The breakdown of centralized control that characterized the First Intermediate Period brought a new sense of uncertainty to Egyptian culture, which had been so stable for centuries. The overlapping internal struggles between regional rulers in the north and south eventually ended with the Theban nomarchs defeating the rulers at Herakleopolis and bringing all of Egypt under a single king again.

The dynamic reunification of the Two Lands in ancient Egypt, in the period we call the Middle Kingdom, created new requirements for the king. No longer an aloof divine representative of the gods on earth, the king in the Middle Kingdom was expected to be more available to the people. This period also saw increased interactions with the outside world, the re-establishment of connections with Syria to the north and the establishment of forts reaching south deep into Nubia. Rich in literature (often of great knowledge and wit), this era also produced exquisite works of art. The cult of Osiris grew as did the number of Egyptians who could equip themselves for the afterlife, what we might recognize as a “middle class.”

Map of Ancient Egypt (modified) (original image: Jeff Dahl, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Middle Kingdom (c. 2030–1640 B.C.E.)

During the Middle Kingdom (Dynasty 11–13), many of the principles of Egyptian culture that had emerged at its outset and been codified during the Old Kingdom were adjusted and redefined. These included significant shifts in religious practices, afterlife beliefs, and the ideology of kingship.

Mortuary complex of Mentuhotep (with the later mortuary complex of Hatshepsut beside it), Deir El Bahari, Egypt (photo: Steve F-E-Cameron, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Nebhepetra Mentuhotep II re-unified Egypt and established the Middle Kingdom, which is often considered the classical period for Egypt’s politics, literature, and art. Although he ruled the unified country from the city of Memphis, as the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom had done, he built his innovative mortuary complex on the west side of the Nile at Thebes. He and his successors devoted considerable attention to the Theban region, adding to the already-established shrine of the local god Amun and building the initial core for the temple at Karnak (which would subsequently be added to by nearly every following ruler for millennia). There is evidence for vastly expanded royal patronage of divine temples all over Egypt during the Middle Kingdom. This campaign not only re-solidified the connections between the king and the gods, but was also a way to stress the king’s presence at key regional centers.

Twelfth Dynasty rulers focused their attention on restoring the glories of the Old Kingdom while accommodating the beliefs, innovations in style, and architectural forms that were introduced or developed at Thebes. These kings constructed a new royal residence in the Fayum region southwest of Memphis and were buried nearby in pyramids with elaborate temples. Unfortunately, due to the construction methods used and later stone mining, none survive in good condition. Unlike the solid limestone Old Kingdom pyramids, Middle Kingdom monuments of this type were built with a core of mud brick. After the outer casing stone was removed for reuse during the ancient and medieval eras, the brick cores were exposed, and have long since eroded.

Statue of Senwosret III (Senusret III), 1874–1855 B.C.E., 12th Dynasty, ancient Egypt, incised granite, found at the Temple of Mentuhotep, 122 cm high (© Trustees of the British Museum)

During the middle of the Twelfth Dynasty, a fascinating shift in the way pharaoh was portrayed occurred. In texts of the period, the role of the “Good Shepherd” becomes emphasized and, around the same time, the weight of royal responsibilities becomes evident in representations of the king. This dramatic shift in style is most clearly seen in the facial features of images of Senwosret II, Senwosret III, and Amenemhat III. Looking at these heavy faces, with their creased brows and drooping mouths, it is clear that profound changes had occurred.

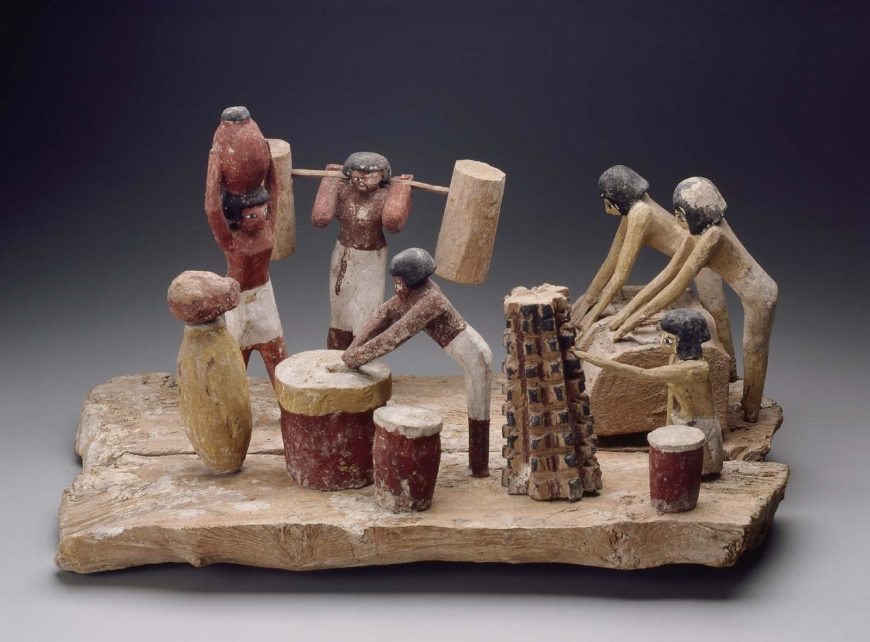

Model of a brewery, first Intermediate Period or Middle Kingdom, 2040–1991 B.C.E., painted wood, 28.5 x 32.5 x 53.5 cm (MFA Boston)

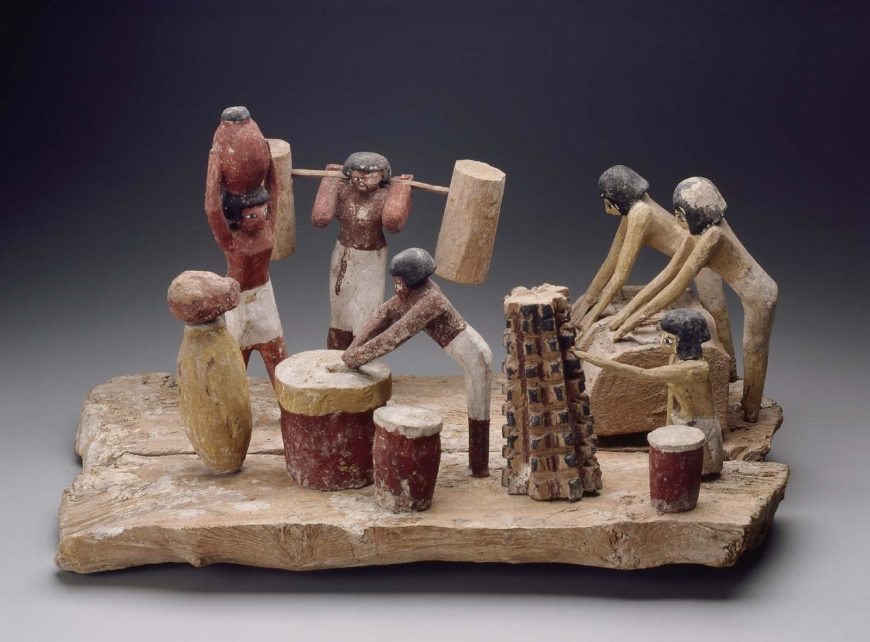

Elite necropolises carved into cliff sides along the Nile preserve non-royal aspects of the mortuary cult in this time. Much of the iconography in the tomb scenes is similar to late Old Kingdom, but new scenes also appear, including the representations of deities, especially the god Osiris. Models with figures in lively poses performing daily activities, like brewing, baking, and slaughtering cattle, were found in tombs of this era. Also during this period servant figures known as shabtis, which were designed to work for the deceased in the afterlife, began to appear. Private monuments dedicated to Osiris become prevalent and indicate a democratization of access to the divine, allowing more people the opportunity to interact with the gods.

Rectangular chest, cylinder seal, ingot, amulet, pendant, beetle, pearl, Treasure of Tod, dated to the reign of Noubkaoure Amenemhat II, materials: bronze, Egyptian alabaster, copper alloy, amethyst, silver, Egyptian blue, carnelian, rock crystal, copper, siliceous earthenware, jasper, lapis lazuli, mica, mother-of-pearl, obsidian, gold, bone, lead, flint, turquoise, glass, found under the temple of Montu at Tod (Louvre)

Rulers during the Middle Kingdom expanded control to the south into Nubia, building a series of mudbrick forts along the river as far south as Semna (below the Second Cataract) in order to better control the mines of gold and other valuable materials in the region, such as ebony, ostrich feathers, leopard skins, ivory, exotic animals, incense and a variety of hard stones. They also re-established trade routes to far-off Syrian cities for luxury goods such as cedar, wine, silver, and oil. There is evidence for robust trade interactions with other cultures as well: Minoan pottery sherds suggest trade with Crete and Asiatic artifacts, like large numbers of weights found in urban settings and the stunning assemblage of treasure discovered in four bronze chests under the temple of Montu at Tod, indicates connections beyond Syria-Palestine.

Pectoral and Necklace of Sithathoryunet with the Name of Senwosret II, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Senwosret II, c. 1887–1878 B.C.E., Egypt, Fayum Entrance Area, el-Lahun (Illahun, Kahun; Ptolemais Hormos), Tomb of Sithathoryunet (BSA Tomb 8), EES 1914, Gold, carnelian, feldspar, garnet, turquoise, lapis lazuli

This was a period of wealth and prosperity—a rich body of literature was produced, relief carvings of sublime beauty were created, bronze metalworking appears, and some of the most exceptional jewelry from the ancient world was crafted during this time. Several sets of highly-symbolic jewelry were discovered in the tombs of royal women. Imagery in the jewelry, statuary, and other depictions of royal women during this period show a strong connection between them and the goddess Hathor. Both the mother and wife of Horus in various myths, Hathor was also described as the mother, wife, or daughter of the sun god Ra—both male deities that the king was closely linked with. Royal women seem to have been viewed as mortal representatives of Hathor, serving a vital function in regeneration.

Head of a female sphinx, c. 1876–1842 B.C.E., Dynasty 12, Middle Kingdom, chlorite, 38.9 x 33.3 x 35.4 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Female sphinxes appeared during the Middle Kingdom, emphasizing a new connection between royal women in the fiercely protective role of the sun god’s daughter, the Eye of Ra. Although in general these developments in identity didn’t necessarily indicate significant changes in political status for royal women, it is interesting that the last king of the Twelfth Dynasty was the first known sole female ruler of Egypt, Nefrusobek.

By the Thirteenth Dynasty, centralized royal authority was again on the decline and control over Lower Egypt became more challenging. The ruling city of Lisht was abandoned and the kings reestablished the royal court and administrative seat in the southern city of Thebes. It would be nearly 150 years before a king would rule again over the united Two Lands.

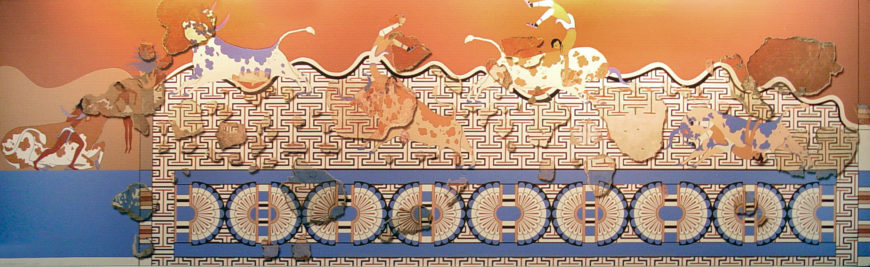

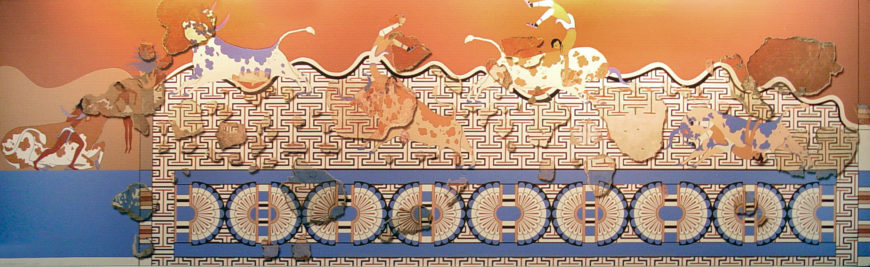

Reconstructed Minoan fresco showing bull-leaping from Avaris, Egypt. Now Archaeological Museum Iraklion, Crete, Greece (photo: Martin Dürrschnabel, CC-BY-SA-2.5)

Second Intermediate Period (c. 1640–1540 B.C.E.)

During the seventeenth century B.C.E., a group who originated in Western Asia and had blended into the local population of the delta region took control of the north of the country. Their kings were referred to as the hekau khasut, otherwise known as the Hyksos. These “rulers of foreign lands” established their own capital at Avaris and ruled the north, even calling themselves “Sons of Ra.” Archeological evidence shows that the community of Avaris had many decidedly non-Egyptian characteristics. Differences in house layouts, pottery types, weapons and tools, and burials being integrated into the settlement, as was common in western Asia, instead of separated (as was usual for the Egyptians), all point to a largely Syrio-Palestine population.

New words entered the Egyptian vocabulary during this period, as did Near Eastern deities, like Anat, and weapons including the scimitar and horse-drawn chariot. The international nature of the site is also evident in the startlingly Minoan-style murals of bull jumping, although these may date slightly later. Egyptian pharaohs still ruled from the south at Thebes, and there was a series of conflicts and battles for control. Textual evidence indicates that the king at Avaris was corresponding with the Nubian king of Kush at Kerma via the Western Oasis route in an effort to ally against the Egyptians at Thebes; their messengers were intercepted and communications cut off by the pharaoh Kamose who recorded his campaigns against them in stelae erected at Karnak temple. Eventually, Ahmose was successful in driving the Hyksos king out of the delta and re-unifying the land under a single ruler.

| Period |

Dates |

| Predynastic |

c. 5000–3000 B.C.E. |

| Early Dynastic |

c. 3000–2686 B.C.E. |

| Old Kingdom (the ‘pyramid age’) |

c. 2686–2150 B.C.E. |

| First Intermedia Period |

c. 2150–2030 B.C.E. |

| Middle Kingdom |

c. 2030–1640 B.C.E. |

| Second Intermediate Period

(Northern Delta region ruled by Asiatics) |

c. 1640–1540 B.C.E. |

| New Kingdom |

c. 1550–1070 B.C.E. |

| Third Intermediate Period |

c. 1070–713 B.C.E. |

| Late Period

(a series of rulers from foreign dynasties, including Nubian, Libyan, and Persian rulers) |

c. 713–332 B.C.E. |

| Ptolemaic Period

(ruled by Greco-Romans) |

c. 332–30 B.C.E. |

| Roman Period |

c. 30 B.C.E.–395 C.E. |

Additional resources:

Read an overview of Egyptian chronology and historical framework

Predynastic and Early Dynastic

Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period

New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period

Late Period and Ptolemaic and Roman Periods

Pylon gateway entrance to the temple complex of Amun-Re at Karnak, Egypt (photo: Mark Fox, CC: BY-NC 2.0)

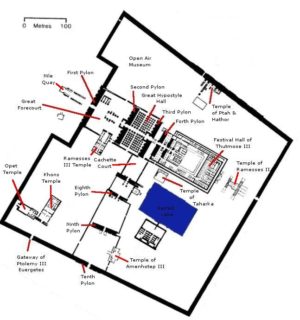

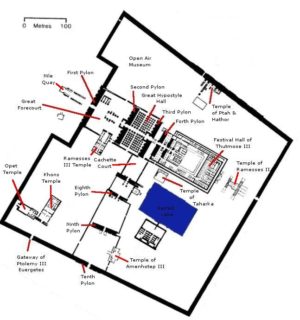

Plan, temple complex of Amun-Re, Karnak

The massive temple complex at Karnak was the principal religious center of the god Amun-Re during the New Kingdom in Egypt, and it can be overwhelming for modern visitors.

With its series of imposing pylon gateways and the towering forest of columns that forms the Great Hypostyle Hall, the complex is decidedly awe-inspiring yet daunting.

For more intimate interactions with ancient Egyptian sacred spaces, visitors can make their way to the area now referred to as the Open Air Museum, Karnak. Here, they can visit a series of small reconstructed chapels—one of them now known as the White Chapel, which preserves some of the most magnificent examples of relief carving from the ancient Mediterranean world.

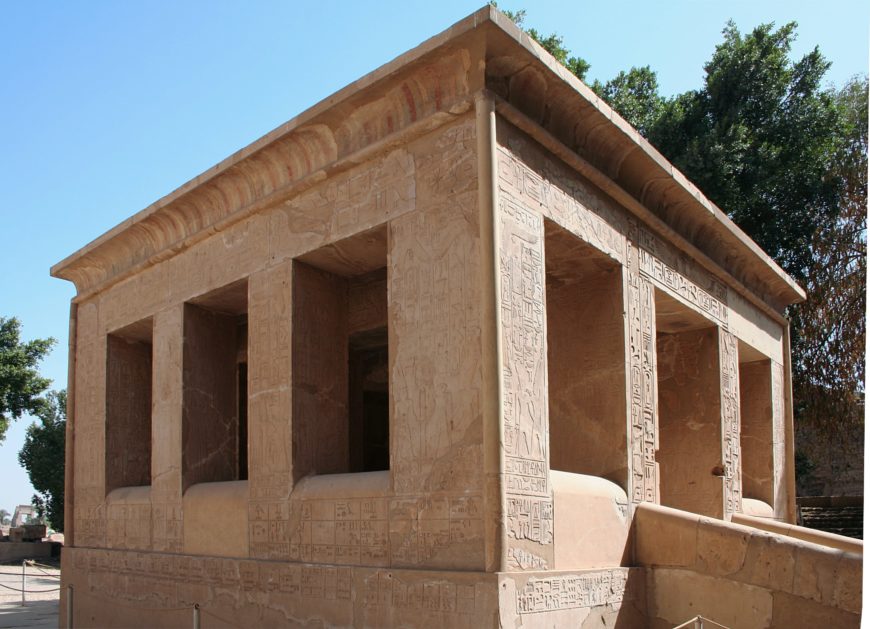

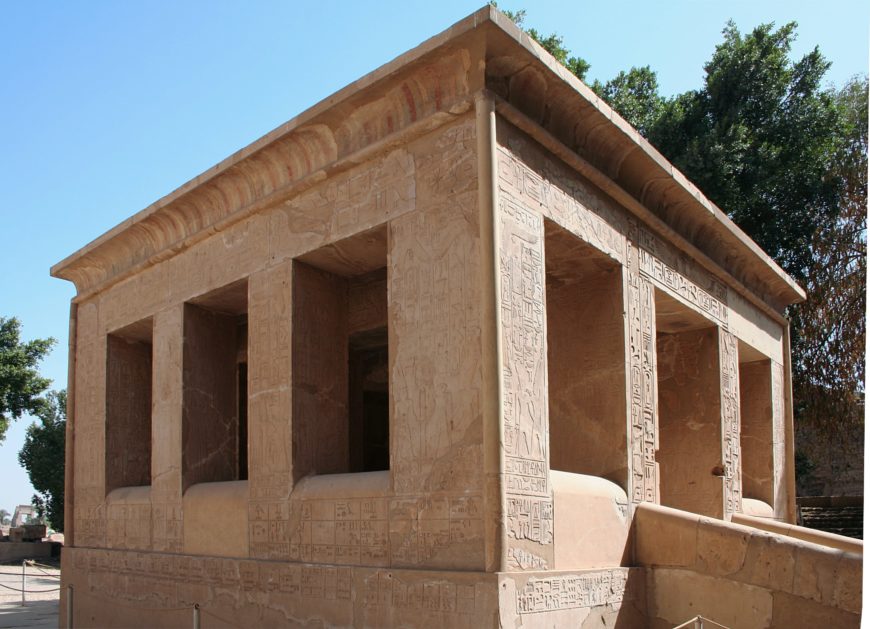

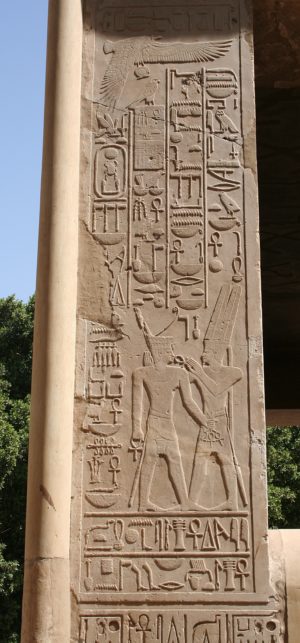

White Chapel, Karnak, c. 1971–1926 B.C.E. This elegant and delicately carved chapel was constructed by Senusret I, the second ruler of Dynasty 12, during the time referred to as the Middle Kingdom (c. 2030–1650 BCE). It is covered on nearly every surface with extraordinary relief scenes that were intended to rejuvenate the king and reaffirm his ability to rule (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

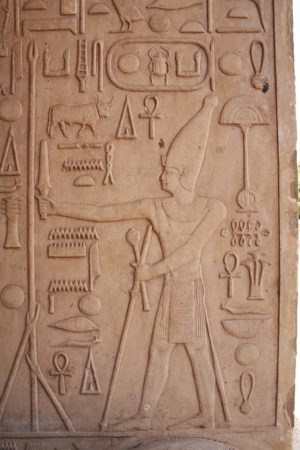

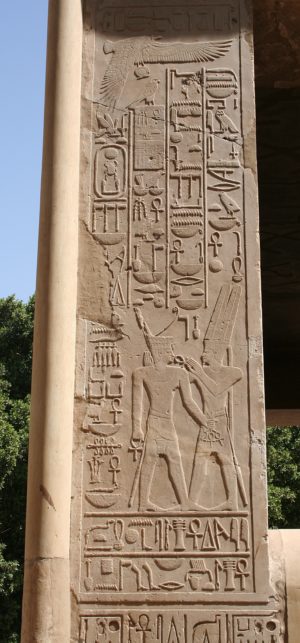

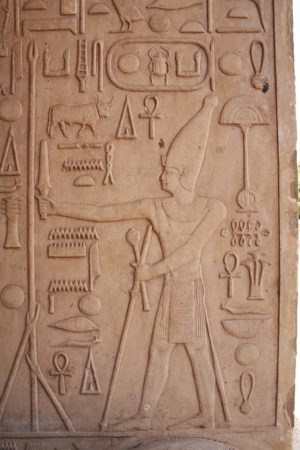

Senusret I performing a ritual action before Amun-Re on the White Chapel (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

The White Chapel

It is unknown exactly where the White Chapel originally stood, but it was likely outside the main enclosure wall of the temple complex to Amun-Re and oriented along a processional route. The chapel was created as the ceremonial kiosk for King Senusret I to sit enthroned during his rejuvenating heb-sed festival (a jubilee festival that occurred after a king had ruled for 30 years intended to show their continued strength and ability to govern). After Senusret’s death, the Chapel may have held a double statue of the king, perhaps intended to serve as a symbolic, “perpetual” festival kiosk.

Senusret I enjoyed a long, prosperous reign of approximately 45 years and invested in an extensive architectural program, building stone structures at nearly all existing cult sites and other established ritual locations/religious sanctuaries across Egypt. He specifically renovated prominent Old Kingdom sites—recognizing the importance of linking with the past. One goal in this extensive building program was to insure future centralized control (which had only recently been re-established by his predecessors during the First Intermediate Period).

One method Egyptian kings used to demonstrate this centralized control and stability was by maintaining a physical presence in cult locations throughout the country—they built structures to proclaim the king’s connections to the gods and their approval of his rule.

Senusret I was one of the earliest kings to build a major sanctuary for the God Amun-Re at Karnak. Amun-Re was rising in prominence during this time along with the region of Thebes (the family who reunited Egypt under a single ruler during the Middle Kingdom originated in this area). In addition, his choice to perform his heb-sed in this location was telling. By shifting the location away from the traditional political capital of Memphis. This action, moving this vital royal ritual down to Karnak, helped solidify the status of the Theban region that was becoming increasingly important during this time.

Senusret I also expanded control to the south, building and manning several fortresses along the Nile in Lower Nubia.

Between the outer pillars is a low balustrade with a rounded top. Traces of paint—including yellow, blue, red, and white—survive on the cornice, so the White Chapel was also painted in addition to being thoroughly covered in relief. White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak, c.1971–1926 B.C.E. (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Somewhere in the forecourt of his Amun temple, Senusret erected the small limestone shrine named the “Throne of Horus,” which is now referred to as the White Chapel. This marvelous chapel is nearly square in floor plan and set on a high base with stepped ramps on two sides, and includes a total of sixteen pillars. The roof is topped with an elegantly curved cavetto cornice and enhanced with decorative water spouts.

View of one side of the White Chapel, showing the curved cornice and decorative water spout. White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak, c.1971–1926 B.C.E. (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

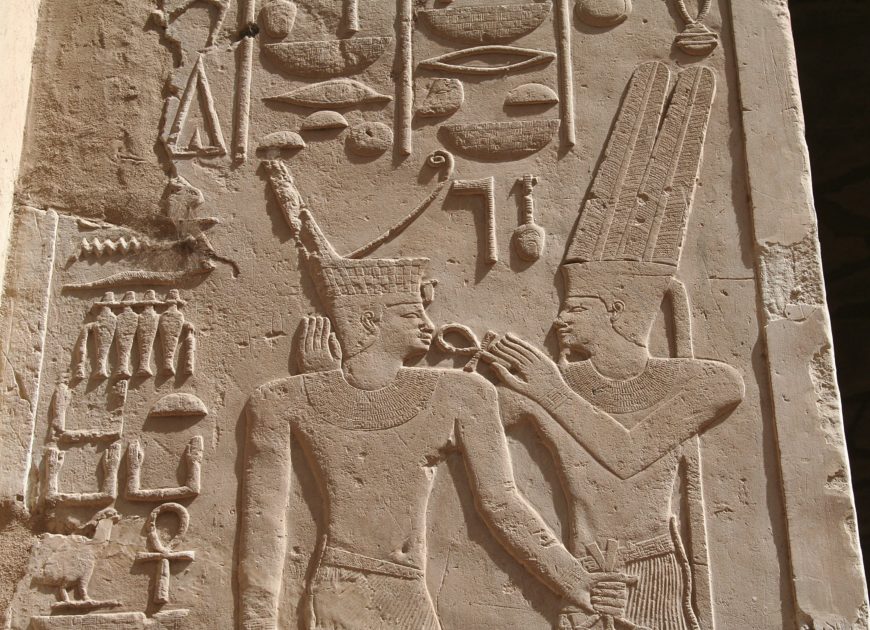

Corner pillar of the White Chapel showing Senusret I being presented with the “breath of life” by Amun-Re.

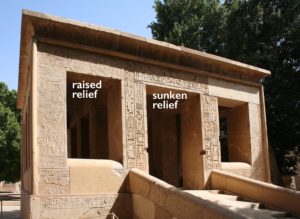

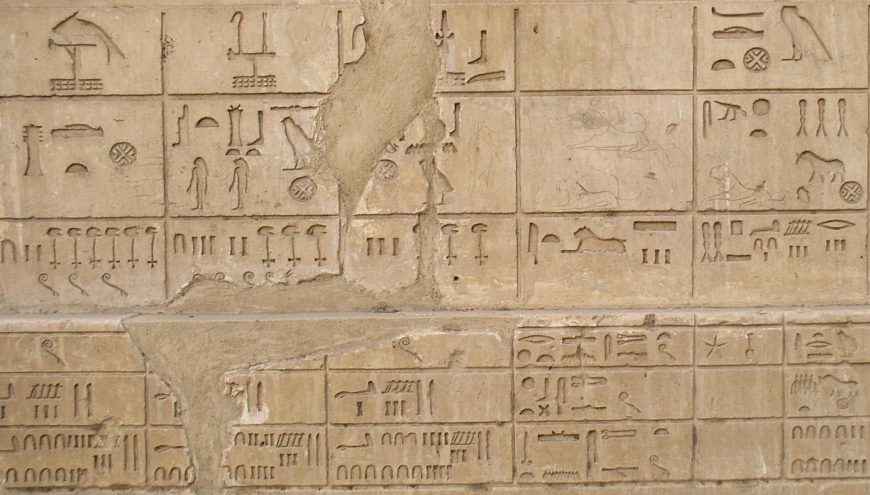

The exceptional decoration on the pillars records the heb-sed jubilee festival of Senusret I in raised relief. Each pillar is carved on all four sides with long vertical columns of hieroglyphs above a scene of the king (Senusret I) ritually interacting with a deity over two horizontal lines of text referring to the “first occasion of the heb-sed.” The God Amun-Re is most often depicted, with seven different forms of that deity represented, but other gods like Re-Horakhty, Anubis, Thoth, Horus, and Ptah are also present.

The iconography of these scenes is rich and elaborate, with incredibly minute carving and extremely detailed renderings of the imagery. The high quality of the reliefs is mirrored in other royal monuments of the time, suggesting that there may have been a unifying style that dominated this period.

Detail of above pillar scene showing the unusual incised details of the king’s crown. White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak, c.1971–1926 B.C.E. (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

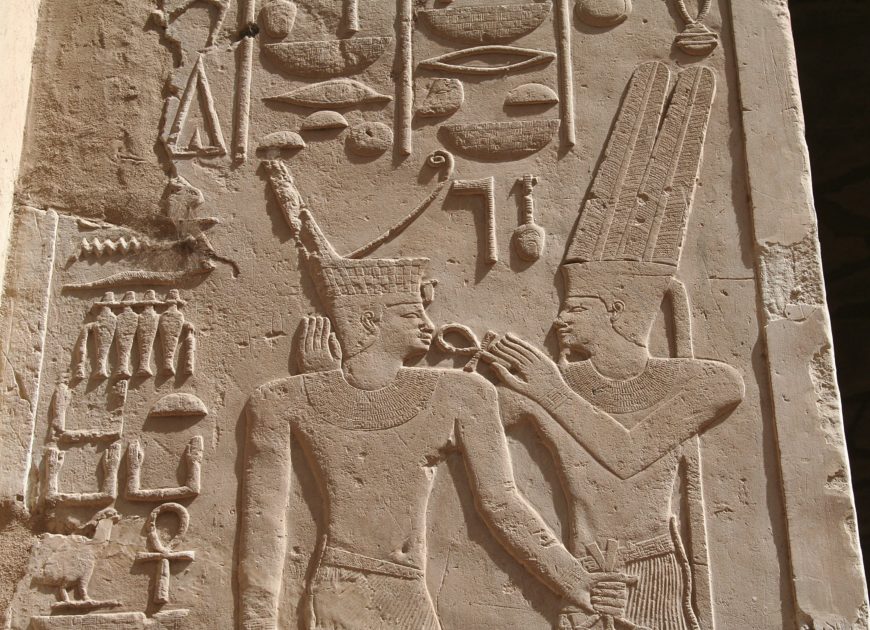

Carvings on the White Chapel

Detail of Amun’s feathered costume on the White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak, c.1971–1926 B.C.E. (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

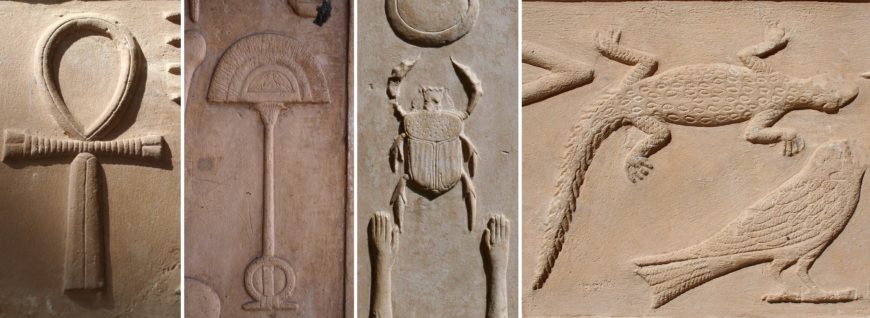

Relief on the White Chapel goes beyond the usual, however, and even tiny interior elements of the hieroglyphs, including all the small details of things like feathers, crowns, and jewelry, were actually carved into the stone. Typically these details were only shown in the paint and it is rare to find these details in the carving as well.

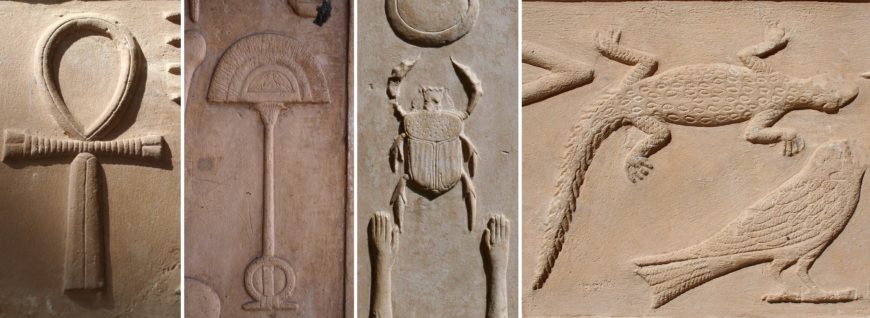

The hieroglyphs carved on the White Chapel are executed with such intricacy that we can discern each scale on the snakes and each feather on the birds. The details are utterly fascinating and telling: the enigmatic ankh symbol reveals itself to be a specially wrapped cloth; every element of this fan, including the scene carved on its central section, is carefully depicted. A scarab beetle is exceptional in its specificity; the scales of a lizard are delicately delineated.

Ankh symbol, fan, scarab beetle and lizard, White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak, c.1971–1926 B.C.E. (photos: Dr. Amy Calvert)

White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak, c.1971–1926 B.C.E. (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

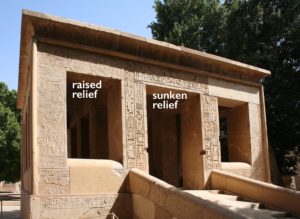

The exterior scenes on the base of the White Chapel and framing the two doorways were carved in sunk relief.

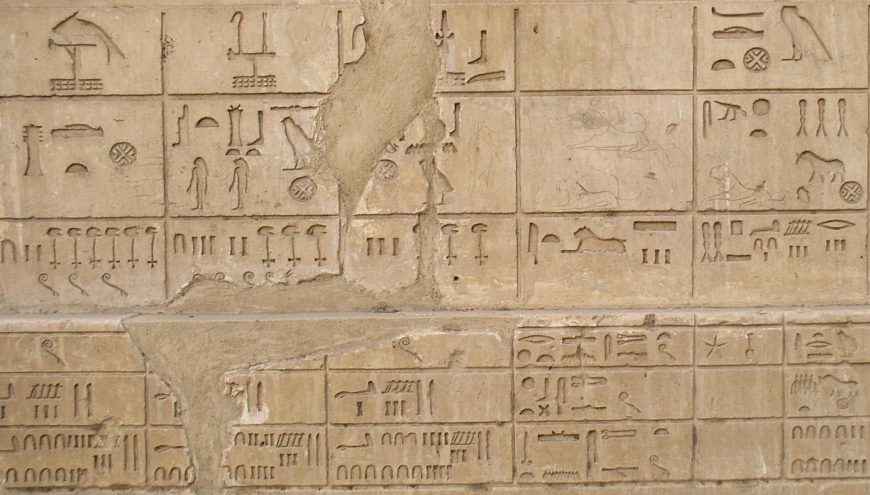

The scenes on the base are of particular interest as they refer to an important survey of Egypt’s main features and locations that was carried out by Senusret I. The base includes depictions of different personifications of natural features, like the Nile, and other important chapels. Two of the sides list the contemporary nomes (geographic designations, similar to modern provinces)—twenty-two in Upper Egypt on the south side and fourteen in Lower Egypt on the north—and show their measurements.

Detail of the survey record of Egyptian nomes, showing several of their names and measurements. Base of the White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak, c.1971–1926 B.C.E. (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

The White Chapel after Senusret I

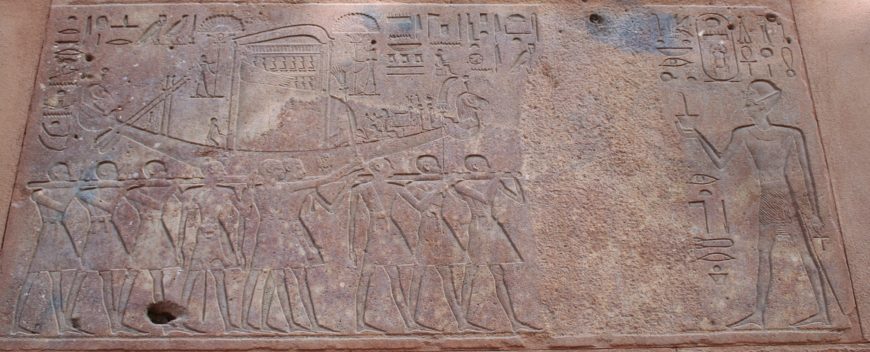

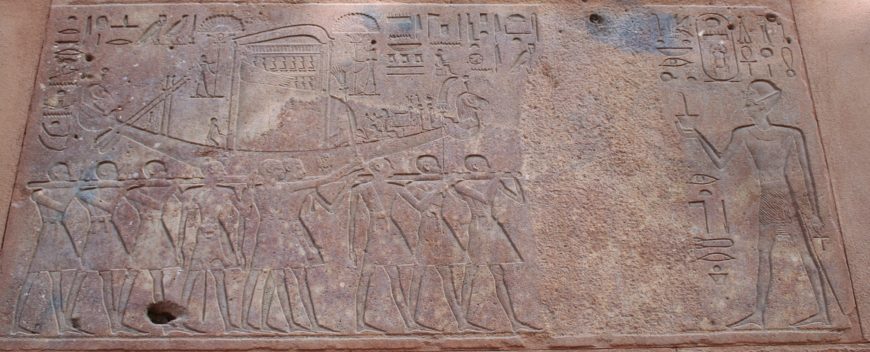

Later kings converted the chapel into a bark shrine (a ritually pure location where a god’s divine bark (ship) could be set down during festival parades so the priests could rest—a necessary fixture along processional routes). One of the major features of many ancient Egyptian festivals were processions of small sculptures of divine figures. These usually stayed in the innermost sanctuary of the temple, where they received daily ritual actions. On festival days they emerged from the temple, generally carried in a boat-shaped palanquin by pairs of priests, and “visited” each other at their respective temples, which gave the populace an opportunity to view and interact with their deities.

Scene of a bark procession, showing the divine bark of Amun being offered incense by kings Hatshepsut (later removed) and Thutmosis III. White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak, c.1971–1926 B.C.E. (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

The White Chapel was dismantled during the early Eighteenth Dynasty and the blocks were included in the foundation of the massive Third Pylon that now forms the back wall of the (later) Great Hypostyle Hall. In 1924, the repair of the Third Pylon was undertaken. During this work, around 950 blocks from a total of eleven different structures were found used as fill within the pylon. While some blocks had been damaged, many preserved astonishingly beautiful relief carving. The White Chapel was carefully reconstructed and now stands in the Open Air Museum at Karnak along with other, similarly reconstructed shrines.

Additional resources

The world of ancient Egypt, a Reframing Art History chapter.

Ancient Egyptian religious life and afterlife, a Reframing Art History chapter.

Video of the re-opening of the processional route between Karnak and Luxor, complete with full barque procession.

Statue of Senwosret III (Senusret III), 1874–1855 B.C.E., 12th Dynasty, ancient Egypt, incised granite (granodiorite), found at the Temple of Mentuhotep, South Sourt, Deir el-Bahari, 122 cm high (© Trustees of the British Museum)

This life-size statue of Senwosret III (1874–1855 B.C.E.) is one of three very similar statues in the British Museum collections excavated from the site of the funerary temple of King Nebhhepetre Mentuhotep II (2055–2004 B.C.E.), a predecessor of Senwosret. Senwosret restored and endowed this temple, which was the site of an important local annual festival. It is likely that the statues were dedicated out of respect for the earlier king and the festival.

Statue of Senwosret III (Senusret III), c. 1850 B.C.E., 12th Dynasty, ancient Egypt, incised granite (granodiorite), found at the Temple of Mentuhotep, South Sourt, Deir el-Bahari, 122 cm high (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The statues, which show Senwosret in the attitude of prayer, standing with his hands flat on the front of his kilt, are the earliest examples of this devotional pose. In contrast with his youthful, muscular torso, the king’s face is depicted with expressive furrows and lines. His large ears may symbolize the ruler’s readiness to listen. This new style of representation, so different from the idealized portrayals of royalty in other periods, is characteristic of this reign.

Statue of Senwosret III (Senusret III), c. 1850 B.C.E., 12th Dynasty, ancient Egypt, incised granite (granodiorite), found at the Temple of Mentuhotep, South Sourt, Deir el-Bahari, 122 cm high (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Contemporary poetry spoke of how the heaviest burden, that of rulership, lay on the king, and this powerfully modeled portrait seems to reflect that. The expressiveness of the portrait is royal rather than personal. One Egyptologist, T.G.H James, has described it as a “portrait of responsible kingship.”

© Trustees of the British Museum