19 Chapter 19: Gender and Marriage in Anthropology

Christopher A Brooks

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Define the concepts of sex and gender and explain the difference between the two concepts.

- Distinguish between public and private social realms and identify the consequences of this distinction for

gender categories. - Define the concept of intersex.

- Give a detailed example of a culture with multiple genders.

- Explain the concept of gender ideology and identify two such ideologies

- State the anthropological definition of marriage.

- Provide examples of different forms of marriage across cultures.

- Describe how marriage intersects with residence rules, family, and kinship.

A friend announces, “My sister just had a baby last night!” Many people will immediately ask, “Is it a boy or a girl?” Gender is central to the way people think about and interact with others.

Anthropologists are curious about the many ways in which gender shapes impressions and assumptions about people and why gender is such a primary concern. Gender influences how people think about their own identities, how they present themselves to others, and how they plan to lead their lives. People’s sexual identities and desires are shaped by gendered notions of themselves and others. Power operates in cultural constructions of gender and sexuality. Ideas about gender also influence marriage practices, as we will see.

Sex, Gender, and Sexuality in Anthropology

For many people, male and female refer to natural categories that neatly divide up the human population. Often, people associate these two categories with different abilities and personality traits. Setting aside these ideas and assumptions, anthropologists explore aspects of human biology and culture to understand where notions of gender come from while documenting the diversity of gender and sexuality in cultures all over the world, past and present.

The Terms: Sex, Gender, and Sexuality

In the social sciences, the term sex refers to the biological categories of male and female (and potentially other categories, as discussed later in this chapter). The sex of a person is determined by biological and anatomical features, including (but not limited to): visible genitalia (e.g., penis, testes, vagina), internal sex organs (e.g., ovaries, uterus), secondary sex characteristics (e.g., breasts, facial hair), chromosomes (XX for females, XY for males, and other possibilities), reproductive capabilities (including menstruation), and the activities of growth hormones, particularly testosterone and estrogen. It may seem as though nature divides humans neatly into females and males, but such a long list of distinguishing factors results in a great deal of ambiguity and diversity within categories. For instance, hormonal influences can produce results different from the ways that people typically develop. Hormonal influences shape the development of sex organs over time and can stimulate the emergence of secondary sex characteristics associated with the other sex. Clothes on or clothes off, people can have body features associated with one sex category and chromosomes associated with another.

While sex is based on biology, the term gender was developed by social scientists to refer to cultural roles based on these biological categories. The cultural roles of gender assign certain behaviors, relationships, responsibilities, and rights differently to people of different genders. As elements of culture, gender categories are learned rather than inherited or inborn, making childhood an important time for gender enculturation. As opposed to the seeming universality of sex categories, the specific content of gender categories is highly variable across cultures and subject to change over time.

The two terms, biological sex and cultural gender, are often distinguished from one another to clarify the differences embedded in “nature” versus the differences constructed by “culture.” But are biological sex categories based on an objective appraisal of nature? Are sex categories universal and durable? Some scholars question the biological objectivity of sex and its opposition to the more flexible notion of gender.

Associated with sex and gender, the concept of sexuality refers to erotic thoughts, desires, and practices and the sociocultural identities associated with them. The complex ways in which people experience their own bodies and perceive their own gender contribute to the physical behaviors they engage in to achieve pleasure, intimacy, and/or reproduction. This complex of thoughts, desires, and behaviors constitutes a person’s sexuality.

Some cultures have very strict cultural norms regarding sexual practices, while others are more flexible. Some cultures confer a distinctive identity on people who practice a particular form of sexuality, while others allow a person to engage in an array of sexual practices without adopting a distinctive identity associated with those practices (Nanda 2000). Sexual orientation refers to sociocultural identities associated with specific forms of sexuality. For instance, in American culture, sex between a woman and a man is conventionalized into the normative identity of heterosexual. If you are a person who practices that kind of sex (and only that kind), then most Americans would consider you to be a heterosexual person. If you are a person who engages in sex with someone of the same sex/gender category, then in American culture, you would be considered a gay person (if you identify as male) or a lesbian (if you identify as female). So anxious are Americans about these categorical identities that many young people who have erotic dreams or passing erotic thoughts about a same-sex friend may worry that they are “really” not heterosexual. As American norms have changed over the past several decades, some people who have romantic, emotional, or erotic feelings toward people of their own gender and another gender have adopted the identity of bisexual. People who may have erotic desires about and relations with others without regard to their biological sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation may consider themselves to be pansexual. Even more recently, some people who do not engage in sexual thoughts, desires, or practices of any kind have embraced the identity of asexual. While there are many aspects and manifestations of sexual orientation, sexual orientation is considered to be a central and durable aspect of a person’s sociocultural identity.

In some cultures, heterosexuality was previously thought to be the most “natural” form of sexuality, a notion called heteronormativity. This notion has been challenged by research and the growth of the global LGBTQIA+ movement. In other cultures, people are allowed or even expected to engage in more than one form of sexuality without necessarily adopting any specific sexual identity. This is not to say that these other cultures are consistently more liberal and tolerant of sexual diversity. In many societies, it is acceptable for people to engage in same-sex practices in certain contexts, but they are still expected to marry someone of the opposite sex and have children.

Scholars who have studied sexuality in many cultures have also pointed out that a person’s gender identity, sexual orientation, and sexuality tend to change significantly over the life span, responding to different contexts and relationships. The term queer, originally a pejorative term in American culture for a person who did not conform to the rigid norms of heterosexuality, has been appropriated by people who do not abide by those norms, particularly people who take a more situational and fluid approach to the expression of gender and sexuality. Rather than a set of fixed and durable identities, queer gender and sexuality are more fluid, constantly emerging, and contingent on multiple factors.

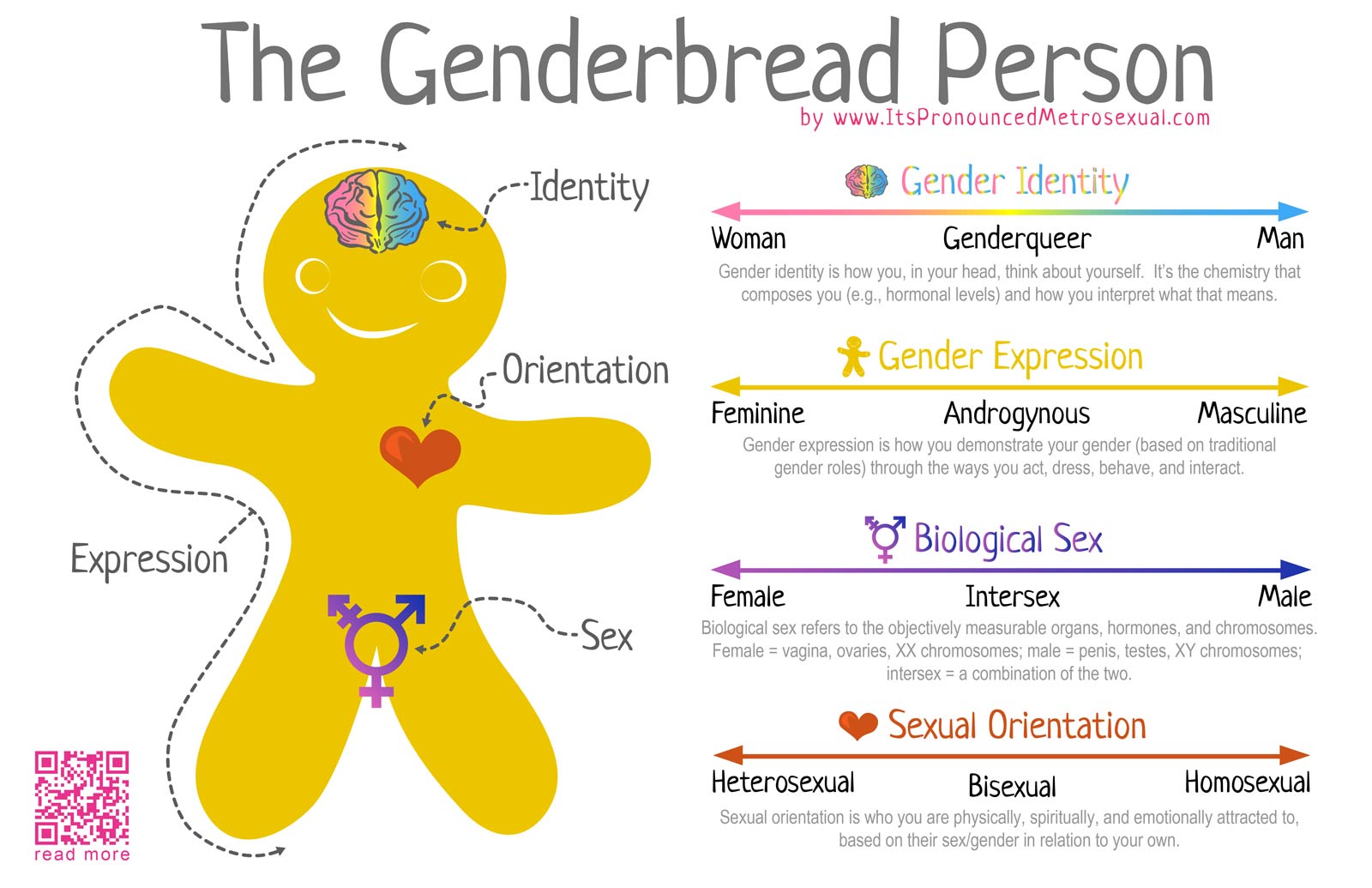

As complex as sex, gender, and sexuality can be, it is helpful to have a diagram illustrating the possible relationships among these factors. Activist Sam Killermann has developed a useful diagram known as “The Genderbread Person,” depicting the various aspects of identity, attraction, expression, and physical characteristics that combine in the gender/sexuality of whole persons.

Evidence from Biological Anthropology

Given humans’ close biological relationship to primates, one might expect to see similar dynamics of sex and gender between human and nonhuman primate social groups. Biologists and primatologists have examined sex differences in the biology and behavior of both nonhuman and human primates, looking for commonalities that might suggest a common biological genesis for sex/gender categories.

Primate Sex Differences: Biology and Behavior

In the 1950s, a time when American men were supposed to be breadwinners and American women were urged to be housewives and mothers, most primatologists believed that males were the actors in primate social life, while females were passive, marginal figures. Primatologists of the time believed that males constantly competed against one another for dominance in a rigid group hierarchy, while females were more narrowly interested in raising young (Fedigan and Fedigan 1989). In fact, primatologists described the total social organization of primates in terms of male competition. This view went along with Charles Darwin’s notion that males are forced to compete for the opportunity to mate with females and so, therefore, must be assertive and dominant. Females, in Darwin’s theory, were shaped by evolution to choose the strongest male to mate with and then concern themselves exclusively with nurturing their offspring to adulthood.

By the 1980s, however, a number of strong studies were showing some very surprising things about primate social organization. First, most primate groups are essentially composed of related females, with males as temporary members who often move between groups. The heart of primate society, then, is not a set of competitive males but a set of closely bonded mothers and their young. Females are not marginal figures but central actors in most social life. The glue that holds most primate groups together is not male competition but female kinship and solidarity.

Second, social organization in primates turned out to be incredibly complex, with both males and females actively strategizing for desirable resources, roles, and relationships. Research on a number of primate species has demonstrated that females are often sexually assertive and highly competitive. Female primates actively exercise their preference to mate with certain male “friends” rather than aggressive or dominant males. For males, friendliness with females may be a much better reproductive strategy than fighting with other males. Moreover, many primatologists have begun to identify cooperation rather than competition as the central feature of primate social life, while still recognizing competition for resources by both males and females in their pursuit of survival and reproduction (Fedigan and Fedigan 1989). What this means, in a nutshell, is that (1) both females and males are competitive, (2) both females and males are cooperative, and (3) both females and males are central actors in primate social life.

While evidence suggests that in primate groups males and females are equally important to social life, this still leaves open the question of biological differences and their link to behavioral differences. The anatomy of primate males and females differs in two main respects. First, of course, adult females can and often do experience pregnancy and bear offspring. The females of most primate species are often pregnant or nursing for most of their adult lives and devote more time and resources to care of young than males do (although there are some notable exceptions, such as certain species of New World monkeys). And some researchers have noted the tendency of juvenile females to pay more attention to primate babies in the group than do juvenile males.

Second, male primates tend to be slightly bigger than females, although this difference itself is quite variable. The size difference between males and females of any species is referred to as sexual dimorphism. Male and female gibbons are nearly the same size, while male gorillas are nearly twice the size of females. Female chimpanzees are about 75 percent the size of males. Human females are about 90 percent the size of males, making human sexual dimorphism closer to gibbons than chimpanzees.

Some researchers suggest that a high level of sexual dimorphism is associated with strong male dominance, rigid hierarchy, and male competition for mating with females. Certainly these features reinforce one another in gorilla society. A low level of sexual dimorphism may be associated with long-term monogamy, as with gibbons. However, anthropologist Adrienne Zihlman cautions against making any firm judgments about the relationship between biological features such as size and behavioral features such as sexual relations. She remarks, “There is no simple correlation between anatomy and behavioral expression, within or between species” (1997: 100). Reviewing research on sex differences in gibbons, chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans, she concludes that each species features a unique “mosaic” of sex differences involving anatomy and behavior, with no clear commonality that might predict what is “natural” for humans.

Humans’ closest primate relatives are chimpanzees and bonobos, both sharing 99 percent of their DNA with humans, and yet each species exhibits very different gender-related behaviors. Bonobos are female-dominant, while chimpanzees are male-dominant. Bonobo groups are mostly egalitarian and peaceful, while chimpanzee groups are intensely hierarchical, with frequent male aggression within and between groups. Sexual behavior among bonobos is remarkably frequent and extraordinarily variable, with a wide range of same-sex and opposite-sex pairings involving various forms of genital contact. Some researchers believe that sexual contact helps build social bonds and ease conflicts in bonobo groups. Bonobos have been called the “make love, not war” primate. Sexual behavior among chimpanzees is also variable but much more limited to opposite-sex pairings. A female in estrus may mate with several males, a pattern called opportunistic mating. Short-term exclusive relationships may form, in which a male guards a female to prevent other males from mating with her. Consortships also happen, in which a female and a male leave the group for a week or more.

With such variability between humanity’s two closest DNA relatives, it is not possible to use nonhuman primate behavior to make assertions about what is “natural” for human males and females. In fact, with regard to gender, the lessons of primatology may be that apes (like humans) are biologically quite flexible and capable of many social expressions of gender and sexuality.

Human Sex Differences: Biology and Behavior

Just as with primate research, research on human biological sex differences has been considerably slanted by the gender bias of the (often male) researchers. Within the Euro-American intellectual tradition, scholars in the past have argued that women’s biological constitution makes them unfit to vote, go to college, compete in the job market, or hold political office. More recently, beliefs about the different cognitive abilities of men and women have become widespread. Males are supposedly better at math and spatial relationships, while females are better at language skills. Hormonal activities supposedly make males more aggressive and females more emotional.

In her book Myths of Gender, biologist Anne Fausto-Sterling (1992) conducts a massive review of research on cognitive and behavioral sex/gender differences in humans. Looking very closely at the data, she finds that the vast number of studies show no statistically significant difference whatsoever between the cognitive abilities of boys and girls. A minority of studies found very small differences. For instance, among four studies of abstract reasoning abilities, one study indicated that females were superior in this skill, one study indicated that males were superior, and two studies showed no difference at all. Overall, when differences are found in verbal abilities, girls usually come out ahead, but the difference is so small as to be irrelevant to questions of education and employment. Likewise, more than half of all studies on spatial abilities find no difference between girls and boys. When differences are found, boys come out ahead, but the difference is again very small. Looking at the overall variation of skill levels in this area, only about 5 percent of it can be attributed to gender. This means that 95 percent of the differences are due to other factors, such as educational opportunities.

Even the tiny differences that may exist in the cognitive talents of different genders are not necessarily rooted in biological sex differences. Several studies of spatial abilities have shown that boys may initially perform better on spatial ability tests, but when given time to practice, girls increase their skill levels to become equal to boys, while boys remain the same. Some researchers reason that styles of play such as sports, often encouraged more by parents of boys, may build children’s spatial skills. Parenting styles, forms of play, and gender roles—all elements of culture—may shape the data more than biology. Cross-cultural studies also indicate that culture plays an important role in shaping abilities. A study of the Inuit found no differences at all in the spatial abilities of boys and girls, while in a study of the Temne of Sierra Leone, boys outperformed girls. Inuit girls are generally allowed more freedom and autonomy, while Temne girls are more restricted in their activities.

Similar complexities emerge in the analysis of studies on aggression. Fausto-Sterling found that most studies revealed no clear relationship between testosterone levels and levels of aggression in males. Moreover, testosterone aggression studies have been riddled with problems such as poor methodology, questionable definitions of aggression, and an inability to prove whether testosterone provokes aggression or the other way around. Where differences in aggression between girls and boys are documented, some researchers have concluded that cultural factors may play a strong role in producing those differences. Anthropologist Carol Ember studied levels of aggression among boys and girls in a village in Kenya. Overall, the boys exhibited more aggressive behavior, but there were exceptions. In families lacking girl children, boys were made to perform more “feminine” work such as childcare, housework, and fetching water. Boys who regularly performed those tasks exhibited less aggression than other boys—up to 60 percent less for boys who performed a lot of this work.

As with the primate research on sex differences, research on the brains, bodies, and behaviors of male and female humans does not seem to suggest that significant behavioral differences are biologically hardwired. While researchers have discovered differences in the cognitive talents and social behaviors of males and females, those differences are very small and could very well be due to social and cultural factors rather than biology. As with bonobos and chimpanzees, humans are biologically quite flexible, allowing for a diverse array of forms of gender and sexuality.

Performing Gender Categories

So if gender is not a “natural” expression of sex differences, then what is it? Cultural anthropologists explore how people’s ideas of gender are formed in their minds, bodies, social institutions, and everyday practices.

Gender not only influences how people think about themselves and others; it also influences how they feel about themselves and others—and how others make them feel. Romantic or sexual passion draws from gendered identities and reinforces them. In the words sung by Aretha Franklin, “You make me feel like a natural woman.” There is something about gendered identity that can feel deep and real. The sense that some trait is so profoundly deep and consequential that it creates a common identity for everyone who has that trait is called essentialism. Gender essentialism is the basis of a lot of circular thinking. When a boy kicks a ball through the neighbor’s window and someone says, “Boys will be boys!”—that’s essentialist. You may be familiar with this little essentialist ditty from Euro-American culture:

Sugar and spice and everything nice, that’s what little girls are made of.

Snips and snails and puppy dog tails, that’s what little boys are made of.

In this view, gender is what you’re “made of”—that is, your biological essence.

And yet, biology and archaeology have shown that gender differences are complicated and illusory. What is a natural woman . . . or a natural man? Cultural anthropologists find that some cultures consider men and women to be quite similar, while other cultures emphasize differences between genders. All cultures promote a distinctive set of ideal norms, values, and behaviors, considering those ideals to be natural and good. In cultures that consider men and women to be similar, those ideals apply equally to all people. In cultures that consider men and women to be quite different, one set of ideals applies to men and another set applies to women. In all cases, the content of those ideals varies enormously across cultures.

Cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead conducted research on gender in several societies in New Guinea. She confessed that she had initially assumed that gendered behaviors were grounded in biological differences and would vary only slightly across cultures. In her 1935 book, Sex and Temperament, she describes her surprise at discovering three cultural groups with vastly different interpretations of gender. Among the Arapesh and Mundugumor, men and women were considered temperamentally quite similar, with little acknowledgment of emotional or behavioral differences between them. The Arapesh valued cooperation and gentleness, expecting everyone to show tolerance and support for younger and weaker members of the group. In contrast, among the Mundugumor, both men and women were expected to be competitive, aggressive, and violent. Among the Tchambuli (or Chambri), however, men and women were assumed to be temperamentally different: men were seen to be neurotic and superficial, while women were thought of as relaxed, happy, and powerful. While Mead’s dramatic findings have been subject to criticism, subsequent analysis and fieldwork by other anthropologists have largely substantiated her main conclusions (Lipset 2003).

Like race, gender involves the cultural interpretation of biological differences. To make things even more complicated, the very process of cultural interpretation alters the way those biological differences are perceived and experienced. In other words, gender is based on a complex dynamic of culture and nature. Gender identities feel more natural than, say, class or religious identities because they involve direct reference to one’s body. Most people’s bodies feel “natural” to them even with the knowledge that culture shapes the way individuals experience their bodies. In this way, gender is not so much natural as it is naturalized, or made to seem natural.

In the past three decades, many gender scholars have argued that gender is not so much a set of naturalized categories to which people are assigned as it is a set of cultural identities that people perform in their daily lives. In her influential book Gender Trouble (1990), philosopher Judith Butler describes gender as a kind of relation between categorical norms and individual performances of those norms. In childhood, people are presented with the idealized categories of male and female and taught how to enact the category to which they have been assigned. For Butler, gender is “an impersonation” because “becoming gendered involves impersonating an ideal that nobody actually inhabits.”

If gender involves both established categories and everyday performances, then it’s necessary to pay close attention to the idealized norms of gender constructed in a particular cultural context and the various ways in which people enact those norms in practice. In Gender and Sexuality in Muslim Cultures (Ozyegin 2015), researchers studying Muslim communities in Turkey, Egypt, Pakistan, Syria, and Iran examine the ideals of Muslim masculinity and femininity in those contexts, as well as how those ideals are enacted and resisted in everyday life. Salih Can Açıksôz describes how the Turkish government provides disabled veterans with access to assisted reproductive technologies so that they can father children. The aim of this program is to make them feel like “real men” again, renormalizing their masculinity in the context of heterosexual family life. Maria Frederika Malmstroöm shows how Muslim women in Cairo strive to achieve the purity and cleanliness associated with femininity through such practices as cooking, skin care, and becoming circumcised. The idea is that gender is not at all “natural”; you have to work at it every day and make sure you’re doing it right. If you cannot seem to approximate your gender norm for some reason, then your family members, friends, and even the government may step in to help you perform it.

Women and Feminist Theories of Gender

Inspired by the women’s movement of the 1960s, many female anthropologists in the early 1970s began taking a critical look at mainstream Anthropology, noticing how the discipline focused almost exclusively on the activities of men—both as researchers and objects of study. In most early and mid-20th-century ethnographies, men were represented as the major social actors, and men’s activities were assumed to be the most important ones. Where were the women, and what were they doing? Calling for an “anthropology of women,” many feminist anthropologists set out to correct the ethnographic record by focusing more on the voices, perspectives, and practices of women in cultures all over the world.

Examining the roles of women in many cultures, feminist anthropologists began to see some patterns. In contexts where women made strong and direct contributions to subsistence and the economy, they seemed to enjoy greater social status and equality with men. Among gatherer-hunters, for instance, where women’s gathering activities provided the majority of calories in the overall diet, women held positions of equality. In contexts where women were relegated to the home as housekeepers and mothers, they were more subordinate to men and were not considered equal actors in sociocultural activities. Agricultural and industrial societies both created “public” spheres of work separate from the “private” sphere of the household. Women in these societies were more often assigned to work in the private sphere and sometimes even prohibited from entering public areas. In capitalist market systems, the domestic work of housewives is uncompensated and virtually invisible. Cultural anthropologist Michelle Rosaldo (1974) argued that the division of sociocultural life into public and private spheres resulted in the marginalization of women.

While this early wave of feminist anthropology focused on women, more recently researchers have questioned the essentialism of this approach. Is gender always the most important factor in determining the status of women in all cultures? Gender intersects with race, class, ethnicity, age, sexuality, and physical ability to make the experiences of women diverse and complex, a position called intersectionality. Due to economic necessity, women of color in American society have more often been forced to work outside the home. In fact, many privileged white women have been able to hire domestic workers to relieve them of their household chores—and often those domestic workers have been women of color. For cooks, nannies, and housekeepers, the private domestic sphere of privileged women constitutes their own public sphere of work, supervised by the woman of the house. The experiences of people of color complicate the idea that women are subordinated through their confinement to the private domestic sphere.

Men and Masculinities

While men had been the primary focus of anthropological research up to the 1970s, they had always been studied as general representatives of their cultures. The establishment of gender studies in anthropology prompted both male and female anthropologists to view all persons in a culture through the lens of gender. That is, men began to be seen as not just “people” but people who are socialized and culturally constructed as men in their societies (Gutmann 1997). In the 1990s, a wave of scholarship emerged probing the identities of men and the features of masculinity across cultures.

Cultural anthropologist Stanley Brandes (1980) studied how men in Monteros, an Andalusian town in southern Spain, used folklore to express their ambivalent feelings of desire and hostility toward women. Through their jokes, pranks, riddles, wordplay, nicknames, and dramas, men in Monteros built camaraderie and constructed a male-centered ideology of dominance. A good part of each man’s day in Monteros was devoted to telling jokes and playing pranks among other men. Many jokes expressed fears about the sexual power of women, in particular the ability of women to seduce and destroy their male victims. This research on masculinity demonstrates that “male” is not a stand-alone category but is always held in opposition to “female,” even when women are not present.

Other studies of masculinity have focused on the construction of masculinity through initiation rites, friendships, marriage, and fatherhood. Studying fatherhood among the Aka of central Africa, Barry Hewlett (1991) discovered that fathers in these communities are remarkably affectionate, attentive, and involved in the care of their children. Among families with young children, fathers spend 47 percent of their day within arm’s length of their children and frequently hold and care for them, especially in the evenings. Ethnographic research suggests that men are not “naturally” awkward or inept at childcare, nor are they less able to forge intimate and emotional bonds with their children. Rather, men are socialized to perform specific versions of fatherhood as proof of their masculine identities.

Beyond Male and Female

With the inclusion of masculinity, the anthropological study of gender came to be dominated by the opposed categories of male and female. Many studies took it as given that people are assigned at birth to one of these two categories and remain in their assigned category for a lifetime. A significant number of people in every culture, however, are not obviously male or female at birth, and some people do change their gender identities from one category to another—or even to an entirely different gender category that is neither male nor female. Over the past few decades, anthropological studies of gender have similarly broadened to consider those experiences as well.

Intersex and the Ambiguities of Identity

A friend tells you, “My sister just had a baby last night!” You respond, “Is it a boy or a girl?” Your friend replies, “Well, they don’t know. Maybe neither, maybe both.”

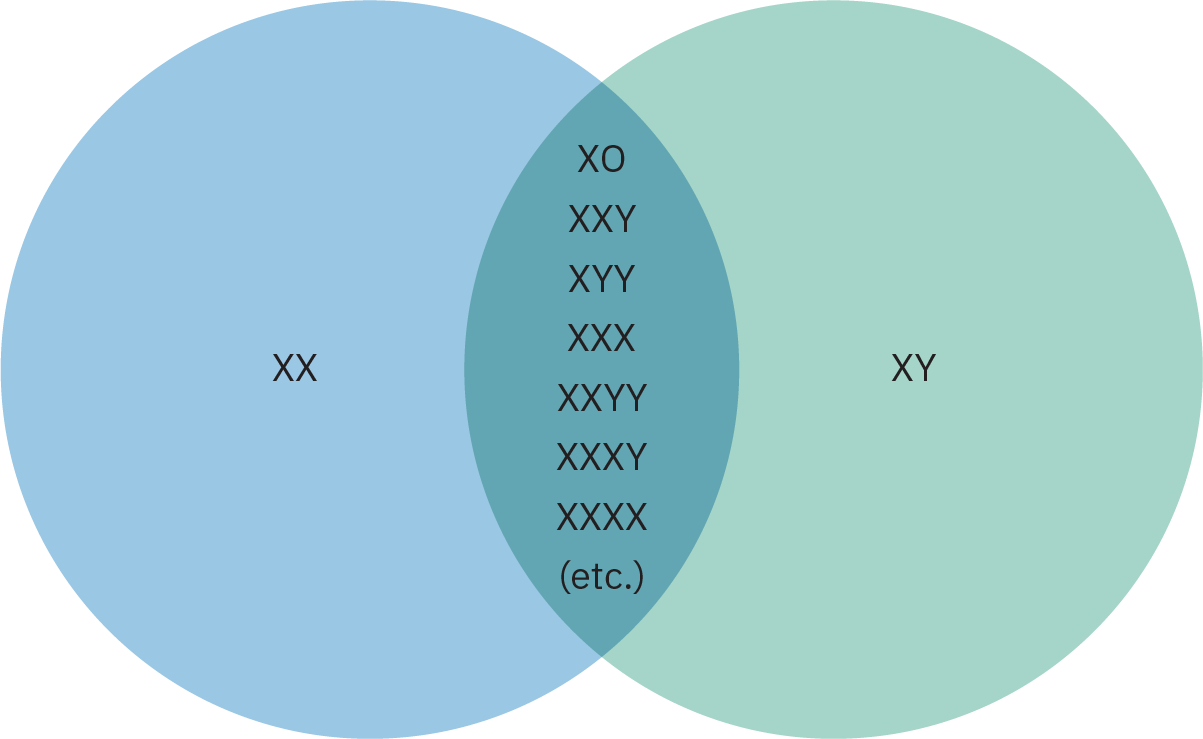

Based on a detailed analysis of extensive data, Anne Fausto-Sterling (2000) concluded that in about 1.7 percent of births, a baby’s sex cannot be completely determined just by glancing at the baby’s genitalia. (Note that due to different or changing considerations of sex determination, you may see different percentages or other differences in information; this text is using the most widely accepted and adopted research.) Intersex is an umbrella term for people who have one or more of a range of variations in sex characteristics or chromosomal patterns that do not fit the typical conceptions of male or female; the prefix inter– means “between” and refers here to an apparent biological state “between” male and female. There are many causal factors that can make a person intersex. Genetically, the baby may have a different number of sex chromosomes. Rather than two X chromosomes (associated with females) or one X and one Y chromosome (associated with males), babies are sometimes born with an alternative number of sex chromosomes, such as XO (only one chromosome) or XXY (three chromosomes). In other cases, hormonal activity or even chance occurrences in the womb can affect the baby’s anatomy.

While it is true that the majority of humans display biological characteristics associated with either one sex or another, 1.7 percent is not insignificant. If that percentage were applied to the global total of about 140 million babies born every year, it would mean that that more than two million of these babies could be intersex. On a more local level, if that percentage were applied to any town of 300,000 people, there could be more than 5,000 intersex people.

Beyond biology, the category of intersex reveals a great deal about the cultural mechanisms of gender. Intersexuality can be recognized at any point in a person’s life, from infancy to well into adulthood. Parents often discover their child is intersex in a medical context, such as at birth or during a subsequent visit to the pediatrician. When a doctor explains that a child is intersex, parents may be confused and concerned. Some doctors who are uncomfortable with biological sex ambiguity may order tests to determine the child’s chromosomal count and hormone levels and take measurements of the child’s genitals. They may urge parents to assign a specific gender to the baby and commit to plans for hormonal treatments and surgical interventions to affix that assigned gender to the growing child. Doctors are often taught to present the chosen gender as the “real” underlying sex of the baby, making medical treatment a process of allowing the baby’s “natural” (meaning unambiguous) sex to emerge. This conceptualization of intersex babies as “really” either male or female contradicts the complex mix of male and female traits presented by most intersex bodies.

Many intersex persons support a ban on what they call intersex genital mutilation, or IGM. In a 2017 article, Latinx intersex author and activist Hida Viloria calls attention to the hundreds of intersex people who have come forward to say that IGM has harmed them. The underlying goal of sexual assignment surgery, Viloria points out, is to create bodies capable of heterosexual sex and matching a gender binary. Medical ethicist Kevin Behrens (2020) argues that surgical interventions should only be carried out when surgery serves the best medical interests of the child and, in most cases, medical intervention should be delayed until the intersex person is old enough to give informed consent. Behrens also emphasizes that parents and children have the right to know the truth about an intersex child’s diagnosis and the possible consequences of any suggested treatment.

Intersex ambiguity and the rush to hide or eliminate it reveal important lessons about biology and culture. The process of determining what an intersex person was “meant to be” often involves a large set of biological variables, many of them subject to change over time. Those factors vary not only for intersex people but for everyone. Chromosomes alone do not make females and males. Rather, the interactions of genetic factors with hormones and environmental forces produce a complex continuum of gender. Instead of a binary of male and female separated by a hard boundary, many gender scholars recognize gender as a multidimensional spectrum of differences. There is far more biological variation within the cultural categories of male and female than between the two. This is not to deny the existence of biological differences but rather to complicate the concepts of sex and gender, allowing for the normalcy of ambiguity and the tolerance of variation.

Multiple Gender and Variant Gender

Many societies construct additional gender categories in addition male and female to accommodate people who do not fit into a binary gender system. The term multiple gender indicates a gender system that goes beyond male and female, adding one or more categories of variant gender to accommodate more sex/gender diversity. A variant gender is an added version of male or female that accommodates those who were not assigned to that category at birth but adopt that identity during the course of their lives. A person whose biology, identity, or sexual orientation contradicts their assigned sex/gender role can adopt a variant-gender identity. For instance, a person might be considered female at birth but later transition to a masculine version of female—what anthropologists term female variant.

Anthropologist Serena Nanda (2000) has studied variant-gender categories in many societies, including Native North American societies and peoples in Brazil, India, Polynesia, Thailand, and the Philippines. The widespread practice of multiple gender indicates a common cultural need to accommodate the complexities of human sex, gender, and sexuality. In contrast, European and Euro-American societies have inherited a rigid two-gender system that stigmatizes people who do not conform to the gender identity assigned to them at birth. Activists pressing for more gender flexibility can be inspired by examples of alternative gender in many non-European cultures.

When Spanish explorers first came to North America, they were astonished to find men in Native American societies who dressed as women, did the work of women, and had sexual relationships with men. Later, anthropologists who studied Native American groups discovered that some groups, including the Crow and the Navajo, had categories of variant male (assigned a male identity at birth but adopting a feminine identity later on) and variant female (assigned female at birth but adopting a masculine identity later on). Note that people in variant categories did not fully transition to the opposite gender but rather took on a masculine or feminine variant of the sex assigned at birth. Ignoring the Native American terms for variant gender, early European explorers referred to variant males as berdache, a Portuguese term that indicated a male prostitute—though that is not what they were at all. In 1990, as Native American LGBTQ people sought to resurrect their heritage of variant gender, they coined the pan-Indian term two-spirit, meaning people with both male and female spirits.

Two-spirit people were highly valued and esteemed in Native American cultures. Rather than facing stigma or rejection, their alternate gender identity was thought to give them special talents and spiritual powers. In many Native American societies, two-spirit people often became healers and spiritual leaders. They were typically very successful at performing the work of the opposite gender. Male-variant people were known for their excellent cooking and needlework, and many female-variant people were great hunters and warriors. Two-spirit people were also called upon to act as intermediaries between genders, such as in marriage arrangements.

Like gender-nonconforming people in many societies, two-spirit people began to realize their variant identities in childhood, rejecting the activities associated with their assigned gender. A boy might want to cook or weave, or a girl might prefer to hunt and play with the boys. If there were not enough boys to hunt, a family might even encourage a girl to develop a variant identity so that she could help provide meat to the family. Sometimes, children would experience visions or dreams guiding them to the tools associated with the opposite gender.

Generally speaking, people of variant gender had sexual relationships with people of the gender opposite their lived identity. So if a person took on the clothing and work of a woman, they would be expected to have intimate relationships with men, and people who lived as men would have relationships with women. Neither two-spirit people nor their opposite-gender partners were considered lesbian or gay.

With European colonization of North America came a much more restrictive system of gender categories and sexualities. As Euro-Americans expanded into Native American territories, Native Americans were pressured to assimilate to Euro-American norms. From 1860 to 1978, children were removed from their families and sent to assimilationist schools, where they were taught that Native cultures were backward and variant genders were sinful and deviant. By the 1930s, variant-gender practices had largely disappeared. However, with the rise of the American LGBTQ movement, many Native Americans have rediscovered the more flexible and tolerant gender system of their ancestors.

The Power of Gender: Patriarchy and Matriarchy

In cultural constructions of gender, two or more genders are defined in an overall system that assigns various forms of behavior and activity (and stereotypes!) to different categories or gendered realms of society. Some of those activities are considered more important than others, and some of those behaviors are more authoritative and dominant. Gender is not only a system of differences between the realms of female and male but also a system of power between those two realms.

Patriarchy: Ideology and Practice

Anthropologist Jennifer Hasty, reflects on what she learned about gender ideology while working as wedding videographer:

As a side gig to my anthropology job, I ran my own business as a wedding videographer in the Philadelphia metropolitan area from 2010 to 2017. While the whole venture was driven by economic necessity (I was teaching part-time), the wedding industry turned out to be a fascinating vantage point from which to view gender relations in American society. Most weddings were meticulously planned by the bride, with the groom deferring to her wishes or staying out of the whole process. Brides who were attracted to my artsy, minimalist film aesthetic tended to be middle-class professionals, college graduates heading into careers in education, finance, law, or medicine. Many of these weddings were grand potlatches of middle-class style and markers of identity.

The notion that a woman is passed from the paternalistic domain of her father into the care and supervision of her groom reflects a larger gender ideology about the relations between men and women in family life. A gender ideology is a coordinated set of ideas about gender categories, relations, behaviors, norms, and ideals. These ideas are embedded in the institutions of the family, the economy, politics, religion, and other sociocultural spheres. As with racial and class ideologies, people often challenge the explicit terms of a gender ideology while actively participating in the institutionalized forms associated with it. Though women have made great strides in American public life in past decades, in their weddings, they still enact a gender ideology that positions them as dependent objects passed between men in the transaction of marriage. The power of gender ideology is that it most frequently operates below the level of consciousness. An ideology that becomes naturalized as “common sense” becomes hegemonic.

Patriarchy is a widespread gender ideology that positions men as rulers of private and public life. Within the household, the eldest male is recognized as head of the family, organizing the activities of dependent women and children and governing their behavior. Family resources such as money and land are controlled by senior men. Men make decisions; women acquiesce. Beyond the family, men are accorded positions of leadership throughout society, and women are summoned to play a supportive and enabling role as marginalized subordinates.

Contemporary forms of patriarchy in American and European contexts are linked to the European development of capitalism in the 1600s. As economic activities moved out of households and into factories and offices, the household came to be defined as a private sphere, while the world of economic and political activities came to be called the public sphere. Women were assigned to the private sphere of family life, where they were expected to carry out nurturing roles as wives and mothers. Men not only governed the private sphere but also participated in the competitive and sometimes dangerous public sphere.

Different forms of patriarchy have emerged throughout the world. In India, the development of agriculture and the rise of the state resulted in the increasing subordination of women in patriarchal social institutions (Bonvillain 1995). Patriarchal ideology and social structure date back to the Vedic period (1500–800 BCE). In the Vedic communities of ancient India, men dominated economic and political life, and women were mostly excluded from these spheres. However, women could exercise some forms of authority as mothers in their households. Girl children, though not preferred, were generally treated well. Girls and boys both were educated and participated in religious activities. Female chastity and fidelity were highly valued, but women could engage in premarital sex without being shunned, and wives could divorce their husbands. Legally, however, daughters and wives were dependent on the men in their lives, who could make decisions on their behalf. A woman was not permitted to inherit property unless she was the only child. In the post-Vedic period, patriarchy was strengthened with the systematic codification of Hindu law. Patriarchy grew even more domineering, with the cultural spread of child marriage, wife-beating, female infanticide, and the disfigurement and ritual death of widows. When India came under Muslim rule in the 12th century, Islamic customs for veiling and secluding women further marginalized women in Hindu and Muslim communities alike.

Though contemporary India is a country of ethnic and religious diversity, patriarchy has become a dominant organizational force throughout Indian society. In rural areas, people often live in large extended family households structured by patrilineal descent. These families consist of a married couple, their sons and sons’ families, and their unmarried daughters. Men are recognized as heads of their households, exercising authority over their wives and children. Beginning in the 19th century, a reform movement called for the elimination of many patriarchal customs such as child marriage and sati (the ritual death of widows). Reformers, most of them elite men and women, encouraged the education of girl children and the legalization of inheritance for women. In response, sati became outlawed, widows were allowed to remarry, the marriage age was fixed at 12, and women were permitted to divorce, inherit, and own property. In the latter part of the 20th century, the Indian state passed laws to enhance women’s equality in many areas, including education, inheritance, and employment. Urban women in middle- and upper-class families have benefited from these reforms. However, in rural areas, many of the patriarchal customs outlawed by the state continue to be practiced.

Matriarchy: Ideology and (Not) Practice

As the term suggests, matriarchy means rule by senior women. In a matriarchal society, women would exercise authority throughout social life and control power and wealth. Like patriarchy, matriarchy is a gender ideology. Unlike patriarchy, however, matriarchy is not embedded in structures and institutions in any culture in the contemporary world. That is to say, it’s just an ideology—not a dominant one, and certainly not hegemonic.

While societies with patrilineal kinship systems are strongly patriarchal, societies with matrilineal kinship systems are not matriarchal. This is a common source of confusion. In matrilineal kinship systems, children primarily belong to their mother’s kin group, and inheritance passes through the maternal line. However, even in matrilineal societies, leadership is exercised by the senior men of the family. Instead of a woman’s husband, it is her brother or mother’s brother (her maternal uncle) who makes decisions about family resources and disciplines the behavior of family members. Scholars who theorize the existence of ancient matriarchies suggest that those societies were not only matrilineal but also dominated by the leadership of women as well as the values of fertility and motherhood.

Where are the matriarchies? Why is patriarchy so prevalent while matriarchy is nonexistent? Nobody really knows the answers to these questions. Some anthropologists think that pregnancy and childcare marginalized women, while men were freer to participate in cultural practices, technologies, and institutions. Others suggest that women’s reproductive power posed a threat to men. Patriarchy may have been developed as a system of subordination and control over the acknowledged power of women.

In the search for matriarchy, it could be that anthropologists and feminists are looking for the wrong thing. While anthropologists have not found societies in which women dominate and control men, there are plenty of examples of cultures in which women and men enjoy relative equality and freedom from sexual oppression and control.

Gender and Power in Everyday Life

Contemporary anthropologists who study gender pay little attention to hypothetical debates about the origins of patriarchy or the possible existence of ancient matriarchy. Rather, cultural anthropologists are interested in how people interact with the cultural norms and systematized practices of gender in their societies today. Gender is diffused throughout culture, embedded in systems of kinship, modes of subsistence, political leadership and participation, law, religion, and medicine. Anthropologists study how people move through these gendered realms in their everyday lives. They explore how identities and possibilities are shaped by the structures of gender as well as how people struggle against and sometimes transform gendered expectations.

Cultural anthropologists who study women in patriarchal cultures highlight the diversity of women’s experiences and their various techniques of asserting their interests in difficult circumstances. In her study of the problem of fistula among women in Niger, Allison Heller (2019) explores how women navigate gendered realms as they cope with a debilitating reproductive problem. Obstetric fistula is a complication of childbirth in which tissues separating the bladder from the vagina are ruptured, often resulting in chronic incontinence (uncontrolled urination). Often the result of prolonged or obstructed labor, fistula disproportionately affects women in rural and poor communities, who frequently give birth without professional medical assistance. The incontinence, pain, and reproductive complications of fistula stigmatize many of the women who have this condition. A host of global aid and relief agencies depict such women as victims of fistula, rejected by their husbands and ostracized by their communities. Heller’s ethnography complicates this simplistic picture. In her interviews with women affected by fistula, Heller discovered that family structures and relationships profoundly shape women’s experiences of fistula and the treatments available to them. In social and medical crises, these women turn to their mothers for support and advocacy. Mothers may insist that their daughters be brought to the hospital in cases of complicated labor, thereby preventing or mitigating the severity of fistula. Mothers may also act as intermediaries between women and their relatives and neighbors, working to reduce the stigma of fistula and promote sympathy and acceptance. Heller also found that marriage conditioned a woman’s experience of fistula. Whether her marriage was arranged or a marriage “for love,” a woman whose family supported her marriage was more likely to receive extended family support. Women who had strong relationships with their husbands were far less likely to be rejected by them after developing fistula.

The cultural anthropology of gender considers the situations people face as gendered persons and how they draw from available resources and relationships to fulfill their roles and sometimes challenge gendered expectations. Contemporary anthropologists of gender study, for instance, women’s experiences of migration, genocide, religious practice, and media, and men’s experiences of culture within the social construction of masculinity, among many other topics. A growing number of studies also focus on the experiences of trans, non-binary, and variable gender individuals, as will be discussed below.

Sexuality and Queer Anthropology

Intersecting with gender, the anthropological study of sexuality explores the diversity of meanings, practices, relationships, and experiences associated with erotic interactions. Since the 1980s, the study of sexuality in anthropology has burgeoned into the dynamic subfield of queer anthropology. Anthropologists working in this subfield focus on areas of sociocultural activity distinguished from the presumed norms of heterosexuality and binary gender identities.

Same-Sex and Queer Studies

Cultural anthropologists have long been fascinated with sexuality. Of central importance to marriage, kinship, and gender relations, sexuality also pervades art, religion, medicine, economics, and even politics in cultures around the world. As they documented sexuality and sexual practices in cultures around the world, anthropologists demonstrated the prevalence of same-sex erotic interactions.

British anthropologist E. E. Evans-Pritchard spent his early career studying social organization among two different African groups, the Azande and the Nuer. Later in his career, Evans-Pritchard began thinking about the many stories he had heard in the course of his years studying African societies, particularly stories describing the prevalence of same-sex erotic practices in Zande society in precolonial times. In an article on the topic, he describes how unmarried adult warrior men, unable to marry due to the scarcity of marriageable women and forbidden to engage in adultery with other men’s wives, often took younger men as sexual partners or “wives” (1970). The warrior paid bride wealth to the parents of the younger man and performed services to the young man’s family just as he would have to the natal family of a female wife. The partners took on the roles of husband and wife, and the younger men referred to themselves as women. As the Azande did not approve of anal sex, male partners had sex “between the thighs”—that is, the older man penetrating between the thigh gap of the younger one.

Like the men, Zande women also commonly engaged in same-sex practices and relationships. In Zande culture, men were permitted to have more than one wife and a husband took turns sleeping with each of his wives. In a family of several wives, then, a woman would wind up sleeping alone many nights. Zande men and women told Evans-Pritchard that lonely wives would often get together at night, and engaged in sexual activity. Women could also formalize a “love-friend” relationship in public, widely considered to be a cover for same-sex relations.

While some same-sex practices are ritualized in some cultures, others are more informal and less public. Some cultures construct same-sex practices as a phase associated with adolescent experimentation and tutelage. As in many parts of contemporary Africa, girls in boarding schools in Ghana are known to experiment with same-sex relationships. In Ghana, it’s called supi (possibly short for supervisor or superintendent). In boarding high schools, a senior girl might take a junior girl as a special friend (Dankwa 2009; Gyasi-Gyamera and Søgaard 2020). Some of these bonds are fairly casual. The junior girl runs errands for the senior girl, such as fetching water or food. The senior girl provides protection and help to the junior girl (such schools could be full of difficulties, including supply shortages and bullying). Some supi relationships can become emotionally and physically intense. The two girls often exchange gifts, write each other love letters, and fondle and caress one another. They might shower together or share a bed. Supi is not limited to a special category of girls (i.e., identified lesbians) but has been widespread among schoolgirls, nearly all of whom eventually marry men and fulfill their conventional roles as wives and mothers.

Many anthropological studies describe same-sex practices in societies that otherwise strongly value heterosexual marriage and fertility. In such contexts, sexuality is not so much an identity as it is a ritual, life stage, coping technique, or form of pleasure. Though sometimes shielded from public view, same-sex relations are seen as complementary to heterosexual relations in some cultural contexts, fully compatible with conventional demands for heterosexual marriage and family life. In his research on gender and sexuality in Nicaragua, for instance, Roger Lancaster (1992) found that conventionally masculine men could maintain their essentially heterosexual identities if they took the “active,” penetrative role in same-sex encounters.

With the progress of the LGBTQIA+ movement originating in the United States and western Europe, people around the world who engage in same-sex and transgender practices have formed public identities and communities, calling for the acceptance and legal recognition of their relationships. Rather than indulging in same-sex pleasures as a substitute for “the real thing” or as something done “on the side,” American gay and lesbian communities recast their own practices as “the real thing,” a set of practices and relationships central to their whole way of life. This assertion has profound implications for notions of family and community. If heterosexual marriage and reproduction form the foundation of kinship systems based on the idea of biological descent, then same-sex relationships suggest new forms of kinship based on networks and shared values. In Families We Choose (1991), anthropologist Kath Weston explores how lesbian and gay families in the San Francisco Bay Area constructed family networks that both reflected and challenged mainstream notions of family.

Transgender Studies

Evans-Pritchard’s research on male-male marriage among the precolonial Azande provided an example of young men who were socially constructed as women through their wifely role in these marriages. Across the continent, in West Africa, women in precolonial Igbo society could be ritually transformed into men and then engage in female-female marriages as husbands. In Male Daughters and Female Husbands (1987), Ifi Amadiume describes how a father with no sons could make his eldest daughter into an honorary “son” who could inherit and carry on the patrilineage. This woman became a “male daughter.” If she were married, she would return to her natal compound to undergo a ceremony that transferred her into the social category of male. She would then wear men’s clothes, live in the male section of the compound, perform men’s work rather than women’s, and participate in community life as a man. She could marry women who then became her wives (thus becoming a “female husband”). Those wives would have discreet liaisons with men in the area in order to bear children, who would belong to the lineage of the female husband. It was also possible for Igbo women who became wealthy and powerful in their communities to take a title through ritual means that allowed them to take wives of their own, just as male daughters could. Even if she were married herself, a powerful woman could have wives to do most or all of her domestic work. Did these powerful women have sexual relations with their wives? Anthropologists just don’t know. Amadiume describes women joking about sex between women in such marriages, but nobody knows how common it might have been.

Building on this earlier research, a fresh area of inquiry has developed in anthropology centered on the experiences, identities, and practices of transgender and gender-nonbinary persons and communities. Transgender describes a person who transitions from a gender category ascribed at birth to a chosen gender identity. Gender nonbinary describes a person who rejects strict male and female gender categories in favor of a more flexible and contextual expression of gender. Cultural anthropologists have described a great diversity in the expression of trans identities, pointing to the prevalence of transgender practices the world over.

Taking an innovative approach, anthropologist Marcia Ochoa (2014) devised a research project on “spectacular femininity” in Venezuela by examining two communities: female beauty pageant contestants and transgender sex workers who also hold beauty pageants. Ochoa traces the emergence of the beauty pageant in Venezuela and identifies this ritual competition as a carrier of notions of modernity and nationhood. She explores the competition of young women, or misses, in the Miss Venezuela pageant as well as the local and regional beauty pageants for transformistas, gay Venezuelans who identify as women. The stylized performances of transformistas carry over into their displays on Avenida Libertador in central Caracas, the neighborhood where they conduct their trade as sex workers. In order to compete in these realms of spectacular femininity, both misses and transformistas undergo painful surgical procedures to make their bodies conform to an exaggerated ideal of femininity.

Ochoa’s work is pathbreaking in its ability to bring together concepts often explored separately or held in opposition: heterosexuality and non-heterosexuality, gender and sexuality, and cis and trans identities (cisgender describes gender identity constructed on the sex assigned at birth). By juxtaposing misses and transformistas, she shows how these seemingly disparate concepts are threaded together in the complex web of Venezuelan culture.

The End of Gender?

In cultures that are strongly heteronormative with rigid two-gender systems, some people feel restricted in their gender identities and sexual practices. In many countries, efforts to create more flexibility in the expression of gender and sexuality have focused on gaining equal rights for and combating discrimination against women and LGBTQIA+ persons. In the past 50 years, this social movement has achieved great strides at national and global levels. In 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council passed a resolution recognizing LGBTQIA+ rights. The United Nations subsequently urged all countries to pass laws to protect LGBTQIA+ persons from discrimination, hate crimes, and the criminalization of non-heterosexuality. Same- sex marriage has now been legalized in 29 countries, including the United States, Canada, Mexico, Taiwan, and most of western Europe. In many countries, however, same-sex acts and gender nonconformity are still criminalized, sometimes punishable by death.

Where progress has been made on human rights for LGBTQIA+ persons, these changes have made life much easier for many people, allowing them to feel secure in their families, their jobs, and their public lives. Some activists are concerned that such legal reforms do not go far enough, however. Gender and sexuality are not just legal issues; they are cultural issues as well. The strict heterosexual two-gender scheme common to European and American cultures is a system infused with patriarchal values, expressed in patriarchal practices and institutions. That is to say, inequality is built into the heteronormative system of gender. In order to achieve true freedom and full equality, is it necessary to get rid of categories of gender and sexuality altogether? Are gender categories inherently oppressive?

Some people think so, arguing that society should transition to more gender-blind forms of language and social relations. In the United States, a movement is underway to neutralize gender in everyday language. Whereas masculine pronouns (he/him) were previously the default way of referring to hypothetical persons or situations where gender is not specified, followed by a movement toward specifying both masculine and feminine pronouns (he or she/him or her), new conventions call for the use of third-person plural forms (they/ them) as singular pronouns instead, particularly to include people who identify as neither man nor woman. Notably, this is already an accepted feature of everyday English that people commonly use without thinking about; if a housemate tells you, “Someone left a message for you,” you’re more likely to respond with “What did they want?” than with “What did he want?” or “What did he or she want?” Moreover, a convention is evolving that allows people to specify the pronouns they would prefer, either gendered (she/her, he/him) or neutral (they/them, other).

Will changes in pronoun usage bring about greater freedom and equality in patriarchal societies? Maybe. Many languages have gender-free pronouns, such as Twi, a West African language of the Akan people in central Ghana. However, though matrilineal, the Akans are also patriarchal. And gender is a very fundamental aspect of identity in Akan societies, structuring norms of dress, language, behavior, and relationships throughout a person’s life. In other words, pronouns do not bear much relationship to the organization of gender in culture and social institutions. In the United States, the English language pronoun system might change to be gender-neutral, but women and LGBTQIA+ people will still inhabit those cultural categories. Those categories will not just disappear.

Previous discussions of racial categories have addressed the fact that race is not a set of biological categories objectively found in nature. Rather, race, like gender, is socioculturally constructed. Even so, it is naive to pretend that race does not exist as a social reality that structures inequality in many societies. When people try to be “color blind,” they ignore the sociocultural reality of race and make it more difficult to recognize and remediate racial inequalities. Similarly, the fact that gender is a social construct does not mean that people can easily transition to a gender-blind society. Scholars of gender and sexuality argue that American society still grants forms of authority and privilege to heterosexual men through the cultural norms pervading public and private life. Asserting a “gender blind” perspective may obscure forms of inequality and violence that operate through gender and sexuality. Race and gender are both powerful sociocultural categories embedded in social practices and institutions. Anthropology encourages recognition of the diversity and complexity of those constructed categories alongside acknowledgment of the real histories of marginalization and struggle. Perhaps changes in pronoun use are just the beginning of more far-reaching changes to come.

|

OPTIONAL MINI-FIELDWORK ACTIVITY |

Consider your own body. What do you do to your body on a daily or weekly basis? Why? For two nonconsecutive days, make careful note of all of the routine practices devoted to your body (including hygiene, dress, exercise, etc.). Are these practices shaped by notions of gender? Of sex or sexuality? Do these practices shape the way you think of your body as gendered? Do they influence the way you present yourself in social situations? Do you think they influence the way others interact with you? Consider how other people respond to and interact with your body (or refuse to interact with it). How are these interactions shaped by cultural notions of gender and sexuality? Are there notions of power embedded in these bodily practices? Patriarchy? Feminism? Heteronormativity?

Marriage and Families across Cultures

As we have seen above, gender norms and ideologies play a significant role in shaping marriage practices. Because of the importance of marriage in creating socially sanctioned families, and thus reproducing cultural norms and gender roles, it is worth considering in greater detail.

Anthropological Definition of Marriage

Marriage is the formation of a socially recognized union. Depending on the society, it may be a union between a man and a woman, between any two adults (regardless of their gender), or between multiple spouses in polygamous societies. Marriages are most commonly established to provide a formal structure in which to raise and nurture offspring (whether biological or adopted/fostered), but not all marriages involve reproduction, and marriage can serve multiple functions. For instance, another function of marriage is to create alliances between individuals, families, and sometimes larger social networks. These alliances may provide political and economic advantages. While there are variations of marriage, the institution itself is, with a few notable exceptions, almost universal across cultures.

Marriage is an effective means of addressing several common challenges within families. It provides a structure in which to produce, raise, and nurture offspring. It reduces competition among and between males and females. And it creates a stable, long-term socioeconomic household in which the family unit can more adequately subsist with shared labor and resources. All societies practice rules of marriage that determine what groups an individual should marry into (endogamy rules) and which groups are considered off limits and not appropriate for marriage partners (exogamy rules). These rules are behavioral norms in a society. For example, in the United States, individuals tend to marry within the same generation (endogamy) and usually the same linguistic group, but they marry outside of very close kin (exogamy).

Across all cultures, there is an incest taboo, a cultural norm that prohibits sexual relations between parents and their offspring. This taboo sometimes extends to other relations considered too close for sexual relationship. In some societies, this taboo may extend to first cousins. In the United States, first-cousin marriage laws vary across states. French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss argued that the incest taboo is the original social structure because it naturally separates groups of people into two types—those with whom an individual has family ties (so-called biological ties) and those with whom an individual can have sexual relations and establish ties.

Defining marriage can be complex. In the southern Andes of Peru and Bolivia, Indigenous people begin marriage with a practice known as servinakuy (with spelling variations). In servinakuy, a man and woman establish their own independent household with very little formal social acknowledgement and live together until the birth of their first child, after which they are formally considered to be a fully married couple. Not a trial marriage and not considered informal cohabitation, servinakuy is, instead, a prolonged marriage process during which family is created over time. Andean legal scholars argue that these unions should carry with them the legal rights and protections associated with a formal marriage from the time the couple begins living together.

Like all social institutions, ideas about marriage can adapt and change. Within urban Western societies, the concept of marriage is undergoing a great deal of change as socioeconomic opportunities shift and new opportunities open up for women. In Iceland, in 2016, almost 70 percent of children were born outside of a marriage, usually to committed unmarried couples (Peng 2018). This trend is supported by national social policies that provide generous parental leave for both married individuals and those within a consensual union, but the change is also due to the more fluid nature of family today. As norms change in Iceland across generations, it will be interesting to see if the practiced form of consensual union we see today eventually comes to be considered a sanctioned form of marriage.

Forms of Marriage

Anthropologists group marriage customs into two primary types: a union of two spouses only (monogamy) or a union involving more than two spouses (polygamy). Monogamy is the socially sanctioned union of two adults. In some societies this union is restricted to a man and a woman, and in other societies it can be two adults of any gender. In June 2015, in Obergefell v. Hodges, the US Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage in the United States, following earlier legal recognitions in many other Western countries. Today, same-sex marriage is legal in 30 countries. While the movement to legalize same-sex marriage has been long and tumultuous in many of these countries, same-sex marriages and unions have historically played significant roles in both Indigenous and Western societies.

Serial monogamy is a form of monogamy in which adults have a series of two-person monogamous marriages over a lifetime. It is increasingly common in Western societies, but it is also practiced in some small-scale societies. In serial monogamy, divorce and remarriage are common.

Polygamy is the socially sanctioned union of more than two adults at the same time. In polygamous societies, families usually begin with a two-person marriage between a man and a woman. In some cases, the marriage will remain as a single couple for a long period of time or for the duration of their lives because of lack of resources or availability of partners. Adding partners is frequently a sign of status and is considered an ideal for families in polygamous societies. In some cases, too, polygamy is practiced to address extreme social stress due to things such as warfare or skewed population distributions caused by famine and high mortality rates.

There are two main kinds of polygamy, based on the partners involved, as multiple men and multiple women in a single marriage (called group marriage) is not common. Polygyny, which is the more common form of polygamy, is the marriage of one man to more than one woman. There is often marked age asymmetry in these relationships, with husbands much older than their wives. In polygynous households, each wife commonly lives in her own house with her own biological children, but the family unit cooperates together to share resources and provide childcare. The husband usually “visits” his wives in succession and lives in each of their homes at various times (or lives apart in his own). It is common, though not universal, for there to be a hierarchy of wives based on seniority. Polygyny is found worldwide and offers many benefits. It maximizes the family labor force and the shared resources and opportunities available for family members and creates wide kinship connections within society. Commonly in polygynous societies, larger families are afforded higher social status and they have stronger political and economic alliances.

The second main form of polygamy is polyandry. In polyandry, which is comparatively rare, there is one wife and more than one husband. Polyandrous marriages minimize population growth and may occur in societies where there is a temporary surfeit of males and scarcity of females or scarcity of resources. In fraternal polyandry, brothers marry a single wife. This is the most common in Nepal, where it is practiced by a minority of mainly rural families. Fraternal polyandry offers several benefits for societies like Nepal with scarce resources and dense population. Where there is extreme scarcity of land acreage, it allows brothers to share an inheritance of land instead of dividing it up. It reduces inequality within the household, as the family can thus collectively subsist on the land as a family unit. Also, in areas where land is scattered over large distances, it allows brothers to take turns living away from home to tend herds of animals or fields and then spending time at home with their shared wife. It also minimizes reproduction and population growth in a society where there is a very dense population, as the wife can carry only one pregnancy at a time.

Marriage Integrated with Family

Following marriage, a couple begins a new family and establishes a shared residence, whether as a separate family unit or as part of an already established family group. The social rules that determine where a newly married couple will reside are called postmarital residence rules and are directly related to the descent rules that operate in the society. These rules may be adapted due to extenuating circumstances such as economic need or lack of housing. In the United States today, for example, it is increasingly common for newly married couples to postpone the establishment of a separate household when work, schooling, or children create a need for familial support.

In all cultures, marriage is a consequential matter not only to the adults immediately involved, but also to their families and to the broader community. In societies that practice unilineal descent, the newly married couple moves away from one family and toward another. This creates a disadvantage for the family that has “lost” a son or daughter. For example, in a patrilineal society, while the wife will remain a member of her birth lineage (that of her father), her children and her labor will now be invested mostly in her husband’s lineage. As a result, in societies practicing unilineal descent, there is a marriage compensation from one family to the other for this perceived loss. Marriage compensation is the transfer of some form of wealth (in money, material goods, or labor) from one family to another to legitimize the marriage as a creation of a new social and economic household. It is not seen as payment for a spouse, but as recognition that the marriage and future children are part of one lineage rather than another. There are several forms of marriage compensation, each symbolically marked by specific cultural practices.