Introduction to Early Medieval Art and Architecture

Introduction to the Early Medieval Period

The dark ages?

So much of what the average person knows, or thinks they know, about the Middle Ages comes from film and tv. When I polled a group of well-educated friends on Facebook, they told me that the word “medieval” called to mind Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Blackadder, The Sword in the Stone, lusty wenches, feasting, courtly love, the plague, jousting and chain mail.

Perhaps someone who had seen (or better yet read) The Name of the Rose or Pillars of the Earth would add cathedrals, manuscripts, monasteries, feudalism, monks and friars.

Petrarch, an Italian poet and scholar of the fourteenth century, famously referred to the period of time between the fall of the Roman Empire (c. 476) and his own day (c. 1330s) as the Dark Ages. Petrarch believed that the Dark Ages was a period of intellectual darkness due to the loss of the classical learning, which he saw as light. Later historians picked up on this idea and ultimately the term Dark Ages was transformed into Middle Ages. Broadly speaking, the Middle Ages is the period of time in Europe between the end of antiquity in the fifth century and the Renaissance, or rebirth of classical learning, in the fifteenth century and sixteenth centuries.

Not so dark after all

Characterizing the Middle Ages as a period of darkness falling between two greater, more intellectually significant periods in history is misleading. The Middle Ages was not a time of ignorance and backwardness, but rather a period during which Christianity flourished in Europe. Christianity, and specifically Catholicism in the Latin West, brought with it new views of life and the world that rejected the traditions and learning of the ancient world.

During this time, the Roman Empire slowly fragmented into many smaller political entities. The geographical boundaries for European countries today were established during the Middle Ages. This was a period that heralded the formation and rise of universities, the establishment of the rule of law, numerous periods of ecclesiastical reform and the birth of the tourism industry. Many works of medieval literature, such as the Canterbury Tales, the Divine Comedy, and The Song of Roland, are widely read and studied today.

The visual arts prospered during Middles Ages, which created its own aesthetic values. The wealthiest and most influential members of society commissioned cathedrals, churches, sculpture, painting, textiles, manuscripts, jewelry and ritual items from artists. Many of these commissions were religious in nature but medieval artists also produced secular art. Few names of artists survive and fewer documents record their business dealings, but they left behind an impressive legacy of art and culture.

Byzantium

When I polled the same group of friends about the word “Byzantine,” many struggled to come up with answers. Among the better ones were the song “Istanbul (Not Constantinople)” sung by They Might Be Giants, crusades, things that are too complex (like the tax code or medical billing), Hagia Sophia, the poet Yeats, mosaics, monks, and icons. Unlike Western Europe in the Middle Ages, the Byzantine Empire is not romanticized in television and film.

Approximate boundaries of the Byzantine Empire, mid-6th century (underlying map © Google)

In the medieval West, the Roman Empire fragmented, but in the Byzantine East, it remained a strong, centrally-focused political entity. Byzantine emperors ruled from Constantinople, which they thought of as the New Rome. Constantinople housed Hagia Sophia, one of the world’s largest churches, and was a major center of artistic production.

Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, 532–37 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Byzantine Empire experienced two periods of Iconoclasm (730–787 and 814–842), when images and image-making were problematic. Iconoclasm left a visible legacy on Byzantine art because it created limits on what artists could represent and how those subjects could be represented. Byzantine Art is broken into three periods. Early Byzantine or Early Christian art begins with the earliest extant Christian works of art c. 250 and ends with the end of Iconoclasm in 842. Middle Byzantine art picks up at the end of Iconoclasm and extends to the sack of Constantinople by Latin Crusaders in 1204. Late Byzantine art was made between the sack of Constantinople and the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

In the European West, Medieval art is often broken into smaller periods. These date ranges vary by location.

Cite this page as: Dr. Nancy Ross, “Introduction to the Middle Ages,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-the-middle-ages/.

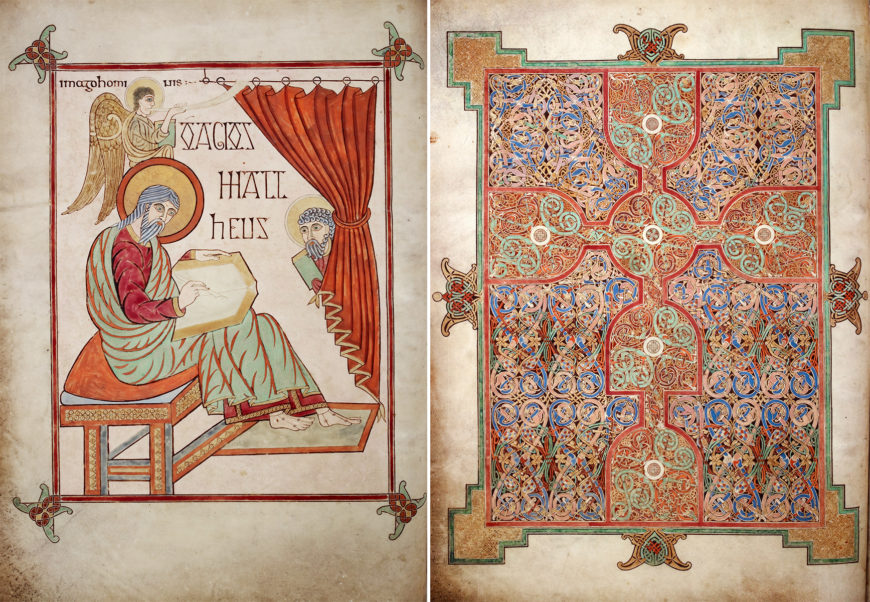

A new pictorial language: the image in early medieval art

Praxiteles, Cnidian Aphrodite, 4th century – marble copy known as the “Capitoline Venus,” marble, 193 cm high (Capitoline Museum, Rome), photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA

An illusion of reality

Classical art, or the art of ancient Greece and Rome, sought to create a convincing illusion for the viewer. Artists sculpting the images of gods and goddesses tried to make their statues appear like an idealized human figure. Some of these sculptures, such as the Aphrodite of Knidos by Praxiteles, were so lifelike that legends spread about the statues coming to life and speaking to people. After all, a statue of a god or goddess in the ancient world was believed to embody deity.

The problem for early Christians

The illusionary quality of classical art posed a significant problem for early Christian theologians. When God dictated the ten commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai, God expressly forbade the Israelites from making any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth (Exodus 20:4). Early Christians saw themselves as the spiritual progeny of the Israelites and tried to comply with this commandment. Nevertheless, many early Christians were converted pagans who were accustomed to images in religious worship. The use of images in religious ritual was visually compelling and difficult to abandon.

Tertullian asks: Can artists be Christians?

Tertullian, an influential early Christian author living in the second and third centuries, wrote a treatise titled On Idolatry in which he asks if artists could, in fact, be Christians. In this text, he argues that all illusionary art, or all art that seeks to look like something or someone in nature, has the potential to be worshiped as an idol. Arguing fervently against artists as Christians, he acknowledges that there are many artists who are Christians and indeed some who are even priests. In the end, Tertullian asks artists to quit their work and become craftsmen.

Augustine: Illusionary images are lies

Another influential early Christian writer, St. Augustine of Hippo, was also concerned about images, but for different reasons. In his Soliloquies (386-87), Augustine observes that illusionary images, like actors, are lying. An actor on a stage lies because he is playing a part, trying to convince you that he is a character in the script when in truth he is not. An image lies because it is not the thing it claims to be. A painting of a cat is not a cat, but the artist tries to convince the viewer that it is. Augustine cannot reconcile these lies with patterns of divine truth and therefore does not see a place for images in Christian practice.*

Fortunately for art and history, not everyone agreed with Tertullian and Augustine and the use of images persisted. Nevertheless their style and appearance changed in order to be more compatible with theology.

Mosaic in the apse of the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, 6th century (Ravenna, Italy), , photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA

Towards abstraction (and away from illusion)

Christian art, which was initially influenced by the illusionary quality of classical art, started to move away from naturalistic representation and instead pushed toward abstraction. Artists began to abandon classical artistic conventions like shading, modeling and perspective conventions that make the image appear more real. They no longer observed details in nature to record them in paint, bronze, marble, or mosaic.

Instead, artists favored flat representations of people, animals and objects that only looked nominally like their subjects in real life. Artists were no longer creating the lies that Augustine warned against, as these abstracted images removed at least some of the temptations for idolatry. This new style, adopted over several generations, created a comfortable distance between the new Christian empire and its pagan past.

In Western Europe, this approach to the visual arts dominated until the imperial rule of Charlemagne (800-814) and the accompanying Carolingian Renaissance. This controversy over the legitimacy and orthodoxy of images continued and intensified in the Byzantine Empire. The issue was eventually resolved, in favor of images, during the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.

*There is some irony here since Augustine’s position echos, to some extent, the writing of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. In book X of The Republic (c. 360 B.C.E.), Plato describes a true thing as having been made by God, while in the earthly sphere, a carpenter, for example, can only build a replica of this truth (Plato uses a bed to illustrate his point). Plato states that a painter who renders the carpenter’s bed creates an illusion that is two steps from the truth of God.

Cite this page as: Dr. Nancy Ross, “A new pictorial language: the image in early medieval art,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/a-new-pictorial-language-the-image-in-early-medieval-art/.

Medieval Churches: Sources and Forms

Exterior view of the apse, Basilica of Santa Sabina, c. 432 C.E., Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA)

Many of Europe’s medieval cathedrals are museums in their own right, housing fantastic examples of craftsmanship and works of art. Additionally, the buildings themselves are impressive. Although architectural styles varied from place to place, building to building, there are some basic features that were fairly universal in monumental churches built in the Middle Ages, and the prototype for that type of building was the Roman basilica.

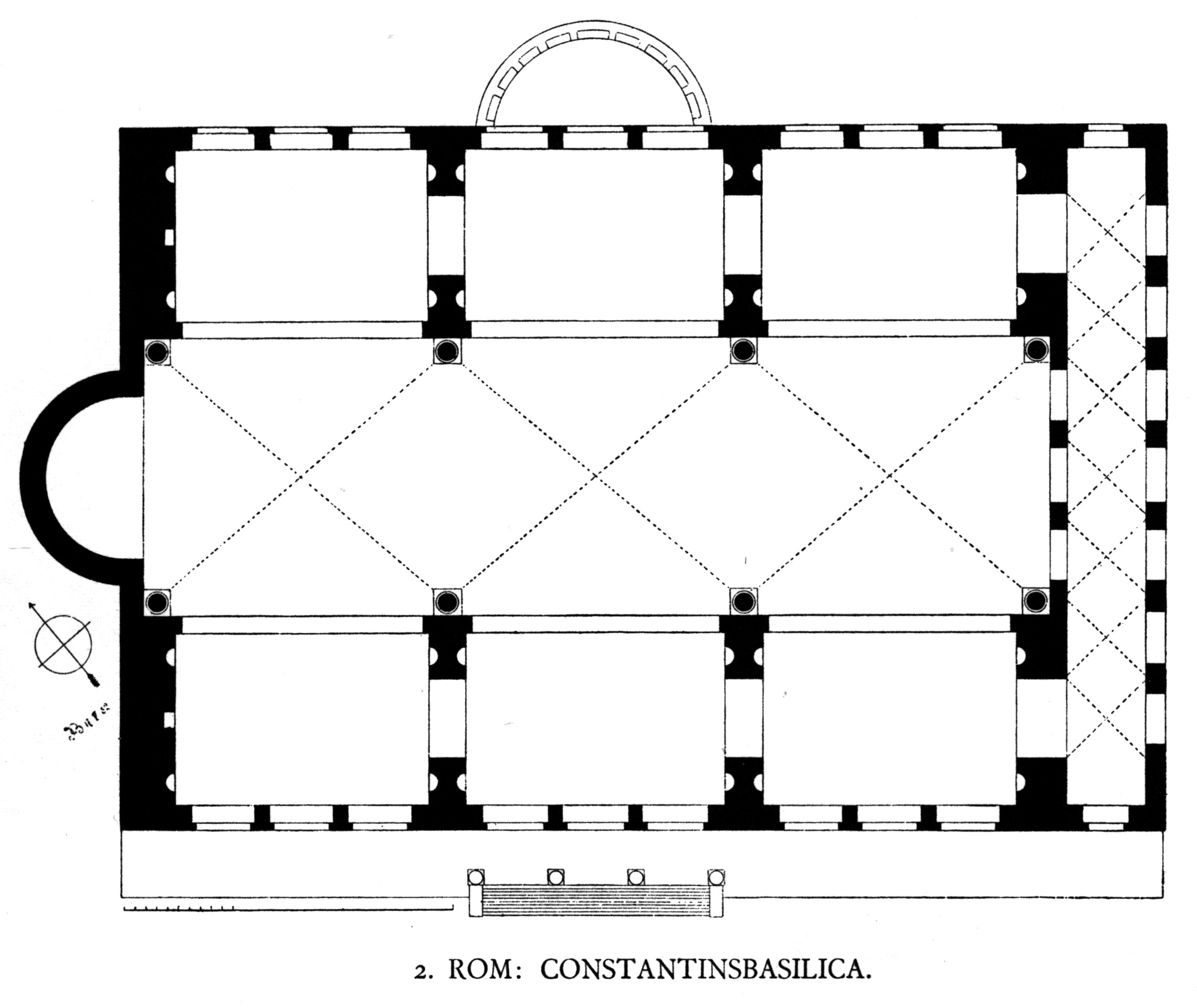

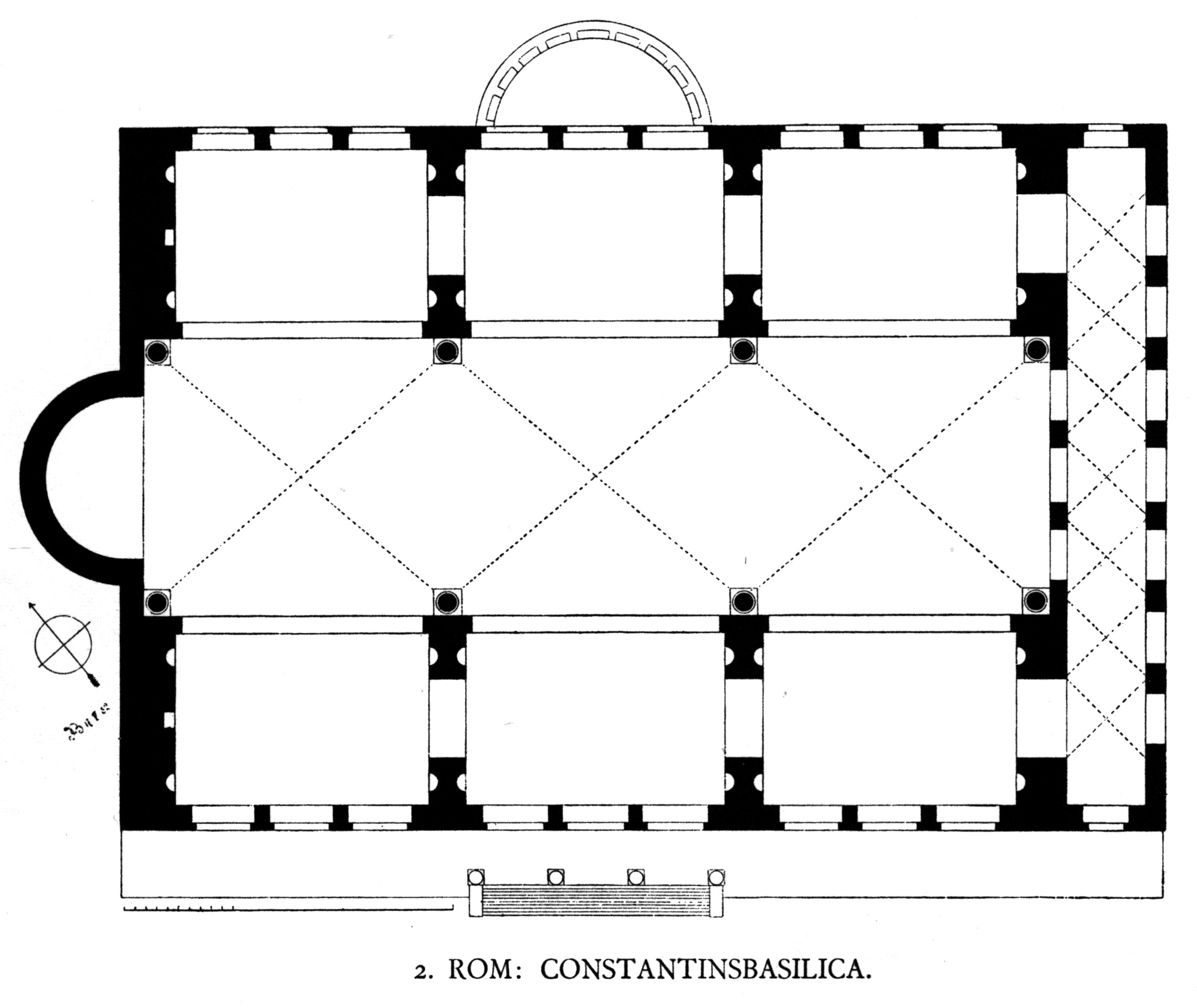

Floor plan of the Roman Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine, 308–312 C.E. (photo: Fb78)

Prototype: The ancient Roman basilica

In ancient Rome, the basilica was created as a place for tribunals and other types of business. The building was rectangular in shape, with the long, central portion of the hall made up of the nave. Here the interior reached its fullest height. The nave was flanked on either side by a colonnade (a row of columns) that delineated the side aisles, which were of a lower height than the nave. Because these side aisles were lower, the roof over this section was below the roofline of the nave, allowing for windows near the ceiling of the nave. This band of windows was called the clerestory. At the far end of the nave, away from the main door, was a semi-circular extension, usually with a half-dome roof. This area was the apse, and is where the magistrate or other senior officials would hold court.

Because this plan allowed for many people to circulate within a large, and awesome, space, the general plan became an obvious choice for early Christian buildings. The religious rituals, masses, and pilgrimages that became commonplace by the Middle Ages were very different from today’s services, and to understand the architecture it is necessary to understand how the buildings were used and the components that made up these massive edifices.

View down the nave towards the apse—the row of windows above the nave arcade is called the clerestory, and there is an aisle on either side of the nave. Basilica of Santa Sabina, c. 432 C.E., Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

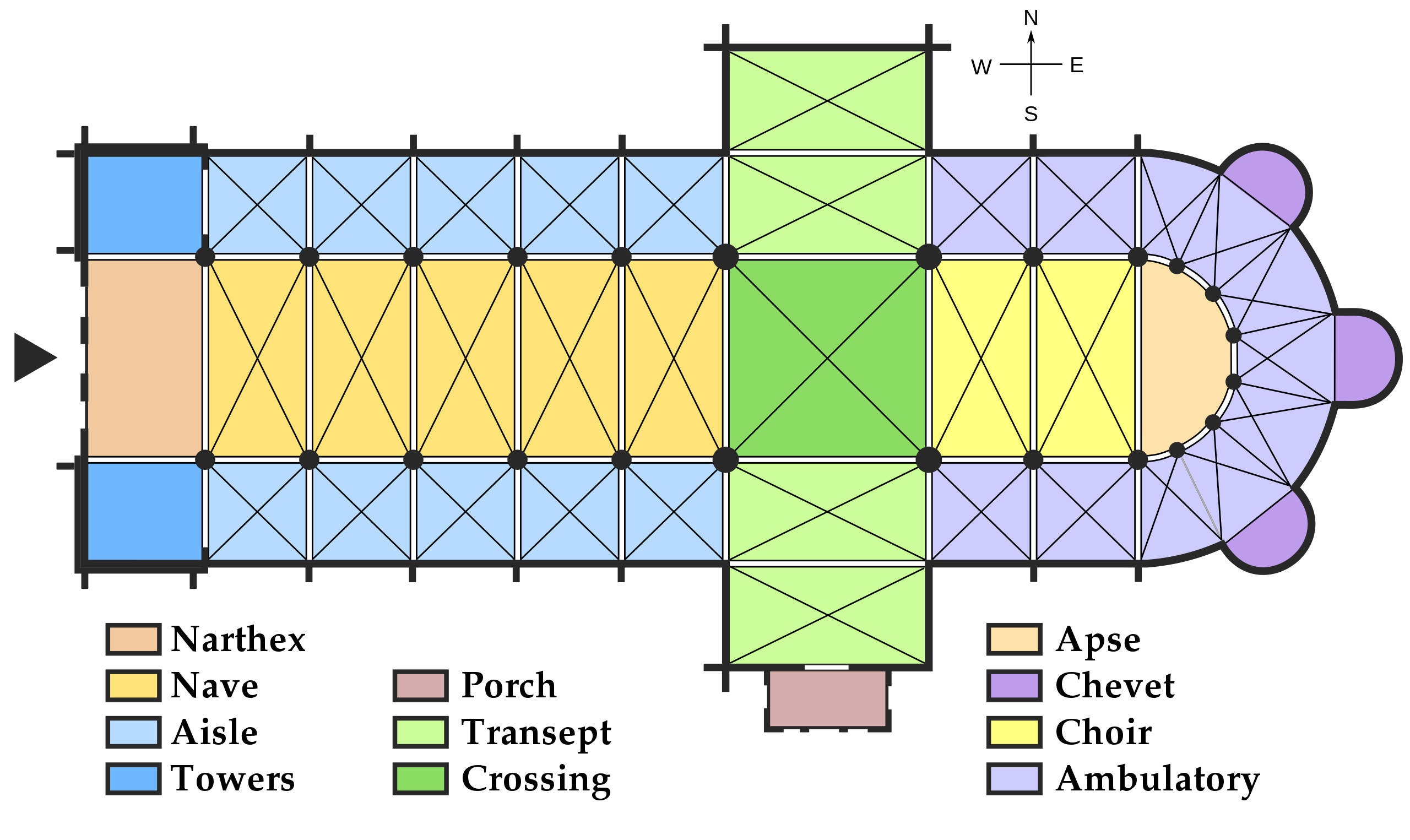

The church plan

Although medieval churches are usually oriented with the altar on the east end, they all vary slightly. When a new church was to be built, the patron saint was selected and the altar location laid out. On the saint’s day (the day on which a saint is particularly commemorated), a line would be surveyed from the position of the rising sun through the altar site and extending in a westerly direction. This was the orientation of the new building.

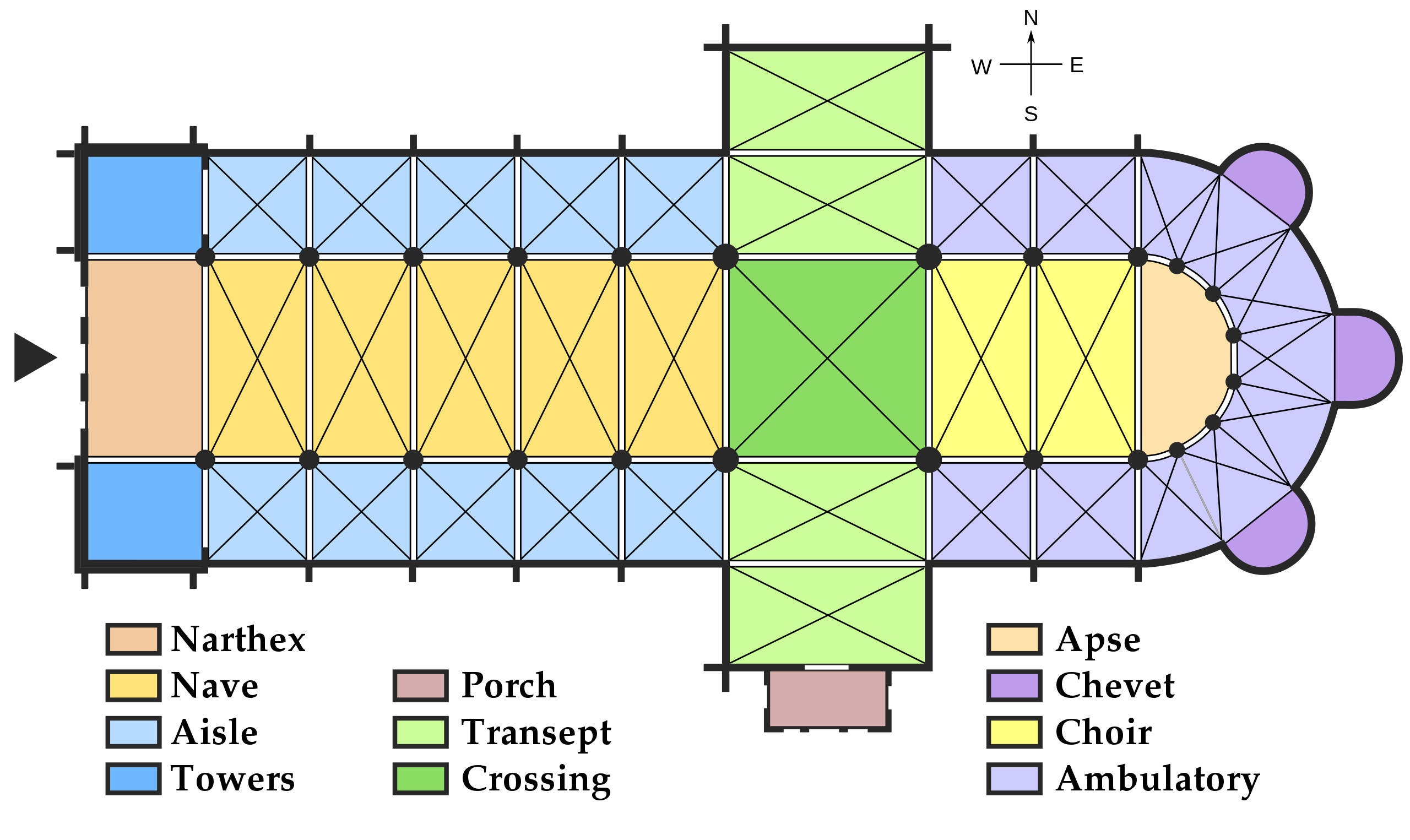

Medieval church floor plan (diagram: Justinbb, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The entrance foyer at the west end is called the narthex, but this is not found in all medieval churches. Daily access may be through a door on the north or south side. The largest, central, western door may have been reserved for ceremonial purposes.

Inside, you should imagine the interior space without the chairs or pews that we are used to seeing today. In very extensive buildings there may be two side aisles, with the ceiling of the outer one lower than the one next to the nave. This hierarchy of size and proportion extended to the major units of the plan—the bays. The vault is the arched roof or ceiling, or a section of it.

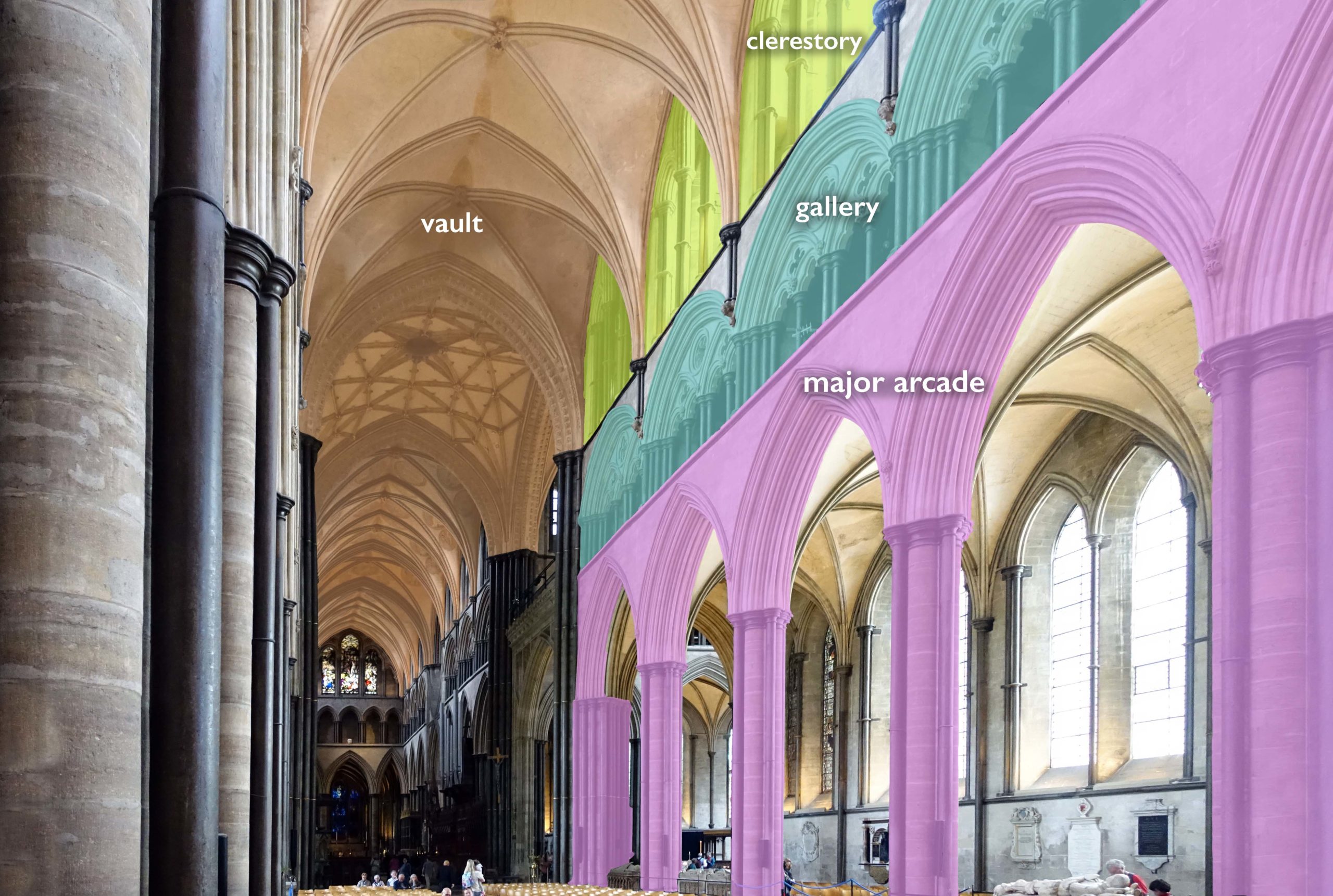

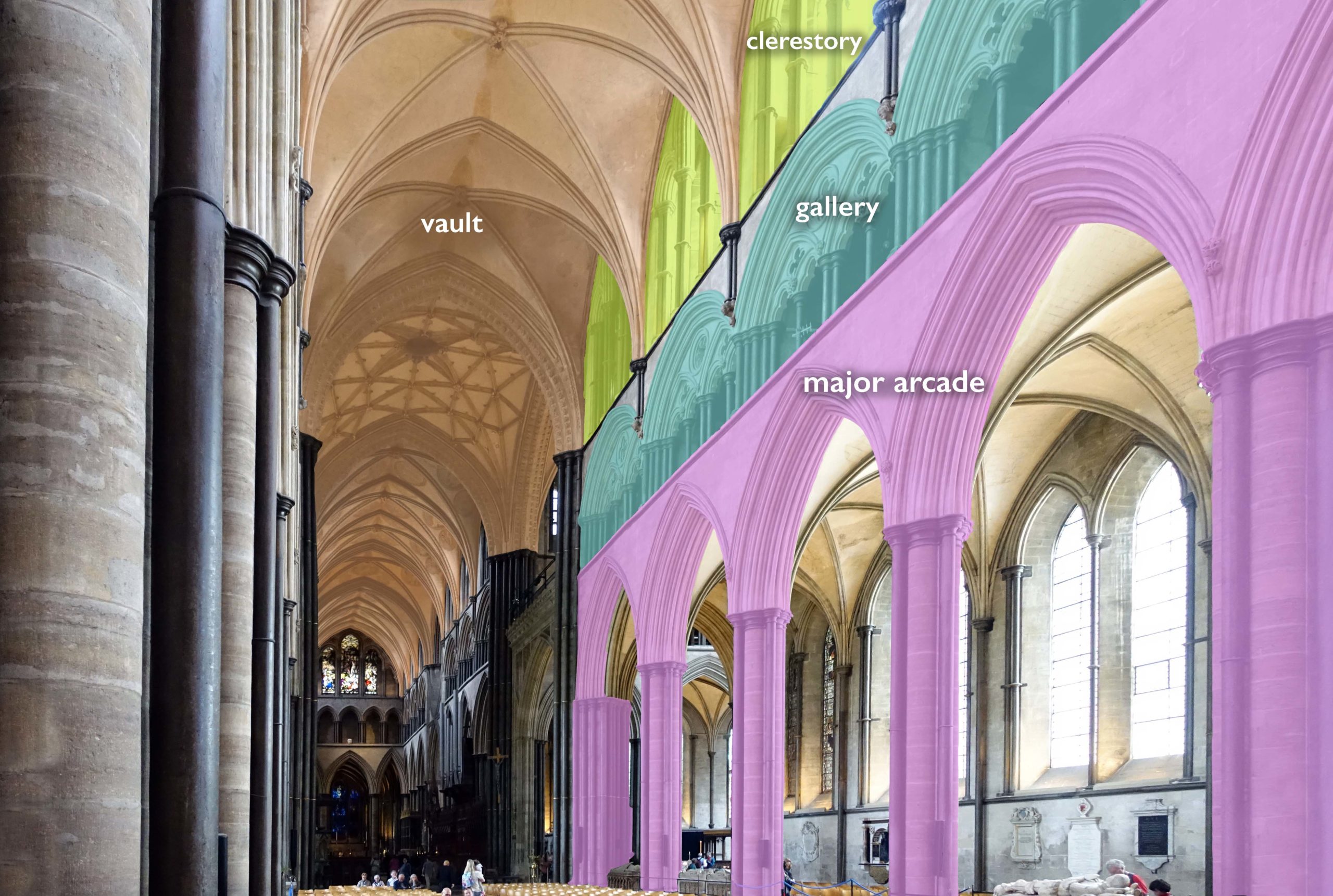

Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Major arcade, gallery, clerestory, and vault, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury England, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

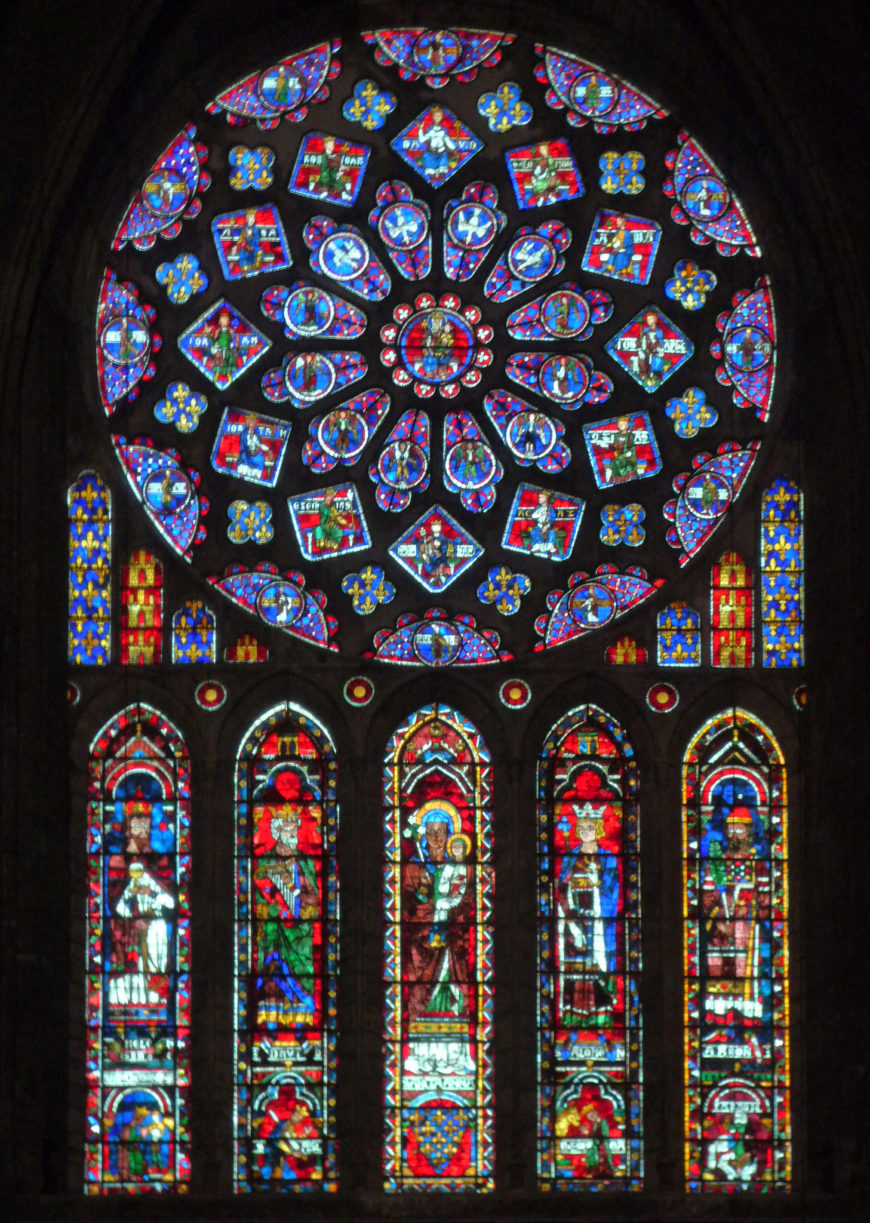

The major arcade (row of arches) at the ground floor level is topped by a second arcade, called the gallery, which is topped by the clerestory (the windows). In later Gothic churches, we sometimes see yet another level below the clerestory, called the triforium.

The nave was used for the procession of the clergy (priests) to the altar. The main altar was basically in the position of the apse in the ancient Roman basilica, although in some designs it is further forward. The area around the altar—the choir or chancel—was reserved for the clergy or monks, who performed services throughout the day.

The cathedrals and former monastery churches are much larger than needed for the local population. They expected and received numerous pilgrims who came to various shrines and altars within the church where they might pray to a supposed piece of the true cross, or a bone of a martyr, or the tomb of a king. The pilgrims entered the church and found their way to the chapel or altar of their desire—therefore, the side aisles made an efficient path for pilgrims to come and go without disrupting the daily services.

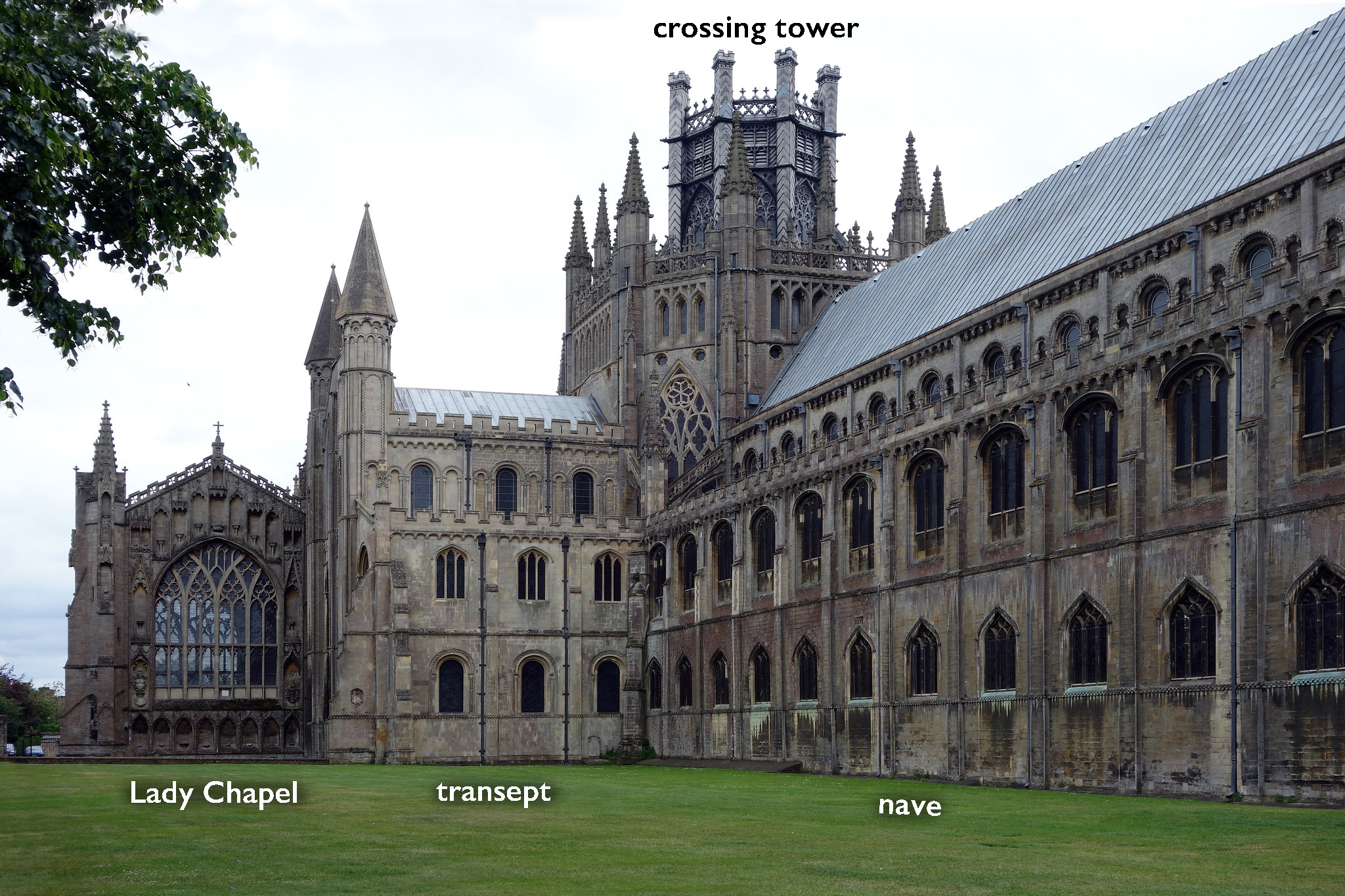

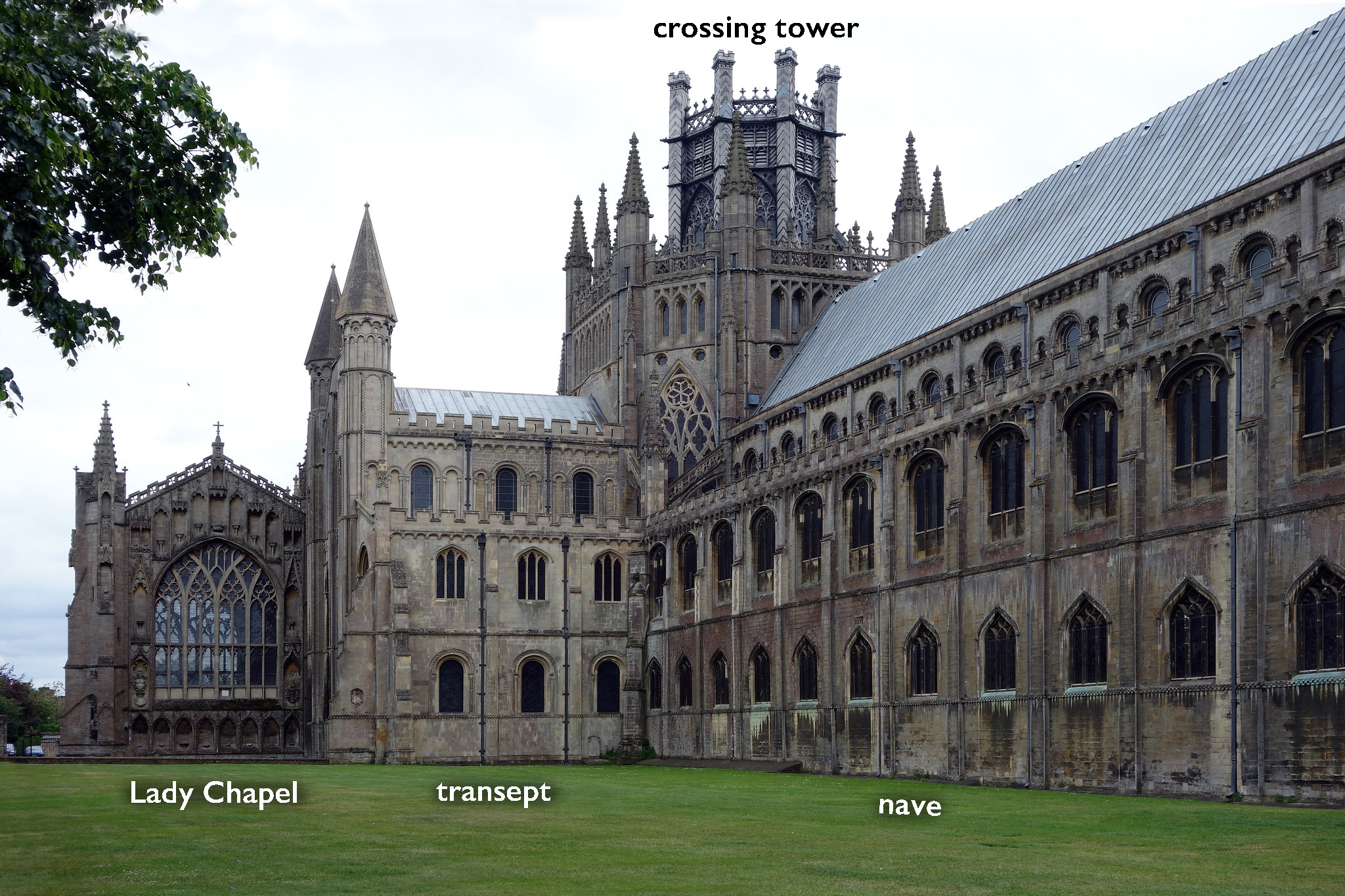

View of the Lady Chapel, northeast transept, nave, and the Octagon (crossing tower), Ely Cathedral, Cambridgeshire, England, founded by Princess Æthelthryth (also Etheldreda) in 672 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Development of this plan over time shows that very soon the apse was elongated, adding more room to the choir. Additionally, the ends of the aisles developed into small wings themselves, known as transepts. These were also extended, providing room for more tombs, more shrines, and more pilgrims.

The area where the axes of the nave and transepts meet is called, logically, the crossing.

View of the apse with glimpses of the ambulatory and radiating chapels beyond behind the gate, Robert de Luzarches, Thomas de Cormont, and Renaud de Cormont, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220, Amiens, France (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An aisle often surrounds the apse, running behind the altar. Called the ambulatory, this aisle accessed additional small chapels, called radiating chapels or chevets. Of course, there are many variations on these typical building blocks of medieval church design. Different regions had different tastes, greater or lesser financial power, more or less experienced architects and masons, which created the diversity of medieval buildings still standing today.

Cite this page as: Valerie Spanswick, “Medieval churches: sources and forms,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/medieval-churches-sources-and-forms/.