Hypostyle hall, Great Mosque-Cathedral at Córdoba, Spain, begun 786 and enlarged during the 9th and 10th centuries (photo: wsifrancis, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Strait of Gibraltar, a narrow waterway that runs between Spain and Portugal to the north and Morocco to the south, separates Europe from Africa (see map below). Although water divides the two continents, the strait has served as a bridge—and has encouraged lively exchange and dynamic interaction throughout the region. We tend to think of bridges as physical structures that help to guide people over an obstacle such as a body of water, but by looking at the history of the region, especially in terms of art and architecture, we can see that the Strait of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean Sea actually served to unify, and were instrumental in shaping the people, cultures, and histories of adjacent regions on two continents.

This essay provides an overview of the art and architecture of the Islamic West, a term that refers to the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal today) when it was under Islamic rule, and what is today Morocco in northwest Africa. Not only will we look at art and architecture that was produced by Muslims, but we will also explore striking examples of visual culture from Iberia’s Jewish and Christian communities, work that highlights the rich diversity and multiculturalism of medieval Iberia. Examples drawn from different dynasties demonstrate the remarkable degree of cultural exchange and interaction that flourished there.

Constructing an Islamic Identity

The victory of Muslim forces against the Visigoths at the Battle of Guadalete in 711 marked a new era in the history of the Iberian Peninsula. In the centuries that followed, the Islamic presence in the Iberian Peninsula, particularly its southern reaches, increased considerably.

In 755, the Umayyad dynasty was reestablished on the Iberian Peninsula (when the last surviving member of the family fled west after the triumph of the Abbasid caliphate).

Although it predates the Umayyads, the city of Córdoba (in what is now southern Spain) developed rapidly under the dynasty as one of its capital cities. Both Córdoba and its surroundings boast incredible monuments that shed light on the visual cultures of early Islamic Iberia, a period when the Islamic presence in the region was rapidly growing, and there was an effort to establish a coherent and shared sense of identity in this new land.

Great Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain, begun 786, cathedral in the center added 16th century (photo: Toni Castillo Quero, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba in the city’s urban center and Madinat al-Zahra, a palatial complex outside of the city in the countryside, are two important sites of early Islamic Iberia. While the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba is more frequently discussed, Madinat al-Zahra is worth considering in detail. It does not always get the same attention as other monuments in and around the city because it lies mostly in ruins and has been the subject of ongoing archaeological excavations.

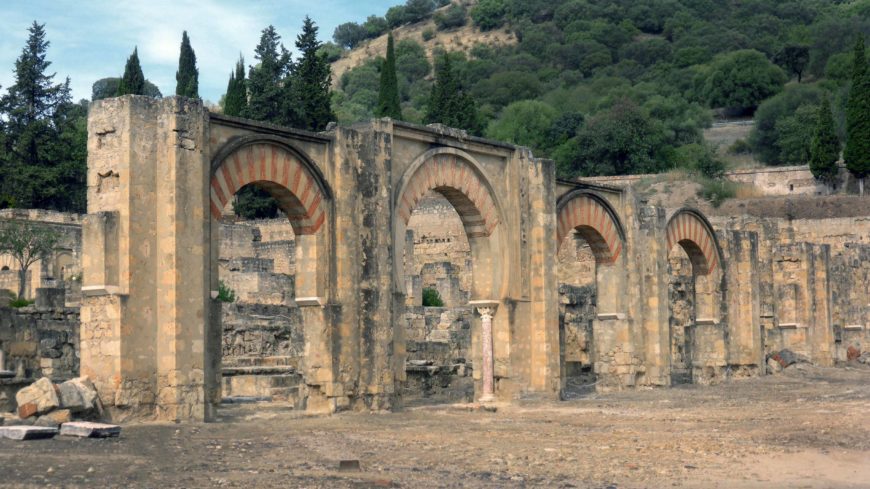

Madinat al-Zahra, mid 10th century, Córdoba, Spain (photo: David Abián, CC BY-SA 3.0 ES)

Madinat al-Zahra

Madinat al-Zahra serves as a great example of monumental art and architecture in al-Andalus (the term used to refer to the parts of Iberia under Islamic rule). Its components reflect connections and continuity with both the Roman and Visigothic heritage in this area, as well as the Islamic and Byzantine heritage of the eastern Mediterranean. Madinat al-Zahra was built by the 10th-century ruler Abd al-Rahman III who proclaimed an Umayyad caliphate in Iberia. Although Abd al-Rahman III began the construction of the palatial complex, his successor al-Hakam II continued to modify and add to it.

The palace complex consists of numerous buildings, including reception halls, mosques, homes, kitchens, and more, constructed over an expansive terraced landscape. The highest terrace was reserved for the caliph, his family, and members of the royal administration. The second terrace featured gardens, pools, and orchards. The third and lowest layer was the most public-facing and inclusive, featuring mosques, markets, military quarters, and more.

Salón Rico, Madinat al-Zahra, Córdoba, Spain (photo: Zarateman, CC BY-SA 3.0 ES)

One of the highlights of Madinat al-Zahra was the Salón Rico, which was centrally located on the second terrace. It was a reception room for the caliph to meet and entertain foreign political delegations. The room is structured by two rows of horseshoe arches, three aisles, and an ornamental wall at one end. The marble used in much of the complex, including Salón Rico, was sourced from the Estremoz quarries in Portugal. The style of the components in this space, such as the use of acanthus leaves on the capitals, point to a reliance on Late Antique visual traditions.

Horseshoe arches at the North Gate, Madinat al-Zahra, Córdoba, Spain (photo: Jeroen van Luin, CC BY 2.0)

Voussoirs, detail of the horseshoe arches at the North Gate, Madinat al-Zahra, Córdoba, Spain (photo: Francisco Jesus Ibañez, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Horseshoe arches, which appear widely throughout the Iberian Peninsula, are thought to have been developed under the Visigoths, while the alternating colored stones on the arches can be found in Umayyad architecture on the eastern side of the Mediterranean at sites such as the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. The alternating red-and-white voussoirs on the horseshoe arches are a striking feature at Madinat al-Zahra, and they can also be found on the arches at the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba and elsewhere.

Capital from Madinat al-Zahra, Córdoba, Spain (Archaeological Museum, Madinat al-Zahra; photo: Ángel M. Felicísimo, CC BY 2.0)

Vegetal patterns found on column capitals at Madinat al-Zahra are reminiscent of the artistic heritage of Islamic art and architecture of the eastern Mediterranean as well, particularly in Syria, when it was under the rule of the Umayyads.

These various elements demonstrate the extent to which the visual heritage of early Islamic Iberia was a conglomeration of elements drawn from a variety of distinct places and eras. Ultimately, Madinat al-Zahra was destroyed during a revolt in the early eleventh century, a time when Umayyad power had waned.

Pyxis of al-Mughira, possibly from Madinat al-Zahra (Córdoba, Spain), AH 357/968 CE, carved ivory with traces of jade, 16cm x 11.8 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

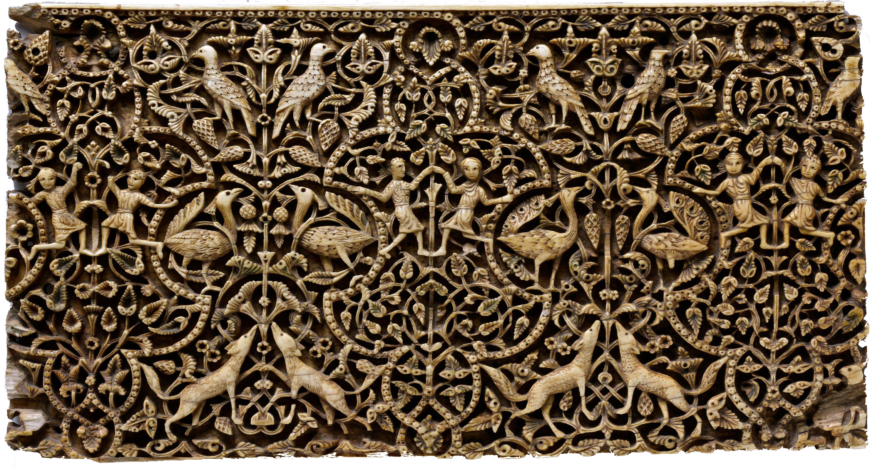

Portable art objects, including a number of ivory containers, express the luxurious aspects of life under the Umayyads as well as the connections that the Iberian Umayyads maintained with their heritage in the eastern Mediterranean. These containers, which are often highly ornamented with vegetal decoration and Arabic calligraphy, are called pyxides (plural), and they would have held anything from perfumes to relics.

Panel from a rectangular box, 10th–early 11th century, ivory with traces of pigment, made in Spain, probably Córdoba, 10.8 cm x 20.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A panel of a pyxis, made out of a solid piece of elephant ivory, is intricately carved and would have required a set skilled of craftspeople and painstaking effort to design and produce it. Many of these containers still exist, along with other similar luxury goods from medieval Iberia, so there was clearly a market for such work, one that crossed identity lines. The prevalence of luxuries such as the pyxis, demonstrates how art traveled widely beyond religious and political lines. Pyxides were coveted by people outside of the Islamic context. The pyxides that were produced under the Muslims were valued and often taken as booty. They were presented and became reliquaries in Christian contexts.

La Aljafería, Saragossa, Span (photo: FRANCIS RAHER, CC BY 2.0)

Competing Identities

After the fall of the Umayyads of al-Andalus, Iberia saw the rise of Taifa/Party Kingdoms. These kingdoms arose in the eleventh century in the political vacuum created by the collapse of the Umayyad state in Córdoba. These rival kingdoms were independently governed city-states and often competed with one another militarily and in terms of cultural production. One of these city-states was located in Saragossa, and its palace is a stunning example of the artistic developments of Islamic visual culture on the Iberian Peninsula.

The Aljafería Palace has numerous arches (much like the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba and Madinat al-Zahra), but the decorative elements are striking and represent a notable departure from earlier centuries. For example, stucco, which is known as yesería, appears as complex vegetal and floral motifs. Stucco was less commonly found in the visual culture of the Umayyads of the Islamic West, though the motifs themselves were commonplace.

Stucco decoration was also an integral part of the artistic toolkit of the Mudéjar populations (Muslims living under Christian rule on the Iberian Peninsula), and these decorations reached their pinnacle under the Nasrids. Many examples of these stucco decorations can also be found at the Alhambra.

Despite the early strength of Islamic rule on the Iberian Peninsula, the declaration of a caliphate, the tolerance of limited multiculturalism—within a religious and social hierarchy—and the pressure of the Reconquista from the Catholic north led to a reversal of fortune for the Muslims of al-Andalus.

Before the Reconquista was completed in 1492, two powerful dynasties emerged in Morocco that served as a countervailing force against the military pressure exerted by Christians in the north. The Almoravids and the Almohads, each eventually conquered parts of the Iberian Peninsula and delayed the Christian reconquest. The visual cultures of these dynasties, each originating in Morocco, are worth keeping in mind since they both constructed architectural monuments in North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula—creating a cohesive architectural heritage spanning the Strait of Gibraltar.

Minaret of the Tin Mal Mosque, Morocco (photo: Migeo53, CC BY-SA 4.0)

One Almohad monument worth considering is a mosque called Tin Mal, situated in the High Atlas Mountains. The minaret of the mosque is striking, as it takes a quadrangular form as opposed to a rounded one, echoing other minarets and towers erected by the Almohad dynasty.

Tin Mal Mosque, Morocco (photo: Alexander Leisser, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Although the interior features vegetal patterns, the exterior façade of the mosque is generally devoid of decorative features, reflecting the sobriety of many monuments produced by the Almohads due to their ideological notions of religious and social purification.

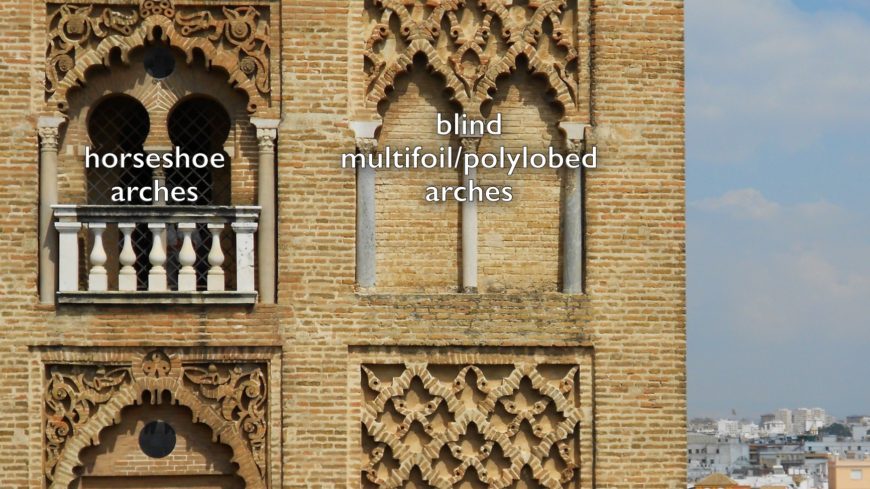

Two minarets, La Giralda in Seville (part of the Great Mosque of Seville under the Almohads) and the tower of the Qutubiyya Mosque (also spelled Koutoubiya) in Marrakesh, were both constructed under the Almohads. Both are tall rectangular towers strikingly similar to their counterpart at Tin Mal. The surface decoration found on La Giralda is intricate and worth observing, particularly because much of it has survived since the original construction.

Multifoil/polylobed arches, Tower (Giralda), Seville Cathedral, Seville, Spain (photo: Naroa, CC BY-NC 2.0)

This surface poses a striking visual contrast between smooth and uninterrupted stone in much of the lower part of the tower and blind multifoil/polylobed arches as well as horseshoe arches, some of which are set on marble columns. Meanwhile, the minaret of the Qutubiyya features similar components, including the blind arches.

Qutubiyya (Koutoubiya) Mosque, Marrakesh, Morocco (photo: Daniel Csörföly, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Both of these minarets reflect the continuity in visual culture across the Strait of Gibraltar. At the same time, they also reflect the subsequent histories of each region. While La Giralda was converted into a bell tower for Seville’s cathedral after the Reconquest, the tower at the Qutubiyya Mosque in Marrakesh remains a minaret for a vibrant central mosque to this day. While bells toll from La Giralda, the Islamic call to prayer can be heard from the Qutubiyya’s minaret. While time and historical circumstance has altered the function of one of these towers, their shared visual heritage remains unmistakable.

Ten-dinar coin, 1248–66, Rabat, Morocco (Numismatic Museum of the al-Maghreb Bank)

Almohad coins, also known as masmudia, are another important art form of medieval Iberia. Like pyxides, they were desirable outside of their Islamic context and also circulated in Christian-controlled northern Iberia, likely for reasons of prestige. A ten-dinar coin made in Morocco was modified so that it could be worn as jewelry (see above). One side of the coin features the Islamic declaration of faith (basmala) as well as the name of the prince under whom the coin was issued and that of his father, while the other side of the coin states the names of important Almohad leaders.

The use of a simple square, containing and surrounded by calligraphy, and minimal additional embellishment align with the strict religious outlook and vision of the Almohads. The Almohads tried to streamline the practice of Islam on the Iberian Peninsula, and their political actions, texts, and visual culture testify to this fact.

Horseshoe-arched colonnade, San Miguel de Escalada, 10th century, Spain (photo: David Perez, CC BY 3.0)

Locating Religious Diversity

In addition to the many Muslims who lived in the Iberian Peninsula after its conquest in the early eighth century, Christians and Jews made important contributions to the development of the art and architecture of the Peninsula. San Miguel de Escalada, a Christian monastery in northern Iberia, was constructed in the tenth century by monks who fled Córdoba after the Islamic conquest of the city. Although San Miguel de Escalada was constructed in a region controlled by Christians, it is considered Mozarabic because the monks responsible for its reconstruction had come from Córdoba. Elements of the monastery clearly reflect aspects of the Islamic art of al-Andalus, even though this was explicitly constructed as a Christian religious space. For example, the monastery’s interior and exterior feature rows of horseshoe arches, much like those at Madinat al-Zahra. Yet its interior structure features elements such as an apse and a nave, which are central components of Christian church architecture in the Iberian Peninsula and more broadly. Many of the columns found on this site are Roman spolia, which demonstrates the incorporation of earlier visual heritage.

Textile fragment from the Tomb of Don Felipe, second half 13th century, from Palencia, Spain, silk, linen, metal-wrapped thread; taqueté, H. 48.6cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Artistic patronage could transcend religious and/or cultural lines. A textile fragment found buried in a tomb of Don Felipe Infante (who died in 1274 and was son of Ferdinand II and brother of Alfonso X, both thirteenth-century Christian kings of Castile) features floral patterns such as rosettes and Arabic writing in a calligraphic script known as kufic. Like the coin discussed earlier, this textile fragment demonstrates how artistic styles and language were valued across religious and cultural lines, even during, and maybe as a result of, socio-political tensions.

Samuel Halevi Abulafia synagogue, c. 1360, Toledo, Spain (photo: Antonio.velez, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Jewish communities were also integral to the diverse culture of al-Andalus. The Ibn Shoshan Synagogue (renamed Santa María la Blanca when it was converted into a church) and the synagogue of El Tránsito in the city of Toledo both demonstrate this diversity beautifully. While the former was constructed in the twelfth century during the Almohad era, the latter was constructed in the fourteenth century after the Reconquista had already brought Toledo under the rule of Catholics, in this case under Peter of Castile, who was known as Peter the Cruel.

Both synagogues feature stucco, which was now a prominent building and decorative material in architectural structures throughout the region, regardless of religious or cultural affiliation. They also consist of multiple naves divided by arches. The Ibn Shoshan Synagogue (now more commonly known by the church’s name) was built by Mudéjar craftsmen, who used yesería decoration heavily. Like many mosques, synagogues were also often converted to churches after the Reconquista.

The Castilian synagogues (such as Santa María la Blanca) of the thirteenth century tend to be similar to mosques architecturally. Jews who left al-Andalus and moved north likely brought these building traditions with them. This synagogue has five naves, and the central nave is slightly wider than the other four. A unique feature of the synagogue was likely the Hekhál—also known as the Torah ark to house the scrolls of the Torah—which is unfortunately no longer extant. In contrast, El Tránsito follows a distinct pattern of organization, featuring a large open space rather than space divided by naves. This synagogue combines elements from both Islamic and Christian artistic traditions, such as vegetal patterns from the former and a coat of arms from the latter (this coat of arms was attributed to the Halevi family, an important Jewish family of Iberia).

In spite of the rich legacy of Jews on the Iberian Peninsula, their prospects turned grim as the centuries progressed with political enactments, forced conversions, and massacres characterizing the Jewish experience in Iberia in the fourteenth century.

Alhambra, Granada, Spain (photo: Ajay Suresh, CC BY 2.0)

Visual Culture in an Era of Constriction

The Nasrids were the last Islamic dynasty in al-Andalus. While the Alhambra is the most well-known structure of this dynasty, domestic spaces of a less public nature reveal how people, just below the highest social classes, lived their day-to-day lives. Daily routines can be imagined in a wholly different way through these somewhat more modest domestic spaces.

Zafra House in the Albaycín neighborhood, Granada, Spain (photo: Øyvind Holmstad, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Albaycín neighborhood in Granada, which overlooks the Alhambra, demonstrates how elite classes in al-Andalus lived. In particular, the Zafra House in Albaycín has a central courtyard that is surrounded by rooms and consists of three floors. Each side of the patio on the ground floor has a portico, and each portico has marble columns and capitals with arches. In addition to the ground floor, there are two additional galleries above the porticos on the ground floor that span the same length as the porticos. This layered internal space is revealed to visitors upon entry without the slightest hint of this complexity revealed from the external façade. This outward homogeneity, in a way, maintained a heightened sense of privacy about how individuals carried on their daily lives. The external plainness, in contrast with the internal complexity in terms of organization, is an element of domestic architecture from many other parts of the Islamic world and demonstrates the extent of architectural continuities across geographies that were inspired by a shared religious tradition and social ethos.

The Nasrids ruled during a period of increasing constriction for the Muslims and Jews of Iberia. By the thirteenth century, when the Nasrids came to power in southern Iberia, the borders of al-Andalus looked very different from the early centuries when Islamic power extended into the northernmost reaches of the Iberian Peninsula. The Reconquista had been driving southward, strengthened by alliances among Catholic monarchs as well as the support of the papacy in light of the broader framework of the Crusades. During the Nasrids’ rule, all that remained of al-Andalus was the Kingdom of Granada. Not only did the Reconquista take lands that had been under Islamic rule for hundreds of years, but it also sought to suppress non-Catholic identities through inquisitorial tribunals (first established in 1487 under Ferdinand and Isabel), political decrees, and violence, which were directed towards Muslims, Jews, and anyone outside the fold of mainstream Catholicism (as defined by Spain’s religious and political leadership and also, more broadly, the papacy in Rome under the backdrop of the Crusades).

Deep Dish, c. 1430, tin-glazed earthenware, made in probably Manises, Valencia, Spain, 6 x 45.1 cm (The Cloisters)

Despite these socio-political constraints, visual culture continued to prosper. Lusterware, a type of pottery that earns its name from its lustrous sheen, was common at this time. Artists who produce lusterware finish their pieces with the application of metallic glazes, a technique refined in the Umayyad and Abbasid eras. The oxidation of these glazes results in a gorgeous iridescence. A deep dish from The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York shows a palm tree in the middle of the plate with Arabic calligraphy surrounding it. Lusterware was exported throughout Iberia and abroad. People continued to value what they could see, hold, and have, despite political dynamics. Moriscos were actively involved in the production of lusterware on the Iberian Peninsula, and evidence of lusterware from Iberia in the Americas speaks to the movement of exiled populations across the Atlantic.

These buildings and works of art demonstrate a remarkable degree of cultural exchange and interaction that flourished in the western Mediterranean in the medieval era. Political realities seldom matched up with the patronage and production of art and architecture. Exchange and interaction did not stop on the coasts of Europe or Africa either, but rather flourished across the Strait of Gibraltar, a bridge that has long served to connect people, ideas, and objects. Even in contemporary times, artists and artisans continue to produce art inspired by the historical art of Islamic Iberia.

At the same time, the rich history of Iberia demonstrates that it was also equally complex and dark. While many individuals of Jewish background, for example, rose to high professional positions, complete and utter equality was an unrealized aspiration, given the value placed on religious hierarchy and stratification as articulated by the Pact of Umar (an early Islamic document). In its time, al-Andalus posed an example of the possibilities of religious tolerance, diversity, and coexistence, but it also showcased its limitations.

Additional resources:

Read more about the Arts of the Islamic world: The early period

Read an introduction to mosque architecture

Read about the Great Mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia

Jerrilyn Dodds et al., eds. Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992)

Cities and Gardens of Muslim Spain — Dumbarton Oaks

Discover Islamic Art Virtual Exhibitions | The Muslim West

Hispano-Islamic Art at the Hispanic Society of America

Ornament of the World (film)

Jerrilynn D. Dodds, María Rosa Menocal, and Abigail Krasner Balbale, The Arts of Intimacy. Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Making of Castilian Culture (Yale University Press, 2009).

Jonathan M. Bloom, Architecture of the Islamic West, North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700–1800 (Yale University Press, 2020).

Susana Calvo Capilla, “The Reuse of Classical Antiquity in the Palace of Madinat al-Zahra’ and its Role in the Construction of Caliphal Legitimacy,” Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Cultures of the Islamic World, vol. 31 (2014), pp. 1–33.

D. Fairchild Ruggles, Islamic Gardens and Landscapes (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008).

Cite this page as: Dr. Sabahat Adil, “The vibrant visual cultures of the Islamic West, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, January 7, 2021, accessed May 14, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/islamic-west-introduction/.