Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Cathedral of Notre Dame de Chartres,” in Smarthistory, December 18, 2015, accessed June 5, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/cathedral-of-notre-dame-de-chartres-part-1-of-3/.

Gothic Architecture

Abbey Church of Saint-Denis

The Abbey Church of Saint Denis is known as the first Gothic structure and was developed in the 12th century by Abbot Suger.

The Abbey Church of Saint Denis, also known as the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Denis, is a large medieval abbey church in the commune of Saint Denis, now a northern suburb of Paris. This site originated as a Gallo-Roman cemetery in late Roman times. Around 475 CE, St. Genevieve established a church at this site. In the 7th century, this structure was replaced by a much grander construction, on the orders of Dagobert I, King of the Franks.

The Basilica of Saint Denis is an architectural landmark, the first major structure of which a substantial part was designed and built in the Gothic style . Both stylistically and structurally, it heralded the change from Romanesque architecture to Gothic architecture . Before the term “Gothic” came into common use, it was known as the “French Style.”

Saint Denis is a patron saint of France and, according to legend, was the first Bishop of Paris. Legend says that he was decapitated on the Hill of Montmartre and subsequently carried his head to the site of the current church, indicating where he wanted to be buried.

Dagobert I refounded the church as the Abbey of Saint Denis, a Benedictine monastery. Dagobert also commissioned a new shrine to house the saint’s remains; it was created by his chief counselor, Eligius, a goldsmith by training.

Abbot Suger

Abbot Suger (circa 1081-1151), Abbot of Saint Denis from 1122 and a friend and confidant of French kings, had been given the abbey as an oblate at the age of 10 and began work around 1135 on rebuilding and enlarging it.

Suger was the patron of the rebuilding of Saint Denis, but not the architect, as was often assumed in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In fact it appears that two distinct architects, or master masons, were involved in the 12th century changes. Both remain anonymous, but their work can be distinguished stylistically. The first, who was responsible for the initial work at the western end, favored conventional

Suger’s western extension was completed in 1140 and the three new chapels in the narthex were consecrated on June 9th of that year. On completion of the west front, Abbot Suger moved on to the reconstruction of the eastern end. He wanted a choir (chancel) that would be suffused with light. To achieve his aims, Suger’s masons drew on the new elements that had evolved or been introduced to Romanesque architecture: the pointed arch , the ribbed vault , the ambulatory with radiating chapels, the clustered columns supporting ribs springing in different directions, and the flying buttresses , which enabled the insertion of large clerestory windows. This was the first time that these features had all been brought together. The new structure was finished and dedicated on June 11th of 1144, in the presence of the King.

Thus, the Abbey of Saint Denis became the prototype for further building in the royal domain of northern France. Through the rule of the Angevin dynasty , the style was introduced to England and spread throughout France, the Low Countries, Germany, Spain, northern Italy, and Sicily.

The dark Romanesque nave , with its thick walls and small window openings, was rebuilt using the latest techniques, in what is now known as Gothic. This new style, which differed from Suger’s earlier works as much as they had differed from their Romanesque precursors , reduced the wall area to an absolute minimum. Solid masonry was replaced with vast window openings filled with brilliant stained glass and interrupted only by the most slender of bar tracery—not only in the clerestory but also, perhaps for the first time, in the normally dark triforium level. The upper facades of the two much-enlarged transepts were filled with two spectacular rose windows . As with Suger’s earlier rebuilding work, the identity of the architect or master mason is unknown.

The abbey is often referred to as the “royal necropolis of France” as it is the site where the kings of France and their families were buried for centuries. All but three of the monarchs of France from the 10th century until 1789 have their remains here. The effigies of many of the kings and queens are on their tombs, but during the French Revolution , those tombs were opened and the bodies were moved to mass graves.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and the ambulatory at St. Denis

Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and the ambulatory at St. Denis,” in Smarthistory, December 5, 2015, accessed June 5, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/birth-of-the-gothic-abbot-suger-and-the-ambulatory-at-st-denis/.

Chartres Cathedral

Cathedral of Notre Dame de Chartres

Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Paris

The Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Paris

The fire that engulfed the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris was a terrible tragedy—though not an unusual one.

The Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Paris, begun 1163. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker (recorded before the fire)

.jpg)

April 2019 fire at Notre Dame de Paris (Photo: Milliped , CC BY-SA 4.0)

The fire

The blaze that engulfed the Cathedral of Notre Dame on the small Island known as the Île de la Cité in Paris in April 2019 was a terrible tragedy. Though it may not give us much comfort to learn that the total or partial destruction of churches by fire was a fairly common occurrence in medieval Europe, it does provide some perspective. For example, a fire destroyed most of Chartres Cathedral in 1020 (and again in 1194), in the city of Reims, the cathedral was badly damaged in a fire in 1210, and at Beauvais, the cathedral was rebuilt after a fire in the 1180s. The list goes on and on.

During the medieval periods of the Romanesque and the Gothic (c. 1000-1400), church fires were less frequent than they had been previously due to the development of stone vaulting (which began to replace the timber ceilings commonly found in European churches). But even a stone vault, as we saw at Notre Dame in Paris, is itself protected by a timber roof (sometimes rising more than 50 feet above the stone vaulting and pitched to prevent the accumulation of rain and snow), and this is what caught fire.

Île de la Cité, Paris

Art historian Caroline Brazelius, who has worked on the building for years said, “between the vaults and the roof, there is a forest of timber” — old, dry, porous, and highly flammable timber. Still, photographs of the interior show at least some of the stone vaulting survived the recent fire. The builders of Notre Dame used Parisian limestone, but, as Brazelius notes “when it’s exposed to fire, stone is damaged. It doesn’t actually burn….It becomes friable. It chips, and it’s no longer structurally sound.”

Built, modified, rebuilt, and restored

Churches are often an amalgamation of architectural styles, the result of building campaigns and modifications undertaken at different times, some due to fire, some due to the desire for what a new style represents, and some due to (often inaccurate) restoration efforts. And on a single site, churches were often built and rebuilt — and this is the case with Notre Dame in Paris. Before the Gothic-style church was built, a Carolingian church occupied the site (it was destroyed during the 9th century Viking invasions), and before that, a 6th century Merovingian Church stood on the site.

Léonard Gaultier, View of Paris, 1607, engraving ( Bibliothèque nationale de France )

If we go back further, to the pre-Christian era, Julius Caesar’s armies famously conquered much of what we call France today (Roman Paris dates back to 52 BCE). Archaeological evidence suggests that a pagan temple and then a Christian basilica were built on this site. The ancient Romans also built a palace for the emperor on the Île de la Cité, and after the Roman empire collapsed, Clovis I, King of the Franks (who converted to Christianity) established his palace there as well. The Île de la Cité would remain the location of a royal residence until the 14th century. As one historian has noted, “Notre Dame … was not only a religious but also a royal monument that displayed the might of the church and the monarchy, each enhancing the power of the other.” [1]

Crossing, Notre Dame de Paris, c. 1163-1250 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Gothic Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris took nearly 100 years to complete (c. 1163-1250) and modifications, restorations, and renovations continued for centuries after. The early Gothic style employed at the beginning of the campaign became outdated and the later Gothic style, the Rayonnant, became fashionable and can be seen in the transepts. The crossing spire that the world watched fall while engulfed in flames was a reproduction created during a 19th-century restoration campaign.

In the following centuries, the church (and its sculptural decoration) survived multiple episodes of intentional destruction: during the Protestant Reformation (due to Protestant objection to religious imagery), and during the revolutions of 1789 and 1830 (because of the church’s close association with the monarchy). It remained in a neglected state until Victor Hugo’s novel, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) revived popular interest the building.

View of Notre Dame de Paris, c. 1163-1250 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

As of this writing, just a few days after the April 15th blaze, evaluation of the damage caused by the fire is only just beginning, but a reported one billion dollars has been already been raised to support the reconstruction of Notre Dame de Paris.

[1] Avner Ben-Amos, “Monuments and Memory in French Nationalism,” History and Memory , volume 5, number 2 (1993), pp. 50–81 .

Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “The Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Paris,” in Smarthistory, April 24, 2019, accessed June 5, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/notre-dame-fire/.

Reims Cathedral

Reims Cathedral (Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Reims), begun 1211, Reims, France

Reims Cathedral and World War I

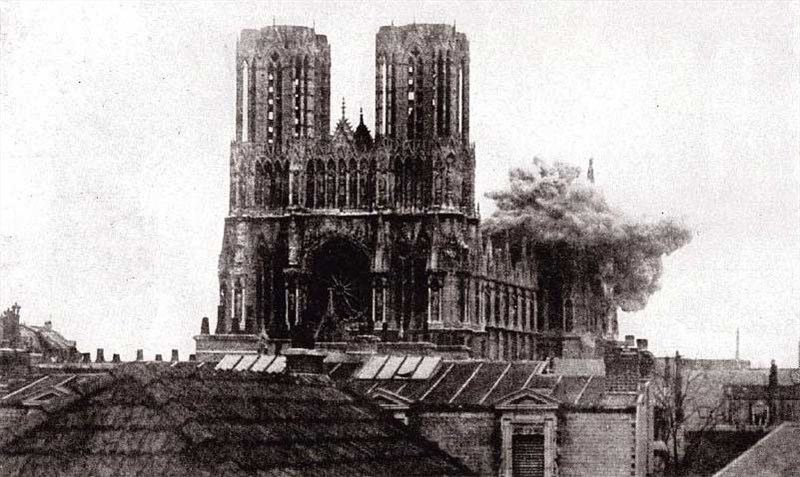

Shell bursting on the cathedral at Reims, from Collier’s New Photographic History of the World’s War, 1918

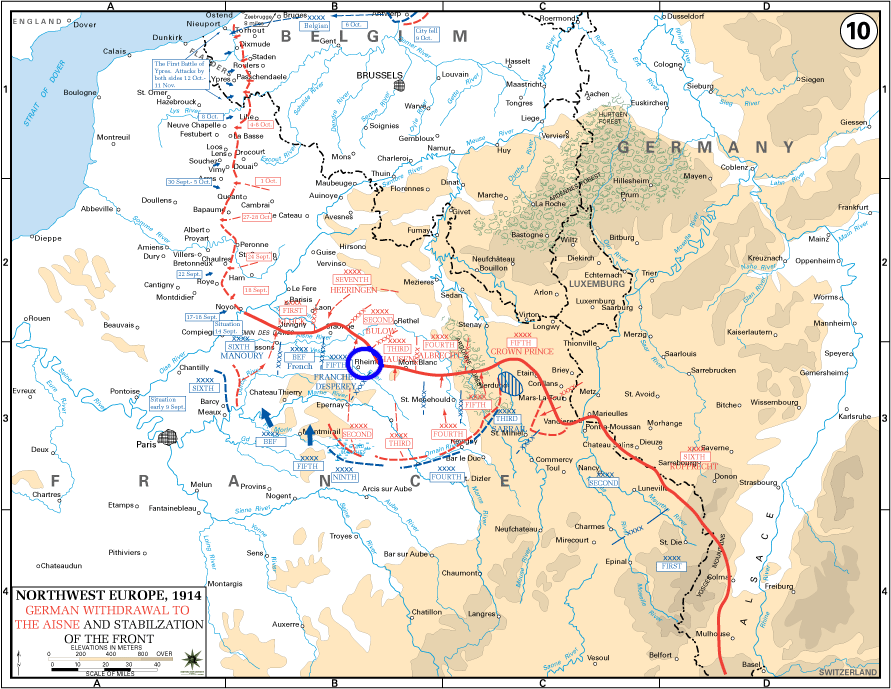

Map of the Western Front, 1914, with Reims circled in blue (map: The History Department of the United States Military Academy, CC0)

The facts…?

World War I officially started July 28, 1914. Originally it was believed that the “situation” would clear itself up by no later than Christmastime. Instead, it took over four long and grueling years, and resulted in more than 15 million deaths. Early on in the conflict, the German army moved into northeastern French territory. This was the beginning of the Western Front. The expeditious land grab by the Germans included the city of Reims. Reims had a well-established history, from its days as a bustling hub of the Roman Empire, to becoming a center of French culture in the early Middle Ages. Additionally, Reims was the “Coronation Capital,” so to speak, the traditional location for the coronation of French kings. It was also home to a magnificent high Gothic cathedral, Notre-Dame de Reims. By early September, the French had forced the Germans to retreat and though the French regained the town, the Germans stayed close by for the entirety of the war.

View of Reims cathedral over the rooftops of the city in 2014 (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

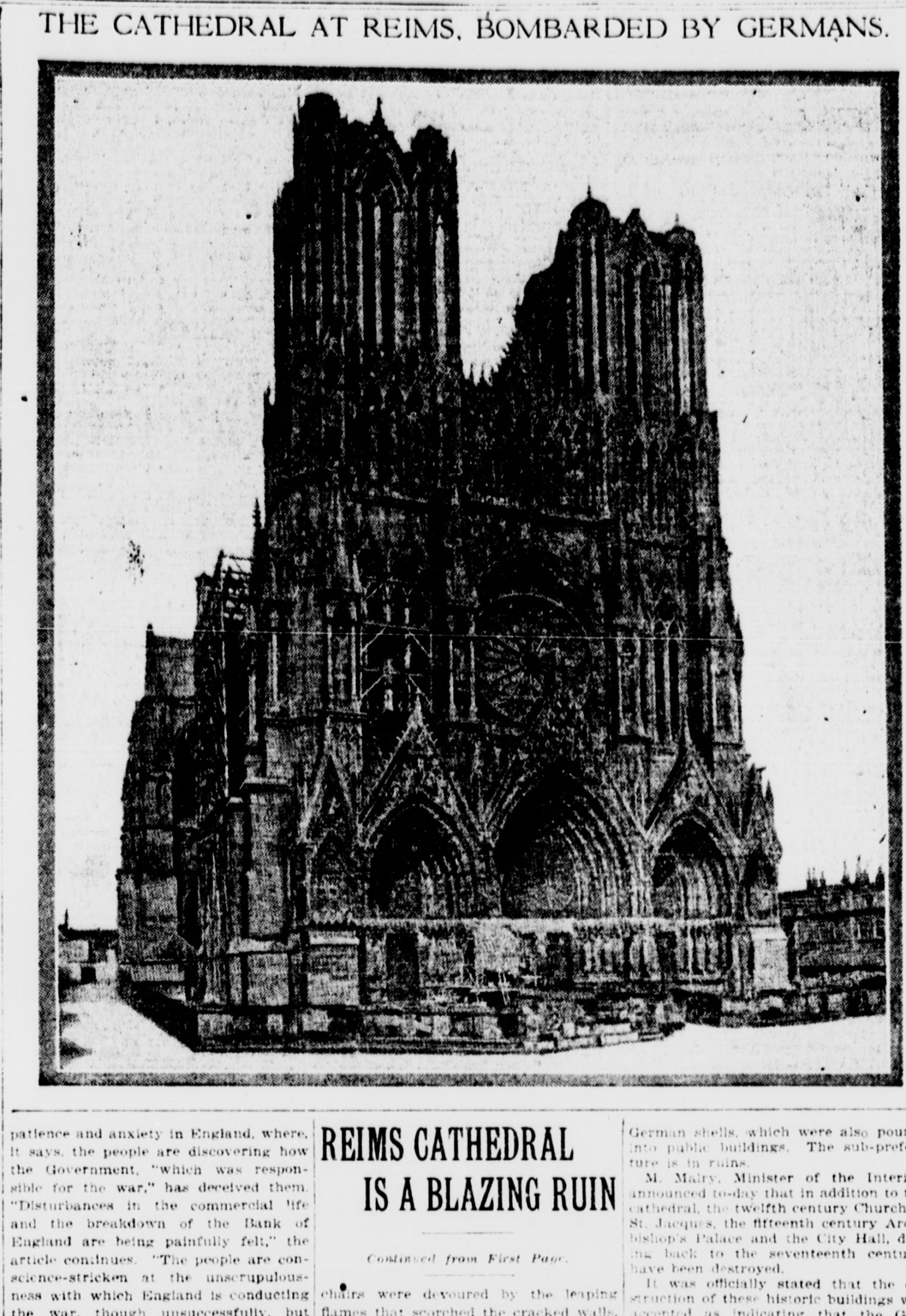

The city of Reims saw significant destruction, and both civilian and military casualties. But no event ignited indignation as did the bombing of the much-venerated Notre-Dame de Reims. The cathedral was first hit by shell fire on September 19th, 1914. Wooden scaffolding that was in place for ongoing repairs caught fire, and contributed to the damage, as did several smaller fires that resulted from the attack. Though the cathedral would be struck again and again as the war continued, it was this initial shelling that sparked a firestorm of outrage, horror, and prodigious propaganda—surely here was damning proof that the Germans were indeed “barbarians,” so lacking in culture themselves that they were compelled to destroy the beauty of another culture out of sheer spite and jealousy. The propaganda insisted that there was no reason to bomb the church since it had no strategic military value, and was a place of sanctuary. The French and their allies stressed that there was no justification to shell the cathedral especially given that was being used to house the wounded (mainly German soldiers callously left behind by their fleeing brothers-in-arms).

“Reims Cathedral is a Blazing Ruin,” The Sun (New York City), September 21, 1914 (Library of Congress)

War crimes

It was acknowledged, even at the time, that the Germans were committing more horrendous acts than the bombardment of Reims Cathedral. So why should a building create more outcry and indignation than the killing of innocent civilians, or other kinds of wartime savagery? Perhaps it was in part that the cathedral, literally meaning the seat of the bishop, could be seen as representing the French nation as a whole, its cruciform shape evoking a sacrificial body. Or, on a more practical note, it was a story that could be easily sensationalized and discussed ad infinitum—cultural war damage was far easier to get past the censors. In the words of Maurice Landrieux, a former priest at Reims but later the Bishop of Dijon “…but it was the most ignoble, because it was at once sacrilegious and stupid, and because it reveals, by its uselessness, the blackest depth of German misdoing.” There was a pervasive belief that the Germans had come to France with the express intention of destroying the cathedral from the outset of the war.

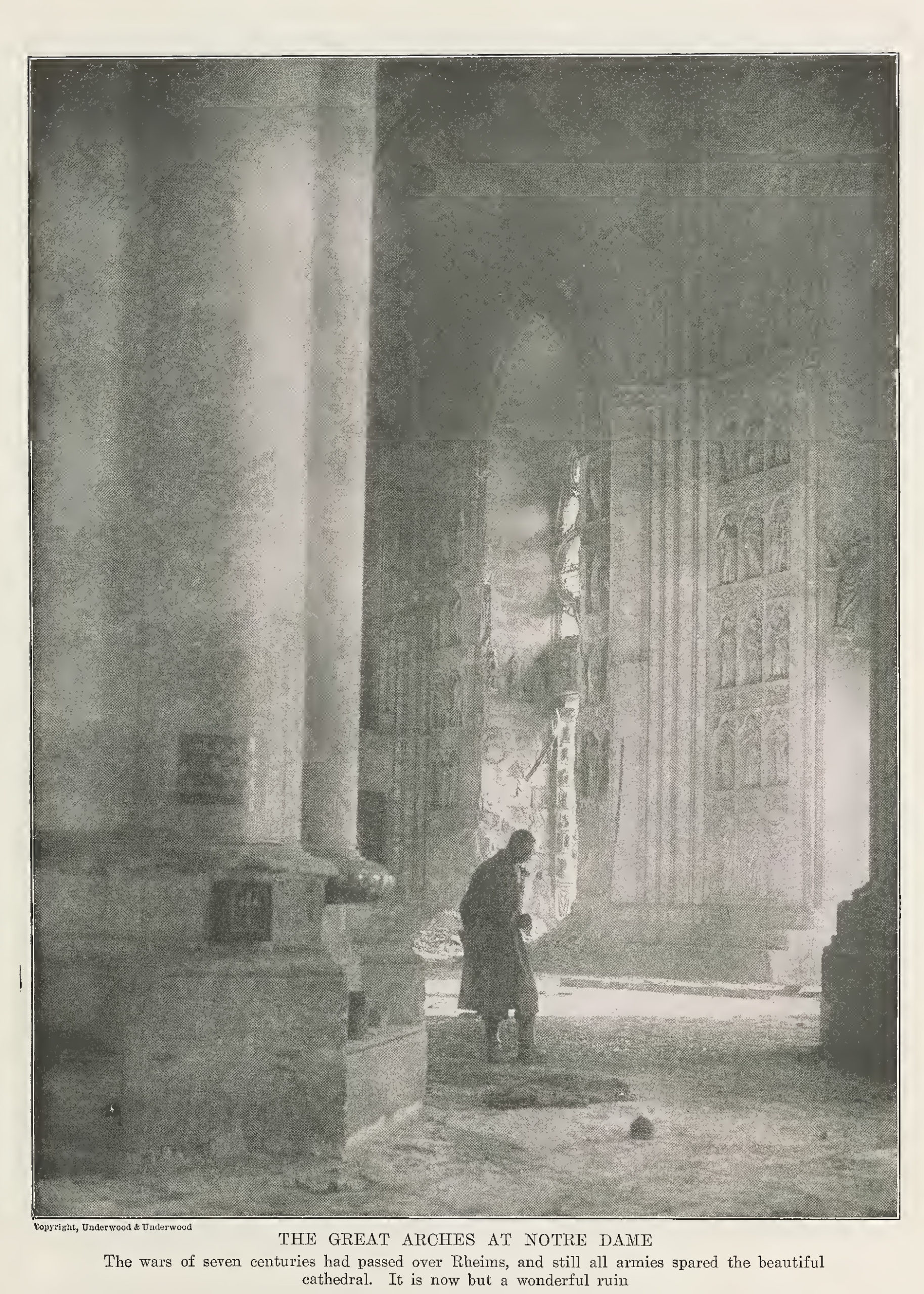

“The great arches at Notre Dame: The wars of seven centuries had passed over Reims, and still all armies spared the beautiful cathedral. Is is now but a wonderful ruin.” from Collier’s Photographic History of the European War, by Francis J. Reynolds and C. W. Taylor, c. 1917

There are two sides to every story, and so it is here. The Germans did shell the cathedral—that is irrefutable. Their explanation as to why they did so was wildly at odds with the French account, and they claimed to be horrified just as deeply as the French, at the damage done to this architectural masterpiece.

The French story was that is that the Germans, before their hasty retreat, had covered the floors of the cathedral with straw, to make it more combustible and that they intentionally left their wounded knowing they would be brought into the church by the French to be tended. A Red Cross flag was raised, a further signal that the cathedral was off-limits as a military target. However, the Germans later claimed the cathedral was being used for military intelligence: a signal station, telephone equipment, and an observation post had been espied in one of the towers during a German fly-by—along with a large cache of weapons. If true, according to international law, the cathedral was a viable military target—a wolf wrapped in sheep’s clothing.

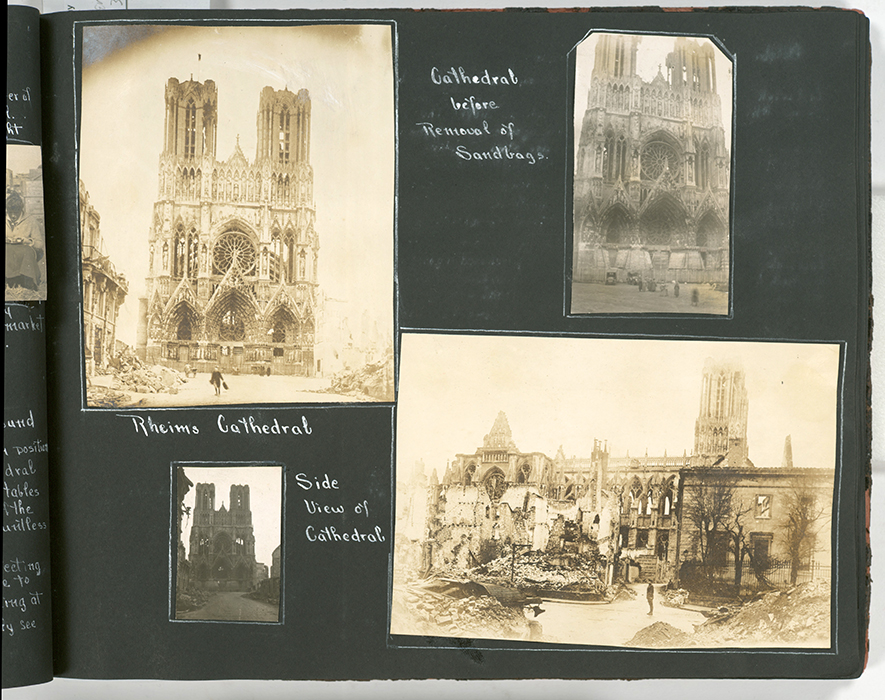

“Cathedral before removal of sandbags (upper right); Reims Cathedral; side view of cathedral” (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

The church was severely damaged—roofs had burned, statues melted, stonework was no longer viable, and more. Nonetheless, the structure was still essentially in good condition after the attack, all things considered. The local French authorities were actually taken to task by their own administrators for not doing a better job putting out the fire, which caused the majority of the damage. The Germans claimed it pained them to commit such an act, but the cunning French had left them no choice. These claims gained little traction.

The result was that—for the French—the German reputation for philosophical thought and general erudition, were suddenly erased—they were viewed once again as one of the “barbarian hordes” of the migration era. German art historians were quick to point out they had been one of the primogenitors of that discipline, and they highly appreciated art from around the globe. German art historians and professors were even dispatched to the front, joining various army units to help provide protection to valuable art on both sides, but to no avail. The mud would not unstick.

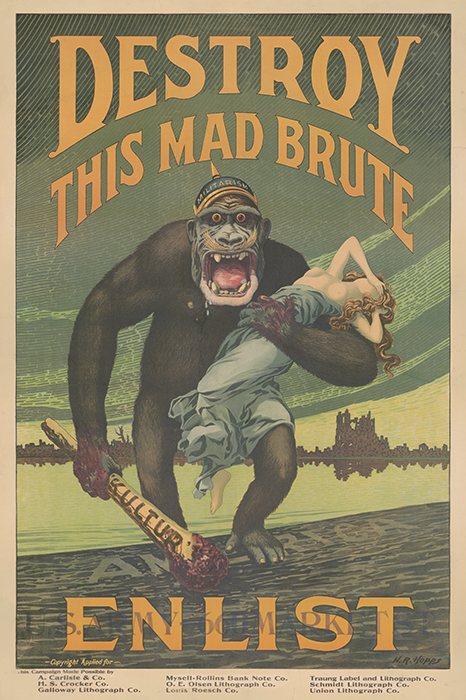

Harry R. Hopps, Destroy this mad brute Enlist – U.S. Army, 1918, color lithograph, 106 x 71 cm (Library of Congress)

Culture wars

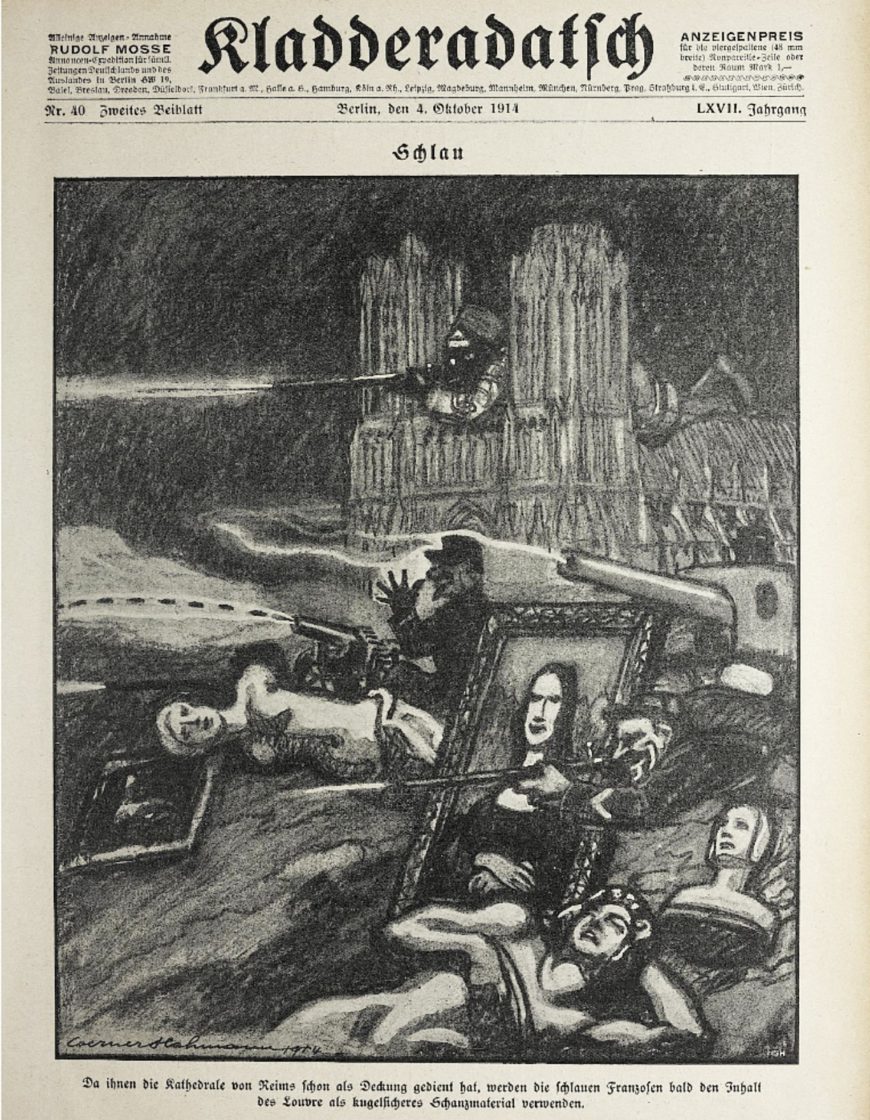

Reims Cathedral continued to be used as propaganda for the whole of the war. Its burnt image was printed on posters and postcards. German soldiers were depicted gun-wielding and slavering at the jaw to seeking to destroy the next great work of art they saw. Meanwhile, the Germans lampooned the French, accusing them of using their own great works of art for nefarious ends without compunction. One well-known cartoon read, “The cunning French have used Reims cathedral as a shooting platform—next they’ll be building trenches with the contents of the Louvre.”

“The cunning French have used Reims cathedral as a shooting platform—next they’ll be building trenches with the contents of the Louvre,” Werner Hahmann, Schlau (Sly), from Kladderarsch, no. 40 (cover, October 1914)

Beyond the trenches, the battle for cultural superiority was on. The French had the upper hand when it came to the events at Reims that fateful night. They could claim eyewitnesses, and they also photographed the cathedral in ways intended to most incite a viewer.

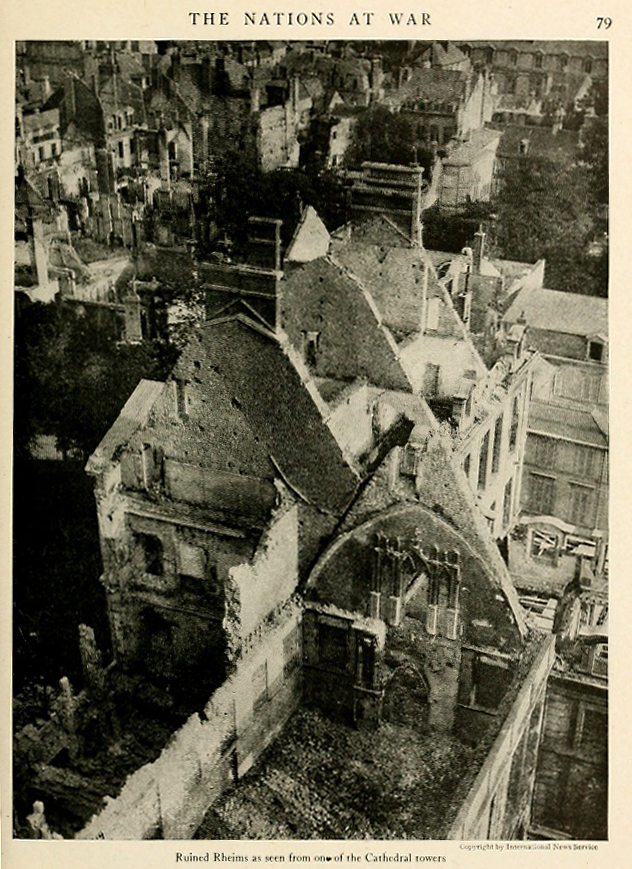

“Ruined Reims as seen from one of the Cathedral towers,” from The Nations at War by Willis John Abbot, 1917

The Germans did try hard though, despite their lack of handy visual evidence, to underscore that they had been the only country to carry out any form of art protection. Kunstschutz (the German term for the principle of preserving cultural heritage and artworks during armed conflict) was said to protect art on both sides of the war. It was even said to be endorsed by Kaiser Wilhelm II himself. The Germans emphasized that the bombing of the cathedral at Reims had not been part of a systematic effort, instead, it was one of the many sad byproducts of the war.

E. Lemielle, Souvenez-vous! 1914. Rien d’Allemand!!! Des Allemands (Remember! 1914. Nothing German! Nothing from the Germans), 1919, color lithograph, 83 x 60 cm (Library of Congress)

Neither side held back, each was determined to show that while one was on the side of the angels, the other was ruthlessly attempting to profit by the destruction of art. Meanwhile, the Germans claimed that as they were the creators of the Gothic style, and so the cathedral was just as much part of their cultural heritage as it was France’s, and they again attempted to remind the world of their integral role in the creation of art history. Again, this gained no traction with the French, nor with most nations.

“The cathedral of Notre Dame at Reims, after repeated bombardments,” from Collier’s Photographic History of the European War, by Francis J. Reynolds and C. W. Taylor (c. 1917)

By the end of the war Reims, which had been targeted multiple times, was the ruin the French had claimed after the initial attack. The continued attacks on the cathedral called into doubt the veracity of the Germans’ initial account. After the first bombardment, it was certain that the cathedral was no longer being used for any military purpose—if it ever had been. Again, a cultural landmark of this kind could only become subject to brute force with good reason, so the continued bombing only furthered the French position of German brutality and outright vandalism. J.W. Garner, in his International Law and the World War, states, “Monuments of this stature are not only entitled to respect because of their sanctity but are especially protected because of the Law of Nations” (p. 445).

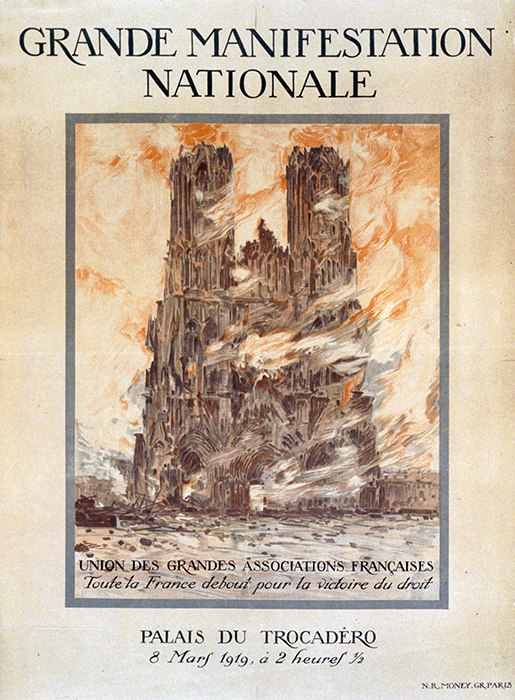

Grande Manifestation Nationale, 1919, color lithograph, 80 x 59 cm (Library of Congress)

Restoration on the cathedral began almost immediately after the end of the war, funded in part by the Rockefeller family. The cathedral reopened in 1938, though work continues to this day. Recently, the world looked on aghast when, in April of 2019, the iconic Notre-Dame de Paris burned. Even more recently, the lesser-known Cathedral of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in Nantes, another Gothic jewel, caught on fire. In these cases there appears to be no terrorism involved, only age and human error. Perhaps then, the most important take-away from the bombing of Reims Cathedral is that blame is, to a degree, irrelevant, at least after the fact. The real lesson is that we must do better at preserving our cultural heritage the world over.

Marc Chagall, stained glass windows replacing war-damaged ones, Reims Cathedral, 1967-1985 (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris, Dr. Steven Zucker and Christine M. Bolli, “Reims Cathedral,” in Smarthistory, April 25, 2017, accessed June 5, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/reims-cathedral/.

Amiens Cathedral

Robert de Luzarches, Thomas de Cormont, and Renaud de Cormont, Amiens Cathedral, Amiens, France, begun 1220; speakers are Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

View of Amiens Cathedral from the south-east, begun 1220 (photo: BB 22385, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Visiting Amiens Cathedral

With its two soaring towers and three large portals filled with sculpture, Amiens Cathedral crowns the northern French city of Amiens. The cathedral is still one of the tallest structures in the city, its spire climbing nearly 400 feet into the air. You can see the skeletal stone structure on the exterior of the church, where flying buttresses support the upper walls like spider legs or a ribcage. The lace-like façade is made up of slender colonnettes and screen-like openings, heightening the contrast of light and shadow. Deeply set portals topped with tall gables pull the viewer in, an invitation to approach the building and cross the threshold.

Flying buttresses highlighted in red, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Portal Sculpture

Through a series of intertwined images, each portal tells a story important to the Christian Church and the local Christian community through its stately sculpture. Within these portals, there is a whole sculpted universe to discover, with a multitude of figures, creatures, and narrative scenes, large and small. Some art historians have called this façade a sermon wrought in stone. If you visit the right portal, you will see images from the life of the Virgin Mary; in the left portal, you’ll find the story of Saint Firmin, the first bishop of Amiens, and images of local saints. Let’s take a closer look at the central portal.

Portals, West façade, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Beau Dieu, or beautiful God

The central portal announces its importance through its emphasized height and width. This is where you will find the trumeau figure of Christ—the Beau Dieu, or beautiful God—surrounded by the twelve apostles. You’ll notice that the figures on the portal at Amiens are sculpted with a high degree of realism, and that their heavy drapery hangs in languid folds on the figures’ bodies.

Trumeau, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Beau Dieu, Trumeau, west façade, Amiens Cathedral

The Beau Dieu looks out onto visitors to the cathedral with an expression of peace, holding one hand in a gesture of blessing and a book in the other, signifying the importance of the biblical text. Originally, this figure and the rest of the portal sculpture would have been painted in dazzling colors, enhancing their lifelike qualities. Some of this polychromy remains along the hem of the Beau Dieu’s garment and in the outward gaze of the eyes.

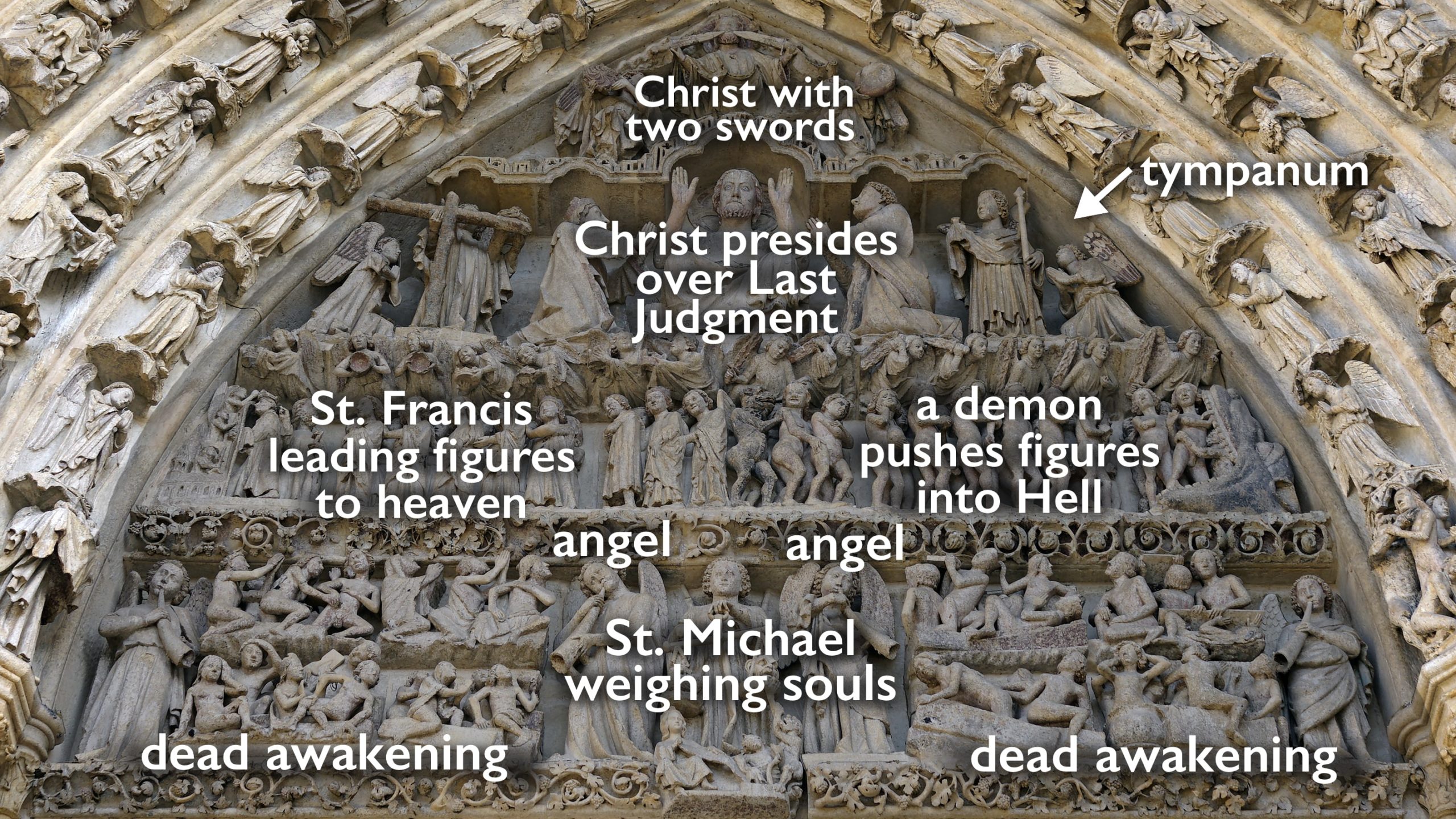

Tympanum

Above the trumeau, the tympanum depicts two more images of Christ. One version of Christ appears seated between kneeling figures of the Virgin Mary and St. John. He presides over the Last Judgment, a biblical event described in the last book of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation, in which the dead are awakened and sorted into Heaven and Hell.

On the lowest register of the tympanum, we see figures awakening from their tombs while St. Michael, flanked by trumpeting angels, weighs the souls of the dead. Above this register on the left, St. Francis leads a line of figures clothed in long robes into Heaven, where they are welcomed by St. Peter. On the right side of this register, a demon pushes a line of terrified, naked figures into the jaws of Hell. At the very top of the tympanum, a third image of Christ flies above the whole scene with two swords coming out of his mouth, a representation of the Christ of the Apocalypse, described in the Book of Revelation:

Coming out of his mouth is a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations. “He will rule them with an iron scepter.” He treads the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God Almighty. On his robe and on his thigh he has this name written: king of kings and lord of lords.Revelation 2:15

Courage (virtue) and fear (vice), west façade, Amiens Cathedral (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Virtues and vices

In addition to the three depictions of Christ, another set of images carved in relief appear at eye level: the Vices and Virtues. These quatrefoils are presented in pairs: Courage and Cowardice, Patience and Anger, Chastity and Lust.

The Virtues are represented by seated female figures holding shields, while narrative scenes depict the Vices. In the example illustrated here, the vice of cowardice is represented on the bottom as a knight so frightened by a small rabbit that he jumps away and drops his sword. Above, is the virtue of courage represented by a seated figure holding a shield with the image of a lion.

These images suggest to the viewer that they, too, can choose to follow a life of virtue, rather than a life of vice. By following this prescription, he or she can work towards an afterlife in the kingdom of Heaven, like St. Francis, and avoid the jaws of Hell.

Nave looking east toward the altar, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220

Interior plan

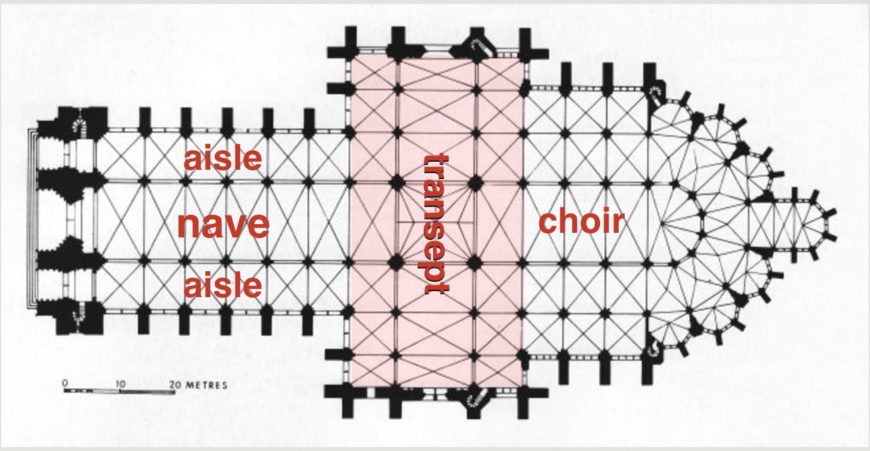

When you enter the cathedral (the entrance is on the west side), you might notice that the interior space is organized into three main aisles: a tall central aisle, called the nave, flanked by narrower aisles on either side. The church is laid out in a Latin cross plan, with a transept that intersects the nave and defines the choir.

Interior elevation

If you look up, you’ll see that the building is made up of three levels: the arcade, the triforium, and the clerestory of tall windows. The large piers that support the main arcade are over six feet in diameter, supporting a series of pointed arches crowned with quadripartite ribbed groin vaults.

Just below the triforium, you might notice the sculpted foliate band that runs the entire length of the cathedral. This feature is unique to Amiens; no other Gothic cathedral from this period has comparable foliate carving as elaborate or monumental in scale. The foliate band is made up of hundreds of individually sculpted blocks that fit together to create a seamless line of foliage—though if you look closely, you’ll see subtle differences throughout the building. The foliate carving in the nave is robust, while the transepts have less emphasis on the fleshy leaves. In the choir, the pattern changes altogether. The three modes of foliate carving correspond roughly to the three phases of construction carried out by three separate architects.

Clerestory in the nave (flying buttresses visible through the windows), Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Little remains of the original stained glass in the clerestory, which has been replaced with clear windows. Originally, light coming into the cathedral would have been filtered through the saturated jewel tones of colored glass. The medieval stained glass was removed before World War I as a precaution, but most of it was destroyed in a fire while in storage. The clear glass was installed later in the 20th century, incorporating fragments of medieval glass that survived. Some of the original panels can be seen in the choir triforium and rose windows.

Labyrinth, Amiens Cathedral, installed 1288

Center of the Labyrinth, Amiens Cathedral, installed 1288. The original plaque is in the Musée de Picardie.

Labyrinth

Amiens Cathedral is not only one of the most important examples of Gothic architecture from the medieval period, it is an experiential work of art signed by its makers. At the center of a large labyrinth, we find a plaque that depicts four men: the bishop Evrard de Foulloy, under whose leadership the cathedral’s construction began, and three architects: Robert de Luzarches, Thomas de Cormont, and Thomas’s son, Renaud. It is unusual that we know the names of these medieval master masons, as few building records from this time survive. These architects directed the construction of the cathedral beginning in 1220 until the installation of the labyrinth pavement in 1288 (today’s pavement, a faithful replica of the original, was replaced in the 1880s). Even though work continued after 1288, much of what we see today is the creation of these architects and their teams of sculptors and stonecutters.

Glass behind the triforium in the choir, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Changes to the building’s design

You can notice changes in the building’s design as you compare work in the nave and transepts with the architecture in the choir. The last architect, Renaud de Cormont, made some departures from his father’s design, including installing stained glass behind the triforium instead of opting for a solid wall, changing the decorative sculpture in the capitals, and altering the design of the foliate band.

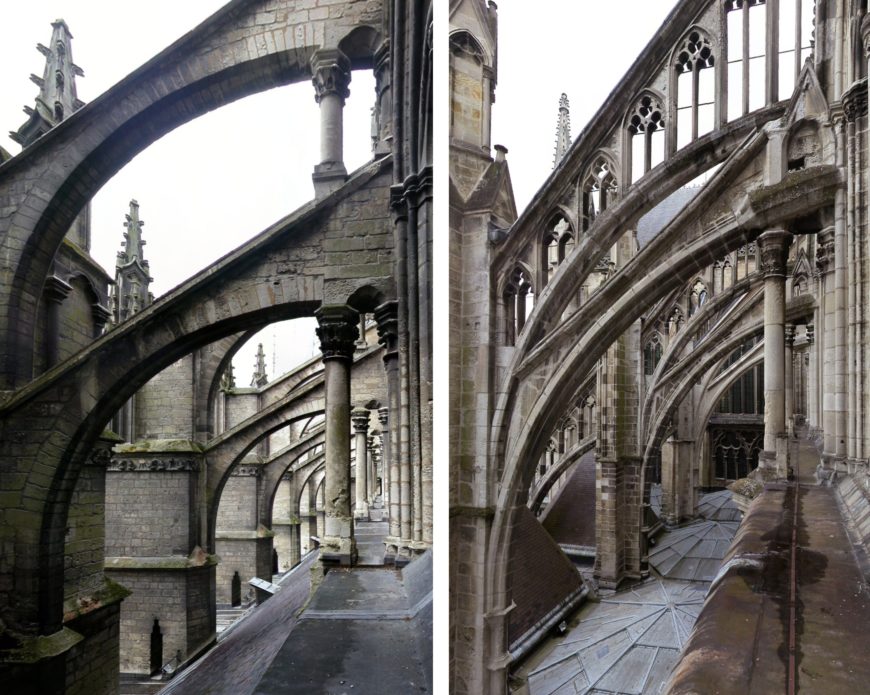

Unfortunately, some of these changes also led to structural instability in this part of the building. Just before 1500, one of the vaults suffered a partial collapse. The building had to be reinforced by an iron chain (still hidden inside the triforium today), and additional flying buttresses on the exterior.

On the exterior of this part of the building, we also see a difference in the flying buttresses: whereas the flying buttresses in the nave are solid, Renaud chose to use lace-like patterns in the openwork flying buttresses in the choir.

Left: nave flying buttresses; right: choir flying buttresses, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220

Why did Renaud do this? Art historians don’t have a definitive answer, but it is possible that the architect was responding to trends in Gothic design opting for more light, thinner supports, and more decorative qualities. Whatever the intention, the aesthetic effect is one of extraordinary delicacy.

View to the choir, Amiens Cathedral, begin 1220

In the choir, the architecture appears to float, as if the vaults were suspended above with little to support them. The added stained glass in the triforium would have filled this important part of the building—where the canons performed the mass in front of the high altar—with an ethereal light of dazzling color.

Through its architecture, sculpture, and history, Amiens Cathedral provides a window into the practice and culture of religious belief of the Middle Ages, as well as the ingenuity of medieval architects, masons, and artisans. This building stands as an irreplaceable example of the many dynamic forces at work in Gothic architecture.

Cite this page as: Dr. Emogene Cataldo, “Amiens Cathedral,” in Smarthistory, March 18, 2021, accessed June 5, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/amiens/.

Sainte-Chapelle

Louis IX’s patronage of the arts drove much innovation in Gothic art and architecture, exemplified by his commission of La Saint-Chappelle, an example of Rayonnant Gothic architecture.

Louis IX ruled during the so-called “golden century of Saint Louis,” when the Kingdom of France was at its height of power in Europe, both politically and economically. The king of France was regarded as a primus inter pares among the kings and rulers of the continent. He commanded the largest army, and ruled the largest and most wealthy kingdom of Europe, which was the European center of arts and intellectual thought (La Sorbonne) at the time. The prestige and respect for King Louis IX resulted more from his benevolent personality than from his military domination. For his contemporaries, he was the quintessential example of the Christian prince, and embodied the whole of Christendom in his person. The King was later recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church.

The style of Louis’ court radiated throughout Europe through the purchase of art objects from Parisian masters for export and by the marriage of the King’s daughters and female relatives to foreign husbands. Louis’ personal chapel, La Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, was copied more than once by his descendants elsewhere.

Gothic style as was King Louis IX’s personal chapel.

La Sainte-Chapelle (The Holy Chapel) is one of the only surviving buildings of the Capetian royal palace on the Île de la Cité in the heart of Paris, France. It was commissioned by King Louis IX of France to house his collection of relics of the passion, including the Crown of Thorns—one of the most important relics in medieval Christendom. Begun some time after 1239 and consecrated on April 26, 1248, the Sainte-Chapelle is considered among the highest achievements of the Rayonnant period of Gothic architecture . Although damaged during the French revolution and heavily restored in the 19th century, it retains one of the most extensive in-situ collections (collections that are still in their original positions) of 13th century stained glass anywhere in the world. The glass depicts stories from the Old Testament and focuses heavily on the depictions of biblical kings, both good and bad. Scholars believe the inclusion of “bad” kings, along with the good, were meant as a lesson for the royal viewer to learn from both good and bad examples of rulership.

La Sainte-Chapelle is a prime example of the phase of Gothic architectural style called “Rayonnant

Cathedrals that came before them. La Sainte-Chapelle stands squarely upon a lower chapel, which served as parish church for all the inhabitants of the palace, which was the seat of government. However, the chapel proper was a private royal chapel and scholars have noted how the structure almost looks like metalwork , as if the chapel itself is a reliquary.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Sainte-Chapelle, Paris

Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Sainte-Chapelle, Paris,” in Smarthistory, May 24, 2017, accessed June 5, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/sainte-chapelle-paris/.

Salisbury Cathedral (England)

Salisbury Cathedral (England)

Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The biggest and the highest

There are so many superlatives consorting with the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Salisbury: it has the tallest spire in Britain (404 feet); it houses the best preserved of the four surviving original copies of the Magna Carta (1215); it has the oldest working clock in Europe (1386); it has the largest cathedral cloisters and cathedral close (grounds) in Britain; the choir (or quire) stalls are the largest and earliest complete set in Britain; the vault is the highest in Britain. Bigger, better, best—and built in a mere 38 years, roughly from 1220 to 1258, which is a pretty short construction schedule for a large stone building made without motorized equipment.

One factor that enabled Salisbury Cathedral to become so extraordinary is that it was the first major cathedral to be built on an unobstructed site. The architect and clerics were able to conceive a design and lay it out exactly as they wanted. Construction was carried out in one campaign, giving the complex a cohesive motif and singular identity. The cloisters were started as a purely decorative feature only five years after the cathedral building was completed, with shapes, patterns, and materials that copy those of the cathedral interior.

Looking west from the choir to the nave, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Nave elevation, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

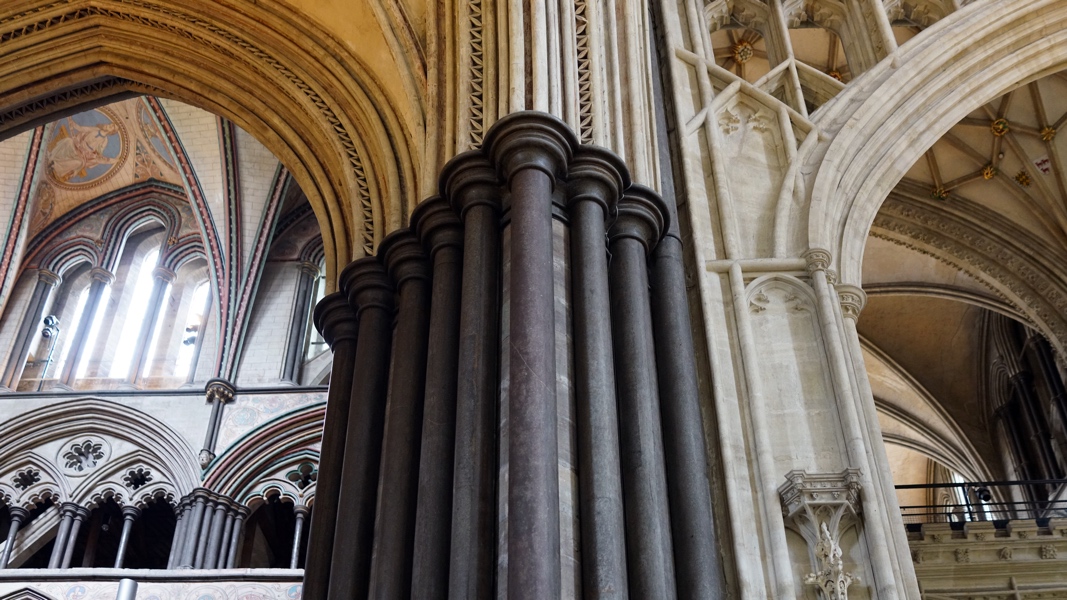

It was an ideal opportunity in the development of Early English Gothic architecture, and Salisbury Cathedral made full use of the new techniques of this emerging style. Pointed arches and lancet shapes are everywhere, from the prominent west windows to the painted arches of the east end. The narrow piers of the cathedral were made of cut stone rather than rubble-filled drums, as in earlier buildings, which changed the method of distributing the structure’s weight and allowed for more light in the interior.

The piers are decorated with slender columns of dark gray Purbeck marble, which reappear in clusters and as stand-alone supports in the arches of the gallery, clerestory, and cloisters. The gallery and cloisters repeat the same patterns of plate tracery—basically stone cut-out shapes—of quatrefoils, cinquefoils, even hexafoils and octofoils. Proportions are uniform throughout.

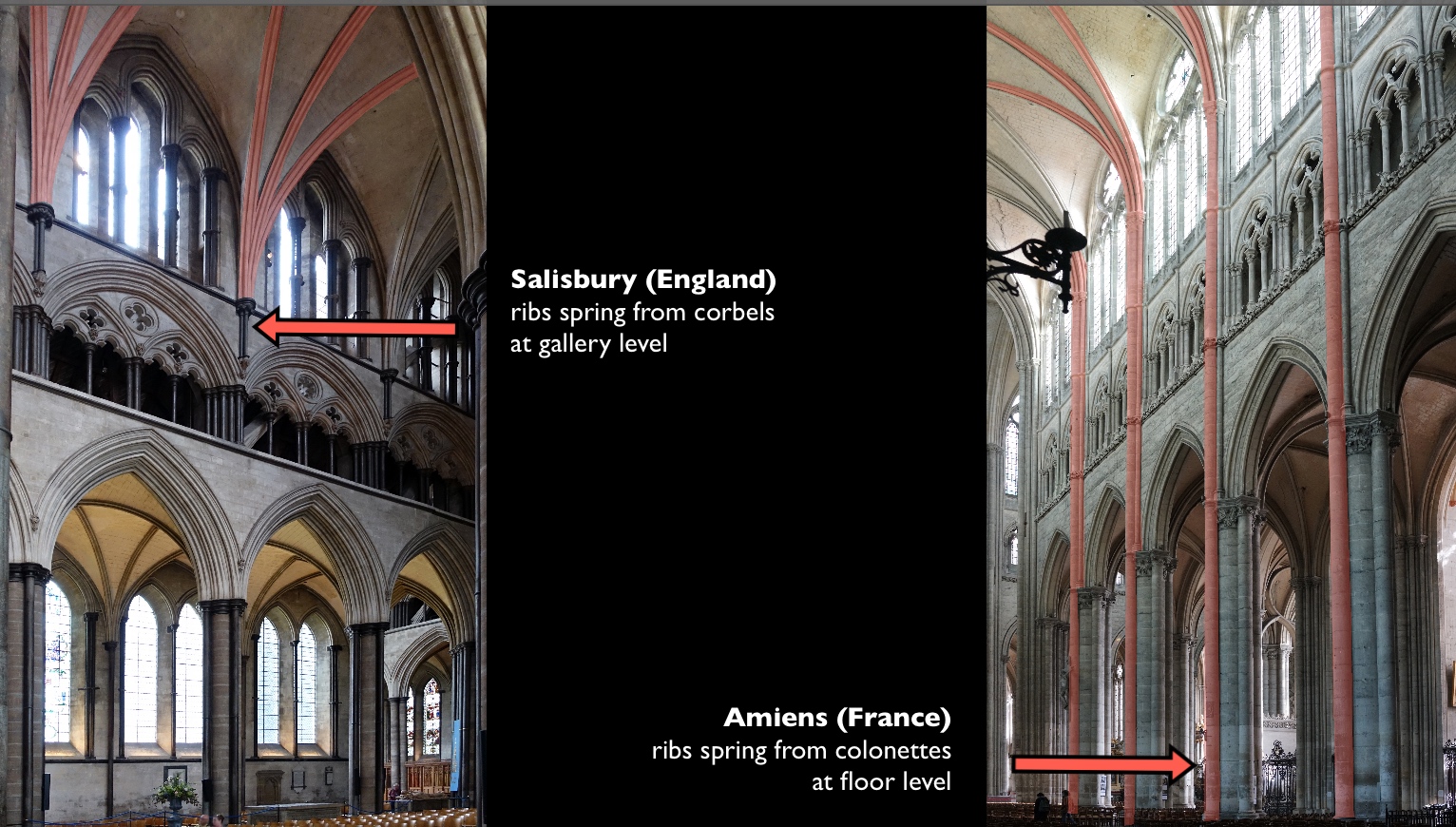

One deviation from the typical Gothic style is the way the lower arcade level of the nave is cut off by a string course that runs between it and the gallery. In most churches of this period, the columns or piers stretch upwards in one form or another all the way to the ceiling or vault (see diagram below). Here at Salisbury the arcade is merely an arcade, and the effect is more like a layer cake with the upper tiers sitting on top of rather than extending from the lower level.

Comparison of the nave elevations of Salisbury Cathedral and Amiens Cathedral Nave elevation, photos: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The tower and the spire

The original design called for a fairly ordinary square crossing tower of modest height. But in the early part of the 14th century, two stories were added to the tower, and then the pointed spire was added in 1330. The spire is the most readily identified feature of the cathedral and is visible for miles. However, the addition of this landmark tower and spire added over 6,000 tons of weight to the supporting structure. Because the building had not been engineered to carry the extra weight, additional buttressing was required internally and externally. The transepts now sport masonry girders, or strainer arches, to support the weight. Not surprisingly, the spire has never been straight and now tilts to the southeast by about 27 inches.

Scissor (strainer) arches in the east transept, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Restorations

Over the centuries the cathedral has been subject to well-intentioned, but heavy-handed restorations by later architects such as James Wyatt and Sir George Gilbert Scott, who tried to conform the building to contemporary tastes. Therefore, the interior has lost some of its original decoration and furnishings, including stained glass and small chapels, and new things have been added. This is pretty typical, though, of a building that is several centuries old. Fortunately, the regularity and clean lines of the cathedral have not been tampered with. It is still refined, polished, and generally easy on the eye.

Purbeck colonettes at the crossing (transept), and to the left, gallery and clerestory moldings that have been repainted, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Sunlight

Although it inspires the usual awe felt in such a grand and substantial building, and is as pretty as a wedding cake, it has had some criticism from art historians: Nikolaus Pevsner and Harry Batsford both disliked the west front, with its encrustation of statues and “variegated pettiness” (Batsford). John Ruskin, the Victorian art critic and writer, found the building “profound and gloomy.” Indeed, in gray weather, the monochromatic scheme of Chilmark stone and Purbeck marble is just gray upon gray.

The pictures, however, show the widely changing character of the neutral tones; sunlight transforms the building, and the visitor’s experience of it. This very quality is what made the Gothic style so revolutionary—the ability to get sunlight into a large building with massive stone walls. Windows are everywhere, and when the light streams through the clerestory arches and the enormous west window, the interior turns from drear gray to transcendent gold.

Cite this page as: Valerie Spanswick, Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Salisbury Cathedral,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed June 5, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/salisbury-cathedral/.

A grand entrance, door, or gateway, typically leading into a significant public building. It is often adorned with sculpture.

A triangular space between the sides of a pediment; the space within an arch and above a lintel or a subordinate arch, spanning the opening below the arch.