11 Chapter 11: The Mechanics of Human Language

Matthew Pawlowicz

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

- Describe the components of language studied by linguistic anthropologists

- Discuss some of the characteristics of human language, and how they compare to the characteristics of culture

- List some design features of language and describe how they distinguish human language from the communication of other primates

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. That definition is short, but it’s not exactly simple, is it? How do we study language scientifically? And what even is language?

Imagine you’re an alien, you’ve just arrived on Earth, and you need to figure out how to understand the language used in the particular earthling community that you’ve landed in. What kinds of things do you need to figure out? One of the first things you’ll need to know about that language is what counts as talking. Is this language signed or vocalized? In other words, what is the language modality? Many human languages are vocalized (or “spoken”). In this modality, language users make sounds with their larynx, tongue, teeth and lips, and receive sounds with their ears. Other human languages are signed. Language users make signs with their fingers, hands, wrists and forearms, and receive signs by sight or by touch. Even though they have very different modalities, sign and vocal languages share many properties in their grammars. In this section, we’ll try to reserve the words speaking and speech for vocal languages, and refer to language users when we’re talking about languages of any modality. In other places you might also see languaging used as a verb to mean “using language in any modality”.

Once you’ve figured out the modality, what next? You probably need to segment the stream of auditory or visual information into meaningful units. By observing carefully, you might be able to figure out that a particular sequence of sounds or gestures recurs in this language, and that some consistent meaning is associated with that sequence. For example, maybe you’ve noticed that the language users you’ve encountered make the sounds “cookie” as they’re offering you a round, sweet, delicious baked good. Or maybe you’ve noticed that when that word has a z sound at the end of it, cookies, you’re being offered more than one of them!

The part of the grammar that links up these forms with meanings is the mental lexicon. It’s a bit like a dictionary in your mind. Knowing a word in a language involves recognizing its form – the combination of signs or sounds or written symbols, and its meaning.

For the majority of words in the world’s languages, the link between form and meaning is arbitrary.

For example, the English word for this thing is pumpkin and the Nishnaabemwin word is kosmaan. There’s nothing inherently orange or round or vegetabley about either of those word forms: the pairing of that meaning to that form is arbitrary in each language. (But there are words whose form has an iconic, less arbitrary relationship their meaning; for instance onomatopoeias like ‘buzz’)

Suppose you’ve figured out that cookies are delicious and you want to ask your earthling hosts for more of them. To do that, you need to figure out how to control the muscles of your mouth, tongue, and lips to speak the word for cookie, or how to use your hands, fingers, wrists and forearms to sign the word. In other words, you need to know something about the articulatory phonetics of the language. This brings up an important point about grammar: when we know a language fluently, a lot of our grammatical knowledge is unconscious, or implicit. For the languages that you know, your knowledge of the lexicon is probably fairly conscious or explicit, and probably also some of your knowledge about your language’s morphology: that’s the combinations of meaningful pieces inside words (like how if you want more than one cookie you say cookies with a z). But you’re probably not as conscious of things like how you use your articulators to make the sounds k or z.

Our implicit knowledge of language also includes phonology, rules about the sounds or signs of the language (e.g. which ones are meaningful, how they can be combined, how they change in different contexts). Syntax is the part of your mental grammar that knows how words can or can’t be combined to make phrases and sentences, much of which is implicit. Syntax works hand in hand with semantics to allow the grammar to calculate the meanings of these phrases. And the pragmatics part of the mental grammar can help you to know what meanings arise in different contexts. For example, “I have some news,” could be interpreted as good news or bad news depending on the context.

All of these things are parts of the grammar: the things we know when we know a language. But a lot of this knowledge is implicit, and the thing about implicit knowledge is that it’s hard to observe. One of the most important jobs we’re doing in this section is trying to be explicit about what mental grammar is like, and about what kinds of evidence we can use to figure that out.

The Language Data Available for Study (phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics)

Phonology

Phonology is the use of sounds (or signs! the study of phonology has been extended to cover all of the ways language is produced) to encode messages within a spoken human language. Babies are born with the capacity to speak any language because they can make sounds and hear differences in sounds that adults would not be able to do. This is what parents hear as baby talk. The infant is trying out all of the different sounds they can produce. As the infant begins to learn the language from their parents, they begin to narrow the range of sounds they produce to ones common to the language they are learning, and by the age of 5, they no longer have the vocal range they had previously. For example, a common sound that is used in Indian language is /dh/. To any native Indian there is a huge difference between /dh/ and /d/, but for people like me who cannot speak Hindi, not only can we not hear the difference, but it is very difficult to even attempt to produce this sound.

A phoneme is the smallest phonetic unit in a language that is capable of conveying a distinction in meaning. For example, in English we can tell that pail and tail are different words, so /p/ and /t/ are phonemes. Two words differing in only one sound, like pail and tail, are called a minimal pair. The International Phonetic Association created the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), a collection of standardized representations of the sounds of spoken language.

Morphology

In linguistics, morphology is the study of how words are put together. For example, the word cats is put together from two parts: cat, which refers to a particular type of furry four-legged animal, and -s, which indicates that there’s more than one such animal.

Most words in English have only one or two pieces in them, but some technical words can have many more, like non-renewability, which has at least five (non-, re-, new, -abil, and -ity). In many languages, however, words are often made up of many parts, and a single word can express a meaning that would require a whole sentence in English. For example, in the Harvaqtuurmiutut variety of Inuktitut, the word iglujjualiulauqtuq has 5 pieces, and expresses a meaning that could be translated by the full English sentence “They (sg) made a big house.” (iglu = house, –jjua = big, –liu = make, –lauq = distant past, –tuq = declarative; this example is from a 2010 paper by Compton and Pittman).

Not all combinations of pieces are possible, however. To go back to the simple example of cat and -s, in English we can’t put those two pieces in the opposite order and still get the same meeting—scat is a word in English, but it doesn’t mean “more than one cat”, and it doesn’t have the pieces cat and -s in it, instead it’s an entirely different word. One of the things we know when we know a language is how to create new words out of existing pieces, and how to understand new words that other people use as long as the new words are made of pieces we’ve encountered before. We also know what combinations of pieces are not possible.

Syntax

Syntax is the study of rules and principles for constructing sentences in natural languages. It works by demonstrating the relationship between the words. For example, the order of words in the English sentence “The cat chased the dog” cannot be changed around or its meaning would change: “The dog chased the cat” (something entirely different) or “Dog cat the chased the” (something meaningless). English relies on word order much more than many other languages do because it has so few morphemes that can do the same type of work. For example, in our sentence above, the phrase “the cat” must go first in the sentence, because that is how English indicates the subject of the sentence, the one that does the action of the verb. The phrase “the dog” must go after the verb, indicating that it is the dog that received the action of the verb, or is its object. Other syntactic rules tell us that we must put “the” before its noun, and “-ed” at the end of the verb to indicate past tense. In Russian, the same sentence has fewer restrictions on word order because it has bound morphemes that are attached to the nouns to indicate which one is the subject and which is the object of the verb. So the sentence koshka [chased] sobaku, which means “the cat chased the dog,” has the same meaning no matter how we order the words, because the -a on the end of koshka means the cat is the subject, and the -u on the end of sobaku means the dog is the object.

Semantics

Semantics is the study of meaning. The whole purpose of language is to communicate meaning about the world around us so the study of meaning is of great interest to linguists and anthropologists alike. The field of semantics focuses on the study of the meanings of words and other morphemes as well as how the meanings of phrases and sentences derive from them.

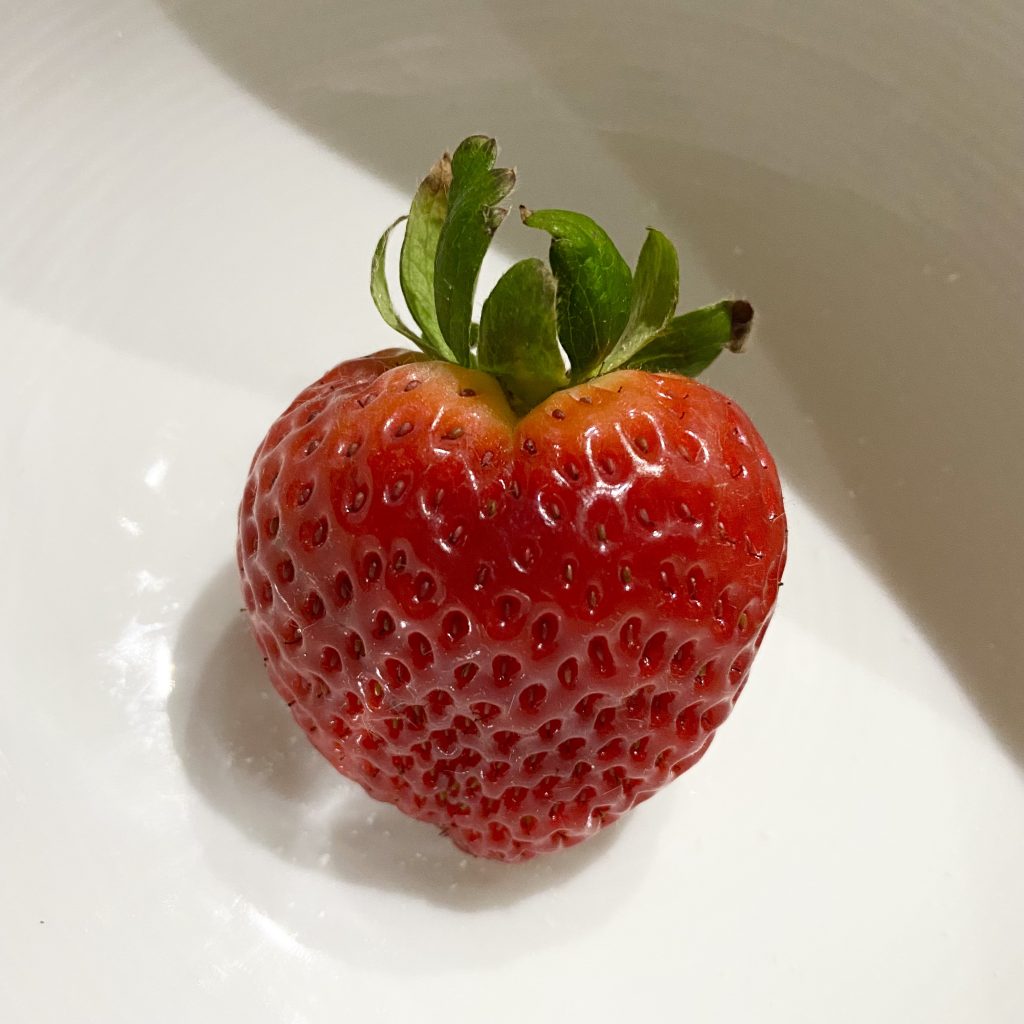

For example, the words ode’imin and strawberry mean the same thing. ode’imin is an Ojibwe (Anishinaabemowin) word, and strawberry is an English word. But what does it mean for them to “mean the same thing”? What we want to figure out is something like this: what is the knowledge about the word ode’imin that an Ojibwe speaker stores in their head, such that when they utter the word, they know it points to that juicy red fruit with small seeds on the surface (Figure 4)? Similarly, what is the knowledge about the word strawberry that English speakers have in their head, such that they know that this word in English points to this same fruit? Both the word ode’imin and the word strawberry carry some sort of content, and this information allows for Ojibwe and English language users to say “Yes, that is an ode’imin/strawberry” or “No, that is not an ode’imin/strawberry” for any given object. In this way, the two words “mean the same thing”.

Pragmatics

The study of pragmatics looks at the social and cultural aspects of meaning and how the context of an interaction affects it. One aspect of pragmatics is the speech act. Any time we speak we are performing an act, but what we are actually trying to accomplish with that utterance may not be interpretable through the dictionary meanings of the words themselves. For example, if you are at the dinner table and say, “Can you pass the salt?” you are probably not asking if the other person is capable of giving you the salt. Often the more polite an utterance, the less direct it will be syntactically. For example, rather than using the imperative syntactic form and saying “Give me a cup of coffee,” it is considered more polite to use the question form and say “Would you please give me a cup of coffee?”

Language and Cultural Relativism: There’s no such thing as bad language!

The previous section was a very quick tour of some of the parts of the mental grammar. We’ll be discovering a lot more about grammar throughout this section. Notice that we’re using the term grammar a little differently from how you might have encountered it before. Maybe your experience of grammar is as a textbook or style guide with a set of rules in it, rules that lead to consequences if you break them — you’ll lose points on your essay or get corrected with a red pen. What we’re most interested in is the mental grammar: the system in your mind that allows you to understand and be understood by others who know your language. Every human language has a grammar: that’s how the users of each language understand each other, but the mental grammar of any two speakers, even if they are both fluent, will not be exactly the same.

This is a really important idea. One way that people sometimes express racist, colonialist, and ableist ideas is to deny the validity of a language by claiming that it “has no grammar”. But the truth is that all languages have grammar. All languages have a system for forming words, a way of organizing words into sentences, a systematic way of assigning meanings. Even languages that don’t have alphabets or dictionaries or published books of rules have users who understand each other; that means they have a shared system, a shared grammar. Using linguists’ techniques for making scientific observations about language, we can study these grammars.

The other important thing to keep in mind is that no grammar is better than any others. Maybe you’ve heard someone say, “Oh, I don’t speak real Italian, just a dialect,” implying that the dialect is not as good as so-called “real Italian.” Or maybe you’ve heard someone say that Québec French is just sloppy; it’s not as good as the French they speak in France. Or maybe you’ve heard someone say that nobody in Newfoundland can speak proper English, or nobody in Texas speaks proper English, or maybe even nobody in North America speaks proper English and the only good English is the Queen’s English that they speak in England.

From a linguist’s point of view, all languages and dialects are equally valid!

There’s no linguistic way to say that one grammar is better or worse than another. This is part of what it means to study grammar from a scientific approach: scientists don’t rate or rank the things they study. Ichthyologists don’t rank fish to say which species is more correct at being a fish, and astronomers don’t argue over which galaxy is more posh. In the same way, doing linguistics does not involve assigning a value to any language or variety or dialect. We need to acknowledge, though, that many people, including linguists, do attribute value to particular dialects or varieties, and use social judgments about language to create and reinforce hierarchies of power, privilege and status.

One of the most fundamental properties of grammar is creativity. One obvious sense of the word creative has to do with artistic creativity, and it’s true that we can use language to create beautiful works of literature. But that’s not the only way that human language is creative. The sense of creativity that we’re most interested in in this book is better known as productivity. Every language can create an infinite number of possible new words and sentences. Every language has a finite set of words in its vocabulary – maybe a very large set, but still finite. And every language has a small, finite set of principles for combining those words. But every language can use that finite vocabulary and that finite set of principles to produce an infinite number of sentences, new sentences every single day.

A consequence of the fact that grammar is productive is that languages are always changing. Have you heard your teachers or your parents say something like, “Kids these days are ruining English! They should learn to speak properly!” Or if you grew up speaking Mandarin, maybe you heard the same thing, “Those teenagers are ruining Mandarin! They should learn to speak properly!” For as long as there has been language, older people have complained that younger people are ruining it. Some countries, like France and Germany, even have official institutes that make rules about what words and sentence structures are allowed in the language and which ones are forbidden. But the truth is every language changes over time. Languages are used by humans, and as humans grow and change, and as our society changes, our language changes along with it. Some language change is easy to observe in the lexicon: we need to introduce new words for new concepts and new inventions. For example, the verb google didn’t exist when I was an undergraduate student, and now googling is something I do nearly every day. Languages also change in their phonetics and phonology, and in their syntax, morphology and semantics.

The Design Features of Language (and comparison with communication of other primates)

All animals communicate and many animals make meaningful sounds. Others use visual signs, such as facial expressions, color changes, body postures and movements, light (fireflies), or electricity (some eels). Many use the sense of smell and the sense of touch. Most animals use a combination of two or more of these systems in their communication. But their systems are closed systems in that they cannot create new meanings or messages. Human communication is an open system that can easily create new meanings and messages. Most animal communication systems are basically innate; they do not have to learn them, but some species’ systems entail a certain amount of learning. For example, songbirds have the innate ability to produce the typical songs of their species, but most of them must be taught how to do it by older birds. Great apes and other primates have relatively complex systems of communication that use varying combinations of sound, body language, scent, facial expression, and touch. Their systems have therefore been referred to as a gesture-call system. Humans share a number of forms of this gesture-call, or non-verbal system with the great apes. Spoken language undoubtedly evolved embedded within it. All human cultures have not only verbal languages, but also non-verbal systems that are consistent with their verbal languages and cultures and vary from one culture to another.

Human language is qualitatively and quantitatively different from the communication systems of all other species of animals. Linguists have long tried to create a working definition that distinguishes it from non-human communication systems. Linguist Charles Hockett’s (1963) solution was to create a hierarchical list of what he called design features, or descriptive characteristics, of the communication systems of all species, including that of humans. Human language differs from non-human communication in that it possesses all of the design features. A number of great apes, including gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos and orangutans, have been taught human sign languages with all of the human design features. In each case, the apes have been able to communicate as humans do to an extent, but their linguistic abilities (e.g. what they communicate about) are reduced by the limited cognitive abilities that accompany their smaller brains.

Hockett’s Design Features

- A mode of communication by which messages are transmitted through a system of signs, using one or more sensory systems to transmit and interpret, such as vocal-auditory, visual, tactile, or kinesic;

- Semanticity: the signs carry meaning for the users

- Pragmatic function: all signs serve a useful purpose in the life of the users, from survival functions to influencing others’ behavior.

- Interchangeability: the ability of individuals within a species to both send and receive messages. One species that lacks this feature is the honeybee. Only a female “worker bee” can perform the dance that conveys to her hive-mates the location of a newly discovered food source. Another example is the mockingbird whose songs are performed only by the males to attract a mate and mark his territory.

- Cultural transmission: the need for some aspects of the system to be learned through interaction with others, rather than being 100 percent innate or genetically programmed.

- Arbitrariness: the form of a sign is not inherently or logically related to its meaning; signs are symbols.

- Discreteness: every human language is made up of a small number of meaningless discrete sounds. That is, the sounds can be isolated from each other, for purposes of study by linguists, or to be represented in a writing system.

- Duality of patterning (two levels of combination): at the first level of patterning, these meaningless discrete sounds, called phonemes, are combined to form words and parts of words that carry meaning, or morphemes. In the second level of patterning, morphemes are recombined to form an infinite possible number of longer messages such as phrases and sentences according to a set of rules called syntax.

- Displacement: the ability to communicate about things that are outside of the here and now made possible by the features of discreteness and duality of patterning. While other species are limited to communicating about their immediate time and place, we can talk about any time in the future or past, about any place in the universe, or even fictional places.

- Productivity/creativity: the ability to produce and understand messages that have never been expressed before or to express new ideas. People do not speak according to prepared scripts, as if they were in a movie or a play; they create their utterances spontaneously, according to the rules of their language. It also makes possible the creation of new words and even the ability to lie.

Terms You Should Know

Study Questions

- What are the different kinds of language data available for study? How do they connect to one another?

- We know some characteristics that describe human language (i.e. it is always changing!). How do those characteristics compare with what we know about culture, and what do they mean for how linguistic anthropologists should study language?

- How does human language compare to the communication systems of other primates? What does that suggest about studying the origins of human language?

- What would language be like without any of the design features? How would it cease to work as we are used to language working?

References

Compton, Richard and Pittman, Christine. 2010. Word-formation by phrase in Inuit. Lingua, 120(9): 2167-2192.

Hockett, Charles. 1963. The Problem of Universals in Language. In J. Greenberg (ed.), Universals of Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

A Derivative Work From

Allard-Kropp, Manon. 2020. Languages and Worldview.

Anderson, Catherine, et al. 2022. Essentials of Linguistics, 2nd Edition.

Light, Linda. 2020. Language. In Nina Brown, et al. (eds.) Perspectives, an Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd Edition.

The study of human language

The form of communication (e.g. spoken, signed) used by a language and its speakers.

The things you know, consciously or unconsciously, when you know a language.

The use of specific sounds or signs to encode messages within a given language.

Two words differing in only one sound, thereby showing that the two sounds that differ carry meaning in the language.

The study of the pieces of meaning within a given language. For many languages (but not all!), how words are put together.

The study of how to show the relationship between words and construct meaningful sentences within a language.

The study of the meaning of words and phrases within a language.

The study of how context effects meaning within a language.

The fact that each language could creatively produce an infinite number of new words and sentences (even if they don't actually do so).

The communication systems of great apes and other non-human primates, relying on sound and body language.