Etruscan civilization, 750–500 B.C.E., based on a map from The National Geographic Magazine, vol.173 no.6 (June 1988) (photo: Ras67, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Before the small village of Rome became “Rome” with a capital R (to paraphrase the author D. H. Lawrence), a brilliant civilization once controlled almost the entire peninsula we now call Italy. This was the Etruscan civilization, a vanished culture whose achievements set the stage not only for the development of ancient Roman art and culture but for the Italian Renaissance as well.

Though you may not have heard of them, the Etruscans were the first “superpower” of the Western Mediterranean who, alongside the Greeks, developed the earliest true cities in Europe. They were so successful, in fact, that the most important cities in modern Tuscany (Florence, Pisa, and Siena, to name a few) were first established by the Etruscans and have been continuously inhabited since then.

Yet the labels “mysterious” or “enigmatic” are often attached to the Etruscans since none of their own histories or literature survives. This is particularly ironic as it was the Etruscans who were responsible for teaching the Romans the alphabet and for spreading literacy throughout the Italian peninsula.

The influence on ancient Rome

Etruscan influence on ancient Roman culture was profound. It was from the Etruscans that the Romans inherited many of their own cultural and artistic traditions, from the spectacle of gladiatorial combat, to hydraulic engineering, temple design, and religious ritual, among many other things. In fact, hundreds of years after the Etruscans had been conquered by the Romans and absorbed into their empire, the Romans still maintained an Etruscan priesthood in Rome (which they thought necessary to consult when under attack from invading “barbarians”).

We even derive our very common word “person’” from the Etruscan mythological figure Phersu—the frightful, masked figure you see in this Early Etruscan tomb painting who would engage his victims in a dreadful “game” of blood letting in order to appease the soul of the deceased (the original gladiatorial games, according to the Romans!).

Etruscan art and the afterlife

Early on the Etruscans developed a vibrant artistic and architectural culture, one that was often in dialogue with other Mediterranean civilizations. Trading of the many natural mineral resources found in Tuscany, the center of ancient Etruria, caused them to bump up against Greeks, Phoenicians, and Egyptians in the Mediterranean. With these other Mediterranean cultures, they exchanged goods, ideas, and, often, a shared artistic vocabulary.

Terracotta kantharos (vase), 7th century B.C.E., Etruscan, terracotta, 18.39 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Unlike the Greeks, however, the majority of our knowledge about Etruscan art comes largely from their burials. (Since most Etruscan cities are still inhabited, they hide their Etruscan art and architecture under Roman, Medieval, and Renaissance layers.) Fortunately, though, the Etruscans cared very much about equipping their dead with everything necessary for the afterlife—from lively tomb paintings to sculpture to pottery that they could use in the next world.

From their extensive cemeteries, we can look at the “world of the dead” and begin to understand some about the “world of the living.” During the early phases of the Etruscan civilization, they conceived of the afterlife in terms of life as they knew it. When someone died, he or she would be cremated and provided with another “home” for the afterlife.

Hut urn, Etruscan, 8th century B.C.E., ceramics, 22 x 23 x 28 cm (The Walters Art Museum)

This type of hut urn, made of an unrefined clay known as impasto, would be used to house the cremated remains of the deceased. Not coincidentally, it shows us in miniature form what a typical Etruscan house would have looked like in Iron Age Etruria—oval with a timber roof and a smoke hole for an internal hearth.

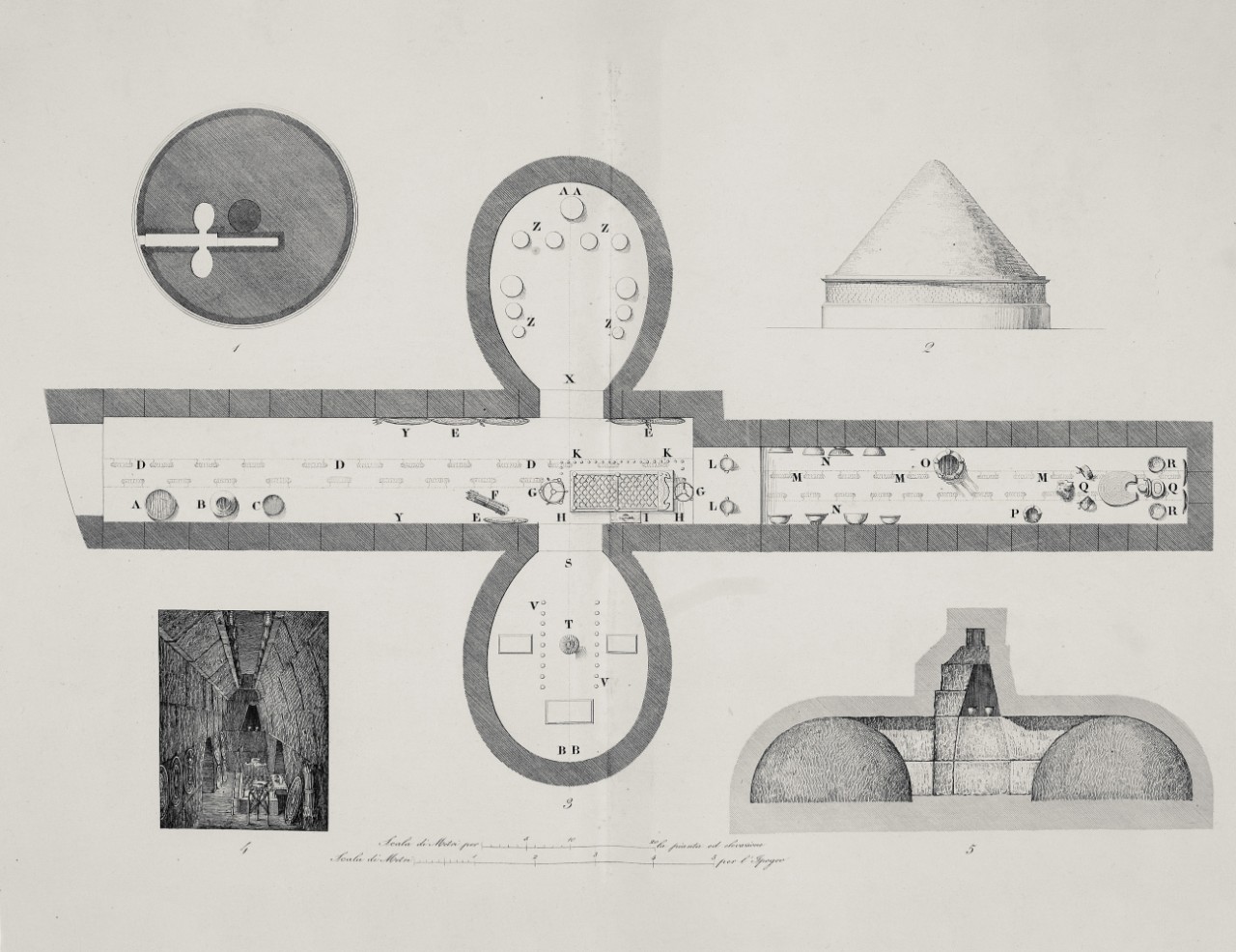

Regolini-Galassi Tomb plan (image: Vatican Museums)

More opulent tombs

Later on, houses for the dead became much more elaborate. During the Orientalizing period, when the Etruscans began to trade their natural resources with other Mediterranean cultures and became staggeringly wealthy as a result, their tombs became more and more opulent.

The well-known Regolini-Galassi tomb from the city of Cerveteri shows how this new wealth transformed the modest hut to an extravagant house for the dead. Built for a woman clearly of high rank, the massive stone tomb contains a long corridor with lateral, oval rooms leading to a main chamber.

Five lions (detail), Large Parade Fibula, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, from the main tomb in the lower chamber, 675-650 B.C., gold: embossed, punched, cut and granulated (Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A stroll through the Etruscan rooms in the Vatican Museum where the tomb artifacts are now housed presents a mind-boggling view of the enormous wealth of the period. Found near the woman were objects of various precious materials intended for personal adornment in the afterlife—a gold pectoral, gold bracelets, a gold brooch (or fibula) of outsized proportions, among other objects—as well as silver and bronze vessels, and numerous other grave goods and furniture.

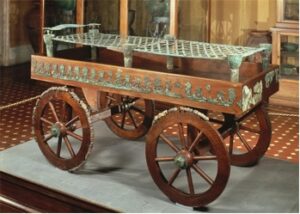

Of course, this important woman might also need her four-wheeled bronze-sheathed carriage in the afterlife as well as an incense burner, jewelry of amber and ivory, and, touchingly, her bronze bed around which thirty-three figurines, all in various gestures of mourning, were arranged.

Mourners in Bucchero, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, 675–650 B.C.E., Bucchero, 9.5–10.8 x 2.7–3.8 cm (Vatican Museums)

Though later periods in Etruscan history are not characterized by such wealth, the Etruscans were, nevertheless, extremely powerful and influential and left a lasting imprint on the city of Rome and other parts of Italy.