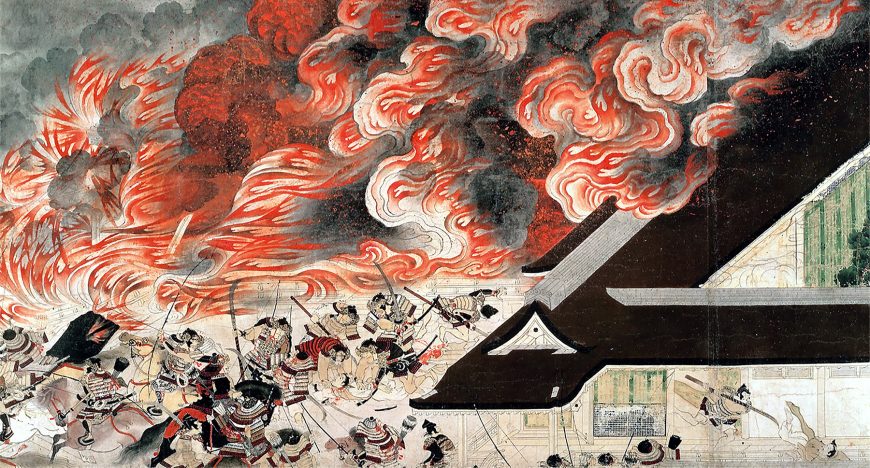

Burning Palace (detail), Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

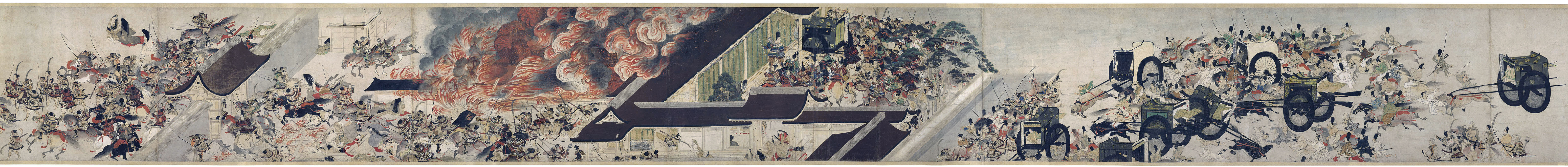

Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace fully unrolled (right side above, left side below), Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

It is hard to imagine an image of war that matches the visceral and psychological power of the Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace. This thirteenth-century portrayal of a notorious incident from a century earlier appears on a handscroll, a common East Asian painting format in Japan called an emaki. It also is a prime example of the action-packed otoko-e, “men’s paintings,” created in the Kamakura period.

Designed to be unrolled in sections for close-up viewing, it shows the basic features of this pictorial form: a bird’s eye view of action moves right-to-left (between a written introduction and conclusion). In vibrant outline and washes of color, the story (one event in an insurrection—more on this below) unfolds sequentially, so the main characters appear multiple times.

The attention to detail is so exact that historians consider it a uniquely valuable reference for this period: from the royal mansion’s walled gateways, unpainted wooden buildings linked by corridors, bark roofs, large shutters and bamboo blinds that open to verandas, to the scores of foot soldiers, cavalry, courtiers, priests, imperial police, and even the occasional lady—each individualized by gesture and facial expression (from horror to morbid humor), robes, armor, and weaponry which is all easily identifiable according to rank, design, and type.

Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace without framing text, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Unfurled this work stands apart. Its now-forgotten artist used the expressive potential of the long, narrow emaki format with such interpretive brilliance that he perhaps considered that on occasion it might be fully open. He organized a jumble of minutiae into a cohesive narrative arc.

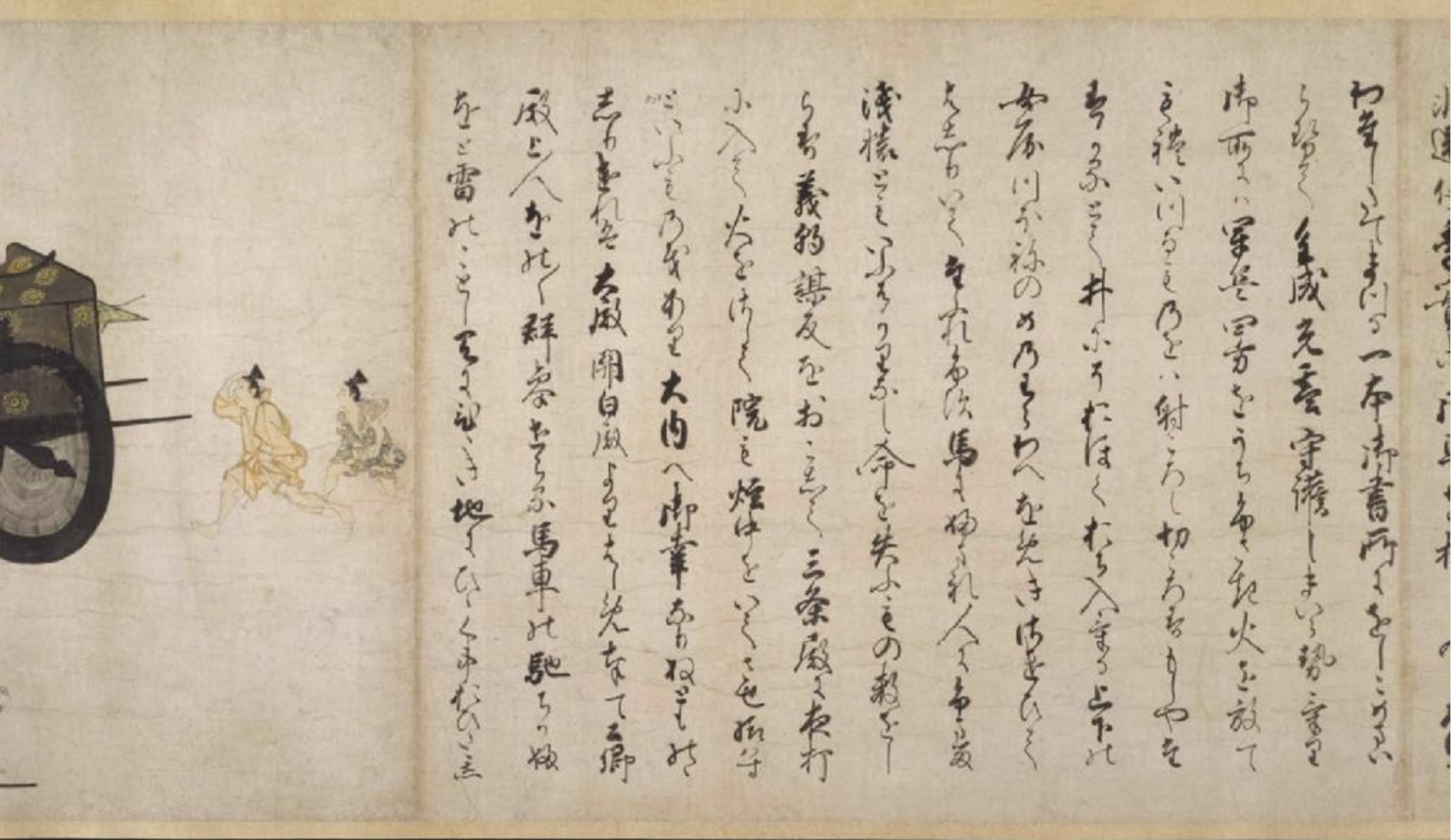

Opening text and ox cart (detail), Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Beginning from a point of ominous calm, a single ox carriage transports the eye to a tangle of shoving and colliding carts and warriors. With escalating violence, the energy pulses, swells, and then rushes to a crescendo of graphic hand-to-hand mayhem—decapitations, stabbings and hacking, the battle’s apex marked at the center by the palace rooflines slashing through the havoc like a bolt of lightening followed by an explosion of billowing flame and women fleeing for their lives amid the din.

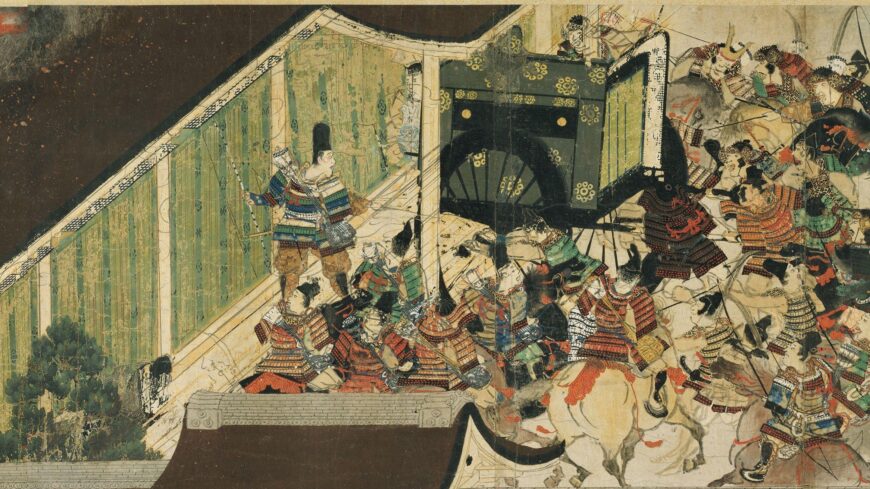

Palace (detail), Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The chaos ebbs as victors and dazed survivors stream through the rear gate, and ends in grisly, surreal calm with the dressed and tagged heads of vanquished nobles on pikes, a disorderly cluster of foot soldiers and cavalry surrounding the ox carriage, their general trotting before them in victorious satisfaction over the smoking wreckage and bloody atrocity left behind.

Closing sequence (detail), Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The Night Attack at Sanjô Palace arrests even the casual viewer with its sheer comprehensibility. Although the artist would likely not have imagined an audience beyond the world he knew, his vision has enthralled viewers across centuries and cultures, making this painting not only among the very finest picture scrolls ever conceived, but also among the most gripping depictions of warfare—creating an irresistible urge to examine the work closely. But in depicting an event that really happened, it comes fully to life only when we know something of what it so vividly portrays.

Aristocrats fleeing (detail), Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

This begins in a brief introduction to a complicated yet fascinating chapter in Japanese history. Incredibly, the appalling incident at Sanjô Palace depicted on the scroll was but one chapter in the vicious Heiji Insurrection of 1159–60. This short war, with two other famous conflicts before and after, punctuated a brutal epoch that came to a close in 1192 with the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate. The stories of these flashpoints of blood thirst, collectively called gunki monogatari, or “war tales,” have inspired a huge body of art over the centuries. The Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, once part of a larger set that pictorialized the entire Heiji incident, survives with two other scrolls, one of them only in remnants.

First half of the handscroll, Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Stories of romanticized martial derring-do, gunki monogatari are history recounted by the victors. They celebrate Japan’s change from a realm controlled by a royal court to one ruled by samurai. But the events originated in the unusual, even unique, nature of Japan’s imperial world. Centered in the city of Kyoto, in some ways it resembled many ancient kingdoms. It was prey to shifting loyalties, betrayals, and factional divisions among ambitious families who would stop at nothing in the quest for power. As elsewhere, emperors had several consorts, and noble daughters served as tools in political marriages to elevate the power of their families, and above all their clan head.

Second half of the handscroll, Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace (detail, left half), Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Unusually, a few patriarchs managed over time to displace imperial authority, relegating emperors to stultifying ceremonial functions. And possibly uniquely, Japanese emperors found a way to reclaim some of that lost power: by abdicating in favor of a successor. Freed from onerous rituals, a “retired” emperor could assert himself. Which prince from which wife of which current or previous emperor would succeed to the throne stood highest among the disputes. By the twelfth century, nobles as well as current and retired emperors had all turned to samurai clans to resolve their bitter rivalries.

Fire (detail), Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The cast of characters in the Night Attack at the Sanjô Palace came from this treacherous world. Sanjô Palace was the home of former Emperor Go-Shirakawa, known for a career as the wiliest and longest‐lived of retired royals. He had recently abdicated in favor of his son Emperor Nijô. The two emperors backed vying sides of the Fujiwara clan, a conspiratorial family unsurpassed in subjugating and sometimes choosing a succession of emperors. One member of this clan, Fujiwara no Nobuyori, plotted against everyone. [1] The Taira and the Minamoto clans served powerful interests in all of these disputes, while also pursuing their own ambitions as bitter rivals of the other.

Dead archer (detail), Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Simply put, the Night Attack was part of Fujiwara no Nobuyori’s bid to seize power by abducting both the emperor (Nijô) and the retired emperor (Go-Shirakawa). Backed by Minamoto no Yoshitomo, head of the Minamoto clan, Nobuyori saw an opportunity when the head of the Taira clan (who supported Emperor Nijō), left Kyoto on a pilgrimage. The emaki depicts the seizing of the retired emperor Go-Shirakawa.

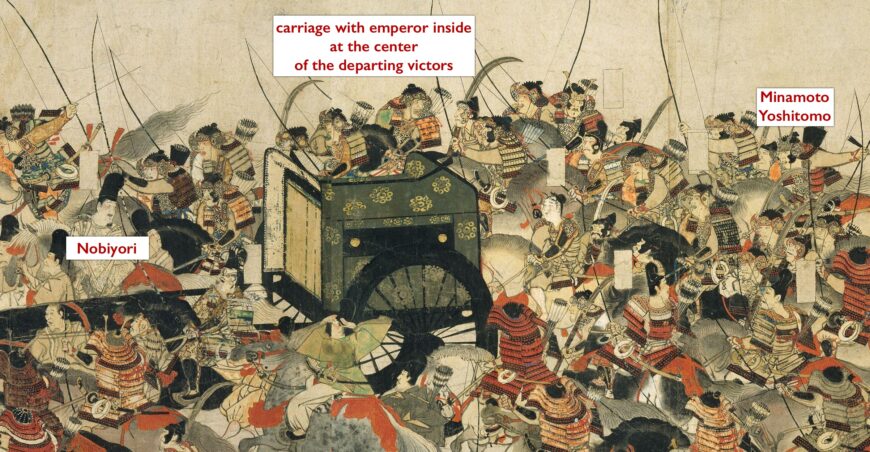

Nobuyori (who is seizing power), Minamoto Yoshitomo (head of the Minamoto clan), and the carriage led by an ox appear multiple times, orienting the eye and organizing the sweep of events.

Ox carriage at the opening of the scene (detail), Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Opening the action (above), we see the elegant carriage guided by a groom and pulled by an ox that will carry off Go-Shirakawa (the retired emperor). Notice the distinctive pattern of the carriage.

The carriage is knocked about, Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Then we see the same ox carriage knocked about with others in the crush of fighting as they approach the palace wall (above).

Nobuyori (left) on the veranda ordering the former emperor into the carriage and Minamoto Yoshitomo on horseback, distinguished by a distinctive horned helmet, behind the carriage (and to the right) as it crashes onto the veranda. Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Then on the veranda we see Nobuyori in colorful armor ordering the former emperor Go-Shirakawa into the carriage.

Departing victors (detail), Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

We see the carriage again in the surge of departing victors, where two soldiers lolling on top lend an air of indignity and insult to the retired emperor inside. Nobuyori, now in court robes and on horseback, appears in front, glancing back at the carriage. Minamoto Yoshitomo, appears again in his distinctive horned helmet brandishing a bow and arrow, cantering behind the carriage in the departing crowd.

Tumult at the palace gate, note the two women (top left) distinguished by flowing hair and aided by an attendent, fleeing the battle as fast as their voluminous robes will allow (detail), Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The remainder of the Heiji Rebellion story appeared on other emaki in the set, now mostly lost: the kidnapping of Emperor Nijô, the slaughter of another noble household, Nobuyori forcing Nijô to appoint him chancellor, Taira Kiyomori’s return to decimate the schemers, and finally Kiyomori’s mistake—banishing rather than executing several of Minamoto‘s sons. Minamoto no Yoritomo and his brother Yoshitsune would return years later to destroy the Taira clan in the Gempei War and found the first of four military governments of the Shōgunate that ruled Japan from 1192 until 1867. Emperors and nobles remained in Kyoto, but were politically powerless. Feudal culture came to a violent end in 1868 at the hands of other samurai clans. They brought the young emperor Meiji into a new role as the monarch (really a figurehead) of a modern nation. Over the Meiji era’s early tumultuous decades many spectacular works of art left Japan to join important collections in the West. The Night Attack at Sanjô Palace, once owned by a powerful samurai family, came into the possession of an influential American who brought it home to Boston. It has been a highlight of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston since 1889.

Calligraphy at the beginning of the scroll (detail), Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace, Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji monogatari emaki) Japanese, Kamakura period, second half of the 13th century, 45.9 x 774.5 x 7.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The scroll’s text:

“At about the hour of the ox (2 am) on the ninth day, Lord Nobuyori proceeded with several hundred mounted soldiers to the Sanjō Palace, the residence of the Retired Emperor, and said, ‘Since I have heard that I am to be struck down, I intend to go to the east. I have served you close at hand for years and have been favored more than others by Your Majesty, and so it is indeed sad for me to part from my lord and abruptly leave the capital.’

Then the Retired Emperor said, ‘What sort of an affair is this? Who would strike you?’ But without hearing him out, soldiers hastily brought up the Imperial carriage. “You must hasten into the Imperial carriage. Now, set fire to the Palace,” ordered Nobuyori, and His Majesty unwillingly got into the Imperial carriage. Jōsaimon’in had already gotten in. It was Lord Moronaka who had brought up the Imperial carriage. Nobuyori, Yoshitomo, Shigenari, the Sado Vice-Minister of Ceremonial, Minamoto Mitsumoto, the Commisioner of the Police, Suezane, the former Commisioner of Police, and the others surrounded the Imperial carriage and took it to the Imperial Palace. They shoved him into the Palace Single-Copy Library, where Shigenari and Mitsumoto guarded him.

Soldiers blockaded the Palace on all four sides and set fire to it. Those who fled out they shot or hacked to death. Many jumped into the wells, hoping that they might save themselves. The ladies-in-waiting of high and low rank and the girls of the women’s quarters, running out screaming and shouting, fell and lay prostrate, stepped on by the horses and trampled by the men. It was more than terrible. No one knows the number of persons who lost their lives.

Some said that Yoshitomo had raised a rebellion and had broken into the Sanjō Palace in a night attack and set it on fire and that even the Retired Emperor had not escaped the flames. Some also shouted that His Imperial Highness had gone to the Imperial Palace. Consequently, the ‘Great Lord’ the Lord Chancellor, and all the other nobles and courtiers came in a crowd. the noise of their horses and carriages rushing back and forth was like thunder, and greatly did it resound both in heaven and on earth.

At the hour of the tiger (4 am) the same night, they seized the dwelling of the Shinzei at Anegakoji Nishinotoin and set fire to it. For the past three or four years arms had been banned, and the Empire had been at peace, but now suddenly this disturbance had broken out, and both the Imperial Palace and the capital were filled with soldiers. The noble and lowly lamented together, wondering what had happened.”

Translation from Reischauer & Yamagiwa, Early Japanese Literature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951): pp. 451–53.

Notes:

[1] Japanese surnames come first and given names come second. Fujiwara and Taira are surnames. The Chinese characters used have different pronunciations that can appear at different times. “Minamoto” can be “Genji;” “Taira” can be “Heike.”

Cite this page as: Dr. Hannah Sigur, “Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace,” in Smarthistory, April 1, 2016, accessed June 5, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/night-attack-on-the-sanjo-palace/.