Norman Art and Architecture

Art of Conquest

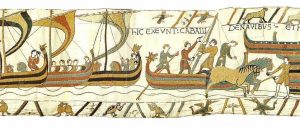

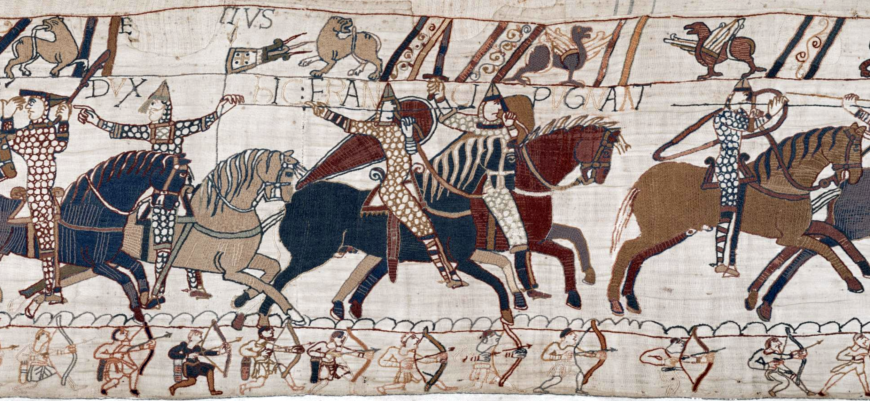

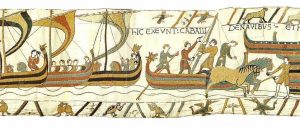

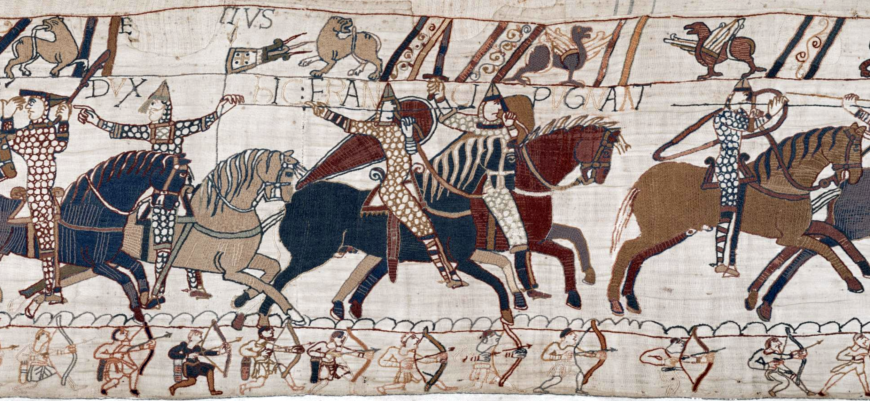

Horses disembarking from Norman longships, Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

The invasion

On September 28, 1066, the tiny community of Pevensey (on the south-east coast of England), huddled inside the ruins of a late Roman fortification. They would soon be overwhelmed with the arrival of William, Duke of Normandy, and an army intent on invasion. Thousands of invaders had crossed the English Channel from Normandy on hundreds of open longships that were big enough to carry cavalry horses and the supplies needed to lay siege to the coastal cities guarding England.

Map showing the coasts of Normandy (in present-day France) and the location of the Battle of Hastings, in England

William had been preparing for the invasion since the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, Edward the Confessor, had died without a direct heir months earlier.

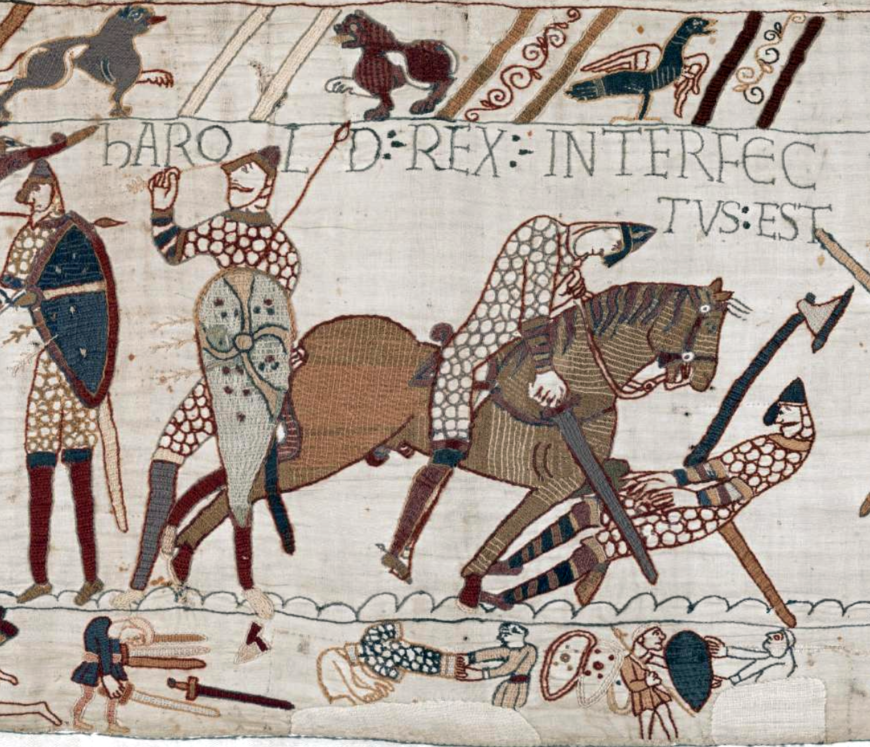

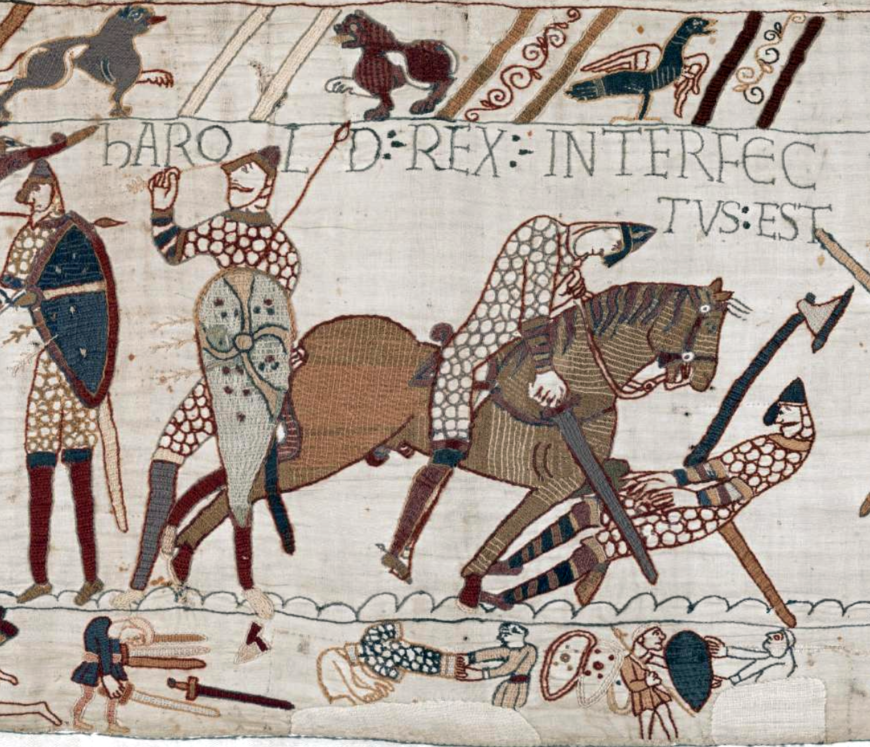

Edward had been succeeded by a newly appointed ruler, Harold Godwinson, but both William and the King of Norway, Harold Hardrada, also laid claim to the throne. Harold Hardrada had crossed the North Sea to invade near present-day Newcastle in the north of England, arriving at almost exactly the same time as William’s army made land further south. Forced to defend two coasts almost three hundred miles apart in quick succession, Harold Godwinson succeeded in defeating the king of Norway, but fell on the field at the Battle of Hastings, just up the coast from Pevensey, shot through the eye with an arrow. Harold’s sizeable army was no match for the mounted warriors William had brought from Normandy. His forces quickly marched west, to Dover and Canterbury, then east, leaving devastation in their wake. By Christmas, 1066, William the Conqueror had been crowned king of England, but facing a rebellion, he continued to lay waste to a huge swath of the country before he had all of England firmly within his grasp.

The death of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

Weaving a Norman tale

The works of art and architecture made in the wake of this invasion testify to the power of art as a tool for colonization. Perhaps the most famous of these is the Bayeux Tapestry. Within twenty years of the Norman Conquest of England, needle-workers embroidered dozens of scenes describing the invasion onto this 230-foot-long linen strip using wool and linen yarn. Between narrow upper and lower borders populated by animals, people and objects that act as a subtle commentary on the central narrative, a history of the Norman Conquest unscrolls from left to right, ending abruptly with a tattered, incomplete scene of mace-wielding Anglo-Saxon foot soldiers fleeing the victorious Normans. Embroidered Latin titles help to identify people, places and events.

Wounded soldiers and horses (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

Scholars have never pinned down where or by whom the embroidery was carried out, or where it was meant to be displayed—a mystery compounded by the fact that this is the only storytelling textile strip of this sort preserved from the Middle Ages. In it, William is portrayed ordering his men to build a fleet of longships, stock them with arms and armor, food, wine, and horses, and set sail for England, where they feast, plan, and finally attack. The ensuing slaughter is unflinchingly rendered: in the lower border, dismembered bodies are stripped by battlefield looters. The style of the tapestry, with its gangly-limbed, beaky-nosed figures, agitated gestures, stolid drapery folds, abrupt changes in scale, and multicolored trees made of rubbery, interlaced fronds, has similarities to other works found on both sides of the Channel. Anglo-Saxon England and the Duchy of Normandy had been exchanging artwork, artists, clergy, and nobles well before the Conquest (their rulers were closely related—King Edward the Confessor’s mother, Emma of Normandy, was William the Conqueror’s great aunt).

Normans first meal in England, at the center is Bishop Odo, who gazes out as he offers a blessing over the cup in his hand (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

If we can’t use style to judge where the tapestry was made, we can instead turn to the story, which displays an indisputably Norman bias, to identify its intended audience. Many medieval texts retold the events of the invasion from both the Anglo-Saxon and Norman perspectives, but Bishop Odo of Bayeux, William’s half brother, figures prominently in the Bayeux tapestry, where he is shown blessing a feast on the eve of battle, advising William, and rallying the troops. It is likely, then, that Odo commissioned the tapestry to celebrate his brother’s victory, and the tale that unfolds along its length highlights William’s (and Odo’s) valor and the supposed wrongdoings of Harold Godwinson, who is depicted swearing an oath to be William’s vassal, but then allowing himself to be crowned King of England. The tapestry completely ignores Harold’s victory over the Norwegian king, instead focusing on events of interest to Normans.

Preparations for war, including the building of a motte-and-bailey (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

Motte-and-bailey castles

While the tapestry’s renditions of ships, weapons, horses, feasts and buildings have been mined by historians for information about daily life and military campaigns, many details are doubtless the result of artistic license. Still, the tapestry showcases some important Norman innovations. After the feast presided over by Bishop Odo, the invaders are shown shoveling dirt onto a striped mound crowned by a structure labeled “Hesteng ceastra“ (above). This is the castle of Hastings, one of several such castles (including one at Dover, discussed below, as well as the Tower of London) that William had built during and after his invasion. With these, he imported into England a type of defensive structure that was typical in Normandy and became essential for establishing control over his new English subjects.

The simplest of Norman castles comprised a mound, or motte, of alternating layers of earth and stones, topped with a wooden palisade and an enclosed residence, or keep, and surrounded by a ditch. Either surrounding this or contiguous with it was an open yard, or bailey, ringed with a wooden defensive barrier. Such defenses could be thrown up quickly and made use of existing land features. They provided security for the soldiers, horses, and equipment necessary to subdue the surrounding inhabitants, a vantage point from which to observe potential foes, and a looming presence to intimidate them.

Model of a motte-and-bailey (Carisbrooke Castle, 14th century, England) (photo: Charles D. P. Miller)

Lacking a standing professional army that could defend the walls of a city, medieval rulers like William appointed nobles to subdue parcels of the countryside in return for land and goods. If a castle’s location proved to be advantageous in the long term, the wooden structure on top was replaced with a masonry keep that provided permanent and more comfortable housing for the governing lord and his family. Round, rectangular, or faceted, these could be hollow shell keeps with buildings clustered against an exterior wall, or solid great towers, like the keep at Dover (below).

Aeriel view of Dover Castle, 12th century (Kent, England) (photo: Lieven Smits)

Topping these structures one often sees crenellations, which allowed archers to defend the perimeter while sheltering behind a stone wall. At Dover, as was typical, the wooden palisade surrounding the bailey was over time replaced by multiple concentric stone walls, a moat, and a barbican (an outer fortified gate).

With its towering presence, the motte-and-bailey castle combined the practical functions necessary to govern a rural population or the inhabitants of a conquered city with the symbolism of domination.

Durham Cathedral on the River Wear, Norman construction founded 1093 (Durham, England) (photo: Domstu)

A Norman cathedral

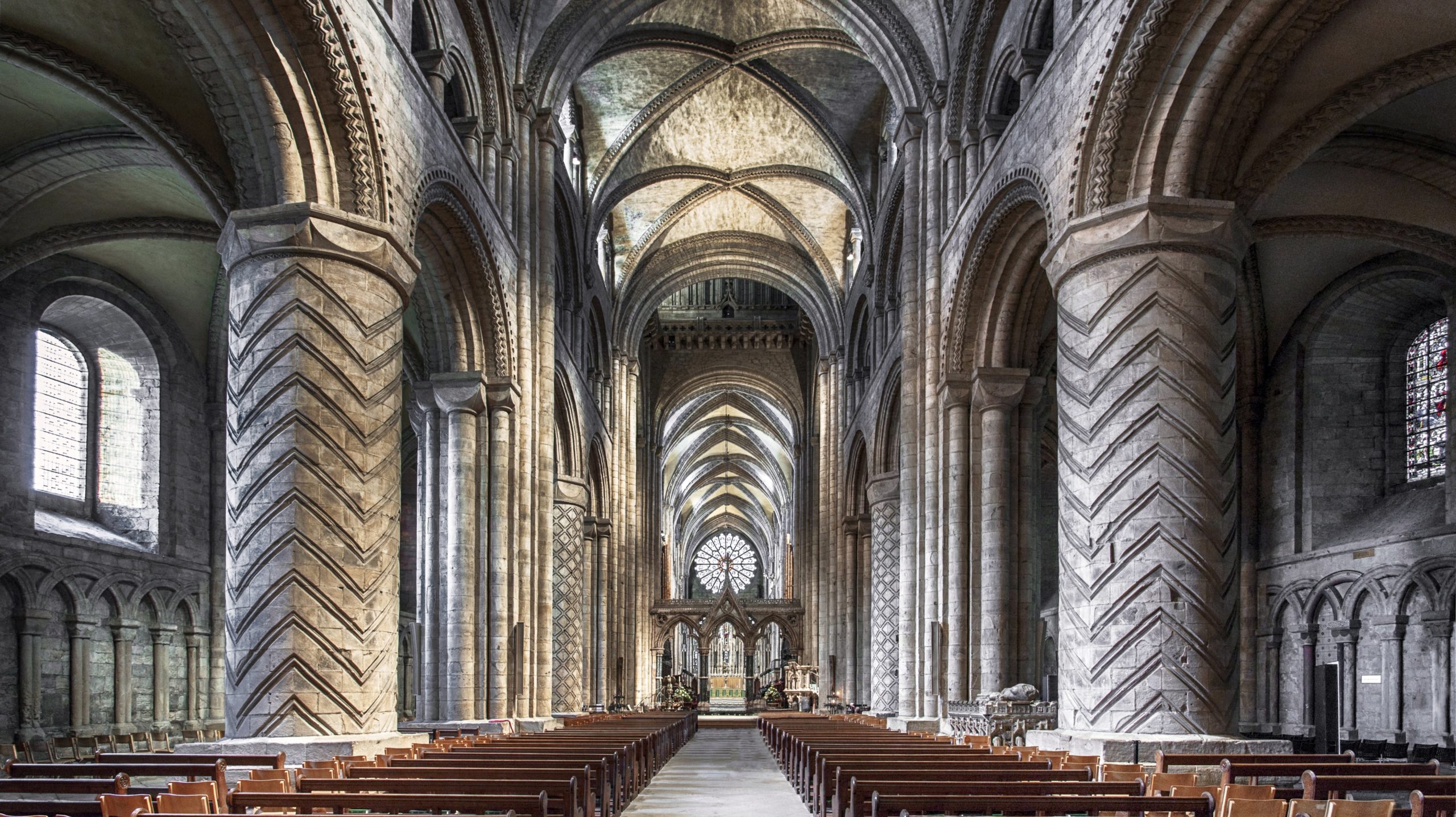

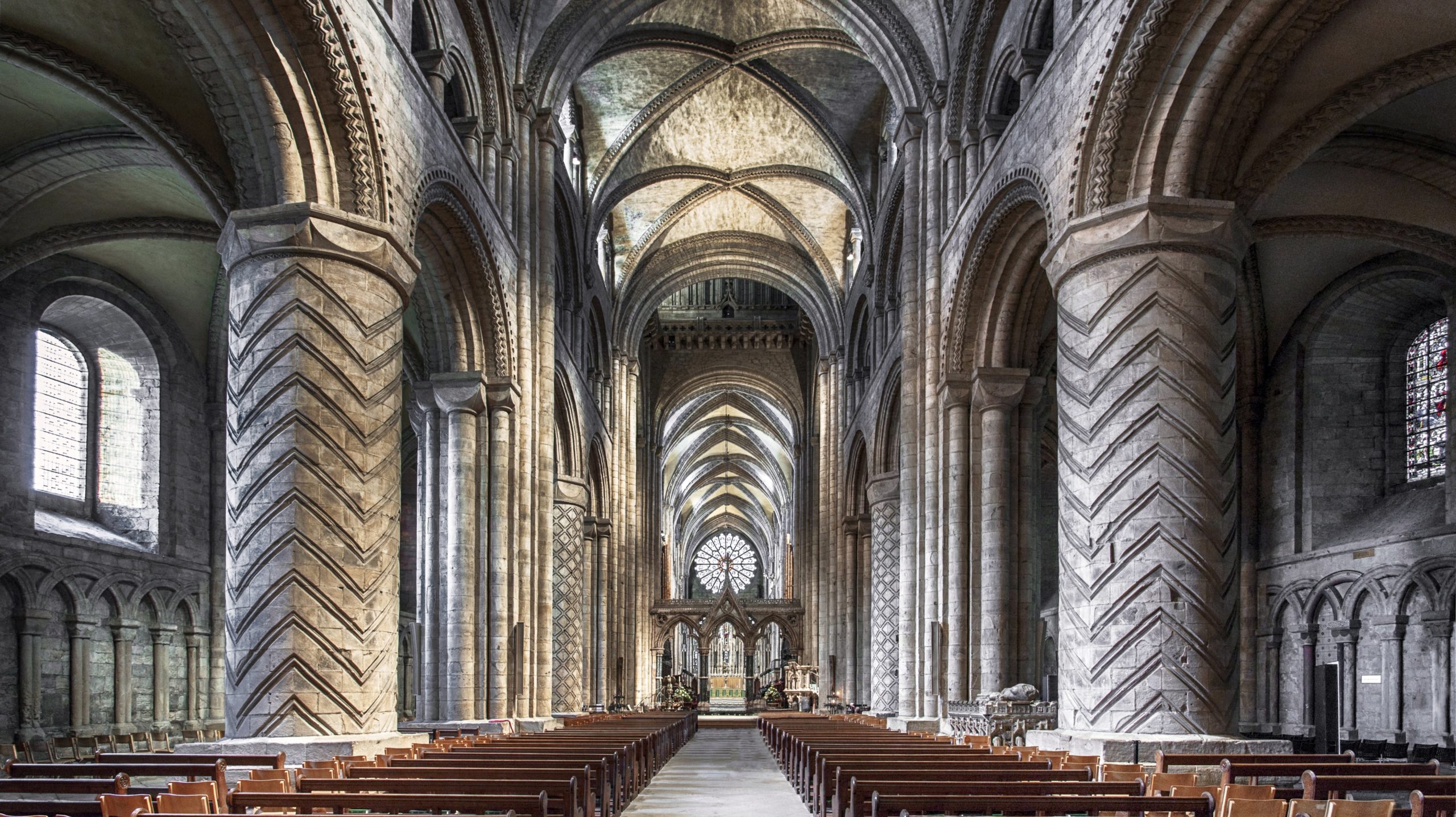

William the Conqueror had first visited Durham Cathedral—then an Anglo-Saxon stone church—on its peninsula in a bend of the River Wear (above) on his first northern campaign. Durham Cathedral was an important touchstone of Anglo-Saxon national identity, holding the relics of Cuthbert, their patron saint. Recognizing its strategic importance, William fortified one end of the site with a motte-and-bailey castle, and invited another Norman, William of Saint-Calais (who then became Bishop William), to take over the venerable cathedral and remake it in the image of a Norman church. Bishop William expelled the clergy he found there and replaced them with Benedictine monks. By 1093, he had begun construction on the largest and most technically innovative Norman church of its time.

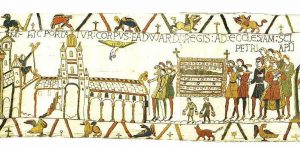

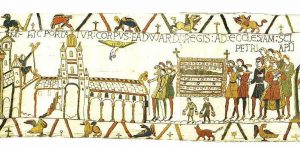

Edward the Confessor’s body being carried into Westminster Abbey, Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

The Anglo-Saxons were already familiar with some Norman building practices and styles. In the Bayeux Tapestry, we see Edward the Confessor’s body carried to Westminster Abbey, which had been dedicated just days before his death. The church is depicted as a substantial structure with arcades (here, rows of columns topped with arches), clerestory windows, a transept and multiple towers. Edward had built it to be his own burial church, and excavations show that it probably resembled a Norman abbey near where Edward had spent much of his youth. At the time, observers described Westminster Abbey’s style as new and unusual. In the wake of the Conquest, however, major English churches were built or rebuilt only in this style rather than in the then prevalent Anglo-Saxon style, marking Norman control of the Church in starkly visual terms.

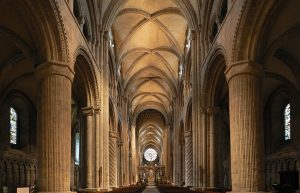

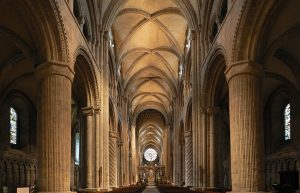

William the Conqueror and his wife, Matilda, had already commissioned impressive church buildings in their Norman capital city, Caen, that showcased the key characteristics of the Norman style. We can also see these at Durham, begun after William’s death but still part of the legacy of his invasion. A façade with two monumental towers looms over the fortifications and the steep banks of the Wear surrounding Durham’s peninsula. Behind this façade, a broad nave is separated from aisles by massive arches framed with complex decorative stone moldings, sitting on gigantic alternating piers.

Interior of Durham Cathedral, Norman construction founded 1093 (Durham, England) (photo: Oliver-Bonjoch)

Heavy stone, cleverly disguised

The clerestory windows of the nave and transept sit behind an interior passage and yet another arcade that create the effect of a multi-layered wall. Soaring over this multitude of arches are gargantuan ribbed groin vaults that covered the broad main area of the church, were probably the earliest and certainly the widest in Norman architecture. Their lightness and clever variations in curvature and height attest to the technical prowess of the builders. Stonemasons embellished the arches and piers with intricately carved patterns, and incised the outer wall of the aisle with interwoven arches. With these layers and details, the cathedral’s builders and masons emphasized the colossal weight of stone that supports the vaults, while at the same time diffusing this effect of weightiness using surface ornamentation. Together the technically demanding vaults and the wealth of hand-carved decoration broadcast the power of the cathedral and its bishop, who had the means to command the materials and artisans necessary to build such a monument.

Interior of Durham Cathedral, Norman construction founded 1093 (Durham, England) (photo: Simon Varwell)

Led by a decisive ruler, the Norman invaders at the beginning of the eleventh century brought with them a rich set of artistic and architectural approaches that helped them display their new power and authority over the Anglo-Saxon population.

Cite this page as: Dr. Diane Reilly, “The Art of Conquest in England and Normandy,” in Smarthistory, May 5, 2017, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-art-of-conquest-in-england-and-normandy/.

Bayeux Tapestry

Viewing the Bayeux tapestry at the Bayeux Tapestry Museum; Bayeux tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum; photo: boris doesborg, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Map showing the location of the Battle of Hastings (underlying map © Google)

Measuring twenty inches high and almost 230 feet in length, the Bayeux Tapestry commemorates a struggle for the throne of England between William, the Duke of Normandy, and Harold, the Earl of Wessex. The year was 1066—William invaded and successfully conquered England, becoming the first Norman King of England (he was also known as William the Conqueror).

The Bayeux Tapestry consists of seventy-five scenes with Latin inscriptions (tituli) depicting the events leading up to the Norman conquest and culminating in the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The textile’s end is now missing, but it most probably showed the coronation of William as King of England.

Falconer (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

Although it is called the Bayeux Tapestry, this commemorative work is not a true tapestry as the images are not woven into the cloth; instead, the imagery and inscriptions are embroidered using wool yarn sewed onto linen cloth.

The tapestry is sometimes viewed as a type of chronicle. However, the inclusion of episodes that do not relate to the historic events of the Norman Conquest complicate this categorization. Nevertheless, it presents a rich representation of a particular historic moment as well as providing an important visual source for eleventh-century textiles that have not survived into the twenty-first century.

Normans with horses on boats, crossing to England, in preparation for battle (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

The Bayeux Tapestry was probably made in Canterbury around 1070. Because the tapestry was made within a generation of the Norman defeat of the Anglo-Saxons, it is considered to be a somewhat accurate representation of events. Based on a few key pieces of evidence, art historians believe the patron was Odo, Bishop of Bayeux. Odo was the half-brother of William, Duke of Normandy. Furthermore, the tapestry favorably depicts the Normans in the events leading up to the battle of Hastings, thus presenting a Norman point of view.

Bishop Odo rallying William the Conqueror’s troops at the Battle of Hastings (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum)

Most importantly, Odo appears in several scenes in the tapestry with the inscription ODO EPISCOPUS (abbreviated “EPS” in the image above), although he is only mentioned briefly in textual sources. By the late Middle Ages, the tapestry was displayed at Bayeux Cathedral, which was built by Odo and dedicated in 1077, but its size and secular subject matter suggest that it may have been intended to be a secular hanging, perhaps in Odo’s hall.

We do not know the identity of the artists who produced the tapestry. The high quality of the needlework suggests that Anglo-Saxon embroiderers produced the tapestry. At the time, Anglo-Saxon needlework was prized throughout Europe. This theory is supported by stylistic analysis of the depicted scenes, which draw from Anglo-Saxon drawing techniques. Many of the scenes are believed to have been adapted from images in manuscripts illuminated at Canterbury.

The death of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

The artists skillfully organized the composition of the tapestry to lead the viewer’s eye from one scene to the next and divided the compositional space into three horizontal zones. The main events of the story are contained within the larger middle zone. The upper and lower zones contain images of animals and people, scenes from Aesop’s Fables, and scenes of husbandry and hunting. At times the images in the borders interact with and draw attention to key moments in the narrative (as in the image above of the battle).

The seventy-five episodes depicted present a continuous narrative of the events leading up to the Battle of Hastings and the battle itself. A continuous narrative presents multiple scenes of a narrative within a single frame and draws from manuscript traditions such as the scroll form. The subject matter of the tapestry, however, has more in common with ancient monumental decoration such as Trajan’s Column, which typically focused on mythic and historical references.

Servants preparing food (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

The embroiderers’ attention to specific details provides important sources for scenes of eleventh-century life as well as objects that no longer survive. In one scene of the Normans’ first meal after reaching the shores of England, we see dining practices. We also see examples of armor used in the period and battle preparations. To the left of the dining scene, servants prepare food over a fire and bake bread in an outdoor oven (above). Servants serve the food as the tapestry’s assumed patron, Bishop Odo, blesses the meal (below).

The Normans’ first meal in England, at the center is Bishop Odo, who gazes out as he offers a blessing over the cup in his hand.(detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

Immediately after dining, William and his half-brothers Odo and Robert meet for a war council. Preparations for battle flank both sides of the first meal episode (below).

Preparations for war, including the building of a motte-and-bailey (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

Here we see visual evidence of eleventh-century battle gear and the construction of a motte-and-bailey to protect the Normans’ position. A motte-and-bailey is a fortification with a keep (tower) situated on a raised earthwork (motte), surrounded by an enclosed courtyard (bailey). Images of battle horns, shields, and arrows as crucial ammunition shed light on military provisions and tactics for the time period.

Cavalry and foot soldiers in battle (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

William’s tactical use of cavalry is displayed in the “Cavalry” scene. The cavalry could advance quickly and easily retreat, which would scatter an opponent’s defenses allowing the infantry to invade. It was a strong tactic that was flexible and intimidating. Although foot soldiers are included in the tapestry, the cavalry commands the scene, thus presenting the impression that the Normans were a cavalry-dominant army.

Wounded soldiers and horses (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

In addition to depicting military tactics used in the Norman Conquest, the scene also provides visual evidence for eleventh-century battle gear. Cavalrymen are shown wearing conical steel helmets with a protective nose plate, mail shirts, and carrying shields and spears whereas the foot soldiers are seen carrying spears and axes. Representations of the cavalry show that the soldiers were armored but the horses were not. The brutality of war is evident in the battle scenes. Figures of mortally wounded men and horses are strewn along the tapestry’s lower zone as well as within the main central zone.

The Bayeux Tapestry provides an excellent example of Anglo-Norman art. It serves as a medieval artifact that operates as art, chronicle, political propaganda, and visual evidence of eleventh-century mundane objects, all at a monumental scale. This astounding work continues to fascinate.

Cite this page as: Dr. Kristine Tanton, “The Bayeux Tapestry,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-bayeux-tapestry/.

Durham Cathedral

Durham Cathedral (Durham, England), begun c. 1093. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Durham Cathedral from the northwest, begun 1093 (photo: mattbuck, CC BY-SA 2.0)

A building boom

Despite being perched, somewhat snugly, between a cliff above the River Wear to its west and an abrupt incline to the east, the cathedral complex at Durham (begun 1093) was built almost to the largest proportions its tiny peninsula would allow. With walls regularly exceeding three meters in thickness and a final length of more than four hundred feet, it was once counted among the largest and most ambitious structures, not only of its generation, but almost of any following the decline of Roman imperial power in western Europe.

Between the late fifth and early twelfth centuries in fact, only three churches in western Europe could rival the size of Old St Peter’s in Rome. That enormous church was begun by the Roman Emperor Constantine in 318 C.E., soon after the Roman Empire (which included England) became officially Christian. In England, however, ground was broken on nine such giants—including Durham—in less than a generation. What sparked this building boom in the late eleventh century?

In September 1066, thousands of invaders led by William, the Duke of Normandy (also known as William the Conqueror) crossed the English Channel from Normandy (Northern France). The last pre-Norman King of England (Edward the Confessor) had died without a direct heir. By Christmas, 1066, William had been crowned King of England.

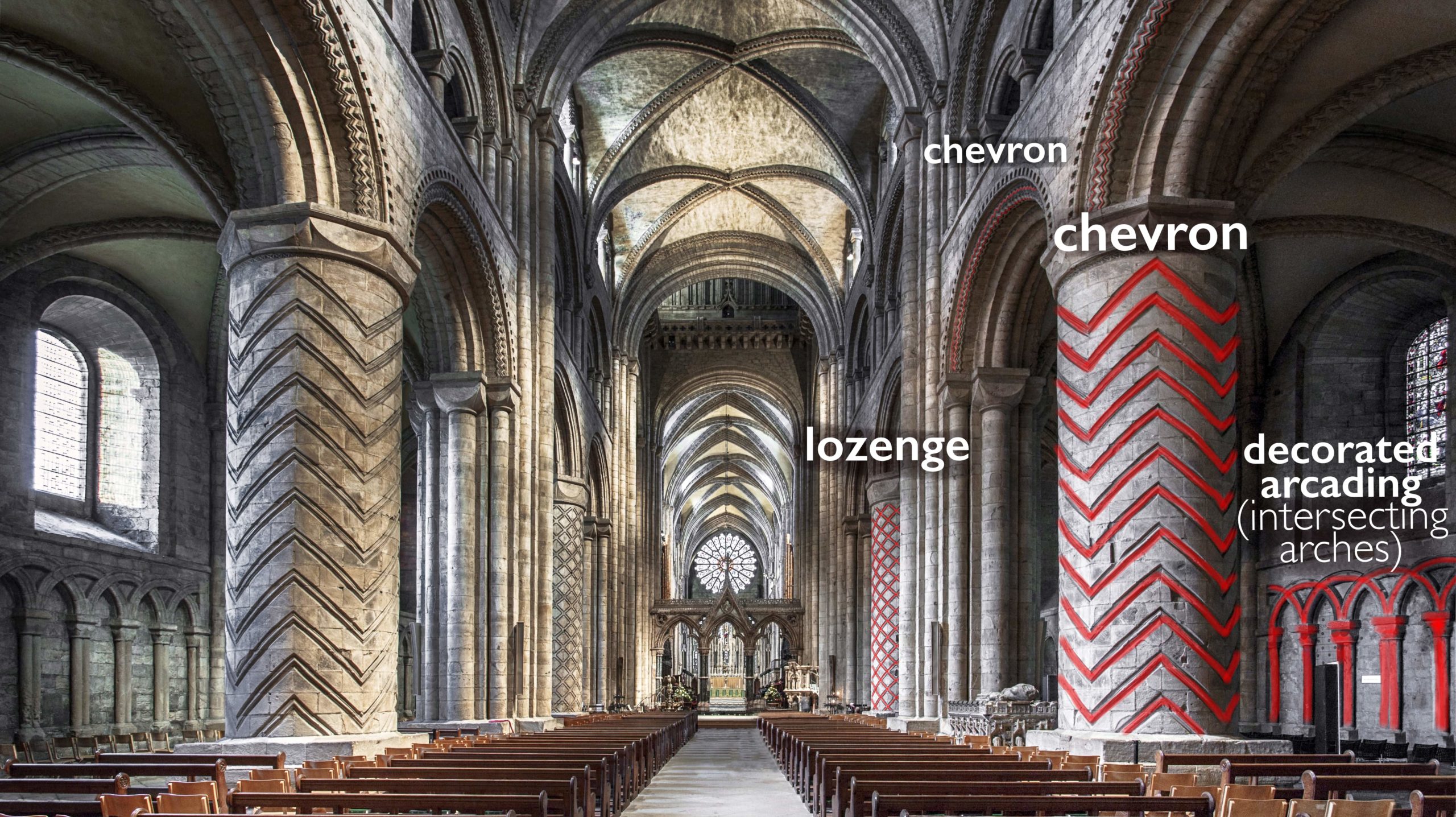

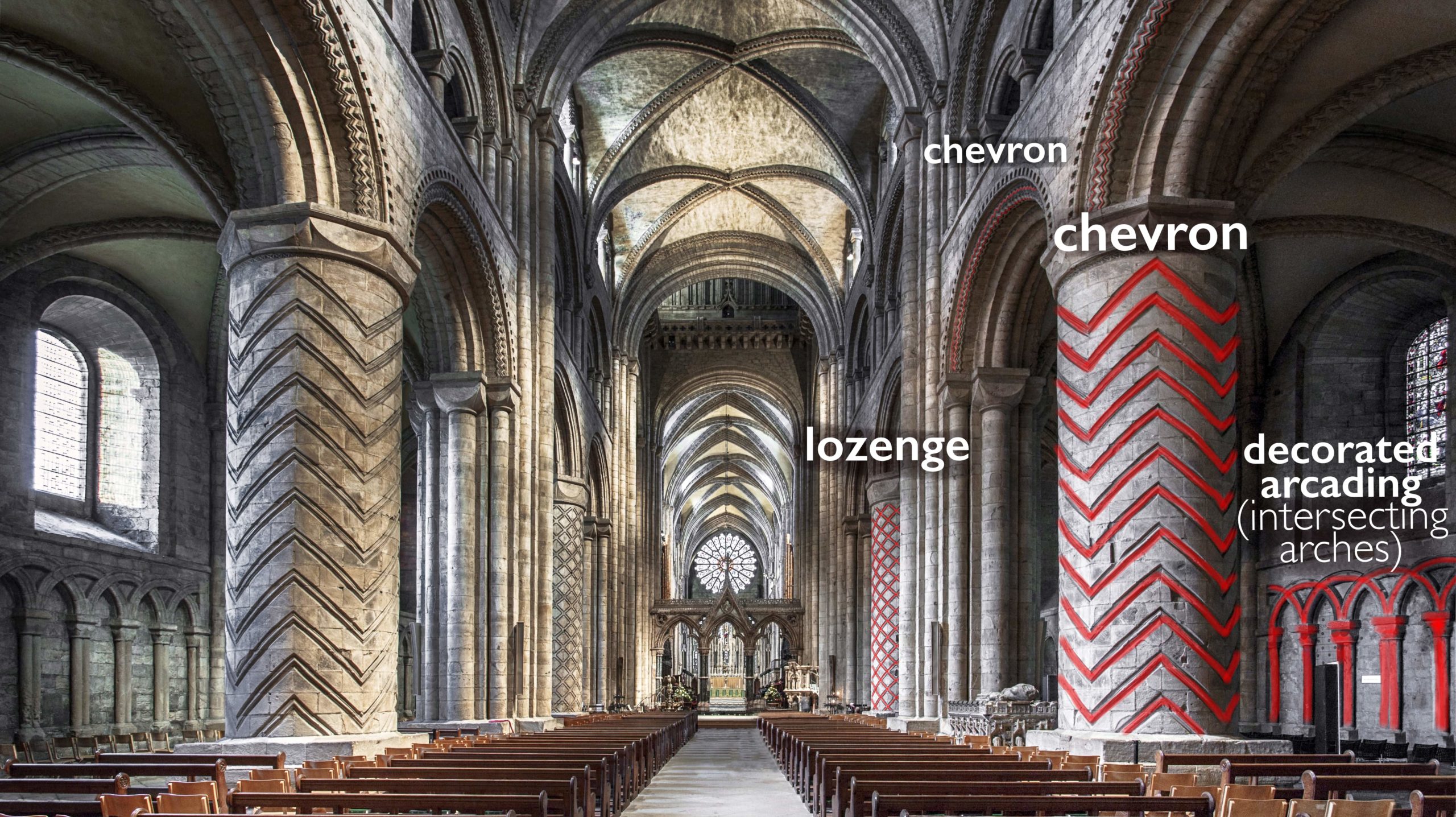

Nave, Durham Cathedral

decorative motifs, nave, Durham Cathedral

Durham Cathedral is one measure of the swift and profound transformation brought about by the Norman Conquest in England in the eleventh and twelfth centuries: not only a new art and architectural style—what is variously referred to as Anglo-Norman or English Romanesque—but an unprecedented and almost military-industrial mode of construction. Another was the sudden influx of architectural elements such as rounded arches, supremely thick walls, alternating piers and columns, barrel vaults, and decorative arcading, among other motifs, that defined Norman and early Christian architecture on the Continent. “England was being filled everywhere with churches,” wrote one bishop named Herman from Ramsbury, “. . . they were magnificent, marvellous, extremely long and spacious, full of light and also quite beautiful.” [1]

Durham Cathedral (photo: alljengi, CC BY-SA 2.0)

No written sources from the period are known to argue that a cathedral should be made large or, for that matter, why. And yet it is obvious from their sheer concentration that architectural gigantism must have been thought to carry a very powerful socio-political endowment. Dozens of fortified strongholds, castles, and halls followed within eighteen months of the invasion, and many hundreds of smaller parishes, priories, chamber blocks, water mills, and houses rose in tandem. It was, in all likelihood, nothing less than the most prodigious building program in Europe, by volume, per capita, prior to the Industrial Revolution.

Galilee chapel (begun 1175), Durham Cathedral (photo: Nick Thompson, CC BY-NC 2.0)

A new kind of sculptural decoration

And yet, despite having the plan, the scale and elevation of a more or less classic Norman cathedral, Durham was also exhaustively dressed in a curious new kind of atypical sculpture. Bold linear carvings abounded: chevrons (or zigzags), lozenges, and even spirals.

Inside the cathedral there was scarcely any surface—from the vaults to the arcading to the piers—that was not extravagantly embellished in some way (whether by chisel or by brush). In fact, by almost every standard, not only of design but of execution—the proficiency of jointing and angling, the near metronomic consistency of stone cutting, as well as the sheer finesse and precocity of its ornamentation—the masons’ work at Durham looks as if belongs in an entirely different world.

Intersecting arches. Left: Great Mosque, Córdoba (9th–11th century); Aljafería in Saragossa (11th century); Durham Cathedral (12th century)

Precedents

Exactly which world has long been a matter for debate. Some art and architectural historians have made connections with earlier medieval Spain, Germany and France. The intersecting arcades at Aljafería in Zaragoza and, before it, the Great Mosque of Córdoba both make for intriguing alliances. Several cathedrals (including those at Mainz and Speyer) are interesting also for their shared size and extravagance. [2] None of these can be easily ignored (and I hesitate to rush through them). But there is still something like a broad if often quiet consensus that very few, if any, of these connections can be thought to be definitive (and certainly not singular influences) on Durham’s plan or execution.

Precisely where and/or when Durham’s masons derived any inspiration notwithstanding—and it’s probable, of course, that we’ll never know for sure—these analyses only stand to shed so much light on how and why these carvings actually functioned in practice. A better question might be: how they were encountered, how were they thought about by medieval men and women?

Spiral columns in the transept (Google Street View)

On the one hand, Durham’s uniquely elaborate surfaces could simply have been ornamental—that’s to say l’art pour l’art (art for art’s sake). It’s certainly been argued that the richer articulation of early medieval sculpture and painting was often commensurate with a desire to flaunt status or worth. Not insignificant therefore is the fact that the east end, the chancel, Saint Cuthbert’s shrine, his altar and the transepts—the spaces that most closely surrounded the saint’s remains—were the most ornate. Cuthbert, whose body was said to have been unearthed from its grave still flawless and even sweet-smelling (more than ten years after his death), was easily the most renowned saint in the north of England. The additionally lavish embellishment of his resting place may therefore have reflected a fitting relationship between decoration and dignity.

Arch in the cloister, Durham Cathedral (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

On the other hand, might these extraordinarily idiosyncratic forms also have embodied some kind of information or message, a means perhaps to communicate? Witnesses and evidence are in short supply, with a single shining exception. Symeon of Durham was a monk and, for some time, the Cantor at Durham Cathedral. He is one of fewer than a dozen people known to have been in attendance at the building’s ground-breaking in 1093 as well as the formal interment of St. Cuthbert’s body, just over a decade later. Symeon effectively alleged that the destruction of the old church, and this new church—with its reformed clergy—is what Cuthbert would have wanted all along. Perhaps like Symeon, the new cathedral’s masons (and he may have been one of them) were largely working without precedent towards the evocation of the architecture of Cuthbert’s ancient past.

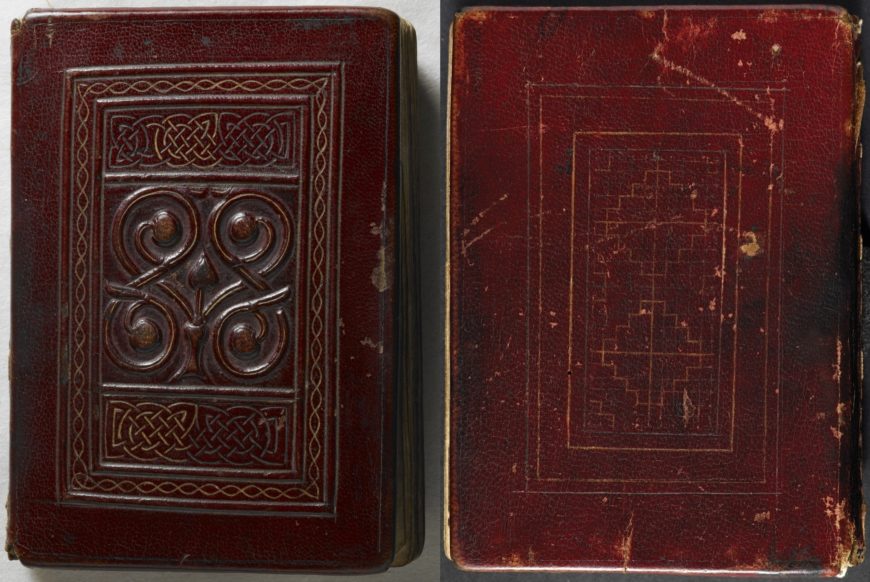

That being said, many other decorative motifs that did survive from seventh- and eighth-century Northumbria—the years during and immediately after Cuthbert’s lifetime—do share a similar and pronounced interest in the complex interplay of line, pattern and surface texture.

The carpet page opening the Gospel of St Matthew in the early eighth-century Lindisfarne Gospels is a classic and exceptional example, as is, of course, the St Cuthbert Gospel itself. Having been placed in Cuthbert’s tomb in 698 on the occasion of his translation to the high altar at Lindisfarne (in Northumbria), this book and its original binding was unexpectedly found—or so the story goes—only eleven years after construction at Durham began. In the bold plastic articulation of the raised interlace on its upper cover, and especially in the schematic square settings of its lower cover it is easy to get a sense of a shared tradition.

Evoking an earlier, imagined medieval style?

Put another way, Durham’s strange new sculpted forms may appear familiar yet unspecific, evocative yet alien, or they might seem only loosely reminiscent of some kind of earlier medieval style—now as then—because they weren’t so much copied as they were imagined. If, like its southern counterparts—Canterbury (begun 1067), Winchester (begun 1079), Ely (begun 1079), St Augustine’s (begun c. 1080), or Old St Paul’s (begun 1087)—the massive chassis of Durham Cathedral did indeed function as something like its “hard” power then its interior fabric, its extraordinarily ornate surfaces, perhaps hinted at a much “softer” kind of meaning.

This extraordinary building is regularly described as a kind of brilliant late-Romanesque lynchpin, linking with and pre-empting the nascent proto-Gothic style in its use of pointed arches. On account of its sheer precision, its scale, its vaulting and—in particular—its precocious pointed ribs, Durham has come to represent a sparkling new apogee, not only to the first generation of post-Conquest building, but to a continent-wide narrative of “progressive” structural experimentation. Do bear all of these twentieth-century assessments in mind when you visit the cathedral. And yet, perhaps take at least one further moment to imagine how the twelfth-century masons at Durham may actually have spent much of their time looking, not to the new, nor to the future, but somewhat nostalgically to a very foggy and distant past.

Notes:

[1] For a modern translation, see Richard Gem, ‘The English Parish Church in the Eleventh and Early Twelfth Centuries: A Great Rebuilding?’, in Minsters and Parish Churches: The Local Church in Transition, 950-1200, ed. by John Blair (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1988), p. 21.

[2] Among other possible precedents are the columns painted in imitation of veined marble at Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe (begun c.1050) and Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand (begun c.1050). Durham may also have shared a common prototype, now lost, with the small parishes of pre-Conquest Wittering (begun ca. 1050), Stow (begun ca. 1040), Great Paxton (begun ca. 1050), St Wystan’s (begun ca. 725), or St Botolph’s (begun 1020).

Additional resources

Durham Cathedral

Durham Castle and Cathedral at UNESCO

Durham Cathedral: History Fabric and Culture, ed. by David Brown (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015)

Anglo-Norman Durham, 1093–1193, ed. by David Rollason, Margaret Harvey and Michael Prestwich (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 1994)

Medieval Art and Architecture at Durham Cathedral: The British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions for the Year 1977, ed. by Nicola Coldstream and Peter Draper (Leeds: British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions, 1980.

Cite this page as: Euan McCartney Robson, “Durham Cathedral,” in Smarthistory, April 9, 2021, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/durham-cathedral/.

English Castles

The traditional view of a medieval English castle is that it was designed for warfare, suggesting that medieval lords were perpetually either at war or preparing for it. Until recently castles were mostly studied by military men or at least by men with a military background who had fought in one of the two world wars. Their work on castles extended their interest in warfare back to an earlier period and into an area which had been little studied in comparison with religious architecture. For these men, castles were defined as strongly fortified residences, and both elements, fortification and accommodation, must be present if a building is to be a castle. More recently many scholars have argued that castles had more to do with factors other than warfare, such as dominating the landscape, and that they are best seen as an architectural expression of the social status of their owners.

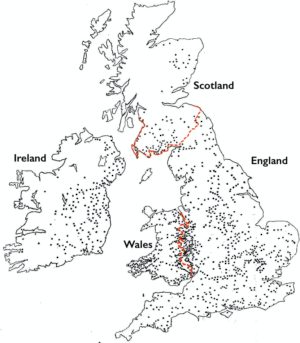

It is accepted by the archaeologists who have excavated them that castles were introduced to England by the Normans (who came from Normandy in Northern France, and conquered England in 1066). The typical form was a wooden keep (a fortified tower) built on top of a motte (a mound of earth), the whole surrounded by a ditch.

Mountfitchet Castle, Essex (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

A reconstruction of a Castle has been created at Stansted Mountfitchet (in Essex), by building a fence made of chestnut wood palings around the top of a motte which dates to the time of the Normans, and calling it a “Medieval Experience.” Only a few Norman mottes ever became fully fledged stone castles (the earliest Norman castles were built of timber and earth).

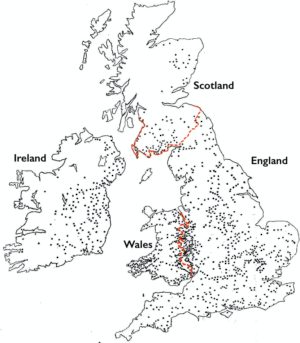

Distribution of Norman mottes – each dot is a motte

A glance at the distribution map shows that there was a heavy concentration of mottes along the borders between England and Wales and Scotland, but otherwise they were evenly spread across populated areas. Apart from the strategic border castles that were genuinely intended either to guard against invaders or to act as garrisons for raids into Wales, mottes were built in cities, boroughs and practically every town of any size. It was not that the Normans were expecting attacks from the townspeople or even those of the neighboring town. Rather they were building physical statements of their dominance. These mottes are not very high as a rule, and they didn’t need to be to tower over a cluster of surrounding buildings that were little more than huts made of wattle and mud.

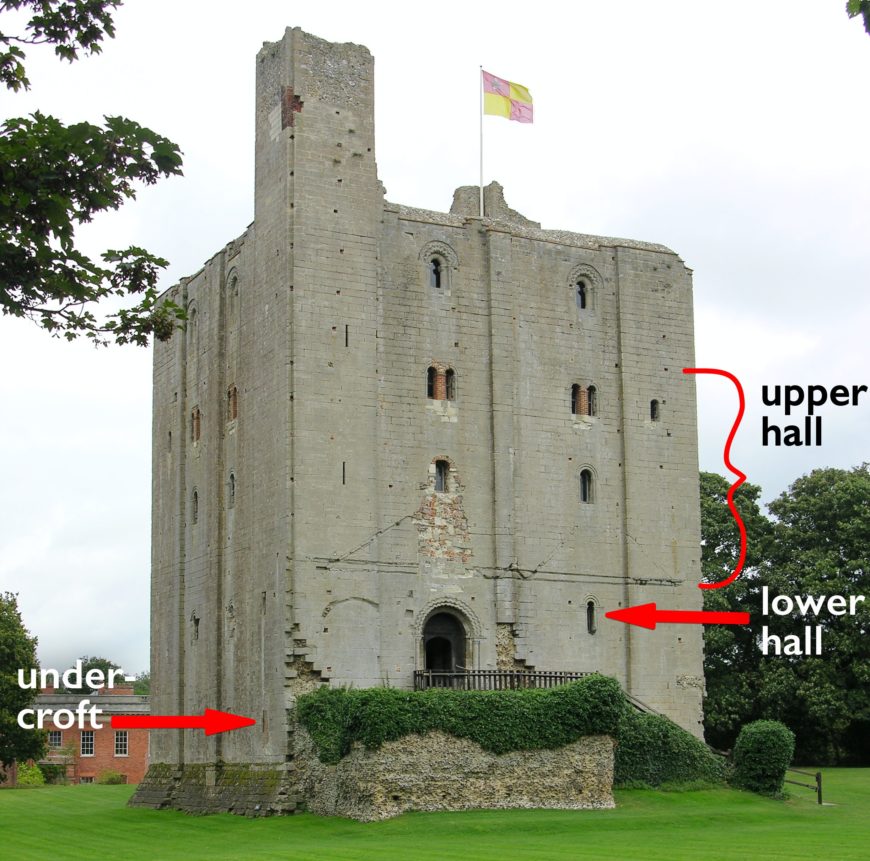

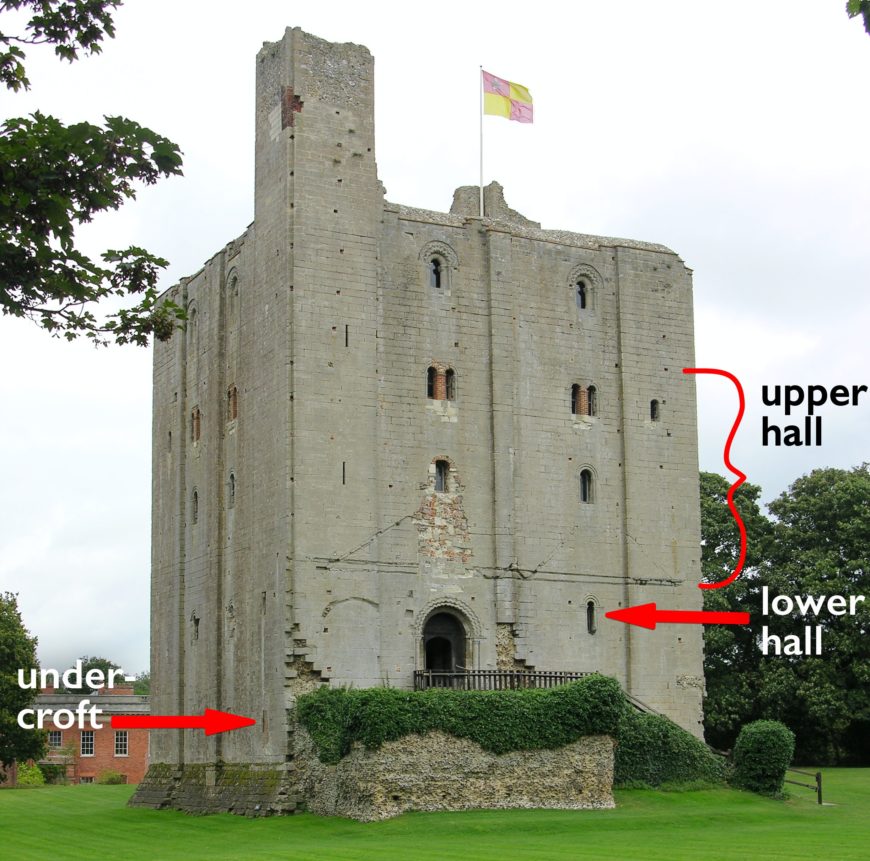

Hedingham Castle keep from the Southwest (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Hedingham Castle

Hedingham Castle in Essex is one of the strongest and most impressive castles in Eastern England, and it was built by one of the richest and most powerful families, the de Veres, Earls of Oxford, most probably in the 1140s. It was an expensive project: there is no suitable local stone, and the high-quality limestone used to build it had to be carted eighty miles from the quarries at Barnack in Northamptonshire. Its tall keep rises to a height of almost 100 feet and dominates the flat surrounding landscape for miles in every direction. This business of height is important. The taller a building, the less stable it is. A genuinely defensive building should be low and squat. But at Hedingham visual prominence is the important factor.

A close examination of the keep shows that a lot of the height is fake.

Hedingham Castle keep showing floor levels

There is an undercroft (a lower hall at the level of the main doorway), and a double-height upper hall with two rows of windows, and that is all. The row of windows at the top were originally above the roof so that this whole upper storey was open to the sky. It was later roofed in and called the dormitory, but the roof is modern, and the inner walls were never plastered because they were outside.

Hedingham Castle top floor (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The false upper storey was not unusual in the Norman period—the White Tower, William the Conqueror’s keep at the Tower of London, was just the same.

This is not the whole story, of course. Castles were luxurious residences too. The luxury is not usually obvious because most castles are ruined nowadays, but the evidence is there to be found. At Hedingham there are richly chevron-decorated arches, fireplaces with carved capitals. and plastered walls, sometimes with traces of painted decoration still surviving.

Hedingham Castle, upper hall (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Rochester Castle

Castles could also be genuinely defensible, but not without preparation and a special effort. During the Barons’ War against King John in the early thirteenth century Rochester Castle in Kent was held by a large garrison of about 100 of the barons’ men.

Rochester Castle keep with the cathedral in the background (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Portcullis slots at Corfe Castle, Dorset (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Rochester Castle was reputed to be the strongest castle in the kingdom—a coastal castle genuinely built for defense. It was besieged by the king for almost fifty days by a large force with engines, battering rams and crossbows, but held out.

Eventually the king employed miners with picks to dig underneath the foundations, propping up the tunnels with timbers, and then setting fire to them using pig-fat to feed the flames. The tunnels collapsed and the tower above them fell, but the defenders continued to hold out in the ruin until they were starved out. Later, however, the barons called on the help of Prince Louis of France, who landed in Kent and proceeded to take all the chief castles of south-east England in rapid succession: Berkhamsted, Cambridge, Colchester, Hertford, Norwich, Orford, Winchester, Hedingham and Pleshey.

This suggests that castles could resist a siege, but only under special circumstances, and those include siting—Rochester is at the mouth of the River Medway, which limits the attackers’ means of approach—and it had a large garrison as well as defensive architectural features. These features could include ditches or moats crossed by bridges with removable central sections, or gatehouses with drawbridges and portcullises, battlements with walkways and machicolations (an opening through which stones or burning objects could be dropped on attackers), and plans designed to make would-be invaders into sitting targets by ensuring that the only access route to the castle was exposed to archers on the battlements. This could be done by building the castle on a man-made or natural hill, and using a moat to slow their progress.

Fortification and Residence

As explained above, the traditional definition of a castle is that it is a fortified residence, and both elements—fortification and residence—are essential before something can be called a castle. The work of recent writers like Robert Liddiard, Oliver Creighton, and Matthew Johnson presents a very different and more complex idea of how castles worked. First there has been a tendency to downplay the military aspect, not least by pointing out that most castles were never under siege. The rules of medieval warfare were designed to avoid genuine sieges. A full-scale siege required enormous resources of men and horses, siege engines had to be constructed and dragged into position, and men committed for weeks or months to operating them and finding suitable ammunition. If the defenders surrendered, they should be allowed to march away unharmed, while the attackers gained only a ruined castle. In practice a siege was usually unnecessary because castles could simply be bypassed by invading forces wishing to advance.

John Goodall has suggested a new definition of a castle as “the residence of a lord made imposing through the architectural trappings of fortification, be they functional or decorative” (Goodall, 2011, p.6). This introduces the idea of fortification as an architectural style, which has much to commend it.

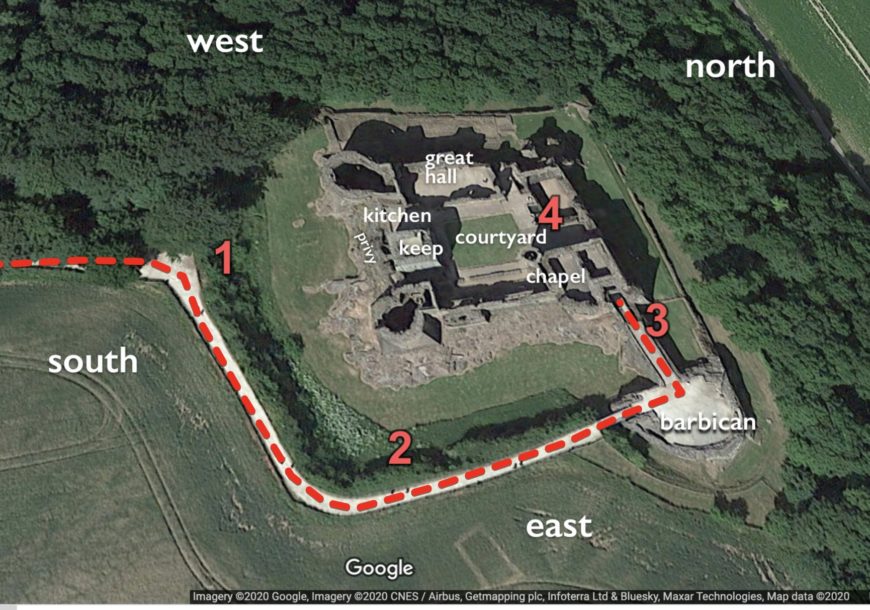

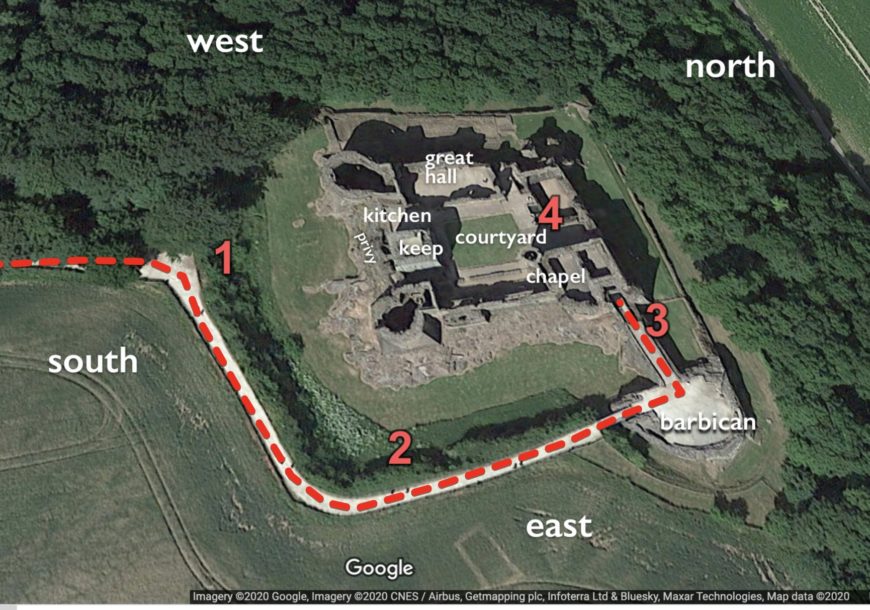

Goodrich Castle

Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire is strategically placed on a sandstone outcrop overlooking the river Wye, near the border between England and Wales. Goodrich reached its full medieval development in the fifteenth century. It was never under siege or serious attack until the English Civil War of the seventeenth century.

To properly understand the way castles worked it is important to try to see them as their users saw them, which can be difficult because there are always additions and losses and, most importantly, there are no longer any inhabitants.

Plan, Goodrich Castle

A knight visits the castle

Let’s try to put ourselves in the position of a medieval visitor of high status — a knight in the fifteenth century.

View #1: the approach to Goodrich Castle (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Goodrich: the approach to the castle

As usual there is just one main approach road. The lower orders might do something slightly different, but our knight simply follows the road and is led by the clues it gives. He approaches from the south with his retinue and gains his first view of the castle. In the center he sees a big square building (the keep), obviously older than the rest, which tells him that the castle is ancient—he is visiting a venerable family (in fact the Talbot Earls of Shrewsbury).

View #2: Goodrich Castle, east side (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) (Google street view)

The knight follows the road to the right, around the south-east tower, and sees the east side of the castle, originally reflected in the water of the moat, doubling its size. It has an impressive curtain wall with battlements and arrow slots. Immediately beyond the round corner tower, he sees a newly installed three-seater garderobe or privy — the last word in late-medieval plumbing. Imagine the sight and the smell as he rounds that corner and sees the human waste staining the walls as it drops into the moat. Matthew Johnson has argued that this was an important part of the castle experience, and that all that shit and food waste would have impressed the visitor with the wealth of the occupants and the lavishness of their table. Throughout the ride along the east side, our knight is separated from the castle by a deep moat, but he is observed by watchers on the battlements who will give warning of his approach. An attacking force would be most vulnerable at this stage.

View #3: the approach to Goodrich Castle from the Barbican (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) (Google street view)

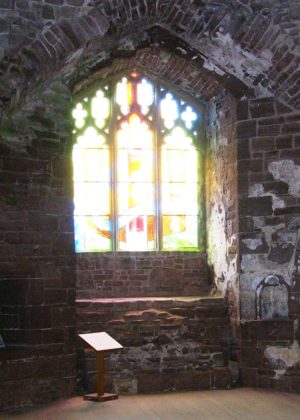

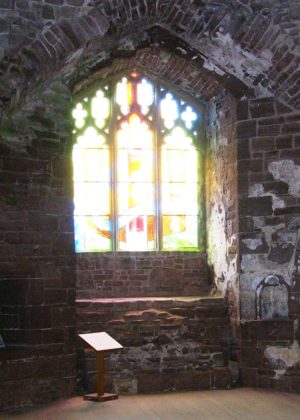

The knight rides on and reaches the barbican—a fortified outwork where he sees the gateway ahead and must dismount. No horses were allowed inside the castle. Retainers dressed in the Talbot family livery take his horse to the stables. All the servants wear the badge of the Lord so our knight can never forget whose roof he is under. To the left of the gateway he sees a chapel — recognizable by its traceried window.

He walks under the gateway and sees murder holes overhead. Perhaps he looks upwards and feels nervous as he sees the portcullis and the murder holes, through which molten lead could be poured on invaders.

Goodrich Castle gateway with murder holes overhead (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

These so-called defensive features were not designed to deter a large force (which would probably bombard the walls rather than using the gatehouse), but to impress a single man or a small group.

View #4: Goodrich Castle: the courtyard seen from the gatehouse (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) (Google street view)

The knight emerges into the central courtyard and immediately knows where he is — even if he has never been here before— because the elements of a castle were the same everywhere. The building on the right is the Great Hall, with the dining hall in the centre, the Lord’s lodgings at this end, the high end, and the kitchen at the far end.

As a visitor our knight will use the entrance at the low end, between the kitchen and the hall itself, but he cannot simply walk in. There is a lobby area with benches for visitors to wait until the Lord is ready to receive them.

Goodrich Castle: lobby at the low end of the Great Hall (Great Hall on right, kitchens on left) (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Courtly life was ritualized in this period. The retainers wore their costumes, and the Lord had his part to play like anyone else. A castle was the stage on which social relations were played out, and it was important that all the actors knew their moves and their lines. The similarities between castles were vital to the maintenance of correct social relations, which is why the component parts of a castle were designed to be easily recognizable: the tall window recesses in the Great Hall gave away its function from the exterior, as did the elaboration of the Lord’s private quarters and the traceried windows of the chapel.

Great Hall, Goodrich Castle (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Traceried window, Chapel, Goodrich Castle (photo: Ron Baxter, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

A castle visit can be a haunting experience; the crumbling walls evoking thoughts of medieval warfare and lost grandeur. But also, for historians who can read their messages, castles provide valuable evidence of the way life was lived in the Middle Ages. The problem is how to interpret what we see. Churches and cathedrals still operate today; we know what they do and how the various parts fit together as a setting for the liturgy. Even a ruined monastery is not such a puzzle that we cannot work it out. But castles like those I have looked at here function today as tourist destinations and occasionally as wedding venues. They can be settings for pleasure, ritual, and feasting, but not as they were originally conceived. Their value for the historian is that they provide the physical setting for social life in the Middle Ages, and the effort made to interpret them is generously repaid by the understanding these ruins provide.

Cite this page as: Dr. Ron Baxter, “The English castle: dominating the landscape,” in Smarthistory, December 5, 2020, accessed May 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/english-castle-dominating-landscape/.