Themes in Aegean Art

Themes in Aegean Art

The following articles were adapted from: https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/reframing-aegean-art/

Cite this article as: Dr. Senta German, “With and Without Homer: Reframing Aegean Art,” in Reframing Art History, Smarthistory, March 18, 2022, https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/reframing-aegean-art/.

Homer

The epic stories of the Iliad and Odyssey present the decade-long war between mythical Greeks and Trojans and its messy aftermath. The war is ignited by the kidnapping of the Greek queen Helen by the Trojan prince Paris. The conflict is then cruelly manipulated by the Olympian gods who each selfishly take a side. Great kings from both lands (Agamemnon, Odysseus, Nestor and Priam, among others) battle ferociously with their kinsmen before the walls of the city of Troy until, through the trickery of a great hollow wooden horse, the Greeks are able to breach the city gates and slaughter or enslave the population of the city. All the Greek heroes return home laden with treasure, except Odysseus, who is tormented by vengeful Poseidon, God of the sea and supporter of the Trojans, and prevented from reaching his home for another decade.

Were the kingdoms and characters of the mythic past described in the Iliad and the Odyssey real? The study of the art of the Bronze Age Aegean developed out of attempts to answer this very question. It is estimated that the epic poems of the Iliad and Odyssey were first written down in the 8th century B.C.E. by Homer but they were composed much earlier and passed on orally. Despite the poems’ long lived popularity, from ancient Greece down to our own era, key facts about the original version(s) of Homer’s works, when they were composed, where, by whom, and if they are based on any real events and/or people are largely unknown. What we do know is that those who preceded the people of the Greek Iron Age (1100–800 B.C.E.), who were the inspiration for the epics, were the cultures of the Bronze Age.

The cultures of the Bronze Age Aegean (in the 3rd and 2nd millennium) are known as

- Cycladic (on the islands of the Cyclades in the Aegean Sea)

- Minoan (on the island of Crete)

- Mycenaean (on the Mainland of Greece).

These three groups are traditionally treated by art historians separately and this is because of the history of the study of these regions and groups. In fact, while the people who lived on the Cycladic islands, Crete, and the Greek mainland each had unique visual traditions, they were also in very close contact and their visual traditions influenced each other, sometimes extensively. This chapter takes a more thematic approach, highlighting these influences and attempting to take a pan-Aegean view.

When we look at Aegean art, sometimes we see it through a Homeric lens—citadels, palaces, rich tombs and gold, a world of elite men, and mythological drama. Other times we see cultures that produced sophisticated sculpture and pottery, with elaborate theocratic economic systems, vast networks to extract raw materials, and enslaved people to produce valuable trade goods—all similar to the adjacent Near Eastern or Egyptian cultures of this time but different from the world we see in Homer. Both visions cannot be true at the same time, and Aegean scholars struggle to consolidate a coherent interpretation of all the available evidence.

With or without Homer, the way we have looked at Aegean art has been stubbornly focused on the elite—be it elite economic and political leaders or Homeric heroes. In this chapter, women and non-elite people are discussed in the context of Aegean Art, revealing that if you look from a different angle, this important part of the story can not only be found in Aegean art but also turns out to be central to Bronze Age Aegean production and consumption. Lastly, focusing on different aspects of elite architectural centers (Minoan palaces and Mycenaean citadels) we can see them as places of participatory ritual, populated by non-elite and far more than simply buildings where kings were enthroned.

Women

Women

At the beginning of the Bronze Age (c. 3200 B.C.E.), the art made on the islands of the Cyclades was both unique and vastly more sophisticated than anything found on the Mainland of Greece or Crete. Elegant figurines and delicate vessels were made from sparkling white island marble. Best known and admired of this art are the figurines, and in this tradition the representation of women is crucially important. The overwhelming majority of Cycladic figurines represent women—nude, posed with their arms folded, toes pointed, facing ahead, rendered in a radically abstracted style. Despite the proliferation of female sculptures, a disproportionate amount of attention has been paid to the very few male examples of the type (presumably because they are often represented sitting or engaged in activity).

It is a remarkable fact that there has been so little discussion about the nearly all-female aspect of Cycladic sculpture. Admittedly, because of looting in response to the very high market value of Cycladic figurines, they are frustratingly without archaeological context. Despite this, however, it is rather clear that women—mortal or otherwise—were held in high esteem at the time.

Recent research on a subset of these female Cycladic figurines, those which are quite large (over 70cm high), argues that they were used in public veneration and processions, possibly associated with the earliest regional political network in the Aegean, a confederacy centered on the island of Keros. If this is the case, we see the sculptural representation of women in the Early Bronze Age as powerful political and social symbols, with no known male sculptural competitors.

Images of women proliferate again hundreds of years later on the island of Crete among the Minoans, as well as on the Greek Mainland among the Mycenaeans. Like their male counterparts they are represented with little variation, nearly always young, dark haired, with a tiny waist, large hips, exposed breasts, and dressed in a variety of long rich and colorful garments. In wall painting, they are central actors and often focal points in complex narratives (though we don’t know what the stories are!).

In sculpture, they strike dramatic and authoritative poses, toasting, with arms raised or holding their breasts.

Unquestionably, these are important women, likely mythic or religious characters, goddesses or their attendants busy with ritual. This seems especially clear on the Hagia Triada sarcophagus, a large painted coffin featuring many women in ritual procession and carrying out sacrifices.

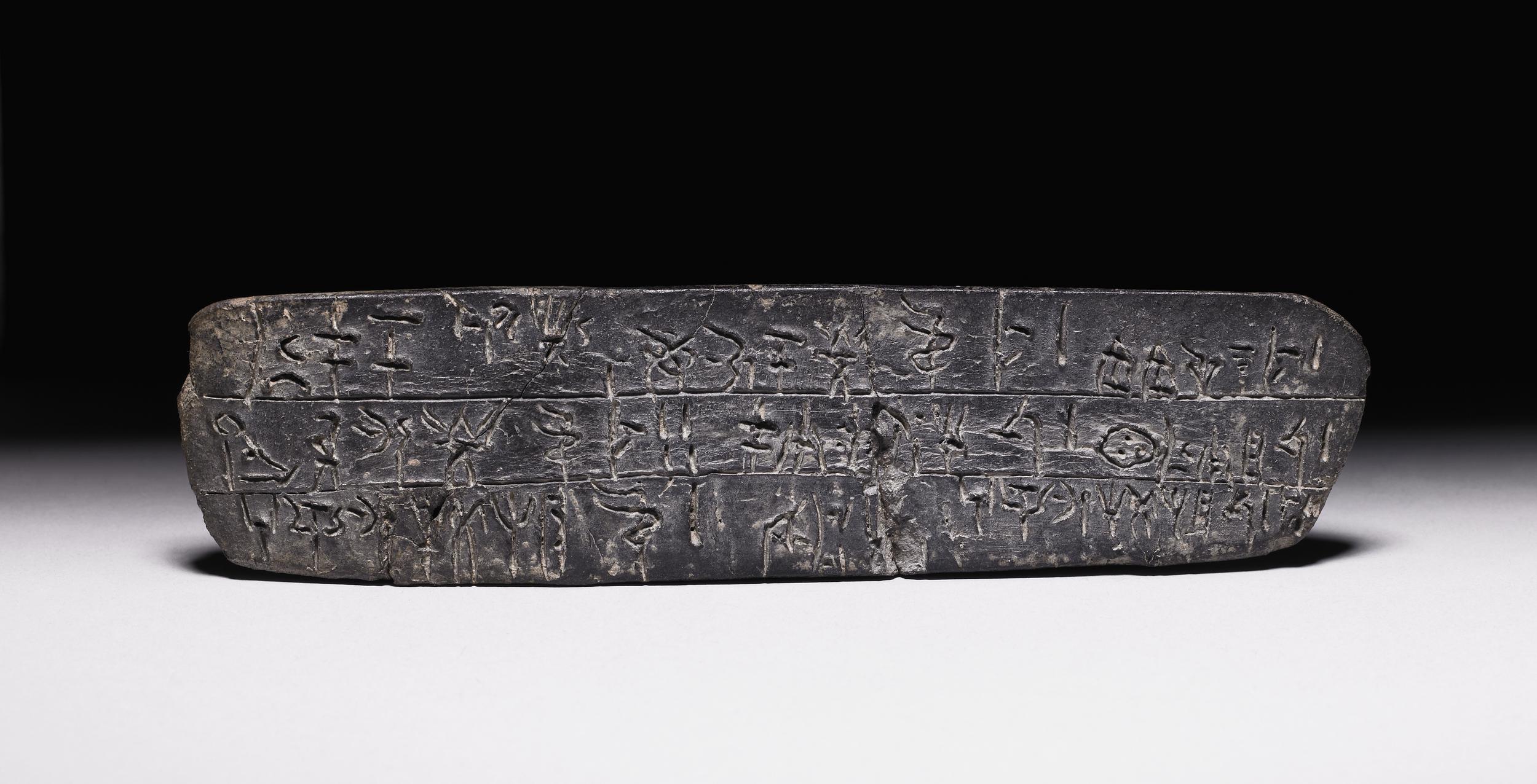

What the primary sources tell us about women

What can the central role for women in the art of the Aegean mean? It is very hard to say, however written evidence, Linear B tablets, found in the ruins of the Mycenaean palaces of Pylos and Knossos (and elsewhere) offer a lot of information about important female priestesses. A total of 120 women are identified as religious functionaries in the tablets from Pylos, all either holding land, having access to bronze, receiving textiles and other goods for use in a cult or for themselves personally, supervising low and mid-ranked personnel, and owning slaves (male and female). In fact, a rather detailed story about one such priestess, Eritha, survives.

Tablet about Eritha from Pylos: a primary source

“Eritha the priestess has a leased plot of communal land from the damos, so much seed: wheat. Eritha the priestess has and claims a freehold holding for her god, but the damos says that she holds a leased plot of communal land, so much seed: wheat.”

Linear B Tablet PY Ep 704

On the tablet from Pylos, we learn that Eritha refuses to pay tax on profit from a large tract of land she holds (no doubt cultivated by a group of her laborers) to the local leaders, the Damos, because she says she holds it on behalf of the goddess (named Potnia) and therefore is freed of this obligation.

From this one tablet we learn so much: some female priestesses were wealthy, held land (the most important commodity in an agrarian economy and the basis of status and power), employed workers and had the autonomy to enter into disputes with the Damos on their own (not represented by a husband or father). Eritha clearly brought a formidable case before the Damos as the scribe who recorded the dispute notes that the claim will be dealt with later. This is the first legal case known to have been argued in Europe.

Eritha is named as a land holder in other Pylian documents and she is recorded as making a grant of land to another woman, Huamia, also a priestess. [1] The shrine of which Eritha is the high priestess, at Sphagianes, is one which received monthly donations from the ruler of Pylos—one recording of a donation that included 1 gold goblet and a female servant (likely a slave) survives. [2]

Can we see a person like Eritha in the finely dressed, powerful looking women represented in wall painting and sculpture? If so, it is yet again an interesting female-privileging in Aegean art. Looking across the Linear B record of priests and priestesses, we find more priests than priestesses.

If the women we see in Aegean art are such priestesses, their role in representation would appear more significant than their male counterparts. This circumstance is made all the more interesting because, as it has been often noted, there are no images of rulers in Aegean Art—one of a handful of things that distinguishes it from contemporary Egyptian and Near Eastern visual culture where rulers are often displayed in a variety of media.

Non-elites

Non-elites

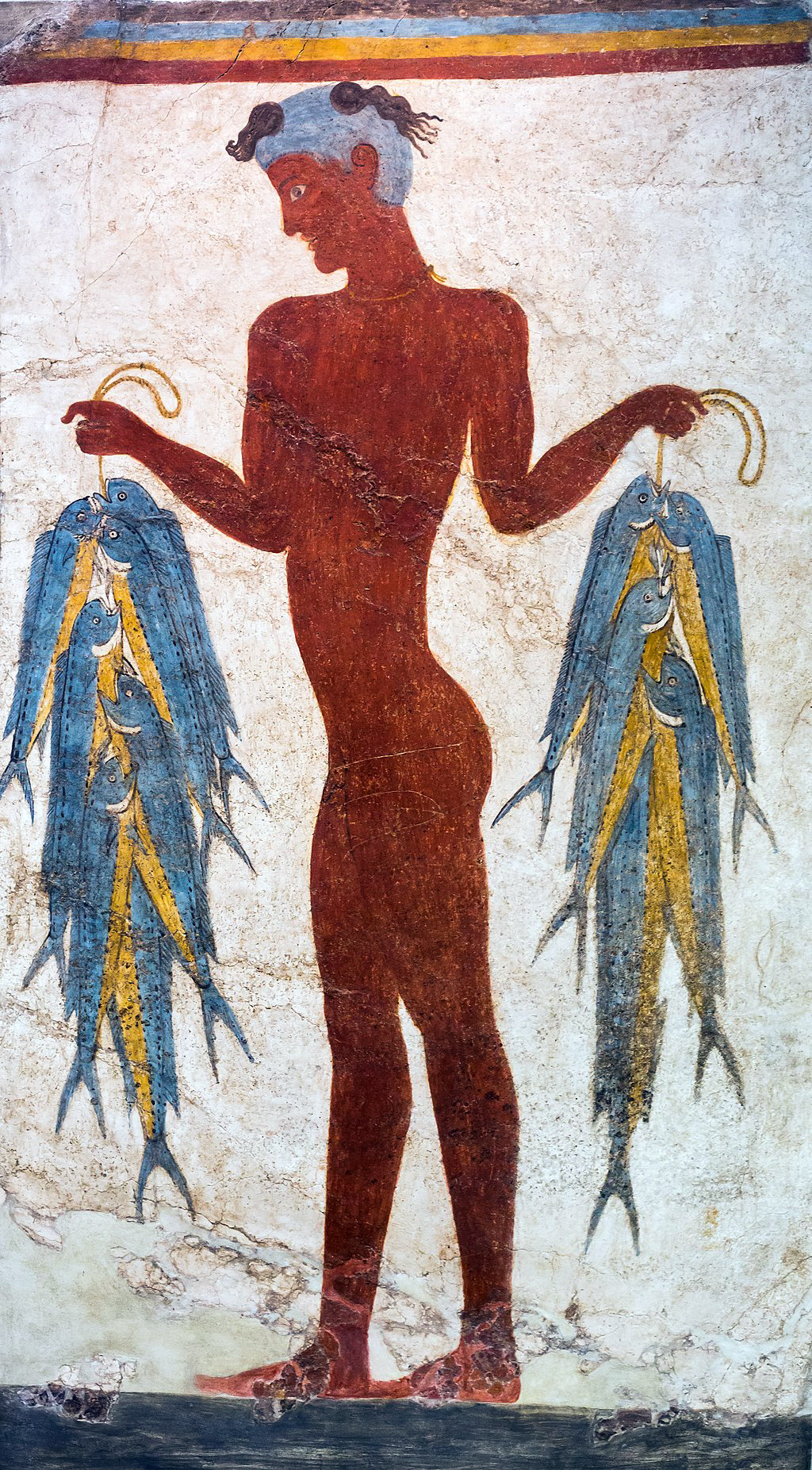

But what about non-elite women—and men? So much of the study of the Minoans and Mycenaeans is focused on palaces and elite trade in luxury goods. Very little has focused on the people producing these luxury goods and supporting palatial centers. Indeed, Aegean art rarely includes these non-elites, but they were fundamental to the material culture of the Aegean that we study. Among their rare appearances, we can include the image of a young fisherman among the paintings at Thera.

And, in a miniature painting from the same site, shepherds are seen tending their flock in the mountains—a distinctly non-elite activity. Shepherding, along with over two dozen other non-elite professions, are mentioned on the Linear B tablets. These are:

- sheep husbandry,

- wool harvesting,

- wool spinning and weaving,

- perfumed oil production,

- flax harvesting,

- spinning and linen production,

- cooking,

- building construction,

- bronze working,

- leather working,

- soldiering,

- olive oil and wine production,

- agricultural work,

- chariot repair,

- lapidary work,

- for seals and jewelry,

- gold,

- silver,

- ivory working,

- blue glass working,

- scribal work,

- flax spinning,

- weaving,

- garment making,

- pottery production,

- net making and ship building.

This list describes worlds of practice, teaching, fine skills, technical knowhow, virtuoso talent, project management, supply chain oversight, and plain old hard work—all performed by the non-elite. And, for many of these professions, we can today still treasure the fruits of their labor, such as the minutely detailed and stunning power of the gold and stone composite sculpture of the Minoan bull’s head rhyton or the Palaikastro Kouros.

Linear B tablets, so often mined for information about administrative control, ancient economic models, power hierarchies, and wealth distribution, are also a rich resource for information about the everyday people who lived and worked, worshipped and loved, struggled and died in the Aegean Bronze Age. To see these people in individual detail, unfortunately, is very difficult yet some glimpses are possible, as the frescoes at Thera demonstrate. At the Minoan palace at Phaistos, we have evidence of children’s and possibly women’s (their mothers?) finger and handprints on the insides and bases of pots. To be sure, to work in the pottery workshops of a palace site like Phaistos was to participate in the production of nothing less than one of the most important export products of the Aegean: painted pottery.

Palaces as popular ritual spaces

Palaces as popular ritual spaces

“Queen’s megaron,” East Wing, Knossos, Minoan (photo: Andy Montgomery, CC BY-SA 2.0)

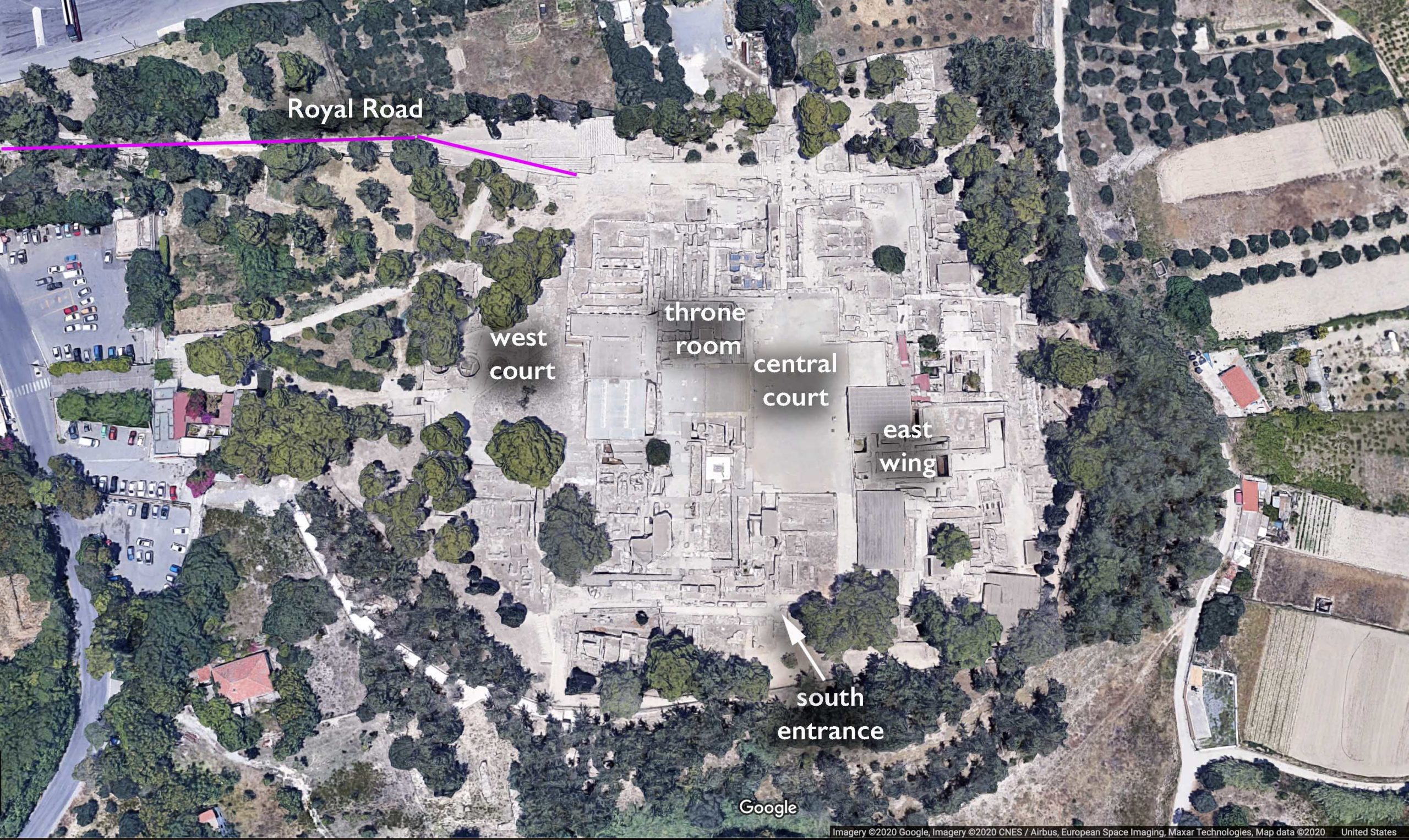

For good reason, the palace centers of the Aegean have been the focus of much archaeological investigation and study: thrones, richly painted rooms, dramatic façades, elaborate paving, labyrinthine passages, and even indoor plumbing created what must have been comfortable and exclusive spaces for the ruling theocratic elite to live and work. However, other parts of these structures were built to be used by the non-elite, including spaces for ritual performance to be observed and perhaps joined, to bind ordinary Minoans and Mycenaeans to their gods and leaders. By shifting focus away from throne rooms to civic spaces, these people are revealed.

The most vivid example of an architectural space made for a viewing public is what is referred to as the theatral area or west court of the Minoan Palaces on Crete. These are carefully paved plazas with adjacent broad steps for audience seating and are one of the most distinctive details of Minoan palaces. Smaller, paved courts with adjacent seating are also found in non-palatial sites. At Knossos, it is estimated that some 500 people could be accommodated in the largest of the courts. This is not just an audience of the elite, the non-elite and the workers of the palace also sat here.

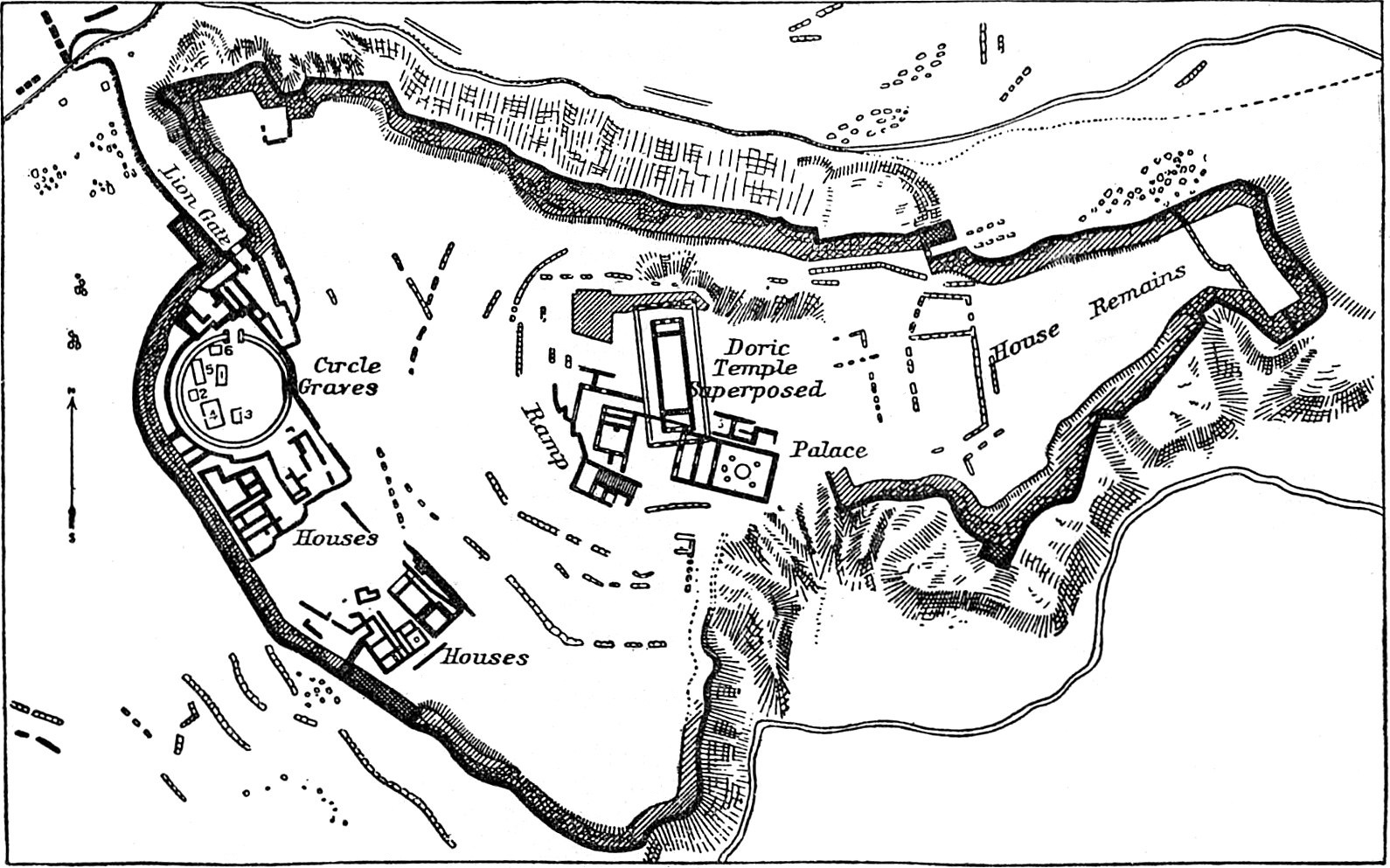

Turning to the Mycenaean mainland of Greece, interestingly, central sites, often citadels, lacked such open courts and, in general, had much smaller open spaces. However, these sites were nearly always situated on high plateaus, to afford a commanding view down, and so the population of the region would look up to them.

Looking past the archaeological remains of the “Palace” to the sea, Mycenae, Greece, c. 1600–1100 B.C.E.

Not unlike the way in which the spires of medieval pilgrimage churches were erected to great heights in order to function as focal points of prayer and inspiration for the surrounding population and travelers, the Mycenaean palaces’ commanding positions may imply a large, observant congregation of local people.

Interestingly, one of the most common painted motifs found in Mycenaean palaces is that of a single file procession of elites, finely dressed men and women (such as the one shown earlier from Thebes), holding offerings. Processions, like any performance, only have power through witness. Perhaps such painted processions mimic private elite performances held within the palaces but, given the limited interior space for groups, not many would have been able to observe. However, the siting of the Mycenaean citadels themselves would have made a procession leading up to them visible to many. Archaeologists have discovered a complex network of roads, including massive bridges over valleys, between Mycenaean sites, including Mycenae. Homer, who mentions Mycenae often, in relationship to its selfish king Agamemnon, describes it as broad wayed (meaning wide, well-paved), and busy with people and commerce.

These roads might be seen as a different sort of public space, not large and square as at the Minoan palaces, but long and broad. Leading to the palace centers within the high-walled citadels, they would have been the perfect venue for the thousands of workers and support personnel of the Mycenaean kings, to gather and wonder at the power of their labour, value of their craft, and purpose of their work.

Looking at the Bronze Age cultures of the Cycladic islands, Crete and the Greek mainland—with or without Homer—it is impossible not to wonder about the important people who held power and influence. Equally important, however, is understanding the lives and contributions of those who were not so important, for instance, women and the non-elite, the subjects of this chapter. It is only with a view to the full spectrum of human experience of the past that we can begin to write a history that means something to all of us.

Notes:

[1] PY Eb 416 and PY Ep 704 are two Linear B tablets. They use a particular citation style to designate the specific ones. PY designates a tablet’s origin in Pylos, and more than 1,000 tablets have been found there. The abbreviations like Eb, Ep, etc. designate different series to which the tablets belong.

[2] PY Tn 316