Two Etruscan Necropolises

Doors to the afterlife, Etruscan tombs were happily decorated. But as war increased, that began to change.

Video from UNESCO / Nippon Hoso Kyokai

These two large Etruscan cemeteries reflect different types of burial practices from the 9th to the 1st century BC, and bear witness to the achievements of Etruscan culture. Which over nine centuries developed the earliest urban civilization in the northern Mediterranean. Some of the tombs are monumental, cut in rock and topped by impressive tumuli (burial mounds). Many feature carvings on their walls, others have wall paintings of outstanding quality. The necropolis near Cerveteri, known as Banditaccia, contains thousands of tombs organized in a city-like plan, with streets, small squares and neighbourhoods. The site contains very different types of tombs: trenches cut in rock; tumuli; and some, also carved in rock, in the shape of huts or houses with a wealth of structural details. These provide the only surviving evidence of Etruscan residential architecture. The necropolis of Tarquinia, also known as Monterozzi, contains 6,000 graves cut in the rock. It is famous for its 200 painted tombs, the earliest of which date from the 7th century BC.

Sarcophagus of the Spouses (Version 1)

The intimacy of this clay sculpture is unprecedented in the ancient world. What can it tell us about Etruscan culture?

Sarcophagus of the Spouses (or Sarcophagus with Reclining Couple), from the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri, Italy, c. 520 B.C.E., painted terracotta, 3 feet 9 1/2 inches x 6 feet 7 inches (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Sarcophagus of the Spouses, c. 520 B.C.E., Etruscan, painted terracotta, 140 x 202 cm, found in the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses is an anthropoid (human-shaped), painted terracotta sarcophagus found in the ancient Etruscan city of Caere (now Cerveteri, Italy). The sarcophagus, which would have originally contained cremated human remains, was discovered during the course of archaeological excavations in the Banditaccia necropolis of ancient Caere during the nineteenth century and is now in Rome. The sarcophagus is quite similar to another terracotta sarcophagus from Caere depicting a man and woman that is presently housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris; these two sarcophagi are contemporary to one another and are perhaps the products of the same artistic workshop.

Upper bodies (detail), Sarcophagus of the Spouses, c. 520 B.C.E., Etruscan, painted terracotta, 140 x 202 cm, found in the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An archaic couple

Feet and shoes (detail), Sarcophagus of the Spouses, c. 520 B.C.E., Etruscan, painted terracotta, 140 x 202 cm, found in the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The sarcophagus depicts a reclining man and woman on its lid. The pair rests on highly stylized cushions, just as they would have done at an actual banquet. The body of the sarcophagus is styled so as to resemble a kline (dining couch). Both figures have highly stylized hair, in each case plaited with the stylized braids hanging rather stiffly at the sides of the neck. In the female’s case the plaits are arranged so as to hang down in front of each shoulder. The female wears a soft cap atop her head; she also wears shoes with pointed toes that are characteristically Etruscan. The male’s braids hang neatly at the back, splayed across the upper back and shoulders. The male’s beard and the hair atop his head is quite abstracted without any interior detail. Both figures have elongated proportions that are at home in the Archaic period in the Mediterranean.

Tomb of the Triclinium, c. 470 B.C.E., Etruscan chamber tomb, Tarquinia, Italy (photo: Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A banquet

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses has been interpreted as belonging to a banqueting scene, with the couple reclining together on a single dining couch while eating and drinking. This situates the inspiration for the sarcophagus squarely in the convivial (social) sphere and, as we are often reminded, conviviality was central to Etruscan mortuary rituals. Etruscan funerary art—including painted tombs—often depicts scenes of revelry, perhaps as a reminder of the funeral banquet that would send the deceased off to the afterlife or perhaps to reflect the notion of perpetual conviviality in said afterlife. Whatever the case, banquets provide a great deal of iconographic fodder for Etruscan artists.

Banquet Plaque (detail) from Poggio Civitate, early 6th century B.C.E., Etruscan, terracotta (Antiquarium di Poggio Civitate Museo Archeologico, Murlo, Italy)

In the case of the sarcophagus it is also important to note that at Etruscan banquets, men and women reclined and ate together, a circumstance that was quite different from other Mediterranean cultures, especially the Greeks. We see multiple instances of mixed gender banquets across a wide chronological range, leading us to conclude that this was common practice in Etruria. The terracotta plaque from Poggio Civitate, Murlo, for instance, that is roughly contemporary to the sarcophagus of the spouses shows a close iconographic parallel for this custom. This cultural custom generated some resentment—even animus—on the part of Greek and Latin authors in antiquity who saw this Etruscan practice not just as different, but took it as offensive behavior. Women enjoyed a different and more privileged status in Etruscan society than did their Greek and Roman counterparts.

Female figure’s face (detail), Sarcophagus of the Spouses, c. 520 B.C.E., Etruscan, painted terracotta, 140 x 202 cm, found in the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Technical achievement

Seated statue of Zeus from Poseidonia (Paestum), c. 530 B.C.E., terracotta (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Paestum; photo: Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0)

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses is a masterwork of terracotta sculpture. Painted terracotta sculpture played a key role in the visual culture of archaic Etruria. Terracotta artwork was the standard for decorating the superstructure of Etruscan temples and the coroplastic (terracotta) workshops producing these sculptures often displayed a high level of technical achievement. This is due, in part, to the fact that ready sources of marble were unknown in archaic Italy. Even though contemporary Greeks produced masterworks in marble during the sixth century B.C.E., terracotta statuary such as this sarcophagus itself counts as a masterwork and would have been an elite commission. Contemporary Greek colonists in Italy also produced high level terracotta statuary, as exemplified by the seated statue of Zeus from Poseidonia (later renamed Paestum) that dates c. 530 B.C.E.

Etruscan culture

In the case of the Caeretan sarcophagus, it is an especially challenging commission. Given its size, it would have been fired in multiple pieces. The composition of the reclining figures shows awareness of Mediterranean stylistic norms in that their physiognomy reflects an Ionian influence (Ionia was a region in present-day Turkey, that was a Greek colony)—the rounded, serene faces and the treatment of hairstyles would have fit in with contemporary Greek styles. However, the posing of the figures, the angular joints of the limbs, and their extended fingers and toes reflect local practice in Etruria. In short, the artist and his workshop are aware of global trends while also catering to a local audience. While we cannot identify the original owner of the sarcophagus, it is clear that the person(s) commissioning it would have been a member of the Caeretan elite.

Male figure’s face (detail), Sarcophagus of the Spouses, c. 520 B.C.E., Etruscan, painted terracotta, 140 x 202 cm, found in the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses as an object conveys a great deal of information about Etruscan culture and its customs. The convivial theme of the sarcophagus reflects the funeral customs of Etruscan society and the elite nature of the object itself provides important information about the ways in which funerary custom could reinforce the identity and standing of aristocrats among the community of the living.

Additional resources

This sculpture at the Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia.

L. Bonfante, ed., Etruscan Life and Afterlife: a Handbook of Etruscan Studies (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1986).

M. F. Briguet, Le sarcophage des époux de Cerveteri du Musée du Louvre (Florence: Leo Olschki, 1989).

O. J. Brendel, Etruscan Art, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

S. Haynes, Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History (Los Angeles, California: Getty Publications, 2000).

E. Macnamara, Everyday life of the Etruscans (London: Batsford, 1973).

E. Macnamara, The Etruscans (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991).

A. S. Tuck, “The Etruscan Seated Banquet: Villanovan Ritual and Etruscan Iconography,” American Journal of Archaeology 98.4 (1994): 617–628.

J. M. Turfa, ed., The Etruscan World (London: Routledge, 2013).

A. Zaccaria Ruggiu, More regio vivere: il banchetto aristocratico e la casa romana di età arcaica (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 2003).

Sarcophagus of the Spouses (Version 2)

Sarcophagus of the Spouses, Etruscan, c. 520-510 B.C.E., painted terracotta (Musée du Louvre), photo: © Louvre, dist. RMN/Philoppe Fuzeau

The freedom enjoyed by Etruscan women

One of the distinguishing features of Etruscan society, and one that caused much shock and horror to their Greek neighbors, was the relative freedom enjoyed by Etruscan women. Unlike women in ancient Greece or Rome, upper class Etruscan women actively participated in public life—attending banquets, riding in carriages and being spectators at (and participants in) public events. Reflections of such freedoms are found throughout Etruscan art; images of women engaged in these activities appear frequently in painting and in sculpture.

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses was found in Cerverteri, a town in Italy north of Rome, which is the site of a large Etruscan necropolis (or cemetery), with hundreds of tombs. The sarcophagus vividly evokes both the social visibility of Etruscan women and a type of marital intimacy rarely seen in Greek art from this period.

Sarcophagus of the Spouses, Etruscan, c. 520-510 B.C.E., painted terracotta (Musée du Louvre)

A funerary banquet?

In the sarcophagus (and another largely identical example at the Villa Giulia in Rome), the two figures recline as equals as they participate in a banquet, possibly a funerary banquet for the dead. In contemporary Greece, the only women attending public banquets, or symposia, were courtesans, not wives! The affectionate gestures and tenderness between the Etruscan man and woman convey a strikingly different attitude about the status of women and their relative equality with their husbands.

Terracotta

Aside from its subject matter, the sarcophagus is also a remarkable example of Etruscan large-scale terracotta sculpture (terracotta is a type of ceramic also called earthenware). At nearly two meters long, the object demonstrates the rather accomplished feat of modeling clay figures at nearly life-size. Artists in the Etruscan cities of Cerveteri and Veii in particular preferred working with highly refined clay for large-scale sculpture as it provided a smooth surface for the application of paint and the inclusion of fine detail.

Handling such large forms, however, was not without complications; evidence of this can be seen in the cut that bisects the sarcophagus. Splitting the piece in two parts would have allowed the artist to more easily manipulate the pieces before and after firing. If you look closely, you can also see a distinct line separating the figures and the lid of the sarcophagus; this was another trick for creating these monumental pieces—modeling the figures separately and then placing them on top of their bed.

Detail, Sarcophagus of the Spouses, Etruscan, c. 520-510 B.C.E., painted terracotta (Musée du Louvre)

Color

A really lovely characteristic of this sculpture is the preservation of so much color. In addition to colored garments and pillows, red laced boots, her black tresses and his blond ones, one can easily discern the gender specific skin tones so typical in Etruscan art. The man’s ochre flesh signifies his participation in a sun-drenched, external world, while the woman’s pale cream skin points to a more interior, domestic one. Gendered color conventions were not exclusive to the Etruscans but have a long pedigree in ancient art. Though their skin and hair color may be different, both figures share similar facial features—archaic smiles (like the ones we see in ancient Greek archaic sculptures), almond shaped eyes, and highly arched eyebrows—all typical of Etruscan art.

What were they holding?

One of the great puzzles of the sarcophagus centers on what the figures were holding. Etruscan art often featured outsized, expressive hands with suggestively curled fingers. Here the arm positions of both figures hint that each must have held small objects, but what? Since the figures are reclining on a banqueting couch, the objects could have been vessels associated with drinking, perhaps wine cups, or representations of food. Another possibility is that they may have held alabastra, small vessels containing oil used for anointing the dead. Or, perhaps, they held all of the above—food, drink and oil, each a necessity for making the journey from this life to the next.

Whatever missing elements, the conviviality of the moment and intimacy of the figures capture the life-affirming quality often seen in Etruscan art of this period, even in the face of death.

Additional resources:

The Sarcophagus in the Louvre

Etruscan Necropolises of Cerveteri and Tarquinia (UNESCO)

Etruscan Art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilrbunn Timeline of Art History

Conservation in Action: Etruscan Sarcophagi

Tomb of the Triclinium

Etruscan civilization, 750–500 B.C.E. (image: NormanEinstein, CC BY-SA 3.0) Based on a map from The National Geographic Magazine Vol.173 No.6 (June 1988)

Elaborate funerary rituals

Funerary contexts constitute the most abundant archaeological evidence for the Etruscan civilization. The elite members of Etruscan society participated in elaborate funerary rituals that varied and changed according to both geography and time.

The city of Tarquinia (known in antiquity as Tarquinii or Tarch(u)na), one of the most powerful and prominent Etruscan centers, is known for its painted chamber tombs. The Tomb of the Triclinium belongs to this group and its wall paintings reveal important information about not only Etruscan funeral culture but also about the society of the living.

An advanced Iron Age culture, the Etruscans amassed wealth based on Italy’s natural resources (particularly metal and mineral ores) that they exchanged through medium- and long-range trade networks.

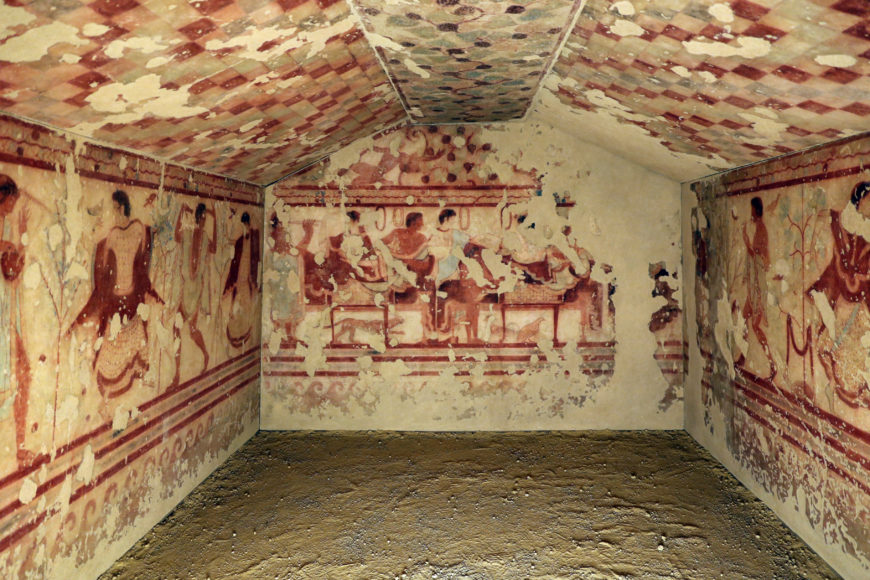

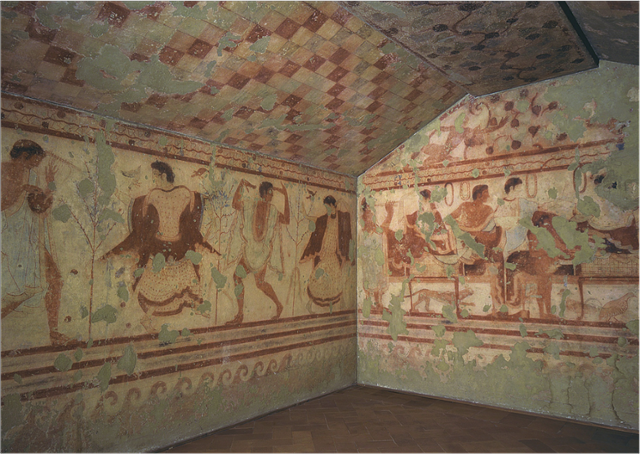

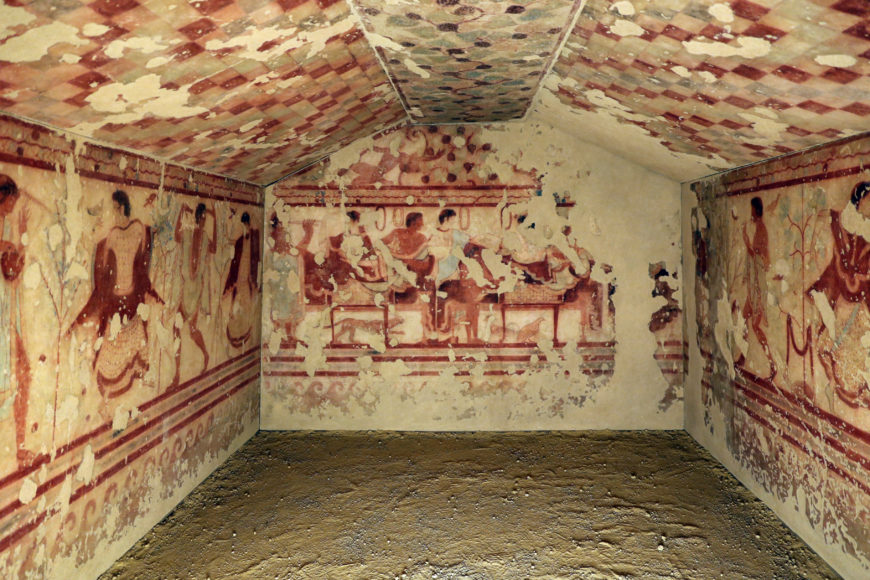

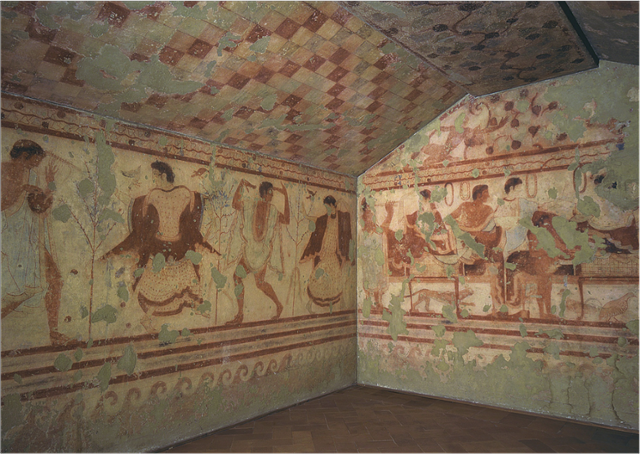

Tomb of the Triclinium, c. 470 B.C.E., Etruscan chamber tomb, Tarquinia, Italy (photo: Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Tomb of the Triclinium

The Tomb of the Triclinium (Italian: Tomba del Triclinio) is the name given to an Etruscan chamber tomb dating c. 470 B.C.E. and located in the Monterozzi necropolis of Tarquinia, Italy. Chamber tombs are subterranean rock-cut chambers accessed by an approach way (dromos) in many cases. The tombs are intended to contain not only the remains of the deceased but also various grave goods or offerings deposited along with the deceased. The Tomb of the Triclinium is composed of a single chamber with wall decorations painted in fresco. Discovered in 1830, the tomb takes its name from the three-couch dining room of the ancient Greco-Roman Mediterranean, known as the triclinium.

Tomb of the Triclinium, c. 470 B.C.E., Etruscan chamber tomb, Tarquinia, Italy

A banquet

The rear wall of the tomb carries the main scene, one of banqueters enjoying a dinner party (above). It is possible to draw stylistic comparisons between this painted scene that includes figures reclining on dining couches (klinai) and the contemporary fifth century B.C.E. Attic pottery that the Etruscans imported from Greece. The original fresco is only partially preserved; although it is likely that there were originally three couches, each hosting a pair of reclining diners, one male and one female. Two attendants—one male, one female—attend to the needs of the diners. The diners are dressed in bright and sumptuous robes, befitting their presumed elite status. Beneath the couches we can observe a large cat, as well as a large rooster and another bird.

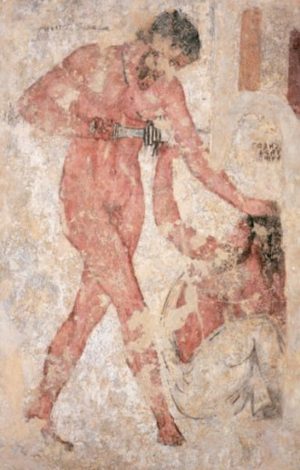

Barbiton player on the left wall (detail), Tomb of the Triclinium, c. 470 B.C.E., Etruscan chamber tomb, Tarquinia, Italy

Music and dancing

Scenes of dancers occupy the flanking left and right walls. The left wall scene contains four dancers—three female and one male—and a male musician playing the barbiton, an ancient stringed instrument similar to the lyre.

Common painterly conventions of gender typing are employed—the skin of females is light in color while male skin is tinted a darker tone of orange-brown. The dancers and musicians, together with the feasting, suggest the overall convivial tone of the Etruscan funeral. In keeping with ancient Mediterranean customs, funerals were often accompanied by games, as famously represented by the funeral games of the Trojan Anchises as described in book 5 of Vergil’s epic poem, the Aeneid. In the Tomb of the Triclinium we may have an allusion to games as the walls flanking the tomb’s entrance bear scenes of youths dismounting horses, variously described as being either apobates (participants in an equestrian combat sport) or the Dioscuri (mythological twins).

Two dancers on the right wall (detail), Tomb of the Triclinium, c. 470 B.C.E., Etruscan chamber tomb, Tarquinia, Italy

The tomb’s ceiling is painted in a checkered scheme of alternating colors, perhaps meant to evoke the temporary fabric tents that were erected near the tomb for the actual celebration of the funeral banquet.

The actual paintings were removed from the tomb in 1949 and are conserved in the Museo Nazionale in Tarquinia. As their state of preservation has deteriorated, watercolors made at the time of discovery have proven very important for the study of the tomb.

Interpretation

The convivial theme of the Tomb of the Triclinium might seem surprising in a funereal context, but it is important to note that the Etruscan funeral rites were not somber but festive, with the aim of sharing a final meal with the deceased as the latter transitioned to the afterlife. This ritual feasting served several purposes in social terms. At its most basic level the funeral banquet marked the transition of the deceased from the world of the living to that of the dead; the banquet that accompanied the burial marked this transition and ritually included the spirit of the deceased, as a portion of the meal, along with the appropriate dishes and utensils for eating and drinking, would then be deposited in the tomb. Another purpose of the funeral meal, games, and other activities was to reinforce the socio-economic position of the deceased person and his/her family: a way to remind the community of the living of the importance and standing of these people and thus tangibly reinforce their position in contemporary society. This would include, where appropriate, visual reminders of socio-political status, including indications of wealth and civic achievements, notably public offices held by the deceased.

Additional resources

Etruscan Necropolises of Cerveteri and Tarquinia, UNESCO

L. Bonfante, editor, Etruscan Life and Afterlife: a Handbook of Etruscan Studies (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1986).

O. J. Brendel, Etruscan Art, 2nd edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

P. Duell, “The tomba del Triclinio at Tarquinia,” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, volume 6 (1927), pp. 5–68.

S. Haynes, Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2000).

R. R. Holloway, “Conventions of Etruscan Painting in the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing at Tarquinii,” American Journal of Archaeology, volume 69, number 4 (1965), pp. 341–47.

A. Naso, La pittura etrusca: guida breve (Rome: “L’Erma” di Bretschneider, 2005).

M. Pallottino, Etruscan Painting (Geneva: Skira, 1952).

S. Steingräber, Etruscan painting: catalogue raisonné of Etruscan wall paintings (New York: Johnson, 1985).

S. Steingräber, Abundance of Life: Etruscan Wall Painting (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2006).

J. M. Turfa, editor, The Etruscan World (London: Routledge, 2013).

A. Zaccaria Ruggiu, More regio vivere: il banchetto aristocratico e la casa romana di età arcaica (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 2003).

The François Tomb

The François Tomb is chock-full of elaborate frescoes with complicated messages we may never fully understand.

The archeological site of the ancient Etruscan city of Vulci, Italy (photo: Robin Iversen Rönnlund, CC BY-SA 3.0)

When Alessandro François and Adolphe Noël des Vergers entered the so-called François Tomb (named for its discoverer) in 1857, they described a magnificent treasure trove in which ancient Etruscan warriors were sleeping on their funeral couches, surrounded by grave goods, armaments, and brilliant tableaux on painted walls. This exceptional tomb from the Ponte Rotto necropolis in Vulci served as a familial burial monument and was used for several centuries in the Hellenistic period.

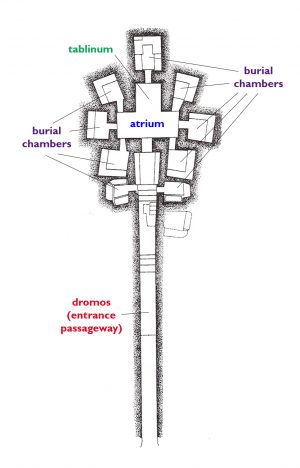

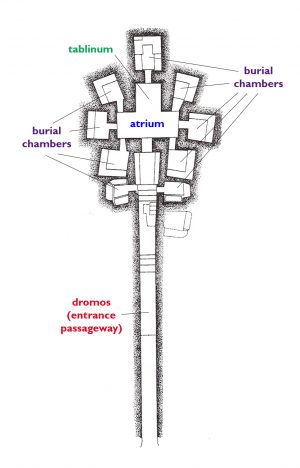

Plan of the François Tomb, Vulci

The Etruscans believed that the afterlife mirrored their own world, so they provided elaborate “homes” for their dead. The ground plan of the François Tomb is essentially a T shape, with two main chambers (called the atrium and tablinum after the rooms of typical Italo-Roman houses). The main chambers are arranged perpendicularly, with small burial chambers branching out from all sides.

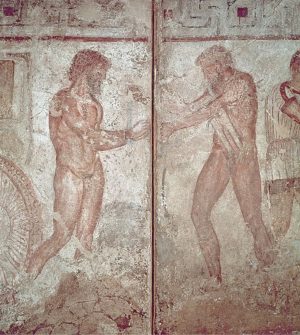

The François Tomb is famous largely because of the frescoes of its main chamber, which can be dated to the fourth century B.C.E. Unlike most Etruscan tomb paintings, the François tomb frescoes seem to include battle scenes — making it a rare, early example of ancient history painting.

Though scholars still have many questions surrounding the exact meanings of these paintings, they reflect important Etruscan ideas about history, and they would have helped reinforce shared narratives about ancestry and the past as family members continually visited the tomb to inter the newly deceased.

Dazzling frescoes

Frescoes fill the walls and ceiling of the tomb. (The original frescoes were removed by a collector in the 19th century, and replaced in the tomb itself by reproductions.) The ceiling is designed to look like the interior of a building with a timber-framed roof structure, while the walls include various figural representations and geometric designs.

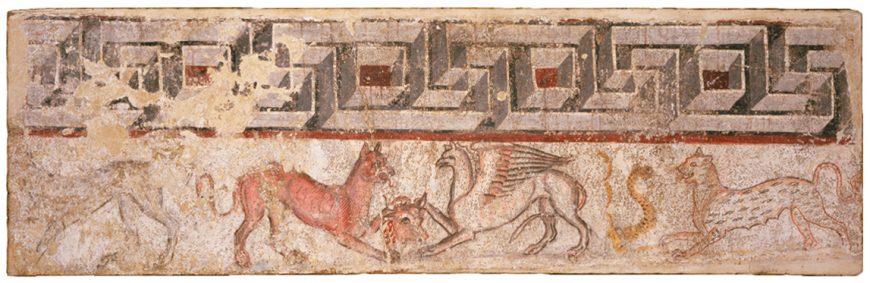

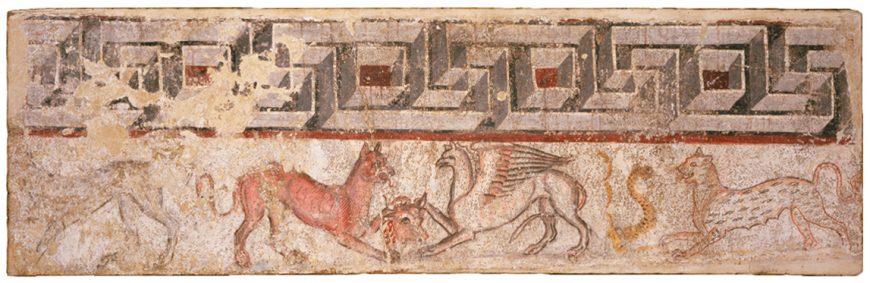

Frieze with Greek key pattern and hunting scene, atrium of the François Tomb, Vulci (Villa Albani, Rome)

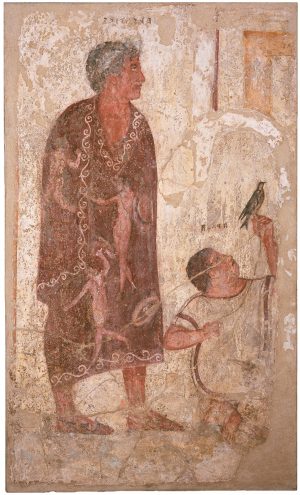

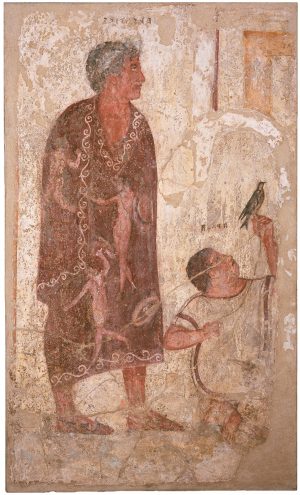

Portrait of Vel Saties, atrium of the François Tomb, Vulci (Villa Albani, Rome)

The atrium, which was the first room a visitor would enter, has the most elaborate frescoes. At the upper margin of the wall, there is a small running frieze in two registers: a Greek key pattern on top, with a hunting scene below. Under the hunting scene are larger scenes featuring human figures depicted at nearly life size.

Although one wall was badly damaged, most of the figures are well-preserved and labeled with text. From this text we know that these figures include a mix of mythological characters (including Sisyphus, Eteocles and Polynices killing each other, and Ajax raping Cassandra) and historical figures, including the founder of the tomb, an Etruscan aristocrat named Vel Saties. This full-length portrait of Vel Saties wearing a toga picta has garnered acclaim as the first such portrait in western art. [1] It is likely that the lowest quarter of the wall was obscured by stone benches, although not all of these benches have been preserved.

Scenes from mythology and history

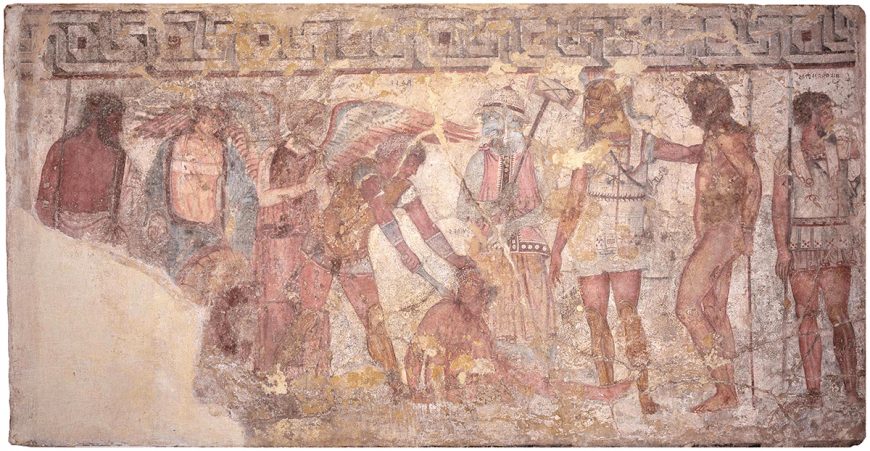

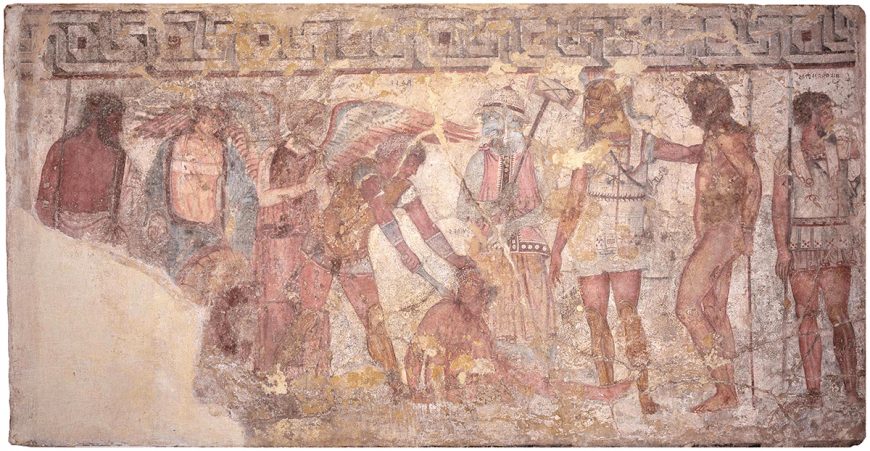

The tablinum, or rear room of the tomb, also has benches at the bottom, a fresco representing a running meander at the top, and a scene featuring human figures in between. There are a few differences in the iconography that clearly separate the atrium and tablinum. First, the tablinum does not have a hunting scene below the meander; second, the ceiling patterns are different; and finally, the figural fresco is made up of two narrative scenes, each with labeled characters.

Achilles sacrificing Trojan prisoners to the shade of Patroclus, tablinum of the François Tomb, Vulci (Villa Albani, Rome)

On the left-hand side of the tomb, there is a scene of Achilles sacrificing Trojan prisoners to the shade of Patroclus.

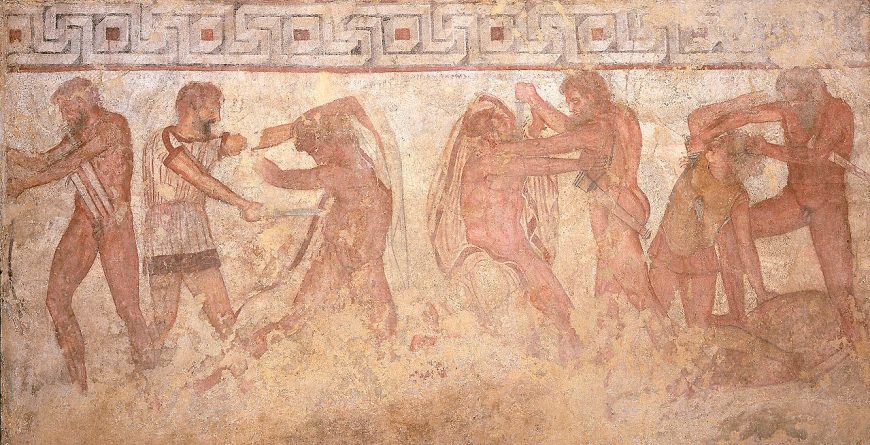

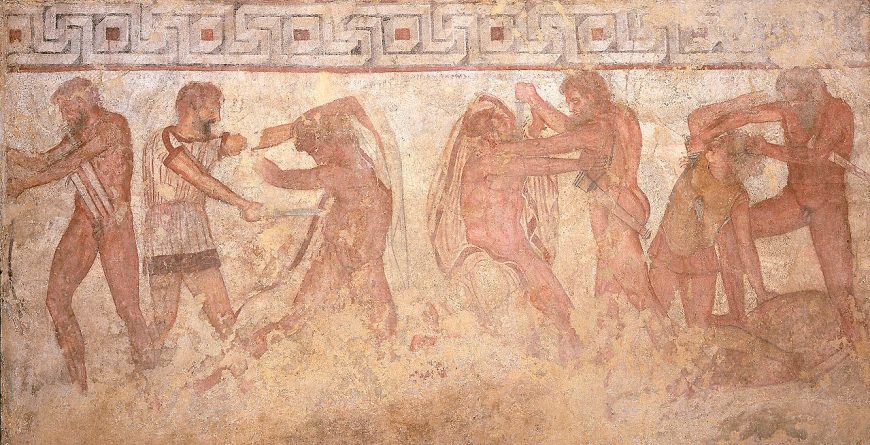

The right-hand side of the tomb shows a battle between two groups of Etruscans. It is this battle scene that has drawn the majority of historical attention. The figures are arranged into a series of dueling pairs on the long wall. Inscriptions identify the men on both sides as Etruscan, but only the figures who appear to be losing are identified with a specific city. This discrepancy has led scholars to believe that the winners are from Vulci. Because many of the dying men are only partially clothed, this scene has been interpreted as a nocturnal ambush: surprised in their sleep, the defeated figures were apparently not able to fully dress before the fighting started.

Battle scene, tablinum of the François Tomb, Vulci (Villa Albani, Rome)

A link between text and image

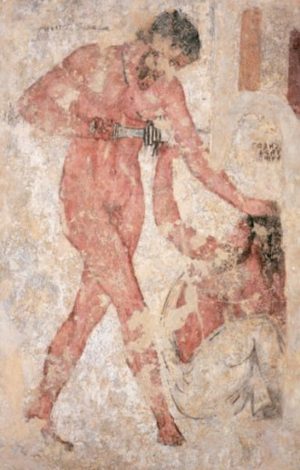

Mastarna freeing Caelius Vibenna, tablinum of the François Tomb, Vulci (Villa Albani, Rome)

Rounding the corner of the fresco is a scene derived from Rome’s legendary history. Mastarna (perhaps an alternate name for Servius Tullius, the legendary sixth king of Rome) frees Caelius Vibenna, an Etruscan aristocrat who aided Rome’s founder Romulus in his wars against Titus Tatius. Although these two men are portrayed nude (in the manner of mythological figures) there is some evidence that both were considered historical figures.

These paintings represent an important potential link between ancient visual and textual sources. The Roman emperor Claudius claimed in a speech that Mastarna was the Etruscan name of Rome’s sixth king, Servius Tullius, who was a friend of Caelius Vibenna (ILS 212). This is very similar to what is portrayed in the frescoes in the François tomb, and so the tomb’s iconography seems to provide independent confirmation of Claudius’ account.

Many scholars interpret the tomb’s iconography as being pro-Etruscan and anti-Roman. Since the Roman state made substantial territorial conquests in Etruria during the fourth century B.C.E., when the tomb was founded, the deployment of the iconography of Caelius Vibenna and Mastarna could have been a symbol of cultural pride among the Etruscans.

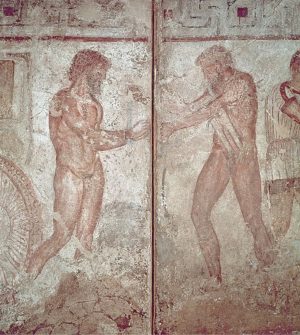

Camillus slaying Gaius Tarquinius, atrium of the Francois Tomb, Vulci (Villa Albani, Rome)

Unanswered questions

Despite widespread agreement about the fresco of Mastarna and Caelius Vibenna, questions remain about the meaning of many of the other frescoes in the François tomb.

The atrium fresco depicts Camillus killing a figure identified as “Gaius Tarquinius of Rome.”

While both Camillus and Tarquinius are figures from early Roman history, their presence in the painting is not clearly understood. The name Tarquinius may refer to either of two male Tarquin rulers (or Tarquinii) from early Roman history; however, their first names were not Gaius, but Lucius, and neither of these men was killed by Camillus. Both Tarquinii lived around the time of Mastarna in the 6th century B.C.E., whereas Roman authors believed that Camillus lived about a century later, closer in time to the date of the tomb’s construction. To further complicate things, according to Roman tradition, Camillus was famous for defeating Etruscans. His presence in the tomb and his killing of Tarquinius are thus both mysterious.

Scholarly opinion is also divided on the relationship between the Camillus/Tarquinius fresco and the other historical fresco. Many scholars see them as part of the same narrative; others, however, argue that the two must be kept separate. This debate is unlikely to be resolved unless new evidence is discovered.

Mysteries remain

The François Tomb is rightly celebrated for its elaborate decor. Although we cannot fully understand the choices made by the tomb’s patron, it seems likely that the frescoes were created to deliver a specific message. This message may have been political (pro-Etruscan/anti-Roman), religious (since most scenes focus on bloodshed), familial (portraying the family history of the owners), or ethical (illustrating moral qualities that were important to the owners). All of these interpretations have been suggested, and it is possible that all of them are correct—that is, that the owner of the tomb had all of these aspects in mind when choosing the iconography. It is the historical fresco, however, that has captured the most interest, as it seems to preserve rare information about Etruscan historical thought.

We may never know the answers to many of these questions, but the François Tomb remains a shining example of Etruscan fresco painting that offers us a glimpse into the tumultuous history of the ancient Mediterranean world.

[1] See Lisa C. Pieraccini, “Etruscan Wall Painting: Insights, Innovations, and Legacy” in Sinclair Bell and Alexandra A. Carpino, A Companion to the Etruscans (John Wiley & Sons, 2016), p. 256.

Additional resources:

The François Tomb at the Southern Etrurian Archaeological Heritage website (in Italian)

Image gallery of the frescoes

Vulci Park website with image gallery

B. Andreae, “Die Tomba François. Anspruch und historische Wirklichkeit eines etruskischen Familiengrabes.” In B. Andreae, A. Hoffman, C. Weder-Lehman (eds.), Die Etrusker: Luxus für das Jenseits. (Munich: Hirmer, 2004), pp. 176-207.

L. Bonfante Warren,“Roman Triumphs and Etruscan Kings.” The Journal of Roman Studies 60 (1970), pp. 49-66.

F. Buranelli and S. Buranelli, La Tomba François di Vulci. (Rome: Quasar, 1987).

F. Coarelli, F. “Le pitture della tomba François a Vulci : una proposta di lettura.” Dialoghi di Archeologia 3 (1983), pp. 43-69.

T. J. Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome (London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 135-141.

M. Cristofani, “Ricerche sulle pitture della tomba François di Vulci. I fregi decorativi,” Dialoghi di Archeologia 1 (1967), pp. 189-219.

N. T. de Grummond, Etruscan Myth, Sacred History, and Legend. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum, 2006), pp. 175-180, 197-199.

Jean Gagé, “De Tarquinies à Vulci : Les guerres entre Rome et Tarquinies au IVe siècle avant J.-C. et les fresques de la « Tombe François »” Mélanges d’archéologie et d’histoire publié par l’Ecole française de Rome 74 (1962), pp. 79-122.

Peter J. Holliday, “Narrative structures in the François tomb,” in Narrative and event in ancient art, (Cambridge, 1988), pp. 175-197.

A. Hus. Vulci Étrusque et Étrusco-Romaine. (Paris: Klincksieck, 1972).

Jaclyn Neel, Early Rome: Myth and Society (Wiley, 2017).

Jaclyn Neel, “The Vibennae: Etruscan Heroes and Roman Historiography” Etruscan Studies 20.1:1-34.

A. Sgubini Moretti (ed), Eroi Etruschi e Miti Greci. (Rome: Soprintendenza per i beni archeologici dell’Etruria meridionale, 2004).

Tomb of the Reliefs

All signs point to a party: cushions, drinking equipment, and armor hung on the wall … but a party in a tomb?

Tomb of the Reliefs, late 4th or early 3rd century B.C.E., Necropolis of Banditaccia (Cerveteri), Italy (photo, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The banquet is over, the dining equipment is stowed, and the warriors sleep on in this Etruscan dining room, yet the evocative signs of a lively scene draw the viewer into the ancient world. These evocations of an Etruscan banquet—from the cushions to the drinking equipment to the armor hung on pegs on the walls—are situated firmly in the funereal sphere, one that is replete with reminders not only of life but also of death. In tomb interiors we find some of our most important and compelling evidence for an understanding of the first millennium B.C.E. world of the Etruscans.

Entrance (dromos), Tomb of the Reliefs, late 4th-early 3rd century B.C.E., Necropolis of Banditaccia (Cerveteri), Italy (photo, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Tomb of the Reliefs (Italian: Tomba dei Rilievi) is a late fourth or early third century B.C.E. rock-cut tomb (hypogeum) located in the Banditaccia necropolis of the ancient Etruscan city-state of Caere (now Cerveteri) in Italy (a necropolis is a large, ancient cemetery). The tomb takes its name from a series of painted stucco reliefs that cover the walls and piers of the tomb chamber itself. Unlike some of its neighbors that are covered mounds of earth (tumulus-type tombs), the Tomb of the Reliefs is of the rock-cut type and was excavated at a considerable depth in the bedrock, approached by a steep dromos (entranceway). This elite tomb once accommodated several dozen burials and is located, likely not by accident, close to an important tumulus-type tomb from the earlier Orientalizing period.

Inside the tomb

The plan of the tomb is roughly quadrangular. The entire tomb and all of its features have been carved from the bedrock (a type of volcanic mudstone known as tufa). The central block of the room, supported by two piers, is flanked by a series of niches for burials that have been styled to resemble the dining couches (klinai) of the ancient world. Decorative pilasters with volute (scroll-shaped) capitals separate the niches one from the other (see image below).

The tomb’s bas relief (low relief) decoration consists of carved bedrock features that have been stuccoed and painted. The decorative schema evokes the interior of an aristocratic house that is prepared to host a banquet or drinking party. The provisions for banqueters include cups and strainers hanging from pegs. The soldiers’ armor—shields, helmets, greaves (protective armor for the lower leg)—has been stowed by hanging it from pegs. The pilasters are also decorated, with the items depicted including a range of tools and implements as well as the depiction of a small carnivore, perhaps a weasel.

Detail of central niche on rear wall, Tomb of the Reliefs, late 4th or early 3rd century B.C.E., Necropolis of Banditaccia (Cerveteri), Italy (photo, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Beneath the central niche of the rear wall we find an allusion to the afterlife. There, under the side table we find, in relief, the hellhound Cerberus and an anguiped (serpents for legs) demon—perhaps the Etruscan god Charun who conducted the souls of the departed to the afterlife? This central niche, equipped with footstool, may have been intended for the male and female heads of the family.

The Matunas family is identified as the owner by way of an inscribed cippus (a small pillar). The inscription reads “Vel Metunas, (son) of Laris, who this tomb built.” A locked strongbox included in the relief may be meant to represent the container for storing the records of the family’s deeds (res gestae).

The Tomb of the Reliefs is unusual in the corpus of Etruscan tombs, both for its richness and for its decorative scheme. The Matunas family, among the elite of Caere, make a fairly strong statement, by means of funerary display, about their familial status and accomplishments, even at a time when the cultural autonomy of the Etruscans—and of Caere itself—had already begun to wane. The funeral banquet remains an important and vibrant theme for Etruscan funerary art throughout the course of the Etruscan civilization. This convivial and festive rendering demonstrates to us that the funeral banquet not only sent the deceased off to the afterlife but also reinforced ties and status reminders among the community of the living.

Additional resources:

Tomb of the Reliefs (from Archaeological Heritage in Southern Etruria)

Etruscan Tombs from the Toledo Museum of Art

H. Blanck and G. Proietti, La Tomba dei Rilievi di Cerveteri (Rome: De Luca, 1986).

O. J. Brendel, Etruscan Art. 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995)

M. Cristofani, “Le iscrizioni della tomba dei Rilievi di Cerveteri,” Studi etruschi 2 (1966), vol. 34, 221-238.

M. Cristofani, “I leoni funerari della tomba dei rilievi di Cerveteri,” Archeologia classica 20 (1968) 321-323.

S. Haynes, Etruscan Civilization: a Cultural History (Los Angeles, California: Getty Publications, 2000).

F. Prayon, Frühetruskische Grab- und Hausarchitektur (Heidelberg : F.H. Kerle, 1975).

S. Steingräber, Abundance of Life: Etruscan Wall Painting (Los Angeles, California: Getty Publications, 2006).

J. M. Turfa, ed. The Etruscan World (London: Routledge, 2013).