The Antikythera Youth, 340–330 B.C.E., bronze, 1.96 m high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Map indicating the location of Antikythera and the wreck off its northeast coast (source: Alison Mackey/Discover/NASA)

In 1900, sponge divers working off the northeast coast of the Greek island of Antikythera made one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the century. Dispersed along the seafloor, at a depth of 42–52 meters (about 137–171 feet), were the remains of wooden planking from the hull of an ancient freighter and an impressive array of objects that never made it to their intended destination. This discovery, which catalyzed the development of the discipline of underwater archaeology, was the first of a series of ancient shipwrecks to be identified in the Eastern Mediterranean over the course of the 20th century. Its historical significance cannot be overstated.

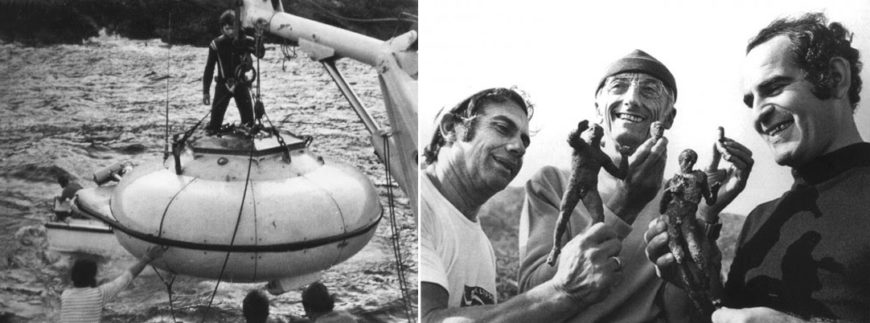

Left: the bathyscape photographed aboard the oceanographic vessel Calypso. Right: Albert Falco, Jacques-Yves Cousteau, and Lazaros Kolonas presenting bronze statuettes found in the 1976 salvage campaign. Below, footage from the 2019 expedition of the Return to Antikythera project (photo: Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports)

Most of the salvaged portions of the ship and its contents were recovered in two separate campaigns: the first by Greek and foreign divers in 1900–1901; and the second with the additional deployment of a vacuum pipe and bathyscape carried aboard Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s research vessel Calypso in 1976. Expert examination of the finds has refined our knowledge about many aspects of the ancient Mediterranean world, from shipbuilding techniques and seaborne trade in art and other commodities to the state of scientific knowledge in the tumultuous final decades of the Hellenistic period (323–31 B.C.E.).

Despite these herculean efforts, an uncertain proportion of the wreck still lies at the bottom of the sea. In 2014, a third campaign of exploration was launched with the goal of using advanced technologies to map the site and to rescue additional artifacts from the depths.

Video of the 2019 Return to Antikythera expedition

This project (Return to Antikythera), in conjunction with the ongoing scientific investigation of the famous Antikythera Mechanism (see below), promises to enhance our understanding of this fleeting moment of ancient Mediterranean history—a moment that would be irretrievably lost were it not for an ill-fated storm.

The Mediterranean and long-distance trade

When we imagine the ancient sea, we should populate its waters with hundreds, even thousands, of oar- and sail-propelled vessels of different kinds and sizes, ranging from small fishing skiffs to large cargo ships, crisscrossing one another in route to one of the Mediterranean’s innumerable ports and harbors. In addition to its coastline, which stretches over 46,000 km (28,000 miles) and three continents, the Mediterranean is dotted by thousands of islands and islets, some separated only by a few miles. Some sea travel was relatively short: a skip down the coast or perhaps darting from one island to another in the same cluster. Other voyages were more extended and thus riskier. As they were charting their course, ancient navigators drew upon their common knowledge of sea currents, tidal flows, seasonal weather patterns, and underwater hazards. Then as today, boats would have taken similar routes to similar destinations. Communities living along these well-trafficked routes would have regularly observed the passage of ships, especially from spring to autumn (when the sea conditions were most favorable).

Gold earrings with inlaid semi-precious stones and pearls and pendant figures of Eros, 2nd–1st century B.C.E. (photo: Kostas Xenikakis/National Archaeological Museum, Athens)

Archaeologists around the globe have turned up evidence of long-distance trade in the form of materials and objects whose physical properties or stylistic features indicate a distant origin. Take, for example, two earrings found in the Antikythera Shipwreck. Although originating from two different pairs, they exhibit similar technical and decorative features that suggest a common cultural origin. Most notable are the small pendant figurines of Eros, the Greek god of love and sexual desire, shown playing a stringed instrument or supporting an opened folding mirror above the head. The adornment of the jewels with this god (and cosmetic elements like the mirror) correspond to Greek cultural ideas and attitudes about the role that bodily adornment plays in feminine beauty. Yet, these earrings could not have been made without access to raw materials: gold, pearls, garnets, and emeralds (or prase). These materials cannot be found in a single location in the Eastern Mediterranean and indeed some are scarce or absent in lands inhabited by Greeks. The jewelers who made these objects had to acquire materials from various, non-local sources. Indeed, the Hellenistic period saw an influx of (semi-)precious stones from points east. Archaeologists and art historians therefore pay equal attention to the materiality of objects, as it may also reveal (as with the earrings) trade across geographic and even cultural boundaries and thus enhance our appreciation of objects’ significance or value.

In some contexts, such as Mesopotamia and Egypt, more granular documentation of trade in administrative archives or business letters and accounts have been preserved on clay tablets or papyri. But in most cases, the trade process itself leaves little direct trace in the archaeological record. When it does, it is usually thanks to a disaster that fixes a fleeting moment in time and space. Seafaring entailed many hazards to a ship’s crew, cargo, and the merchant’s bottom line: delays (such as inclement weather), piracy, and wrecks. In the case of the ship off the coast of Antikythera, it was likely caught in an intense storm that drove it aground. The seas in this area are notoriously temperamental.

Thousands of shipwrecks have thus far been identified, at varying depths, in the Mediterranean. Despite their elevated number, these wrecks represent but a small fraction of the ships that plied the seas over the millennia. Based on their associated finds, shipwrecks seem to have been most frequent between the 1st century B.C.E. and the 1st century C.E. This suggests that maritime trade also reached its peak in these centuries. It is to this period—and more specifically to 60–50 B.C.E.—that the Antikythera shipwreck belongs.

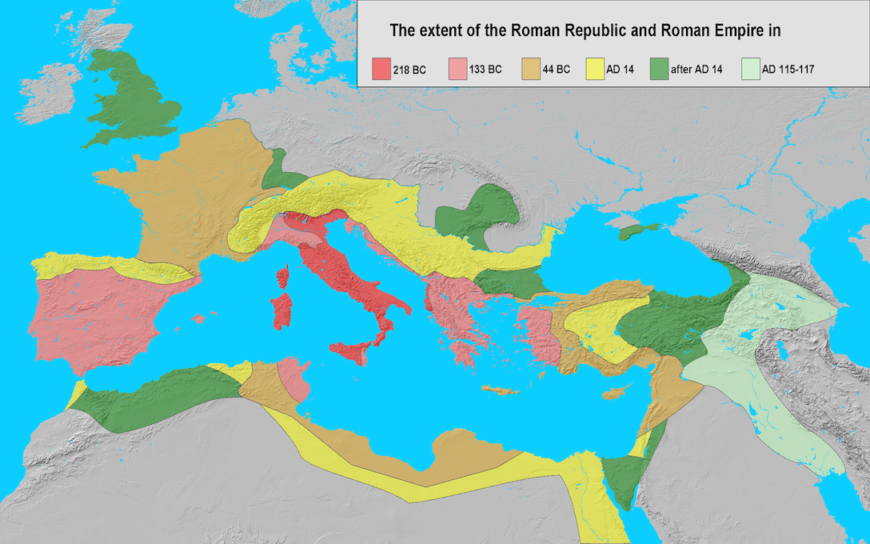

Schematic map showing the territorial expansion of Rome from the Middle Republic to the death of the Emperor Trajan (map: Varana, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A taste for Greek art

The first century B.C.E. was one of tumult and dramatic change. It saw the Roman Republic endure through a series of civil wars while leveraging its political, military, and commercial power to eclipse its remaining rivals in the Hellenistic East (especially the Pontic kingdom of Mithridates VI Eupator and Egypt under the famous Ptolemaic ruler Cleopatra VII Philopator) and ultimately establish imperial rule over them. Through exposure to the steady stream of loot into Rome as a result of military conquests, Roman elites had acquired a keen appetite for art and luxury goods produced in the Eastern Mediterranean, to be displayed or consumed in their villas as a mark of their status and cultural sophistication. This appetite drove the importation of all manner of items to Italy and the development of a market for reproductions or “historicizing” reinterpretations of well-known Classical and Early Hellenistic sculptural works or types.

Elites could purchase luxuries on the open market or charter their own shipments. The published letters of the Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero reveal that this famous orator entrusted his friend Titus Pomponius Atticus to act as his agent in acquiring Greek artworks for one of his villas. [1] Cicero’s correspondence with Atticus is roughly contemporary with the Antikythera shipwreck; it is possible that the ship that wrecked off Antikythera was a private charter of goods.

Among the identified shipwrecks from this era, most carry a homogeneous cargo of transport amphorae or other ceramic storage vessels that were valuable for what they contained: grain, oil, wine, perfumes and ointments, or condiments like fermented fish sauce. These more typical cargos testify to the existence of an extensive trade in staple and luxury foods and items of personal care. But a few exceptions, like the wreck off Antikythera, yielded additional artifacts of interest: works of art and the unparalleled Antikythera Mechanism—the world’s oldest known analog computer.

Objects found in the Antikythera shipwreck. Left: fragment of the metal revetment from the side end of a couch headrest, 150–100 B.C.E. (photo: Giovanni Dall’Orto). Center: Assorted glass bowls, first half of the 1st century B.C.E. (photo: Kostas Xenikakis/National Archaeological Museum, Athens). Right: Assortment of intact and fragmentary transport amphorae from varying origins (Ephesus, Kos, and Rhodes), first half of the first century B.C.E. (photo: Kostas Xenikakis/National Archaeological Museum, Athens)

Objects from the Antikythera Shipwreck

Scholars have assigned the objects from the Antikythera Shipwreck to four general categories:

-

Marble sculpture (Herakles?) from the Antikythera Shipwreck (photo: Gary Todd, public domain)

Parts of the ship, which show that it was a large freighter constructed in the shell-first technique and that its wooden planks were lined with lead to insulate it from the water and wood-boring microorganisms; estimated carrying capacity: 300 tons!

- Personal effects of crew members or passengers, which offer a precious glimpse into life on the seas; these included things like fishing gear, cooking pots and dishes (some with signs of use), forms of entertainment (a musical instrument and game pieces), jewelry, coinage, and even human bones belonging to at least four different individuals: two adult men, perhaps one adult woman, and an adult of uncertain sex.

- Large- and small-format bronze and marble statues; these constituted the most significant proportion of the cargo in mass and number, and thus were probably the main attraction of the shipment

- Other luxury or specialty items, such as the Antikythera Mechanism, bronze couches/beds, silver and glass vessels and utensils, red-slipped dish ware, and organic foods and substances (which are implied by the presence of ceramic containers appropriate for their storage and transport)

Red-slipped hemispherical cup and red-slipped plate of the Eastern Sigillata A type. These and other red-slipped dishware from the wreck are dated generally to the 1st century B.C.E., but the presence of a thin orangish slip that is easily worn away and a horizontal darker red streak (from double-dipping the vessels into the slip) suggests that these vessels date to the third quarter of the 1st century and probably closer to 50 B.C.E., when red-slipped dishware reaches its greatest geographic distribution (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Kostas Xenikakis)

Many of the objects in the cargo have been traced back to production centers in the Hellenistic East (Syria, Alexandria, and perhaps Pergamon and Ephesus). While this might suggest that the boat made several stops before heading to its final destination, the goods were probably loaded all at once at a major commercial port like Pergamon, Ephesus, or Delos (where goods from all over converged). If the shipwreck indeed dates to after 69 B.C.E.—as suggested in particular by the red-slipped tableware (dated to as late as the mid-first century)—then Delos is a less attractive candidate. In spite of the tax-free status that Delos had enjoyed since 167 B.C.E., the island’s standing diminished after its pillaging for a second time by pirates during the Third Mithridatic War (73–63 B.C.E.). The comparative scarcity of objects from the Roman West among the ship’s contents is additional evidence that the voyage embarked from somewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean and was bound for an Italian port, probably Puteoli near the modern city of Naples. At the time of the shipwreck, Puteoli was the principal commercial port in Roman Italy, owing to its natural harbor that could accommodate great numbers of ships, including large freighters. Its proximity to the luxurious Campanian villas of the Roman elite only added to its convenience and appeal.

Antikythera Youth, 340–330 B.C.E., bronze, 1.96 m high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An over-life-size bronze sculpture

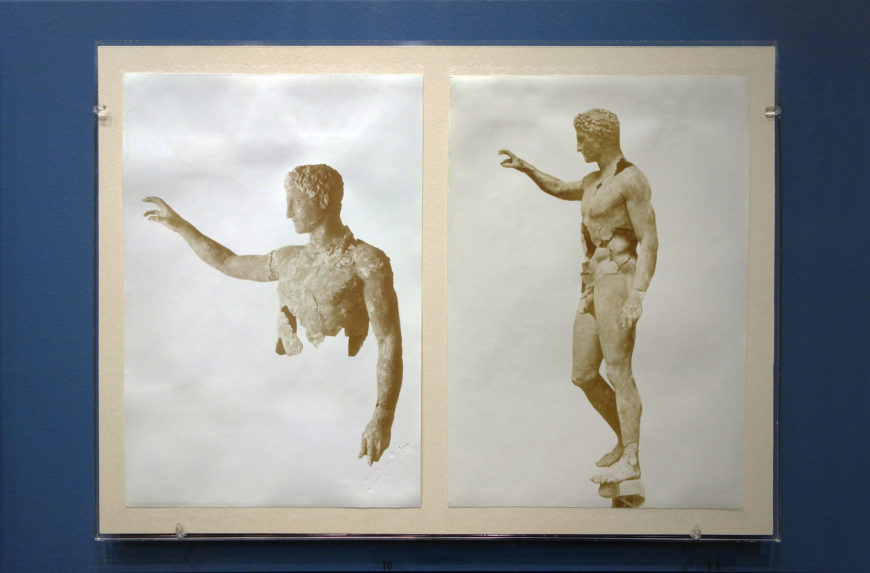

Antikythera Youth photos before restoration, 340–330 B.C.E., bronze, 1.96 m high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Easily the most iconic work of art to emerge from the wreck is a nearly complete, (now) restored bronze known as the Antikythera Youth. This over-life-size sculpture was one of roughly four dozen bronze and Parian marble representations of gods, heroes, mortals, and horses that were uncovered in varying degrees of fragmentation and material degradation.

Lysippos, Apoxyomenos (Scraper), Roman copy after a bronze statue from c. 330 B.C.E., 6′ 9″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While most of these sculptures are contemporary Late Hellenistic creations, the stylistic and technical features of the Youth suggest that it was an original work of the Late Classical period (340–330 B.C.E.). While the heavy musculature in the Youth’s torso and the manipulation of the contrapposto bodily scheme suggest a derivation from the style of the High Classical sculptor Polycleitus, the figure’s proportionately smaller head and thinner legs, deeper set eyes, and more spatially dynamic pose correspond to trends observed in later fourth-century works (like those by Praxiteles, Scopas, and Lysippos). As was typical of large-scale Greek bronzes, the Youth was made of separately hollow-cast components that were soldered together and enhanced with additional embellishments (like inlaid eyes of glass or colored stones). As additional corroboration of the Late Classical dating, a scientific test of the chemical composition of the bronze determined that it consisted of an 86/14 alloy of copper and tin. No traces of lead–which is irregular in Greek bronzes prior to the Hellenistic period–were detected. The proposed date of 340–330 B.C.E. would make the Antikythera Youth the oldest known artifact from the cargo—a nearly three-hundred-year-old antique when it was loaded into the hull!

Scholars have never reached a consensus on the identity of this nude Youth. The objects that he once held would have served as iconographic attributes. The two most popular identifications are Paris presenting the Apple of Discord or Perseus clutching the severed head of Medusa. However, neither of these identifications are entirely convincing because other salient elements of their respective iconographies are absent: for example, Paris’s Phrygian cap and Perseus’ winged sandals and the helm of invisibility lent to him by Hades.

Antikythera machine, recovered fragments (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Antikythera Mechanism

Equally famous, on account of its technological and scientific sophistication and uniqueness, is the Antikythera Mechanism. Ongoing investigation of this fascinatingly complex object by the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project has yielded new insights that have transformed or nuanced our understanding of its origins and purpose. According to the current reconstruction, the Mechanism consisted of a wooden housing mounted with inscribed copper alloy plate displays on two opposite faces, the dials and indicators of which were moved by an intricate interior network of hand-powered metal gears and axles (using a crank or knob). The user could input a particular date in the calendrical year and the Mechanism would calculate and display synchronous astronomical information, like the positions of the sun and moon (or vice versa). While a later second-century B.C.E. construction date has often been favored, more recent examination of the Greek inscriptions on its face plates suggests that the Mechanism dates to no more than a few decades before the wreck. Whatever the dating, the Mechanism is an eloquent attestation of the state of Greek engineering, mathematics, and astronomical science in the Late Hellenistic era.

Statuette of a Nude Youth, late 2nd century B.C.E., found in the Antikythera Shipwreck (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports; photo: Kostas Xenikakis)

A spinning statuette

A fitting coda to this brief exploration of the Antikythera Shipwreck is a bronze statuette of a young man that was found along with its nesting cylindrical plinth and cubic base. This classicizing nude male evidently could be made to spin by means of a crank installed in its base! Here we find the marriage of the sculptural art of the Antikythera Youth and the basic rotary mechanics of the Antikythera Mechanism (though here perhaps predating the latter!). Hellenistic- and Roman-era literature speaks of three-dimensional works of art that—much to the amazement of their audiences—appeared to move on their own. Famous examples of such automata—like the bizarre mechanical snail that the tyrant Demetrius of Phalerum had constructed for a religious procession in 309/308 B.C.E., or the diverse contraptions described in the treatises of the engineer Heron of Alexandria (Pnuematica and Automatopoetica)—do not survive. [2] Although the scale and technical complexity of the Antikythera statuette are much more modest, the work nevertheless reflects the Hellenistic flair for a peculiar form of illusionistic artifice that was enabled by advances in engineering and the mechanical sciences. Clearly, the Roman client(s) for whom this and the other objects were destined was/were well-versed in the prevailing tastes of their time.

[1] Letters to Atticus 1.8.2 and 1.9.2

[2] For more on the mechanical snail, see Polybius’s Histories 12.13.11

Cite this page as: Dr. Michael Anthony Fowler, “The Antikythera Shipwreck,” in Smarthistory, August 11, 2021, accessed May 29, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-antikythera-shipwreck/.

The Antikythera Youth, 340–330 B.C.E., bronze, 1.96 m high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens), an ARCHES video. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “The Antikythera Youth,” in Smarthistory, July 19, 2020, accessed May 29, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/antikythera-youth/.