Entrance into the Rajarajesvara (sometimes spelled Rajarajeshwara) temple complex, c. 1004–1010, Chola period, Tanjavur, Tamil Nadu (photo: KARTY, CC BY-SA 4.0)

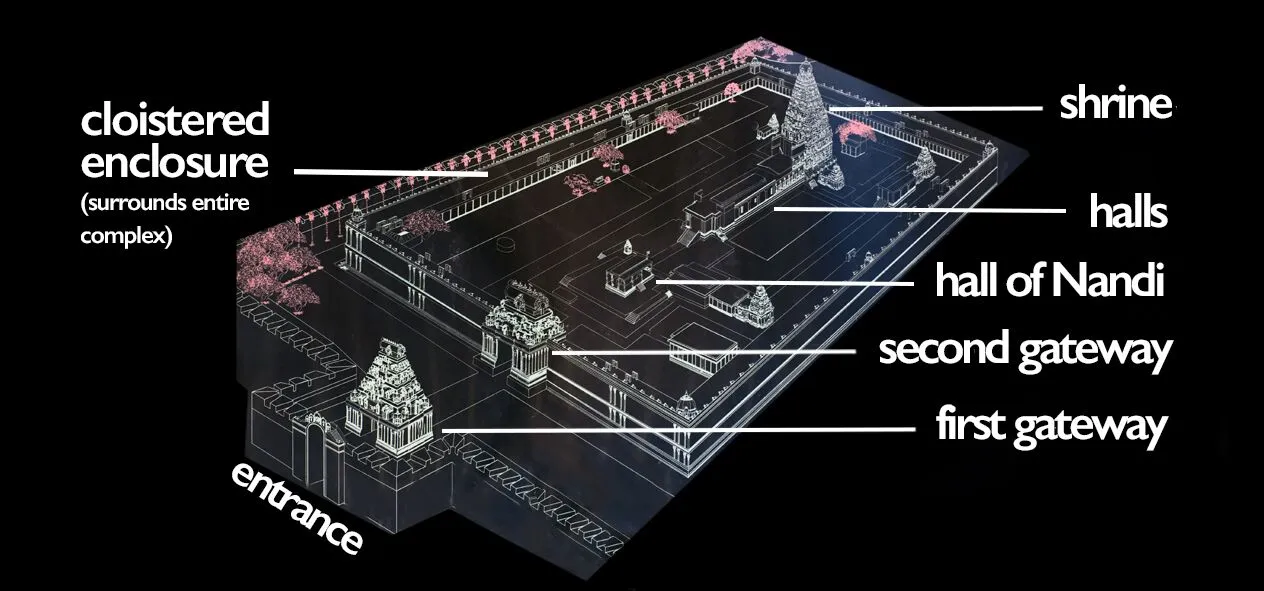

To see the Hindu god Shiva in the Rajarajesvara temple complex in Tanjavur, we must enter two impressive gateways, walk into a cloistered courtyard, past an enormous stone bull, climb the stairs of the largest temple, and proceed through halls filled with beautifully carved pillars. Then, straight ahead, at the far end of the interior of the temple is the monumental Shiva linga — an aniconic (non-representational) emblem of the deity. Above the linga, a tall superstructure rises, reaching a height of 216 feet from the ground. This is the symbolic core of the Rajarajesvara temple, the city of Tanjavur, and the Chola empire.

Rajarajesvara temple (south), c. 1004–1010, Chola period, Tanjavur, Tamil Nadu (photo: Emanuel DYAN, CC BY 2.0)

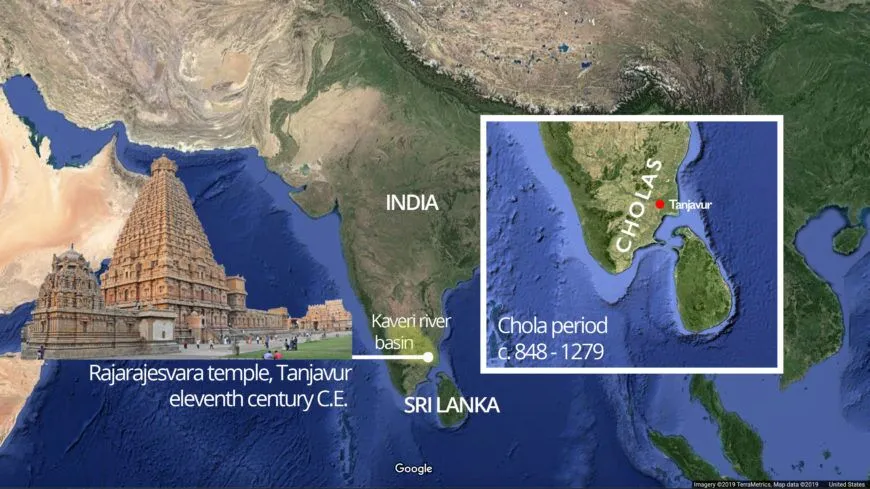

The Rajarajesvara temple was built by one of the most successful rulers of the medieval period, Rajaraja Chola I. Tanjavur was the capital of the Cholas, an empire that ruled much of present-day South India from c. 848 until 1279. Although this region had been home for the Cholas for generations — they are even mentioned in an Ashokan edict from the third century B.C.E. [1] — it is the family of Chola rulers who emerged in the ninth century who would leave an indelible mark on the history of art and architecture.

Location of Rajarajesvara temple in the Chola capital of Tanjavur. Inset shows Chola territory in South India

The Cholas’ prosperity was largely due to their investment in harnessing water in the Kaveri river basin for agricultural and irrigation projects and turning vast areas into cultivable land. This, alongside their increased commercial endeavors and active participation in Indian Ocean maritime trade contributed to a thriving empire.

Rajarajesvara temple is emblematic of the Cholas’ might and prosperity at the turn of the eleventh century. At that point Chola territory had expanded to include much of south India and parts of Sri Lanka. Chola influence also extended to Southeast Asia where they had established profitable commercial interests with the kingdom of Srivijaya in Indonesia.

Records in stone

The immense skill of the Rajarajesvara temple’s architect, builders, and sculptors is immediately apparent from the size and the grandeur of the temple. Also clearly evident is the significant amount of resources — people, time, and stone — that was involved.

The temple preserves records in the form of inscriptions that are carved on its stone base. The inscriptions provide a wealth of information; the gifts received by the temple in the form of jewelry, processional bronze images for use in ritual and festivals, and endowments given for the maintenance of temple activities are documented.

Inscriptions (in the Tamil language) on the base of Rajarajesvara temple, c. 1004–1010, Chola period, Tanjavur, Tamil Nadu (photo: KARTY, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Inscriptions also provide details on the conduct of rituals, the allocation of resources owned by the temple, and mention the names of donors. The temple received contributions from the king, queens, ministers and feudatories, as well as the temple’s priests and administrators.

Royal, sacred, and cultural center

The Rajarajesvara temple was located within a royal and sacred complex. The king’s palace, which was nearby, doesn’t survive. The temple’s impressive height (it was the largest of its kind at the time) and wealth must have impressed Tanjavur’s citizenry. The temple’s economic influence was considerable — many people tended the lands owned by the temple, and the temple employed hundreds as dancers, priests, accountants, and administrators. Rajarajesvara temple was also an influential cultural center with performances of dance and music, as well as a place of spiritual education and discourse.

Approximate difference in size between earlier regional temples (indicated by scaled temple on left) and Rajarajesvara temple. At 216 feet, Rajarajesvara temple is roughly fives times larger than earlier temples. (photo: Arian Zwegers, CC BY-2.0)

The Cholas were not new to temple building. Inscriptions on the walls of earlier temples tell us that the Chola queen Sembiyan Mahadevi was an enthusiastic temple builder. She even rebuilt older brick temples in stone, making sure that the inscriptions of those temples were re-inscribed on their rebuilt walls.

There was no comparable Chola antecedent for the monumental size of the Rajarajesvara temple (see its relative difference in scale from earlier temples in the image above). Rajarajesvara stands as testament to the unhesitating confidence of those who dreamed, conceptualized, and engineered the temple.

Plan of the Rajarajesvara temple complex (photo: Junykwilfred, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A grand entrance

Just past a moat, a large and impressive gopura (gateway) stands as the first entryway into the sacred complex (see plan above). A short walk reveals a second gopura with two massive guardian figures carved in high relief, flanking the entryway. Guardians are a common feature in Indian temple architecture. They are protective figures who safeguard portals to the gods and are often portrayed as intimidating. The guardian figures here are large, multi–armed and hold a mace (club) — attributes that highlight their role as divine guardians. The guardians are dynamic and animated; they are adorned with elaborate jewelry and clothing, have raised eyebrows and sharp fangs, and they rest an arm and a foot on their weapon as they stand confidently and at the ready to protect.

Guardian figure at the second gopura, Rajarajesvara temple, c. 1004–1010, Chola period, Tanjavur, Tamil Nadu (photo: Arathi Menon, CC BY-SA-NC 4.0)

The second gopura (gateway) is part of a tall cloister (covered walkway) that surrounds the temple enclosure. The gopura is adorned with relief carvings below the guardians and sculptures on the superstructure above. These are smaller in scale relative to the guardian figures.

View of the Nandi mandapa (hall of Nandi) and the two gopuram (gateways) from inside the temple enclosure (photo: Vbmindia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Within the enclosure, a large monolithic stone bull is dressed with jewelry and a necklace of bells. This is Nandi, Shiva’s vahana. He sits with his back to the gopura, facing the main temple structure (which houses Shiva). Nandi and the open pillared stone canopy over him are dated to the sixteenth century or later, although the platform upon which Nandi is seated may be earlier. As a living temple (a temple that is an active site for worship), Rajarajesvara continued to receive gifts (such as funds for a new Nandi and canopy) long after the temple’s construction.

Nandi, Rajarajesvara temple, c. 16th – 17th centuries, Nayak period, Tanjavur, Tamil Nadu (photo: Thamizhpparithi Maari, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Dravida style

There are multiple Indian temple architectural styles, the most common of which are dravida and nagara. The dravida style of temple architecture is more frequently adopted in south India, while temples in north India are more often built in the nagara style. Rajarajesvara is built in the dravida style.

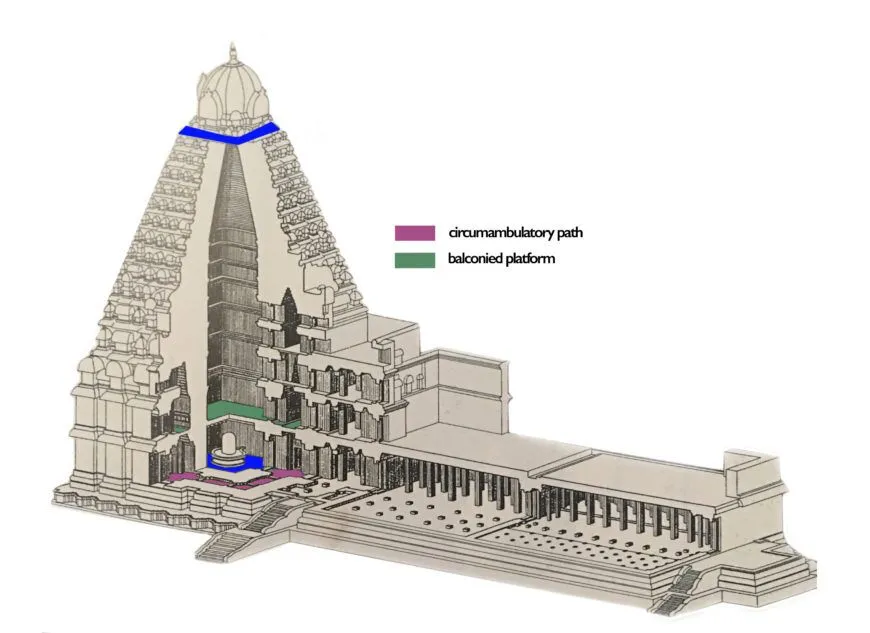

The main structure is comprised of the shrine and two pillared halls that are attached and arranged one following the other. The hall closer to the entrance of the structure is known as the mukhamandapa (front hall) and the hall nearest to the shrine is known as the mahamandapa (great hall). At the center of the shrine is the garbagriha (sanctum) — the chamber of god. Above the shrine is a pyramidal superstructure known as the vimana.

Annotated view of Rajarajesvara temple, c. 1004–1010, Chola period, Tanjavur, Tamil Nadu (photo: Arathi Menon, CC BY-SA-NC 4.0)

Larger than life-size images of Shiva within decorated niches and framing pilasters line the exterior walls of the shrine on two levels. In Hindu belief, gods have myriad manifestations; each form represents a particular purpose or legend, but always represents the one and the same supreme being. Doorways pierce the center of the rows of figures.

South wall of Rajarajesvara temple. Shiva as Tripurantaka marked in red; various forms of Shiva marked in green. Guardian figures flank the doorway at the center of the lower level. (photo: Arathi Menon, CC BY-SA-NC 4.0)

The images of Shiva on the lower level show the deity in a number of different embodiments. Six niches on the upper level depict Shiva as Tripurantaka — a form in which Shiva defeated the three cities of the asuras (malevolent adversaries of the gods). Art historian Vidya Dehejia has suggested that the emphatic repetition of Tripurantaka, although in different poses, was likely significant to Rajaraja and his identity as conqueror. [2]

The exterior wall of the two halls in front of the shrine differ in their sculptural program. Here we find pierced stone windows, gods in decorated niches and pilasters, and incomplete carvings. Common to the walls of both the shrine and the two halls are a pair of continuous architectural courses of yalis (mythical creatures) who serve both a decorative and apotropaic (protective) function.

The main entrance into the structure is at its east end (facing Nandi the bull). The entryway is reached via two flights of stairs – one each at the north and south ends of a platform. The pillars on that platform and the frontal stairs are later additions. [3] There are also two sets of stairs and entrances flanked by guardians at the north and south sides of the building closer to the shrine.

Shrine and superstructure

Surrounding the garbagriha (sanctum) at the center of the shrine (see the plan below) is a circumambulatory path with wall murals (painted with a wet lime-wash and mineral pigments) that celebrate the legends of Shiva. The ceiling of this circumambulatory path serves as the floor of a balconied platform above. Carved in low relief on the balcony’s railing are images of dancing Shiva. [4] From here, tapered and corbeled slabs of masonry lend support to the remaining upper levels of the hollow vimana. [5]

Isometric drawing adapted from Partha Mitter, Indian Art (Oxford, 2001), p. 59. Areas in blue indicate the identical size of the sanctum and the uppermost platform of the vimana.

The vimana is decorated in horizontal registers on the exterior and at its very top carries a crowning piece known as the stupi. Above the stupi stands the kalasha, a pot-shaped finial that is made from copper.

The monumental linga — roughly 12 feet tall, beautifully adorned with flowers and glistening from the gold and the light of oil lamps — is immediately awe-inspiring. Only priests can enter the sanctum; devotees stand just outside the sanctum for darshan (to see and be seen by god) and for puja.

Vimana, Rajajesvara temple complex, c. 1004–1010, Chola period, Tanjavur, Tamil Nadu (photo: Gayathriveluri, CC BY-SA 4.0)

New heights

The temple’s architect and builders would have followed the general rules prescribed in treatises for the design of the sacred complex and its sculptures. Treatises on art and architecture were developed over centuries of temple building and offered precise instructions on appropriate siting, layout, and measurements for temple construction and ornamentation. Even with that guidance, the enormity of this project will have made for a complex undertaking.

More than a thousand years since it was built, there is little doubt that Rajarajesvara temple holds an important place in the legacy of the Cholas. By building a temple so incredible, Rajaraja Chola I aptly epitomized both his triumphant reign as king and gratitude for his achievements. And he affirmed — for all to see — the religious benediction of Shiva at the heart of his empire.

[1] See the 2nd major rock edict of Ashoka, for example, in Romila Thapar, Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 251.

[2] Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon, 1997), p. 214–6.

[3] K.R. Srinivasan, “Middle Colanadu style, c. A.D. 1000–1078; Colas of Tanjavur: Phase II.” In Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture: South India Lower Dravidadesa, 200 B.C.– A.D. 1324, edited by Michael W. Meister (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983), p. 239.

[4] Dehejia, ibid., pp. 217-8.

[5] Srinivasan, ibid., pp. 238.

Cite this page as: Dr. Arathi Menon, “Rajarajesvara temple, Tanjavur,” in Smarthistory, May 8, 2020, accessed August 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/temple-tanjavur/.