Introduction to Ancient Egypt

Introduction to Ancient Egypt

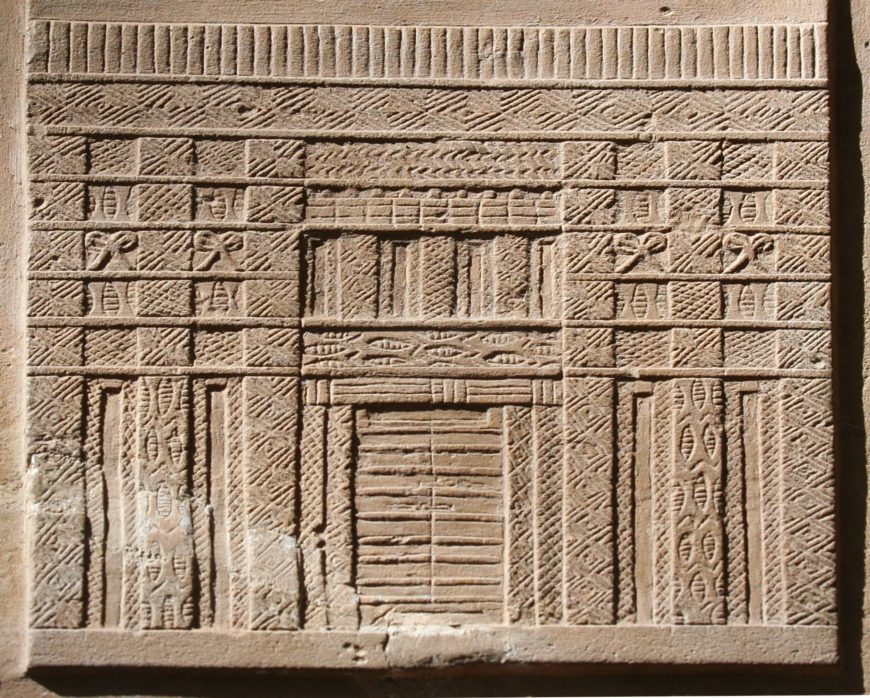

View of the South Court after leaving the entrance colonnade, Step Pyramid of Djoser, Old Kingdom, c. 2675–2625 B.C.E., Saqqara, Egypt (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Egypt’s impact on other cultures was undeniably immense. From the earliest periods of Predynastic Egypt, there is evidence of trade connections that extended as far east as the Indus Valley. These trade routes passed through the Near East, resulting in an early exchange of motifs and ideas between the civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. The New Kingdom brought even more active connections with Western Asia, including robust commercial and diplomatic relationships as well as a mutual exchange of imagery and concepts with cultures like the Assyrians and the Hittites. Lively interactions with the south contributed to dynamic cultures, such as the Kushites, who ruled Egypt during the 25th Dynasty and whose monuments displayed an innovative blend of local Nubian and pharaonic imagery.

Pyramids of Meroe, Northern Cemetery, Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe (Sudan) (photo: UNESCO, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

Rulers and the elite from Meroe, in modern Sudan, were buried in pyramid tombs for many centuries—with more than 200 having been identified, that country actually contains more pyramids within its borders than Egypt does. Egypt also provided some of the building blocks for the Aegean, Greek, and Roman cultures and, through them, influenced many aspects of Western tradition.

Today, Egyptian imagery, concepts, and perspectives are found everywhere; when you know what to look for, you will see them in architectural forms, on money, and in our day-to-day lives. Many cosmetic surgeons, for example, use the silhouette of Queen Nefertiti (whose name means “the beautiful one has come”) in their advertisements.

Longevity

Ancient Egyptian civilization lasted for more than 3,000 years and showed a stunning level of continuity. That is more than 15 times the age of the United States, and consider how often our culture shifts; as recently as 2003, there was no Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube.

While today we consider the Greco-Roman period to be in the distant past, it should be noted that Cleopatra VII’s reign is closer to our own time than it was to that of the construction of the pyramids of Giza. It took humans nearly 4,000 years to build something—anything—taller than the Great Pyramid. Contrast that span to modern times; we get excited when a record lasts longer than a decade.

Consistency and stability

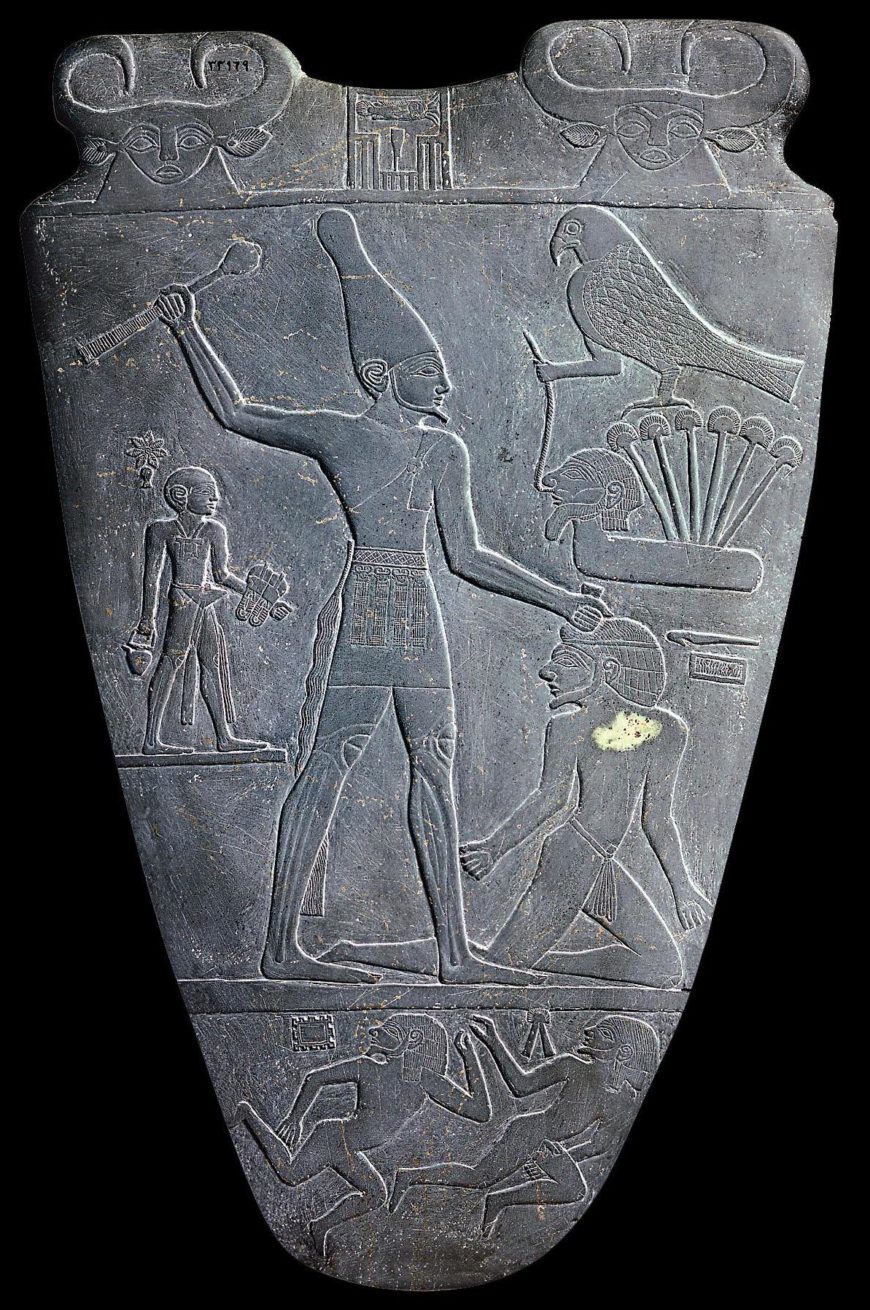

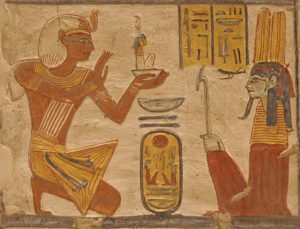

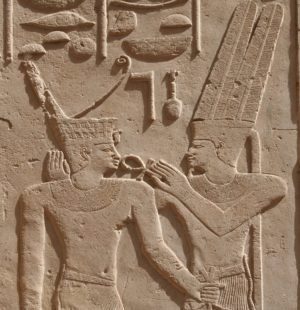

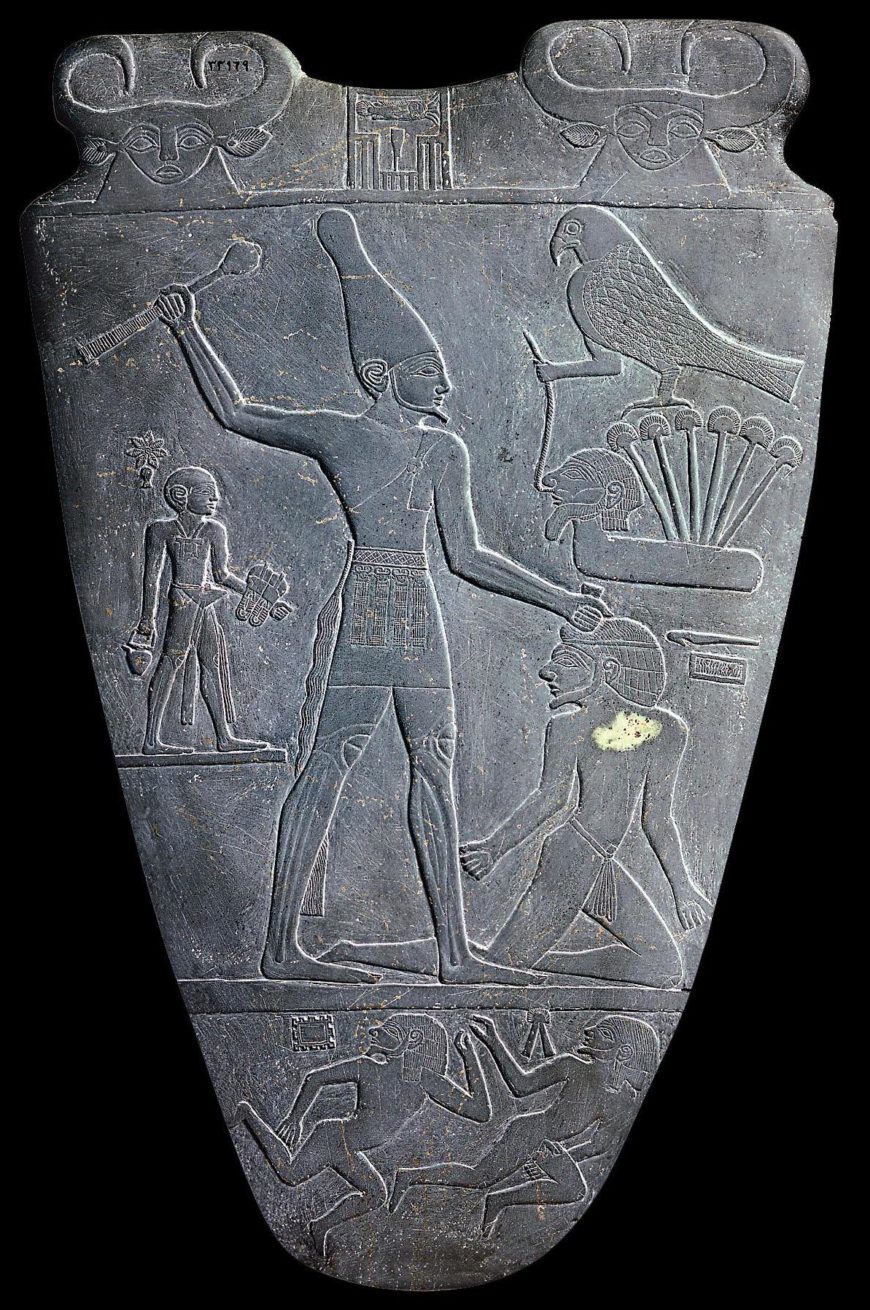

Egypt’s stability is in stark contrast to the Ancient Near East of the same period, which endured an overlapping series of cultures and upheavals with amazing regularity. The earliest royal monuments, such as the Narmer Palette carved around 3100 B.C.E., display identical royal costumes and poses as those seen on later rulers, even Ptolemaic kings and Roman emperors on their temples more than three millennia later.

This consistency and stability is closely linked with one of the central foundational concepts in the way ancient Egyptians saw the world around them. In their view, creation occurred when order triumphed over chaos and harnessed that amorphous power to bring the land of Egypt into existence. The perfect cosmic balance that resulted created the consistent cycles they saw in their natural world, such as the daily rising and setting of the sun and the Nile’s annual inundation. This divine order was known as ma’at—embodying truth, righteousness, justice, and cosmic law—and was eventually personified as a goddess. There was a perpetual struggle between ma’at and the chaos, known as isfet. From early in Egypt’s history, a primary role of the pharaoh was to be the champion of ma’at and preserve that cosmic order to help protect Egypt from the isfet that surrounded them. The ongoing preservation of ma’at was seen as fundamentally important and the drive to maintain that perfect cosmic balance permeated the culture on multiple levels.

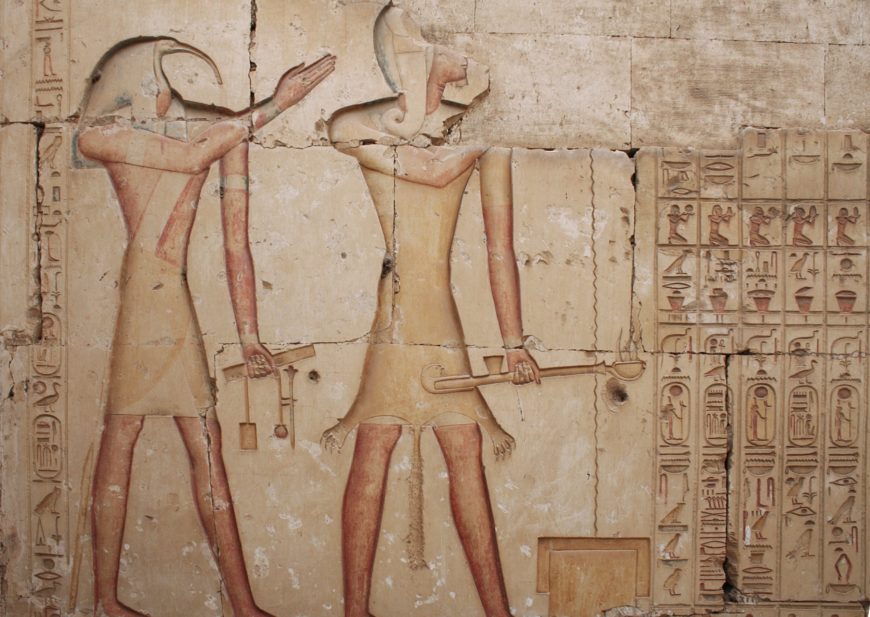

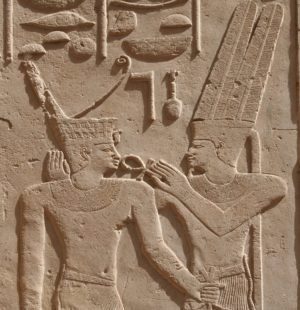

A vast amount of Egyptian imagery, especially royal imagery that was governed by decorum (a sense of what was ‘appropriate’), remained extraordinarily consistent throughout its history. This is why, especially to the untrained eye, their art appears extremely static—and in terms of symbols, gestures, and the way the body is rendered, it was. It was intentional, as the consistency was the whole point. The Egyptians were well aware of their consistency, which they viewed as stability, divine balance, and clear evidence of ma’at and the correctness of their culture.

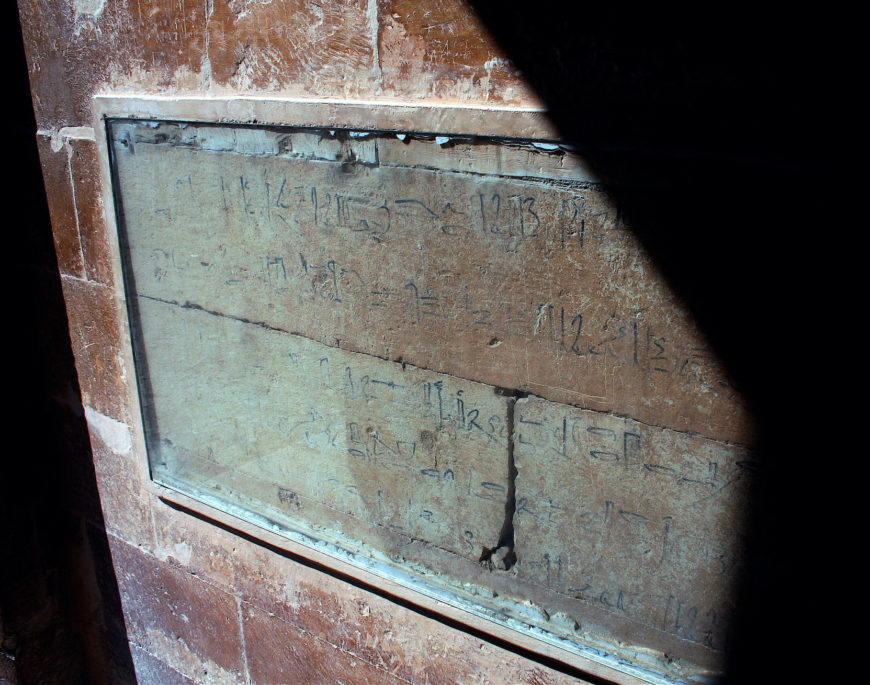

New Kingdom graffiti inside Step Pyramid complex (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

This consistency was also closely related to a fundamental belief that depictions had an impact beyond the image itself—tomb scenes of the deceased receiving food or temple scenes of the king performing perfect rituals for the gods were functionally causing those things to occur in the divine realm. If the image of the bread loaf was omitted from the deceased’s table, they had no bread in the afterlife; if the king was depicted with the incorrect ritual implement, the ritual was incorrect and could have dire consequences. This belief led to active resistance to change in codified depictions.

The earliest recorded “tourist graffiti” on the planet came from a visitor from the time of Ramses II, who left their appreciative mark at the already 1300-year-old site of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, the earliest of the massive royal stone monuments. They were understandably impressed by the works of their ancestors and wrote of their desire to continue that ancient legacy.

Ancient Egypt map (underlying map © Google)

Geography

Egypt is a land of duality and cycles, both in topography and culture. The geography is almost entirely rugged, barren desert, except for an explosion of green that straddles either side of the Nile as it flows the length of the country. The river emerges from far to the south, deep in Africa, and empties into the Mediterranean sea in the north after spreading from a single channel into a fan-shaped system, known as a delta, in its northernmost section. The river valley is flanked by imposing cliffs of limestone and sandstone, with deposits of other, harder stones like granite and granodiorite being found in the area of Aswan to the south.

One of the reasons for the overall stability of Egyptian culture was that it was largely isolated by virtue of its geography. With high cliffs and expansive deserts bordering the east and west, the sea at the north, and a series of huge rapids in the Nile to the south (known as cataracts), the stretch of the river valley that gave rise to dynastic Egypt was quite closed off from the outside. Egypt was undoubtedly the “gift of the Nile,” as the Greek historian Herodotus famously wrote. The influence of this river on Egyptian culture and development cannot be overstated without its presence, the civilization would have been entirely different. The Nile provided not only a constant source of life-giving water, but created the fertile lands that fed the growth of this unique (and uniquely resilient) culture.

View from the Nile River looking towards the Valley of Kings, showing the sharp delineation between the lush fertile land and the barren desert. (photo: Norman Walsh, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Each year, fed by melting snow in the far-off headlands deep in Africa, the Nile overflowed its banks in an annual flood that covered the ground with rich, black silt and produced incredibly fertile fields. The Egyptians referred to this area as Kemet, the “Black Lands,” and contrasted this dense, dark soil against the Deshret, the “Red Lands” of the sterile desert; the line between these zones was (and in most cases still is) a literal line. The visual effect is stark, appearing almost artificial in its precision.

Time—cyclical and linear

The annual inundation of the Nile was also a reliable and measurable cycle that helped form their concept of the passage of time. In fact, the calendar we use today in the west is derived from one developed by the ancient Egyptians. They divided the year into 3 seasons: akhet (“inundation”), peret (“growing/emergence”), and shemw (“harvest”); each season was divided into four 30-day months.

Although this annual cycle, paired with the daily solar cycle that is so evident in the desert, led to a powerful drive to see the universe in terms of cyclical time, this idea existed simultaneously with the reality of linear time. These two concepts—the cyclical and the linear—came to be associated with two of their primary deities: Osiris, the eternal lord of the dead, and Ra, the sun god who was reborn with each dawn.

The pharaoh—not just a king

Bronze figure of Isis nursing Horus, c. 4th century–3rd century B.C.E., bronze, 23.6 cm high, Egypt (British Museum)

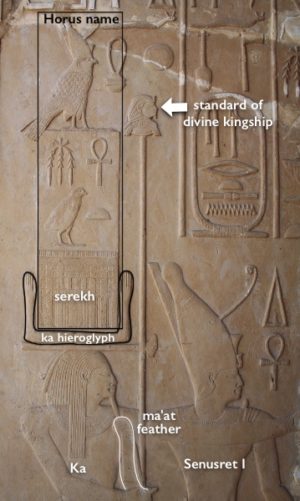

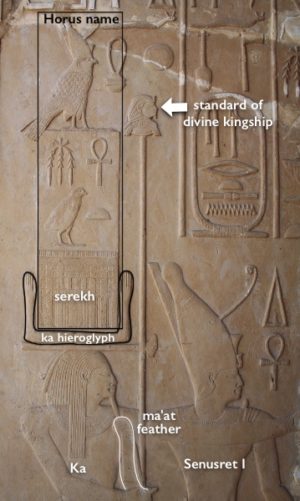

Rulers in Egypt were complex intermediaries that straddled the terrestrial and divine realms. They were, obviously, living humans, but upon accession to the throne, they also embodied the eternal office of kingship itself. The ka, or spirit, of kingship was often depicted as a separate entity standing behind the human ruler. This divine aspect of the office of kingship was what gave authority to the individual person who was the king. The living king was associated with the god Horus, the powerful, virile falcon-headed god who was believed to bestow the throne to the first human king.

Horus’s immensely important father, Osiris, was the lord of the underworld. One of the original divine rulers of Egypt, this deity embodied the promise of regeneration. Cruelly murdered by his brother Seth, the god of the chaotic desert, Osiris was revived through the potent magic of his wife Isis. Through her knowledge and skill, Osiris was able to sire the miraculous Horus, who avenged his father and threw his criminal uncle off the throne to take his rightful place.

Osiris became ruler of the realm of the dead, the eternal source of regeneration in the afterlife. Deceased kings were identified with this god, creating a cycle where the dead king fused with the divine ruler of the dead, and his successor “defeated” death to take his place on the throne as Horus.

The development of ancient Egypt

The civilization of Egypt obviously did not spring fully formed from the Nile mud; although the massive pyramids at Giza may appear to the uninitiated to have appeared out of nowhere, they were founded on thousands of years of cultural and technological development and experimentation.

Additional resources

More from Smarthistory on ancient Egypt’s early development and dynasties.

Read a Reframing Art History chapter on the world of ancient Egypt.

Read a Reframing Art History chapter about Ancient Egyptian religious life and afterlife.

Egyptian art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

Chronology of Ancient Egypt

Great Pyramids of Giza with modern Cairo in the foreground: Khufu (c. 2600–550 B.C.E.), Khafre (c. 2575–2525 B.C.E.) and Menkaure (c. 2525–2475 B.C.E.) (photo: Tim Kelley, CC BY-ND 2.0)

Beginnings

The civilization of ancient Egypt obviously did not spring fully formed from the Nile mud; although the massive pyramids at Giza may appear to the uninitiated to have appeared out of nowhere, they were founded on thousands of years of cultural and technological development and experimentation. “Dynastic” Egypt—sometimes referred to as “Pharaonic” (after “pharaoh”, the Greek title of the Egyptian kings derived from the Egyptian title per aA, “Great House,” which was used from the New Kingdom on)—which was the time when the country was largely unified under a single ruler, begins around 3000 B.C.E.

The depiction of King Den smiting an enemy stands near the beginning of a 3,000 year tradition. King Den’s sandal label, 1st dynasty. c.3000 BCE, ivory, found at Abydos, Upper Egypt, 4.5 x 5.3 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

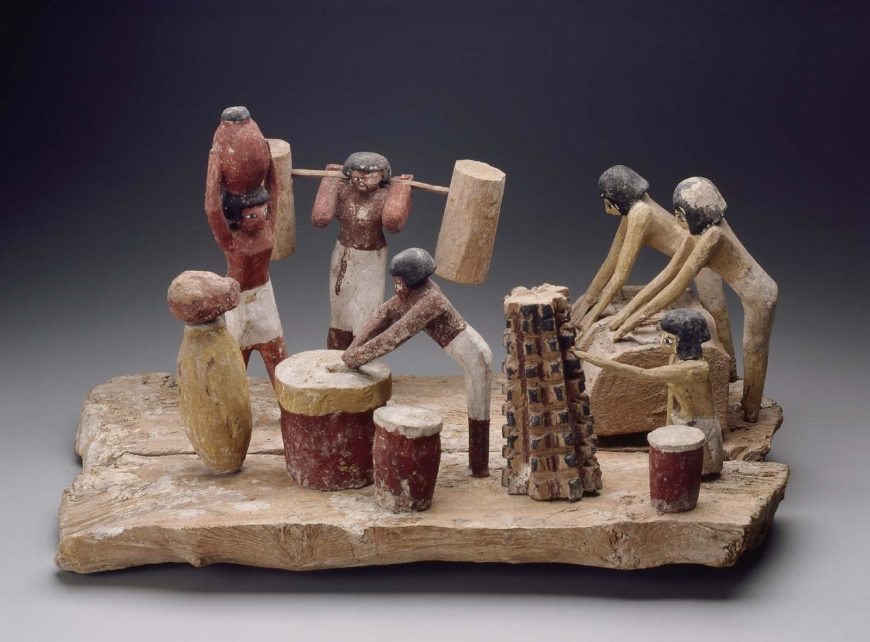

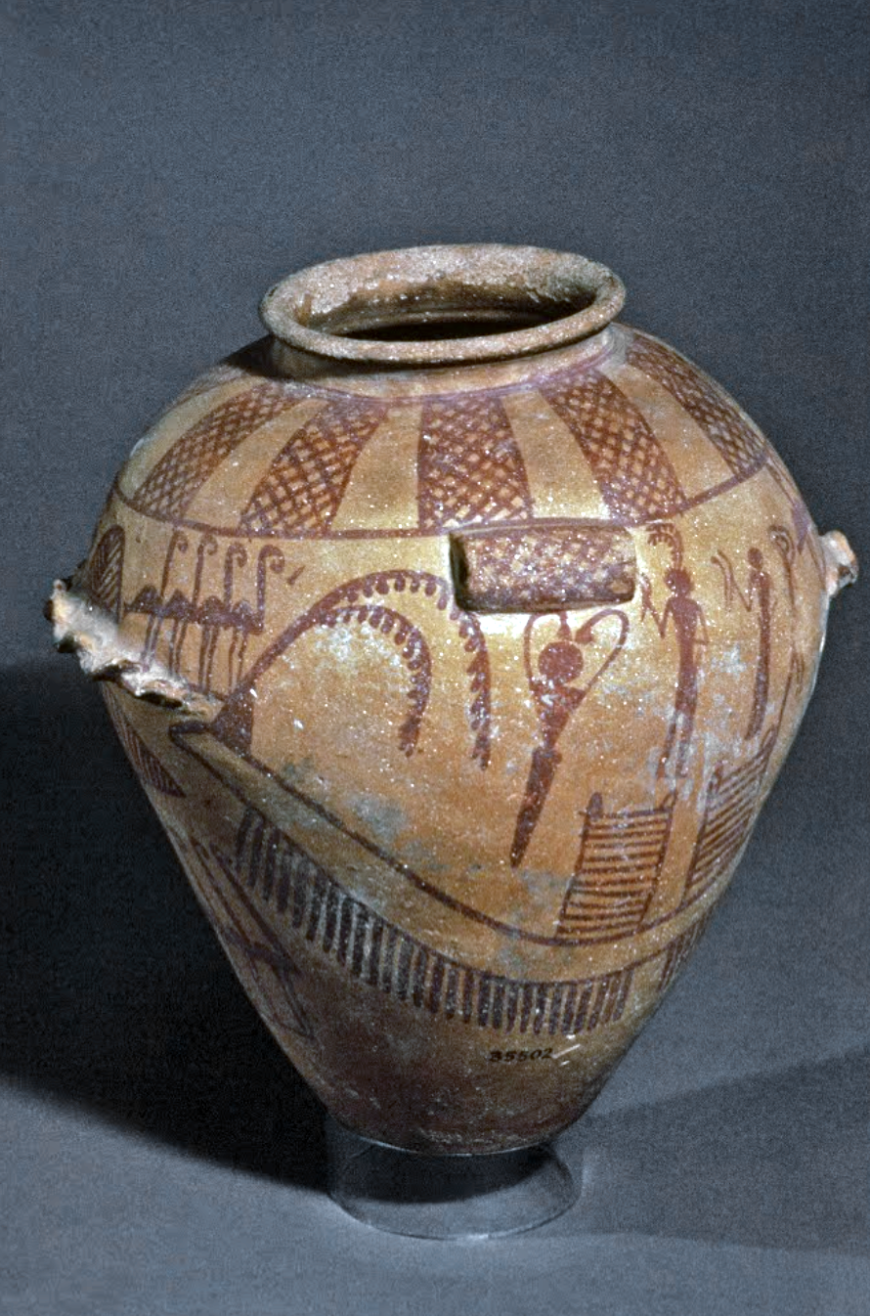

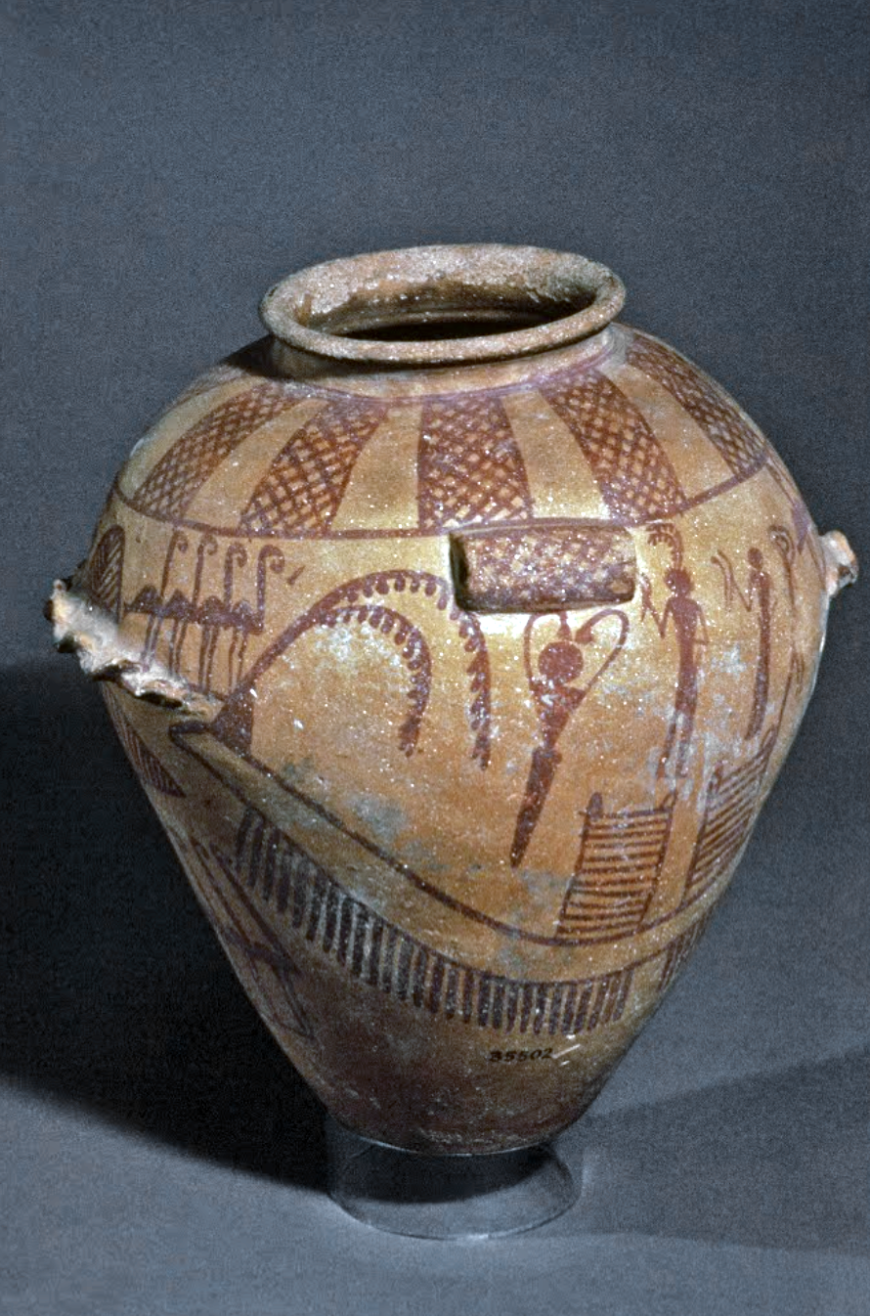

Decorated jar, c. 3500 B.C.E., predynastic period (Naqada II), pottery, found in a tomb in el-Amra, Egypt, 22.5 cm in diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

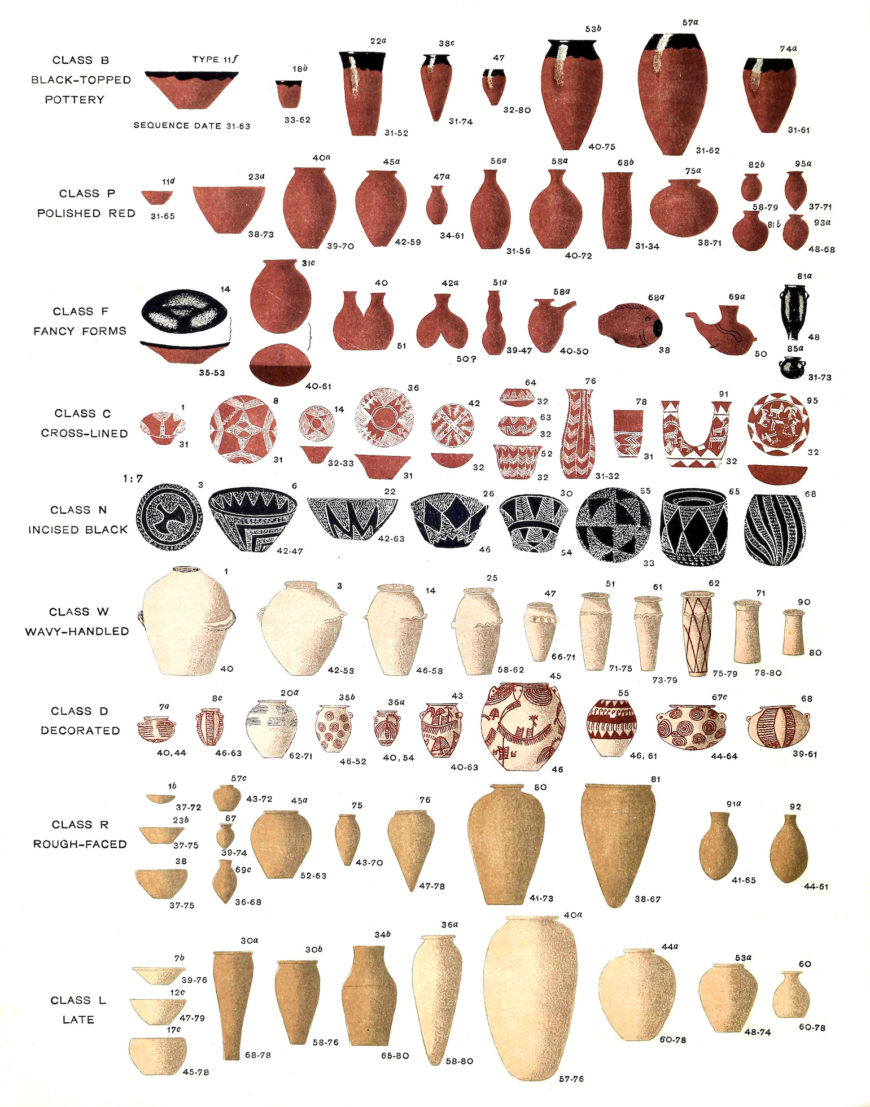

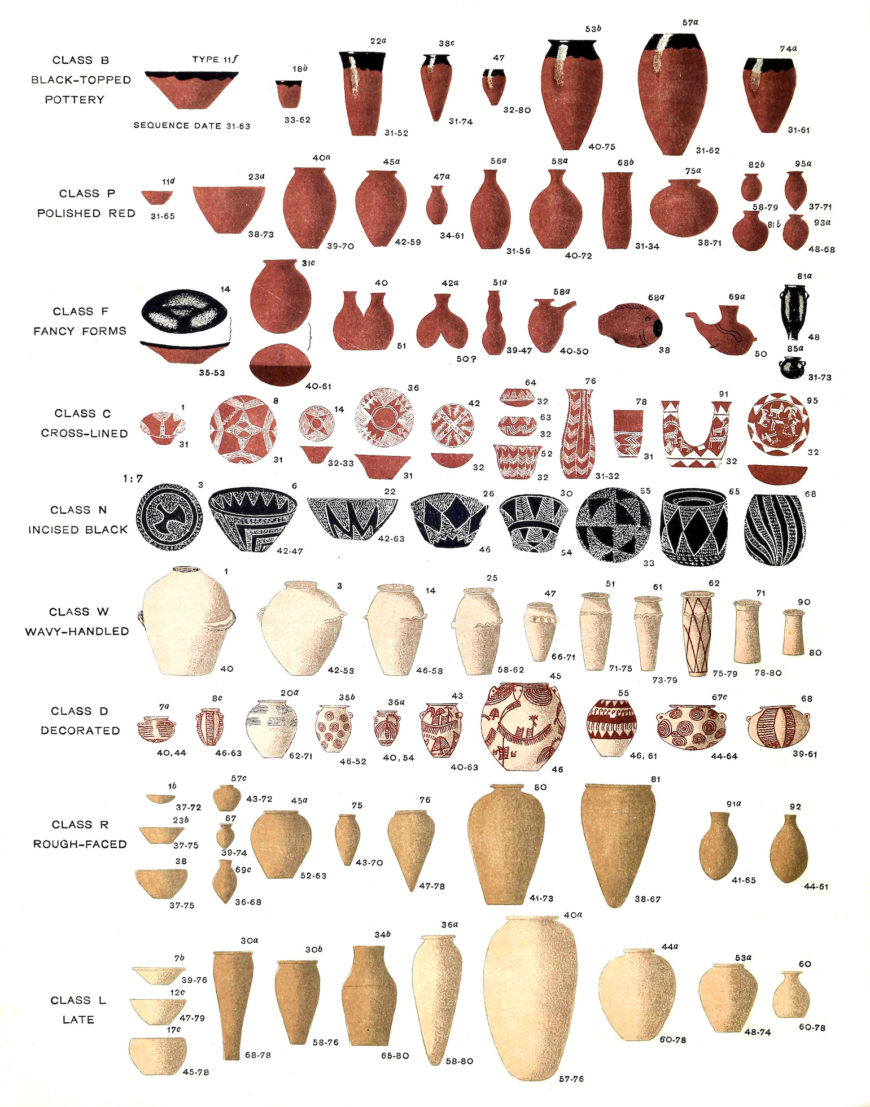

The period before this, lasting from about 5,000 B.C.E. until the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under one ruler, is referred to as Predynastic by modern scholars. Prior to this were thriving Paleolithic and Neolithic groups, stretching back hundreds of thousands of years, descended from northward migrating homo erectus who settled along the Nile Valley. During the Predynastic period, ceramics, figurines, mace heads, and other artifacts such as slate palettes used for grinding pigments, begin to appear, as does imagery that will become iconic during the Pharaonic era and we can see the first hints of what is to come.

Dynasties, periods, and reigns

It is important to recognize that the dynastic divisions modern scholars use were not used by the ancients themselves. These divisions were created in the first chronological history of Egypt, written by an Egyptian priest named Manetho in the 3rd century B.C.E. Each of the 30 dynasties included a series of rulers usually related by family connections or the location of their seat of power. Egyptian history is also divided into larger chunks, known as “kingdoms” and “periods,” to distinguish times of strength and unity (kingdoms) from those of change, foreign rule, or disunity (periods).

Like many other ancient cultures, the Egyptians themselves referred to their history in relation to the ruler of the time. Years were recorded as the regnal dates of the ruling king, so that with each new reign, the numbers began anew. The usual dating format included the day of the month and season, along with the regnal year of the king—for example, “day 4 of the second month of the season peret in the third year of Khafre.” This ancient practice creates challenges for modern historians, making it difficult to determine exact dating for many events and reigns; this is the reason that different resource books on ancient Egypt may provide slightly different dates for the same object. Generally, dates are provided here as “circa,” (c.) or approximate, for this reason.

Evolution of Egyptian prehistoric pottery styles, from Naqada I to Naqada II and Naqada III (Adapted from Diospolis Parva: the cemeteries of Abadiyeh and Hu, 1898–99)

Determining chronology

We do have some absolute dates based on recorded astronomical observations, such as the rising of the star Sirius, that have greatly aided the pursuit of a reliable chronology. However, these set points are few and far between. Much of the chronology modern scholars use is built around those anchored, calendrical and astronomical events. This is combined with relative dating methods based on the sequence of recognized changes in artifact characteristics over time (especially ceramics) and scientific dating methods, such as radiocarbon dating and thermoluminescence, that can be applied to organic materials but offer a date range, rather than a date.

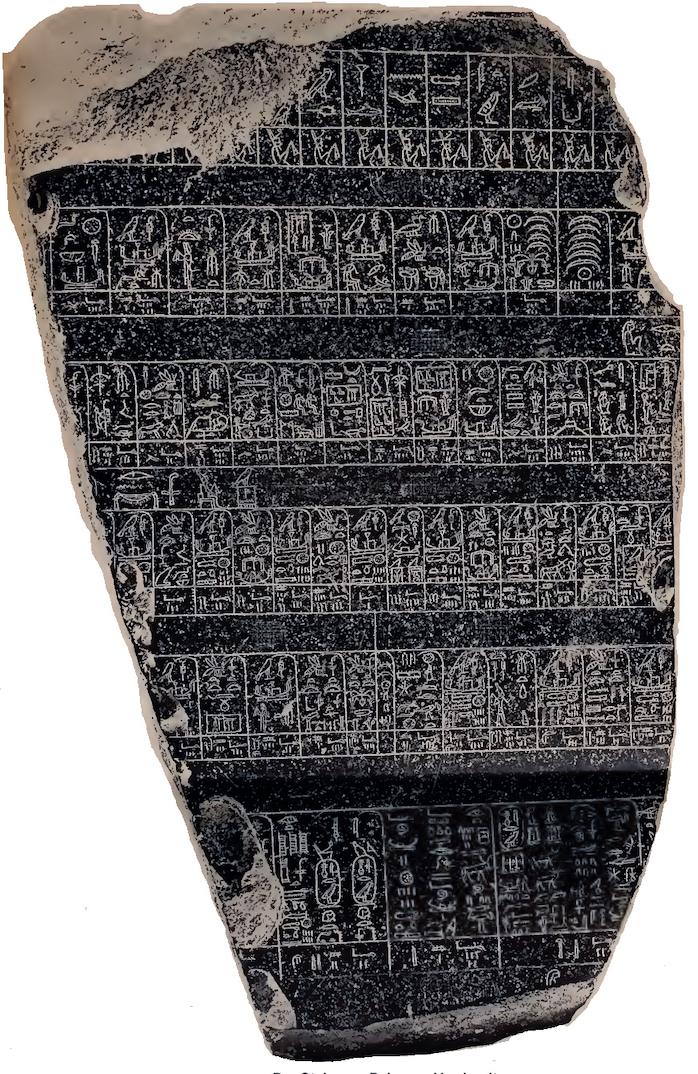

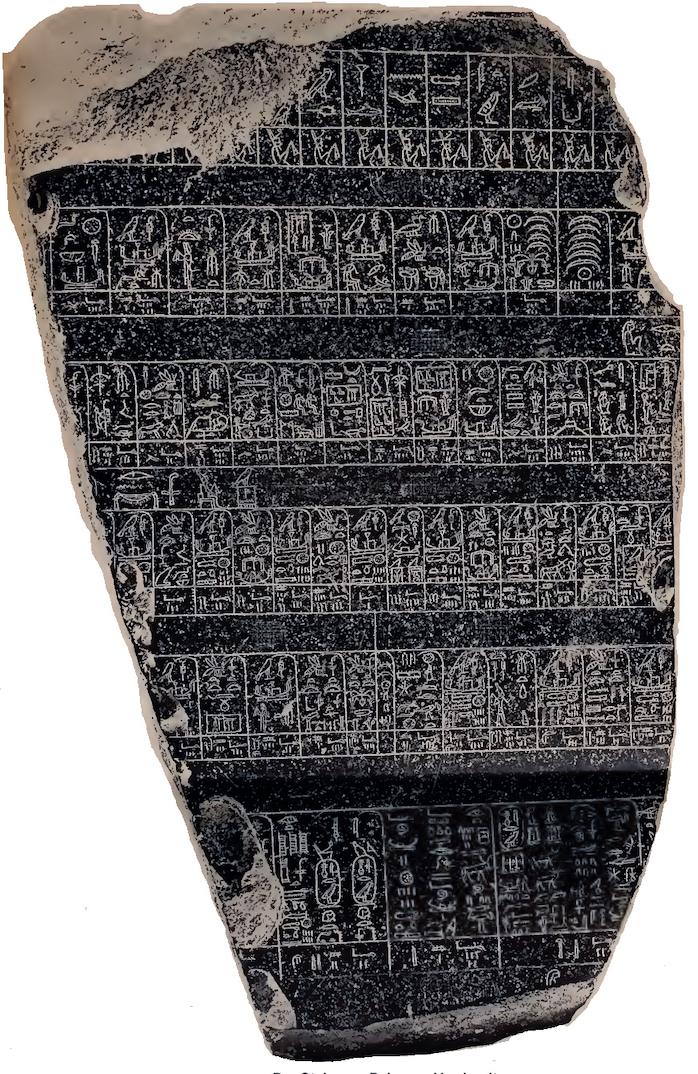

Palermo Stone, thought to have been created at the end of the 5th Dynasty (c. 2470 BCE) from p. 526 of Abhandlungen der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften aus dem Jahre… (Berlin: Verlag der Königlichen Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1901)

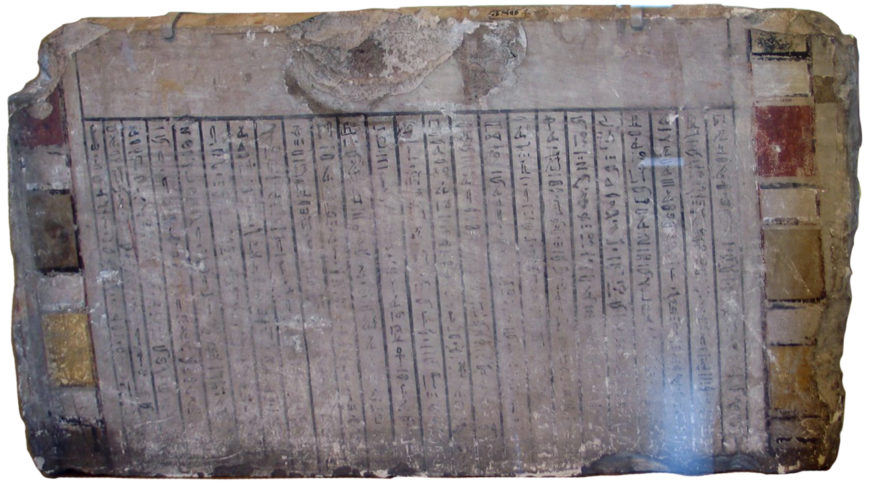

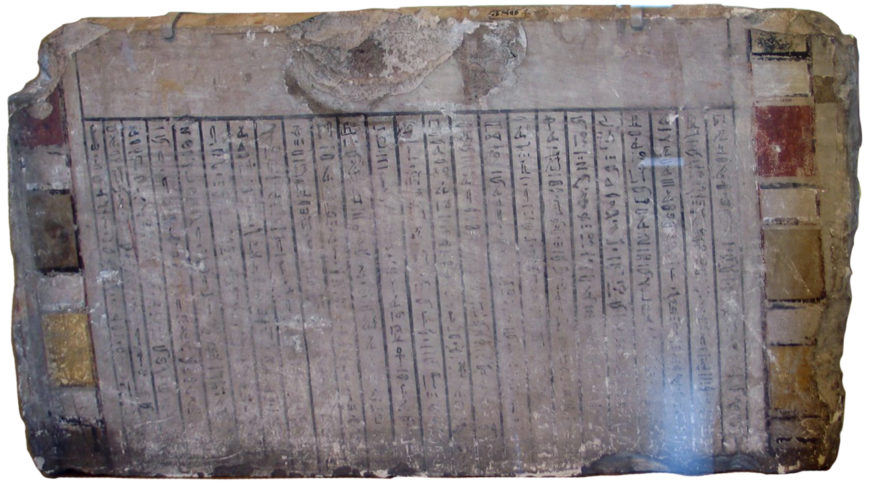

Manetho’s sources for his history are largely unknown. However, they would certainly have included annals, “day-books,” and ‘king-lists.’ These were records of the events that occurred during each king’s reign; unfortunately, few examples survive.

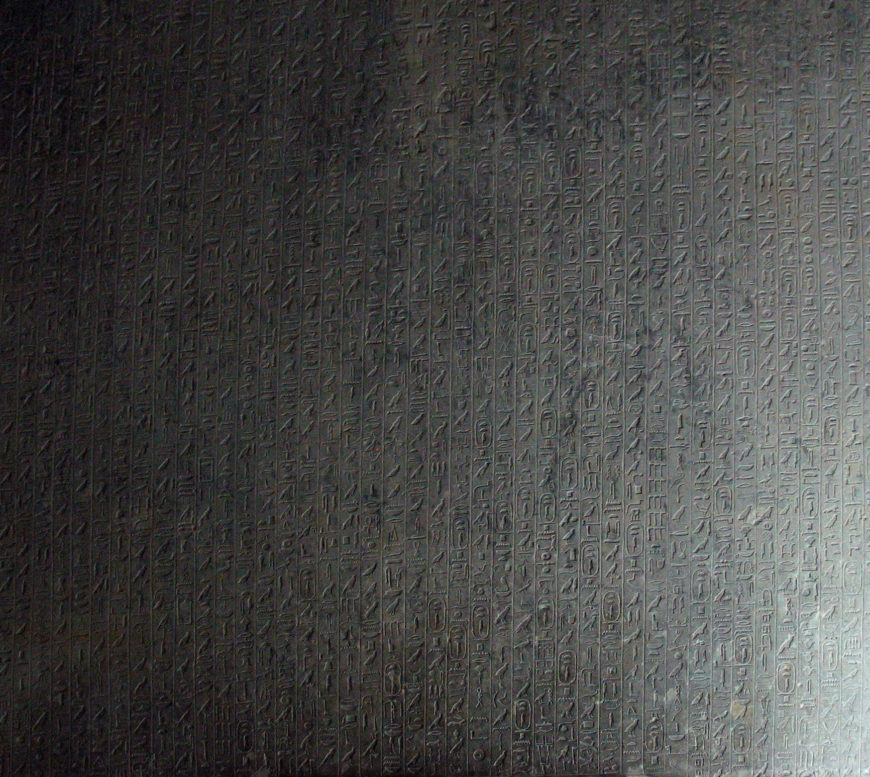

One of the most important surviving sources for the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom eras is a basalt stela fragment inscribed on both sides with royal annals stretching from the 5th Dynasty back to the mythical rulers of the Predynastic period. Known as the Palermo Stone, this slab was discovered in 1866 and records major cult ceremonies, building projects, details of Nile inundations, taxation reports, and warfare events.

A King List with the names of 76 rulers from ancient Egypt. Detail of the King List, 19th Dynasty c. 1279 B.C.E., from the Temple of Seti I, Abydos, Egypt (photo: Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0)

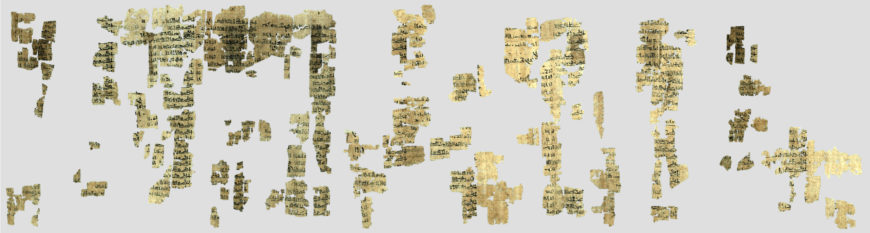

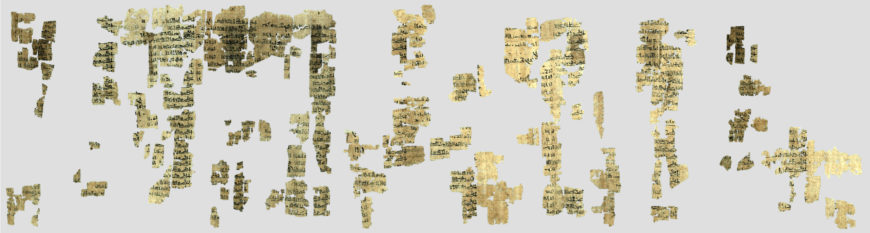

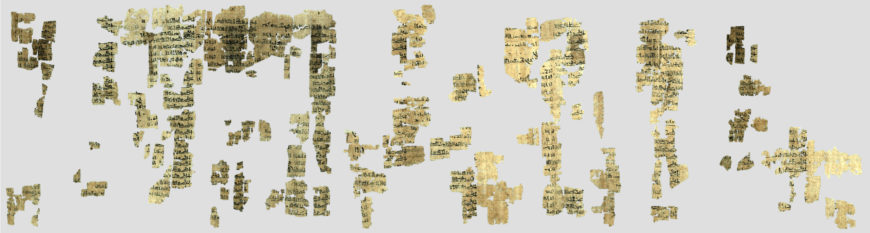

King-lists were also inscribed on the walls of some temples—one of the best-known being from the temple of Seti I at Abydos—and were written on papyri, although only one such example survives (the so-called Turin Canon from the thirteenth century B.C.E.).

The Turin king list, or the Royal Canon of Turin, 1275–1200 B.C.E., papyrus (Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy ; photo: Pharoah.se, CC BY)

This valuable, but fragmentary, document records the list of kings and the length of their reigns stretching from the Second Intermediate Period back to the earliest kings from the 1st Dynasty. These lists were not necessarily focused on recording “history.” Instead, they were a form of ancestor worship, where the current ruler celebrated the consistency of kingship and presented their predecessors as a combination of the general, eternal concept of divine kingship and the individual, human ruler who held power at that specific moment.

| Period |

Dates |

| Predynastic |

c. 5000–3000 B.C.E. |

| Early Dynastic |

c. 3000–2686 B.C.E. |

| Old Kingdom (the ‘pyramid age’) |

c. 2686–2150 B.C.E. |

| First Intermediate Period |

c. 2150–2030 B.C.E. |

| Middle Kingdom |

c. 2030–1640 B.C.E. |

| Second Intermediate Period

(Northern Delta region ruled by Asiatics) |

c. 1640–1540 B.C.E. |

| New Kingdom |

c. 1550–1070 B.C.E. |

| Third Intermediate Period |

c. 1070–713 B.C.E. |

| Late Period

(a series of rulers from foreign dynasties, including Nubian, Libyan, and Persian rulers) |

c. 713–332 B.C.E. |

| Ptolemaic Period

(ruled by Greco-Romans) |

c. 332–30 B.C.E. |

| Roman Period |

c. 30 B.C.E.–395 C.E. |

Periods and main characteristics

Egypt went through many waves of cultural development. Although its early development of beliefs, social structures, and imagery remained stable and iconic for millennia to come, later periods introduced new ideas that required adjustment. The Egyptians were extremely flexible because of their core stability, based on central beliefs that were set very early in their history. The following time periods, with their major events and unique characteristics, are the chapters in a story that stretches back to 5000 B.C.E.

Predynastic and Early Dynastic

Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period

Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period

New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period

Late Period and Ptolemaic and Roman Periods

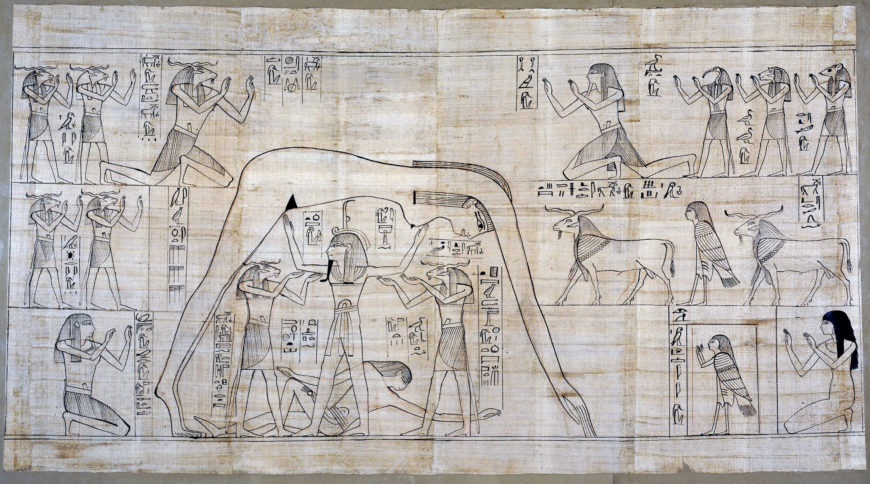

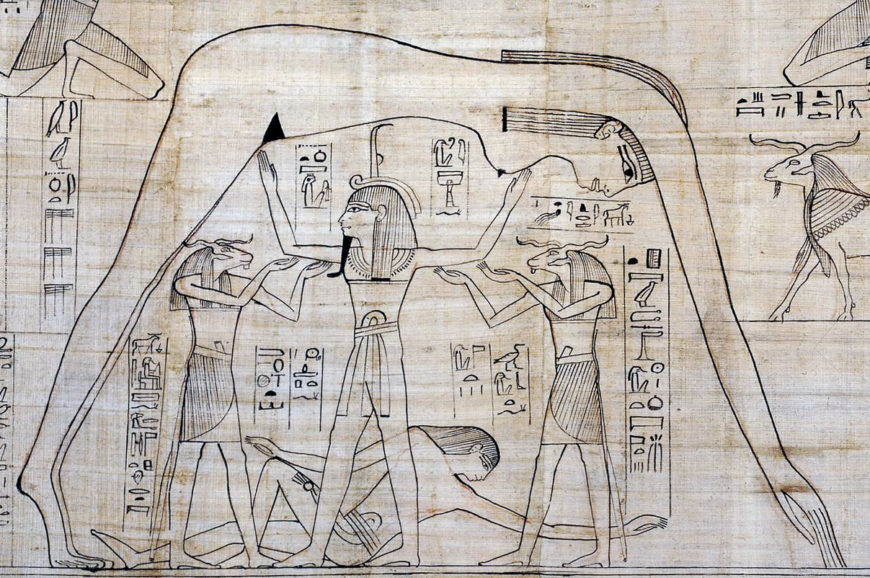

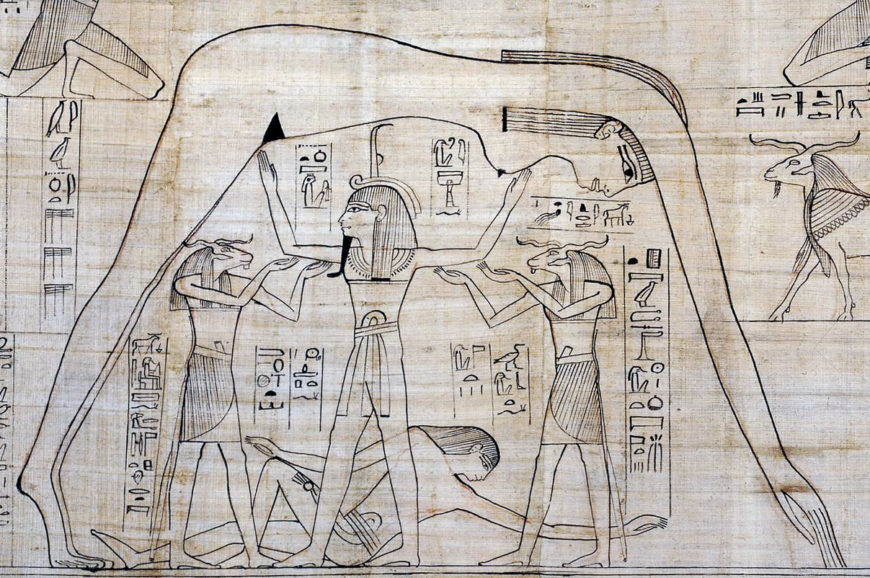

Creation Myths

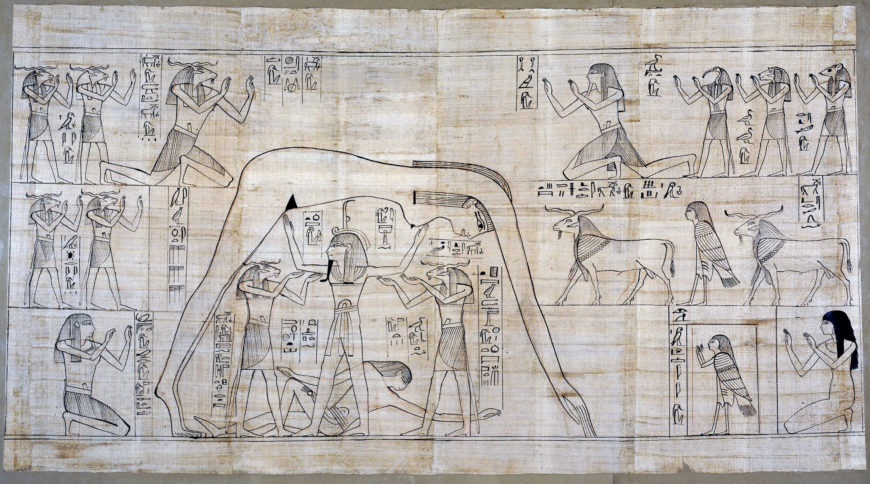

Full page black line vignette of the deities Geb, Nut, and Shu. Geb, god of the earth, stretches out below the sky-goddess Nut, who arches overhead. They are separated by the god of air, Shu, who is supported in this task. The deceased kneels to the lower right, accompanied by her ba-spirit and surrounded by groups of gods. The Greenfield Papyrus, c. 950–930 B.C.E., 21st–22nd dynasty, papyrus, excavated at First Cache, Upper Egypt, Deir el-Bahri (the Book of the Dead of Nesitanebtashru) (© Trustees of the British Museum)

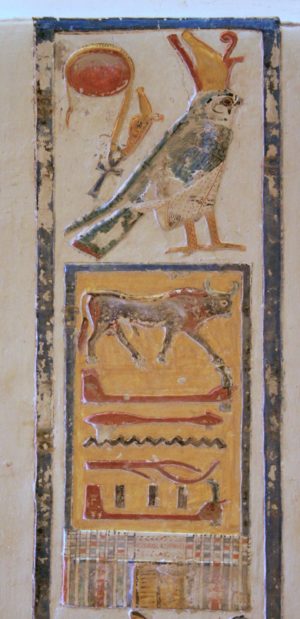

Lord of Chaos, the god Seth was associated with a distinctive and unidentified animal with squared-off ears and an elongated, down-curved snout, Karnak, Egypt (Open Air Museum, Karnak; photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

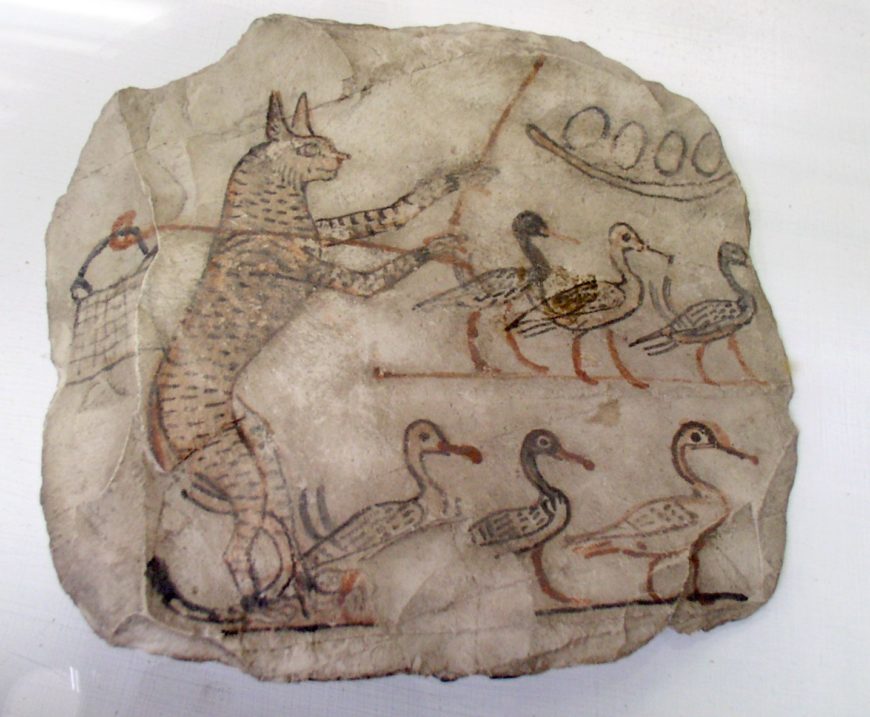

Egypt’s mythic world, rich with creative imagery, was deeply informed by the natural world that surrounded them. The divine landscape and the stories about the beings that inhabited it continued to evolve through Egyptian history. Over time, these myths wove an elaborate tapestry of meaning and significance, often presenting layered, seemingly contradictory viewpoints that existed simultaneously without apparent conflict.

Ourobos (detail), a shrine from the tomb of Tutankhamun, 18th dynasty, New Kingdom of Egypt (Egyptian Museum, Cairo; photo: Djehouty, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Similarly, the concept of time in ancient Egypt was rather fluid; it was believed to move at different rates for certain beings and regions of the cosmos and was viewed as simultaneously linear and cyclical. Obviously, individual Egyptians experienced linear time—living their lives from birth to death—but they were also intimate with cyclical time, as evidenced in nature by the solar cycles, annual floods, and repeating astronomical patterns. They believed that an ongoing cycle of decay, death, and rebirth was what provided for the eternal consistency of the stable universe and allowed it to flourish. Fittingly, the ouroboros—the image of a snake eating its own tail and potent symbol of regeneration—originated in Egypt.

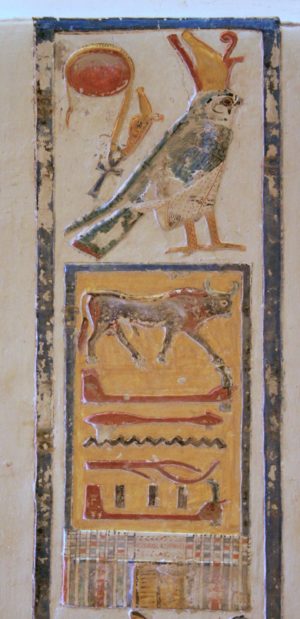

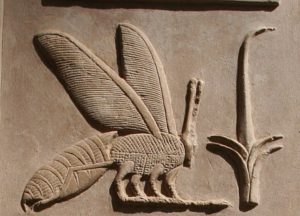

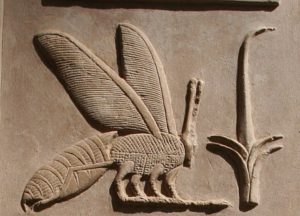

The prehistoric peoples of the Nile region, like many other early populations, revered powers of the natural world, both animate and inanimate. While some deities, like the sun god Ra, were linked with inanimate natural phenomena, most of the first clear examples of divinities were connected to animals. Falcon gods and cattle goddesses were among the earliest and may well have developed in the context of Neolithic cattle herding.

The enigmatic scenes on this monumental macehead have been much debated. They could represent the king’s heb-sed festival, divine rituals, or a royal wedding, among other possibilities. In this view, there are divine standards being carried in the top register, while the lower register shows cattle, goats, and a kneeling human with numbers under them indicating how many were captured or being presented. Narmer Macehead, Early Dynastic Period, c. 31st century B.C.E., found in Hierakonopolis (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

Already in the Early Dynastic period (c. 3100–2686 B.C.E.), there is significant evidence for the existence of many deities that were represented in human, animal, or hybrid forms (usually with human bodies and animal heads). Cult objects (statues of gods) in their local shrines shown being revered by the king were depicted on objects found in royal tombs of this period and may record actual visits by the ruler to different parts of the country to engage with those deities. The dedication of such cult images and participation in their rituals by the king was one of the most essential royal duties. Around 3000 B.C.E. when Egypt was unified under a single ruler, these disparate local deities appear to have been organized into a pantheon with relationships created between them, and these connections may have sparked various mythic stories.

The Turin king list, or the Royal Canon of Turin, papyrus

There are great challenges in the study of Egyptian mythology, not the least of which are the large gaps in our knowledge due to the whims of preservation. Our most cohesive records are texts from the later periods, which often record detailed stories that present seemingly contradictory accounts. For example, there were diverse and complementary creation myths and cosmogonies (stories about the origins of the universe) that overlap to present different aspects of their understanding of how the world and the gods came into being. In the view of the ancient Egyptians, there were seven stages to the mythical timeline of the world:

- the chaos that existed pre-creation,

- the emergence of the creator deity,

- the creation (by various means) of the world and the differentiation of beings,

- the reign of the sun god,

- direct rule by other deities,

- rule by human kings, and

- a return to the chaos of the primeval waters.

At different times and in various locations, a variety of deities were identified with the creator god who emerged from the primordial waters to initiate and differentiate the cosmos. These included Ra, Atum, Khnum, Ptah, Hathor, and Isis. These myriad versions of the process of creation were connected to and promoted by cult centers, that emphasized the role of their patron deity in the process.

The three major variations of the Egyptian creation story are commonly referred to today by the cult locations where these variations were most heavily promoted: Hermopolis (Khemnu), Heliopolis (Iunu), and Memphis (Ineb-hedj).

While they differ in the details and focus on the primacy of their own local deities, all these creation systems are also quite similar in their approach, where a chaotic, amorphous watery mass of potentiality was brought under control through the establishment of ma’at and given form through the will of a creator. Many variations on these themes appeared that fit into the basic frameworks—the emerging sun god was sometimes visualized as a falcon, a scarab beetle, or a child (among other manifestations)—but all materialized from a mound and/or primeval waters. An understanding of these overlapping creation myths, and a recognition of the fact that they existed simultaneously with no apparent conflict, hints at the complexity of the mythological world of ancient Egypt.

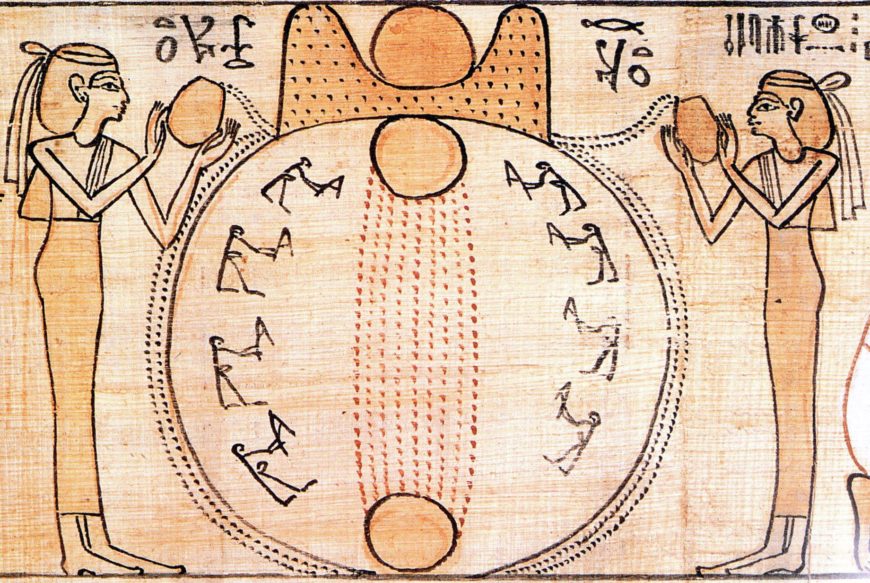

Creation Myths

Hermopolis—cult center of the Eight

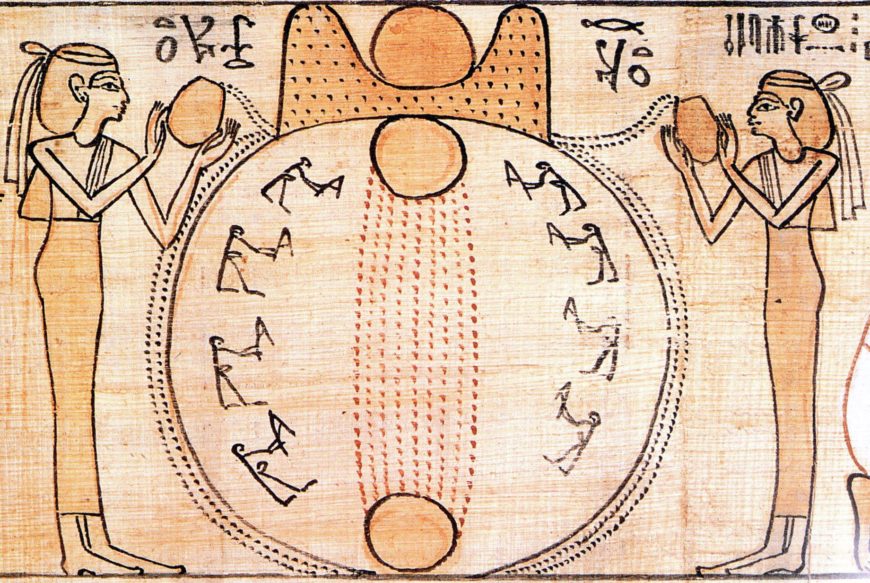

The sun rises from the mound of creation at the beginning of time. The central circle represents the mound, and the three orange circles are the sun in different stages of its rising. At the top is the “horizon” hieroglyph with the sun appearing atop it. At either side are the goddesses of the north and south, pouring out the waters that surround the mound. The eight stick figures are the gods of the Ogdoad, hoeing the soil. “The Creation of the World,” detail in the Book of the Dead of Khensumose, c. 1075–945 B.C.E., Twenty-first Dynasty (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

The Hermopolitan view (centered in Hermopolis) presented a vision of creation as a mound of earth that emerged from the primordial waters of chaos. A lotus blossom grew from this mound, opened, and revealed the newborn sun god, which brought light to the cosmos and initiated creation. Within the primeval waters were believed to be four pairs of male and female deities, known as the Ogdoad (“group of eight”) who represented elements of the pre-creation cosmos. Often represented with the heads of frogs and snakes, these chthonic beings as being associated with the primeval flood. Until the first light appeared, these beings were viewed as inert, containing the potential of creation but only “activated” when the young sun emerged from the lotus. The names of these deities, who were considered the “mothers” and “fathers” of the sun god, were masculine and feminine versions of the elements: Water (Nun & Nunet), Infinity (Heh & Hauhet), Darkness (Kek & Kauket), and Hiddenness (Amun & Amaunet).

Heliopolis —cult center of Atum

Detail of the air god Shu, assisted by other gods, holds up Nut, the sky, as Geb, the earth, lies beneath. From The Greenfield Papyrus, c. 950–930 B.C.E., 21st–22nd dynasty, papyrus, excavated at First Cache, Upper Egypt, Deir el-Bahri (the Book of the Dead of Nesitanebtashru) (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The sun god plays a primary role in the Heliopolitan creation theology. In this system, creation was enacted by a group of deities referred to as the Great Ennead. This “group of nine” consisted of the sun god, in his form as Atum, and a series of eight descendents. In this story, Atum already existed in the primordial waters (sometimes said to have been “in his egg”) and emerged alone to initiate creation. Atum was said to be “he who came into being by himself”and he then created his first two descendants, Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture) from his bodily fluids. Shu and Tefnut then created the next pair of gods, Geb (earth) and Nut (sky), providing the physical framework for the world. Geb and Nut then produced the gods Osiris and Isis, and Seth and Nephthys. These pairs, in one sense, represented the fertile Nile valley (Osiris & Isis) and the desert that surrounded it (Seth & Nephthys), completing the primary elements of the Egyptian cosmos. As all these deities were viewed as being extensions of and proceeding from the sun god, he was generally portrayed as the ruler of the gods.

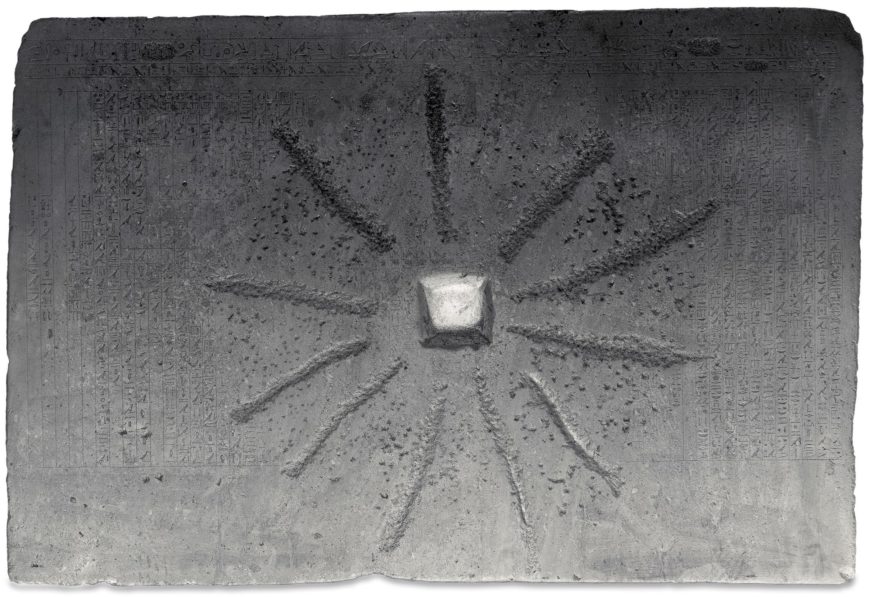

Memphis—cult center of the great craftsman Ptah

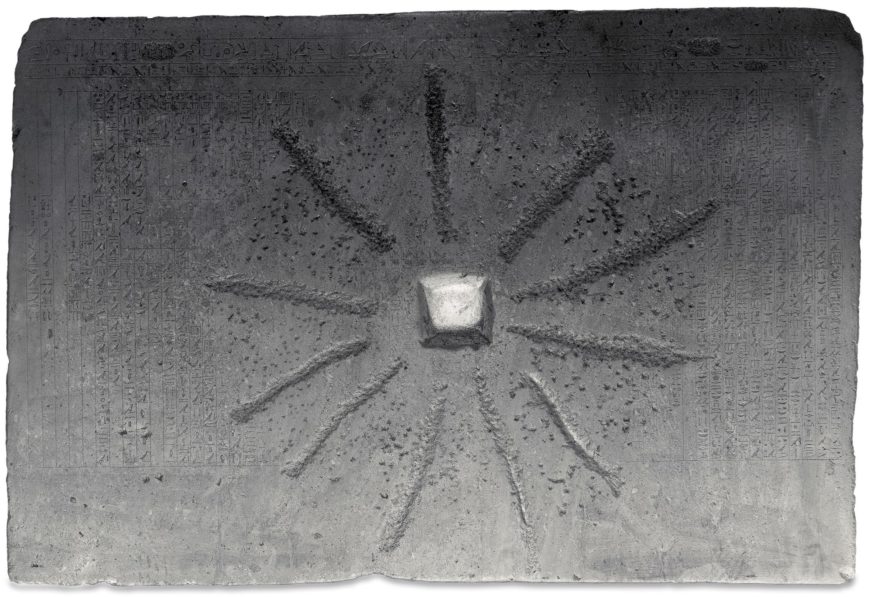

This slab was reused as a millstone, which is why it is horribly worn in that spoke pattern. If you zoom in on the image you have, you will see the vertical lines of text. The Shabako Stone, 710 B.C.E., 25th dynasty, found in Memphis, Egypt, 95 x 137 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The Memphite Theology is recorded on an important artifact now known as the Shabaka Stone. This black basalt stelae was originally set up in the ancient temple of Ptah at Memphis and preserves the only surviving copy of this religious text. According to the inscription, which is heavily damaged, the text of the stelae was copied from an ancient worm-eaten papyrus that the pharaoh Shabaka ordered to be transcribed in order to preserve it (this story, however, is debatable). The text contains references to the Heliopolitan account but then claims that the Memphite god, the chthonic Ptah, preceded the sun god and created Atum. Ptah was viewed as the “great craftsman” and the text alludes to creation being enacted through his conscious will and rational thought—the form of the earth was described as being brought about via his creative speech.

These variations on core mythic elements may have resulted from attempts to incorporate deities that emerged at various times and locations into an existing framework of creation stories.

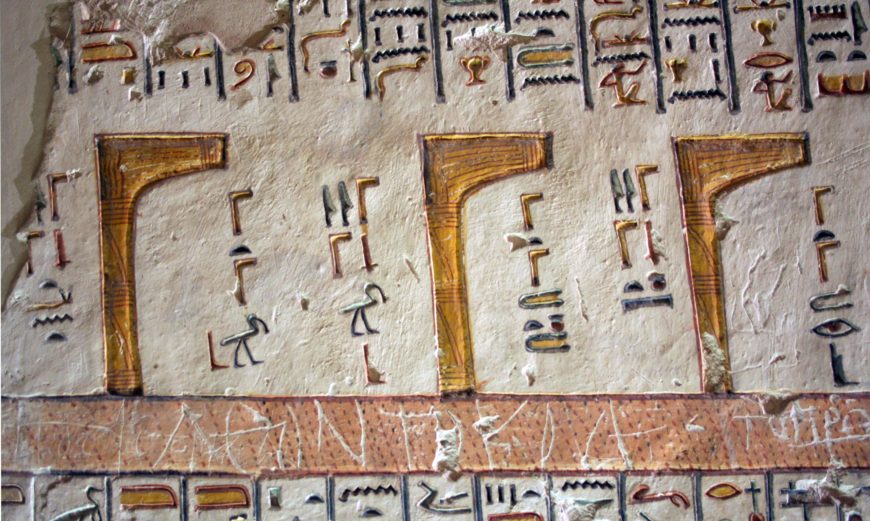

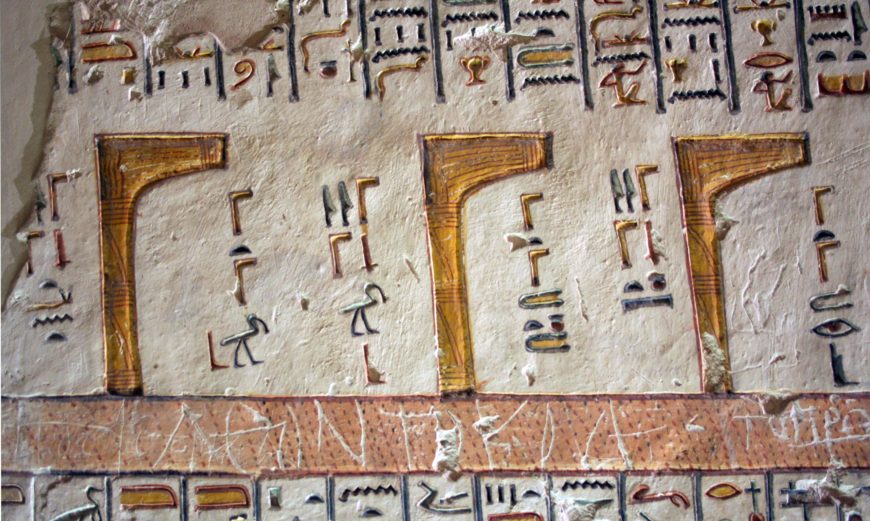

Netjer hieroglyph written as a wrapped pole with a flag on top. A row of netjer signs from the tomb of Ramses VI (KV9). Painted details show the pattern of the wrapping used on these divine symbols (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

The form(s) of the gods

The Egyptian word that modern scholars translate as “god” is netjer, which is written in hieroglyphs as a wrapped pole with a flag on top—a symbol of divine presence that dates back to Predynastic times. However, it is clear that this term encompassed not only what we would consider gods, but also deified humans, other types of supernatural beings, and even chaotic monsters (like the great serpent Apophis who was the chief foe of the sun god Ra). Spirits of the deceased (akhu), demon-like dwellers of the underworld, and beings called bau, which were manifestations of the gods that served as their messengers, were also feared and revered.

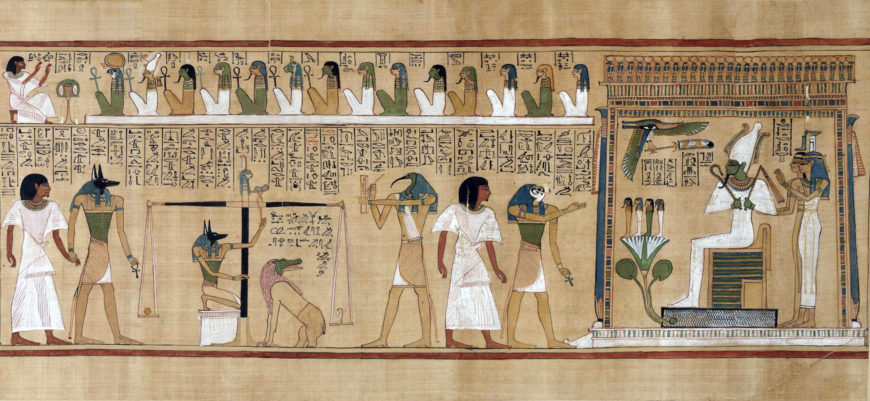

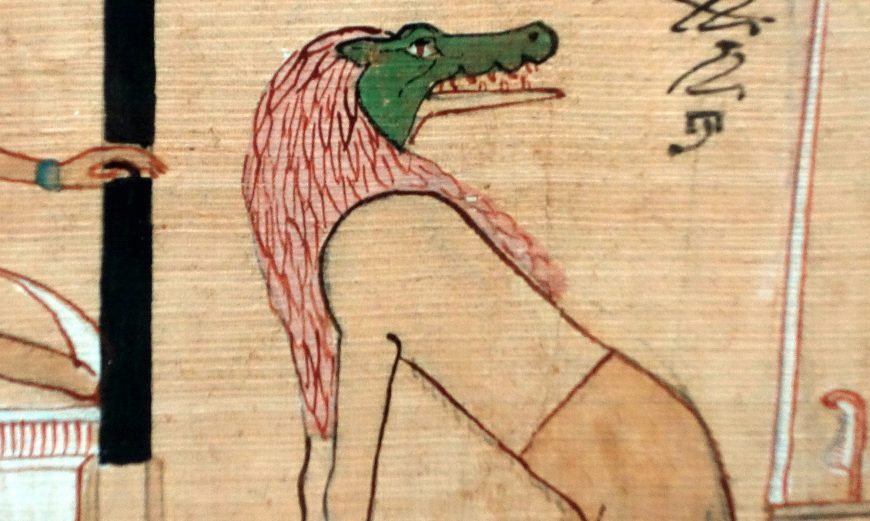

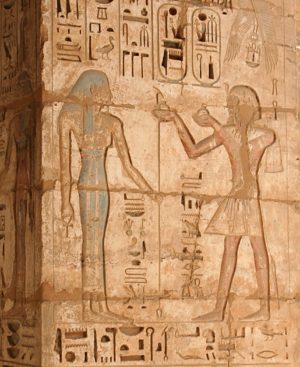

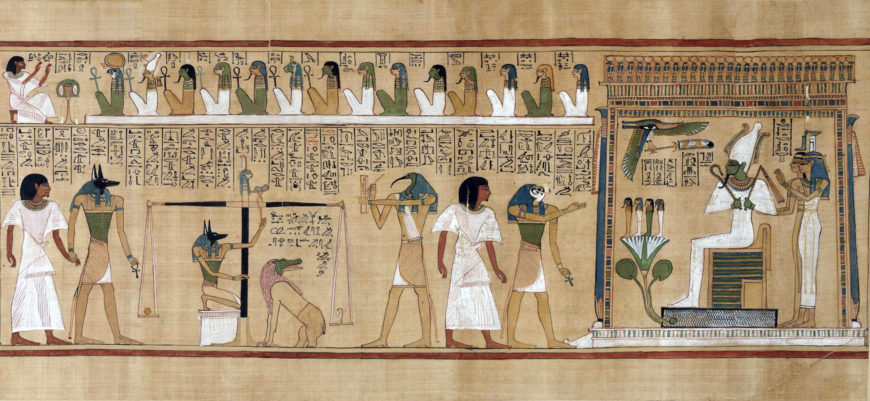

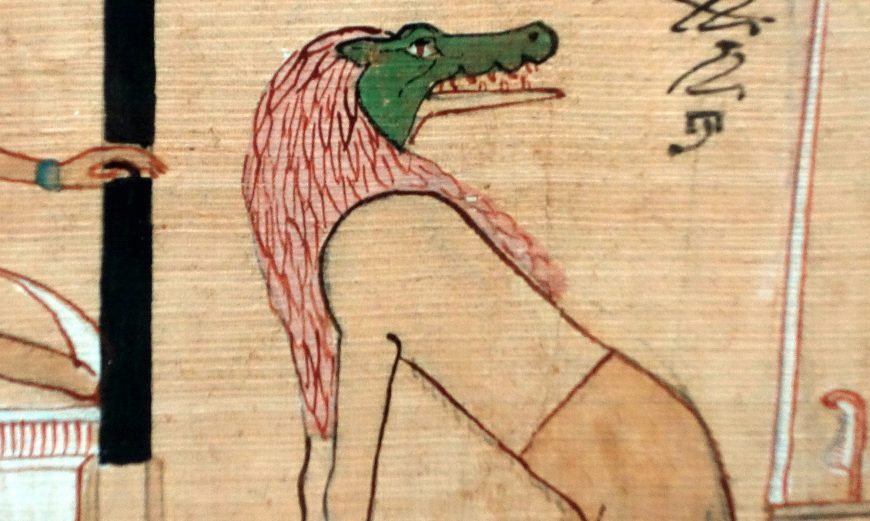

The human Hunefer being led by Horus (falcon-headed) to stand before Osiris (seated), with Isis and Nephthys behind him. Judgement in the presence of Osiris, Book of the Dead, 19th Dynasty, New Kingdom, c. 1275 B.C.E., papyrus, Thebes, Egypt (British Museum)

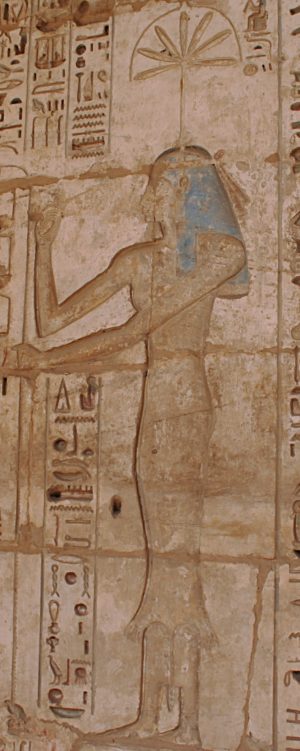

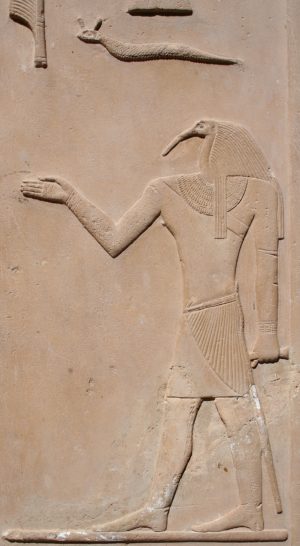

The gods took various physical forms: anthropomorphic (human), zoomorphic (animal), hybrid (with the head of either a human or animal and the body of the opposite type), and composite (where characteristics of different deities were merged into one form). Many deities were fluid in the way they were represented and a truly fixed form for any deity was quite uncommon—sometimes, only the name clearly specifies which deity is being represented. The god Thoth, for example, was often depicted with a human body and the head of an ibis but could also be represented in fully-animal form as an ibis or as a baboon.

Capital of Hathor with a human head and bovine ears (left) and Hathor in Bovine form (right), both from the Temple of Queen Hatshepsut, Dayr al-Baḥrī, Egypt, c. 1470 B.C.E. (photos: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Few deities were shown in all three main representational modes, but there were exceptions, such as the goddess Hathor, who could be portrayed fully human, fully bovine, or as a woman with a cow head. Keep in mind that these representations were not what the gods actually looked like in the Egyptian conception. Instead, they were visualizations of the deities’ characteristics, providing physical forms that allowed for interaction with the gods.

Wall relief of The Theban Triad, Amun, Mut, and Khonsu (left to right), mortuary temple of Ramses III, Medinet Habu, Theban Necropolis, Egypt (photo: Rémih, CC BY-SA 3.0)

There were also many other types of groupings of deities, especially triads. These father-mother-child groupings, like the Theban Triad of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu, were viewed collectively in certain contexts but each still maintained their individuality. Rather different was a practice known as syncretism where different deities were merged into one body. This appears to have been an effort to acknowledge when a deity was dwelling “within” another deity when performing roles that were primarily functions of the other. Often these were combinations of similar deities or different aspects of the same god, such as Atum-Khepri, which combined the dusk and dawn manifestations of the sun god. Other examples merged deities of very different nature, such as Amun-Ra, where the “hidden one” (mentioned above) was combined with the visible power of the sun to create the “King of the Gods.”

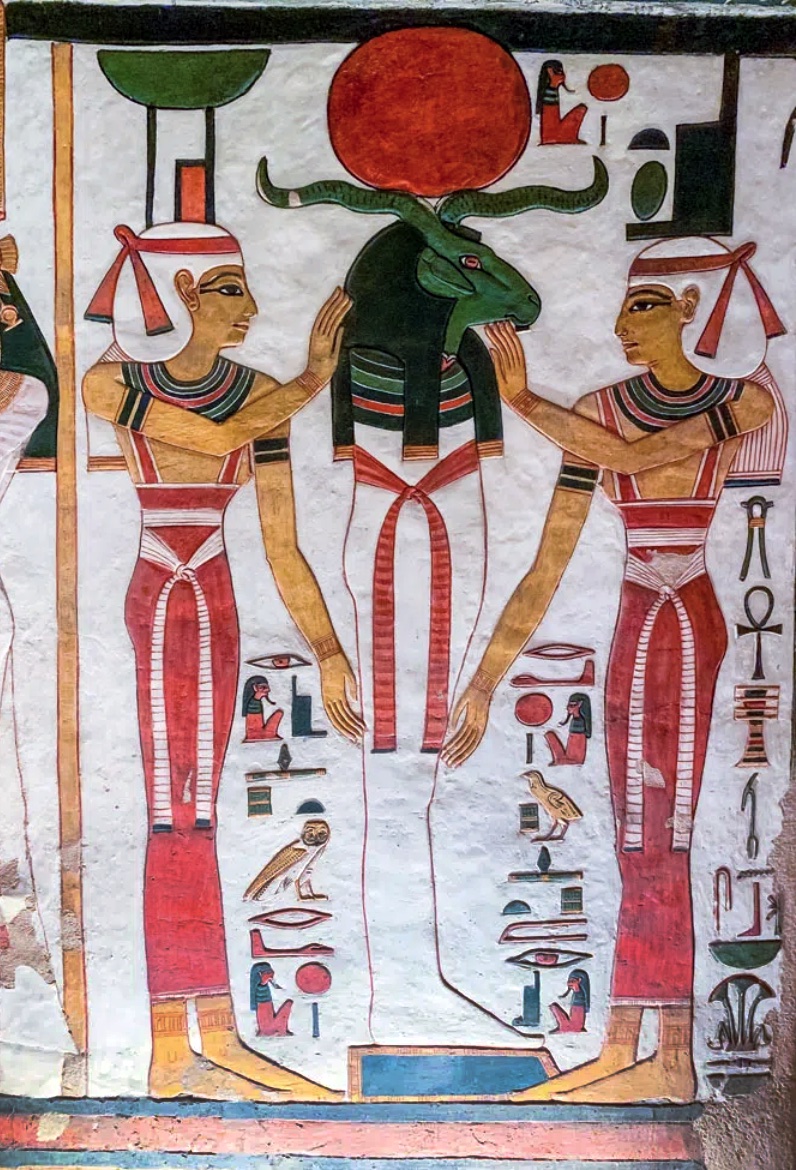

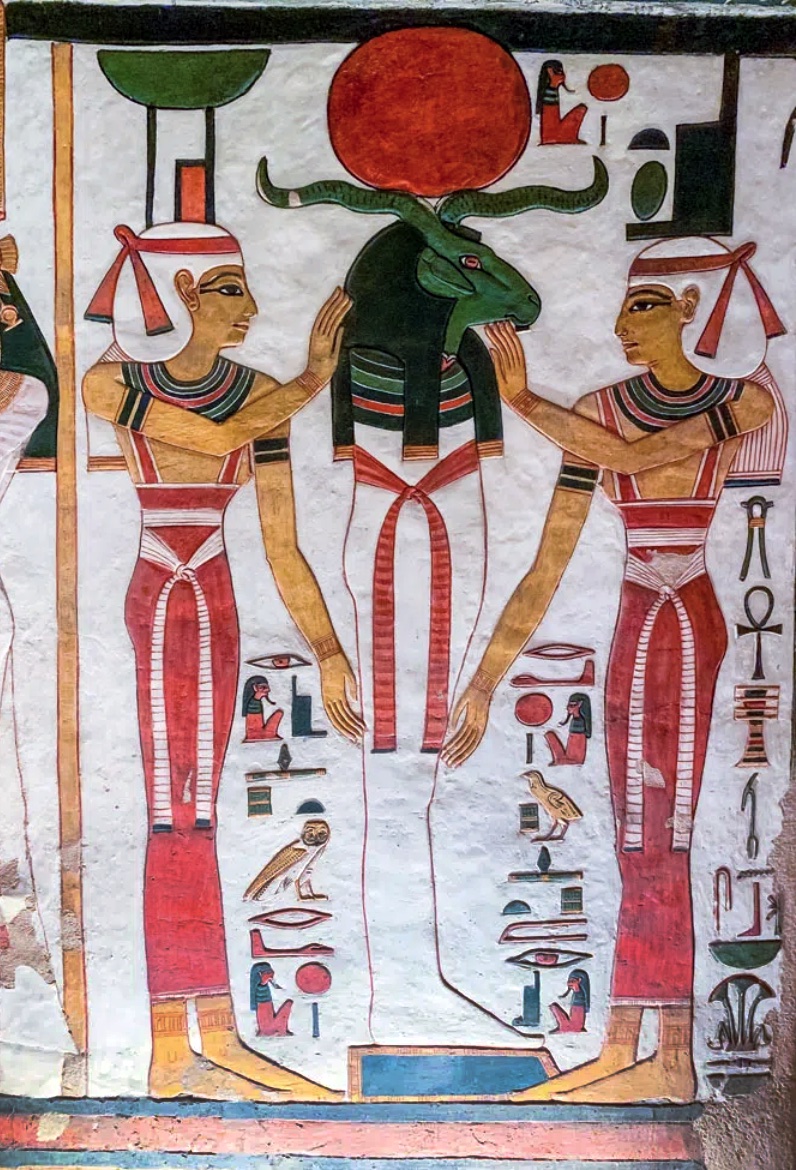

Ra and Osiris merged into one (center figure), tomb of Nefertari, 19th dynasty c 1290 1220 BCE, Middle Kingdom, West Thebes Egypt

Death, cycles, and the end of time

Egyptian deities were not static beings. Osiris, one of their most important gods, actually died (although the texts never directly say this, they do refer to him being dismembered, mummified, and buried) and then was transformed into the Lord of the Underworld. Others, like the sun god Ra, had cycles—Ra was believed to reach his zenith at midday (as Harakhti), grow old at the end of the day (as Atum), “die” at night, merging with Osiris in the depths of the netherworld to enact regeneration, and then was resurrected again with the dawn (as Khepri). In the Egyptian view, life led to death and then death re-emerged as new life; this cycle applied to humans and the gods alike, enabling them to become young again with eternal sameness.

At the end of time, the Egyptians believed that all the variety of the cosmos, including the gods, would revert to the undifferentiated condition of time before creation, with everything merging back into the primeval waters of potentiality.

Egyptian Deities

Egyptian mythology and religious beliefs evolved and morphed over time. There was no official “holy book,” nor was there an “authorized version” of the stories gathered together into a single text. Instead, the study of Egyptian religious beliefs requires piecing together visual and written sources into a lived experience. This evidence is also surprisingly fragmentary. For instance, for many periods and regions we lack surviving temples (chief sources for ritual representations and texts) and domestic settings (rich sources of shrines and evidence of day-to-day religious practices).

One of the earliest types of religious texts to appear were topographical lists. These provided a list of deities and their cult places, with their functions and attributes indicated via epithets. Some of these epithets, such as Horus’s “protector of his father,” suggest that certain myths were already developed even though we have no written record of them from this early period. There was certainly a tradition of oral transmission that was already old by the time the Great Pyramid was built.

With more than 1,500 named deities, it is far beyond our scope here to discuss more than a fraction of them. Instead, below is a brief discussion of a few selected deities of various types to serve as a basic introduction to the Egyptian pantheon.

Ra / Amun-Ra

Arguably the most important deity in Egypt was the sun god Ra. He merged with other solar deities at an early date and assimilated them as aspects of himself—he was the emergent Khepri at dawn, Ra-Horakhti as the midday sun, and the weary Atum at the end of the day. Ra was a universal deity, who acted in the celestial, terrestrial, and netherworld realms, and was often presented as the supreme creator who emerged from the primordial waters at the beginning of time. As creator of the world, Ra was also the archetypal ruler of the cosmos; myths tell of how he reigned over the earth until he became weary of the task and departed for the heavens, leaving living kings, known by the title ‘Son of Ra,’ to rule in his stead.

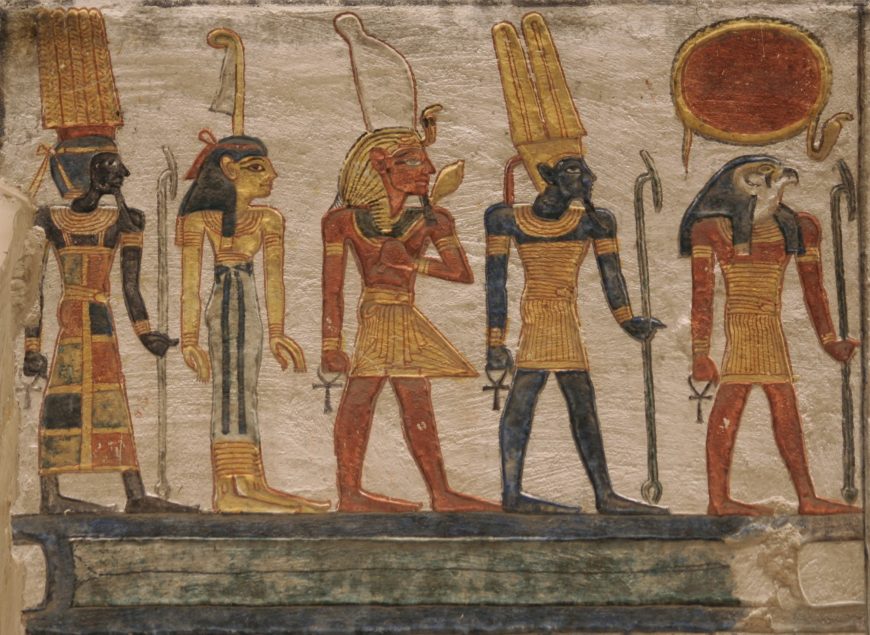

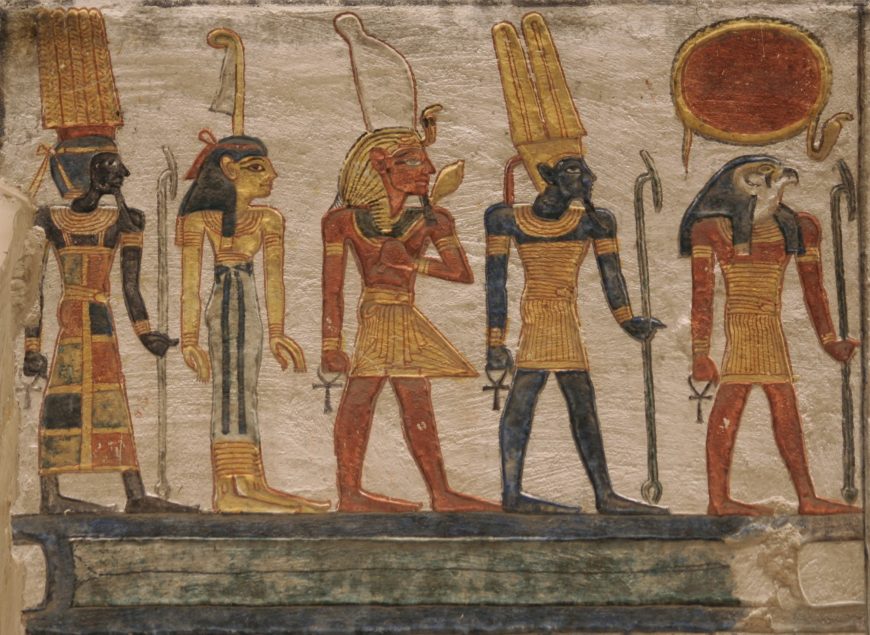

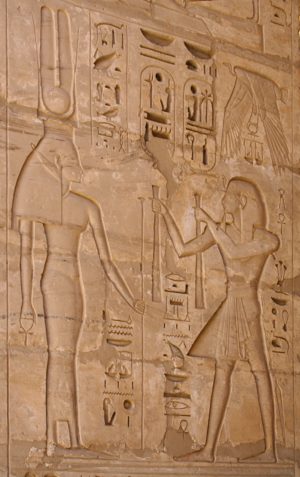

Ra-Horakhti, Amun, the deified king, Ma’at, and Andjeti in the tomb of Ramses V/VI (KV9)

When the god Amun rose in prominence in the New Kingdom, the two were fused to create the all-powerful Amun-Ra. His daily journey through the sky was fraught with dangers and he was accompanied in his sky boat by various deities who helped him on his path. In the Pyramid Texts, the king was said to join the entourage on the solar barque upon his ascension. His solar barque traveled the netherworld at night, passing through many challenges and merging with Osiris in the depths of the netherworld before emerging reborn at dawn.

As befitting a deity with so many aspects, Ra could be presented in many different forms, often simply as a sun disc wrapped with a protective cobra, but also in hybrid form as a male with a falcon, ram, or scarab head crowned by a sun disc. He was also manifested as various animals and could be represented as a ram, heron, serpent, bull, scarab beetle, lion, or cat (among other creatures, depending on the context). Iconographic devices, such as rows of discs and yellow bands displayed at the tops of walls or on ceilings, defined the symbolic path of the sun in temples and tombs. Solar symbols were integrated into many architectural forms as well; pyramids and obelisks were among the most prominent, but more subtle solar iconography was woven into nearly every Egyptian context.

Hathor

Hathor at the Memorial Temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu (Dynasty 20)

Hathor originated in the Predynastic period. She appears in the Pyramid Texts and later religious literature and holds a prominent place in the pantheon. Her name was written as Hwt-Hor, or “Mansion of Horus.” A sky goddess, Hathor was sometimes depicted in bovine form. Her main cult center was at Dendera, where a massive temple from the Ptolemaic period still stands, but she was worshiped in many locations throughout Egypt. She was connected to Ra as a strong, protective force, serving as an “Eye of Ra.” This role, which could be filled by several powerful goddesses, represented the dangerous aspects of the sun’s heat and helped to protect him. Sometimes, she was referred to as Ra’s consort who accompanied him on his daily journey through the sky. Called the “Golden One,” she usually wears a crown of a sun disk flanked with upright horns.

Also connected with sexuality, fertility, and motherhood, Hathor was the “beautiful one” who assisted women in all these realms. Most often represented in anthropomorphic form and wearing a red or turquoise dress, she was the mistress of the West who opened the gates of the underworld for the newly deceased and aided their transition. She was also presented as a hybrid figure with a human body and cow or composite head.

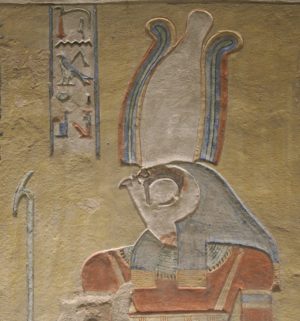

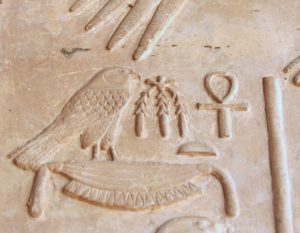

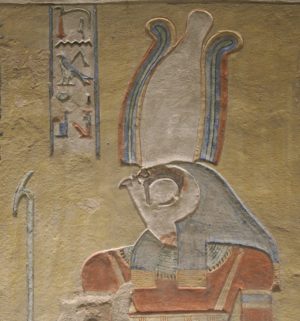

Horus in the tomb of a son of Ramses III in the Valley of the Queens (QV44)

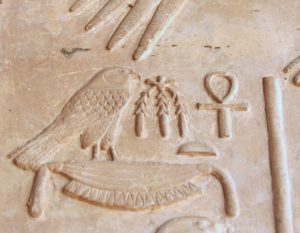

Horus

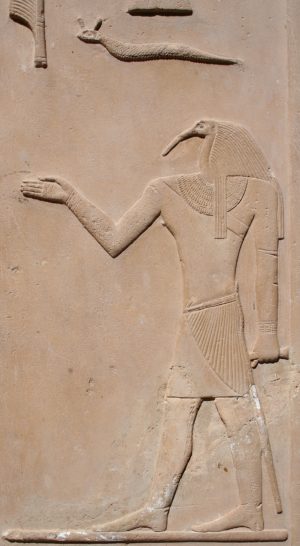

This falcon god was among the oldest known—Predynastic rulers were called ‘Followers of Horus’ in later texts and he appears on early ceremonial objects like the Narmer Palette. His complex nature is evident from the various aspects and roles he played in myth. Called ‘Lord of the Sky,’ Horus was viewed as a celestial falcon; these birds were highly revered for their sharp-eyed capabilities. This aspect was probably the earliest form in which he was worshiped, such as at the site of Hierakonpolis. Connected to this was his role as a solar deity and he was called Horakhty or “Horus of the two horizons’ as god of the rising and setting sun. Horus came to be worshiped as the son of Osiris and Isis, although the origins of this connection are obscure. In both falcon form and as the divine son of Osiris and Isis, Horus was strongly associated with kingship—kings were often referred to as a “living Horus.”

Diorite statue of King Khafre (Chephren), 4th Dynasty, Old Kingdom, Giza, Egypt (photo: kairoinfo4u, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

From the Early Dynastic period, the king’s name was written in a rectilinear form, known as a serekh, which was topped with a falcon. His role as guardian of kingship is beautifully demonstrated in the famous statue of an enthroned Khafre with the Horus falcon wrapped protectively around the back of his head.

As son of Osiris and Isis, Horus was heir to the mythical throne of Egypt and in pharaonic ideology the living king became associated with the falcon god while his deceased predecessor became Osiris, Lord of the Underworld. Horus was depicted in several forms: zoomorphically as a falcon, anthropomorphically as an adult or child god, and, most commonly, as a hybrid of a falcon-headed male wearing the Double Crown, signifying his rule over a united Egypt.

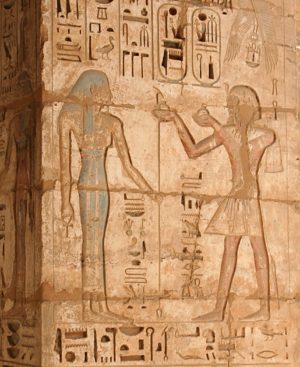

Osiris

Osiris in the tomb of a son of Ramses III in the Valley of the Queens (QV44)

One of the most important of all Egyptian deities, Osiris was prominent in pharaonic ideology and also popular in religion. He probably originated as a fertility god and was associated with the Nile inundations that rejuvenated the land. Viewed as a ruler of Egypt in the most ancient period, stories tell of his chaotic brother Seth slaying and dismembering him, scattering those pieces throughout the land. His powerful consort, Isis, gathered those pieces together and created the first mummy. Through her formidable magic, she revivified him and conceived their miraculous son, Horus. Horus avenged his father and Osiris became the King of the Underworld, providing a model for the desired resurrection that was the goal of every Egyptian.

In royal ideology, the deceased king was associated with Osiris while his living heir was viewed as the new Horus on the throne. Dwelling in the depths of the netherworld, Osiris served an essential role in the daily rejuvenation of the sun god Ra; he was even viewed as a counterpart of Ra for the dead, bringing them renewed life. Usually represented anthropomorphically as a shrouded wrapped mummy, often with green or black skin to suggest fertility, and grasping icons of kingship—the crook and flail.

He is often shown wearing a special crown called an Atef, which looks like a White Crown flanked by feathers. He is connected with the djed pillar from an early date; this hieroglyph came to be viewed as the stable backbone of the god. He served as the judge of the dead, sitting enthroned and viewing the weighing of the heart that awaited each deceased Egyptian. Eventually, the dead of all classes were referred to as an “Osiris.”

Isis

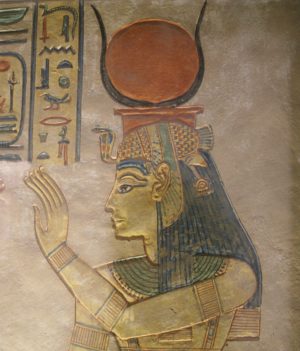

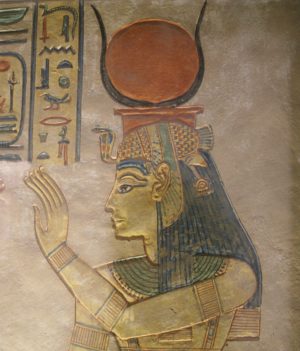

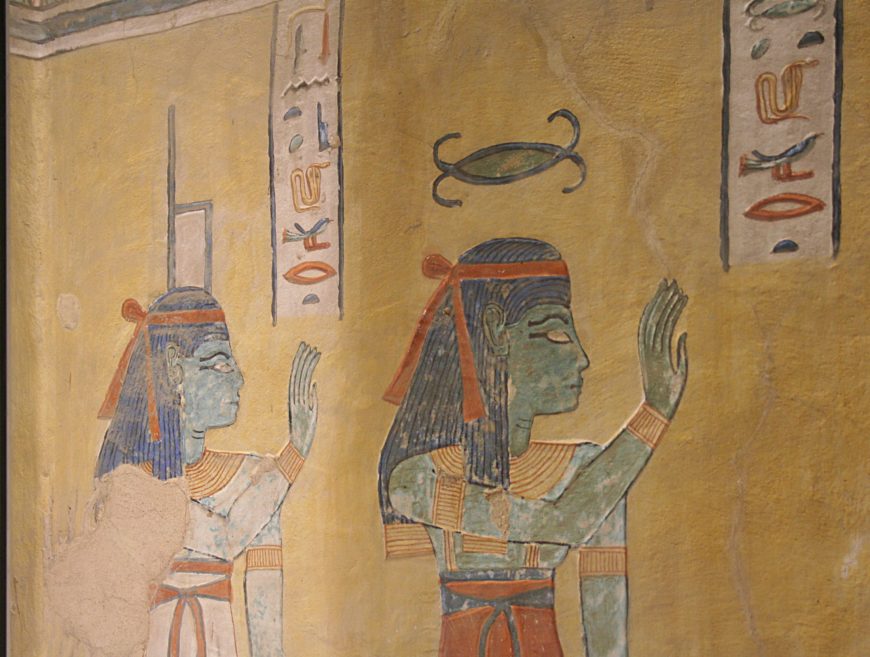

Isis in the tomb of a son of Ramses III in the Valley of the Queens (QV55)

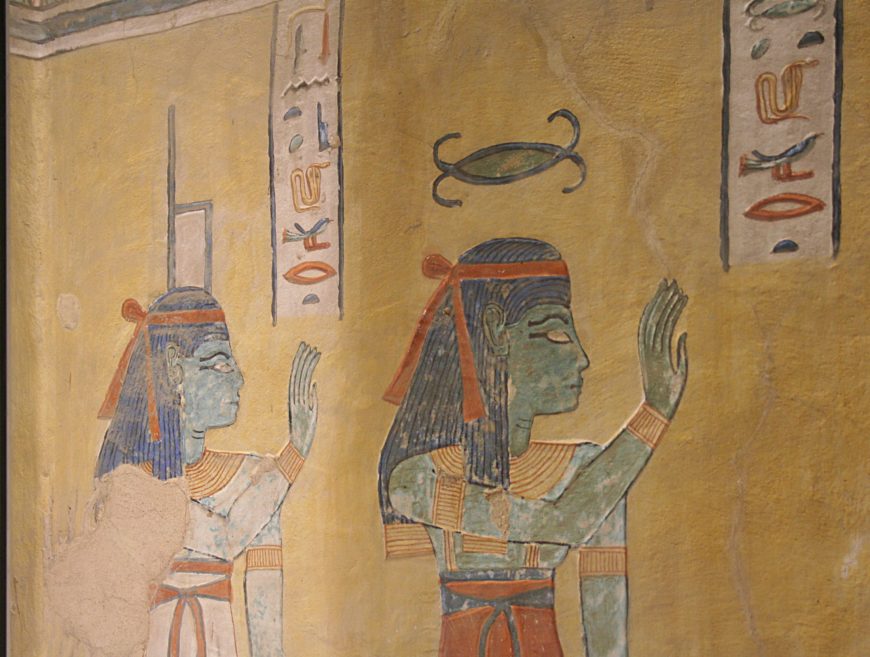

Almost always shown in anthropomorphic form, Isis was an extremely important goddess in Egypt and beyond. Sister-wife of Osiris, she appears more than 80 times in the Pyramid Texts assisting the deceased. She and her sister Nephthys were associated with kites (a scavenging bird of prey that has a shrill cry); they were portrayed as the archetypal mourners of the deceased. The primary protector of Horus, literally hundreds of thousands of statues were produced showing her holding the infant Horus on her lap.

Isis was the symbolic mother of the king and she may have originated as a personification of the power of the throne—her name is written with the sign for “throne’”and she is often crowned with this emblem. Like several other powerful goddesses, Isis could serve as an “Eye of Ra.” She was ‘Great of magic’ and her abilities in this realm are often emphasized. In addition to using her powerful magic to revivify Osiris and enact the conception of Horus, another story relays how she used her magic to heal Horus from a scorpion sting. She was often invoked in spells of protection and healing. One fascinating myth tells of how she used magic to learn the secret name of Ra, gaining dominance over him by that knowledge. On her head, Isis usually wears either the throne hieroglyph or a sun disc and horns. Sometimes she has wings, especially when her arms are outstretched to protect the figure of Osiris. A protective amulet associated with Isis, called a tyet, was used by the living and also often placed in mummy wrappings.

Her famous temple on the island of Philae was the last functioning Egyptian temple and her worship there continued until the 6th century C.E. Isis’s influence outside of Egypt (such as in ancient Rome) was substantial. She was connected with other goddesses, such as Astarte and Aphrodite, and had temples at Byblos, Athens, and Rome. Her cult was one of the “mystery religions” practiced throughout the Greco-Roman world; evidence of her veneration has been discovered as far away as England.

Ma’at

This goddess personified the concepts of justice, truth, and cosmic order and is generally represented in anthropomorphic form wearing a tall feather on her head. She existed from as early as the Old Kingdom and appears in the Pyramid Texts. She was associated with Ra and also Osiris, who was called ‘lord of ma’at,’ and was generally identified as the consort of Thoth. Ma’at’s connection to the king was vital — the ruler gained legitimacy through their capabilities in maintaining cosmic balance and they were often called ‘beloved of Ma’at.’

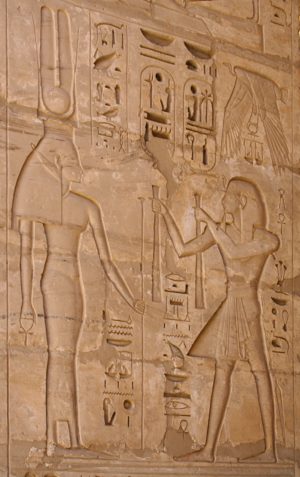

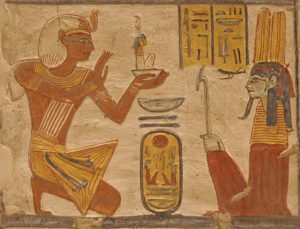

Ma’at being offered by the king to Amun-Ra, King of the Gods, in the tomb of Ramses V/VI (KV9)

Many images show the king presenting a small figure of Ma’at to other gods, especially Amun, Ra, and Ptah, as an affirmation of the ruler’s ability to maintain order and also as sustenance for the gods similar to food offerings; some texts explicitly state that the gods ‘live on Ma’at.’ She also represented judgment and the feather of Ma’at was placed opposite the heart of the deceased on the scales at their final judgment. If the heart was heavier than the feather, the deceased was truly damned; if the heart was lighter than the feather of truth, the blessed dead could enter an idealized afterlife in the Field of Reeds.

Amun wearing his two-feather crown on the White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak

Amun

Amun was first mentioned in the Pyramid Texts along with his consort, Amunet, and the pair were also part of the Ogdoad representing the element of “hiddenness.” He became the primary local god of the Theban region during the 11th Dynasty, with a series of kings who took the name Amenemhat (Amun is pre-eminent), and eventually rose to the supreme position in the pantheon during the New Kingdom, having been merged with the sun god as Amun-Ra. His early shrine at Karnak expanded greatly over time and became the largest religious complex on the planet. He was associated with the goddess Mut and the moon god Khonsu was worshiped as their son. Although grouped as the Theban Triad, each had their own sacred spaces within the Karnak complex.

Not only part of the Ogdoad, Amun was also represented as a primary creator god and his Karnak temple was said to house the “mound of the beginning,” where he brought the world into being. He was associated with the sun as Amun-Ra and was also viewed as a powerful fertility god. In this aspect, he was called ‘Amun-Min kamutef’ (literally “bull of his mother,” suggesting he begot himself with the sky cow goddess) and was depicted in ithyphallic form in many ritual scenes at Karnak and Luxor temples. Amun was first called “king of the gods” on the White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak and this title became commonly applied to him. In later periods, he was associated with the Greek god Zeus. Regularly depicted in anthropomorphic form with blue skin, he was shown wearing a short kilt, bull tail, and a crown with a flat-topped base and a pair of tall feathers. He was also shown in hybrid form with a human body and the head of a ram with curved horns.

Mut in the Memorial Temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu (Dynasty 20)

Mut

Although her origins are unclear and the first certain mention of her doesn’t occur until the end of the Middle Kingdom, Mut became the great mother goddess and queen of the gods from the New Kingdom onwards. She replaced Amunet, Amun’s original consort from the Ogdoad, and became his chief wife. Her name was written as a vulture, the word mwt which meant “mother,” and she was usually identified with the living queen as mother of the king.

The vulture headdress commonly worn by Egyptian queens is a reference to Mut. Atop her vulture headdress, Mut is often shown in anthropomorphic form wearing the Double Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt and holding a papyrus topped staff. She was also closely connected with the lioness, especially in her fierce aspect as a protective “Eye of Ra,” and was sometimes portrayed with a leonine head. She had a connection with violent justice as well; a fearsome punishment of fire in the “Brazier of Mut” awaited any rebels or traitors to the throne. Generally, her influence was focused on the world of the living and she played little role in the afterlife; there is evidence for a great deal of personal veneration of this “Great Mother” by the population.

Seth

Seth is seen on this loose block housed in the Open Air Museum at Karnak Temple

Originally a desert deity, Seth represented chaotic and destructive forces. Sometimes paired with the falcon god Horus, he appears on Predynastic objects and also figures prominently in the Pyramid Texts. By the Middle Kingdom, he had assumed a position on the front of the solar boat to help repel the chaos serpent Apophis that threatened the sun god’s daily journey. Seth was depicted as an enigmatic long nosed canid with squared ears and an upright forked tail or as a hybrid of a human body with the head of this animal. His title ‘Red One’ linked him to the desert lands as did his wild temperament; in general, he was linked with violence, conflict, and rebellion. Seth stood in opposition to his brother Osiris, who represented the fertile ‘Black Land’ of the Nile valley. According to myth, Seth murdered his brother and tore his body into pieces. Later, he struggled in a series of conflicts with Horus, the son of Osiris and Isis, engaging in vicious acts including tearing out Horus’s eye. Eventually, Horus triumphed over his uncle and claimed the throne. Seth’s fearsome character came to be associated with storms, sickness, disease, crime, foreign invasion, and other evils in the world.

Anubis

An early, important funerary deity, Anubis was connected with burial and afterlife—he is mentioned dozens of times in the Pyramid Texts in this capacity. He fulfilled this role for all deceased Egyptians, presiding over mummification and protecting burials. He was placated in the hope that he would control the scavenging desert dogs who had the habit of digging up shallow graves and scattering the bodies; a horrific fate for any Egyptian.

Anubis in the tomb of a son of Ramses III in the Valley of the Queens (QV44)

Usually depicted as a black canid or a human with a jackal head, his black coloration was symbolic of regeneration. Anubis was called ‘Foremost of the Westerners’ (i.e. those in the land of the dead) and ‘Lord of the Sacred Land’ signifying his supremacy over the desert cemeteries. Often depicted attending the mummy in its tomb (a role that may have been played in the terrestrial realm by human priests wearing jackal masks, several of which survive), he was called ‘Master of Secrets’ due to his connection with embalming. One of his main functions was to lead the deceased before Osiris and perform the Weighing of the Heart at their final judgment.

Ptah

One of the oldest gods, attested as early as the First Dynasty. His primary cultic location was Memphis, which was the administrative seat for most of Egypt’s history.

Ptah and Sakhmet at the Temple of Seti I at Abydos

Generally represented in anthropomorphic or mummiform wearing a blue cap crown, his consort was the fierce lion-headed goddess Sakhmet. The god of craftsmen, Ptah was a chthonic creator being, sometimes called “the sculptor of the earth.” He is usually shown as mummiform, connecting him with funerary and afterlife realms, often standing on a small base in the form of the hieroglyph for ma’at, or “truth.” Ptah was venerated as far south as Nubia and his image is one of four sculpted at the rear of the temple of Ramses II at Abu Simbel along with the deified king, Amun-Ra, and Ra-Horakhti. This temple was designed so that twice a year the rays of the rising sun penetrated deep into the temple and illuminated this group statue. However, while the sun lights up the other three images, the creator god Ptah stays forever in darkness.

Sakhmet

A fierce leonine goddess, Sakhmet had two distinct sides to her personality—she could either be destructive and dangerous or aggressively protective. She was the quintessential ‘Eye of Ra’ who protected her father, the sun god, from his enemies. Sakhmet was also his preferred instrument of destruction. One myth tells of a time when Ra became tired of humans plotting against him and he sent his ferocious daughter to punish them; she became so blood-thirsty and enamored with her task that she nearly brought about the complete destruction of humanity before the other gods were able to reign her in (by getting her drunk with red-dyed beer she mistook for pool of blood). Sakhmet was said to breathe fire at her enemies and she became the primary protector of the king, especially in battle. However, her breath was also capable of bringing pestilence—Sakhmet had to be propitiated and a special ritual known as ‘appeasing Sakhmet’ was performed to combat epidemics. If she was appeased, she could bring healing instead of plague. Amenhotep III commissioned hundreds of black granite statues of the goddess to be set up in temples around Thebes in an apparent attempt to keep her happy. Usually regarded as the consort of Ptah and worshiped primarily at Memphis, she also had temples in many other areas. Sakhmet was usually represented in hybrid form as a woman in a red dress with the head of a lioness (see the image directly above) wearing a long wig and sun disc atop her head.

Neith

An ancient goddess, Neith appears to have been one of the most important prehistoric deities and her worship extended to the very end of Egypt’s history. Her mythology is complex.

Neith and Isis in the tomb of a son of Ramses III in the Valley of the Queens (QV44)

She was a warrior goddess, associated with hunting, weapons, and warfare—one of her earliest emblems includes a pair of crossed arrows atop a pole—and she served as an ‘Eye of Ra.’ Much later, she was connected with the Greek goddess Athena. She also had a creator aspect and was part of the primeval waters; some texts even describe her as creating Ra and humankind calling her ‘the eldest, mother of the gods.’ As such, she was also seen as an archetypal mother figure and was said to support women in childbirth. Her connections to Lower Egypt are evident by the regular representations of her as an anthropomorphic female wearing the Red Crown. Her other common identifying headgear was the distinctive symbol that was used for her name. A funerary deity who protected the deceased, she was also believed to be the inventor of weaving and provider of mummy bandages and shrouds.

Nut

Nut being presented with wine by Ramses III at his Memorial Temple at Medinet Habu

Personification of the sky, Nut was a member of the Ennead and daughter of Shu and Tefnut. She was the mother of heavenly bodies, who swallowed the sun each night and birthed the disc again each morning. In this cosmic view, the sun god traveled through her body each night and the stars were similarly absorbed during the day. She may have been specifically associated with the Milky Way, stretched across the heavens. Given the perceived solar journey, it is not surprising that Nut became closely connected with the concept of rebirth. From early in Egypt’s history, she also served this function for the deceased and is mentioned nearly 100 times in the Pyramid Texts as an agent of resurrection.

She was often portrayed frontally and outstretched on the interior lids of coffins and sarcophagi to aid in this process. Nut is generally shown in anthropomorphic form, sometimes with a water pot on her head, but could also be represented as a sky cow, with her four hooves being the cardinal points and the stars and sun god sailing across her belly. In anthropomorphic form, she is often shown nude and in profile in relief, with her body arched over the earth god Geb and her body full of stars. Some of the most magnificent representations of her appear on the ceiling of the burial chamber of the tomb of Ramses VI in the Valley of the Kings where a pair of colossal images were painted back to back. These represent the day and night sky and show the sun disc making its journey through her body to emerge at dawn.

Seshat follows behind the king and records millions of years for his reign. Memorial Temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu

Seshat

The goddess of writing, accounting, and notation, the “female scribe” (as her name is translated) was patroness of temple libraries. Beginning from the 2nd Dynasty, Seshat was responsible for establishing the ground plan in the foundation of sacred structures and was called the “mistress of builders.” She also kept records of the booty and tribute taken by the throne as well as being responsible for tracking the king’s regnal years and jubilee festivals, which she inscribed on palm ribs and the leaves of a sacred tree.

She was shown in anthropomorphic form as a woman wearing a leopard skin dress and an enigmatic symbol on her head that resembles a seven pointed star topped by a crescent shape.

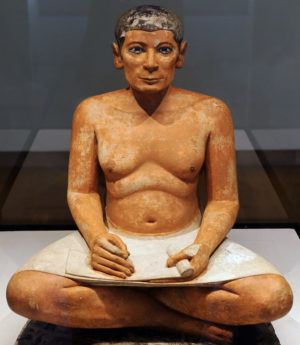

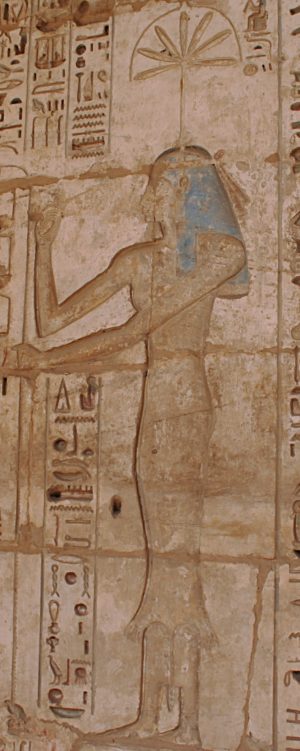

Thoth

Thoth with his ibis-head on the White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak

Originally a moon god, Thoth came to be associated with knowledge and was said to have invented writing. Shrewd and skilled, he became connected with scribes and scholars. He kept records for the gods, acting as their scribe, and also served as the patron for all areas of written knowledge. Many temple scenes show him recording the events that are depicted or tallying the offerings being presented. In the afterlife, he stood next to the scales that weighed the heart of the deceased and recorded the verdict.

Widely venerated, Thoth was worshiped in many areas of Egypt and the many thousands of votive ibis mummies discovered in these cult locations illustrate his popular appeal. Viewed as truthful and straightforward, Thoth was usually represented in hybrid form with a male body and head of an ibis. He could also be depicted in animal form as an ibis and also as a baboon, sometimes crowned with a lunar disc and crescent. Mentioned frequently in the Pyramid Texts, often in association with Ra, Thoth was sometimes referred to as the ‘night sun’ in juxtaposition with the solar deity. Through his knowledge and magical abilities, he was said to have healed the eye of Horus after Seth plucked it out. He often acted as an intercessor and messenger between the gods; in later times, he was associated with the Greek god Hermes.

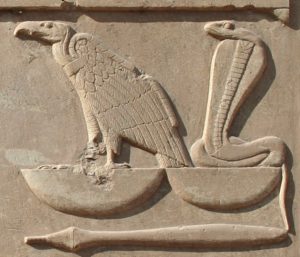

Nekhbet

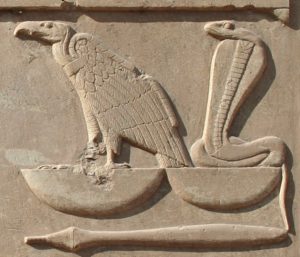

Nekhbet and Wadjet in fused form on a lintel at Karnak Temple

This vulture goddess was the tutelary deity of Upper Egypt. She and the cobra goddess Wadjet, who was connected with Lower Egypt, were the Two Ladies — together, they represented the united Egypt. Nekhbet was usually depicted wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt and she was considered a mother of the king. Almost always represented as a vulture with her wings outstretched, she often frames the shen sign of eternity between her wings or grasped in her talons.

Wadjet

Connected with the delta region of Lower Egypt from the earliest times, the cobra goddess Wadjet (‘the Green One’) was paired with the vulture Nekhbet to signify the Two Lands. She was closely linked with the king as a fierce protector — ‘Mistress of Fear,’ she was the ubiquitous cobra perched on the king’s brow who spat fire at his enemies. She also protected the gods; even during the Amarna period when many other deities were avoided, she was shown as a protective element on the sun disc itself. Almost always depicted as an upright cobra, Wadjet was sometimes fused iconographically with Nekhbet as a vulture with a cobra head.

Cosmetic jar in the form of Bes, Late Period (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Bes

This complex and enigmatic figure may really represent a series of supernatural beings that were eventually merged. Although little is known about his origins, Bes became one of the most popular and widespread of Egyptian deities. By the New Kingdom, he was accepted by all classes of society as a fiercely apotropaic being who was especially connected with the protection of pregnant women, women in childbirth, and young children. He was often represented alongside the goddess Taweret in this role.

His appearance is unique and seems to have originated in the form of a dwarf wearing a lion skin or as a lion standing upright on its rear paws. He is usually portrayed frontally, even in relief, as a squat figure with short legs, a tail, and an enlarged head with a lion mane and a projecting, lolling tongue. He often wears a plumed headdress. Regularly depicted in amuletic form or carved on cosmetic items, musical instruments, apotropaic wands, headrests, and beds, his fierce protective image also appeared painted in rooms of royal palaces and even on the king’s chariots. Bes was widely venerated in household shrines and his popularity spread well beyond Egypt, appearing in Cyrus and Assyria.

Taweret

Tawaret is included in an astronomical ceiling in the tomb of Ramses V_VI (KV9)

The “Great female one,” Taweret appeared as early as the Old Kingdom. She is usually represented as a hippopotamus standing upright with a swollen, pregnant belly and pendulous breasts and the paws of a lion. Often, her mouth is open in a wide grimace, emphasizing her protective function and she usually wears a long wig with a flat modius crown, feathers, or a sun disc with horns.

Protector of pregnant women, her primary attributes are the ankh, symbol of life, and the sa, emblem of protection, which were usually oversized and placed at her sides with her paws resting on the top. One of the most popular household deities and commonly revered in household shrines, Taweret seems to have had no formal temple cult. She was often paired with Bes and also appears on headrests, cosmetic items, apotropaic wands, and amulets.

Hapy fecundity figure carrrying the bounty of the land. Temple of Ramses II at Abydos (Dynasty 19)

Hapy

The personification of the river Nile, particularly related to the annual inundation and the fertility it brought. A manifestation of divine order, Hapy was referred to as a creator god that helped maintain cosmic balance. This deity was the ‘Lord of the fishes and fowl,’ with many riverine forces being portrayed as their attendants. Usually depicted androgynously or as a male with a swollen belly and pendulous breasts, Hapy displayed a clump of papyrus and lotus clusters on their head.

Often represented with blue or green skin, sometimes with wavy water signs carved into the flesh. Hapy is shown on colossal statues of the king as twinned figures tying together the heraldic plants of Upper and Lower Egypt around the sema hieroglyph representing ‘union.’ Rows of Hapy figures often appear in temple relief bringing the bounty of the land as offerings.

Mummification and Funeral Rites

Mummy of Herakleides, 120–140 C.E., Romano-Egyptian, human and bird remains; linen, pigment, beeswax, gold, and wood, 175.3 x 44 x 33 cm (Getty Villa, Los Angeles; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Little evokes ancient Egypt more quickly for more people than mummies. Over the millennia, scores of them have been unearthed and these complex echoes from the past have been handled in very different ways during that time. Often viewed more as artifacts and curios rather than as human remains, they were ground to powder for use in medicinal concoctions for many centuries (and, later, oil paints!), sometimes burned unceremoniously as fuel, and unwrapped with great fanfare at fashionable parties in the Victorian era. Today, mummies are treated with far greater respect and have provided deep insights and a vast amount of information about these ancient people, but their display and presentation remains a controversial topic.

The earliest burials known from Egypt were simple pits scooped out of the desert sand. These contained the bodies of the deceased, usually curled on their side in a fetal position, and often included objects of daily life such as pots, beads, tools, and other small items. Dated prior to the time of unification (well before 3000 B.C.E.), early cemeteries were located along the edge of the desert near settlements, the desert west of the Nile was already considered the land of the dead. Over time, the continued existence of the body on earth came to be viewed as essential for a successful afterlife. The physical corpse (or an inscribed image, or even one’s written name) served as a conduit with earth that allowed sustenance from offerings and magical spells included in the tomb or inscribed on its walls to flow to the deceased in the netherworld. Given the importance placed on the body, it is not surprising that the art of mummification developed to such an exceptional degree. There was a huge range of experimentation that occurred over Egypt’s long history of mummification, some techniques being far more successful than others.

Mummification

Sadly, no step-by-step guide to mummification has yet been discovered. Some 3rd–1st century B.C.E. papyri record wrapping instructions, amulet placement, and some spells, but the most detailed textual description of the process comes from the 5th-century B.C.E. Greek historian Herodotus in Book II of his Histories. He describes three different types of embalming, varying in expense, complexity, and quality of result.

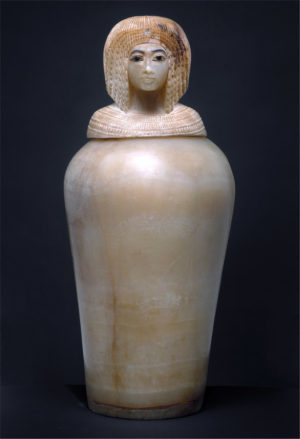

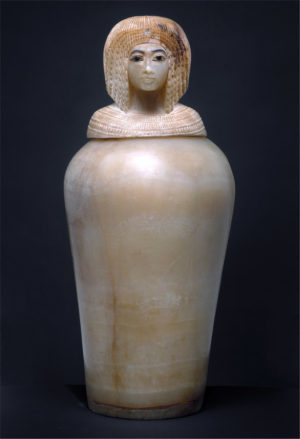

Canopic Jar with a Lid in the Shape of a Royal Woman’s Head, c. 1352–1336 B.C.E., reign of Akhenaten, Dynasty 18, New Kingdom, Amarna Period Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes, Valley of the Kings, Tomb KV 55, Davis/Ayrton 1907 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In its full-fledged incarnation, the high-quality process of mummification took around 70 days and entailed:

-

Death Mask from innermost coffin, Tutankhamun’s tomb, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, c. 1323 B.C.E., gold with inlay of enamel and semiprecious stones (Egyptian Museum, Cairo, photo: Mark Fischer, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Removing the viscera (liver, lungs, intestines, and stomach) through an incision in the left side; these organs were mummified separately and placed in four canopic jars. The heart, considered the seat of intelligence, was usually left inside the body.

- The mysterious brain, a wet organ that encouraged putrification (which was anathema to the mummification process), was removed through the nostrils using a long metal hook and discarded.

- The body was washed with palm wine, dried, and then covered with natron (netjry, in ancient Egyptian, which translates to “divine salt”). This powdery salt, derived from an oasis near the delta called the Wadi Natrun, desiccated the body over a period of up to 40 days.

- Once dried out, the body was uncovered, ritually cleaned, and then anointed with fragrant oils and a thick coating of resin.

- Then the body was wrapped with many layers of linen strips—a process that could take more than two weeks. Between the layers, various amulets were placed in specific locations with the hopes that they would aid the deceased in their netherworld journey. In royal burials, precious jewelry and regalia were included in these layers; the intact mummy of Tutankhamun included more than 150 objects wrapped in his linen. When the wrapping was complete, the bandages were thoroughly soaked with liquified resin.

- To maintain the identity of the body, a mask could be placed on the mummy’s head. In later periods, a portrait was painted on a wood panel and inserted into the bandages. The mummy was then encased in a coffin, usually covered with amuletic scenes and texts that identified the deceased and provided them with the magical spells needed to safely traverse the dangerous netherworld.

, Romano-Egyptian, human and bird remains, linen, pigment, beeswax, and wood (The Getty Villa)” width=”870″ height=”489″ aria-describedby=”caption-attachment-63645″>

, Romano-Egyptian, human and bird remains, linen, pigment, beeswax, and wood (The Getty Villa)” width=”870″ height=”489″ aria-describedby=”caption-attachment-63645″>

Mummy with a portrait of Herakleides, 120–140 C.E., Romano-Egyptian, human and bird remains, linen, pigment, beeswax, and wood (The Getty Villa; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The mid-range method omitted steps, such as the incision and manual removal of the viscera, while the least expensive option entailed the body simply be washed, dried in natron, and then wrapped.

Mask likely to be worn by a male priest playing the part of Anubis in a temple during mummification or burial ritual. Probably buried with the priest who had worn it in life. Anubis mask, 8–4 B.C.E., cartonnage, coarse linen, mud plaster mixed with straw, probably excavated in Thebes, Egypt, 24 x 36 cm (Harrogate Museums and Arts)

Archeological evidence has provided a great deal of additional information about this complex process beyond what was written in antiquity. For instance, although there are no texts referring to the practice, numerous discoveries of caches of carefully buried used embalming materials have given valuable insight into the techniques used. Not much is known about the ancient embalmers, except that wrapping was typically performed by a special class of priests, one of whom seems to have been masked and performed as the god Anubis.

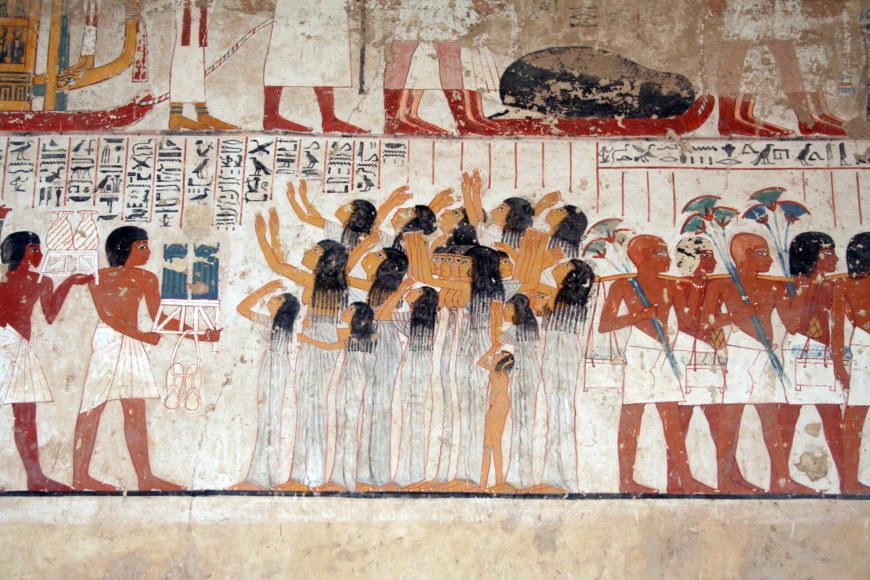

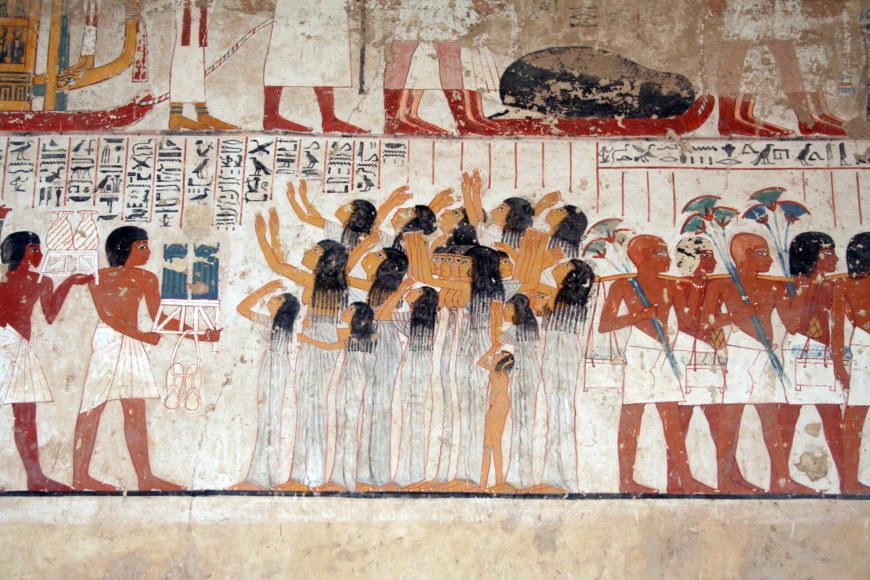

Mourners in the funerary procession of Ramose, Tomb of the Vizier Ramose (TT 55), Western Thebes, Dynasty 18. Note the white sandals and other grave goods being carried by figures around the mourners (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Funerary rites

Once the mummy was prepared, it was retrieved from the embalmers by the family. The mummy was placed in its prepared coffin and taken in procession to the tomb along with all the items destined to join the deceased in the afterlife. Included in this mournful group would be friends and family, along with priests to perform the funerary rituals and (if the deceased was wealthy) professional mourners who wailed and tore their clothing in anguish. Expressive tomb paintings of funerary processions show these figures with disheveled hair and tears streaming down their faces as they accompany the deceased on their final terrestrial journey.

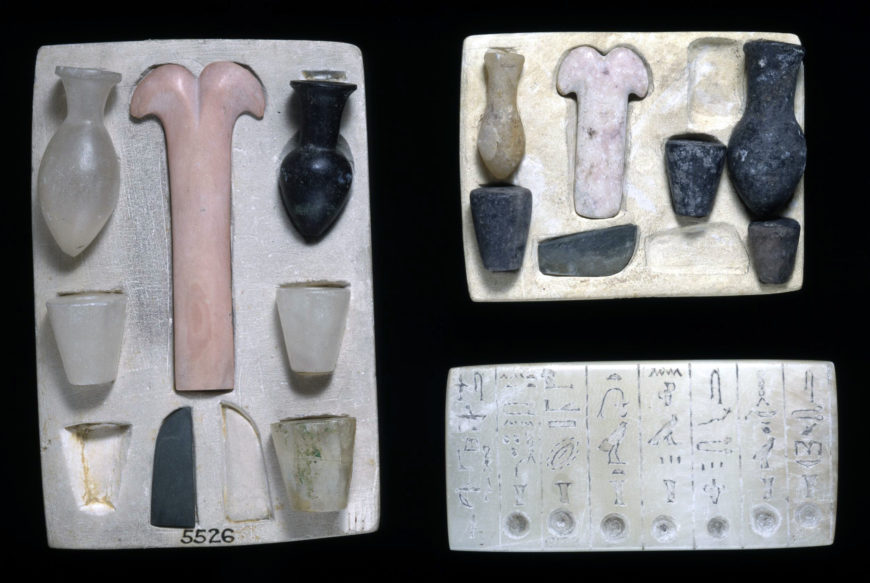

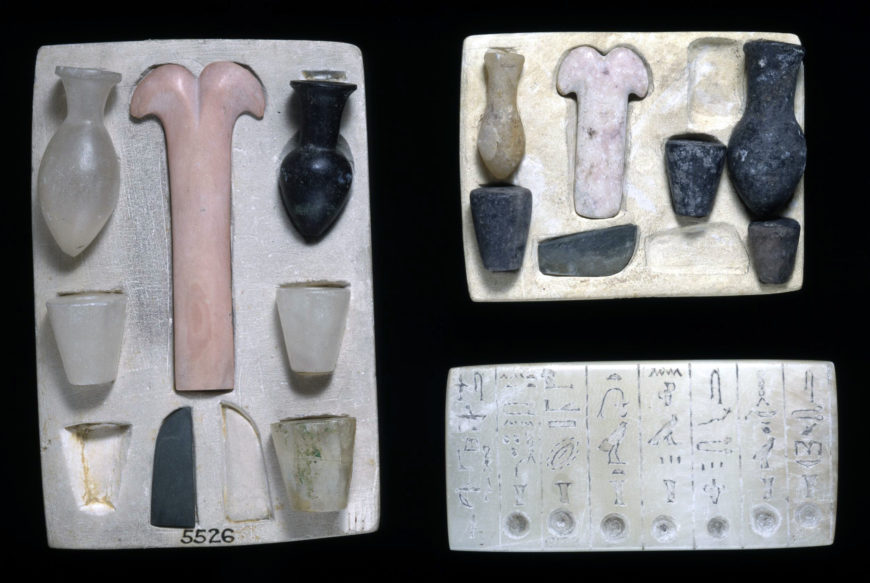

Model of equipment for Opening of Mouth Ceremony: five vessels (calcite and limestone), a small knife blade and a pesesh-kef implement (schist and limestone) set into depressions of limestone tablet, 6th dynasty, Egypt (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The last stage before burial was a special ceremony performed by the heir and a priest wearing a panther skin wrapped around their torso. This “Opening of the Mouth” ritual was considered essential as it allowed the deceased to fully engage in the afterlife. The ceremony involved touching the organs related to the senses—eyes, ears, nose, and mouth—with special instruments, such as an adze (a woodworking tool) and a double-forked knife called a pesesh-kef. It is fascinating to note that these instruments were related to those used during childbirth, like the pesesh-kef that was also used to cut the umbilical cord. These ritual actions allowed the mummy’s senses to become magically useful again and permitted the deceased to be a fully functional being and an effective akh in the afterlife.

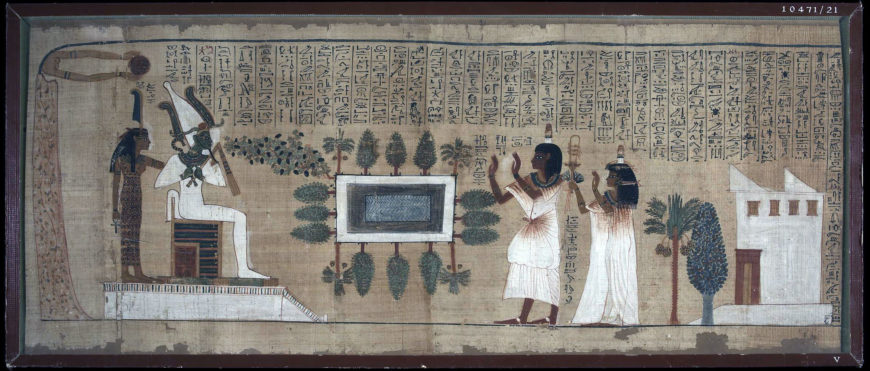

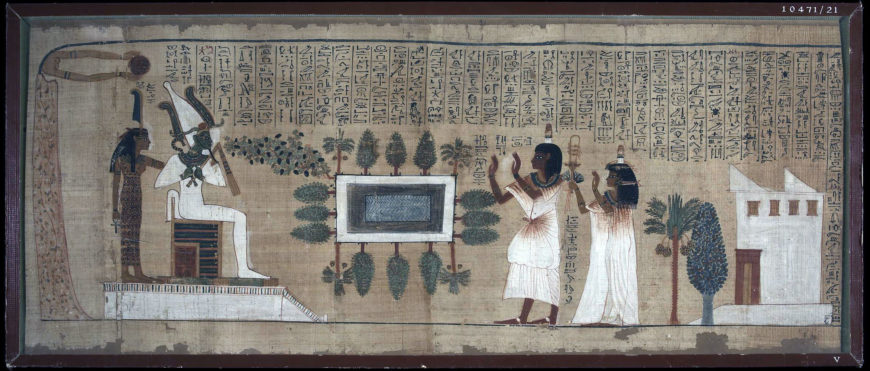

Once all the necessary rites had been completed, there was a funerary feast held in front of the tomb with the mummy, often draped in flower garlands, as guest of honor. Then, the mummy—along with its offerings and grave goods—was placed into the burial chamber and sealed away. This final act initiated the deceased’s passage into the netherworld, providing spells, guides, protective amulets, and tools in their tombs to aid them along that dangerous journey. Their eventual goal was to reach the idealized Field of Reeds (the Egyptian version of heaven) and enjoy an eternity in that place of perfection, sustained for all time through their terrestrial link to the tomb reliefs, grave goods, and ongoing offerings provided.

Although the living went back to their lives when they left the funeral, the deceased was far from forgotten. Regular festival occasions included visits to the tomb by family, sometimes with memorial picnics taking place in the area before the chapel, and gifts and offerings were left. Once a deceased Egyptian was perceived to have successfully navigated the dangerous pathways of the netherworld and achieved their place in the Field of Reeds, their living relatives and descendants would sometimes approach with petitions or requests for guidance. Often referred to as “Letters to the Dead,” these written requests for otherworldly intervention in the affairs of the living were usually written on small clay bowls filled with a food offering to entice the deceased spirit to help bring about the desired result.

For the ancient Egyptians, the dead were never truly forgotten. Even by speaking the name of an individual, the living helped guarantee eternal existence of that being in the afterlife.

Additional resources

A brief video outlining the mummification of a late Ptolemaic period man, including the layers of wrappings and how the portrait was inserted.

Introduction to Ancient Egyptian Mortuary Texts

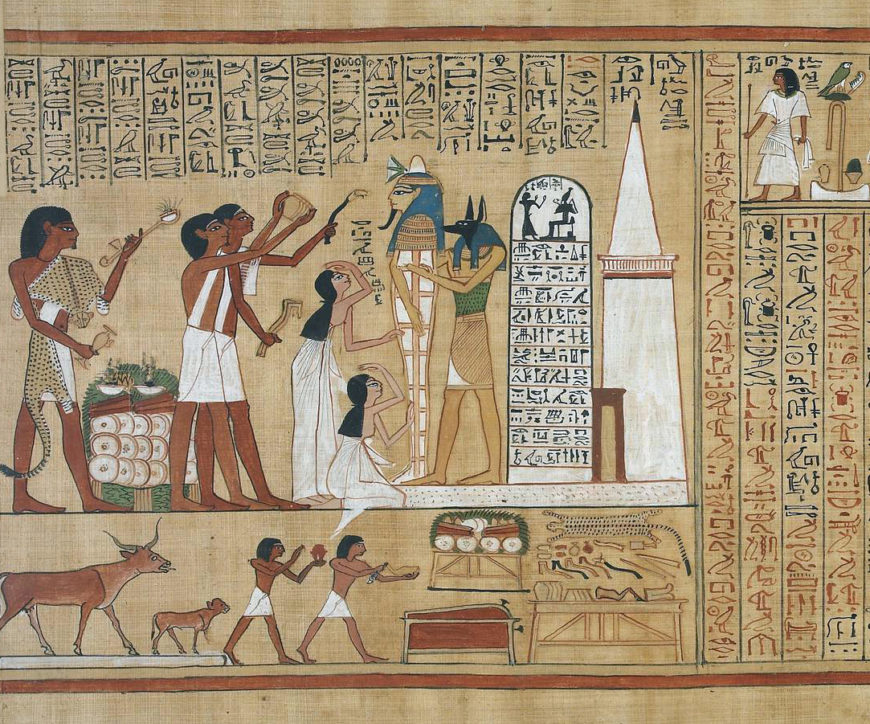

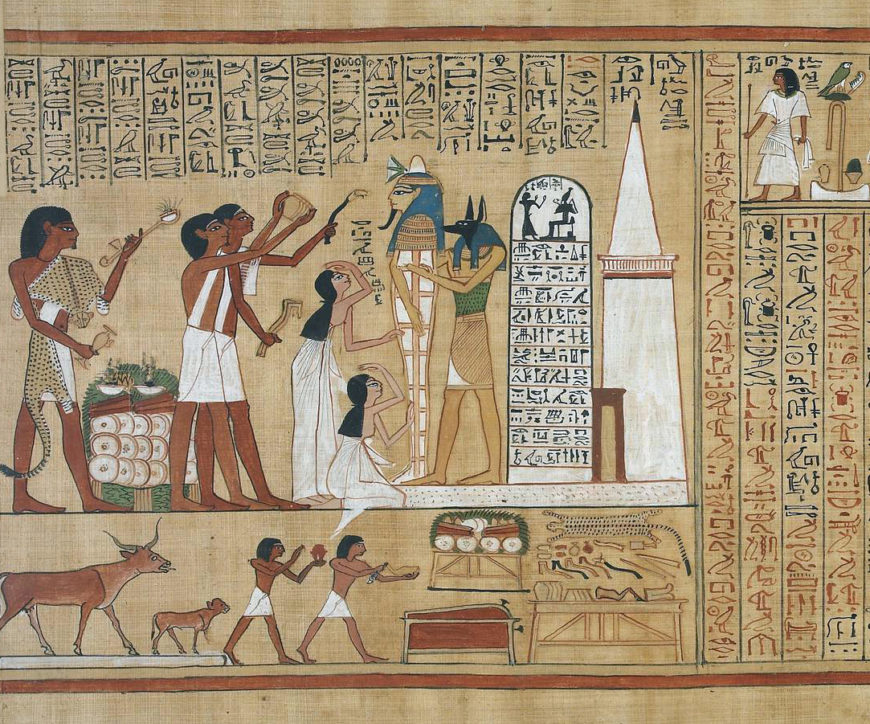

Page from the Book of the Dead of Hunefer, c. 1275 B.C.E., 45.7 x 83.4 cm (frame), Thebes, Egypt (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Given the number of tombs, mortuary temples, and funerary artifacts that have survived from ancient Egypt, it is not surprising that many people mistakenly believe that ancient Egyptian society was obsessed with death. This could not be further from the truth—the Egyptians were obsessed with life, and specifically the life they experienced in the Nile valley, which was viewed as the ideal existence on earth. Every Egyptian wanted the desired afterlife: an eternal, perfected, effortless version of life along the Nile, including a river teeming with abundant fish, fields overflowing with a variety of produce, and deserts full of animals to hunt.

A collection of rituals and texts

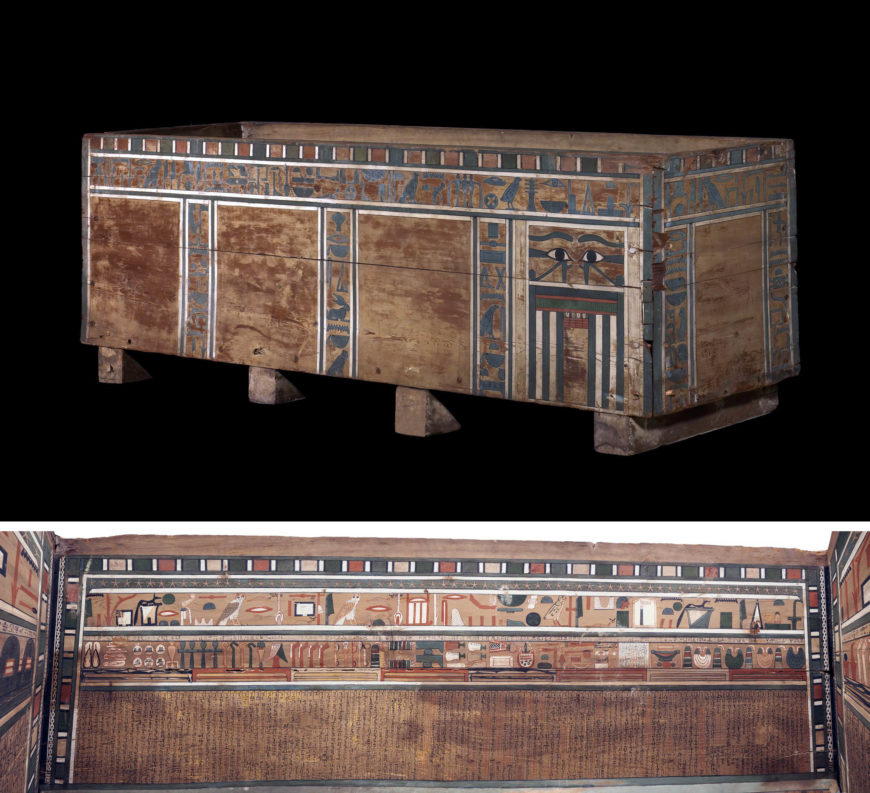

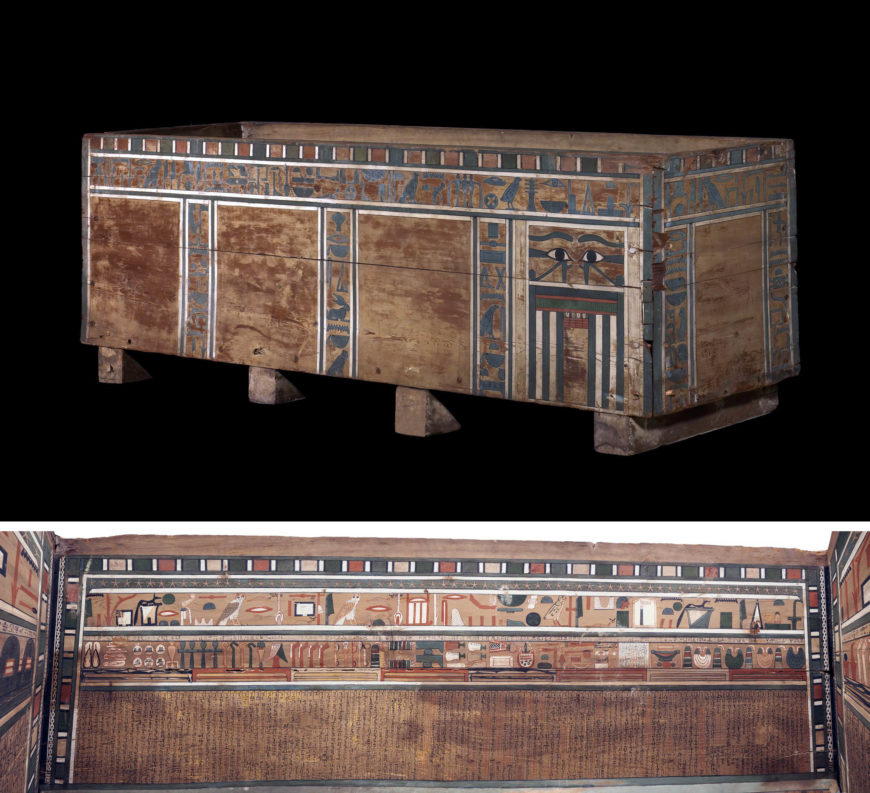

The earliest known burials at all social strata contained grave goods and offerings to provide for the deceased in the afterlife. From the Old Kingdom onwards, tombs—royal and non-royal alike—included chapels where the living could come to present offerings and perform ritual actions to support the deceased in their journey. Over time, a collection of rituals and texts developed that were specifically intended to help the deceased become an effective being in the afterlife. Modern scholars divided this collection into the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and Book of the Dead, largely aligning with periods of time (Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, and New Kingdom) and the most popular presentation of the texts (in pyramids, on coffins, or on papyri).

Despite the modern convention of dividing these texts, the ancient Egyptians viewed these compositions as a single continuum. By carving these essential spells on tomb walls or including them on coffins, papyri, and other objects, the goal was to ensure their eternal effectiveness in providing for the deceased in the afterlife.

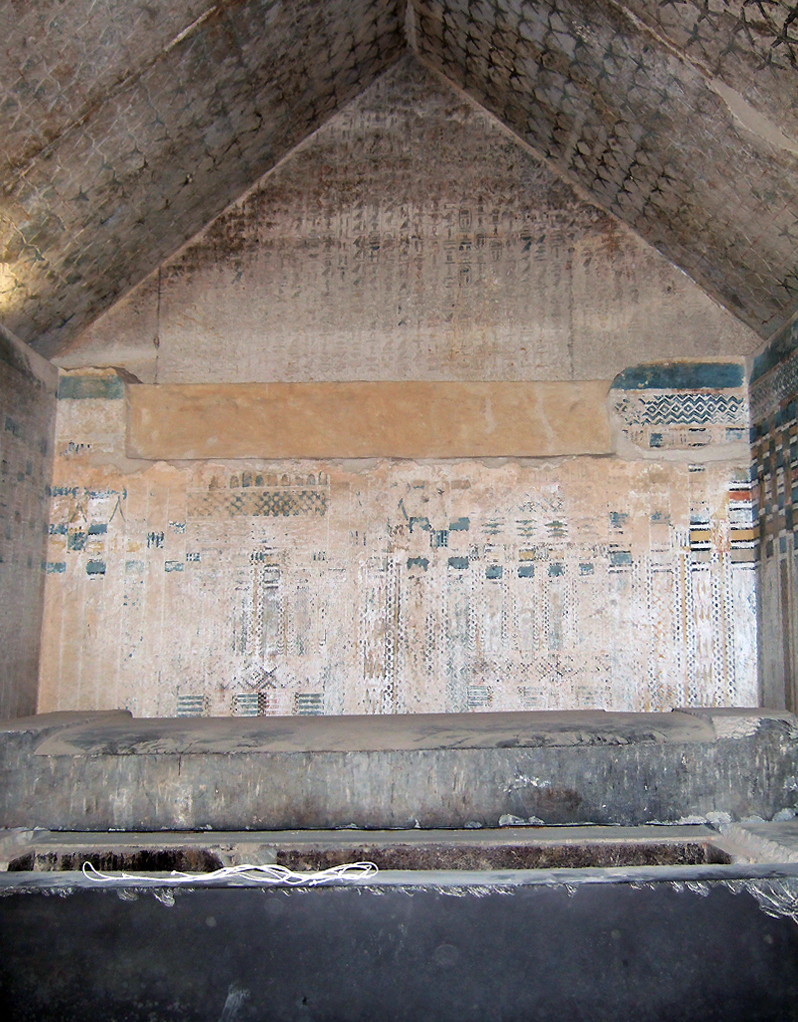

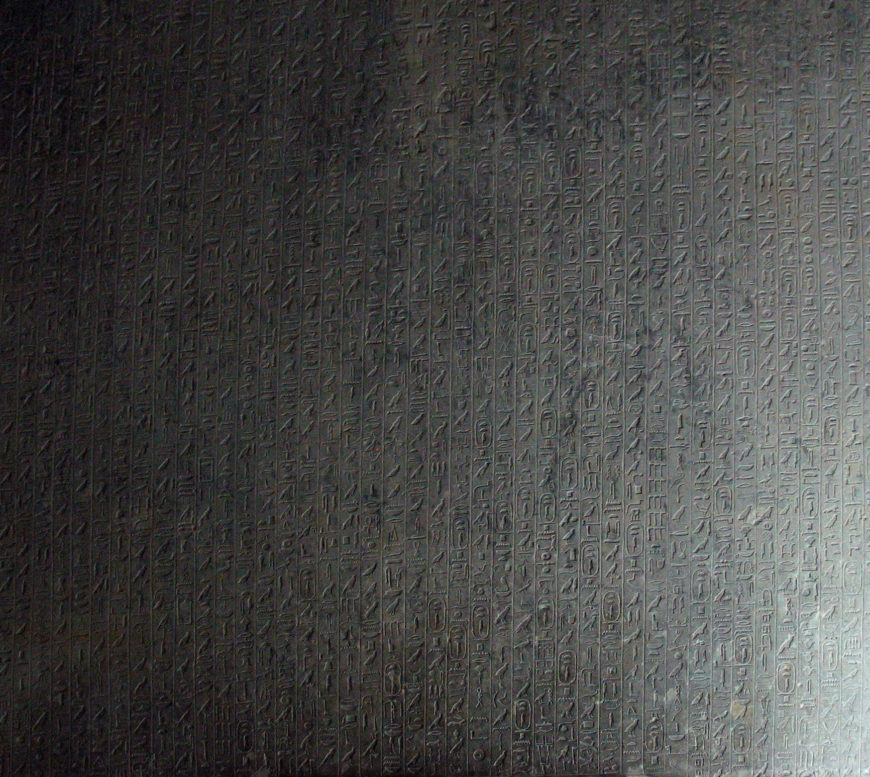

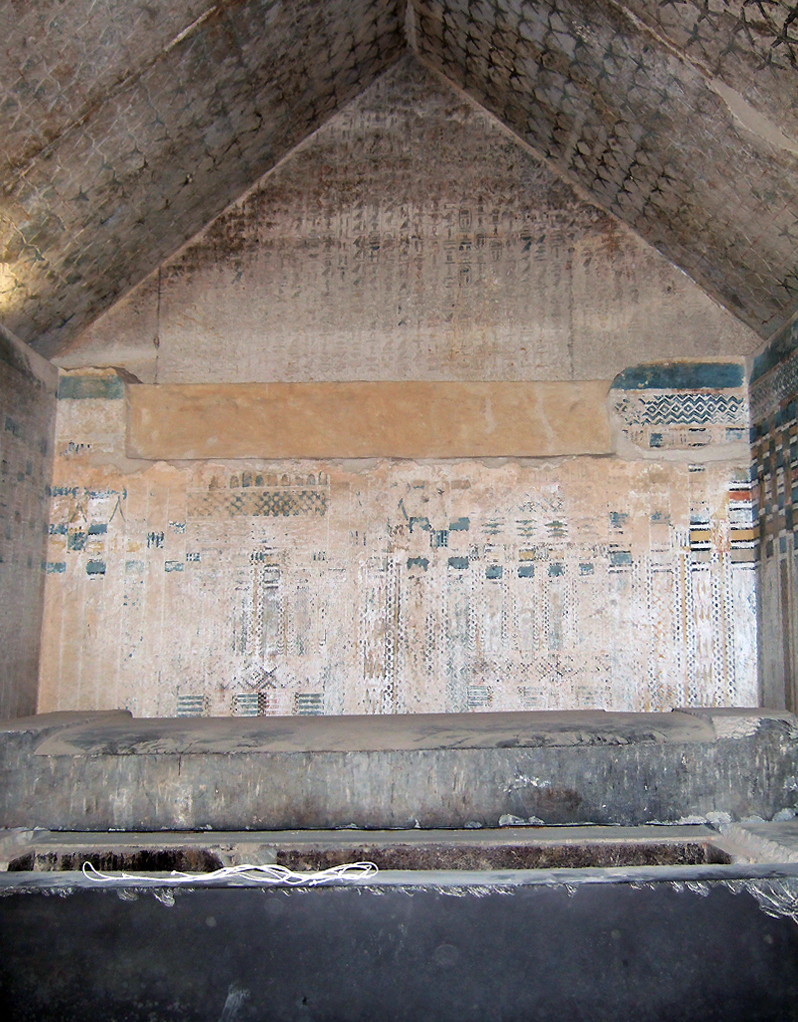

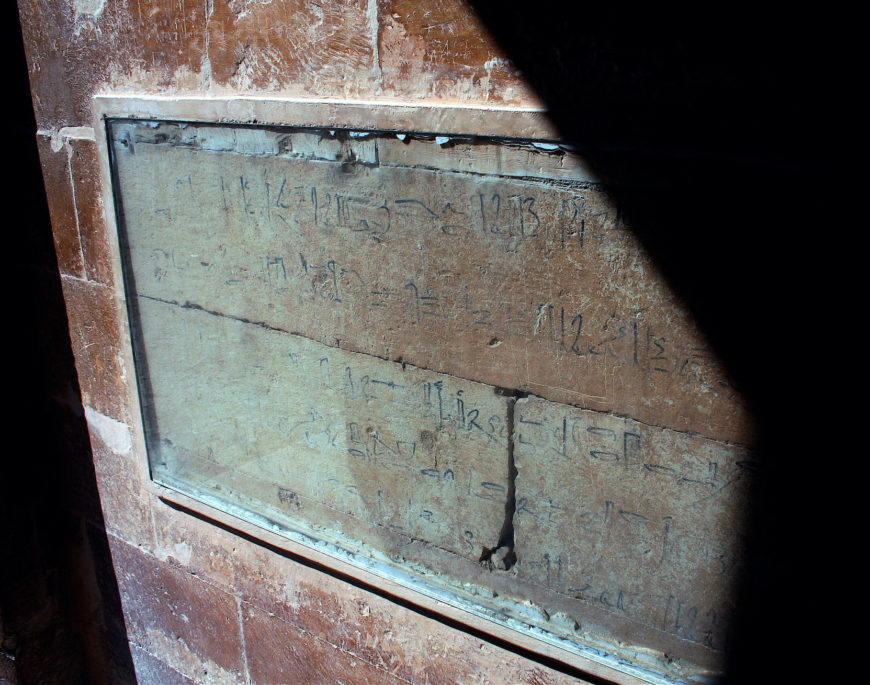

Detail of Pyramid Text inscribed on the wall of a subterranean room in Teti’s pyramid, at Saqqara, Dynasty 6, Teti’s reign c. 2345–2323 B.C.E. (photo: Chipdawes)

Pyramid Text inscribed on the wall of a subterranean room in Teti’s pyramid, at Saqqara (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom

The massive pyramids at Giza included no inscriptions, but beginning with King Unas of the Fifth Dynasty (c 2375–2345 B.C.E.), the walls of the royal burial chamber were covered with vertical columns of text written in monumental hieroglyphs and often outlined in blue-green (a color of regeneration).

These Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom were initially preserved only inscribed on the walls of the burial chambers of royal pyramid tombs. Over time these became more available for display in private tombs and began appearing on objects in the tombs of elite individuals. From the surviving evidence, however, it is clear that there was a common collection of mortuary rites—equally valid for king and commoner—that were being used by both groups as early as the Fourth Dynasty.

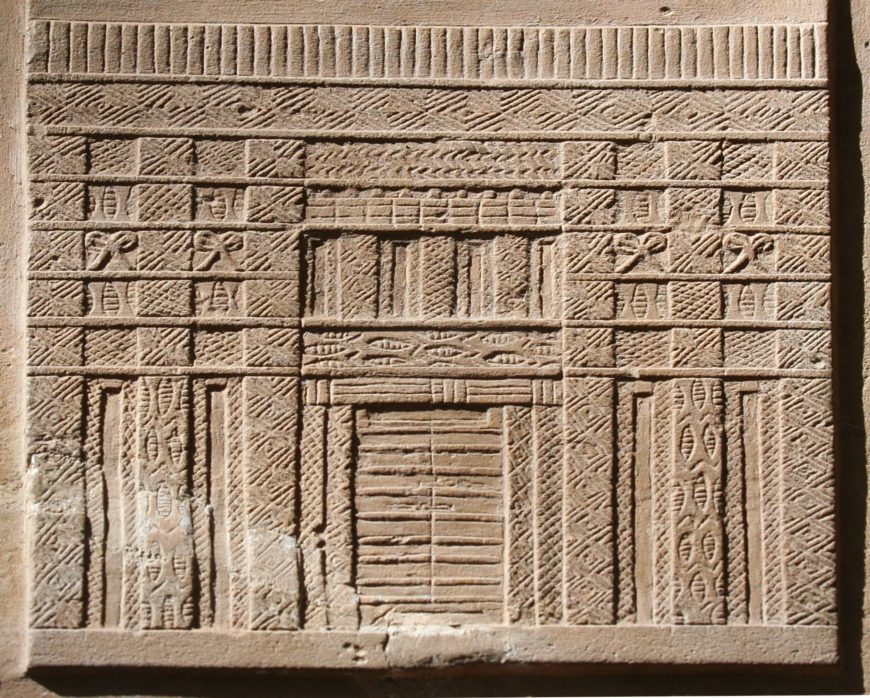

Unas’ burial chamber displaying the sarcophagus, royal palace facade motif, west gable inscriptions, and starry ceiling, Dynasty 5 (Unas, c. 2375–2345 B.C.E.) (photo: Vincent Brown, CC BY 2.0)

These are among the earliest religious writings from anywhere in the world. The text was written in sections, each beginning with the phrase “words to be spoken.” They are often referred to by modern scholars as “spells” but are in fact religious texts. The texts probably derived from a variety of sources, like hymns, lists of divine epithets, daily life magical spells, and phrases that accompanied ritual actions. This collection of texts had clearly been in use for quite some time for both royal and non-royal burials before they were inscribed on the walls of Unas’s burial chamber and antechamber. Their goal was to aid the deceased in avoiding decay and to help their spirit ascend to the celestial realm, taking their place among the gods as one of the “imperishable stars.”

The Pyramid Texts present a mix of spell types—some were written in first person, meant to be spoken by the spirit of the deceased, while others were in second person, intended to be spoken by a lector priest or heir as part of the funerary rituals. These spells likely were recited as part of the funerary rites. The mortuary rituals probably began in the memorial temple or chapel and moved inward toward the burial chamber with the interment; there is often a locational element to spell placement, like the protective spells that are inscribed near the entrance and offering spells inscribed on the north walls of the burial chambers while the “Morning” ritual appears on the east wall. The offering rituals included texts related to presenting offerings, libations, and incense to the deceased and the performance of the Opening of the Mouth ritual.