Neo-Babylonia

Neo-Babylonia

The Neo-Babylonian Empire developed an artistic style motivated by their ancient Mesopotamian heritage.

Key Points:

- The Neo-Babylonian Empire was a civilization in Mesopotamia between 626 BCE and 539 BCE. During the preceding three centuries, Babylonia had been ruled by the Akkadians and Assyrians, but threw off the yoke of external domination after the death of the last strong Assyrian ruler.

- Neo-Babylonian art and architecture reached its zenith under King Nebuchadnezzar II, who ruled from 604–562 BC. He was a great patron of art and urban development and rebuilt the city of Babylon to reflect its ancient glory.

- Most of the evidence for Neo-Babylonian art and architecture is literary. Of the material evidence that survives, the most important fragments are from the Ishtar Gate of Babylon.

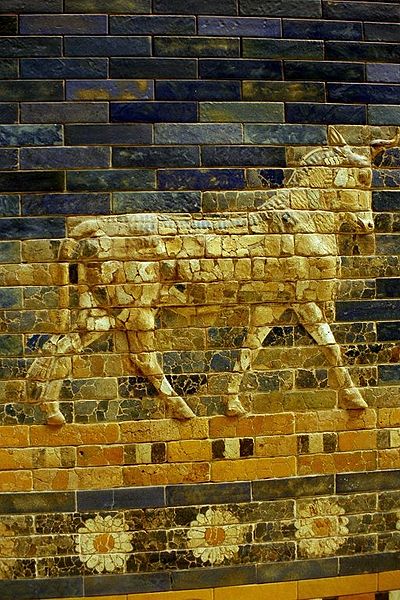

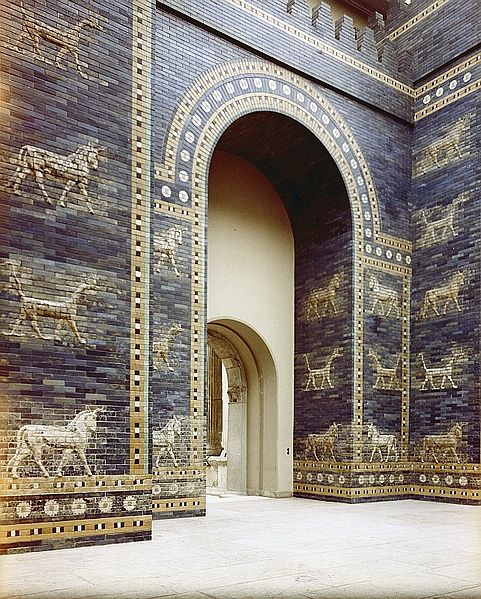

- Neo-Babylonians were known for their colorful glazed bricks, which they shaped into bas-reliefs of dragons, lions, and aurochs to decorate the Ishtar Gate.

Key Terms

- glazed:Having a vitreous coating whose primary purposes are decoration or protection.

- aurochs:An extinct European mammal, Bos primigenius, the ancestor of domestic cattle.

- ziggurat:A temple tower of the ancient Mesopotamian valley, having the form of a terraced pyramid of successively receding stories

The Neo-Babylonian Empire, also known as the Chaldean Empire, was a civilization in Mesopotamia that began in 626 BC and ended in 539 BC.

During the preceding three centuries, Babylonia had been ruled by the Akkadians and Assyrians, but threw off the yoke of external domination after the death of Assurbanipal, the last strong Assyrian ruler. The Neo-Babylonian period was a renaissance that witnessed a great flourishing of art, architecture, and science.

The Neo-Babylonian rulers were motivated by the antiquity of their heritage and followed a traditionalist cultural policy, based on the ancient Sumero-Akkadian culture . Ancient artworks from the Old-Babylonian period were painstakingly restored and preserved, and treated with a respect verging on religious reverence. Neo-Babylonian art and architecture reached its zenith under King Nebuchadnezzar II, who ruled from 604–562 BC and was a great patron of urban development, bent on rebuilding all of Babylonia’s cities to reflect their former glory.

It was Nebuchadnezzar II’s vision and sponsorship that turned Babylon into the immense and beautiful city of legend. The city spread over three square miles, surrounded by moats and ringed by a double circuit of walls. The river Euphrates, which flowed through the city, was spanned by a beautiful stone bridge. At the heart of the city lay the zigguratEtemenanki, literally “temple of the foundation of heaven and earth.” Originally seven stories high, it is believed to have provided the inspiration for the biblical story of the Tower of Babel.

It was also during this period that Nebuchadnezzar supposedly built the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, although there is no definitive archeological evidence to establish their precise location. Ancient Greek and Roman writers describe the gardens in vivid detail. However, the lack of physical ruins have led many experts to speculate whether the Hanging Gardens existed at all. If this is the case, writers might have been describing ideal mythologized Eastern gardens or a famous garden built by the Assyrian king Sennacherib (704–681 BCE) at Nineveh roughly a century earlier. If the Hanging Gardens did exist, they were likely destroyed around the first century CE.

19th-century reconstruction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon: Two lamassu sculptures in the round face each other in the foreground, while another reconstruction of the ziggurat Etemenanki dominates the background.

Most of the evidence for Neo-Babylonian art and architecture is literary. The material evidence itself is mostly fragmentary. Some of the most important fragments that survive are from the Ishtar Gate, the eighth gate to the inner city of Babylon. It was constructed in 575 BC by order of Nebuchadnezzar II, using glazed brick with alternating rows of bas-relief dragons and aurochs. Dedicated to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar, it was a double gate, and its roofs and doors were made of cedar, according to the dedication plaque. Babylon’s Processional Way, which was lined with brilliantly colorful glazed brick walls decorated with lions, ran through the middle of the gate. Statues of the Babylonian gods were paraded through the gate and down the Processional Way during New Year’s celebrations.

Ishtar Gate detail: An aurochs above a flower ribbon with missing tiles filled in (Ishtar Gate bas-relief, housed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin). A prominent characteristic of Neo-Babylonian art and architecture was the use of brilliantly colorful glazed bricks.

The reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate and Processional Way, built at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin in 1930, features material excavated from the original site. To compensate for missing pieces, museum staff created new bricks in a specially designed kiln that was able to match the original color and finish. Other parts of the gate, which include glazed brick lions and dragons, are housed in different museums around the world.

Ishtar Gate at Pergamon Museum: This was reconstructed in Berlin in 1930, using materials excavated from the original build-site.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Hanging_Gardens_of_Babylon.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: upload.wikimedia.org/Wikipedia/commons/a/ae/Hanging_Gardens_of_Babylon.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ish-tar Gate detail. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ish-tar_Gate_detail.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Fotothek df ps 0002470 Innenru00e4ume ^ Ausstellungsgebu00e4ude. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fotothek_df_ps_0002470_Innenr%C3%A4ume_%5E_Ausstellungsgeb%C3%A4ude.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Neo-Babylonian Empire. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Neo-Babylonian_Empire. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanging_Gardens_of_Babylon. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- aurochs. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/aurochs. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ishtar Gate. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishtar_Gate. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com//art-history/definition/glazed. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- ziggurat. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/ziggurat. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike