Early Byzantine Art after Constantine

Periods of Byzantine history

Early Byzantine (including Iconoclasm) c. 330–843

Middle Byzantine c. 843–1204

The Fourth Crusade & Latin Empire 1204–1261

Late Byzantine 1261–1453

Post-Byzantine after 1453

Santa Sabina, Rome, 422–432 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Basilicas and new forms

Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, c. 490, Ravenna, Italy (photo: Evan Freeman, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

After the time of Constantine, a standardized church architecture emerged, with the basilica for congregational worship dominating construction.

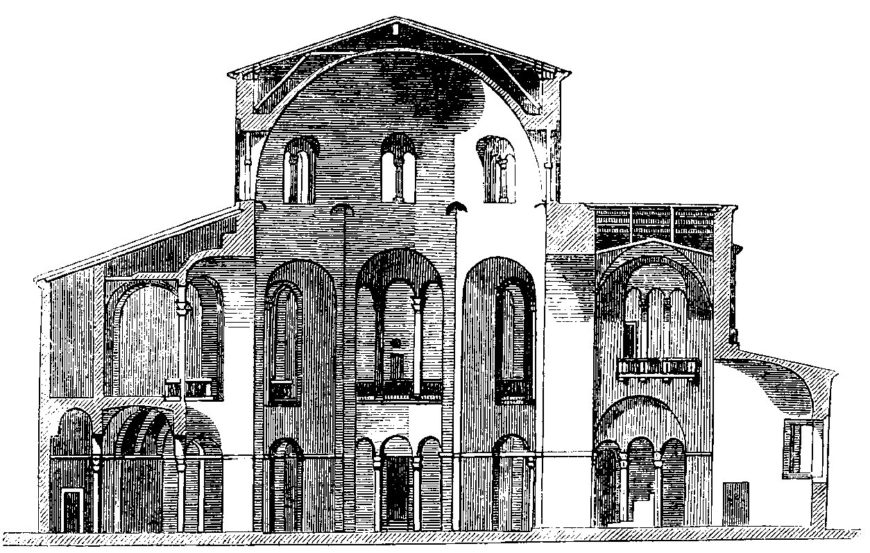

There were numerous regional variations: in Rome and the West, for example, basilicas usually were elongated without galleries, as at S. Sabina in Rome (522–32) or S. Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna (c. 490).

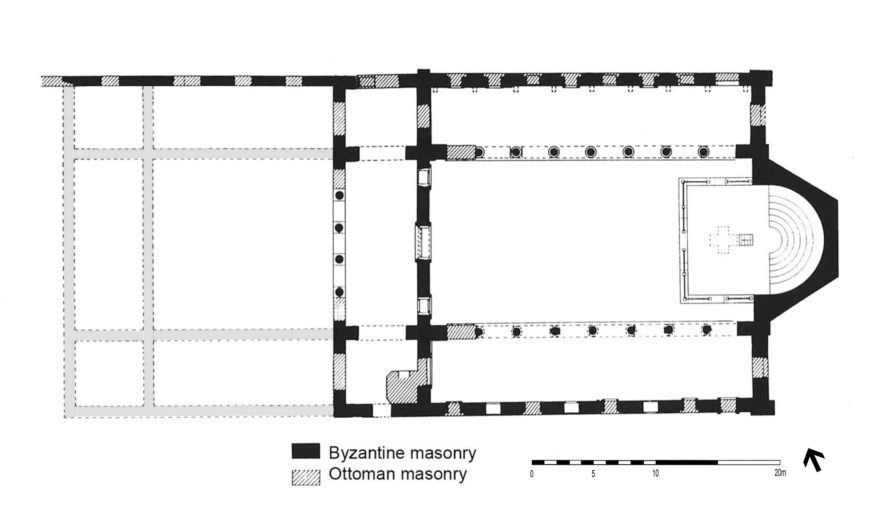

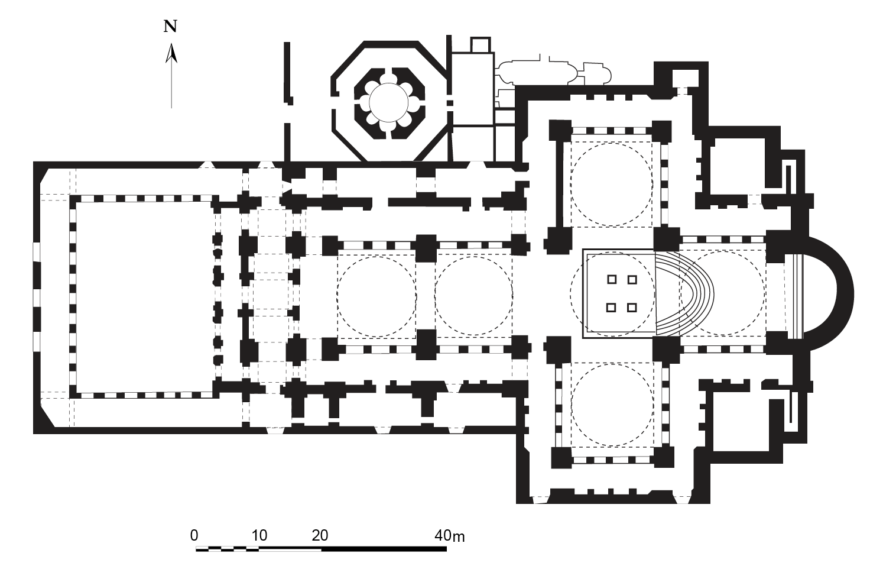

Plan of St. John Stoudios, 458, Constantinople (Istanbul) (© Robert Ousterhout)

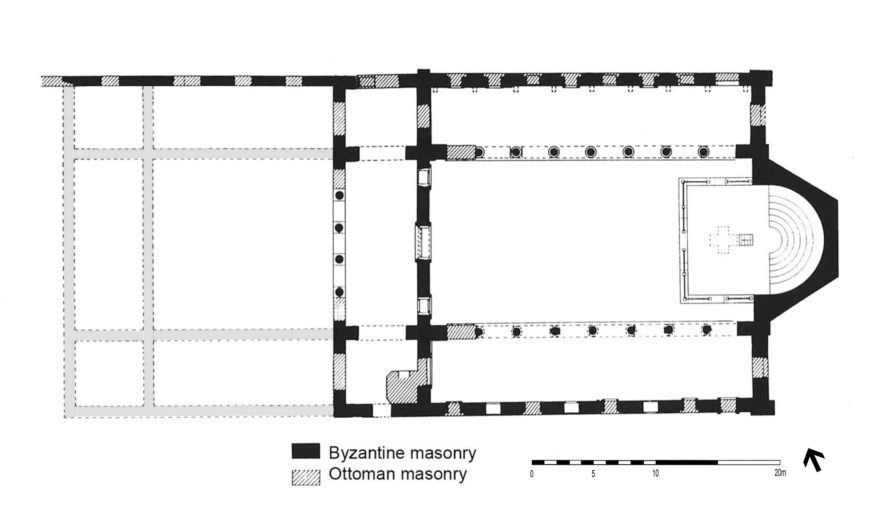

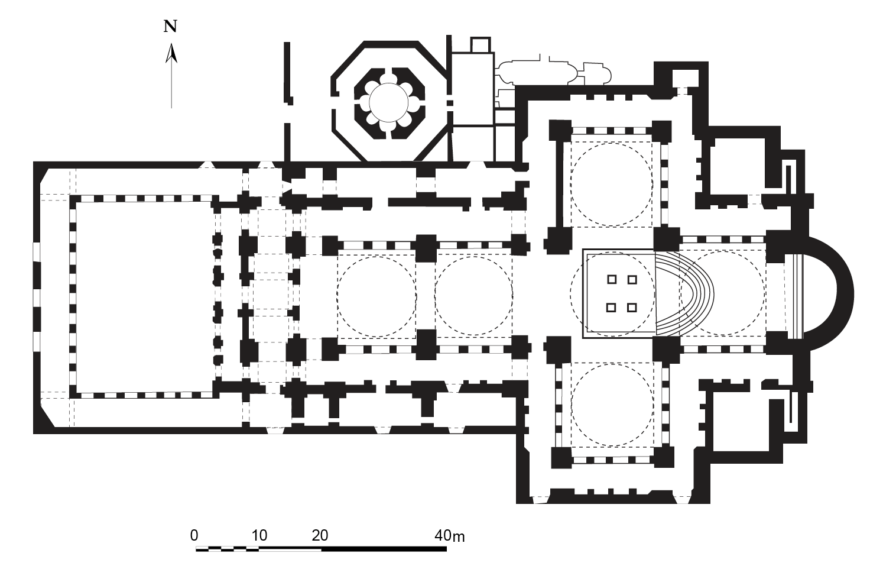

In the East the buildings were more compact and galleries were more common, as at St. John Stoudios in Constantinople (458) or the Achieropoiitos in Thessaloniki (early fifth century) (view plan and elevation).

Church of the Acheiropoietos, Thessaloniki, early 5th century (photo: Evan Freeman, CC BY-SA 4.0 )

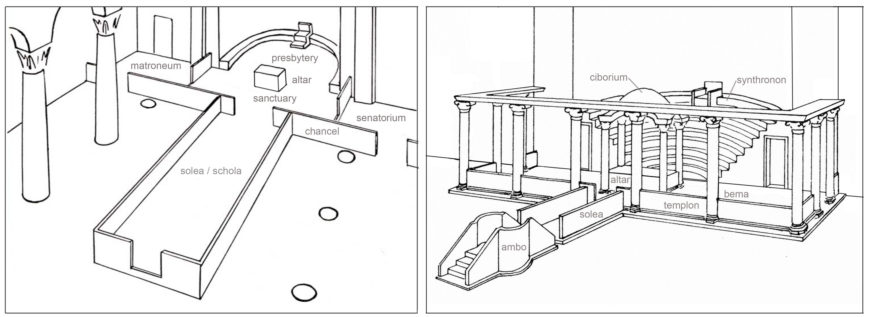

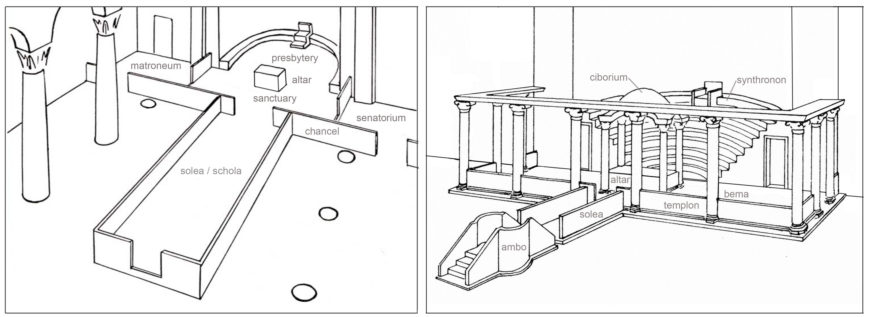

By the fifth century, the liturgy had become standardized, but, again, with some regional variations, evident in the planning and furnishing of basilicas. In general, the area of the altar was enclosed by a templon barrier, with semicircular seating for the officiants (the synthronon) in the curvature of the apse. The altar itself was covered by a ciborium. Within the nave, a raised pulpit or ambo provided a setting for the Gospel readings.

Left: diagram of an early Christian Roman sanctuary; right: diagram of an early Christian Constantinopolitan sanctuary (© Robert G. Ousterhout, adapted from T. F. Mathews, “An Early Roman Chancel Arrangement and Its Liturgical Uses,” 1962, and R. Naumann and H. Belting, Euphemia-Kirche, 1966)

Santo Stefano Rotondo, Rome, c. 468–83 (photo: Brad Hostetler, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The liturgy probably had less effect on the creation of new architectural designs than on the increasing symbolism and sanctification of the church building. Some new building types emerge, such as the cruciform church, the tetraconch, octagon, and a variety of centrally planned structures. Such forms may have had symbolic overtones; for example, the cruciform plan may be either a reflection of the church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople or associated with the life-giving cross, as at S. Croce in Ravenna or SS. Apostoli in Milan. Other innovative designs may have had their origins in architectural geometry, such as the enigmatic S. Stefano Rotondo (468–83) in Rome. The aisled tetraconch churches, once thought to be a form associated with martyria, are most likely cathedrals or metropolitan churches. The early fifth-century tetraconch in the Library of Hadrian in Athens was probably the first cathedral of the city; that at Selucia Pieria-Antioch, from the late fifth century, was possibly a metropolitan church.

Church furniture, left to right: restored templon, 10th century, Holy Apostles, Athens (Evan Freeman, CC BY-SA 4.0); synthronon, 6th c., Hagia Eirene, Constantinople (Evan Freeman, CC BY-SA 4.0); ciborium by Nicolaus Ranucius & sons, Italy, c. 1150 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); reconstructed ambo, 5th century (garden, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul) (Evan Freeman, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Orthodox (or Neonian) Baptistery, Ravenna, c. 400–450 (photo: Kirk K, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Baptisteries

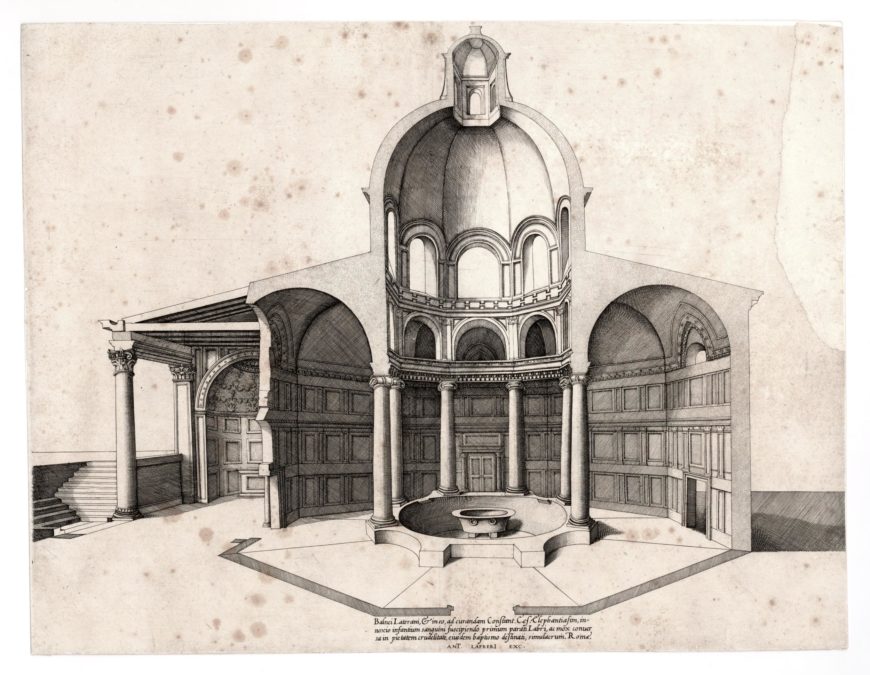

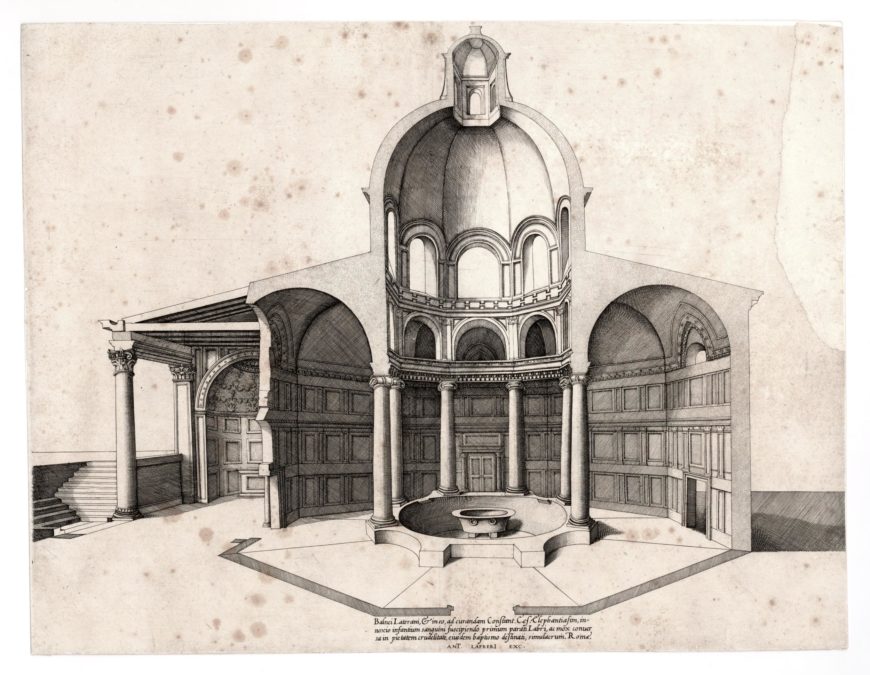

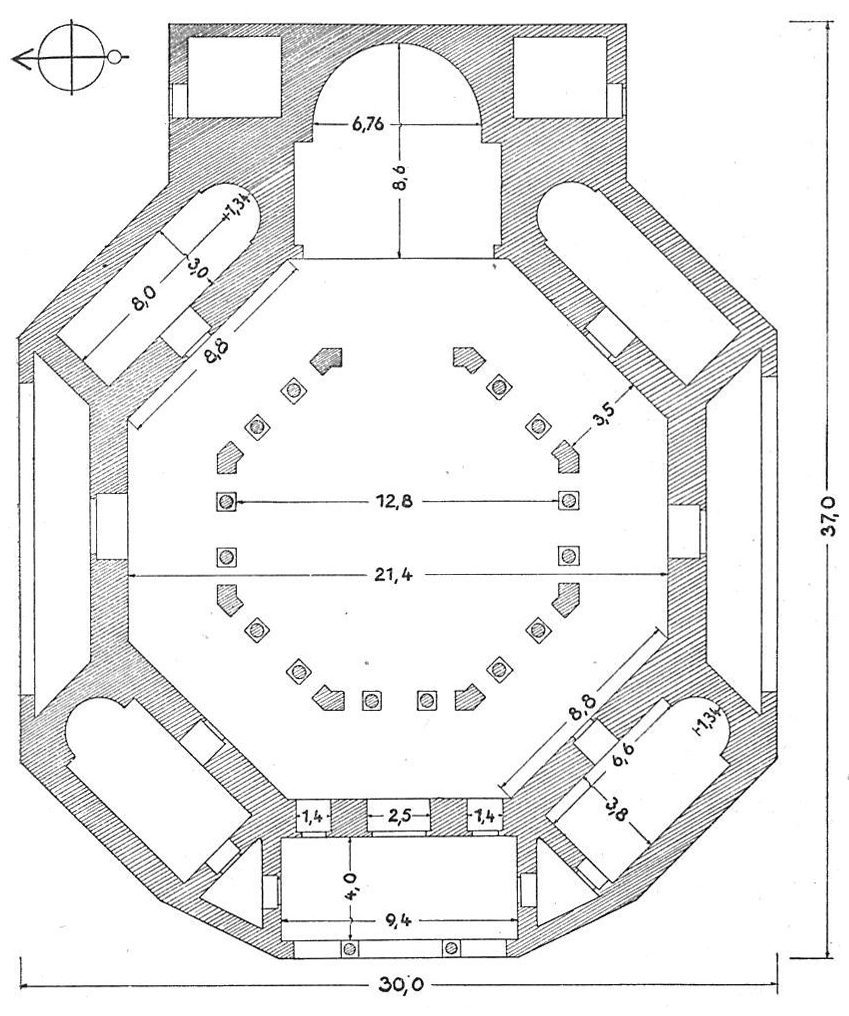

Baptisteries also appear as prominent buildings throughout the Empire, necessary for the elaborate ceremonies addressed to adult converts and catechumens. Most common was a symbolically resonant, octagonal building housing the font and attached to the cathedral, as with the Orthodox (or Neonian) Baptistery at Ravenna, c. 400–450. In Rome, the Lateran’s baptistery was an independent, octagonal structure that stood north of the basilica’s apse. Built under Constantine, the baptistery expanded under Pope Sixtus III in the fifth century with the addition of an ambulatory around its central structure. The inscription St. Ambrose composed for his baptistery at Milan clarifies the symbolism of such eight-sided buildings:

The eight-sided temple has risen for sacred purposes

The octagonal font is worthy for this task.

It is seemly that the baptismal hall should arise in this number

By which true health returns to people

By the light of the resurrected Christinscription attributed to St. Ambrose of Milan

Nicolas Beatrizet, Lateran Baptistery in Rome, reconstruction, 1550s, engraving (The British Museum)

Baptismal font, Vitalis Basilica Baptistery, Sbeitla, Tunisia, 6th century (photo: Kirk K, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Associated with death and resurrection, the planning type derives from Late Roman mausolea, although not directly from the Anastasis Rotunda. Variations abound: at Butrint (in modern Albania) and Nocera (in southwestern Italy), for example, the baptisteries have ambulatories; in North Africa, the architecture tends to remain simple, while the form of the font is elaborated. With the change to infant baptism and a simplified ceremony, however, monumental baptisteries cease to be constructed after the sixth century.

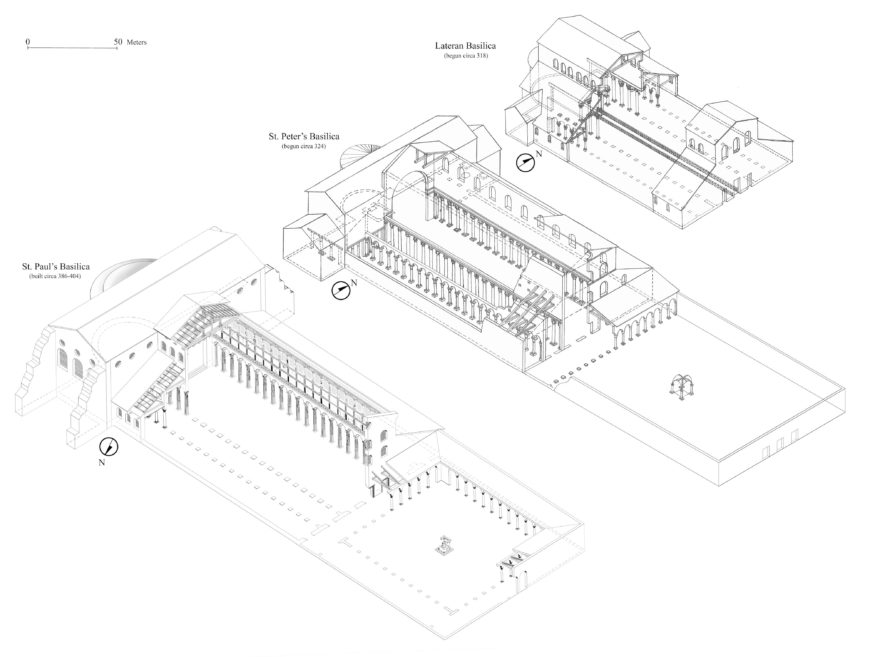

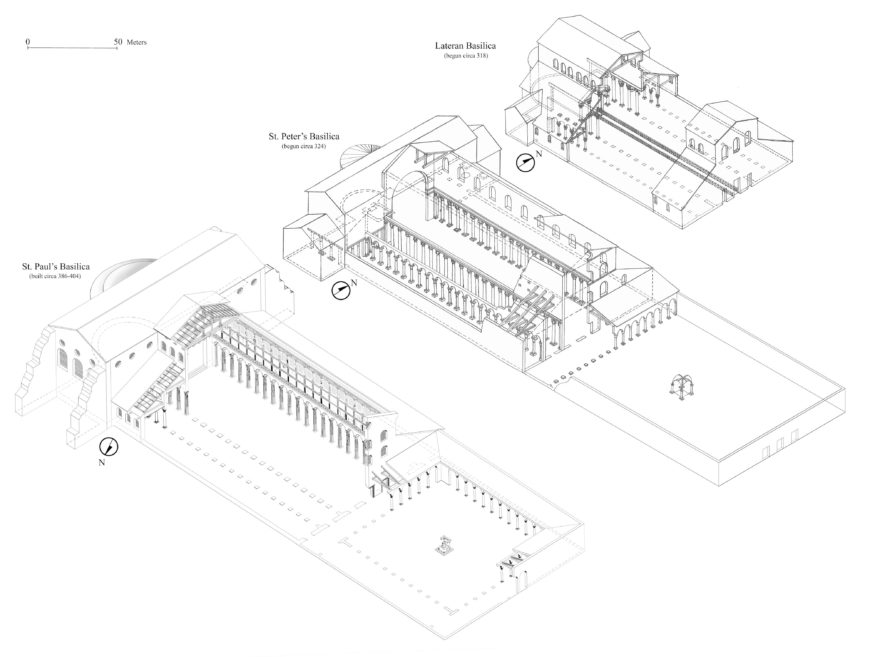

Comparative view of the Constantinian basilicas of St. Peter and at the Lateran, alongside the Theodosian basilica of St. Paul. All are depicted at the same scale. Model of St. Paul’s by Evan Gallitelli. Image by Evan Gallitelli includes drawings by Konstantin Brandenburg published in Hugo Brandenburg’s Ancient Churches of Rome from the Fourth to the Seventh Century (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), fig. 1. (© Nicola Camerlenghi)

Martyria and Mausolea

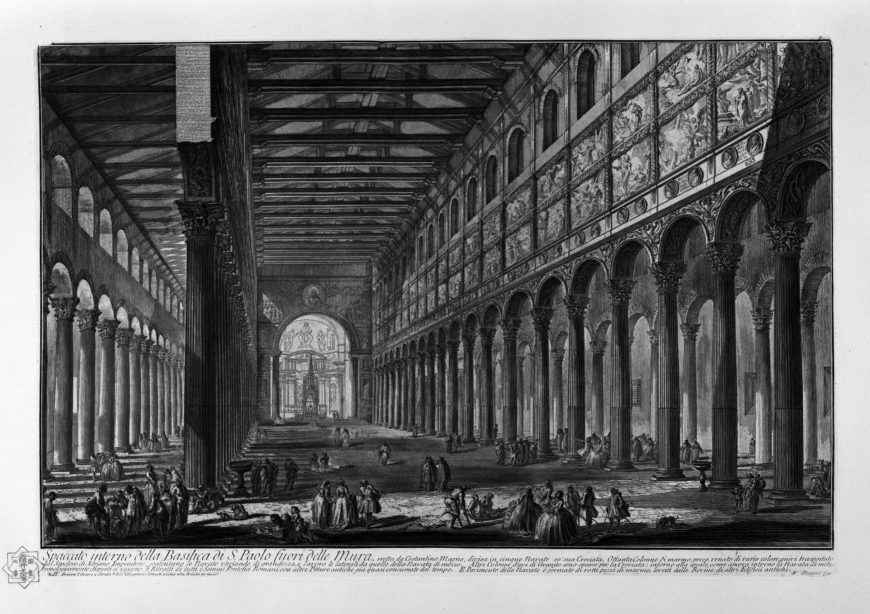

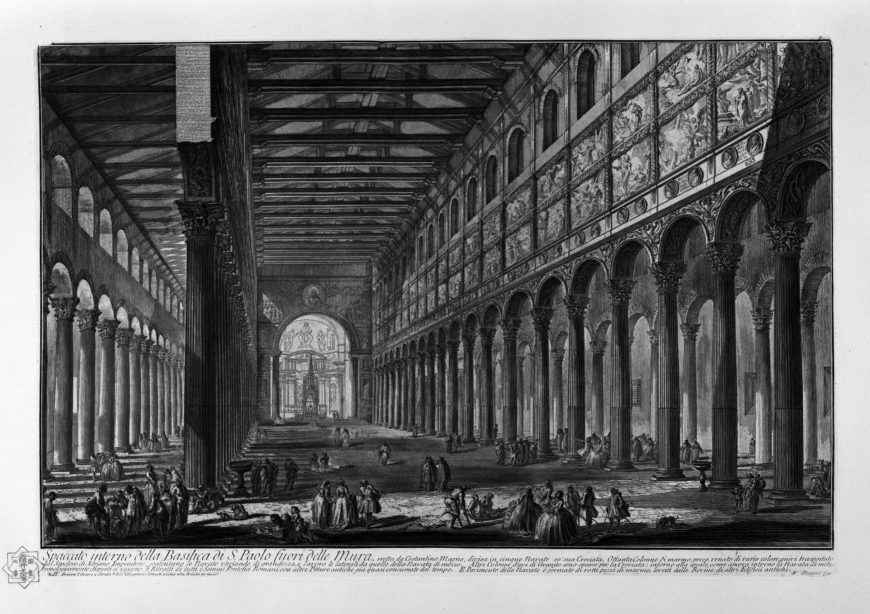

Although the church gradually eliminated the great funeral banquets at the graves of martyrs, the cult of martyrs was manifest in other ways, notably the importance of pilgrimage and the dissemination of relics. In spite of this, there was not a standard architectural form for the martyria, which instead seem to depend on site-specific conditions or regional developments. In Rome, for example, S. Paolo fuori le mura (St. Paul Outside the Walls), begun 384, follows the model of St. Peter’s in adding a transept to a huge five-aisled basilica.

St. Paul’s fuori le mura (interior looking east before destruction), begun 384, Rome (etching by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 18th century)

St. Demetrios in his tomb, reliquary pendant, 11th century, gold and enamel, 3.7 x 4.6 x 1 cm (The British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

At Thessaloniki, the basilica of H. Demetrios (late fifth century) incorporated the remains of a crypt and other structures associated with the Roman bath where Demetrius was martyred.

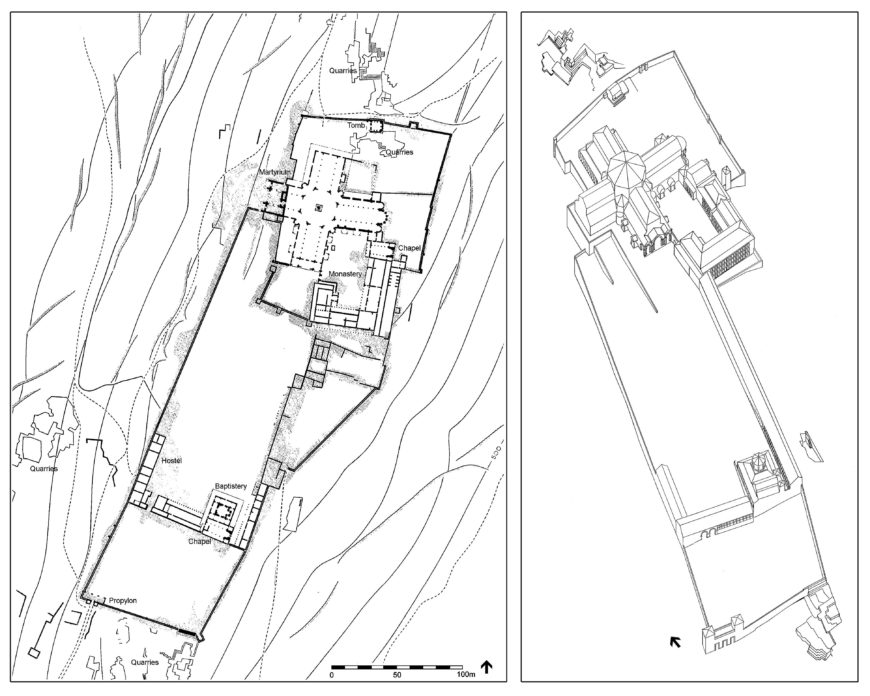

At rural locations, large complexes emerged, as at Qal’at Sem’an, built c. 480–90 in Syria, which had four basilicas radiating from an octagonal core, where the stylite saint’s column stood.

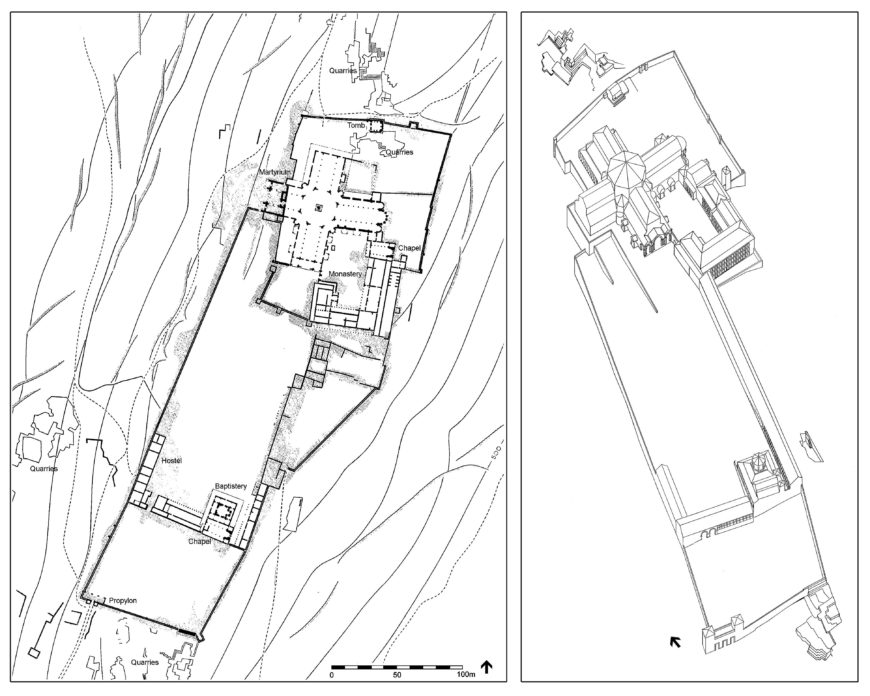

Plan and reconstruction of Qal’at Sem’an, (© Robert G. Ousterhout)

An entire city (Abu Mena), with church architecture of increasing complexity, grew around the venerated tomb of St. Menas in Egypt.

At Hierapolis in Asia Minor, a large octagonal complex was built at the site of the tomb of St. Philip (view plan).

At Ephesus, a cruciform church arose at the tomb of St. John the Evangelist.

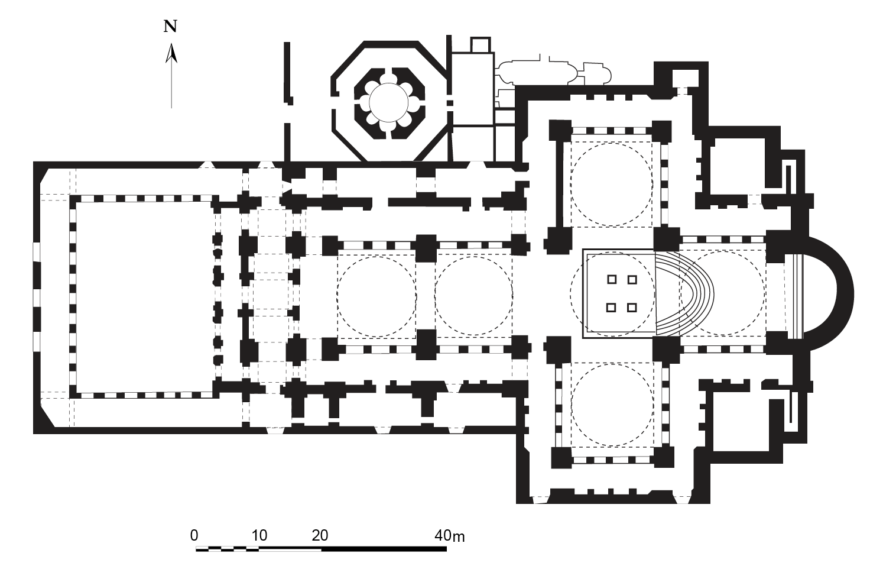

Reconstructed plan, church of St. John the Evangelist, Ephesus (Marsyas, CC BY 3.0)

Others were simpler in form. At the martyrium of St. Thekla at Meryemlik, c. 480, a three-aisled basilica was added above her holy cave. At Sinai, the sixth-century basilica was augmented by subsidiary chapels along its sides, but the holy site—the Burning Bush—lay outside, immediately to the east of its apse (view plan).

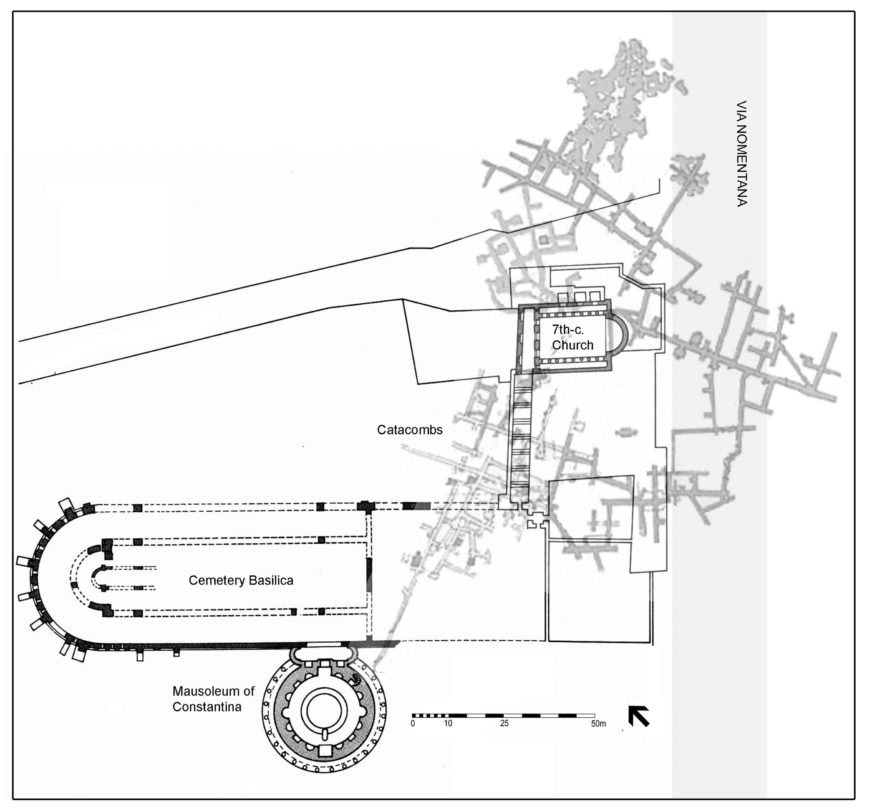

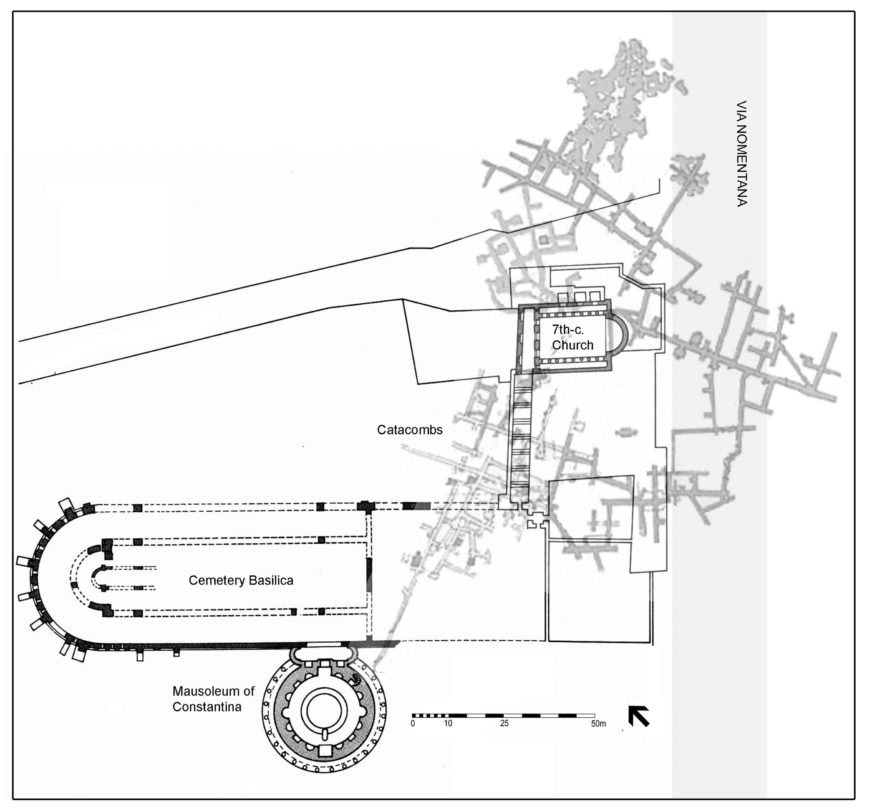

Rome, Sant’Agnese site plan: cemetery basilica with attached Mausoleum of Constantina (S. Costanza); medieval Basilica of Sant’Agnese above the catacombs (in gray) (© Robert Ousterhout)

The desire for privileged burial perpetuated the tradition of Late Antique mausolea, which were often octagonal or centrally planned. In Rome the fourth-century mausolea of Helena and Constantina were attached to cemetery basilicas.

Cruciform chapels seem to be a new creation, with a shape that derived its meaning from the life-giving Cross, a relationship emphasized in the well-preserved Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, built c. 425, in Ravenna, which was originally attached to a cruciform church dedicated to S. Croce.

In Constantinople, the successors of Constantine were buried in the rotunda at the church of the Holy Apostles or its dependencies.

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna, c. 425 (photo: Evan Freeman, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Monasticism

Red Monastery, Sohag, early 6th century (photo: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Monasticism began to play an increasingly important role in society, but from the perspective of architecture, early monasteries lacked systematic planning and were dependent on site-specific conditions. The coenobitical system (communal monasticism) included living quarters, with cells for the monks, as well as a refectory for common dining and a church or chapel for common worship. Evidence is preserved in the desert communities of Egypt and Palestine. At the Red Monastery at Sohag, the formal spaces are contained within a fortress-like complex, although it is unclear where with or without the enclosure the monks actually lived. In the Judean Desert, a variety of hermits’ cells are preserved – simple caves carved into the rough landscape.

Red Monastery, Sohag, early 6th century (photo: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Urban Planning

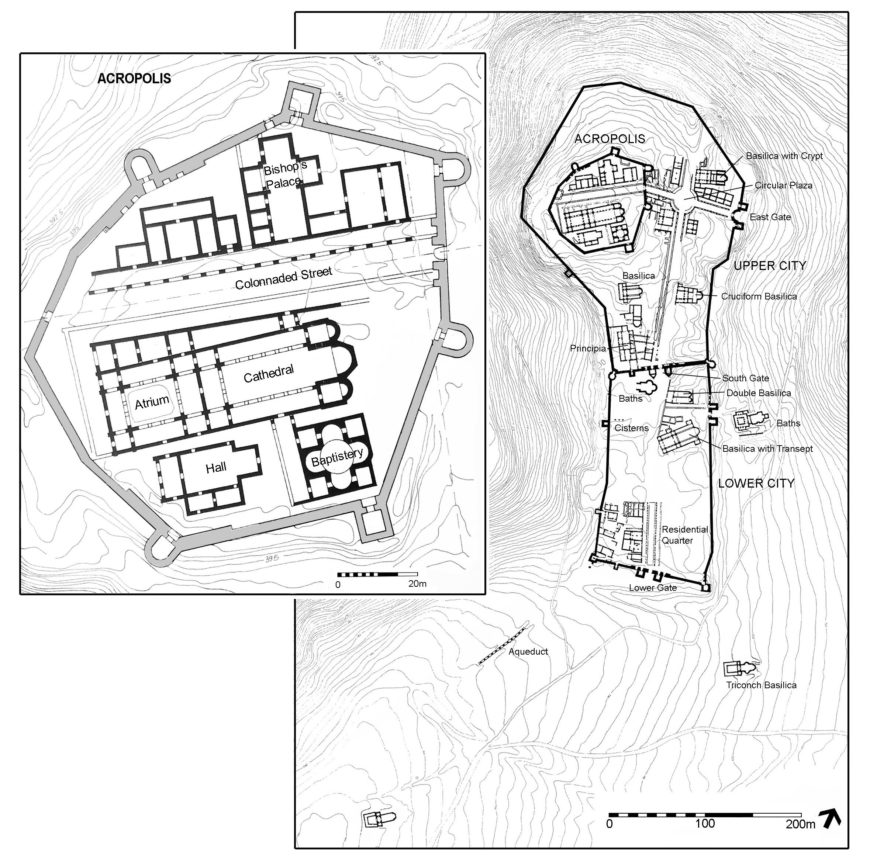

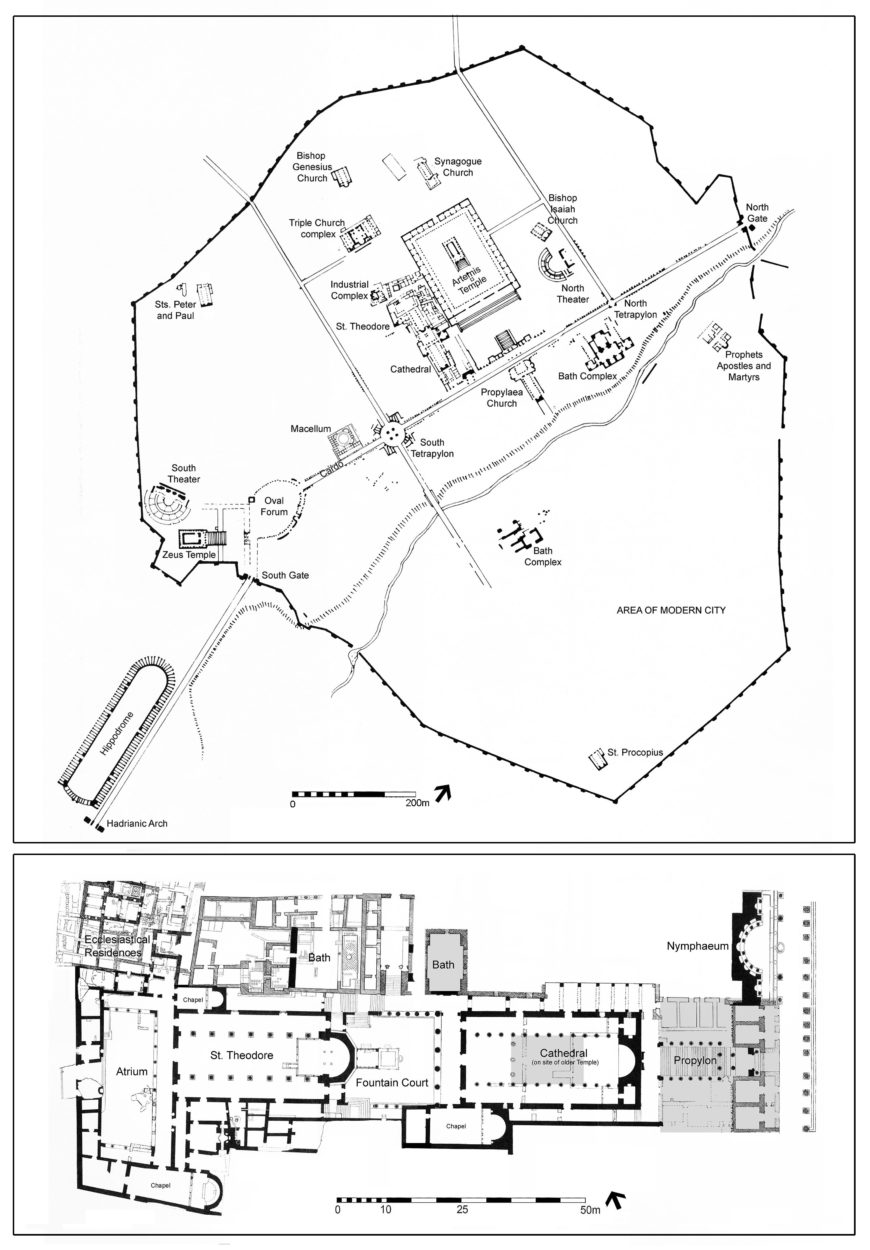

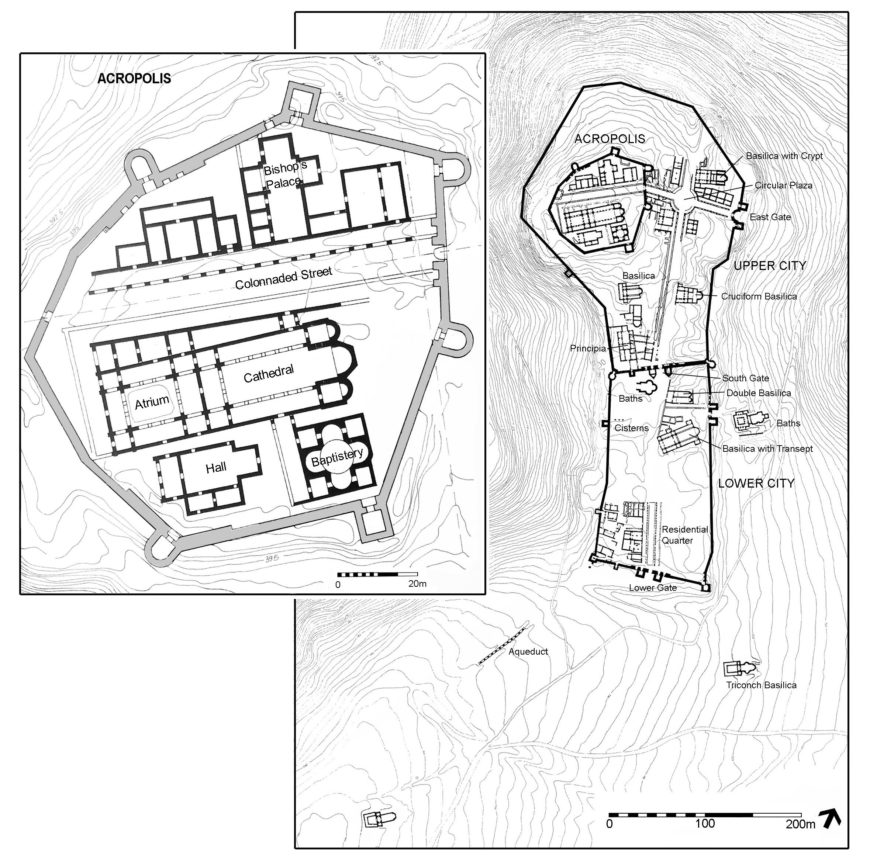

In general, urban planning in this period follows Roman and Hellenistic models, as Justinian’s new city of Iustiniana Prima (Caracin Grad, in modern Serbia) amply demonstrates.

Caričin Grad (Iustiniana Prima) site plan, with detail of the acropolis (© Robert Ousterhout)

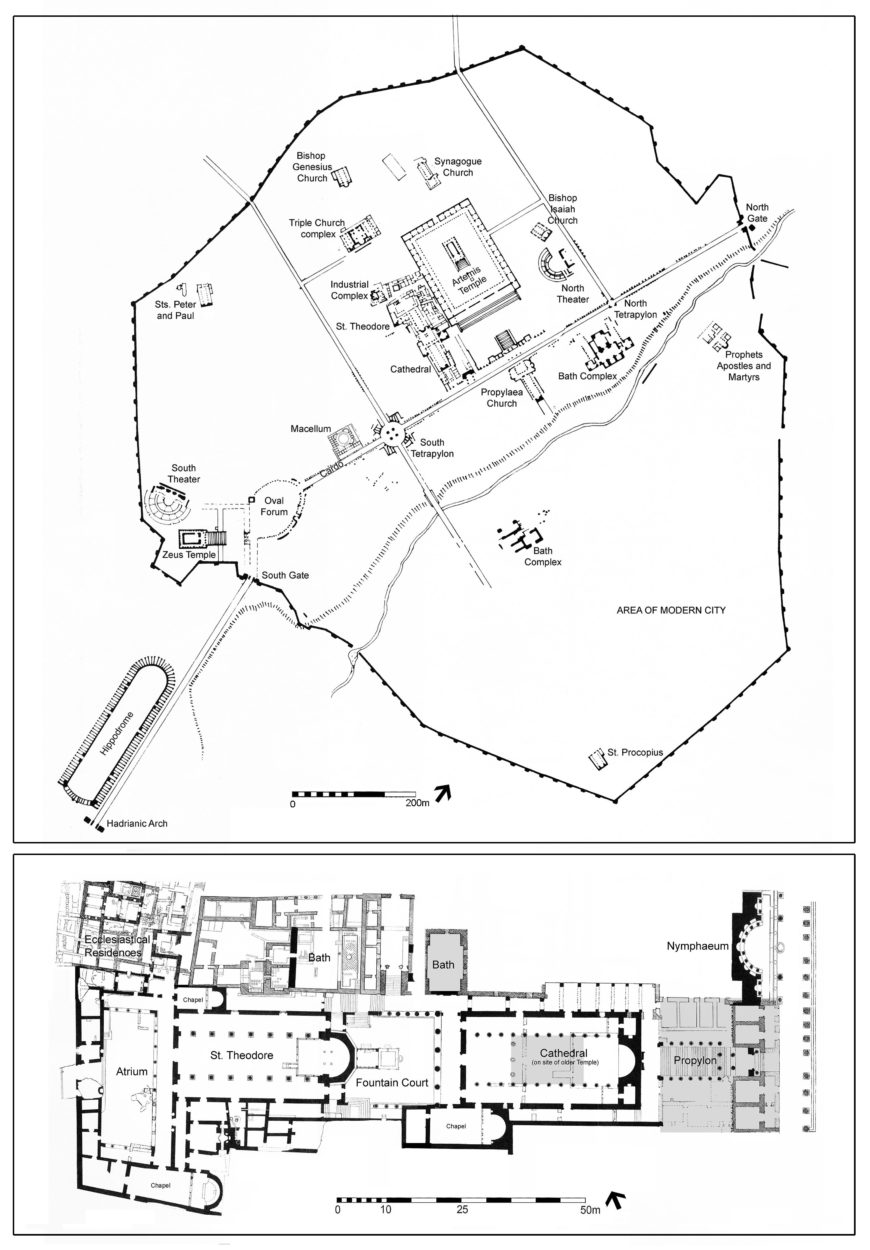

Gerasa (Jerash), plan of the city with a detail of the Cathedral complex (© Robert Ousterhout)

At Gerasa (in modern Jordan), Thessaloniki, and elsewhere, existing city plans were reconfigured to give prominence to the new Christian structures.

In Jerusalem and Athens, there may have been an intentional visual juxtaposition of the new Christian cathedral with the abandoned Jewish or pagan temple.

While the Theodosian Code legislated the cessation of pagan worship, it recommended the preservation of the temple building and its contents because of their artistic value. The transformation of temples into churches was rare before the sixth century.

Defensive architecture followed Roman practices.

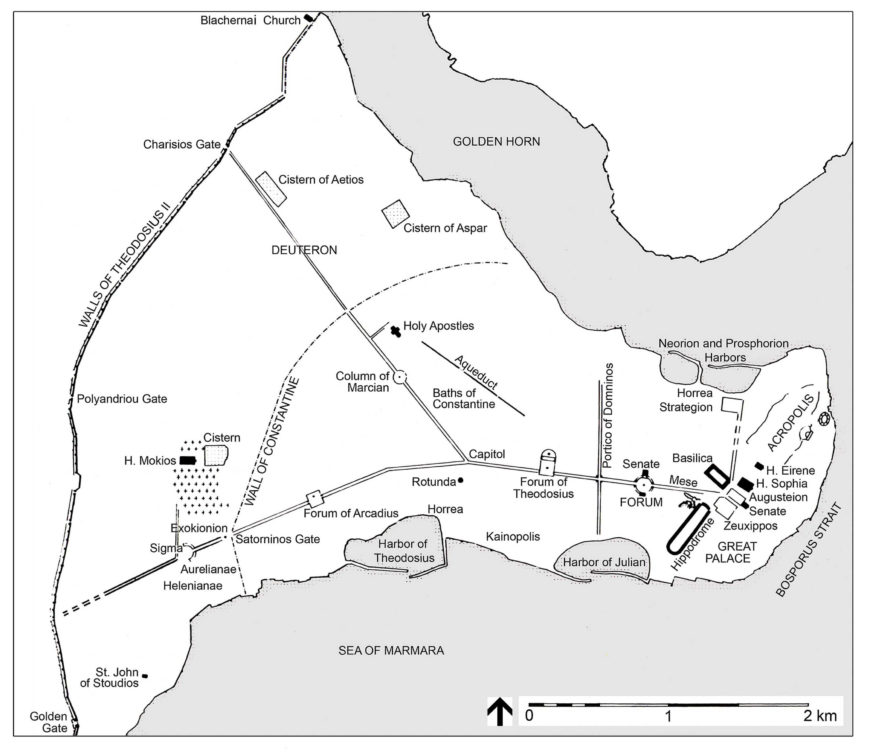

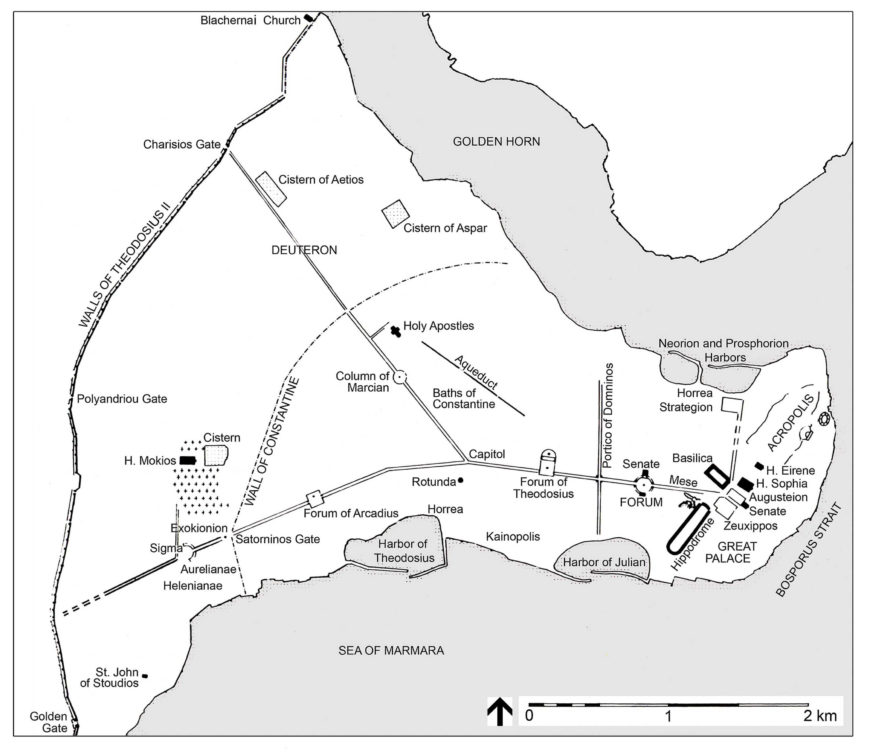

Constantinople, plan of the fifth century city (© Robert G. Ousterhout, based on Cyril Mango, Développement urbaine de Constantinople, 1985)

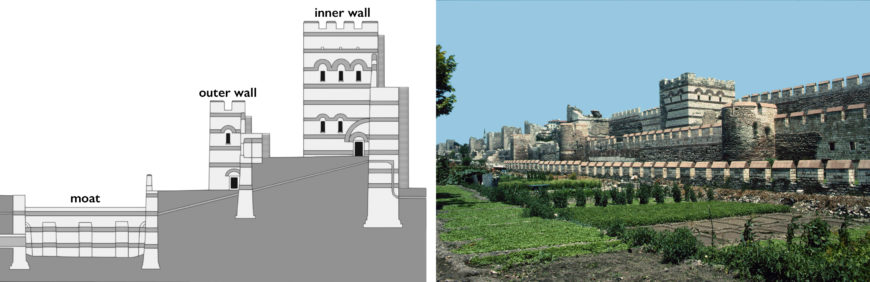

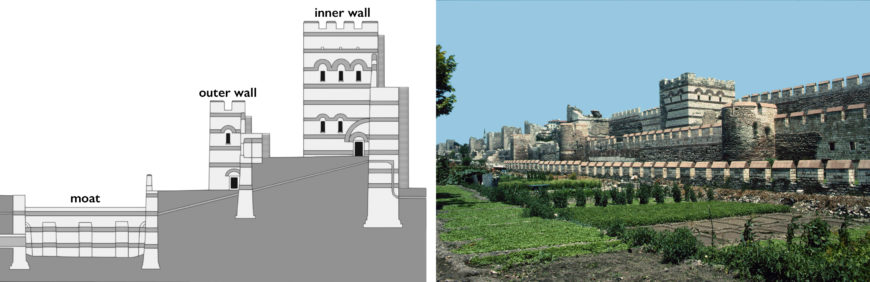

The walls of Constantinople, added by Theodosius II (412–13) stand as a singular achievement, combining two lines of defensive walls with a moat. In a like manner, the system of aqueducts and cisterns at Constantinople expanded upon established Roman technology to create the most extensive water system in Antiquity.

Left: diagram of the Theodosian walls, Constantinople (adapted from Glz19, CC BY-SA 4.0); right: partially restored Theodosian walls with garden plots in the moat, Constantinople (Istanbul), 412–413 (photo: © Robert G. Ousterhout)

Domestic Architecture

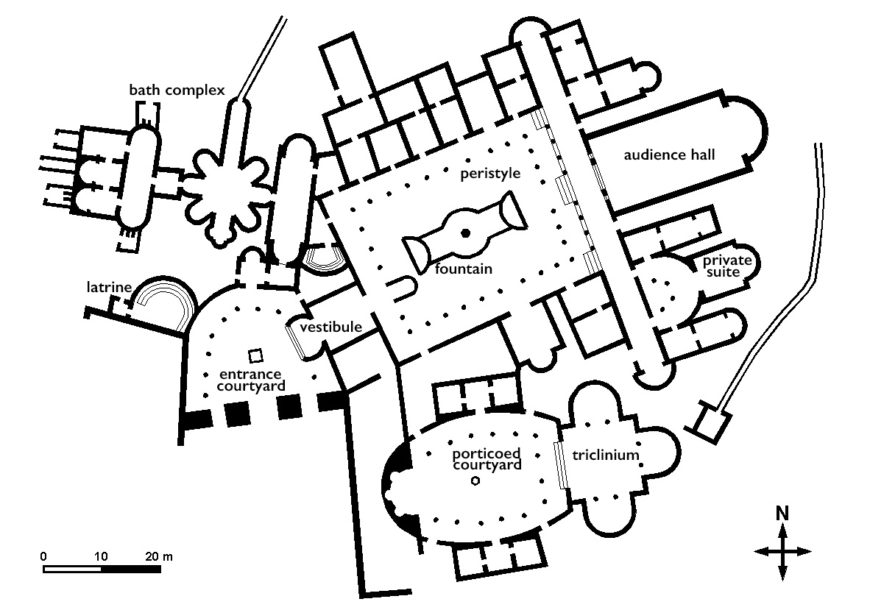

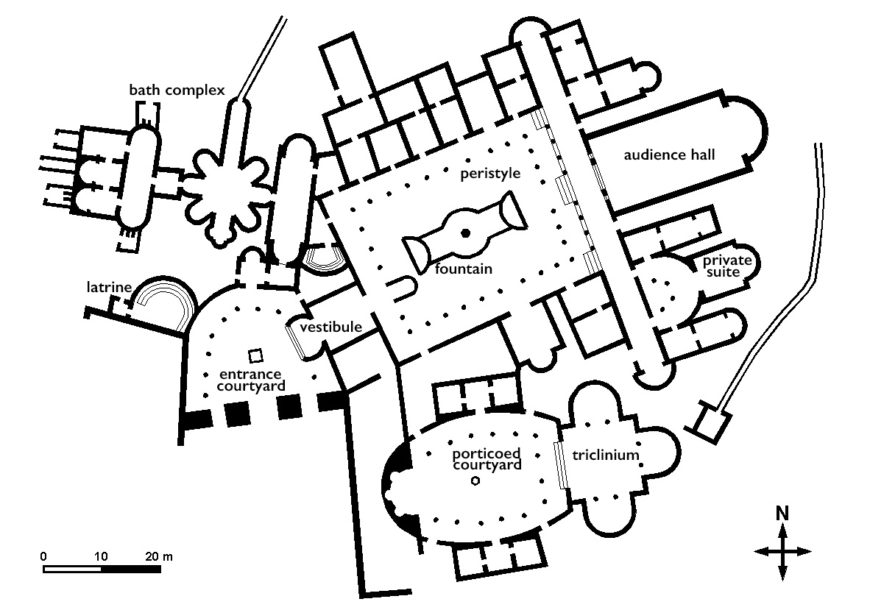

Plan of villa, Piazza Armerina (adapted from plan by Bjs, CC0)

Standard planning continued in domestic architecture as well. Large houses excavated in Asia Minor (Sardis, Ephesus), North Africa (Carthage, Spaitla, Apollonia), Italy (Ravenna, Piazza Armerina), Greece (Athens, Argos), and elsewhere include porticoed gardens, audience halls, and triclinia (dining rooms). The Great Palace in Constantinople and the so-called Palace of Theodoric in Ravenna were essentially elaborations on or repetitions of the Late Roman villa. Perhaps the most significant changes in the Late Antique domus (house) were the increasing size and number of ceremonial spaces (audience halls and triclinia)—as at the early fourth century villa at Piazza Armerina (in Sicily)—and the incorporation of chapels into the domestic setting—as at the Palace of the Dux at Apollonia (in modern Libya). The latter phenomenon is indicative of the growing importance of private worship and was a source of growing concern in ecclesiastical legislation. With significant economic and social changes, however, by the end of the period under discussion, the domus disappeared.

Additional Resources

Smarthistory’s free Guide to Byzantine Art e-book

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)

Cite this page as: Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout, “Early Byzantine architecture after Constantine,” in Smarthistory, June 8, 2020, accessed May 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/early-byzantine-architecture-after-constantine/.

Architecture in the Age of Justinian

Periods of Byzantine history

Early Byzantine (including Iconoclasm) c. 330 – 843

Middle Byzantine c. 843 – 1204

The Fourth Crusade & Latin Empire 1204 – 1261

Late Byzantine 1261 – 1453

Post-Byzantine after 1453

Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul), 532-37 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Plan of church of the Theotokos, c. 484, Mt. Gerizim (in modern Israel) (adapted from Schneider)

New trends

Although standardized church basilicas continued to be constructed, by the end of the fifth century, two important trends emerge in church architecture: the centralized plan, into which a longitudinal axis is introduced, and the longitudinal plan, into which a centralizing element is introduced.

The first type may be represented by the ruined church of the Theotokos on Mt. Gerizim (in modern Israel), c. 484, which has a developed sanctuary bay projecting beyond an aisled octagon with radiating chapels; the second by the so-called Domed Basilica at Meriamlik (on the southern coast of Turkey), c. 471-94, which superimposed a dome on a standard basilican nave (view plan). Both may be attributed to the patronage of emperor Zeno.

Sts. Sergius and Bacchus (Küçük Ayasofya Camii), Constantinople (Istanbul), completed before 536 (photo: © Robert G. Ousterhout)

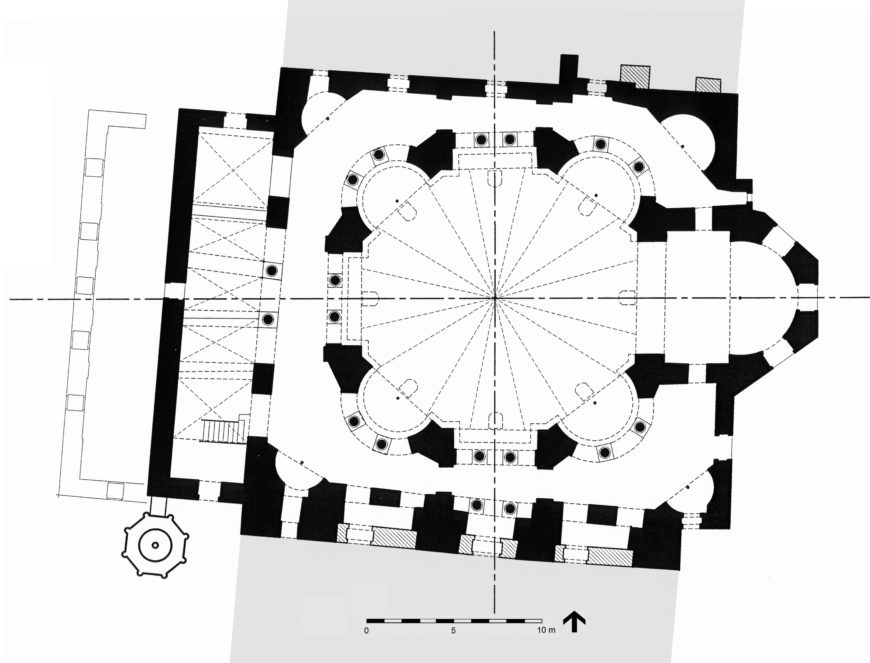

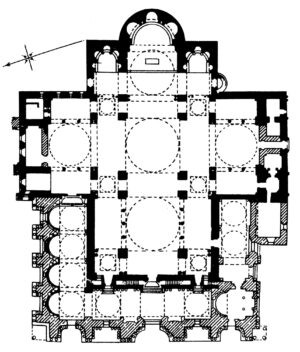

Plan of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus (Küçük Ayasofya Camii), Constantinople (Istanbul), completed before 536 (© Robert G. Ousterhout, redrawn after J. Ebersolt and A. Thiers, Les Églises de Constantinople, 1913)

Section of San Vitale, Ravenna, from James Fergusson, The Illustrated Handbook of Architecture, vol. 2 (London: John Murray, 1855), 513

The reign of Justinian

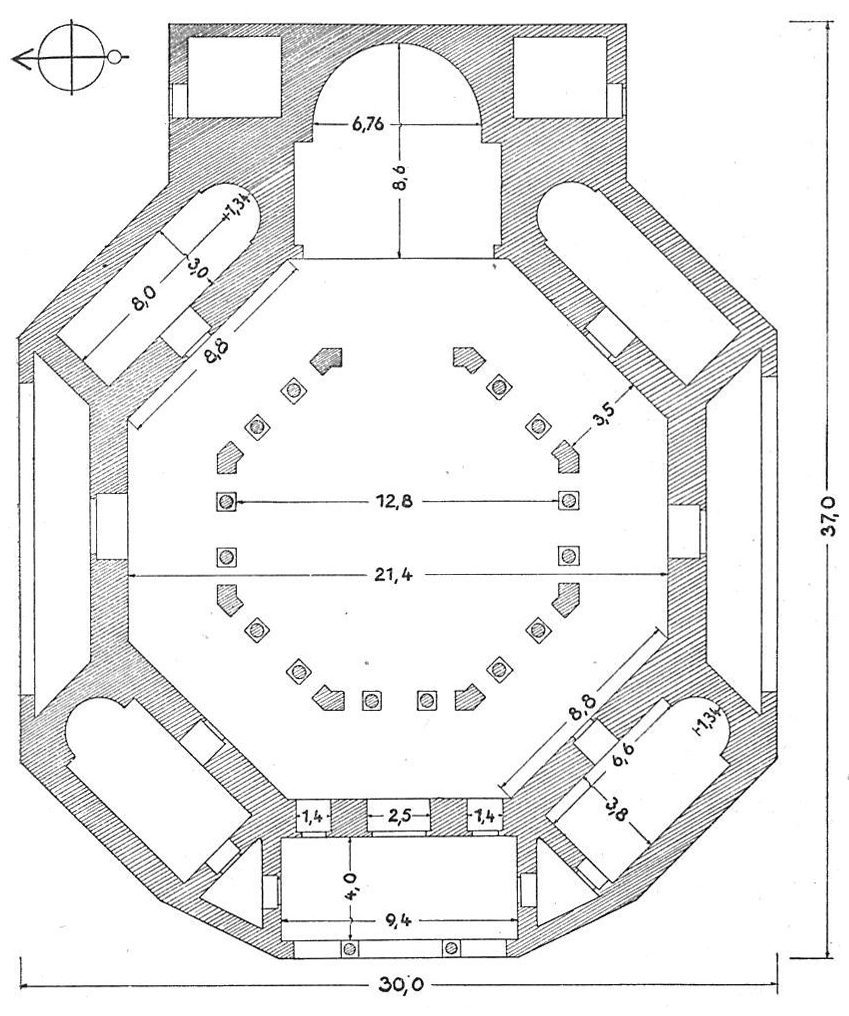

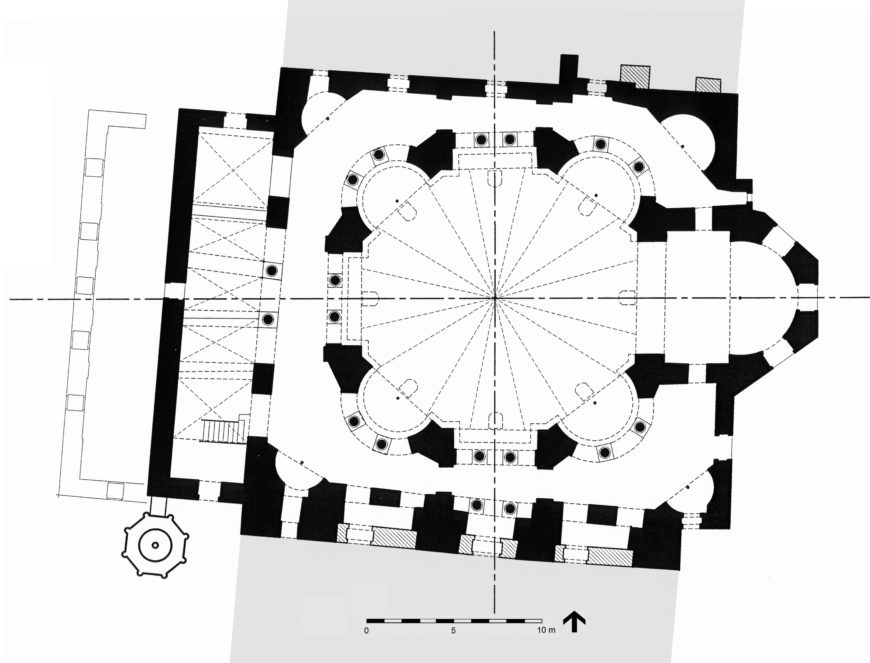

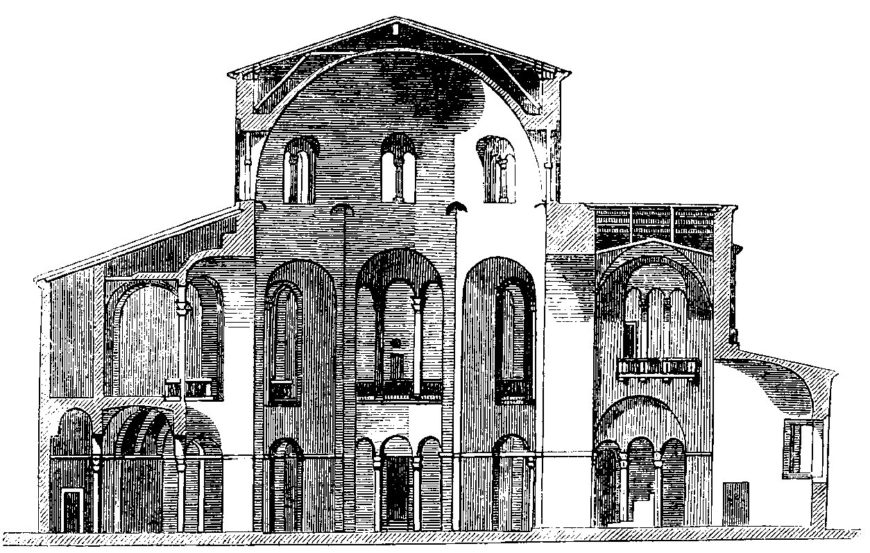

Both trends are further developed during the reign of Justinian (reigned 527 to 565). HH. Sergios and Bakchos in Constantinople, completed before 536, and S. Vitale in Ravenna, completed c. 546/48, for example, are double-shelled octagons (view plan of San Vitale) of increasing geometric sophistication, with masonry domes covering their central spaces, perhaps originally combined with wooden roofs for the side aisles and galleries.

San Vitale, c. 546/48, Ravenna (photo: Evan Freeman, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

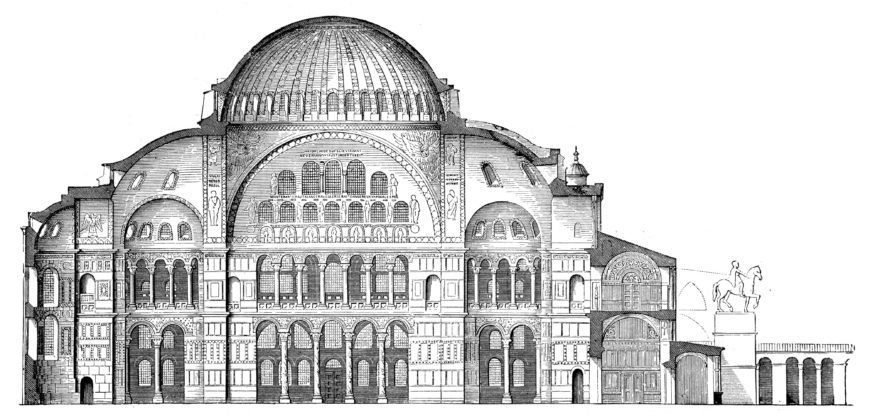

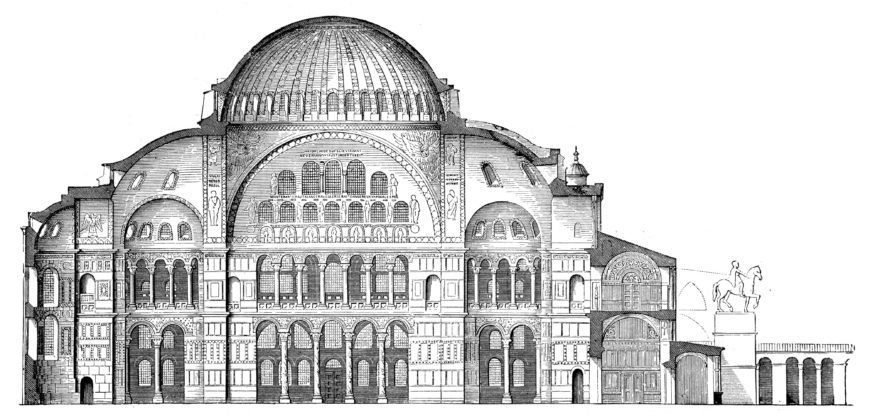

Section of Hagia Sophia by Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Istanbul, 532-37, from Wilhelm Lübke / Max Semrau: Grundriß der Kunstgeschichte. 14. Auflage. Paul Neff Verlag, Esslingen, 1908 (view annotated section)

Hagia Sophia, Constantinople

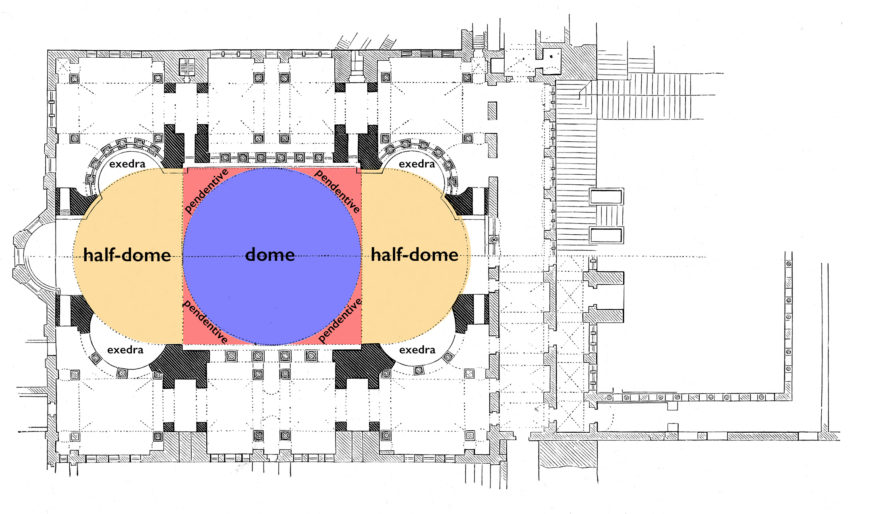

Several monumental basilicas of the period included domes and vaulting throughout, most notably at Hagia Sophia, built 532-37 by the mechanikoi Anthemios and Isidoros, which combines elements of the central plan and the basilica on an unprecedented scale.

Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul), 532-37 (photo: © Robert G. Ousterhout) (view annotated photo)

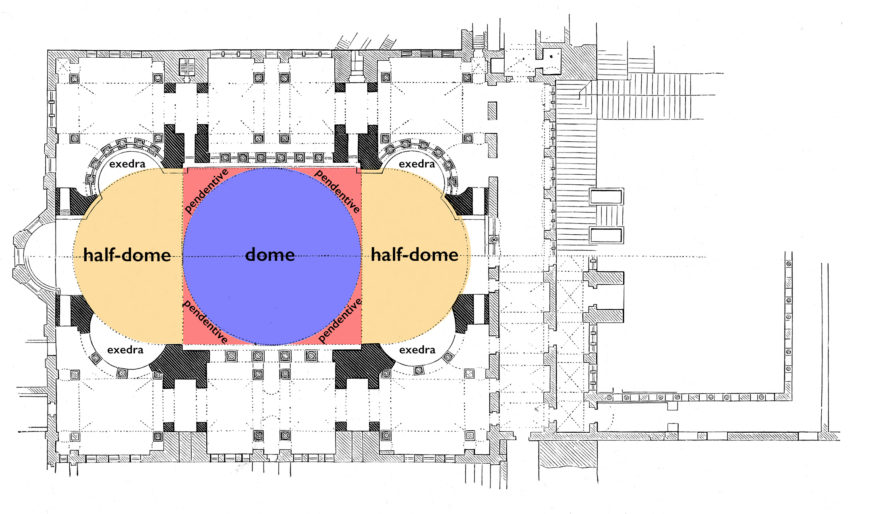

Its unique design focused on a daring central dome of slightly more than 100 feet in diameter, raised above pendentives, and braced to the east and west by half-domes. The aisles and galleries are screened by colonnades (rows of columns), with exedrae (semicircular recesses) at the corners. Following the innovative trends in Late Roman architecture, the structural system concentrates the loads at critical points, opening the walls with large windows.

Floor plan of Hagia Sophia by Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Constantinople (Istanbul), 532-37, based on a diagram from Wilhelm Lübke / Max Semrau: Grundriß der Kunstgeschichte. 14. Auflage. Paul Neff Verlag, Esslingen, 1908.

With glistening marble revetments on all flat surfaces and more than seven acres of gold mosaic on the vaults, the effect was magical—whether in daylight or by candlelight, with the dome seeming to float aloft with no discernable means of support; accordingly Procopios writes that the interior impression was “altogether terrifying.”

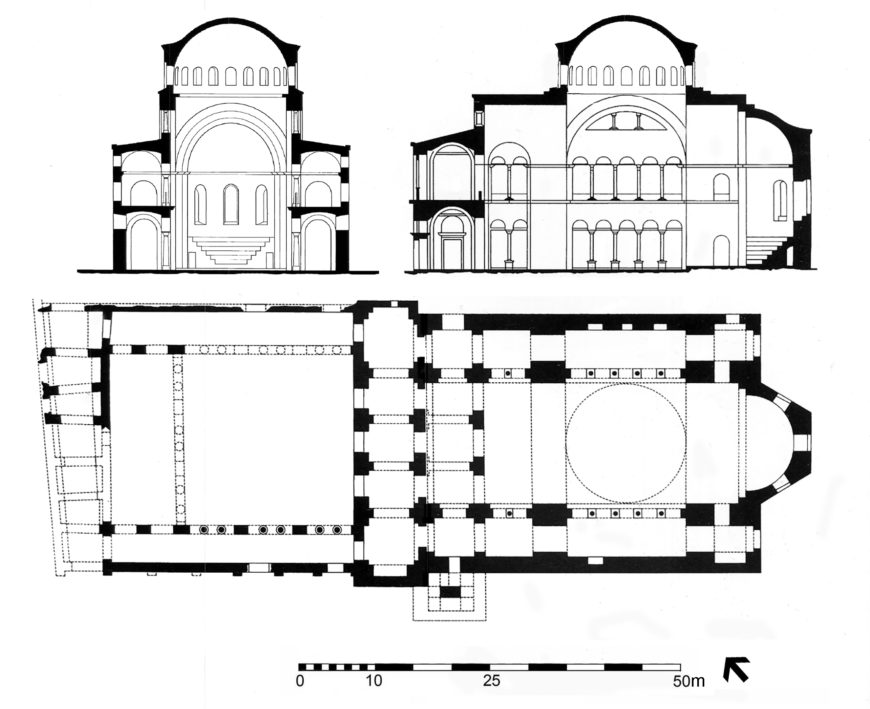

H. Eirene, Constantinople

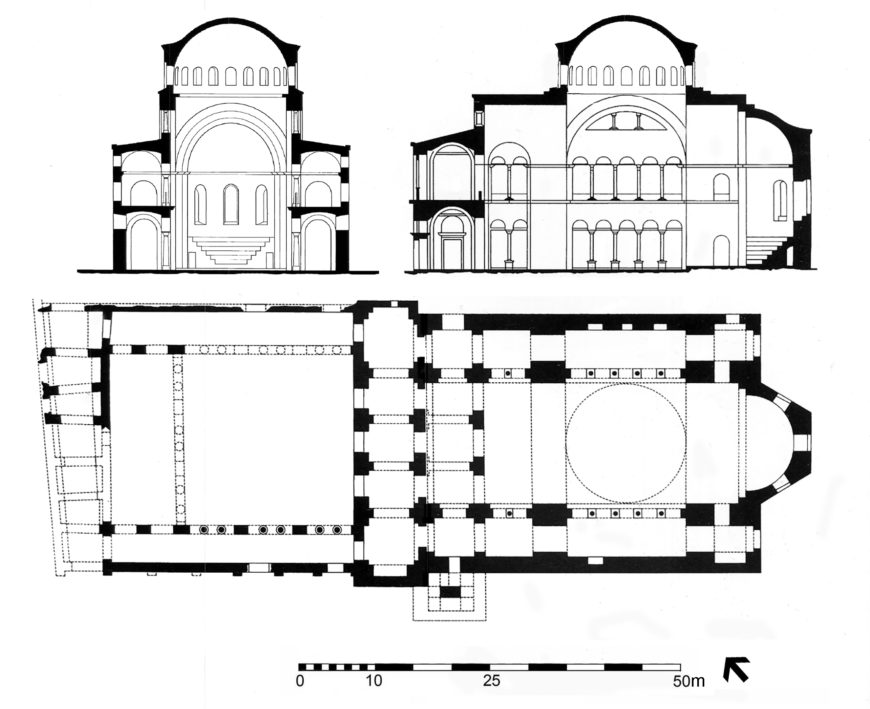

Related to H. Sophia are the domed basilicas of H. Eirene in Constantinople, begun 532, and ruined Basilica ‘B’ in Philippi (Greece), built before 540, each with distinctive elements to its design. The common feature in all three buildings was an elongated nave, partially covered by a dome on pendentives, but lacking necessary lateral buttressing. All three buildings suffered partial or complete collapse in subsequent earthquakes. Read about the redesign of H. Eirene after its collapse.

Hagia Eirene, Constantinople (Istanbul), plan and hypothetical sections of the sixth-century building (© Robert G. Ousterhout, adapted from S. Ćurčić, Architecture in the Balkans, 2010)

Hagia Sophia’s new dome

At H. Sophia, textual accounts suggest that the first dome, which fell in 557, was a structurally daring, shallow pendentive dome, in which the curvature continued from the pendentives, but with a ring of windows at its base.

Dome of Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (photo: © Robert G. Ousterhout)

A more stable, hemispherical dome replaced the original—essentially that which survives today, with partial collapses and repairs in the west and east quadrants in the tenth and fourteenth centuries.

Although H. Polyeuktos, built in Constantinople by Justinian’s rival Juliana Anicia, is normally reconstructed as a domed basilica—and thus suggested to be the forerunner of H. Sophia—it was unlikely domed, although it was certainly its predecessor in lavishness.

Reconstructed floor plan, church of St. John the Evangelist, Ephesus, drawn after Clive Foss, Ephesus after Antiquity: A late antique, Byzantine and Turkish City (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1979. (Cordanrad, CC BY 3.0)

Plan, San Marco, Venice, from Fletcher, A History of Architecture (1905)

Five-domed churches

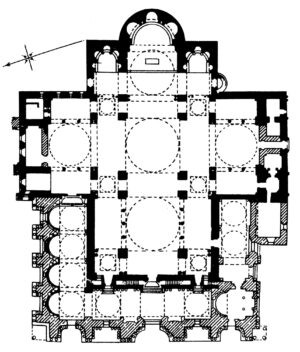

The spatial unit formed by the dome on pendentives could also be used as a design module, as at Justinian’s rebuilding of the church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, in which five domes covered the cruciform building.

A similar design was employed in the rebuilding of St. John’s basilica at Ephesus, completed before 565, which because of its elongated nave took on a six-domed design.

The late eleventh-century S. Marco in Venice follows this sixth-century scheme.

Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai (Library of Congress)

The enduring basilica

In spite of design innovations, traditional architecture continued in the sixth century with the wooden roofed basilica continuing as the standard church type.

At St. Catherine’s at Mt. Sinai, built c. 540, the church preserves its wooden roof and much of its decoration. The three-aisled plan incorporated numerous subsidiary chapels flanking the aisles.

At the sixth-century Cathedral of Caricin Grad, the three-aisled basilica included a vaulted sanctuary area, with the earliest securely dated example of pastophoria: apsed chapels—known as the prothesis and diakonikon—which flanked the central altar area to form a tripartite sanctuary. This tripartite form that would become standard in later centuries.

Hagia Sophia, Thessaloniki (photo: © Robert G. Ousterhout)

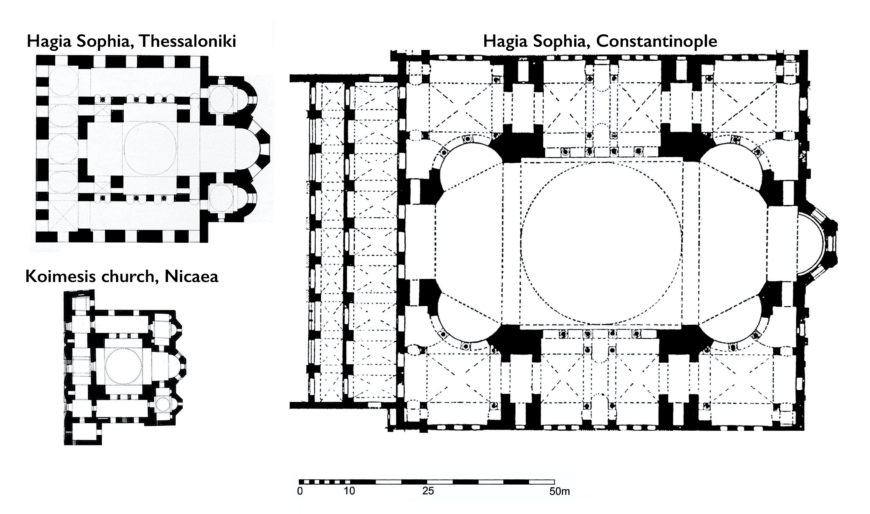

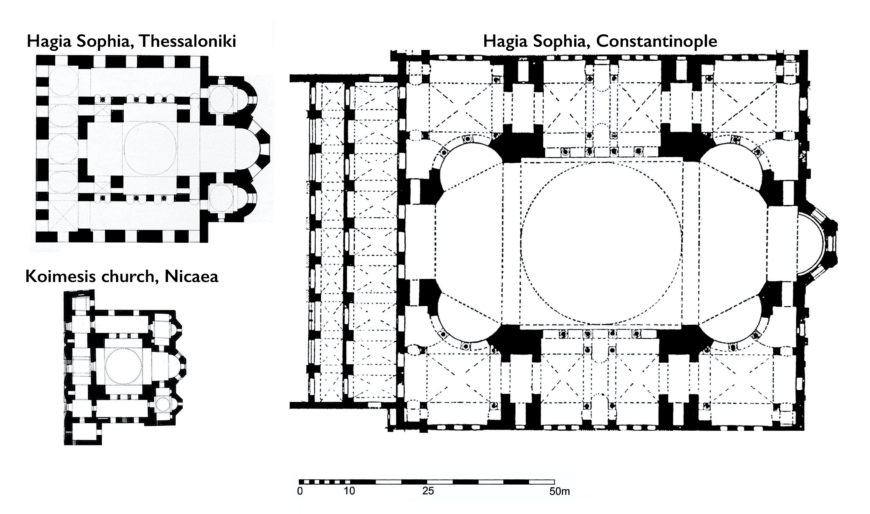

Plans drawn to the same scale, H. Sophia in Constantinople, H. Sophia in Thessaloniki, and the Koimesis church in Nicaea (© Robert G. Ousterhout)

Justinian’s legacy

Church types of the subsequent period tend to follow in simplified form the grand developments of the age of Justinian. H. Sophia in Thessalonikie for example, built less than a century later than its namesake, is both considerably smaller and heavier, as is the Koimesis church at Nicaea.

Both correct the basic problems in the structural design by including broad arches to brace the dome on all four sides.

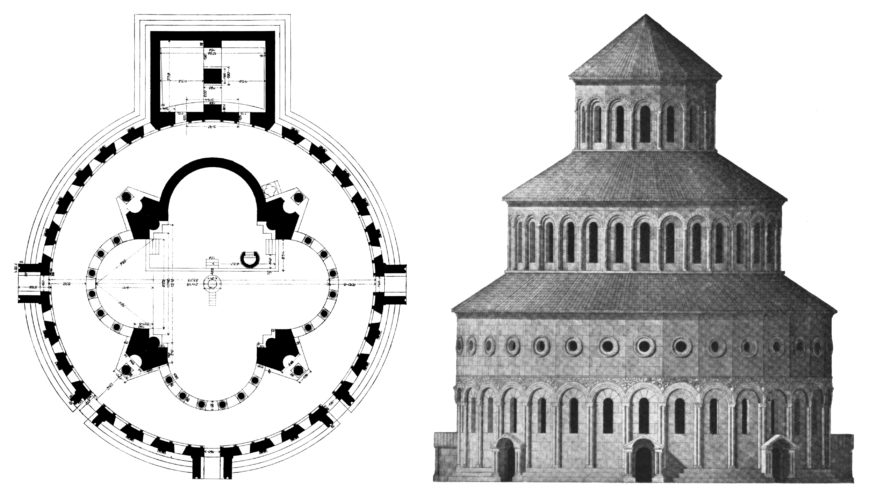

The Caucasus

In the Caucasus, Georgia and Armenia witness a flourishing of architecture in the seventh century, with numerous, distinctive, centrally planned, domed buildings, constructed of rubble faced with a fine ashlar, although their relationship with Byzantine architectural developments remains to be clarified.

Left: exterior view of the church of St. Hripsime, Vagarshapat, 618 (photo: Rita Willaert, CC BY 2.0); Right: interior view of St. Hripsime (photo: Andrea Kirkby, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The domed church of St. Hripsime at Vagarshapat has a dome rising above eight supports, set within a rectangular building.

Church of the Cross, 586–604, Jvari (Mtskheta, Georgia) (photo: Mamuka Gotsridze, CC BY-SA 4.0)

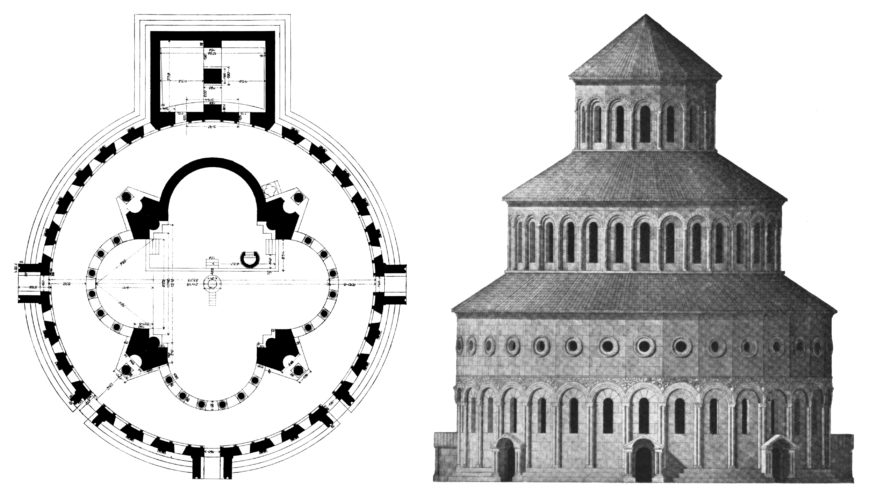

The church at Church of the Cross at Jvari (Mtskheta) is similar, but with its lateral apses projecting. The aisled tetraconch church of Zvartnots stands out as following Byzantine, particularly Syrian, models.

Church of the Vigilant Powers (Zvart‘nots‘), Vagarshapat, plan and possible reconstructed elevations, from Josef Strzygowski, Die Baukunst der Armenier und Europa, vol. 1 (Vienna: A. Schroll & Co., 1918), figs. 112 and 119.

Cite this page as: Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout, “Innovative architecture in the age of Justinian,” in Smarthistory, June 8, 2020, accessed May 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/innovative-architecture-in-the-age-of-justinian/.

Hagia Sophia

Constantine the Great presents the city (Constantinople) and Justinian the Great presents Hagia Sophia to the Virgin, mosaic, probably 10th Century, Southwestern Entrance, Hagia Sophia (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A symbol of Byzantium

The great church of the Byzantine capital Constantinople (Istanbul) took its current structural form under the direction of the Emperor Justinian I. The church was dedicated in 537, amid great ceremony and the pride of the emperor (who was sometimes said to have seen the completed building in a dream). The daring engineering feats of the building are well known. Numerous medieval travelers praise the size and embellishment of the church. Tales abound of miracles associated with the church. Hagia Sophia is the symbol of Byzantium in the same way that the Parthenon embodies Classical Greece or the Eiffel Tower typifies Paris.

Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, 532–37 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Each of those structures express values and beliefs: perfect proportion, industrial confidence, a unique spirituality. By overall impression and attention to detail, the builders of Hagia Sophia left the world a mystical building. The fabric of the building denies that it can stand by its construction alone. Hagia Sophia’s being seems to cry out for an other-worldly explanation of why it stands because much within the building seems dematerialized, an impression that must have been very real in the perception of the medieval faithful. The dematerialization can be seen in as small a detail as a column capital or in the building’s dominant feature, its dome.

Basket Capital, Hagia Sophia (photo: William Allen, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Let us start with a look at a column capital

The capital is a derivative of the Classical Ionic order via the variations of the Roman composite capital and Byzantine invention. Shrunken volutes appear at the corners decorative detailing runs the circuit of lower regions of the capital. The column capital does important work, providing transition from what it supports to the round column beneath. What we see here is decoration that makes the capital appear light, even insubstantial. The whole appears more as filigree work than as robust stone capable of supporting enormous weight to the column.

Ionic Capital, North Porch of the Erechtheion (Erechtheum), Acropolis, Athens, marble, 421–407 B.C.E., British Museum (photo: Steven Zucker CC:BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Compare the Hagia Sophia capital with a Classical Greek Ionic capital, this one from the Greek Erechtheum on the Acropolis, Athens. The capital has abundant decoration but the treatment does not diminish the work performed by the capital. The lines between the two spirals dip, suggesting the weight carried while the spirals seem to show a pent-up energy that pushes the capital up to meet the entablature, the weight it holds. The capital is a working member and its design expresses the working in an elegant way.

Left: Basket Capital, Hagia Sophia (photo: William Allen, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Ionic Capital, North Porch of the Erechtheion (Erechtheum), Acropolis, Athens, marble, 421–407 B.C.E., British Museum (photo: Steven Zucker CC:BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The relationship between the two is similar to the evolution of the antique to the medieval seen in the mosaics of San Vitale. A capital fragment on the grounds of Hagia Sophia illustrates the carving technique. The stone is deeply drilled, creating shadows behind the vegetative decoration. The capital surface appears thin. The capital contradicts its task rather than expressing it.

Deep Carving of Capital Fragment, Hagia Sophia (photo: William Allen, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This deep carving appears throughout Hagia Sophia’s capitals, spandrels, and entablatures. Everywhere we look stone visually denying its ability to do the work that it must do. The important point is that the decoration suggests that something other than sound building technique must be at work in holding up the building.

A golden dome suspended from heaven

We know that the faithful attributed the structural success of Hagia Sophia to divine intervention. Nothing is more illustrative of the attitude than descriptions of the dome of Hagia Sophia. Procopius, biographer of the Emperor Justinian and author of a book on the buildings of Justinian is the first to assert that the dome hovered over the building by divine intervention.

…the huge spherical dome [makes] the structure exceptionally beautiful. Yet it seems not to rest upon solid masonry, but to cover the space with its golden dome suspended from Heaven.from “The Buildings” by Procopius, Loeb Classical Library, 1940, online at the University of Chicago Penelope project

The description became part of the lore of the great church and is repeated again and again over the centuries. A look at the base of the dome helps explain the descriptions.

Hagia Sophia Dome, Semi-Dome and Cherubim in the pendentive (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The windows at the bottom of the dome are closely spaced, visually asserting that the base of the dome is insubstantial and hardly touching the building itself. The building planners did more than squeeze the windows together, they also lined the jambs or sides of the windows with gold mosaic. As light hits the gold it bounces around the openings and eats away at the structure and makes room for the imagination to see a floating dome.

Windows at the Base of the Dome, Hagia Sophia (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

It would be difficult not to accept the fabric as consciously constructed to present a building that is dematerialized by common constructional expectation. Perception outweighs clinical explanation. To the faithful of Constantinople and its visitors, the building used divine intervention to do what otherwise would appear to be impossible. Perception supplies its own explanation: the dome is suspended from heaven by an invisible chain.

Advice from an angel?

An old story about Hagia Sophia, a story that comes down in several versions, is a pointed explanation of the miracle of the church. So goes the story: A youngster was among the craftsmen doing the construction. Realizing a problem with continuing work, the crew left the church to seek help (some versions say they sought help from the Imperial Palace). The youngster was left to guard the tools while the workmen were away. A figure appeared inside the building and told the boy the solution to the problem and told the boy to go to the workmen with the solution. Reassuring the boy that he, the figure, would stay and guard the tools until the boy returned, the boy set off. The solution that the boy delivered was so ingenious that the assembled problem solvers realized that the mysterious figure was no ordinary man but a divine presence, likely an angel. The boy was sent away and was never allowed to return to the capital. Thus the divine presence had to remain inside the great church by virtue of his promise and presumably is still there. Any doubt about the steadfastness of Hagia Sophia could hardly stand in the face of the fact that a divine guardian watches over the church.*

Damage and repairs

Hagia Sophia sits astride an earthquake fault. The building was severely damaged by three quakes during its early history. Extensive repairs were required. Despite the repairs, one assumes that the city saw the survival of the church, amid city rubble, as yet another indication of divine guardianship of the church.

Extensive repair and restoration are ongoing in the modern period. We likely pride ourselves on the ability of modern engineering to compensate for daring 6th Century building technique. Both ages have their belief systems and we are understandably certain of the rightness of our modern approach to care of the great monument. But we must also know that we would be lesser if we did not contemplate with some admiration the structural belief system of the Byzantine Age.

*Helen C. Evans, Ph.D., “Byzantium Revisited: The Mosaics of Hagia Sophia in the Twentieth Century,” Fourth Annual Pallas Lecture (University of Michigan, 2006).

Historical outline: Isidore and Anthemius replaced the original 4th-century church commissioned by Emperor Constantine and a 5th-century structure that was destroyed during the Nika revolt of 532. The present Hagia Sophia or the Church of Holy Wisdom became a mosque in 1453 following the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans under Sultan Mehmed II. In 1934, Atatürk, founder of Modern Turkey, converted the mosque into a museum.

Cite this page as: Dr. William Allen, “Hagia Sophia, Istanbul,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed May 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/hagia-sophia-istanbul/.

Theotokos Mosaic, Hagia Sophia

Theotokos mosaic, 867, apse, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

Additional resources:

Natalia B. Teteriatnikov, Mosaics of Hagia Sophia, Istanbul: The Fossati Restoration and the Work of the Byzantine Institute (Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks) 1998.

Cite this page as: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “Theotokos mosaic, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul,” in Smarthistory, December 15, 2015, accessed May 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/theotokos-mosaic-hagia-sophia-istanbul/.

Church of San Vitale

Gold, glass, and marble dazzle the eye in this 6th-century church. High above us, Emperor Justinian presides.

San Vitale, begun c. 526–27, consecrated 547, Ravenna (Italy). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

San Vitale is one of the most important surviving examples of Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire architecture and mosaic work. It was begun in 526 or 527 under Ostrogothic rule. It was consecrated in 547 and completed soon after.

San Vitale, begun c. late 520s, consecrated 547, mosaics date between 546 and 556. The Church was restored 1540s, 1900, 1904, and in the 1930s, Ravenna, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

One of the most famous images of political authority from the “middle ages“ is the mosaic of the Emperor Justinian and his court in the sanctuary of the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. This image is an integral part of a much larger mosaic program in the chancel (the space around the altar).

Chancel with Justinian mosaic at lower left and apse mosaic at center, San Vitale, consecrated 547, Ravenna, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A major theme of this mosaic program is the authority of the emperor in the Christian plan of history.

The mosaic program can also be seen to give visual testament to the two major ambitions of Justinian’s reign: as heir to the tradition of Roman Emperors, Justinian sought to restore the territorial boundaries of the Empire. As the Christian Emperor, he saw himself as the defender of the faith. As such it was his duty to establish religious uniformity or Orthodoxy throughout the Empire.

Justinian mosaic, San Vitale, consecrated 547, Ravenna, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Who’s who in the mosaic and what they carry

In the chancel mosaic Justinian is posed frontally in the center. He is haloed and wears a crown and a purple imperial robe. He is flanked by members of the clergy on his left with the most prominent figure the Bishop Maximianus of Ravenna being labelled with an inscription. To Justinian’s right appear members of the imperial administration identified by the purple stripe, and at the very far left side of the mosaic appears a group of soldiers.

This mosaic thus establishes the central position of the Emperor between the power of the church and the power of the imperial administration and military. Like the Roman Emperors of the past, Justinian has religious, administrative, and military authority.

Clergy and Justinian (detail), Justinian mosaic, San Vitale, consecrated 547, Ravenna, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The clergy and Justinian carry in sequence from right to left a censer, the gospel book, the cross, and the bowl for the bread of the Eucharist. This identifies the mosaic as the so-called Little Entrance which marks the beginning of the Byzantine liturgy of the Eucharist. Justinian’s gesture of carrying the bowl with the bread of the Eucharist can be seen as an act of homage to the True King who appears in the adjacent apse mosaic.

Apse with Jesus Christ and St. Vitale at center, Justinian mosaic below at lower left, San Vitale, consecrated 547, Ravenna, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Chi-Rho on shield (detail), Justinian mosaic, San Vitale, consecrated 547, Ravenna, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Christ, dressed in imperial purple and seated on an orb signifying universal dominion, offers the crown of martyrdom to St. Vitale, but the same gesture can be seen as offering the crown to Justinian in the mosaic below. Justinian is thus Christ’s vice-regent on earth, and his army is actually the army of Christ as signified by the Chi-Rho on the shield.

Who’s in front?

Closer examination of the Justinian mosaic reveals an ambiguity in the positioning of the figures of Justinian and the Bishop Maximianus. Overlapping suggests that Justinian is the closest figure to the viewer, but when the positioning of the figures on the picture plane is considered, it is evident that Maximianus’s feet are lower on the picture plane which suggests that he is closer to the viewer. This can perhaps be seen as an indication of the tension between the authority of the Emperor and the church.

Justinian and Maximianus (detail), Justinian mosaic, San Vitale, consecrated 547, Ravenna, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

https://www.google.com/maps/@44.4204964,12.1967468,0a,54.8y,127.69h,143.68t/data=!3m4!1e1!3m2!1sAF1QipPExD193tQ04hhVMZ7JPwpIRgrME9mNgxf9i9LO!2e10?source=apiv3

Cite this page as: Dr. Allen Farber, “San Vitale and the Justinian Mosaic,” in Smarthistory, August 20, 2022, accessed May 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/san-vitale/.

Case Study: Empress Theodora, rhetoric, and Byzantine primary sources

Theodora mosaic, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Justinian mosaic, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Empress Theodora

The famed imperial mosaics in the church of San Vitale in Ravenna depict the sixth-century Byzantine empress Theodora across from her husband, the emperor Justinian. Empress and emperor appear at the center of each scene, larger than the other figures to show their importance, bedecked in imperial purple, and sporting lavish crowns framed by golden haloes. They process with clergy, courtiers, and soldiers into a church (although neither Justinian nor Theodora ever actually entered San Vitale in Ravenna, which was located far to the west of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople).

The Byzantine Empire, approximate boundaries, mid-6th century (underlying map © Google)

While this mosaic of the empress and her retinue in San Vitale is the only certain visual depiction of Theodora, several written descriptions of Theodora survive. The challenge for us today is interpreting these texts, because they diverge significantly in their depiction of the empress.

The writings of Prokopios

The writings of Prokopios of Caesarea, a historian during the reign of Justinian and Theodora, are our main source for their reign. Prokopios wrote several works, such as Wars and Buildings, which cast Justinian and Theodora in a favorable light and circulated widely. But Prokopios also authored a text known as the Secret History, or Anekdota (literally “unpublished things”), which was not initially intended for wide circulation and which attacked the imperial couple.

Prokopios’s Secret History survived from the Byzantine era to today in just one manuscript copy, suggesting that it was not widely reproduced in the Byzantine period. But in our time, the Secret History has become Prokopios’s most popular work, and one of the most widely read primary sources from Byzantine history.

Detail of Theodora mosaic, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Comparing primary sources

Consider the following excerpts from primary sources, which illustrate how a writer or artist could depict the same subject in a positive or negative light. As you compare these depictions of Theodora, ask yourself why these texts and images were created, what details each work emphasizes, and possible agendas these works were created to serve.

Theodora’s physical appearance

The following two statements—both written by Prokopios—describe Theodora’s physical appearance. Such descriptions of a person’s outward appearance were especially loaded in the Byzantine Empire, where it was widely believed that physical beauty mirrored inner qualities such as virtue.

| The statue [of Theodora] was indeed beautiful, but still inferior to the beauty of the Empress; for to express her loveliness in words or to portray it in a statue would be, for a mere human being, altogether impossible.

Prokopios, Buildings I.xi.2–6 |

Now Theodora was fair of face and in general attractive in appearance, but short of stature and lacking in color, being, however, not altogether pale but rather sallow, and her glance was always intense and made with contracted brows.

Prokopios, Secret History (Anekdota) x.11–2 |

Theodora’s patronage

An important duty for a Byzantine empress was undertaking charitable causes. Here you see Prokopios describe the same act of Theodora’s patronage of a women’s monastery in two very different ways.

| And these Sovereigns have endowed this convent with an ample income of money, and have added many buildings most remarkable for their beauty and costliness, to serve as a consolation for the women, so that they never should be compelled to depart from the practice of virtue in any manner whatsoever.

Prokopios, Buildings I.ix.10 |

But Theodora also concerned herself to devise punishments against the body. Harlots, for instance, to the number of more than five hundred who plied their trade in the midst of the marketplace at the rate of three obols—just enough to live on—she gathered together, and sending them over to the opposite mainland she confined them to the Convent of Repentance, as it is called, trying there to compel them to adopt a new manner of life. And some of them threw themselves from a height at night and thus escaped the unwelcome transformation.

Prokopios, Secret History (Anekdota) xvii.5–6 |

Theodora’s public Image

In addition to being described as both beautiful and charitable, it was conventional in ancient and Byzantine rhetoric to portray a good empress as modest and poised in her demeanor. Consider these final two representations of Theodora: on the left, Prokopios’s account of Theodora before she became empress, and on the right, the artistic representation of Theodora as empress in San Vitale.

| And often even in the theatre, before the eyes of the whole people, she stripped off her clothing and moved about naked through their midst, having only a girdle about her private parts and her groins, not, however, that she was ashamed to display these too to the populace, but because no person is permitted to enter there entirely naked, but must have at least a girdle about the groins.

Prokopios, Secret History (Anekdota) ix.20 |

Theodora mosaic, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

|

Rhetorical conventions

Prokopios’s background and the rhetorical conventions of his time help illuminate these apparent contradictions in the primary sources above. Prokopios came to the Byzantine capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) from Caesarea in Palestine (modern Israel). He was well educated and may have belonged to a family of the old Roman aristocracy.

In Theodora’s time, writers like Prokopios trained in classical rhetoric—the Greco-Roman tradition of persuasion through the art of public speaking—that followed highly structured formulas. Their training from an early age focused on the ability to offer a positive and negative version of something equally well. Rhetoric textbooks taught writers how to spin facts to fit the larger purpose of a text.

Prokopios deploys established rhetorical formulas to praise Justinian and Theodora in Wars and Buildings while also criticizing the imperial couple in his Secret History. As modern readers, the apparent contradictions in these works might puzzle us as we seek to separate historical fact from fiction. But educated Byzantine readers of Prokopios’s time would have easily recognized the positive and negative accounts of the imperial couple as two different rhetorical genres known as encomium and invective, in effect, two different modes of speaking about the same subject.

The gendered politics of slander

Additionally, in the Roman world to which the Byzantine Empire was heir, it was a common political strategy to slander a wife or daughter in order to damage her husband or father. From the time of Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, detractors accused female members of the imperial family of engaging in prostitution as a way to try to diminish the emperor. If he can’t even control his own family—or so the rhetoric goes—how can he possibly rule the empire?

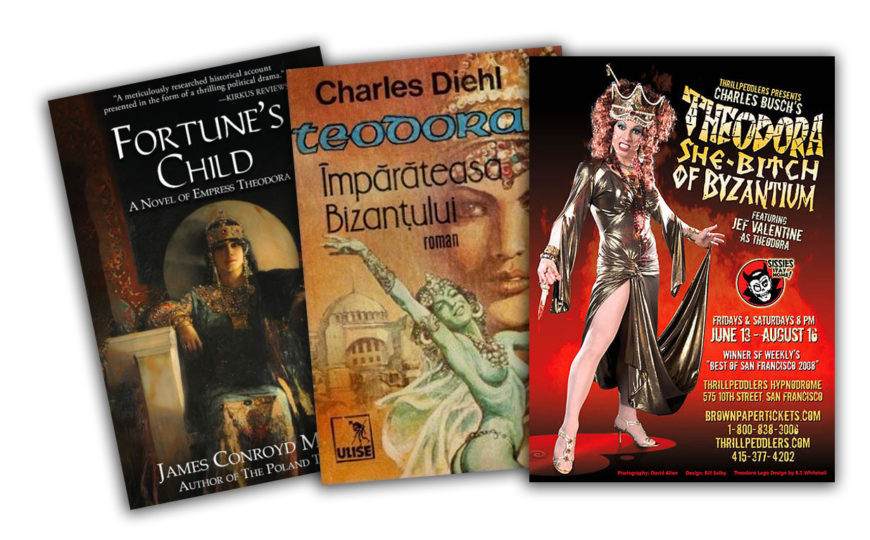

Modern receptions of the Secret History

The Secret History, which includes many negative descriptions of Theodora, is also filled with accusations against her husband, the emperor Justinian. For example, the Secret History describes Justinian as a lord of the demons who allegedly wandered the imperial palace removing his head and carrying it in his arms. But while many modern readers have dismissed such fantastical descriptions of Justinian as a demon, they have often been willing to accept lurid descriptions of Theodora from the same text as truth. Modern fascination with these passages has also inspired popular depictions of Theodora in books, theater, and film.

Popular depictions of Theodora in the modern era have often relied on Prokopios’s Secret History

Byzantine primary sources

The differing depictions of Theodora in the writings of Prokopios and the mosaics at San Vitale challenge us to consider how we approach primary sources from other periods and cultures. They remind us to be mindful of cultural conventions such as rhetoric before we accept their images and texts as literal, historical facts.

Additional resources

Smarthistory’s free Guide to Byzantine Art e-book

Anne McClanan, Representations of Early Byzantine Empresses: Image and Empire (New York; Palgrave, 2002)

Carolyn L. Connor, Women of Byzantium (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004)

Roland Betancourt, Byzantine Intersectionality: Sexuality, Gender, and Race in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020)

Cite this page as: Dr. Anne McClanan, “Empress Theodora, rhetoric, and Byzantine primary sources,” in Smarthistory, July 8, 2021, accessed May 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/theodora-rhetoric/.

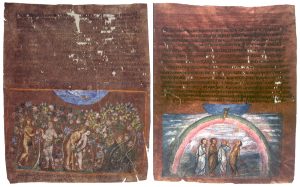

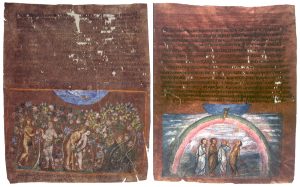

The Vienna Genesis

The fall of man and God’s covenant with Noah, from the Vienna Genesis, folio 3 recto, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 31.75 x 23.5 cm (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

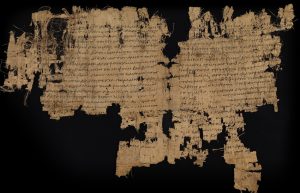

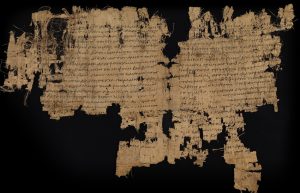

Wealthy Christian families living in the Byzantine world may have aspired to own a new kind of luxury object: the illustrated codex. Before the invention of printing in the 15th century, all texts were written or carved by hand. In the ancient world, manuscripts (texts written by hand) were found on a variety of portable surfaces. In the ancient Near East scribes wrote on clay tablets. In ancient Egypt and the ancient Greek and Roman world, information could be stored temporarily on wooden tablets coated with wax. A more lasting solution was to use scrolls made of papyrus (below): fibrous reeds that were dried in overlapping layers and then polished with a stone to create a smooth surface. Authors of papyrus scrolls usually divided their work into sections based on how much text could be held on a single scroll, leading to the concept of “chapters.”

Scripture Interpreted by Philo of Alexandria, papyrus manuscript fragment, 3rd century CE, Egypt, 20.3 x 30.5 cm (Bodleian Library, Oxford)

New materials, new possibilities

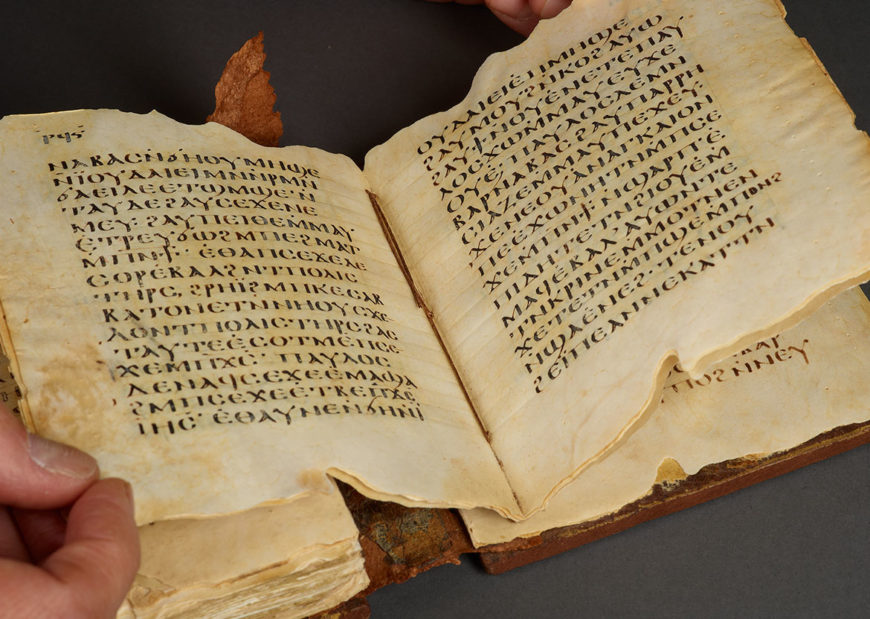

All of these materials preserved texts for the few literate members of the population, but the limitations of the materials themselves made it difficult to add illustrations to the text. Papyrus scrolls were rolled for storage and then unrolled when read, causing paint to flake off. Text was scratched into the surface of a wax or clay tablet with a stylus, so only basic shapes could be created. Some time in the first or second century, however, the parchment codex (below), a more durable and flexible means of preserving and transporting text, began to replace wax tablets and papyrus scrolls. The new popularity of the codex coincided with the spread of Christianity, which required the use of texts for both the training of initiates and ritual practices.

The codex form allowed readers to find a discrete section of text quickly and to carry large amounts of text with them, which was useful for priests who traveled from place to place to serve communities of Christians. It was also essential for a religion that relied on text to establish the details of belief and set standards of conduct for its members. The vast majority of these codices were not decorated in any way, but some contained illustrations done with tempera paint that pictured events described in the text, interpreted these events, or even added visual content not found in the text.

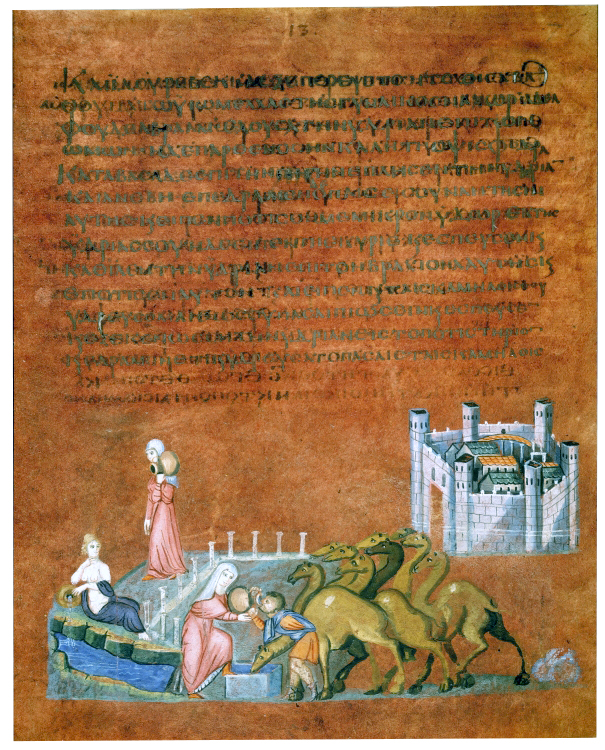

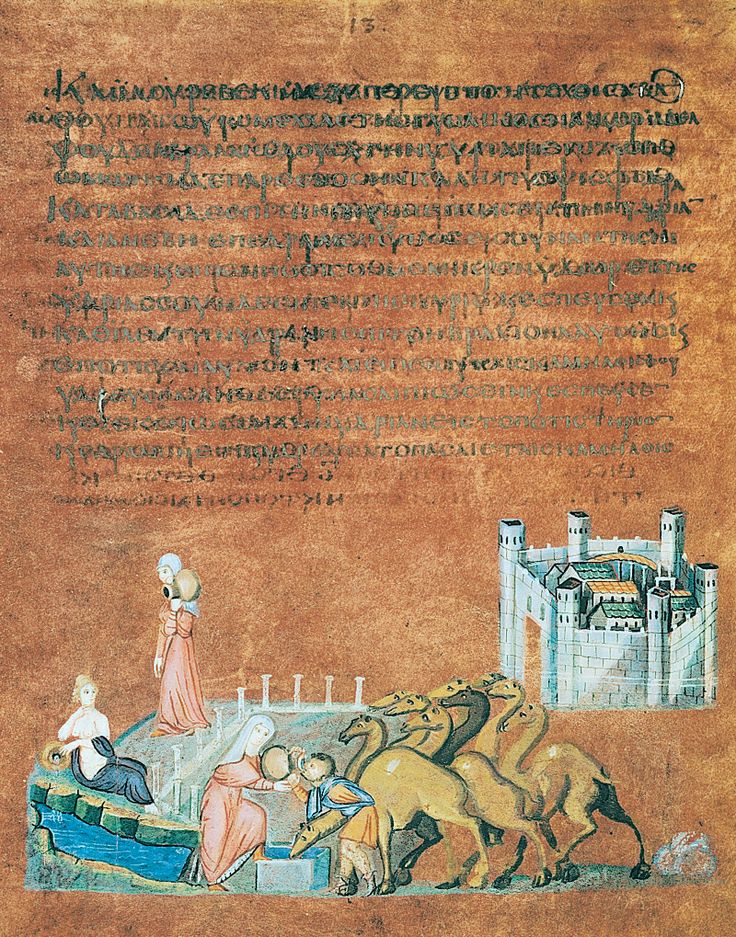

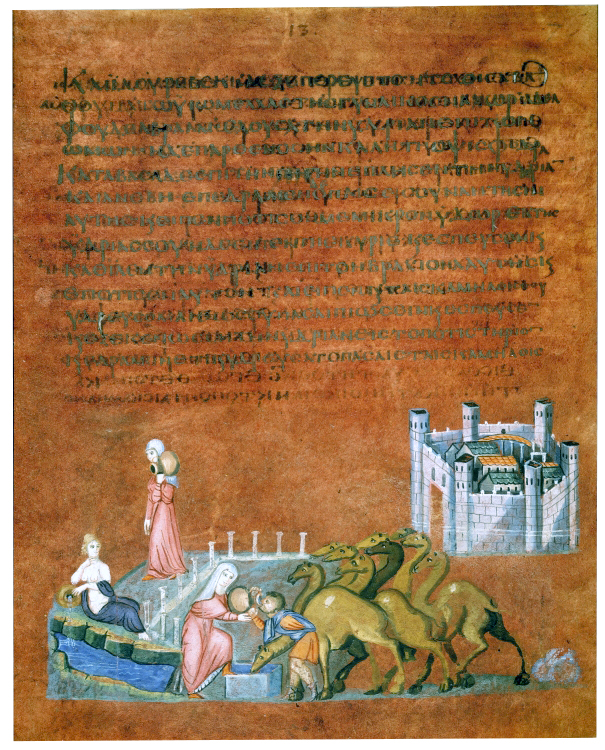

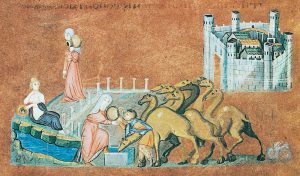

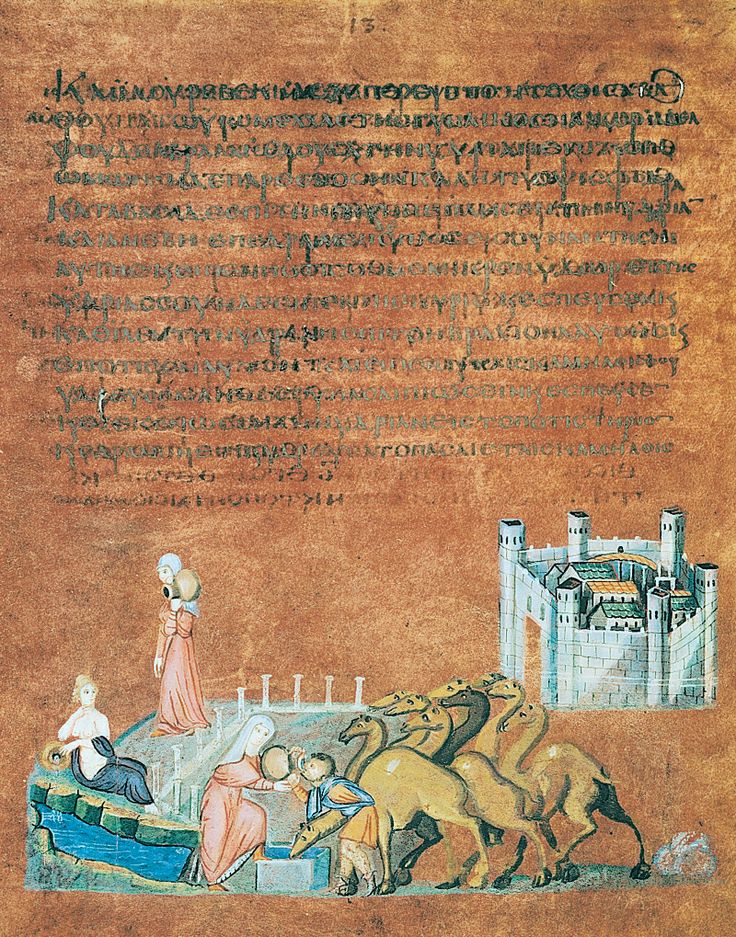

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, folio 7 recto from the Vienna Genesis, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 31.75 x 23.5 cm (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

A luxurious codex

The Early Byzantine Vienna Genesis gives us a taste of what manuscripts made for a wealthy patron, likely a member of the imperial family, might have looked like. Genesis—the first book of the Christian Old Testament—described the origin of the world and the story of the earliest humans, including their first encounters with God.

The Vienna Genesis manuscript, now only partially preserved, was a very luxurious but idiosyncratic copy of a Greek translation of the original Hebrew. The heavily abbreviated text is written on purple-dyed parchment with silver ink that has now eaten through the parchment surface in many places. These materials would have been appropriate to an imperial patron, although we have no way of knowing who that was. The Vienna Genesis may have been a luxury item intended for display, or it may have provided a synopsis of exciting stories from scripture to be read for edification or diversion by a wealthy Christian.

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, folio 7 recto from the Vienna Genesis, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 31.75 x 23.5 cm (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

Telling a story

The top half of each page of the Vienna Genesis is filled with text, while the bottom half contains a fully colored painting depicting some part of the Genesis story. In the scene above, Eliezer, a servant of the prophet Abraham, has arrived at a city in Mesopotamia in search of a wife for Isaac, Abraham’s son. The artist has used continuous narration, an artistic device popular with medieval artists but invented in the ancient world, wherein successive scenes are portrayed together in a single illustration, to suggest that the events illustrated happened in quick succession. In the upper right hand of the image a miniature walled city indicates that Eliezer has arrived at his destination. Rebecca, a kinswoman of Abraham, is shown twice. First, she walks down a path lined on one side with tiny spikes that symbolize a colonnaded street. Rebecca approaches a reclining, semi-nude woman who allows an overturned pot to drain into the river below. This is a personification of the river that feeds the well to the right, where Eliezer waits. Rebecca is shown a second time offering Eliezer and his camels a drink, a sign from God that she is to be Isaac’s wife.

Detail of Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, folio 7 recto from the Vienna Genesis, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 31.75 x 23.5 cm (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

Ancient themes, new techniques

The personification of the river reveals the image’s classical heritage, as does the use of modeling and white overpainting which lend naturalism to the garment folds and the swelling flanks of the camels.

The Vienna Genesis combines pictorial techniques familiar from the ancient world with content appropriate to a Christian audience, which is typical of Byzantine art. Though many of the details of this manuscript’s production and ownership have been lost, it remains an example of how artists combined ancient modes of expression with the most current materials and forms to create luxurious objects for wealthy patrons.

Cite this page as: Dr. Diane Reilly, “The Vienna Genesis,” in Smarthistory, April 18, 2017, accessed May 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-vienna-genesis/.

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, folio 7 recto from the Vienna Genesis, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 31.75 x 23.5 cm (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

Caught in between

It’s not hard to find inspirational quotes about the difficulty and rewards of change and transition in our lives. There is always something old that we want to hang on to and there is always something new that we want to explore. Transitions are difficult.

The visual arts have undergone numerous changes and transitions from their prehistoric origins to the present. In Europe, artists and patrons of the ancient world loved realistic details and veracity. Medieval artists and patrons instead valued symbolism and abstraction.

The artist of the Vienna Genesis was caught between these two artistic value systems. Perhaps working in Syria or in Constantinople in the early 6th century, the artist likely did not know that this book would become the oldest surviving well-preserved illustrated biblical book and an excellent example of an artist caught in a moment of transition. The Vienna Genesis is a fragment of a Greek copy of the Book of Genesis. Books were luxury items and this book was an exceptionally fine example. It was written in silver ink on parchment that had been dyed purple, the color associated with royalty and empire. There are 24 surviving folios (pages) and they are thought to have come from a much larger book that included perhaps 192 illustrations on 96 folios, each page laid out as you can see above in the example of Rebecca and Eliezer at the well.

This story is from Genesis 24. Abraham wanted to find a wife for his son Isaac and sent his servant Eliezer to find one from among Abraham’s extended family. Eliezer took ten of Abraham’s camels with him and stopped at a well to give them water. Eliezer prayed to God that Isaac’s future wife would assist him with watering his camels. Rebecca arrives on the scene and assists Eliezer, who knows that she is the woman for Isaac. This story is about God intervening to ensure a sound marriage for Abraham’s son.

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, folio 7 recto from the Vienna Genesis, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 31.75 x 23.5 cm (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

Two episodes

The illustration of this biblical story shows two episodes, which is common in medieval art. Rebecca is shown twice, as she leaves her town to get water and then assisting Eliezer at the well with his camels. On the one hand, there are clear classical elements that recall artwork from ancient Greece and Rome. Rebecca walks by a colonnade (row of columns) that recall the details of classical architecture. Some of Eliezer’s camels are shaded to emphasize that some are in the front and others in the back. The camel on the far right has one of its back legs in shadow to show a spatial relationship.

Detail of the personification of the water, folio 7 recto from the Vienna Genesis, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 31.75 x 23.5 cm (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

Ancient Greek and Roman, but also Early Christian

The figure that most obviously recalls the Ancient Greek and Roman world is the reclining nude next to the river. This figure isn’t part of the story of Rebecca and Eliezer, but serves as a personification of the source of the well’s water.

River god Arno, c. 117–138 C.E. (with Renaissance era restorations), marble (Pio Clementino Museum, Vatican) (photo: Colin, CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, detail of folio 7 recto from the Vienna Genesis, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 12-1/2 x 9-1/4″ (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

Representations of rivers and other bodies of water as people were common in the classical world. The figure’s sensuality is emphasized by her nudity and reclining pose, typical of Greek and Roman art. This stands in contrast to Rebecca’s heavily draped and fully-covered body, typical of Early Christian art.

There are also elements of the illustration that recall Early Christian art, which is the earliest medieval art. The symbolic representation of the walled city, packed with rooftops and buildings that are not represented in a spatially consistent way, is typical of medieval art, as is the colonnade in miniature. Medieval artists weren’t interested in realistic, consistent representations of space, but were satisfied with the more symbolic representations that we see here. The folds of the clothing are also simplified and reduced. The figures appear to be more cartoon-like than portraits of actual people.

Today, it is a struggle for us to reconcile the figures of Rebecca, who only reveals her hands and face, with the casual nude reclining by the water. This contrast is evidence of the mix of artistic models and sources that were present in the early sixth century. To the artist who illustrated this book, I’m sure that this mix of styles and approaches made perfect sense, and represented a culture in transition.

Cite this page as: Dr. Nancy Ross, “Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, Vienna Genesis,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed May 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/rebecca-and-eliezer-at-the-well-vienna-genesis/.