Werner, CC BY-SA 3.0)

By presenting his capital at Aachen as a new Rome and himself as a new Constantine through the careful appropriation of late antique artwork and architecture, Charlemagne was not simply making a positive assertion about himself as ruler; he was also implicitly contrasting his reign with that of the Eastern Empire (the Byzantines), a negative stance that was also expressed around the same time in the Opus Caroli Regis contra Synodum (i.e., “The Work of King Charles against the Synod), a detailed response to the Second Council of Nicaea, written on his behalf by Theodulf of Orléans.

Europe before 774 (underlying map © Google)

Palatine Chapel exterior, Aachen, consecrated 805, Carolingian structure visible (lower two stories) (photo: CaS2000, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Charlemagne’s body was interred in the Palatine Chapel after his death in 814. The building would continue to be used for coronation ceremonies for another 700 years—well into the sixteenth century.

Major additions to the chapel began in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, significantly changing the building’s profile and footprint with exterior chapels. After several fires in the seventeenth century, the dome was rebuilt and heightened.

Cite this page as: Dr. Jennifer Awes Freeman, “Palatine Chapel, Aachen,” in Smarthistory, June 11, 2023, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/palatine-chapel-aachen/.

Matthew in the Coronation Gospels and Ebbo Gospels

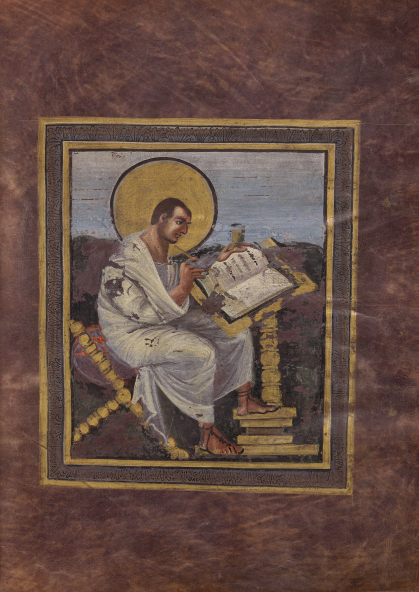

Saint Matthew, folio 15 recto of the Coronation Gospels (Gospel Book of Charlemagne), from Aachen, Germany, c. 800-810, ink and tempera on vellum (Kaiserliche Schatzkammer, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

According to legend, the Vienna Coronation Gospels (c. 795) were discovered in Charlemagne’s tomb within the Palatine Chapel in the year 1000 by Otto III; the emperor had apparently been buried enthroned, that is, sitting up, with the Gospels in his lap. A gospel book is a book containing the books of the four evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, who each offer their story of Christ’s life and death.

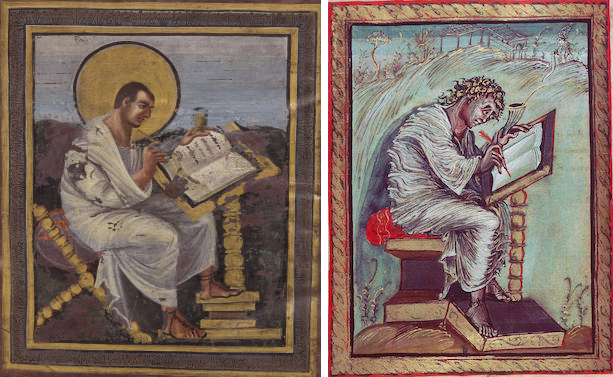

The manuscript is clearly a luxury object, written in gold ink on purple-dyed vellum. Characteristic of the Carolingian Renaissance, the artists of the Coronation Gospels were interested in the revival of classical styles, which effectively linked Charlemagne’s rule to that of the 4th century ancient Roman emperor Constantine. The classical style is evident in the poses and clothing of the four evangelists, or Gospel writers, who recall images of ancient Roman philosophers (for example, this one from The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Charlemagne probably had this Gospel book made before he was crowned emperor. It is such an impressive book that it was used in imperial coronation services from about the twelfth to the sixteenth century.

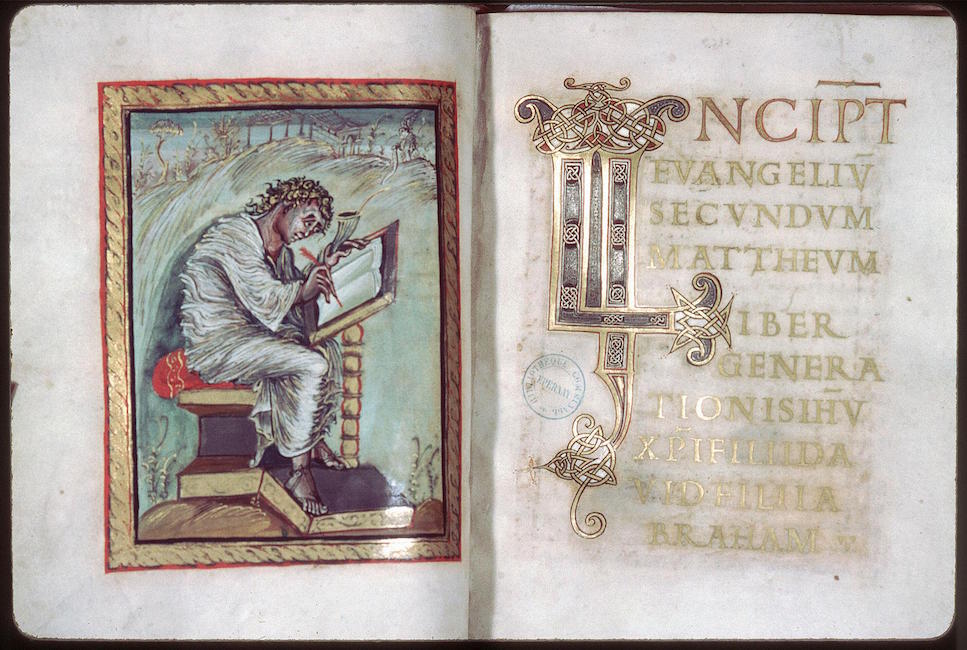

Following the creation of the Coronation Gospels, the Ebbo Gospels (c. 816-35) are most famous for their distinctive style in contrast to contemporary Carolingian illuminated manuscripts. The Ebbo Gospels were made for Ebbo the Archbishop of Rheims, which was one of the major sites for manuscript production at the time.

Saint Matthew, folio 18 verso of the Ebbo Gospels (Gospel Book of the Archbishop of Reims) from Hautvillers, France, c. 816-35, ink and tempera on vellum, 10 1/4 x 8 1/4 (Bibliothèque Municipale, Épernay)

While the author portraits in the Ebbo Gospels (images of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) are consistent with the elements of classical revival (e.g., modeling of figures to make them appear three-dimensional, gradation of the sky, the architecture and furnishings), the style in which the images of the Ebbo Gospels are executed is a notable departure. The brushwork of the author portraits can be described as energetic, expressionistic, even frenzied. The artist remains attentive to the use of highlighting and shadow to create three-dimensional forms, but does so with textured rather than smooth modeling, which creates an effect of movement.

Left: Saint Matthew from the Coronation Gospels (Gospel Book of Charlemagne), c. 800-810, ink and tempera on vellum (Kaiserliche Schatzkammer, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna); right: Saint Matthew from the Ebbo Gospels (Gospel Book of the Archbishop of Reims), c. 816-35, ink and tempera on vellum (Bibliothèque Municipale, Épernay)

This energy is conveyed not only in the brushwork, but also in the composition itself. In the Ebbo Gospels, Matthew is hunched over as if frantically writing on his (still blank) codex, while Matthew’s posture in the Coronation Gospels is more upright and relaxed; his pen grazes his chin, as if he is pausing in thought.

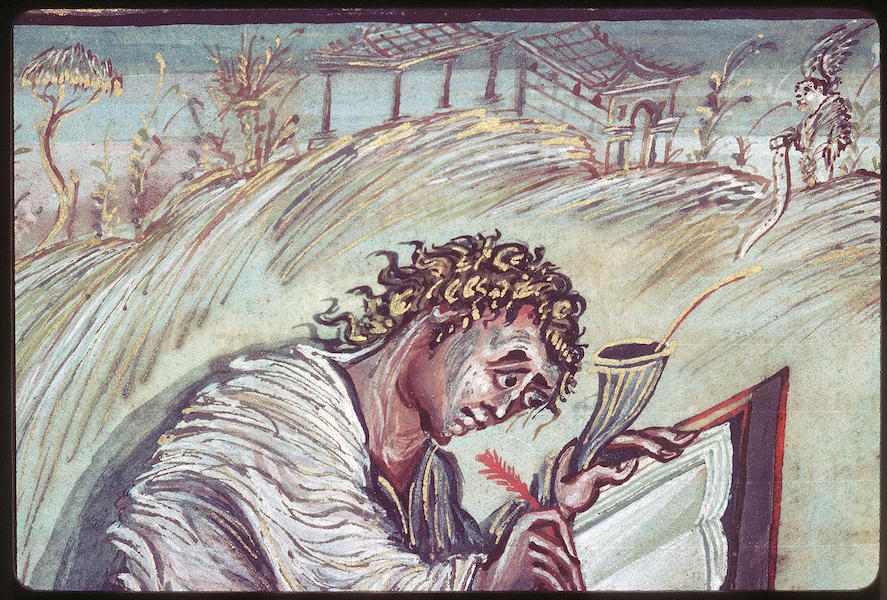

The furniture of the two portraits is very similar in appearance—though the seat in the Coronation Gospels seems to be a folding chair, while that of the Ebbo is a more-sturdy stool. However, the posture of the Coronation Matthew is stable in contrast to that of Ebbo. For example, his right foot rests on the frame of the miniature and his left is flat on the base of his book stand. This miniature is composed of several 45- and 90-degree angles that create a sense of stability and balance. In contrast, the lines in the Ebbo Gospels’ Matthew are dynamic and lack the same sense of equilibrium. For instance, Matthew’s right foot in particular is positioned on the steep, almost vertical, angle of his footrest. Furthermore the book stand is tipped at such a drastic angle that it seems his book will slide right into the viewer’s lap. The energy is also expressed in Matthew’s face, which is drawn up in a furrowed brow. While the Coronation Matthew seems to take a peaceful moment of reflection, the Ebbo Matthew appears to be in anguish over his writing (image below), which is directed by his evangelist symbol, the winged man, who instructs him from the upper right hand corner of the image.

Detail, Saint Matthew, folio 18 verso of the Ebbo Gospels (Gospel Book of the Archbishop of Reims) from Hautvillers, France, c. 816-35, ink and tempera on vellum, 10 1/4 x 8 1/4 (Bibliothèque Municipale, Épernay)

Lastly, it should be noted that the Ebbo Gospels bear some similarities to the infamous Utrecht Psalter (below), which was also made in Rheims at the Benedictine abbey of Hautvillers around the same time (a psalter is a volume containing the Biblical Book of Psalms, often with other devotional material bound in). The images of the Utrecht Psalter are unpainted drawings in brown ink, which are also clearly meant to invoke the style of Late Antiquity. While the sketchy character of the Utrecht Psalter is not quite as dramatic as that of the Ebbo Gospels, the similarity in style can be seen especially in the classical architecture and the rendering of the winged man at the top of the evangelist’s portrait.

Psalm 44, detail of folio 25 recto of the Utrecht Psalter, from Hautviller (near Reims), France, c. 820-835 (University Library, Utrecht)

Cite this page as: Dr. Jennifer Awes Freeman, “Matthew in the Coronation Gospels and Ebbo Gospels,” in Smarthistory, September 15, 2016, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/coronation-gospels/.

Saint Matthew, folio 18 verso of the Ebbo Gospels (Gospel Book of the Archbishop of Reims) from Hautvillers (France), c. 816-35, ink and tempera on vellum, 10 1/4″ x 8 1/4″ (Bibliothèque Municipale, Épernay)

Cite this page as: Dr. Nancy Ross and Dr. Jennifer Awes Freeman, “Saint Matthew from the Ebbo Gospels,” in Smarthistory, December 10, 2015, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/saint-matthew-from-the-ebbo-gospels/.

Cover of the Lindau Gospels

Jeweled upper cover of the Lindau Gospels, c. 880, Court School of Charles the Bald, 350 x 275 mm, cover may have been made in the Royal Abbey of St. Denis (Morgan Library and Museum, New York)

Cite this page as: Dr. Nancy Ross and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Lindau Gospels cover,” in Smarthistory, December 10, 2015, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/lindau-gospels-cover/.