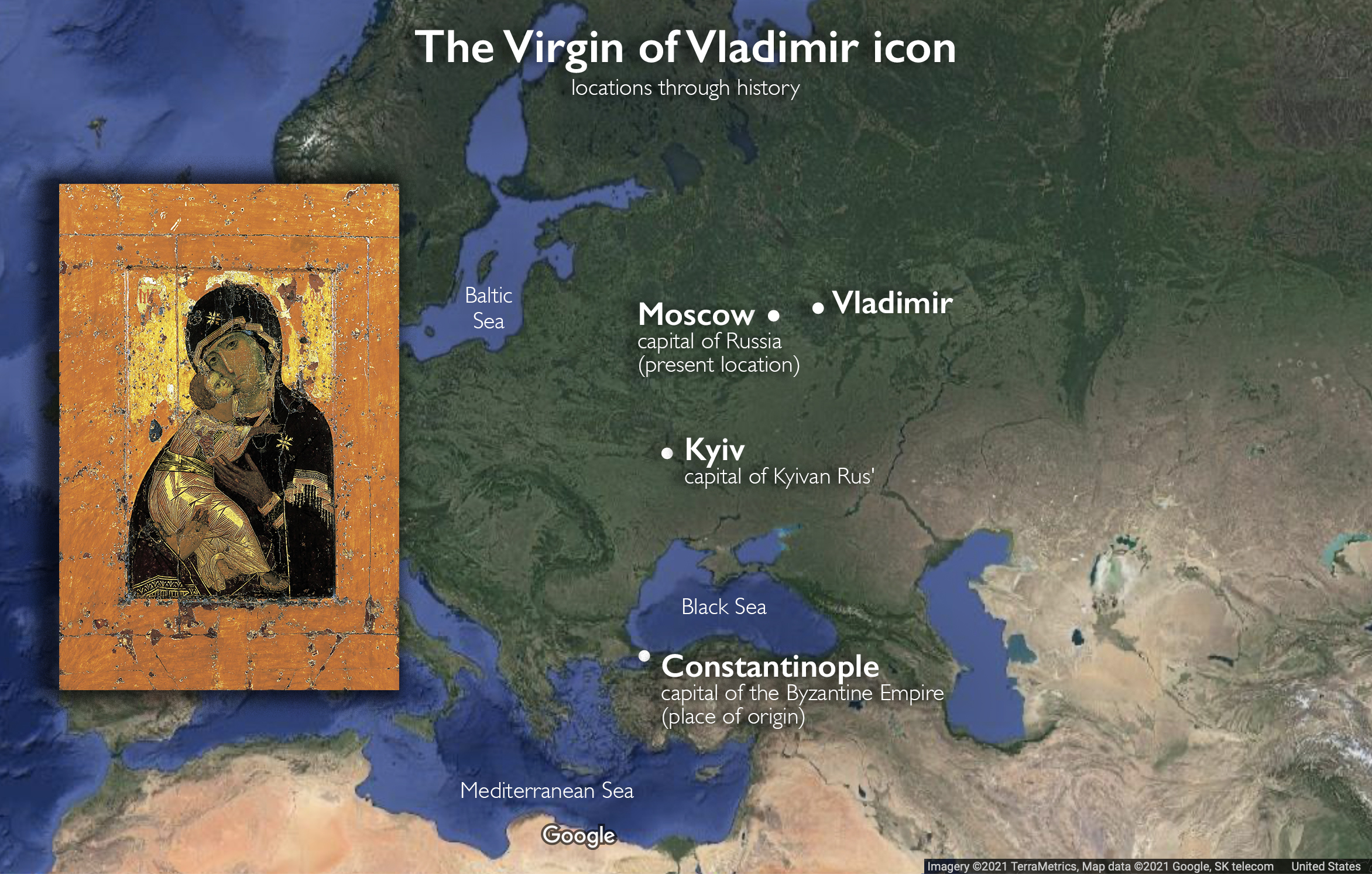

Virgin of Vladimir, 12th century with later repainting, tempera on wood (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

One of the most beloved artworks in Russia is a tempera on wood icon known as the Virgin of Vladimir, or Vladimirskaya. It presents a common composition known as the Virgin eleousa (“compassionate”), which shows Mary and Jesus in tender embrace, their faces pressed together. The Virgin gazes out at us, commanding our attention, but her hands seem to gesture toward her son, destined to die on the cross and rise from the dead as the savior of humankind. Through the centuries, many miracles have been attributed to this icon, and as a result, numerous patrons and artists have sought to produce copies of it.

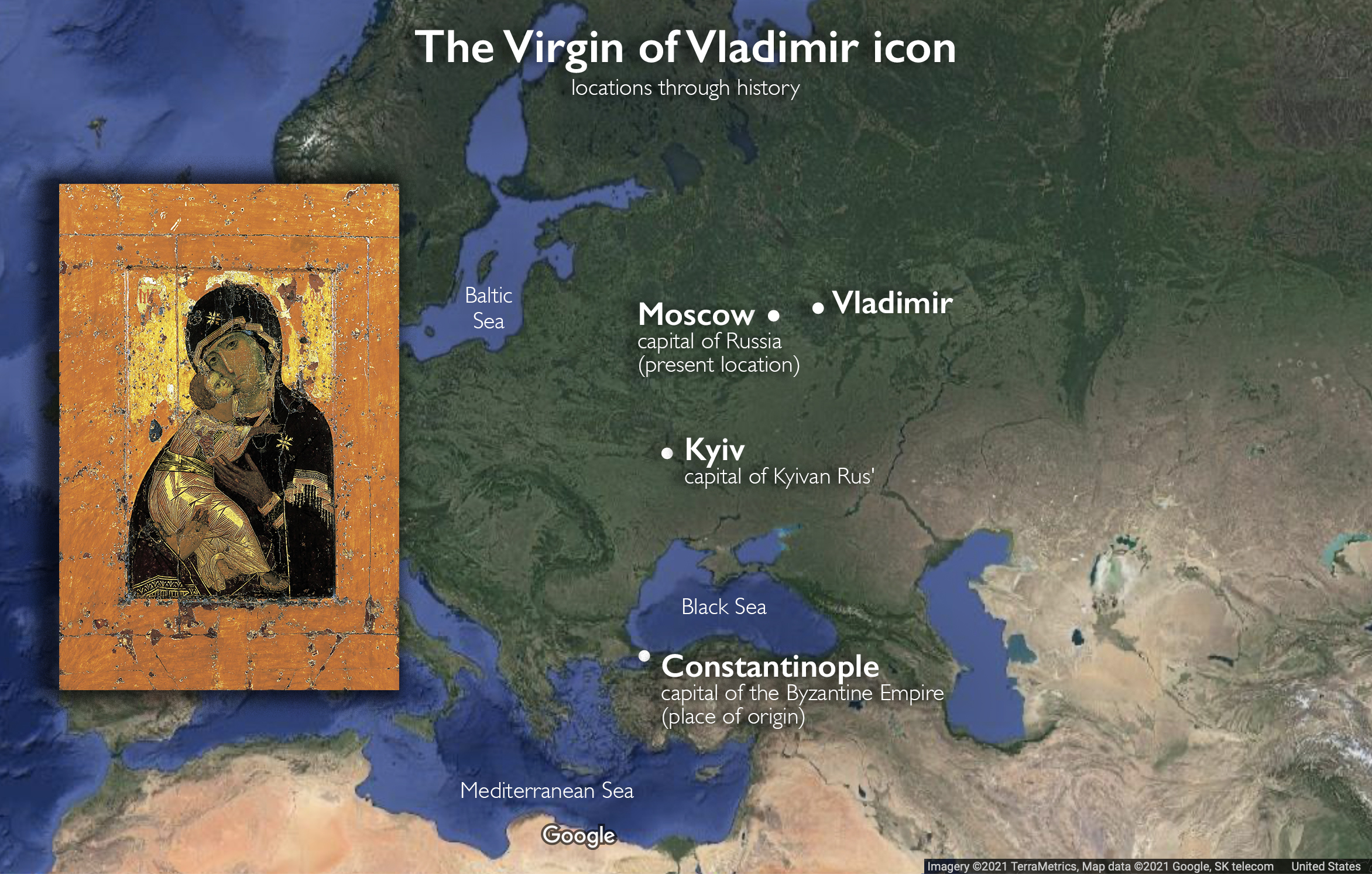

Locations of the Virgin of Vladimir icon (underlying map © Google)

But despite the Virgin of Vladimir’s enduring religious and cultural importance in Russia, the icon is not Russian in origin. It was likely painted in the twelfth century in Constantinople (Istanbul), capital of the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire, and brought to Kyiv, capital of Kyivan Rus’, as a diplomatic gift around 1131. Later, the icon was transferred to the city of Vladimir (hence its name), and eventually to the Russian capital of Moscow, where it still remains.

The Virgin of Vladimir’s journey from Constantinople to Kyiv, and eventually, to Moscow, is part of a larger story of the conversion of Kyivan Rus’ to the Orthodox Christianity of the Byzantine Empire in the tenth century and Moscow’s subsequent rise as a new center of power in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. While neither the Byzantine Empire nor Kyivan Rus’ survive today, works of art and architecture like the Virgin of Vladimir can help us understand the relationship between these medieval states, as well as their contested legacies in today’s world.

The Byzantine Empire and Kyivan Rus’

Kyivan Rus’ emerged as a powerful confederation of city-states during the second half of the ninth century in Eastern Europe, where rivers helped link the Baltic Sea with the Black Sea and facilitated trade with Constantinople, the wealthy capital of the Byzantine Empire. The capital of Kyivan Rus’ was Kyiv on the Dnieper River, which is today the capital of Ukraine. The name “Kyivan Rus’” refers both to the state and its people.

Map of the Byzantine Empire and Kyivan Rus’ (underlying map © Google)

A modern monument to prince Vladimir I overlooks the Dnieper River in Kyiv, Ukraine, (photo: Library of Congress)

Kyivan Rus’ was sometimes a trading partner and other times an enemy of the Byzantine Empire. But in 987, Prince Vladimir I of Kyiv, ruler over Kyivan Rus’, formed an alliance with the Byzantine emperor Basil II, converting from paganism to Christianity and marrying Basil II’s sister Anna in 988. Historical texts describe the subsequent conversion of Vladimir’s formerly pagan subjects by mass baptism in the Dnieper River in Kyiv. With its conversion to the Orthodox Christianity of the Byzantines, Kyivan Rus’ now began appropriating and adapting Byzantine art and architecture for itself.

St. Sophia, c. 1037 (with later additions), Kyiv (photo: Daniel Kraft, CC BY-SA 3.0)

St. Sophia, Kyiv

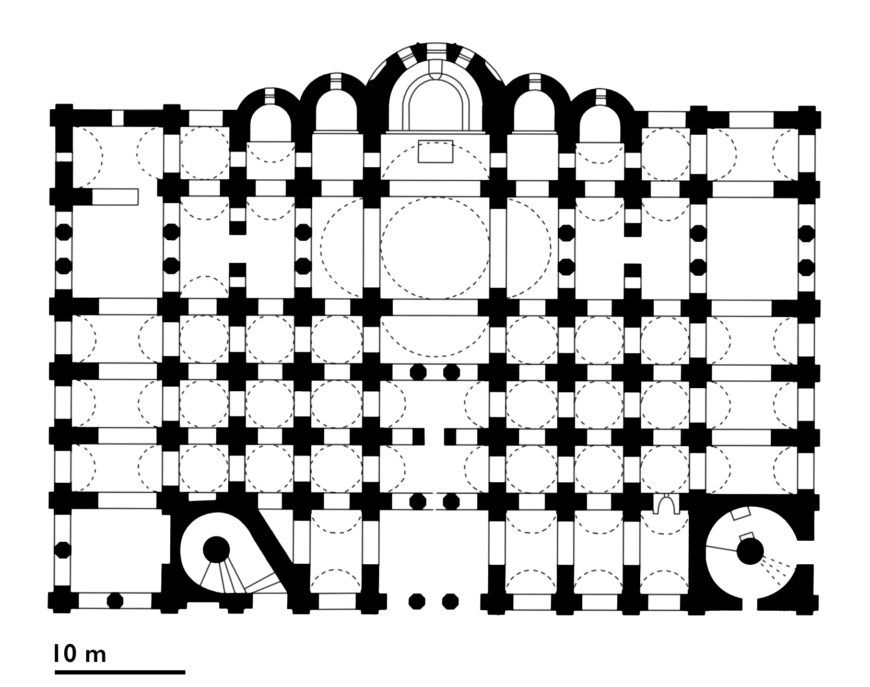

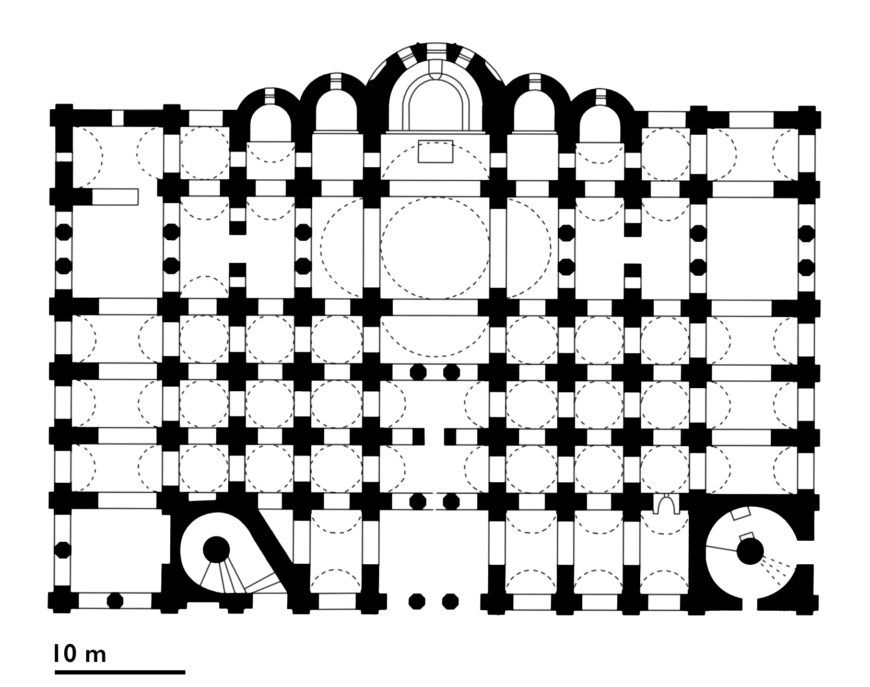

Plan of St. Sophia, Kyiv, c. 1037 (Evan Freeman, redrawn after John Lowden, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Wishing to emulate the Byzantine capital of Constantinople and its cathedral Hagia Sophia (dedicated to Christ as “Holy Wisdom”), Vladimir’s son Yaroslav expanded Kyiv and built a magnificent new church to function as the city’s main cathedral, which he likewise dedicated to St. Sophia (“Holy Wisdom”) in imitation of Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia. St. Sophia in Kyiv illustrates how Kyivan Rus’ appropriated the art and architecture of the Byzantine Empire while also making it their own.

Built c. 1037, Kyiv’s St. Sophia was likely the product of collaboration between Byzantine and local craftsmen. The core of St. Sophia takes the form of a typical Middle Byzantine cross-in-square church, incorporating additional aisles and galleries to accommodate a large cathedral congregation, though still falling short of the astonishing scale of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Kyiv’s St. Sophia was probably finished in the 1040s and even its first bishop, Theopemptos, came from Constantinople. St. Sophia in Kyiv still stands today, albeit with later restorations and additions.

The interior of St. Sophia displays mosaics and frescoes—hallmarks of Byzantine church decoration—though the former are better preserved than the latter. And although church services in Kyivan Rus’ were celebrated in Church Slavonic, a language whose written form was first developed by Byzantine missionaries in the ninth century, St. Sophia’s mosaics are labeled in Greek, the language of Byzantium.

Christ Pantokrator

Byzantine worshippers probably would have found the interior of Kyiv’s St. Sophia very familiar. As in contemporary Byzantine churches, such as Daphni monastery, a bearded Christ Pantokrator (“almighty”) reigns over the church from the central dome. Christ is surrounded by angels with large wings in imperial garb. Apostles fill the spaces between the windows in the drum that supports the dome and the four evangelists (authors of the Gospels) appear in the pendentives just below the windows.

The Annunciation

The mosaics in the bema where the altar is located similarly mirror contemporary Byzantine churches and point to the function of this part of the church as the place where the Eucharist was celebrated. Gabriel and the Virgin enact the Annunciation from either side of the bema. The angel announces to the Virgin that she will give birth to Jesus, suggesting a parallel between Christ’s incarnation (becoming flesh and blood) through the Virgin and the Eucharistic bread and wine believed to become Christ’s body and blood on the altar below.

Virgin orans

A towering Virgin orans (about 5.5 meters tall) looms against the gold ground of the apse. She stands on a gold platform and raises her hands in prayer beneath large Greek characters that identify her as the “Mother of God.” This mosaic echoed similar images of the Virgin installed in churches and the palace in Constantinople following Iconoclasm, which were associated with imperial power and authority. A large inscription frames the Virgin at Kyiv with the words of Psalm 45:6, which speak of a God-protected city: “God is in its midst; it shall not be shaken; God will help it in the morning.” [1]

The Communion of the Apostles

Below the Virgin, Christ presides at the celebration of the Eucharist in a scene known as the “Communion of the Apostles,” which became a common feature in Byzantine churches at this time, and which paralleled the celebration of the Eucharist unfolding at the altar below. Although reminiscent of the Last Supper, this image anachronistically depicts Christ presiding at a celebration of the Divine Liturgy like a Byzantine priest with all the trappings of a contemporary church altar. This image must have helped connect the experiences of contemporary worshippers with these holy figures of Christ and his apostles from the past: as worshippers drew near to the altar to receive the Eucharist, they mirrored the apostles who similarly approached Christ in the mosaic above.

Perhaps surprising to modern viewers, Christ actually appears twice in this image. The artists have employed a common medieval visual device known as continuous narration in an attempt to depict two moments within one scene: on the left, Christ offers the Eucharistic bread to six of the apostles; on the right, he offers the Eucharistic wine to six more apostles.

Virgin and Child flanked by emperors Constantine and Justinian, Southwest vestibule mosaic, early 10th century, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Frescoes

Fresco depicting the imperial box at the hippodrome in Constantinople, 11th century, St. Sophia, Kyiv

Badly damaged frescoes decorating the galleries and turrets of St. Sophia—privileged spaces reserved for the prince—once displayed portraits of Yarloslav, his wife Irene, and their children. Yaroslav, now lost, was once shown offering a model of St. Sophia cathedral to Christ, much as the Byzantine emperors Constantine and Justinian offer models of Constantinople and Hagia Sophia to the Virgin and Child in a tenth-century mosaic in Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. The southwestern turret also displayed images of chariot racing in the hippodrome of Constantinople, further linking Kyiv’s cathedral and prince with the Eastern Roman capital and empire.

Icon with the Battle of Novgorod and Suzdal (The Miracle of the Icon of the Mother of God of the Sign), c. 1475 (Novgorod Integrated Museum-Reservation, Novgorod, Russia) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The fragmentation of Kyivan Rus’

Icon of the Virgin orans (Our Lady of the Sign), which is associated with the 1170 battle between Novgorod and Suzdal, on display in the cathedral of St. Sophia, Novgorod (photo: Дар Ветер, CC BY-SA 3.0)

By the middle of the twelfth century, Kyiv lost control over its expansive territories, and Kyivan Rus’ fragmented into several smaller states, which sometimes fought amongst themselves. This fifteenth-century icon from Novgorod depicts a battle in 1170 when forces from Suzdal laid siege to Novgorod (view locations on map). The main subject of this icon is itself another icon—in this case a miracle-working icon of the Virgin orans and Christ Child still preserved in Novgorod’s cathedral of St. Sophia—which, according to legend, played a pivotal role in the battle between Novgorod and Suzdal. This episode illustrates the importance that the holy images, or icons, of the Byzantine Empire came to play in the culture of Kyivan Rus’, and later, Russia.

Novgorodians process with the icon of the Virgin and Child (detail), icon with the Battle of Novgorod and Suzdal (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The icon is divided into three registers, in which the narrative of the battle unfolds from top to bottom. The top shows the people of Novgorod processing with the icon of the Virgin orans and Christ Child—a practice inherited from the Byzantines—into the fortified center of their city. The narrative unfolds from right to left. On the right, the clergy retrieve the sacred icon from the Church of the Savior on Elijah Street in the eastern part of the city. The clergy process through the middle of the scene and are received into the fortified center of the city where Novgorod’s cathedral of St. Sophia is located.

The army of Suzdal attacks Novgorod and strikes the icon of the Virgin and Child with an arrow (detail), icon with the Battle of Novgorod and Suzdal (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Novgorodians affixed the icon of the Virgin and Child to the walls of their city as a protection against the army of Suzdal. In the middle register, the army of Suzdal attacks from the right. One of their arrows strikes the icon of the Virgin and Child on the walls of Novgorod, seen in the upper left. According to legend, this prompted the icon of the Virgin to turn inward toward the city of Novgorod and weep. A supernatural darkness then covered the attacking army of Suzdal, and as a result, the attackers began attacking each other.

The army of Novgorod defeats the army of Suzdal with the help of the saints (detail), icon with the Battle of Novgorod and Suzdal (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the bottom register, the soldiers of Novgorod (left) triumphantly counterattack the army of Suzdal (right) with the help of the saints. The Archangel Michael—leader of the heavenly armies—swings his sword as he swoops down into the center of the scene. Additional haloed warrior saints gallop with the soldiers of Novgorod on horseback.

This icon and its subject illustrate the important role that the icons of Byzantium came to play in Kyivan Rus’ and Russia. More specifically, the battle between Novgorod and Suzdal illustrates the power ascribed to the Virgin and her miracle-working icons and parallels similar accounts from the Byzantine capital of Constantinople. At the same time, this icon with the Battle of Novgorod and Suzdal illustrates how the people of Novgorod adapted the arts of Byzantium to tell their own stories, in this case, the local miracle of the defense of their city.

The rise of Moscow, “Third Rome”

In the middle of the thirteenth century, Kyiv and many of its former territories fell to Mongol invaders, bringing an end to Kyivan Rus’. But after two centuries of Mongol rule in the region, the city of Moscow emerged as a new center of power. Moscow was a latecomer among the older cities of Kyivan Rus’, emerging in the twelfth century and gaining wealth and power in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Grand Duke of Moscow Ivan III “the Great” achieved independence from the Mongols around 1480 and established Moscow as the center of what now became known as “Russia.”

But as Moscow ascended, the Byzantine Empire declined. Constantinople (today Istanbul) fell to the Ottomans in 1453, ending the long history of the Eastern Roman Empire that had begun when emperor Constantine dedicated the capital city of Constantinople in 330, which he also referred to as “New Rome.” In the years that followed, Moscow increasingly viewed itself as successor to Byzantium and even began referring to itself as the “Third Rome.” [2] In 1472, Ivan III married Sophia Palaiologina, niece of the last Byzantine emperor, symbolically cementing the continuation of Byzantium in Russia.

Rublev’s Trinity

In addition to the Virgin of Vladimir, one of Russia’s best-known artworks—an icon of the Holy Trinity attributed to Andrei Rublev—dates from this period of Moscow’s ascent. Rublev was an influential Russian painter who probably lived from the 1360s until around 1430. Texts describe him painting the Cathedral of the Annunciation of the Moscow Kremlin with the Byzantine painter Theophanes the Greek, although these paintings no longer survive. Rublev probably painted his icon of the Trinity for the Trinity Lavra of Saint Sergius in Sergiyev Posad, an important monastery near Moscow, where it was part of a church iconostasis (the barrier that separates the sanctuary from the rest of the church).

Andrei Rublev, The Trinity, c. 1410 or 1425–27, tempera on wood, 142 × 114 cm (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

The harmonious colors and rhythmic contours of the symmetrical composition depict three angels who visited and were served food by the biblical patriarch Abraham and his wife Sarah in Genesis 18 in the Hebrew Bible or “Old Testament.”Christian theologians long interpreted this visitation of the three angels as an image of the Holy Trinity. Byzantine depictions of this event, as seen, for example, in the sixth-century mosaic at San Vitale, typically include both Abraham and Sarah, who play a central role in the biblical episode. But Rublev eliminated Abraham and Sarah from his icon, allowing the viewer to focus on the simplified composition of the three angels seated around an altar-like table. Rublev’s innovative icon reflects new Russian contributions to the Byzantine artistic tradition it inherited.

Hospitality of Abraham and Sacrifice of Isaac mosaic, San Vitale, consecrated 547, Ravenna, Italy

Contested legacies

The Byzantine Empire and Kyivan Rus’ do not survive, and their former territories are now divided among several states (as seen in the above maps). Consequently, the legacies of Byzantium and Kyivan Rus’ are often contested among these modern successor states, as the following two competing monuments illustrate.

Dedication of Monument to prince Vladimir I, Moscow, Russia, 4 November 2016 (photo: mos.ru, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In Moscow, Russia, the 2016 unveiling of a statue of the tenth-century prince Vladimir I of Kyiv caused international consternation. Located in the shadow of the Kremlin—Russia’s center of government—the statue of prince Vladimir towers over Moscow at nearly sixty feet tall. Vladimir holds a monumental cross with his right hand while his left hand clutches a large sword.

To many, Moscow’s menacing new prince Vladimir statue appears as a thinly veiled reference to the very similar, nineteenth-century statue of prince Vladimir that stands on the banks of the Dnieper River in Kyiv, Ukraine, the site of the baptism of Kyivan Rus’ into the Christianity of the Byzantines in the tenth century. The timing of Moscow’s installation of the new statue of prince Vladimir in 2016 was also significant: it coincided with Russia’s recent annexation of Crimea and ongoing armed conflict with Ukraine.

By installing the new statue of prince Vladimir in its capital, Russia seemed to lay claim to the historical legacy and perhaps even the former territories of Kyivan Rus’, even while some of those territories are part of other states, such as Ukraine.

While the Virgin of Vladimir, St. Sophia in Kyiv, and other works of art and architecture tell the story of the conversion of Kyivan Rus’ to the Christianity of the Byzantine Empire and the subsequent rise of Moscow as a new center of power, these more recent monuments speak to the enduring, if contested, legacies of Byzantium and Kyivan Rus’ in our world today.

Notes:

[1] Bissera Penthceva, Icons and Power: The Mother of God in Byzantium (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006), 76.

[2] The monk Philotheus (or Filofei) of Pskov first described Moscow as “third Rome” in a letter in 1510.

Additional resources

Smarthistory’s free Guide to Byzantine Art e-book

TED-Ed, Where did Russia come from? – Alex Gendler

Elena Boeck, “Simulating the Hippodrome: The Performance of Power in Kiev’s St. Sophia,” The Art Bulletin 91.3 (September 2009): 283-301

Helen C. Evans, ed., Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557) (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004)

Simon Franklin, “Rus’,” in The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, vol. 3, ed. Alexander P. Kazhdan, et al., (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 1818–1820

Martin Gilbert, The Routledge Atlas of Russian History, fourth edition (London and New York: Routledge, 2013)

Liz James, Mosaics in the Medieval World: From Late antiquity to the Fifteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Neil MacFarquhar, “A New Vladimir Overlooking Moscow,” The New York Times, 4 November 2016

Neil MacFarquhar, “Another Huge Statue in Russia? Not Rare, but Hugely Divisive,” The New York Times, 28 May 2015

Janet Martin, Medieval Russia, 980–1584, second edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007)

Olenka Z. Pevny, “Kievan Rus’,” in The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era A.D. 843–1261, ed. Helen C. Evans and William D. Wixom (New York: The Metropolitan Museum, 1997), pp. 280–287

Christian Raffensperger, “Rus: A Brief Overview,” Mapping Eastern Europe

Alice Isabella Sullivan, “A Key Monument of Medieval Rus’: The Cathedral of Saint Sophia in Kyiv”

Cite this page as: Dr. Evan Freeman, “Byzantium, Kyivan Rus’, and their contested legacies,” in Smarthistory, May 10, 2021, accessed May 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/byzantium-kievan-rus/.

A powerful Byzantine court official builds himself a dazzling burial chapel.

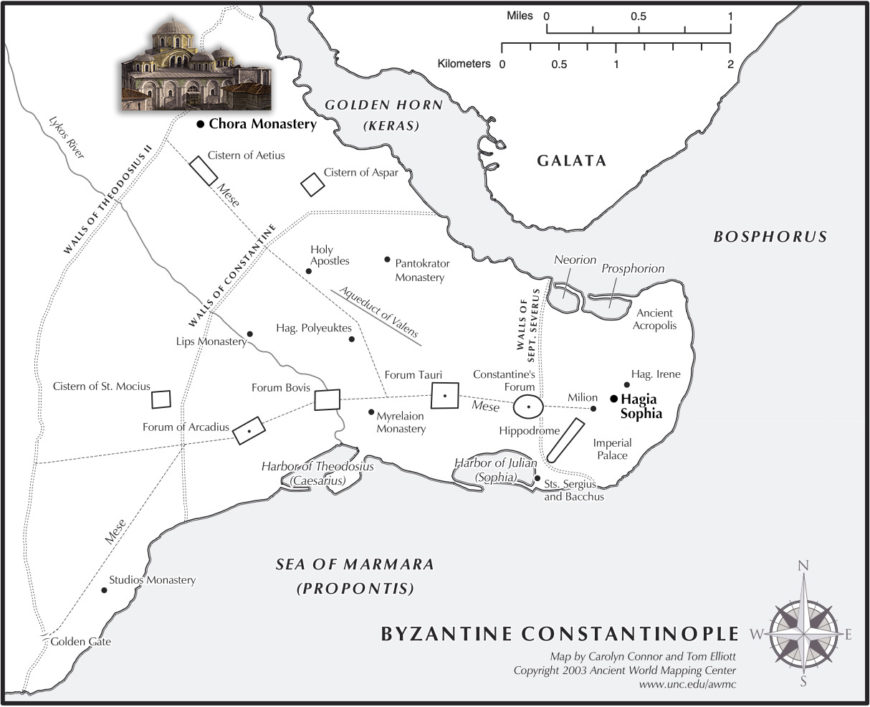

Chora church, Istanbul, renovated c. 1316–21

Christ Pantokrator mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An arresting, larger-than-life mosaic of Christ confronts viewers entering the Chora, a church that was once part of a monastery in the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul). The bust-length Christ, who blesses viewers with his right hand and holds a jeweled Gospel book in his left hand, appears in the lunette above the door between the outer and inner narthex (view location in plan). Such depictions of Christ are commonly known as the “Pantokrator,” which means “almighty.” This mosaic is one of many well-preserved mosaics and frescoes in this church, which date to the fourteenth century.

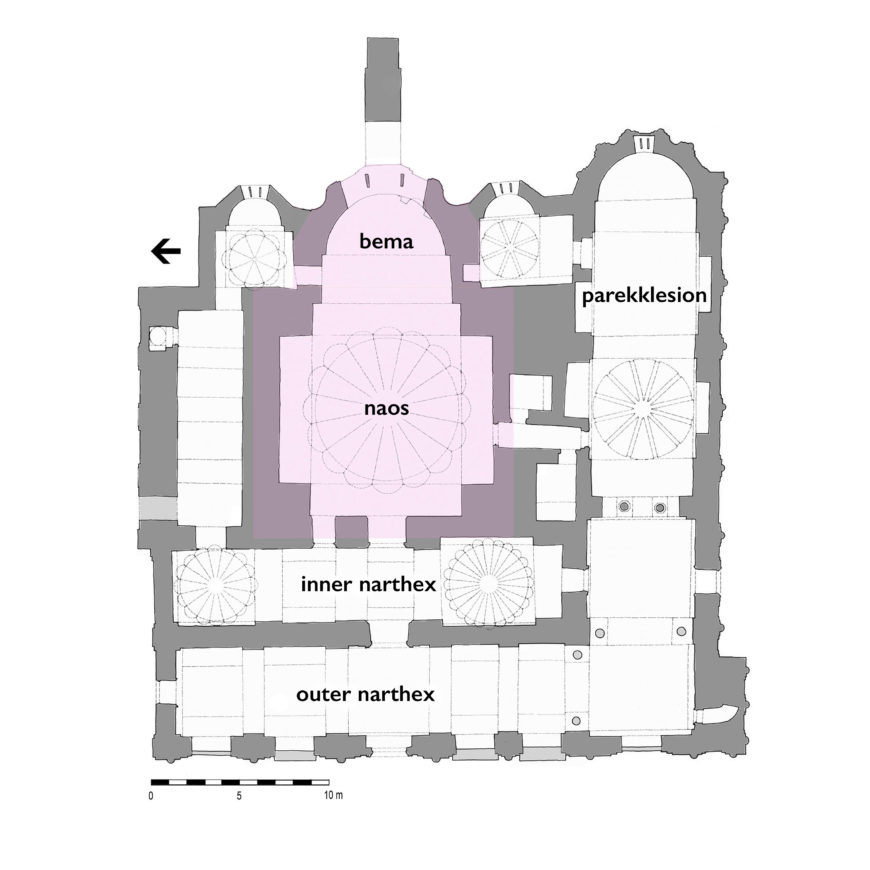

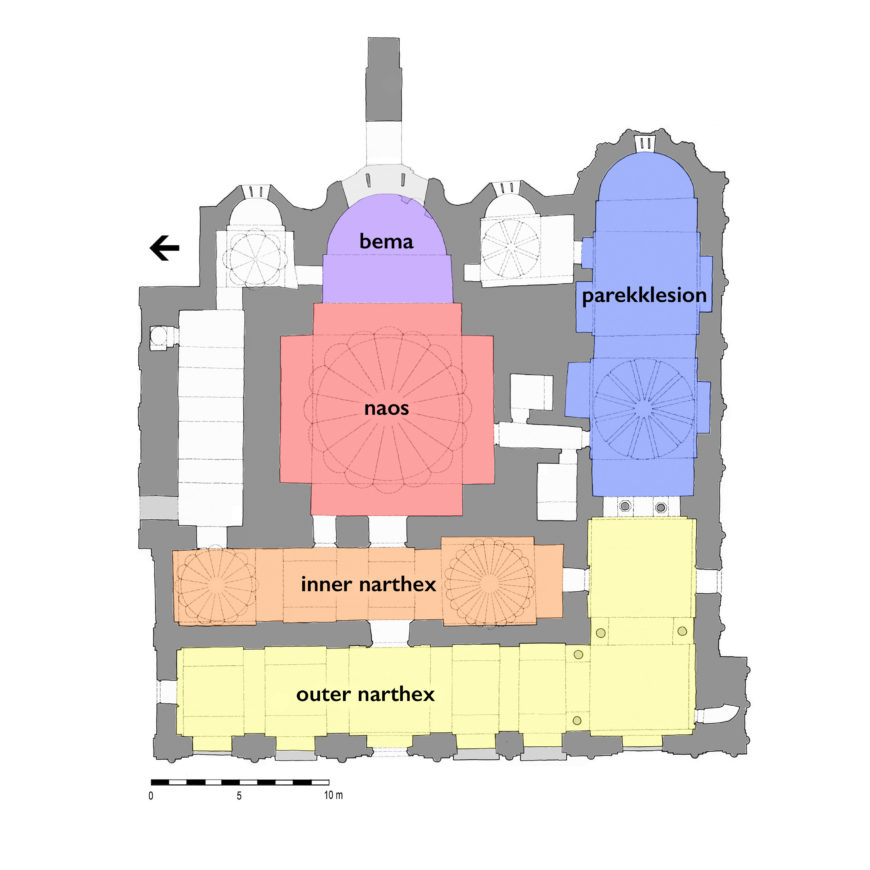

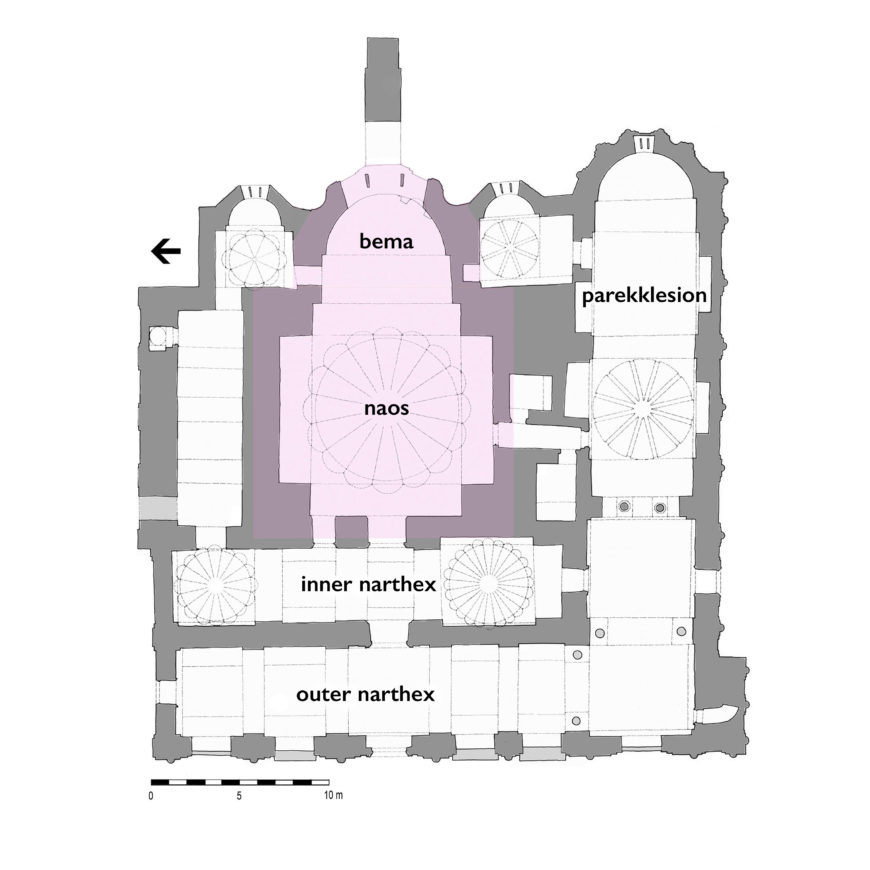

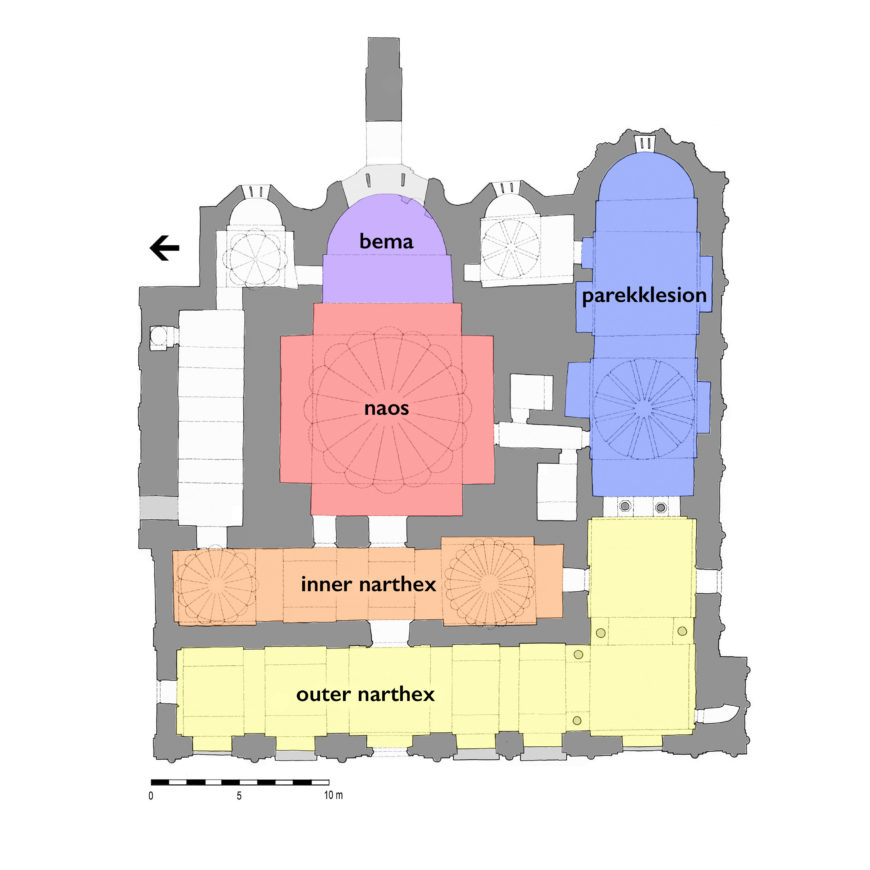

Chora church plan with the reused portions of the older naos highlighted in pink (© Robert G. Ousterhout)

Power and patronage

These mosaics and frescoes are the result of patronage by a wealthy intellectual and high-ranking official named Theodore Metochites, who restored the Chora c. 1316–1321, where he intended to be buried when he died. The early history of the Chora monastery is hazy, but the core of the current church was built in the twelfth century by Isaac Komnenos and fell into disrepair when Constantinople was sacked by western Europeans in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade.

About a century later, Metochites, a scholar of classical texts who donated his personal library to the Chora, held the position of Mesazon, or “prime minister,” to emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos, making him the second most powerful man in the empire. As ktetor (“founder,” or in this case, re-founder) of the Chora, Metochites oversaw the restoration of the twelfth-century church as well as the addition of inner and outer narthexes and a subsidiary chapel, or parekklesion, which served as a funeral chapel. The Chora’s rich mosaics and frescoes—among the finest examples of Late Byzantine art—illustrate Theodore Metochites’ ambition and his hope for salvation after death.

Christ Pantokrator mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Jesus Christ, land of the living

Despite his seemingly stern gaze, the entrance mosaic of Christ Pantokrator is optimistically labeled “Jesus Christ, the land (chora) of the living,” a play on the monastery’s name, which likely originally referred to its location “in the country” outside of the city walls built by emperor Constantine. This phrase—“land of the living”—comes from Psalm 116:9: “I walk before the Lord in the land (chora) of the living.” [1] The same text from Psalm 116:9 also appears in the Orthodox funeral service, which would have taken place in the Chora’s funeral chapel. So, by labeling Christ “land of the living,” Metochites put a spiritual spin on the Monastery’s name while also expressing hope for eternal life within the church where he planned to be buried.

Virgin and Child mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Mother of God, container of the uncontainable

This mosaic of Christ faces a mosaic on the opposite wall, which pictures the Virgin with hands raised in prayer and the Christ child over her torso as if in her womb (view location in plan). The Virgin is labeled: “Mother of God, container (chora) of the uncontainable (achoritou).” This phrase, which describes the paradox that a human (Mary) could contain the Son of God (Jesus) in her womb, similarly references the monastery’s name. Such prominent images of Christ and the Virgin in the Chora reflect their important role in the Christian story of salvation, as well as the fact that the Chora monastery and parekklesion were likely dedicated to the Virgin and the main church to Christ.

Theodore Metochites and Christ mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Theodore Metochites and Christ mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Donor image

Proceeding into the inner narthex, viewers encounter a mosaic of the patron himself, Theodore Metochites, in the lunette over the door to the main part of the church, or naos (view location in plan). Christ sits on a jeweled throne against an expansive gold ground. Metochites kneels to Christ’s right, dressed in extravagant garments and wearing a flamboyant, turban-like hat, the asymmetry of the composition emphasizing the interaction between the two figures. This mosaic suggests Theodore’s high position within the empire but also his submission to Christ. As was common in medieval donation scenes, Metochites offers a model of the Chora—the very church in which this mosaic is located—to Christ.

Deësis

To the right, on the eastern wall of the inner narthex, a monumental Deësis mosaic shows the Virgin asking Christ to have mercy on the world (view location in plan). Because of her important role as the Mother of God, the Byzantines viewed the Virgin as a powerful intercessor between Christ and the faithful. John the Baptist, often included in the Deësis, has been omitted, probably to maximize the scale of the image within the space. Two past patrons of the Chora kneel on either side: Isaac Komnenos and a nun labeled “Melanie, the Lady of the Mongols,” who may be the daughter of emperor Michael VIII.

Deësis mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Chora and Hagia Sophia

For Byzantine viewers, the image of Theodore Metochites would have called to mind two imperial images in Constantinople’s great cathedral, Hagia Sophia. Metochites’ gesture of donation evokes the tenth-century mosaic of Constantine and Justinian offering models of the city and Hagia Sophia to the Virgin and Child in the southwest vestibule. And Metochites’ kneeling gesture and position above the central door to the naos echoes the tenth-century mosaic of the prostrating emperor above Hagia Sophia’s “Imperial Door.”

Left: Chora’s donor mosaic; top right: Hagia Sophia’s southwest vestibule mosaic; bottom right: Hagia Sophia’s Imperial Door mosaic (photos, byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA)

The large scale of the Chora’s Deësis alludes to the monumental Deësis mosaic installed in Hagia Sophia’s south gallery—a section of the church reserved for imperial use—following the Latin crusaders’ occupation of Constantinople from 1204–1261. These visual echoes, or “intervisuality” between the Chora and Hagia Sophia, suggest Metochites’ desire to associate himself with Byzantium’s emperors, and his church with the capital’s cathedral, Hagia Sophia. [2]

Left: Chora’s Deësis (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Hagia Sophia’s Deësis (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Christ and the Virgin

Christ and the Virgin are the main subjects of the majority of the mosaics that fill the inner and outer narthexes. Narrative scenes from the lives of the Virgin and Christ adorn various architectural spaces, and often exhibit experimentation with figures and compositions.

Annunciation mosaic, c. 1316–1321, inner narthex, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In a dynamic depiction of the Annunciation, the Virgin looks awkwardly over her shoulder as Gabriel approaches from above. The image responds to the triangular architectural surface in which it is situated, resulting in an unconventional, diagonal composition.

The Virgin with her parents, c. 1316–1321, inner narthex, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An image of the Virgin Mary with her parents exhibits a remarkable intimacy and evokes everyday life. Such “everyday” images in the Chora challenge common generalizations about Byzantine art as distant, spiritualized, and otherworldly.

South pumpkin dome, c. 1316–1321, inner narthex, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Detail of north pumpkin dome, c. 1316–1321, inner narthex, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The mosaics of the inner narthex culminate with two pumpkin domes (named for their fluted shape that resembles the undulating surface of a pumpkin) that display mosaics of Christ and the Virgin surrounded by their saintly ancestors from scripture (view location in plan).

Within the Chora, all human history seems to point toward these two figures and the pivotal role they play in the salvation of humankind.

The main church

Dormition mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: © thebyzantinelegacy)

Only three mosaics survive in the main church today. A mosaic of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary appears on the back (western) wall of the naos. And pair of proskynetaria icons of Christ and the Virgin once flanked the templon (the barrier between the sanctuary and naos, which no longer survives). These three images indicate that the emphasis on Christ and the Virgin that began in the narthexes continued in the main church where the Eucharist was celebrated.

Proskynetaria icons, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: © thebyzantinelegacy)

Chora church plan (adapted from plan © Robert G. Ousterhout)

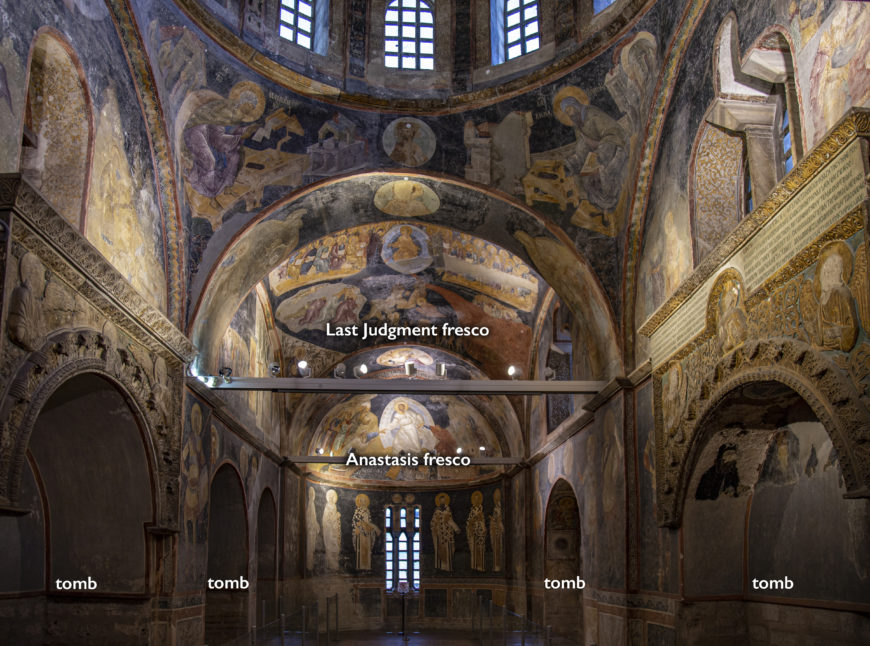

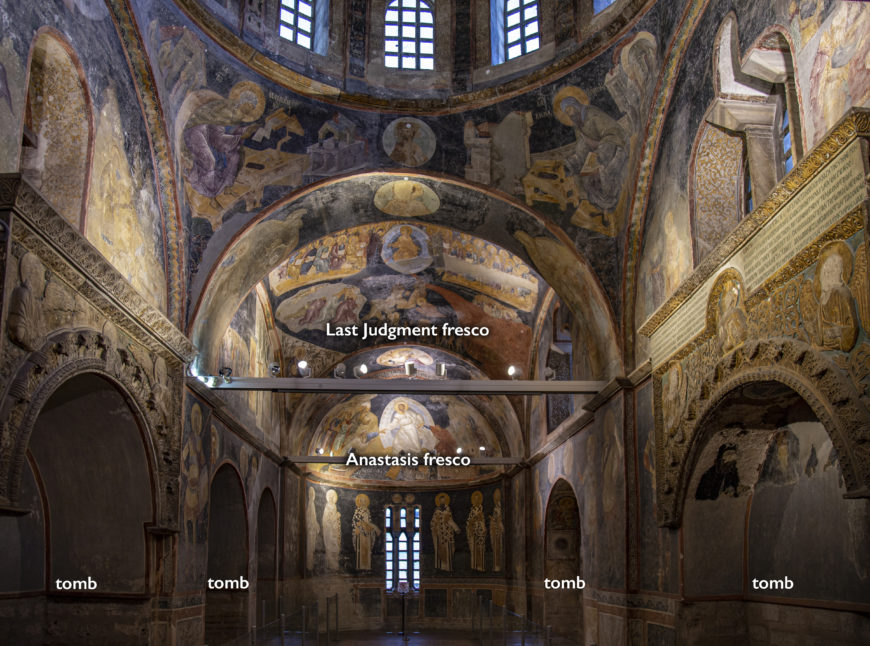

The Parekklesion

Better preserved are the frescoes in the parekklesion (side chapel), located to the south of the main church, which present a message of salvation that is fitting for this funeral chapel. Arcosolia (arched recesses for tombs) punctuate the walls and were intended for the burial of Metochites and his loved ones (view location of tombs in plan).

Parekklesion dome, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Warrior saint seem to guard the arcosolia, c. 1316–1321, parekklesion, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

One enters the parekklesion beneath a dome decorated with frescoes of the Virgin and Child surrounded by angels (view location in plan). Hymnographers appear in the pendentives beneath the dome. Further below are scenes from the Old Testament, including Jacob’s ladder, Jacob wrestling the angel, Moses and the burning bush, scenes with the Ark of the Covenant, and more, which were understood as “types” of Christ and the Virgin. In other words, the Byzantines believed these episodes from the Old Testament prefigured Christ’s salvation of humankind. At ground level, soldier saints surround the tombs, brandishing their weapons like sacred guardians over the dead.

Last Judgment fresco, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Judgment and Resurrection

Proceeding further into the parekklesion, the viewer passes under a sprawling image of the Last Judgment, sobering but also hopeful, since it depicts the damnation but also the salvation of souls (view location in plan). The parekklesion frescoes culminate at the east end with images of resurrection, reflecting the Christian belief that God will raise the dead at the end of time.

Anastasis fresco, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Parekklesion, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The focal point of the parekklesion is the Anastasis (“resurrection”) fresco in the apse (view location in plan). The voluminous garments on the figures in this scene are a hallmark of Late Byzantine art. Drawn from non-biblical texts, the Anastasis visualizes Christ descending into Hades (the underworld) following his crucifixion to free human souls from the captivity of death. Christ’s death on the cross has paradoxically made him a victor over death, as described in the Orthodox hymn for Pascha (Easter): “Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life!” Clad entirely in white, Christ strides dynamically over the broken locks and doors of the underworld, and a personification of Hades lies bound and defeated at the bottom of the composition. Adam and Eve—the archetypal first humans responsible for bringing sin and death into the world—are forcefully pulled from their tombs by the risen Christ.

Detail of Anastasis fresco, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Hope for salvation

Despite his considerable learning and political ambition, Metochites remained mindful of his mortality as he rebuilt the Chora monastery. While his donor image clearly communicated his position and achievements to all who entered the church, the frescoes of the parekklesion speak to Metochites’ anticipation of God’s judgment and his hope for resurrection and eternal life in the chora, or land, of the living.

[1] The Byzantines used a Greek version of the Hebrew Bible known as the Septuagint. This passage appears in the Septuagint Psalm 114:9.

[2] Robert S. Nelson, “The Chora and the Great Church: Intervisuality in Fourteenth-Century Constantinople,” Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 23 (1999): 67–101.

Cite this page as: Dr. Evan Freeman, “Picturing salvation — Chora’s brilliant Byzantine mosaics and frescoes,” in Smarthistory, April 28, 2021, accessed May 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/picturing-salvation/.