The oldest art: ornamentation

Humans (Homo sapiens) make art. We do this for many reasons and with whatever technologies are available to us. Recent research suggests that Neanderthals also made art.

Extremely old, non-representational ornamentation has been found across Africa. The oldest firmly-dated example is a collection of 82,000 year old Nassarius snail shells found in Morocco that are pierced and covered with red ochre. Wear patterns suggest that they may have been strung beads. Nassarius shell beads found in Israel may be more than 100,000 years old and in the Blombos cave in South Africa, pierced shells and small pieces of ochre (red Hematite) etched with simple geometric patterns have been found in a 75,000-year-old layer of sediment.

Female Figure of Hohlefels, c. 35,000 B.C.E., ivory, found in cave near Schelklinge, southern Germany (photo: Ramessos, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The oldest representational art

Some of the oldest known representational imagery comes from the Aurignacian culture of the Upper Paleolithic period (Paleolithic means old stone age). Archaeological discoveries across a broad swath of Europe (especially Southern France, Northern Spain, and Swabia, in Germany) include over two hundred caves with spectacular Aurignacian paintings, drawings, and sculpture that are among the earliest undisputed examples of representational image-making. Among the oldest of these is a 2.4-inch tall female figure carved out of mammoth ivory that was found in six fragments in the Hohle Fels cave near Schelklingen in southern Germany. It dates to 35,000 B.C.E.

Left wall of the Hall of Bulls, Lascaux II (replica of the original cave, which is closed to the public), original cave: c. 16,000–14,000 B.C.E., 11 feet 6 inches long

The caves

Warty pig (Sus celebensis), c. 43,900 B.C.E., painted with ocher (clay pigment), Maros-Pangkep caves, Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4, South Sulawesi, Indonesia

The caves at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc, Lascaux, Pech Merle, and Altamira contain the best known examples of pre-historic painting and drawing. Here are remarkably evocative renderings of animals and some humans that employ a complex mix of naturalism and abstraction. Archaeologists that study Paleolithic era humans, believe that the paintings discovered in 1994, in the cave at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc in the Ardéche valley in France, are more than 30,000 years old. The images found at Lascaux and Altamira are more recent, dating to approximately 15,000 B.C.E. The paintings at Pech Merle date to both 25,000 and 15,000 B.C.E. The world’s oldest known cave painting was found in Sulawesi, Indonesia in 2017 and was made at least 45,500 years ago.

What can we really know about the creators of these paintings and what the images originally meant? These are questions that are difficult enough when we study art made only 500 years ago. It is much more perilous to assert meaning for the art of people who shared our anatomy but had not yet developed the cultures or linguistic structures that shaped who we have become. Do the tools of art history even apply? Here is evidence of a visual language that collapses the more than 1,000 generations that separate us, but we must be cautious. This is especially so if we want to understand the people that made this art as a way to understand ourselves. The desire to speculate based on what we see and the physical evidence of the caves is wildly seductive.

Replica of the painting from the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in southern France

Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc

The cave at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc is over 1,000 feet in length with two large chambers. Carbon samples date the charcoal used to depict the two head-to-head Rhinoceroses (see the image above, bottom right) to between 30,340 and 32,410 years before 1995 when the samples were taken. The cave’s drawings depict other large animals including horses, mammoths, musk ox, ibex, reindeer, aurochs, megaceros deer, panther, and owl (scholars note that these animals were not then a normal part of people’s diet). Photographs show that the drawing at the top of this essay is very carefully rendered but may be misleading. We see a group of horses, rhinos, and bison and we see them as a group, overlapping and skewed in scale. But the photograph distorts the way these animal figures would have been originally seen. The bright electric lights used by the photographer create a broad flat scope of vision; how different to see each animal emerge from the dark under the flickering light cast by a flame.

In a 2009 presentation at University of California San Diego, Dr. Randell White, Professor of Anthropology at New York University, suggested that the overlapping horses pictured above might represent the same horse over time, running, eating, sleeping, etc. Perhaps these are far more sophisticated representations than we have imagined. There is another drawing at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc that cautions us against ready assumptions. It has been interpreted as depicting the thighs and genitals of a woman but there is also a drawing of a bison and a lion, and the images are nearly intertwined. In addition to the drawings, the cave is littered with the skulls and bones of cave bear and the track of a wolf. There is also a footprint thought to have been made by an eight-year-old boy.

Clovis culture

Although the Paleo-Indians who migrated to America from Asia (across the Bering Strait — a land bridge that once joined present-day Alaska and eastern Siberia) during the Pleistocene Epoch (Ice Age) did not leave behind a written (or even a large material) record, they can be identified by specific toolkits. Clovis points, for example, reveal technologies of hunting and processing meat, as well as crafting a sharp point from available resources. Workers used a hard rock to chip flakes from a softer one, shaping it into a sturdy point that could be used by hand or fastened to a wooden spear.

Clovis points from the Rummells-Maske site, Cedar County, Iowa (photo: Billwhittaker, CC BY-SA 3.0)

These tools reveal that Clovis people were hunter-gatherers, relying upon big game. As ice thawed, toolkits diversified. Later Archaic people left behind wooden fishing spears reflecting an expansion of hunting and diet, possible boat technology, and a variety of specialized stone tools. But the most significant development in the Americas was the start of agriculture which fundamentally altered lifestyles of people throughout the hemisphere.

Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Paleolithic art, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, June 8, 2018, accessed June 5, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/paleolithic-art-an-introduction/.

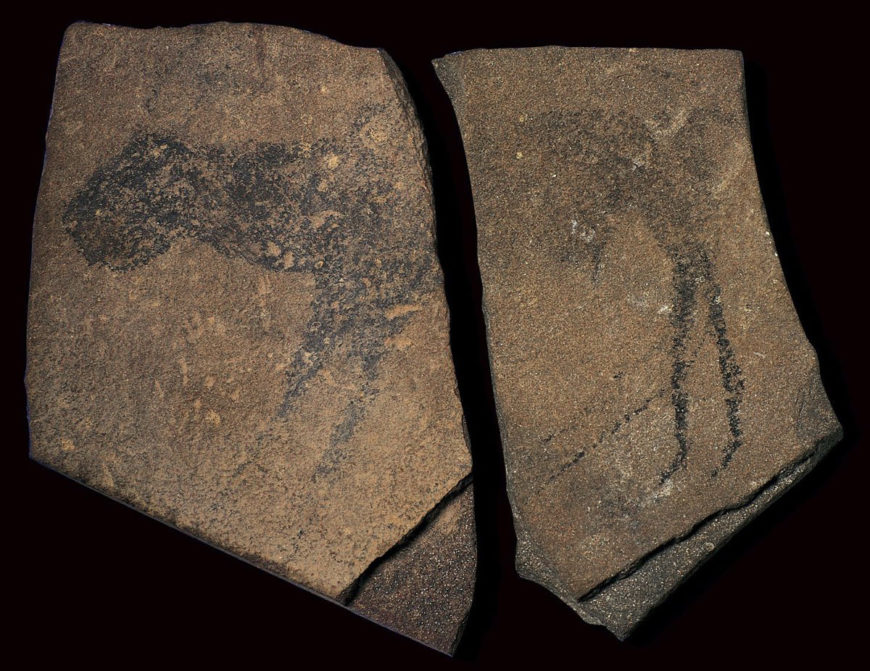

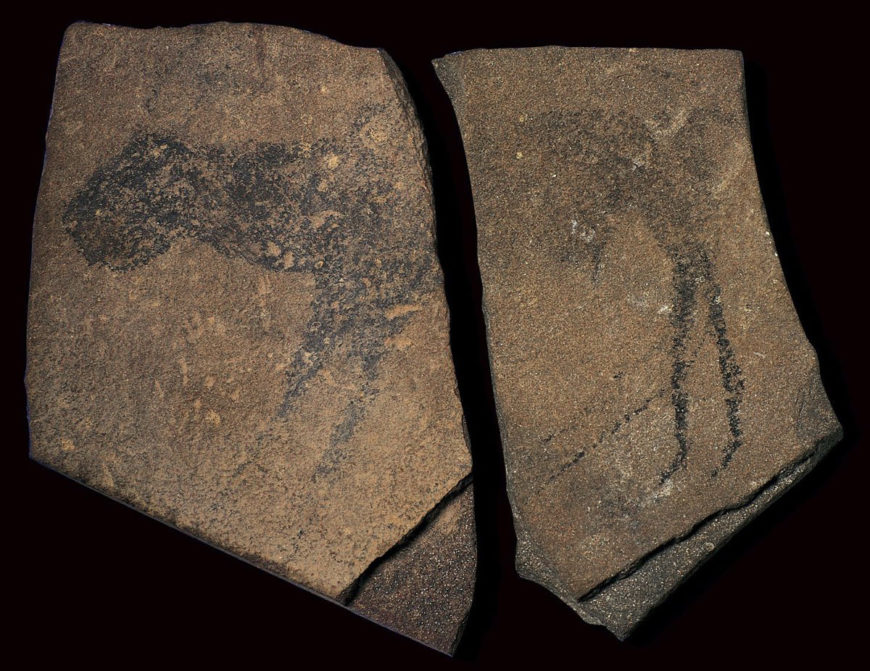

Quartzite slabs depicting animals, Apollo 11 Cave, Namibia, c. 25,500–25,300 B.C.E. Image courtesy of State Museum of Namibia, Windhoek

A significant discovery

Location of the Huns Mountains of Namibia (underlying map © Google)

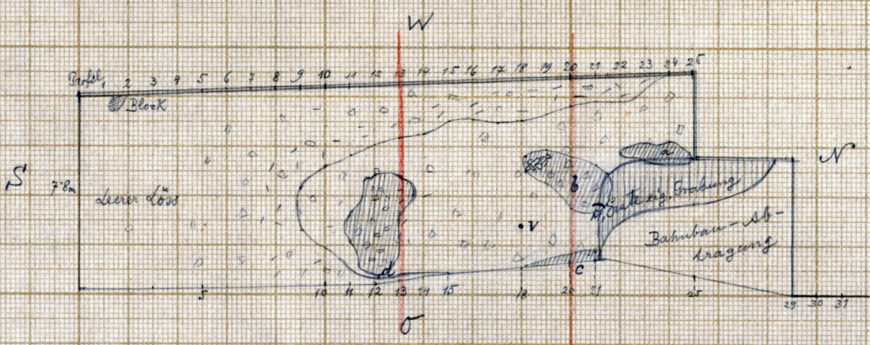

Approximately 25,000 years ago, in a rock shelter in the Huns Mountains of Namibia on the southwest coast of Africa (today part of the Ai-Ais Richtersveld Transfrontier Park), an animal was drawn in charcoal on a hand-sized slab of stone. The stone was left behind, over time becoming buried on the floor of the cave by layers of sediment and debris until 1969 when a team led by German archaeologist W.E. Wendt excavated the rock shelter and found the first fragment (the left slab of the Quartzite slabs depicting animals). Wendt named the cave “Apollo 11” upon hearing on his shortwave radio of NASA’s successful space mission to the moon. It was more than three years later however, after a subsequent excavation, when Wendt discovered the matching fragment (the right slab of the Quartzite slabs depicting animals), that archaeologists and art historians began to understand the significance of the find.

Indirect dating techniques

In total seven stone fragments of brown-grey quartzite, some of them depicting traces of animal figures drawn in charcoal, ocher, and white, were found buried in a concentrated area of the cave floor less than two meters square. While it is not possible to learn the actual date of the fragments, it is possible to estimate when the rocks were buried by radiocarbon dating the archaeological layer in which they were found. Archaeologists estimate that the cave stones were buried between 25,500 and 25,300 years ago during the Middle Stone Age period in southern Africa making them, at the time of their discovery, the oldest dated art known on the African continent and among the earliest evidence of human artistic expression worldwide.

While more recent discoveries of much older human artistic endeavors have corrected our understanding (consider the 2008 discovery of a 100,000-year-old paint workshop in the Blombos Cave on the southern coast of Africa), the stones remain the oldest examples of figurative art from the African continent. Their discovery contributes to our conception of early humanity’s creative attempts, before the invention of formal writing, to express their thoughts about the world around them.

The origins of art?

Genetic and fossil evidence tells us that Homo sapiens developed on the continent of Africa more than 100,000 years ago and spread throughout the world. But what we do not know—what we have only been able to assume—is that art, too, began in Africa. Is Africa, where humanity originated, home to the world’s oldest art? If so, can we say that art began in Africa?

View across Fish River Canyon toward the Huns Mountains, /Ai-/Ais – Richtersveld Transfrontier Park, southern Namibia (photo: Paul Keller, CC BY 2.0)

100,000 years of human occupation

The Apollo 11 rock shelter overlooks a dry gorge, sitting twenty meters above what was once a river that ran along the valley floor. The cave entrance is wide, about twenty-eight meters across, and the cave itself is deep: eleven meters from front to back. While today a person can stand upright only in the front section of the cave, during the Middle Stone Age, as well as in the periods before and after, the rock shelter was an active site of ongoing human settlement.

View of painted rock art showing a horizontal zigzag line in white with short white lines emanating from the points and some dashes of red pigment, excavation site of the Apollo 11 stones, Namibia (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London; photo: David Coulson MBE)

Inside the cave, above and below the layer where the Apollo 11 cave stones were found, archaeologists unearthed a sequence of cultural layers representing over 100,000 years of human occupation. In these layers stone artifacts, typical of the Middle Stone Age period—such as blades, pointed flakes, and scrapers—were found in raw materials not native to the region, signaling stone tool technology transported over long distances. Among the remnants of hearths, ostrich eggshell fragments bearing traces of red color were also found—either remnants of ornamental painting or evidence that the eggshells were used as containers for pigment.

On the cave walls, belonging to the Later Stone Age period, rock paintings were discovered depicting white and red zigzags, two handprints, three geometric images, and traces of color. And on the banks of the riverbed just upstream from the cave, engravings of a variety of animals, some with zigzag lines leading upwards, were found and dated to less than 2000 years ago.

Apollo 11 Cave Stones, Namibia, quartzite, c. 25,500–25,300 B.C.E. Image courtesy of State Museum of Namibia

The Apollo 11 cave stones

But the most well-known of the rock shelter’s finds, and the most enigmatic, remain the Apollo 11 cave stones. On the cleavage face of what was once a complete slab, an unidentified animal form was drawn resembling a feline in appearance but with human hind legs that were probably added later. Barely visible on the head of the animal are two slightly-curved horns likely belonging to an Oryx, a large grazing antelope; on the animal’s underbelly, possibly the sexual organ of a bovid.

Perhaps we have some kind of supernatural creature—a therianthrope, part human and part animal? If so, this may suggest a complex system of shamanistic belief. Taken together with the later rock paintings and the engravings, Apollo 11 becomes more than just a cave offering shelter from the elements. It becomes a site of ritual significance used by many over thousands of years.

The global origins of art

In the Middle Stone Age period in southern Africa, prehistoric man was a hunter-gatherer, moving from place to place in search of food and shelter. But this modern human also drew an animal form with charcoal—a form as much imagined as it was observed. This is what makes the Apollo 11 cave stones find so interesting: the stones offer evidence that Homo sapiens in the Middle Stone Age—us, some 25,000 years ago—were not only anatomically modern, but behaviorally modern as well. That is to say, these early humans possessed the new and unique capacity for modern symbolic thought, “the human capacity,” long before what was previously understood.

The cave stones are what archaeologists term art mobilier—small-scale prehistoric art that is moveable. But mobile art, and rock art generally, is not unique to Africa. Rock art is a global phenomenon that can be found across the world—in Europe, Asia, Australia, and North and South America. While we cannot know for certain what these early humans intended by the things that they made, by focusing on art as the product of humanity’s creativity and imagination we can begin to explore where, and hypothesize why, art began.

Cite this page as: Dr. Nathalie Hager, “Apollo 11 Cave Stones,” in Smarthistory, May 28, 2018, accessed June 5, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/apollo-11-cave-stones-2/.

The name of this prehistoric sculpture refers to a Roman goddess—but what did she originally represent?

The artifact known as the Venus of Willendorf dates to between 24,000–22,000 B.C.E., making it one of the oldest and most famous surviving works of art. But what does it mean to be a work of art?

The Oxford English Dictionary, perhaps the authority on the English language, defines the word “art” as

the application of skill to the arts of imitation and design, painting, engraving, sculpture, architecture; the cultivation of these in its principles, practice, and results; the skillful production of the beautiful in visible forms.

Some of the words and phrases that stand out within this definition include “application of skill,” “imitation,” and “beautiful.” By this definition, the concept of “art” involves the use of skill to create an object that contains some appreciation of aesthetics. The object is not only made, it is made with an attempt of creating something that contains elements of beauty.

In contrast, the same Oxford English Dictionary defines the word “artifact” as,

anything made by human art and workmanship; an artificial product. In Archaeol[ogy] applied to the rude products of aboriginal workmanship as distinguished from natural remains.

Again, some keywords and phrases are important: “anything made by human art,” and “rude products.” Clearly, an artifact is any object created by humankind regardless of the “skill” of its creator or the absence of “beauty.”