Aegis of Isis, Kushite, late 3rd century B.C.E., from Kawa, Sudan (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

The first settlers in northern Sudan date back 300,000 years. It is home to the oldest sub-Saharan African kingdom, the kingdom of Kush (about 2500–1500 B.C.E.). This culture produced some of the most beautiful pottery in the Nile valley, including Kerma beakers.

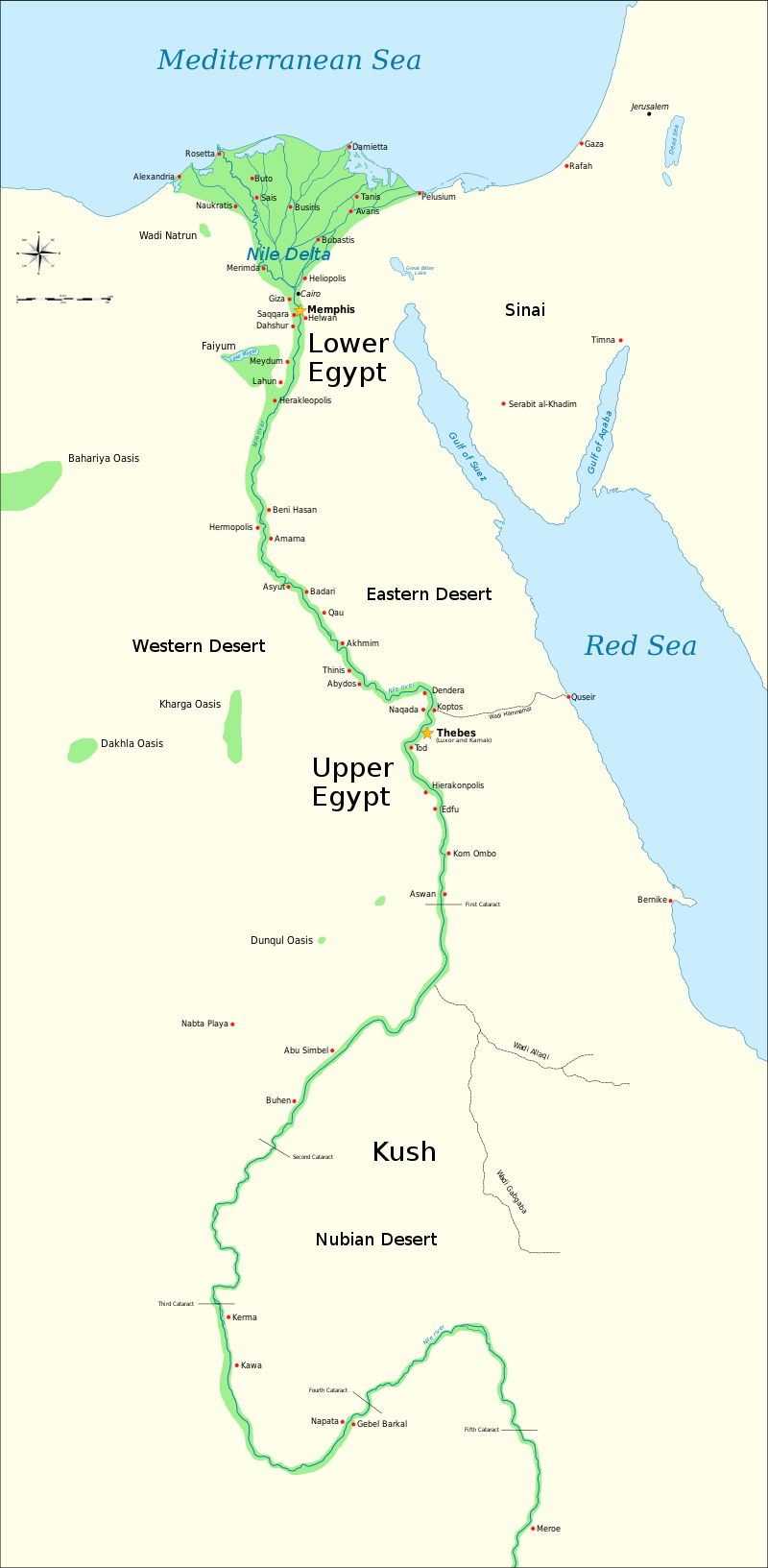

Map of Kush and Ancient Egypt, showing the Nile up to the fifth cataract, and major cities and sites of the ancient Egyptian Dynastic period (c. 3150–30 B.C.E.) (map: Jeff Dahl, CC Y-SA 4.0)

Sudan was coveted for its rich natural resources particularly gold, ebony and ivory. Several objects in the British Museum collection are made of these materials. Ancient Egyptians were attracted southward seeking these resources during the Old Kingdom (about 2686–2181 B.C.E.), which often led to conflict as Egyptian and Sudanese rulers sought to control trade.

Kush was the most powerful state in the Nile valley around 1700 B.C.E. Conflict between Egypt and Kush followed, culminating in the conquest of Kush by Thutmose I (1504–1492 B.C.E.). In the west and south, Neolithic cultures remained as both areas were beyond the reach of the Egyptian rulers.

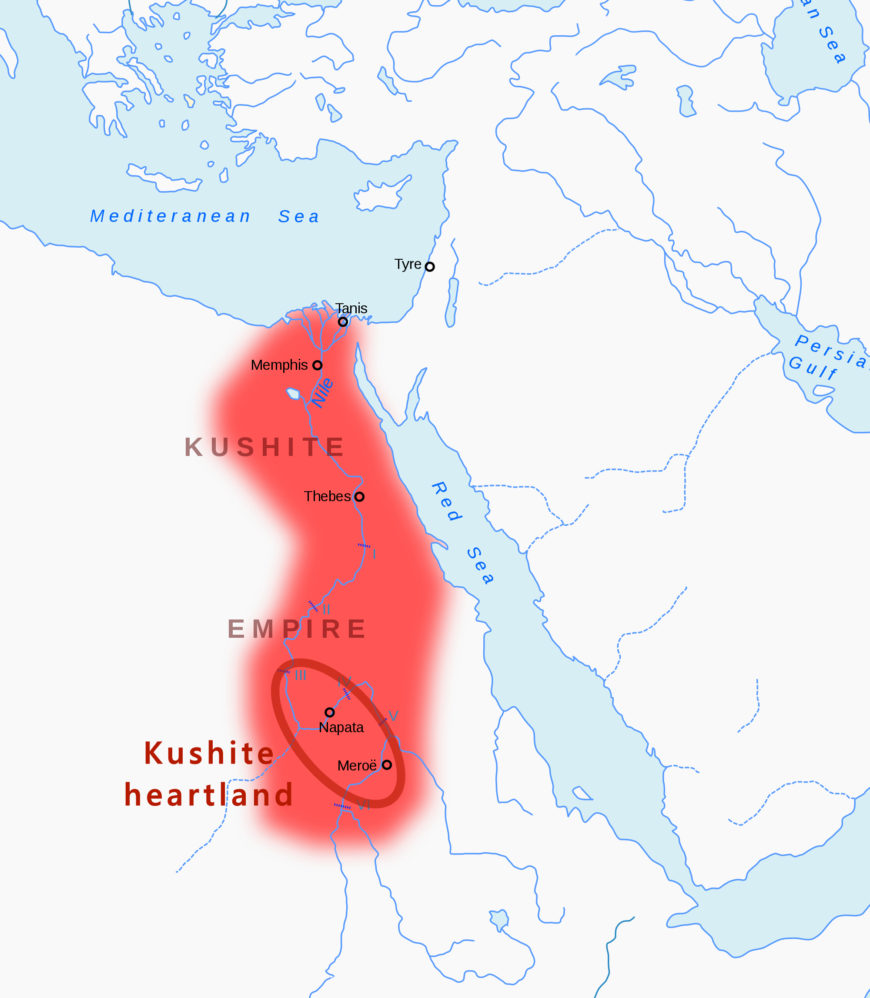

Kushite heartland and Kushite Empire of the 25th dynasty circa 700 B.C.E. (map: Lommes, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Egypt withdrew in the eleventh century B.C. E. and the Sudanese kings grew powerful. They invaded Egypt and ruled as Pharaohs (about 747–656 B.C.E.). At its greatest, their empire united the Nile valley from Khartoum to the Mediterranean. King Taharqo’s sphinx remains a testament to Kushite power and authority.

The Kushites were expelled from Egypt by the Assyrians, but their kingdom flourished in Sudan for another thousand years. Their monuments and art display a rich combination of Pharaonic, Greco-Roman and indigenous African traditions which may be seen in the chapel relief of Queen Shanakdhakete and aegis of Isis in the Museum collection.

Kerma ware pottery beaker, about 1750–1550 B.C.E., from Kerma, Sudan (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Kerma ware pottery beaker

The cultures of Kerma flourished between about 2500 and 1500 B.C.E. Their most distinctive products were ceramics. The potters were able to produce incredibly fine vessels by hand, without using a wheel. The pot shown here belongs to the so-called ‘Classic Kerma’ phase, from around 1750 to around 1550 B.C.E. Classic Kerma pottery is characterized by a black top and a rich red-brown base, separated by an irregular purple-grey band. The black tops and interiors are usually extremely fine and have a distinctive metallic lustrous appearance.

Kerma remained independent during Egypt’s initial forays into Sudan. This situation changed after 1500 BC, when the Egyptians defeated the Kushites and began to administer the area via their representative, the ‘Viceroy of Kush’, based at Kerma.

Black polished incised ware cup, Late C-Group Culture, 1700–1500 B.C.E., from Cemetery 2 at Faras, Sudan (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Black polished incised ware cup

The handmade pottery produced by C-Group craftsmen is highly distinctive. Although some forms are comparable to Egyptian types of the same period, others are quite different. These show a strong African influence.

This cup has features characteristic of the African-influenced group known as ‘polished incised ware’. The cup has a round bottom and is bowl-shaped, though it is small enough to be considered a cup. Vessels of this shape were probably designed to hold food and drink. The African influence is shown most clearly in the cup’s decoration. The exterior is incised with diamonds filled in with cross hatching, perhaps derived from designs used in basket work. Other motifs include herringbone patterns and other geometric shapes of smooth and incised areas.

The incised decoration was applied to the pot before the clay was dry. The vessel was fired to leave a black or sometimes a red finish, which was highly polished. Finally, white pigment was rubbed into the incisions to make the pattern stand out. The remains of the white pigment can be seen in some areas on this cup, but most is now lost.

Sesebi and Egyptian domination

Perfume jar, 18th dynasty, found in a cemetery in Sesebi, southern Nubia (Sudan), 13 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

This beautiful vase was found in a plundered part of the cemetery at Sesebi in southern Nubia. It is an excellent example of the use of faience in a color other than blue. Decoration has been added to the cream body in blue and black, in the form of two friezes of lotus petals at the base and neck, with lotus buds hanging down; the vase itself is in the shape of a lotus bud.

From around 1560 until 1070 B.C.E. the Egyptians took possession of all Nubian lands as far as the Fourth Cataract of the Nile. The newly won land was divided into two territories: Wawat in the north and Kush in the south. Resources were intensively exploited by the Egyptian empire. Many native inhabitants were recruited into Egyptian armies or employed as laborers on Egyptian civil and religious estates.

New towns and temples were built during the period of Egyptian domination, including Sesebi, founded during Akhenaten’s reign (1352–1336 B.C.E.). Many Nubians embraced the language, religion and forms of aesthetic expression of their overlords. This vase shows strong Egyptian influence in shape and style; to ancient Egyptians the lotus was symbolic of rebirth and new life.

A powerful Kushite dynasty emerges

The Egyptians withdrew from Sudan around 1070 B.C.E. and by the ninth century a second powerful Kushite dynasty had emerged there. Taking advantage of instability and political disunity in Egypt, the Kushite king Kashta extended his control to Thebes in Egypt by the mid-eighth century B.C.E. His successor Piankhi (Piye) achieved complete control of the Egyptian Nile valley by around 716 B.C.E. He and his three successors, Shabaqo, Taharqo and Tamwetamani, were acknowledged as the legitimate sovereigns of Egypt, forming the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. Their capital was the important religious centre of Napata, near the Fourth Cataract of the Nile.

Kushite control of Egypt ended when Assyrian forces invaded between 674 and 663 B.C.E., but Kush remained a major power in Sudan for over a thousand years. After 300 BC, the Kushite rulers were buried at Meroe in a fertile grassland region northeast of Khartoum. Meroe became the centre of a flourishing economy and developed commercial links with the Mediterranean world. Art and architecture displayed Egyptian influence, but archaeology also points to a growth of local traditions. A strong local element was apparent in religion, with Nubian deities such as the lion-headed Apedemak appearing alongside the Egyptian Amun, Osiris and Isis. The Kushite dynasty ended around 350 C.E.

The large eyes are typical of Kushite art and the piece bears a cartouche of the Kushite ruler Arnekhamani (235–218 B.C.E.). Aegis of Isis, Kushite, late 3rd century B.C.E., from Kawa, Sudan (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Ornamental head of a goddess, possibly Isis

The term aegis is used in Egyptology to describe a broad collar surmounted by the head of a deity, in this case a goddess, possibly Isis. Representations in temples show that these objects decorated the sacred boats in which deities were carried in procession during festivals. An aegis was mounted at the prow and another at the stern. The head of the deity identified the occupant of the boat and it is likely that this example came from a sacred boat of Isis.

The eyes and eyebrows of the goddess were originally inlaid. The large eyes, further emphasized by the inlay, are typical of later Kushite art. The rectangular hole in her forehead once held the uraeus, which identified her as a goddess. The surviving part of her head-dress consists of a vulture—the wing feathers can be seen below her ears. The vulture head-dress was originally worn by the goddess Mut, consort of Amun of Thebes, but became common for all goddesses. The rest of the head-dress for this aegis was cast separately and is now lost, but would have consisted of a sun disc and cow’s horns. The piece bears a cartouche of the Kushite ruler Arnekhamani (reigned about 235–218 B.C.E.), the builder of the Lion Temple at Musawwarat es-Sufra.

Burials of Kushite kings

Granite shabti of King Taharqa, 25th Dynasty, 664 BC, from the pyramid of Taharqa at Nuri, Nubia, 40.6 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

The early Kushite kings were buried on beds placed on stone platforms in the tombs under their pyramids. These structures were based on the pyramids of Egyptian private tombs of the New Kingdom (about 1550–1070 B.C.E.), but the style of burial was entirely Kushite. King Taharqo (690–664 B.C.E.) introduced more Egyptian elements to the burial, such as mummification, coffins and sarcophagi of Egyptian origin, as well as the provision of shabti figures such as this. These figures were in the style of the Middle and New Kingdoms, the era that the Kushites considered the height of Egyptian culture. The use of stone and the rugged features of these large shabtis are characteristic of early examples.

During period of Kushite control of Egypt, the kings resided mainly at Memphis, and Kushite princesses were appointed to the religious office of ‘God’s Wife of Amun’. The Twenty-fifth Dynasty rulers—Piankhi, Shabaqo, Taharqo and Tamwetamani—brought much-needed stability to Egypt, which had been divided into small areas and governed by local dynasts. Art, architecture and religious learning were revived and Taharqo in particular was an active builder, constructing a number of temples in both Egypt and Nubia. However, it was during Taharqo’s reign that Assyrian invasions forced the Kushites out of Egypt. Control was regained by his successor Tamwetamani (664-656 B.C.E.) but quickly lost again.

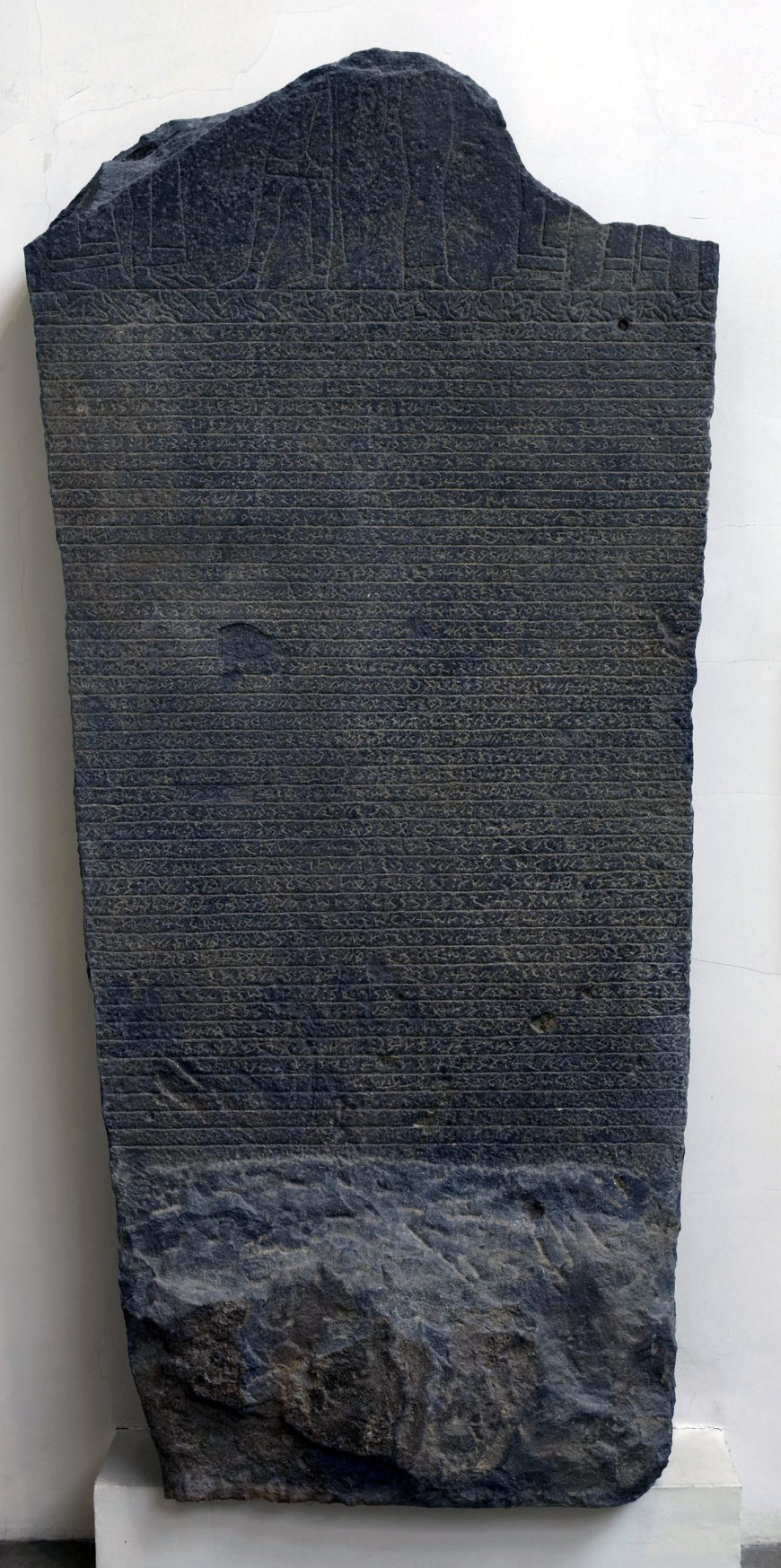

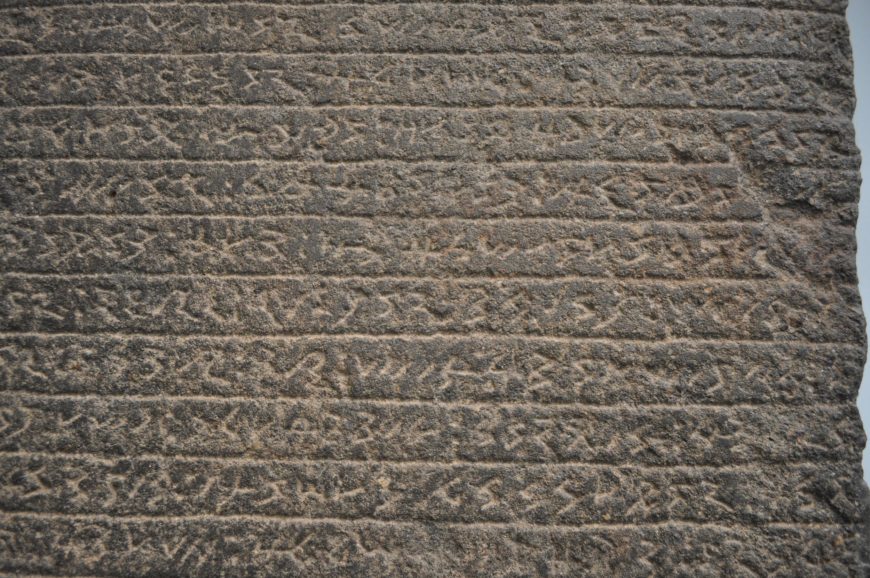

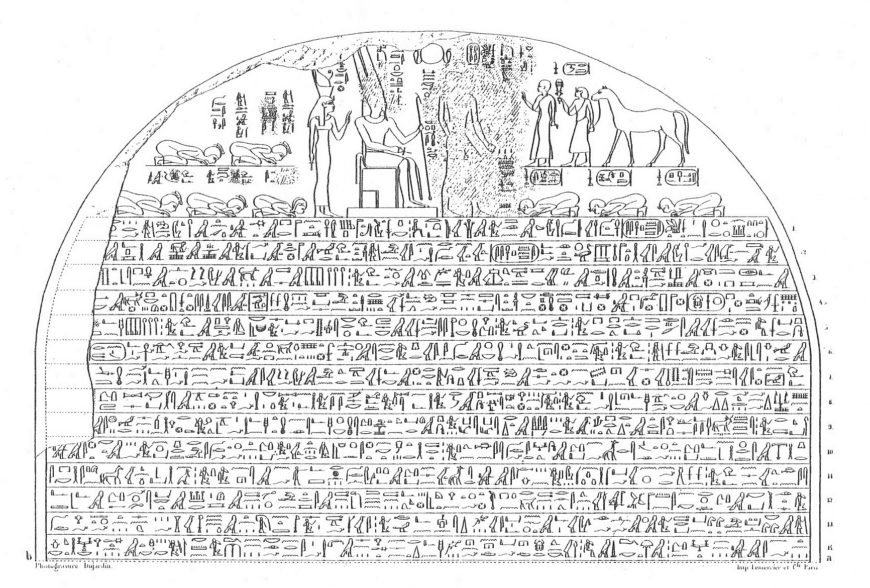

Meroitic stela, Kushite period, about 24 B.C.E., from Hamadab, Sudan, 236.5 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

One of the longest known monumental texts in Meroitic

This stela is one of a pair found at Hamadab a few kilometers south of Meroe in Sudan, the capital of the ancient Kingdom of Kush. They stood either side of the main doorway into a temple.

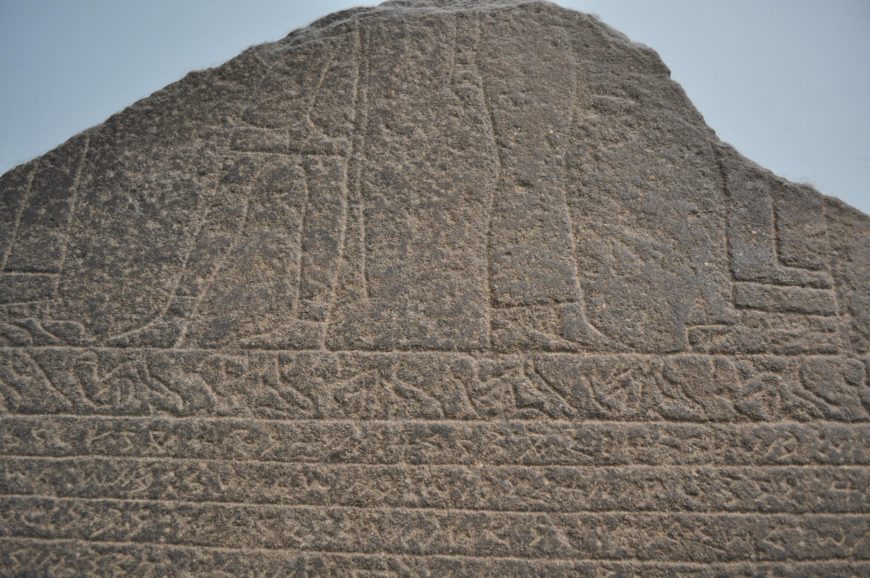

Kushite rulers Queen Amanirenas and Prince Akinidad (detail), Meroitic stela, Kushite period, about 24 B.C.E., from Hamadab, Sudan, 236.5 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

At the top of the stela are the remains of a relief panel depicting the Kushite rulers Queen Amanirenas and Prince Akinidad. On the left they are shown facing a god, probably Amun, whilst on the right they are facing a goddess, probably Mut. Below this is a frieze depicting bound prisoners.

Meroitic stela, Kushite period, about 24 B.C.E., from Hamadab, Sudan, 236.5 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

An inscription in Meroitic cursive script is carved on the lower part of the stela. Meroitic was the indigenous language of the Kingdom of Kush. It is one of the few ancient languages yet to be deciphered. The alphabet consisted of 15 consonants, four vowels and four syllabic characters but the meaning of the words is not known.

In this inscription, the names of Amanirenas and Akinidad are recognizable. It is thought that Amanirenas was the Kushite ruler during the Kushite conflicts against the Romans in the late first century B.C.E. This inscription may commemorate a Kushite raid on Roman Egypt in 24 B.C.E.

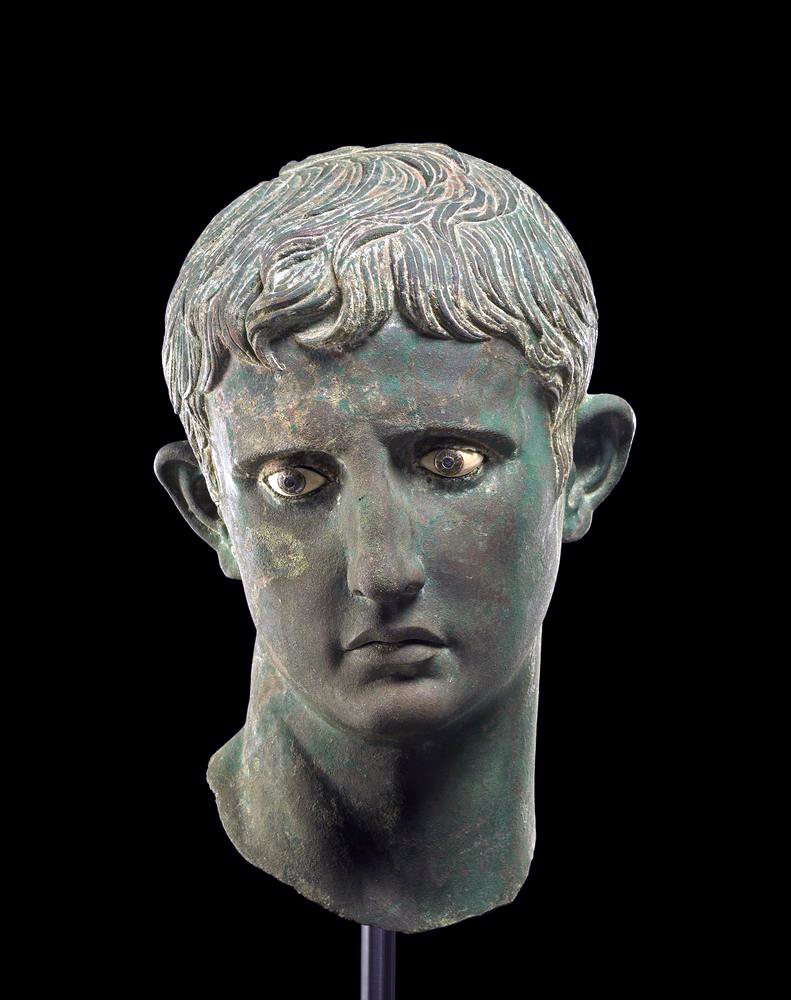

Head of Augustus, c. 27–25 B.C.E. bronze, from Meroë, Sudan, 46.20 x 26.5 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

A number of Roman imperial statues were taken during this raid, possibly including a bronze head of Augustus which was found in Meroë and is now held in the Museum’s collection.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

![]()

Additional resources:

Isma’il Kushkush, “In the Land of Kush,” Smithsonian Magazine (Sep 2020)

S. Quirke and A.J. Spencer, The British Museum book of ancient Egypt (London, The British Museum Press, 1992)

S. Wenig, Africa in antiquity: the arts of ancient Nubia and the Sudan, Vol II, exh. cat. (Brooklyn, N.Y., Brooklyn Museum, 1978)

M.F. Laming Macadam, The temples of Kawa (Oxford, 1949 (vol. I) 1955 (vol. II))

Nigel Strudwick, Masterpieces of Ancient Egypt (London, British Museum Press, 2006)