By the early fifth century B.C.E. the Achaemenid (Persian) Empire ruled an estimated 44% of the human population of planet Earth. Through regional administrators the Persian kings controlled a vast territory which they constantly sought to expand. Famous for monumental architecture, Persian kings established numerous monumental centers, among those is Persepolis (today, in Iran). The great audience hall of the Persian kings Darius and Xerxes presents a visual microcosm of the Achaemenid empire—making clear, through sculptural decoration, that the Persian king ruled over all of the subjugated ambassadors and vassals (who are shown bringing tribute in an endless eternal procession).

Overview of the Achaemenid Empire

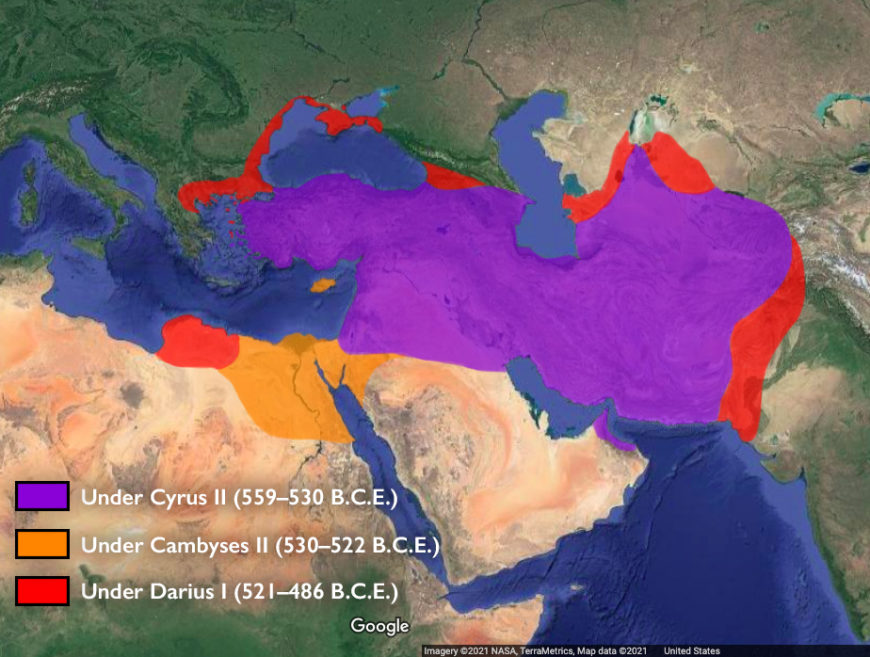

The Achaemenid Empire (First Persian Empire) was an imperial state of Western Asia founded by Cyrus the Great and flourishing from c. 550–330 B.C.E. The empire’s territory was vast, stretching from the Balkan peninsula in the west to the Indus River valley in the east. The Achaemenid Empire is notable for its strong, centralized bureaucracy that had, at its head, a king and relied upon regional satraps (regional governors).

A number of formerly independent states were made subject to the Persian Empire. These states covered a vast territory from central Asia and Afghanistan in the east to Asia Minor, Egypt, Libya, and Macedonia in the west. The Persians famously attempted to expand their empire further to include mainland Greece but they were ultimately defeated in this attempt. The Persian kings are noted for their penchant for monumental art and architecture. In creating monumental centers, including Persepolis, the Persian kings employed art and architecture to craft messages that helped to reinforce their claims to power and depict, iconographically, Persian rule.

Overview of Persepolis

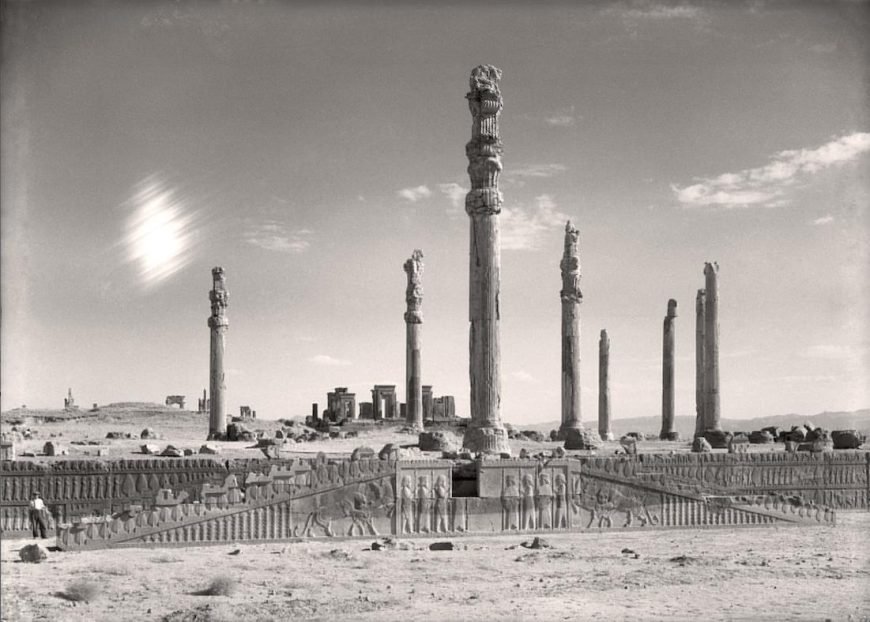

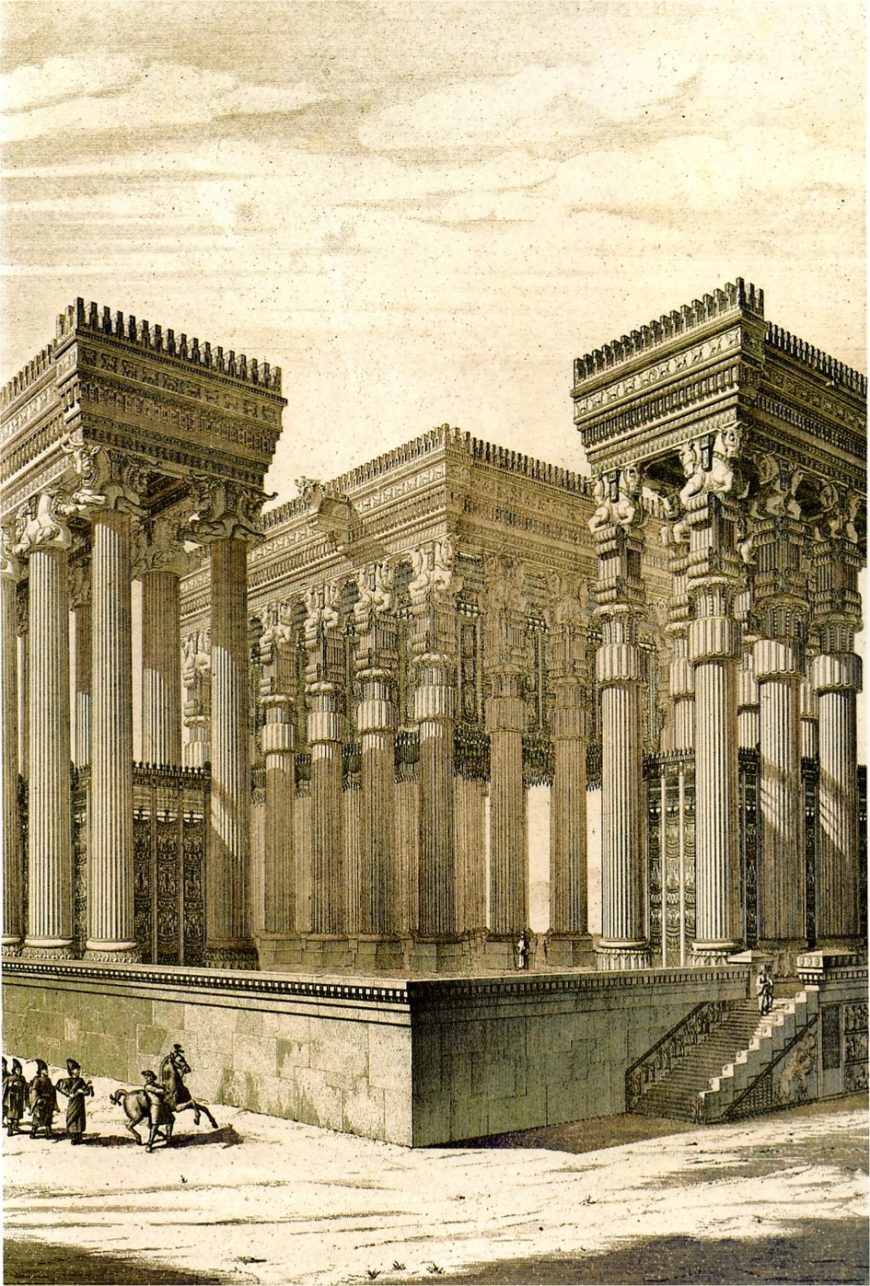

Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Persian empire, lies some 60 km northeast of Shiraz, Iran. The earliest archaeological remains of the city date to c. 515 B.C.E. Persepolis, a Greek toponym meaning “city of the Persians”, was known to the Persians as Pārsa and was an important city of the ancient world, renowned for its monumental art and architecture. The site was excavated by German archaeologists Ernst Herzfeld, Friedrich Krefter, and Erich Schmidt between 1931 and 1939. Its remains are striking even today, leading UNESCO to register the site as a World Heritage Site in 1979.

Persepolis was intentionally founded in the Marvdašt Plain during the later part of the sixth century B.C.E. It was marked as a special site by Darius the Great in 518 B.C.E. when he indicated the location of a “Royal Hill” that would serve as a ceremonial center and citadel for the city. This was an action on Darius’ part that was similar to the earlier king Cyrus the Great who had founded the city of Pasargadae. Darius the Great directed a massive building program at Persepolis that would continue under his successors Xerxes and Artaxerxes I. Persepolis would remain an important site until it was sacked, looted, and burned under Alexander the Great of Macedon in 330 B.C.E.

Darius’ program at Persepolis including the building of a massive terraced platform covering 125,000 square meters of the promontory. This platform supported four groups of structures: residential quarters, a treasury, ceremonial palaces, and fortifications. Scholars continue to debate the purpose and nature of the site. Primary sources indicate that Darius saw himself building an important stronghold. Some scholars suggest that the site has a sacred connection to the god Mithra (Mehr), as well as links to the Nowruz, the Persian New Year’s festival. More general readings see Persepolis as an important administrative and economic center of the Persian empire.

Apādana

The Apādana palace is a large ceremonial building, likely an audience hall with an associated portico. The audience hall itself is hypostyle in its plan, meaning that the roof of the structure is supported by columns. Apādana is the Persian term equivalent to the Greek hypostyle (Ancient Greek: ὑπόστυλος hypóstȳlos). The footprint of the Apādana is c. 1,000 square meters; originally 72 columns, each standing to a height of 24 meters, supported the roof (only 14 columns remain standing today). The column capitals assumed the form of either twin-headed bulls (above), eagles or lions, all animals represented royal authority and kingship.

The king of the Achaemenid Persian empire is presumed to have received guests and tribute in this soaring, imposing space. To that end a sculptural program decorates monumental stairways on the north and east. The theme of that program is one that pays tribute to the Persian king himself as it depicts representatives of 23 subject nations bearing gifts to the king.

The Apādana stairs and sculptural program

The monumental stairways that approach the Apādana from the north and the east were adorned with registers of relief sculpture that depicted representatives of the twenty-three subject nations of the Persian empire bringing valuable gifts as tribute to the king. The sculptures form a processional scene, leading some scholars to conclude that the reliefs capture the scene of actual, annual tribute processions—perhaps on the occasion of the Persian New Year–that took place at Persepolis. The relief program of the northern stairway was perhaps completed c. 500–490 B.C.E. The two sets of stairway reliefs mirror and complement each other. Each program has a central scene of the enthroned king flanked by his attendants and guards.

Noblemen wearing elite outfits and military apparel are also present. The representatives of the twenty-three nations, each led by an attendant, bring tribute while dressed in costumes suggestive of their land of origin. Margaret Root interprets the central scenes of the enthroned king as the focal point of the overall composition, perhaps even reflecting events that took place within the Apādana itself.

The relief program of the Apādana serves to reinforce and underscore the power of the Persian king and the breadth of his dominion. The motif of subjugated peoples contributing their wealth to the empire’s central authority serves to visually cement this political dominance. These processional scenes may have exerted influence beyond the Persian sphere, as some scholars have discussed the possibility that Persian relief sculpture from Persepolis may have influenced Athenian sculptors of the fifth century B.C.E. who were tasked with creating the Ionic frieze of the Parthenon in Athens. In any case, the Apādana, both as a building and as an ideological tableau, make clear and strong statements about the authority of the Persian king and present a visually unified idea of the immense Achaemenid empire.

UNESCO video on Persepolis

Persepolis on Livius.org

Persepolis relief in the British Museum

Persepolis from the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago

John Boardman, Persia and the West: an archaeological investigation of the genesis of Achaemenid art (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000).

John Curtis, Nigel Tallis, and Béatrice André-Salvini, Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

John Curtis, The world of Achaemenid Persia: history, art and society in Iran and the ancient Near East: proceedings of a conference at the British Museum, 29th September–1st October 2005 (London: I. B. Tauris, 2010).

R. Schmitt and D. Stronach, “Apadana,” Encyclopædia Iranica, II/2, pp. 145–48.

A. Shapur Shahbazi, “Persepolis,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2010.

Wolfram Kleiss, “Zur Entwicklung der achaemenidischen Palastarchitektur,” AMI, volume 14 (1981), pp. 199–211.

Margaret Cool Root, “The king and kingship in Achaemenid art: essays on the creation of an iconography of empire,” Acta Iranica, volume 19 (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1979).

Margaret Cool Root, “The Parthenon Frieze and the Apadana Reliefs at Persepolis: Reassessing a Programmatic Relationship,” American Journal of Archaeology, volume 89, number 1 (1985), pp. 103–22.

Erich Friedrich Schmidt, Persepolis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953–1970).

R. Schmitt, “Achaemenid Dynasty,” Encyclopædia Iranica, I/4, pp. 414–26.

A. S. Shahbazi, “The Persepolis “Treasury Reliefs’ Once More,” AMI, volume 9 (1976) pp. 151–56.

Robert E. Mortimer Wheeler, Flames over Persepolis: Turning Point in History (London, 1968).

Cite this page as: Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker, “Persepolis: The Audience Hall of Darius and Xerxes,” in Smarthistory, January 24, 2016, accessed March 25, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/persepolis-the-audience-hall-of-darius-and-xerxes/.