India: Early Buddhist Art (beginning in the 3rd century BCE)

Introduction to Buddhism

Buddhisms

When we talk about the religion that worships the Buddha, we refer to it as singular: Buddhism. However, it may be more accurate to talk about “Buddhisms.” The religion that originated in India took on so many different forms and adapted in such a variety ways that it is often difficult to see how the various sects of Buddhism are related. What do they all have in common? The worship of the Buddha, of course! But who was Buddha? Was Buddha a man or a god? In early forms of Buddhism, Buddha is most definitely a man. As the religion changes and adapts, the Buddha is deified.

Origins

Buddhism originated in what is today modern India, where it grew into an organized religion practiced by monks, nuns, and lay people. Its beliefs were written down forming a large canon. Buddhist images were also devised to be worshiped in sacred spaces. From India, Buddhism spread throughout Asia.

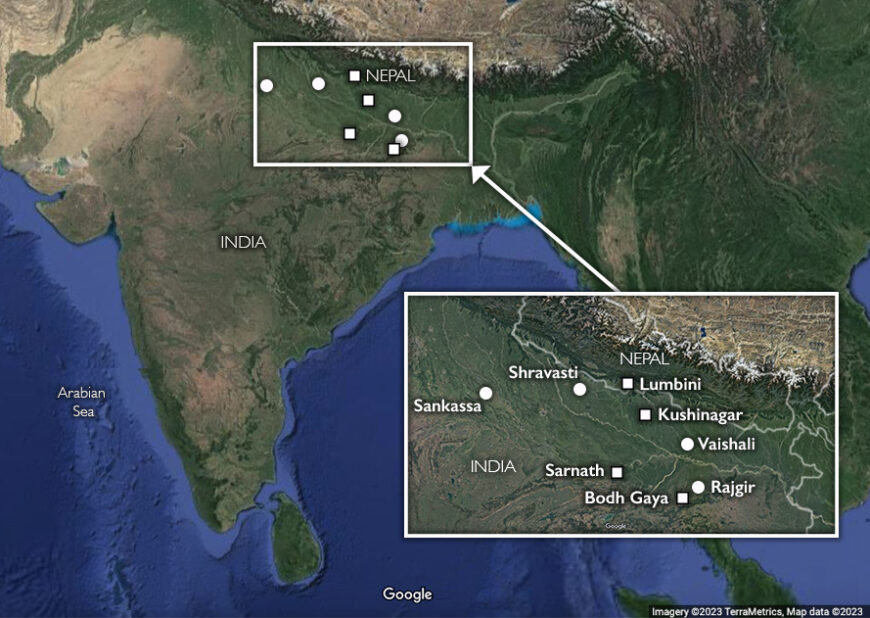

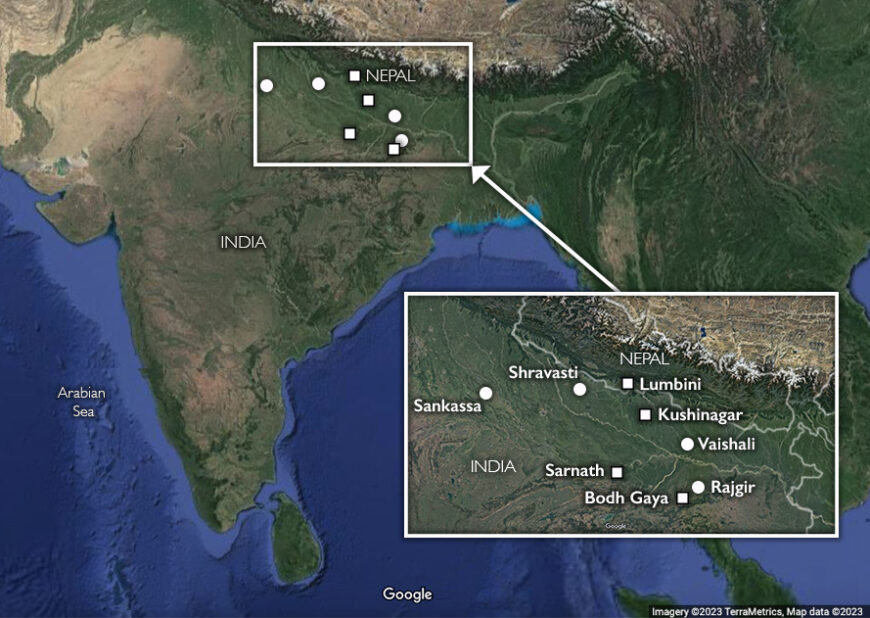

The Eight Great Places of Buddhism (Four Great Places are plotted as squares) (underlying map © Google)

In order to appreciate the magnitude of the Buddha’s achievement, we should try to imagine what life was like in early India, particularly in towns and villages of the Ganges River Valley—like Kapilavastu in the foothills of the Himalayan mountains—in what is now the country of Nepal. This is the area in which the Buddha was likely born, in about 560 B.C.E. Every year the river flooded the valley destroying crops. Monsoons came every year too, creating famine. There were also severe droughts and diseases such as dysentery and cholera.

The Brahmanas chanted the Vedic hymns and offered fire sacrifices to Brahma. However, they did not improve conditions for the common man. From the earliest times, Hindu society was stratified. Castes were firmly established in the economy with the Brahmanas the creators and perpetuators of a social order highly favorable to themselves.

Seated Buddha, 200–300, Pakistan, perhaps Jamalgarhi, Peshawar valley, ancient region of Gandhara, schist, 86.4 cm high (Asian Art Museum; photo: Ismoon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Middle Way

One of the Buddha’s greatest spiritual accomplishments was the doctrine of the Middle Way. He discovered the doctrine of the Middle Way only after he lived as an ascetic for some time. This experience convinced him that one should shun extremes. One should avoid the pursuit of worldly desires on the one hand and severe, ascetic discipline on the other. Despite his doubts about existing religious practices, and his strong sense of mission, he did not think of himself as the creator of a new religion. Rather, he felt the need to purify the religion of his day.

Buddha took for granted the truth of cosmological perspectives indigenous to the Indus valley—the worldview that is often associated with Hindu conceptions. One must understand what time and space look like in the Buddhist framework of ancient India. This framework was shared by all, whether one was an adherent of Brahmanism, Jainism, or Buddhism.

Samsara and time

Samsara (a Sanskrit word) literally means a “round” or a “cycle.” In the ancient Indian worldview this means the endless cycle of rebirth and death—there is no beginning and no end. This endless cycle is governed by karma (causality).

In ancient India, time is measured in kalpa. There is an unending cycle of Destruction, Rubble, Renovation, and Duration. Each period is 20 kalpa long and they are thought of as a circle.

- Destruction: Has a great beginning, but gets progressively worse. There are scourges of fire, water, wind.

- Rubble: Space is dark and empty, only wind exists in this stage, with seeds of karma.

- Renovation: This is the phase when things build up from the bottom.

- 4. Earth 3. Metal 2. Water 1. Wind

- Whirling wind forms a disk of water. Impurities float to the top and form a disk of metal. This disk breaks down and forms the earth.

- Duration: This is the phase of preservation, and at the end of this phase, sentient beings appear.

Space

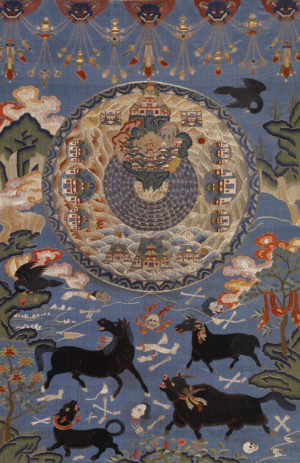

Mount Sumeru (or Meru) is the cosmic axis—that is, the link between heaven and earth. The Mountain is the center of the world in this cosmological conception, both physically and in terms of importance. On top of Mount Sumeru are the palaces of the gods. Mount Sumeru is surrounded by seven chains of mountains and an ocean that has four continents: North = rectangle; West = circle; South = trapezoid (Jambudvipa, where humans live); East = crescent moon.

The Universe is vertically structured. At the top is the realm of “no form.” This realm has no qualities that can be perceived by the senses. It is impossible to have a conception of it. Next are the realms of form that can be perceived in various states of meditation. One can see pleasant sights, bright light, and perceive coolness.

Below is the realm of desire. This realm has six levels. This is our realm. The six levels are the six paths of rebirth. The highest realm is that of the gods (deva). Halfway between gods and humans are demi-gods (asura). Humans and animals dwell on the surface of Jambudvipa. Hungry ghosts inhabit the shadow world below the animals. This level has much pain and suffering. Beings here are always hungry and never satiated. Hell beings occupy the lowest level. There are 8 levels within this level. At the eighth and lowest level there is no rest between tortures.

Karma

How do people (beings) move about in this world? The answer is karma. Karma is the law that regulates all life in samsara. Existence in time and space is ruled by karma. Karma means action or deed. Every action has a result. Every deed has an effect. Karma is a built-in universe scale for good and evil—good leads to good result and vice versa. Karma governs the long-term and the short-term. Karma is never destroyed. In the short term good deeds lead to a good result and bad deeds lead to a bad result. Karma transgresses from one life to another. It determines how a being will be reborn (higher or lower). Karma is not predestination because the concept of predestination does not take into account free will. Your current circumstances are determined by deeds in your previous life, but between the present and the future, there is free will. Upward mobility is possible.

What are the implications of the Buddhist world view? Being reborn a human is rare and important—rare especially in the time of Buddha. Buddha is born only in a small time period within the phase of destruction. We are fortunate to have access to his teachings since there is limited time and place to be given the chance to encounter Buddha. A being can only encounter Buddha and benefit in the human realm.

Nirvana

How does one achieve salvation? All is impermanent. All is cyclical. All is painful. Even gods suffer. They are only gods for one lifetime and then they are reborn lower down. Also gods do not have access to Buddha. Beings need to find a way out of the endless cycle of rebirth. The goal is Nirvana. Nirvana is extinction. Nirvana is the traditional name for that which is not samsara. Where is Nirvana? Nowhere. Nirvana is outside the vertical concept of the universe.

Cite this page as: Dr. Jennifer N. McIntire, “Introduction to Buddhism,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed May 29, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-buddhism/.

The Historical Buddha

Seated Buddha, 15th century (Thailand, Sukhothai style), bronze, 68.6 x 48.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A human endeavor

Among the founders of the world’s major religions, the Buddha was the only teacher who did not claim to be other than an ordinary human being. Other teachers were either God or directly inspired by God. The Buddha was simply a human being and he claimed no inspiration from any God or external power. He attributed all his realization, attainments, and achievements to human endeavor and human intelligence. A man and only a man can become a Buddha. Every man has within himself the potential of becoming a Buddha if he so wills it and works at it. Nevertheless, the Buddha was such a perfect human that he came to be regarded in popular religion as super-human.

Man’s position, according to Buddhism, is supreme. Man is his own master and there is no higher being or power that sits in judgment over his destiny. If the Buddha is to be called a “savior” at all, it is only in the sense that he discovered and showed the path to liberation, to Nirvana, the path we are invited to follow ourselves.

It is with this principle of individual responsibility that the Buddha offers freedom to his disciples. This freedom of thought is unique in the history of religion and is necessary because, according to the Buddha, man’s emancipation depends on his own realization of Truth, and not on the benevolent grace of a God or any external power as a reward for his obedient behavior.

Life of the Buddha

The main events of the Buddha’s life are well known. He was born Siddhartha Gautama of the Shaka clan. He is said to have had a miraculous birth, precocious childhood, and a princely upbringing. He married and had a son.

He encountered an old man, a sick man, a corpse, and a religious ascetic. He became aware of suffering and became convinced that his mission was to seek liberation for himself and others. He renounced his princely life, spent six years studying doctrines and undergoing yogic austerities. He then gave up ascetic practices for normal life. He spent seven weeks in the shade of a Bodhi tree until, finally, one night toward dawn, enlightenment came. Then he preached sermons and embarked on missionary travels for 45 years. He affected the lives of thousands—high and low. At the age of 80 he experienced his parinirvana—extinction itself.

Death of the Buddha, late 17th–early 18th century, ink, colors, and gold on silk hanging scroll, 331.5 x 229 cm, Japan (Art Institute of Chicago)

This is the most basic outline of his life and mission. The literature inspired by the Buddha’s story is as various as those who have told it in the last 2500 years. To the first of his followers, and the tradition associated with Theravada Buddhism and figures like the great Emperor Ashoka, the Buddha was a man, not a God. He was a teacher, not a savior. To this day the Theravada tradition prevails in parts of India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Thailand.

To those who, a few hundred years later, formed the Mahayana School, Buddha was a savior and often a God—a God concerned with man’s sorrows above all else. The Mahayana form of Buddhism is in Tibet, Mongolia, Vietnam, Korea, China, and Japan. The historical Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama) is also known as Shakyamuni.

Cite this page as: Dr. Jennifer N. McIntire, “The historical Buddha,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed May 29, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-historical-buddha/.

The Pillars of Ashoka

Ashokan pillar, c. 279 B.C.E. – 232 B.C.E, Vaishali, India (where Buddha preached his last sermon). Photo: Rajeev Kumar, CC: BY-SA 2.5)

A Buddhist king

What happens when a powerful ruler adopts a new religion that contradicts the life into which he was born? What about when this change occurs during the height of his rule when things are pretty much going his way? How is that information conveyed over a large geographical region with thousands of inhabitants?

King Ashoka, who many believe was an early convert to Buddhism, decided to solve these problems by erecting pillars that rose some 50 feet into the sky. The pillars were raised throughout the Magadha region in the North of India that had emerged as the center of the first Indian empire, the Mauryan Dynasty (322-185 B.C.E). Written on these pillars, intertwined in the message of Buddhist compassion, were the merits of King Ashoka.

The third emperor of the Mauryan dynasty, Ashoka (pronounced Ashoke), who ruled from c. 279 B.C.E. – 232 B.C.E., was the first leader to accept Buddhism and thus the first major patron of Buddhist art.[1] Ashoka made a dramatic conversion to Buddhism after witnessing the carnage that resulted from his conquest of the village of Kalinga. He adopted the teachings of the Buddha known as the Four Noble Truths, referred to as the dharma (the law):

Life is suffering (suffering=rebirth)

the cause of suffering is desire

the cause of desire must be overcome

when desire is overcome, there is no more suffering (suffering=rebirth)

Individuals who come to fully understand the Four Noble Truths are able to achieve Enlightenment, ending samsara, the endless cycle of birth and rebirth. Ashoka also pledged to follow the Six Cardinal Perfections (the Paramitas), which were codes of conduct created after the Buddha’s death providing instructions for the Buddhist practitioners to follow a compassionate Buddhist practice. Ashoka did not require that everyone in his kingdom become Buddhist, and Buddhism did not become the state religion, but through Ashoka’s support, it spread widely and rapidly.

The pillars

Ashokan pillar capital at Vaishali, Bihar, India, c. 250 B.C.E. (photo: mself, CC BY-SA 2.5)

One of Ashoka’s first artistic programs was to erect the pillars that are now scattered throughout what was the Mauryan empire. The pillars vary from 40 to 50 feet in height. They are cut from two different types of stone—one for the shaft and another for the capital. The shaft was almost always cut from a single piece of stone. Laborers cut and dragged the stone from quarries in Mathura and Chunar, located in the northern part of India within Ashoka’s empire. The pillars weigh about 50 tons each. Only 19 of the original pillars survive and many are in fragments. The first pillar was discovered in the sixteenth century.

Lotus and lion

The physical appearance of the pillars underscores the Buddhist doctrine. Most of the pillars were topped by sculptures of animals. Each pillar is also topped by an inverted lotus flower, which is the most pervasive symbol of Buddhism (a lotus flower rises from the muddy water to bloom unblemished on the surface—thus the lotus became an analogy for the Buddhist practitioner as he or she, living with the challenges of everyday life and the endless cycle of birth and rebirth, was able to achieve Enlightenment, or the knowledge of how to be released from samsara, through following the Four Noble Truths). This flower, and the animal that surmount it, form the capital, the topmost part of a column. Most pillars are topped with a single lion or a bull in either seated or standing positions. The Buddha was born into the Shakya or lion clan. The lion, in many cultures, also indicates royalty or leadership. The animals are always in the round and carved from a single piece of stone.

Ashoka Pillar at Lumbini, Nepal, the birthplace of the Buddha (photo: Charlie Phillips, CC: BY 2.0)

The edicts

Some pillars had edicts (proclamations) inscribed upon them. The edicts were translated in the 1830s. Since the seventeenth century, 150 Ashokan edicts have been found carved into the face of rocks and cave walls as well as the pillars, all of which served to mark his kingdom, which stretched across northern India and south to below the central Deccan plateau and in areas now known as Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan. The rocks and pillars were placed along trade routes and in border cities where the edicts would be read by the largest number of people possible. They were also erected at pilgrimage sites such as at Bodh Gaya, the place of Buddha’s Enlightenment, and Sarnath, the site of his First Sermon and Sanchi, where the Mahastupa, the Great Stupa of Sanchi, is located (a stupa is a burial mound for an esteemed person. When the Buddha died, he was cremated and his ashes were divided and buried in several stupas. These stupas became pilgrimage sites for Buddhist practitioners).

Some pillars were also inscribed with dedicatory inscriptions, which firmly date them and name Ashoka as the patron. The script was Brahmi, the language from which all Indic language developed. A few of the edicts found in the western part of India are written in a script that is closely related to Sanskrit and a pillar in Afghanistan is inscribed in both Aramaic and Greek—demonstrating Ashoka’s desire to reach the many cultures of his kingdom. Some of the inscriptions are secular in nature. Ashoka apologizes for the massacre in Kalinga and assures the people that he now only has their welfare in mind. Some boast of the good works that Ashoka has done, underscoring his desire to provide for his people.

The Hinayana period

Ashokan Pillar on a relief at the Mahastupa at Sanchi, north gate (torana) post, 3rd c. B.C.E. (photo: Nandanupadhyay, CC: BY-SA 3.0)

The pillars (and the stupas) were created in the Hinayana (Lesser Vehicle) period. Hinayana is the first stage of Buddhism, roughly dated from the sixth c. to the first century B.C.E., in which no images of the Buddha were made. The memory of the historical Buddha and his teachings was enough to sustain the practitioners. But several symbols became popular as stand-ins for the human likeness of the Buddha. The lotus, as noted above, is one. The lion, which is typically seen on the Ashokan pillars, is another. The wheel (cakra) is a symbol of both samsara, the endless circle of birth and rebirth, and the dharma, the Four Noble Truths.

Why a pillar?

There are a few hypotheses about why Ashoka used the pillar as a means for communicating his Buddhist message. It is quite possible that Persian artists came to Ashoka’s empire in search of work, bringing with them the form of the pillar, which was common in Persian art. But it is also likely that Ashoka chose the pillar because it was already an established Indian art form. In both Buddhism and Hinduism, the pillar symbolized the axis mundi (the axis on which the world spins).

The pillars and edicts represent the first physical evidence of the Buddhist faith. The inscriptions assert Ashoka’s Buddhism and support his desire to spread the dharma throughout his kingdom. The edicts say nothing about the philosophical aspects of Buddhism and scholars have suggested that this demonstrates that Ashoka had a very simple and naïve understanding of the dharma. But, as Ven S. Dhammika suggests, Ashoka’s goal was not to expound on the truths of Buddhism, but to inform the people of his reforms and encourage them to live a moral life. The edicts, through their strategic placement and couched in the Buddhist dharma, serve to underscore Ashoka’s administrative role as a tolerant leader.

Edict #6 is a good example:

“Beloved of the Gods speaks thus: Twelve years after my coronation

I started to have Dhamma edicts written for the welfare and happiness of the people, and so that not transgressing them they might grow in the Dhamma. Thinking: “How can the welfare and happiness of the people be secured?” I give my attention to my relatives, to those dwelling far, so I can lead them to happiness and then I act accordingly. I do the same for all groups. I have honored all religions with various honors. But I consider it best to meet with people personally.”

Footnotes

[1] The details and extent to which Emperor Ashoka was a practicing Buddhist is a topic debated by scholars, though it is widely accepted that he was the first major patron of Buddhist art on the Indian subcontinent. For more discussions as to whether or not Ashoka was a “secular” ruler, see Akeel Bilgrami, ed.,Beyond the Secular West (Columbia University Press, 2016); Charles Taylor and Alfred Stepan, eds., Boundaries of Toleration: Religion, Culture, and Public Life (Columbia University Press, 2014); and Ashis Nandy, “The Politics of Secularism and the Recovery of Religious Tolerance,” Alternatives XIII (1988), pp. 177-194. For more on Ashoka’s relationship with the Buddhist community and doctrine, see Alf Hiltebeitel, “King Asoka’s Dhamma,” in Dharma (University of Hawai’i Press, 2010), pp. 12-18 and John S. Strong, The Legend of King Asoka: A Study and Translation of the Asokavadana (Princeton University Press, 1983).

Cite this page as: Dr. Karen Shelby, “The Pillars of Ashoka,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed May 29, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-pillars-of-ashoka/.

The Lion Capital at Sarnath

Lion Capital, Ashokan Pillar at Sarnath, c. 250 B.C.E., polished sandstone, 210 x 283 cm (Archaeological Museum Sarnath, India; photo: पाटलिपुत्र, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Site of Buddha’s First Sermon

The most celebrated of the Ashokan pillars is the one erected at Sarnath, the site of Buddha’s First Sermon where he shared the Four Noble Truths (the dharma or the law). Currently, the pillar remains where it was originally sunk into the ground, but the capital is now on display at the Sarnath Museum. It is this pillar that was adopted as the national emblem of India. It is depicted on the one rupee note and the two rupee coin.

The pillar

The pillar is a symbol of the axis mundi and of the column that rises every day at noon from the legendary Lake Anavatapta to touch the sun.

Two Rupees Commemorative Coin issued in 2000 on the 50th Anniversary of the Supreme Court of India (photo: P. L. Tandon, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The capital

The top of the column—the capital—has three parts. First, a base of a lotus flower, the most ubiquitous symbol of Buddhism.

Then, a drum on which four animals are carved represents the four cardinal directions: a horse (west), an ox (east), an elephant (south), and a lion (north). They also represent the four rivers that leave Lake Anavatapta and enter the world as the four major rivers. Each of the animals can also be identified by each of the four perils of samsara. The moving animals follow one another, endlessly turning the wheel of existence.

Four lions stand atop the drum, each facing in the four cardinal directions. Their mouths are open, roaring or spreading the dharma, the Four Noble Truths, across the land. The lion references the Buddha, formerly Shakyamuni, a member of the Shakya (lion) clan. The lion is also a symbol of royalty and leadership and may also represent the Buddhist king Ashoka who ordered these columns. A cakra (wheel) was originally mounted above the lions.

Some of the lion capitals that survive have a row of geese carved below the lions. The goose is an ancient Vedic symbol. The flight of the goose is thought of as a link between the earthly and heavenly spheres.

Lion Capital, Ashokan Pillar at Sarnath, c. 250 B.C.E., polished sandstone, 210 x 283 cm, Sarnath Museum, India (photo: Shyamal)

The pillar reads from bottom to top. The lotus represents the murky water of the mundane world, and the four animals remind the practitioner of the unending cycle of samsara as we remain, through our ignorance and fear, stuck in the material world. But the cakras between them offer the promise of the Eightfold Path that guides one to the unmoving center at the hub of the wheel. Note that in these particular cakras, the number of spokes in the wheel (eight for the Eightfold Path), had not yet been standardized.

The lions are the Buddha himself from whom the knowledge of release from samsara is possible. And the cakra that once stood at the apex represents moksa, the release from samsara. The symbolism of moving up the column toward Enlightenment parallels the way in which the practitioner meditates on the stupa in order to attain the same goal.

Cite this page as: Dr. Karen Shelby, “Lion Capital, Ashokan Pillar at Sarnath,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed May 29, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/lion-capital-ashokan-pillar-at-sarnath/.

The Stupa, an Introduction

Can a mound of dirt represent the Buddha, the path to Enlightenment, a mountain, and the universe all at the same time? It can if its a stupa.

Video from the Asian Art Museum

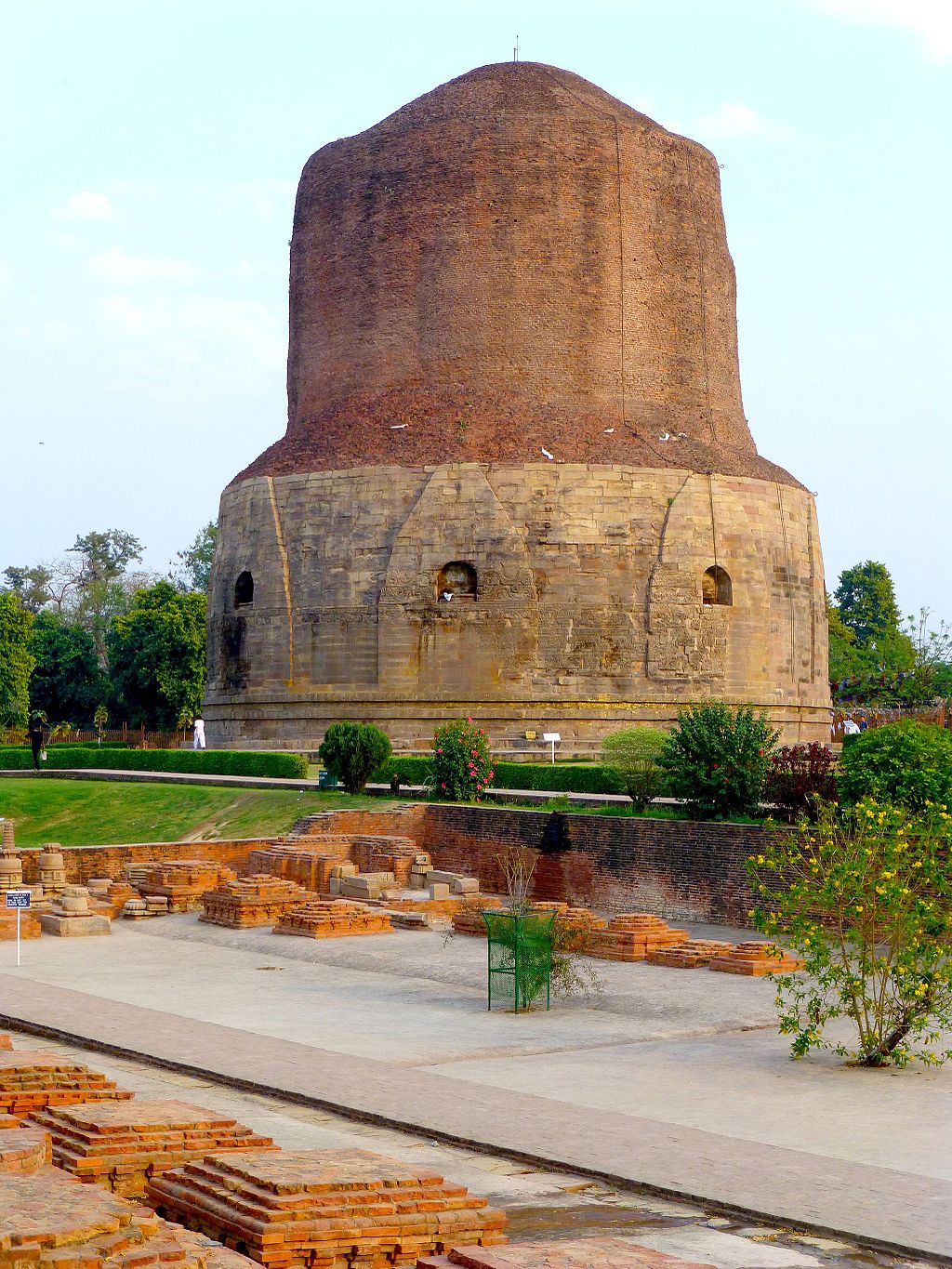

The stupa (“stupa” is Sanskrit for heap) is an important form of Buddhist architecture, though it predates Buddhism. It is generally considered to be a sepulchral monument—a place of burial or a receptacle for religious objects. At its simplest, a stupa is a dirt burial mound faced with stone. In Buddhism, the earliest stupas contained portions of the Buddha’s ashes, and as a result, the stupa began to be associated with the body of the Buddha. Adding the Buddha’s ashes to the mound of dirt activated it with the energy of the Buddha himself.

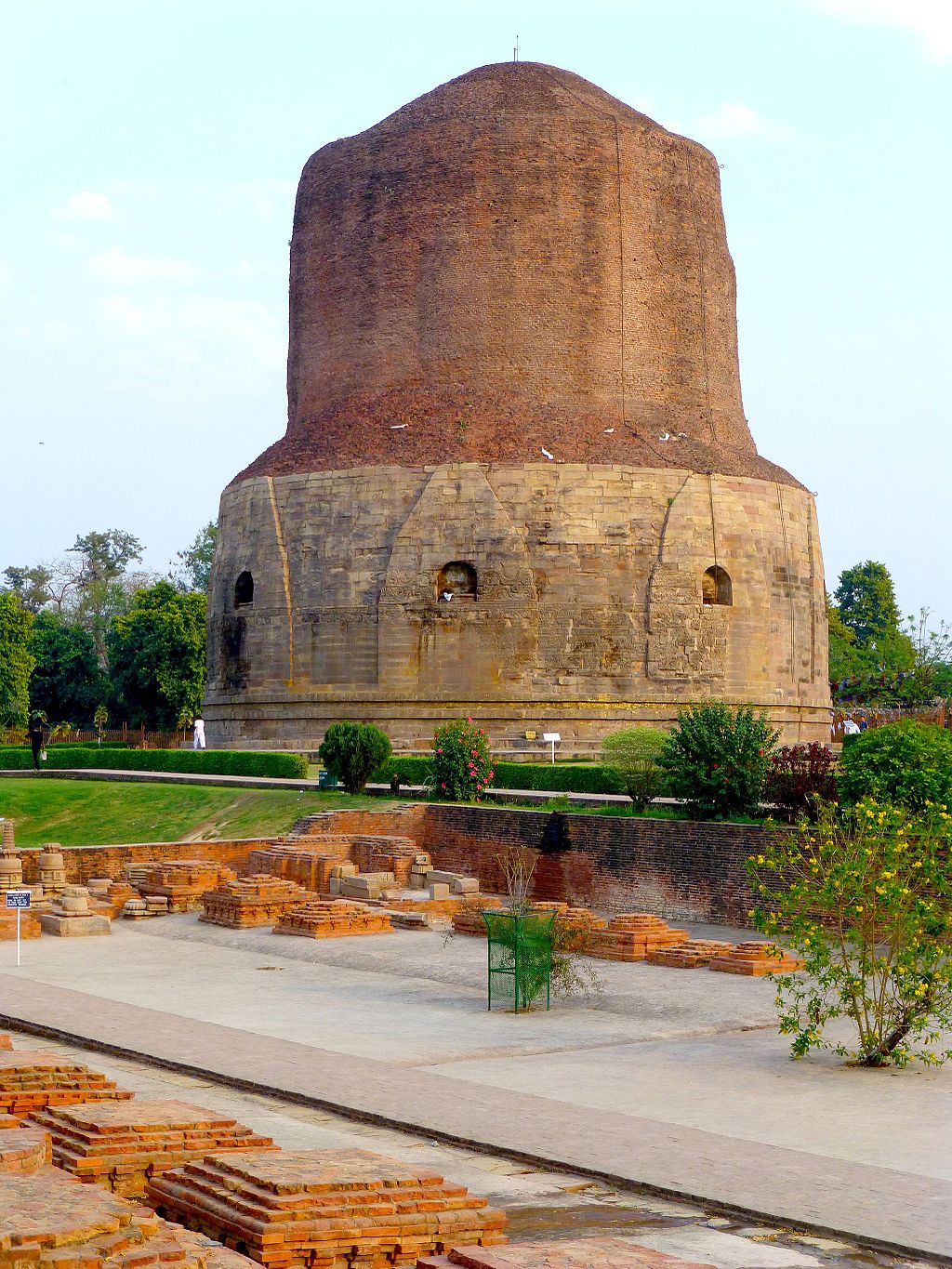

Dhamek Stupa, c. 5th–6th century (Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, India) (photo: Anandajoti Bhikkhu, CC BY 2.0)

Early stupas

Before Buddhism, great teachers were buried in mounds. Some were cremated, but sometimes they were buried in a seated, meditative position. The mound of earth covered them up. Thus, the domed shape of the stupa came to represent a person seated in meditation much as the Buddha was when he achieved Enlightenment and knowledge of the Four Noble Truths. The base of the stupa represents his crossed legs as he sat in a meditative pose (called padmasana or the lotus position). The middle portion is the Buddha’s body and the top of the mound, where a pole rises from the apex surrounded by a small fence, represents his head. Before images of the human Buddha were created, reliefs often depicted practitioners demonstrating devotion to a stupa.

The ashes of the Buddha were buried in stupas built at locations associated with important events in the Buddha’s life including Lumbini (where he was born), Bodh Gaya (where he achieved Enlightenment), Deer Park at Sarnath (where he preached his first sermon sharing the Four Noble Truths), and Kushingara (where he died). The choice of these sites and others were based on both real and legendary events.

Remains of the Ashokan Pillar to right of the Southern Gateway of the Great Stupa, with edict, c. 260 B.C.E. (Sanchi, India) (photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY 3.0)

“Calm and glad”

According to legend, King Ashoka, who was the first king to embrace Buddhism, created 84,000 stupas and divided the Buddha’s ashes among them all. While this is an exaggeration (and the stupas were built by Ashoka some 250 years after the Buddha’s death), it is clear that Ashoka was responsible for building many stupas all over northern India and the other territories under the Mauryan Dynasty in areas now known as Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan.

One of Ashoka’s goals was to provide new converts with the tools to help with their new faith. In this, Ashoka was following the directions of the Buddha who, prior to his death (parinirvana), directed that stupas should be erected in places other than those associated with key moments of his life so that “the hearts of many shall be made calm and glad.” Ashoka also built stupas in regions where the people might have difficulty reaching the stupas that contained the Buddha’s ashes.

One of the most famous stupas, the Great Stupa (Mahastupa) in Madya Pradesh, India was built at the birthplace of Ashoka’s wife, Devi, daughter of a local merchant in the village of Sanchi located on an important trade route (photo: Nagarjun Kandukuru, CC BY 2.0)

Karmic benefits

The practice of building stupas spread with the Buddhist doctrine to Nepal and Tibet, Bhutan, Thailand, Burma, China, and the United States where large Buddhist communities are centered. While stupas have changed in form over the years, their function remains essentially unchanged. Stupas remind the Buddhist practitioner of the Buddha and his teachings almost 2,500 years after his death.

For Buddhists, building stupas also has karmic benefits. Karma, a key component in both Hinduism and Buddhism, is the energy generated by a person’s actions and the ethical consequences of those actions. Karma affects a person’s next existence or re-birth. For example, in the Avadāna Sutra ten merits of building a stupa are outlined. One states that if a practitioner builds a stupa he or she will not be reborn in a remote location and will not suffer from extreme poverty. As a result, a vast number of stupas dot the countryside in Tibet (where they are called chorten) and in Burma (chedi).

The journey to Enlightenment

Buddhists visit stupas to perform rituals that help them to achieve one of the most important goals of Buddhism: to understand the Buddha’s teachings, known as the Four Noble Truths (also known as the dharma and the law) so when they die they cease to be caught up in samsara, the endless cycle of birth and death.

- The Four Noble Truths:

1. Life is suffering (suffering=rebirth).

2. The cause of suffering is desire.

3. The cause of desire must be overcome.

4. When desire is overcome, there is no more suffering (suffering=rebirth).

Once individuals come to fully understand the Four Noble Truths, they are able to achieve Enlightenment, or the complete knowledge of the dharma. In fact, Buddha means “the Enlightened One” and it is the knowledge that the Buddha gained on his way to achieving Enlightenment that Buddhist practitioners seek on their own journey toward Enlightenment.

The circle or wheel

One of the early sutras (a collection of sayings attributed to the Buddha forming a religious text) records that the Buddha gave specific directions regarding the appropriate method of honoring his remains (the Maha-parinibbāna sutra): his ashes were to be buried in a stupa at the crossing of the mythical four great roads (the four directions of space), the unmoving hub of the wheel, the place of Enlightenment.

If one thinks of the stupa as a circle or wheel, the unmoving center symbolizes Enlightenment. Likewise, the practitioner achieves stillness and peace when the Buddhist dharma is fully understood. Many stupas are placed on a square base, and the four sides represent the four directions: north, south, east, and west. Each side often has a gate in the center, which allows the practitioner to enter from any side. The gates are called torana. Each gate also represents the four great life events of the Buddha: East (Buddha’s birth), South (Enlightenment), West (First Sermon where he preached his teachings or dharma), and North (Nirvana). The gates are turned at right angles to the axis mundi to indicate movement in the manner of the arms of a svastika, a directional symbol that, in Sanskrit, means “to be good” (“su” means good or auspicious and “asti” means to be). The torana are directional gates guiding the practitioner in the correct direction on the correct path to Enlightenment, the understanding of the Four Noble Truths.

Yasti (detail), Stupa 1, Sanchi, India (photo: Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A microcosm of the universe

At the top of stupa is a yasti, or spire, which symbolizes the axis mundi (a line through the earth’s center around which the universe is thought to revolve). The yasti is surrounded by a harmika, a gate or fence, and is topped by chattras (umbrella-like objects symbolizing royalty and protection).

The stupa makes visible something that is so large as to be unimaginable. The axis symbolizes the center of the cosmos partitioning the world into six directions: north, south, east, west, the nadir, and the zenith. This central axis, the axis mundi, is echoed in the same axis that bisects the human body. In this manner, the human body also functions as a microcosm of the universe. The spinal column is the axis that bisects Mt. Meru (the sacred mountain at the center of the Buddhist world) and around which the world pivots. The aim of the practitioner is to climb the mountain of one’s own mind, ascending stage by stage through the planes of increasing levels of Enlightenment.

Annotated diagram of a stupa, Stupa 3, Sanchi, India (photo: Anandajoti Bhikkhu, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Circumambulation

The practitioner does not enter the stupa, it is a solid object. Instead, the practitioner circumambulates (walks around) it as a meditational practice focusing on the Buddha’s teachings. This movement suggests the endless cycle of rebirth (samsara) and the spokes of the Eightfold Path (eight guidelines that assist the practitioner) that leads to knowledge of the Four Noble Truths and into the center of the unmoving hub of the wheel, Enlightenment. This walking meditation at a stupa enables the practitioner to visualize Enlightenment as the movement from the perimeter of the stupa to the unmoving hub at the center marked by the yasti.

This video/animation shows the perspective of someone circumambulating the Mahastupa in Sanchi, the soundtrack plays monks chanting Buddhist prayers, an aid in meditation. Circumambulation is also a part of other faiths. For example, Muslims circle the Kaaba in Mecca and cathedrals in the West such at Notre Dame in Paris include a semicircular ambulatory (a hall that wraps around the back of the choir, around the altar).

The practitioner can walk to circumambulate the stupa or move around it through a series of prostrations (a movement that brings the practitioner’s body down low to the ground in a position of submission). An energetic and circular movement around the stupa raises the body’s temperature. Practitioners do this to mimic the heat of the fire that cremated the Buddha’s body, a process that burned away the bonds of self-hood and attachment to the mundane or ordinary world. Attachments to the earthly realm are considered obstacles in the path toward Enlightenment. Circumambulation is not veneration for the relics themselves—a distinction sometime lost on novice practitioners. The Buddha did not want to be revered as a god, but wanted his ashes in the stupas to serve as a reminder of the Four Noble Truths.

Votive Stupa, Bodhgaya, 8th century, stone, 78 x 44 x 35 cm (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; photo: Ethan Doyle White, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Votive offerings

Small stupas can function as votive offerings (objects that serve as the focal point for acts of devotion). In order to gain merit, to improve one’s karma, individuals could sponsor the casting of a votive stupa. Indian and Tibetan stupas typically have inscriptions that state that the stupa was made “so that all beings may attain Enlightenment.” Votive stupas can be consecrated and used in home altars or utilized in monastic shrines. Since they are small, they can be easily transported; votive stupas, along with small statues of the Buddha and other Buddhist deities, were carried across Nepal, over the Himalayas and into Tibet, helping to spread Buddhist doctrine. Votive stupas are often carved from stone or caste in bronze. The bronze stupas can also serve as a reliquary and ashes of important teachers can be encased inside.

This stupa clearly shows the link between the form of the stupa and the body of the Buddha. The Buddha is represented at his moment of Enlightenment, when he received the knowledge of the Four Noble Truths. He is making the earth touching gesture (bhumisparsamudra) and is seated in padmasan, the lotus position. He is seated in a gateway signifying a sacred space that recalls the gates on each side of monumental stupas.

The Stupa on Google Maps

Cite this page as: Dr. Karen Shelby, “The stupa,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed May 29, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-stupa/.