Leadership

What is Leadership?

In the context of business, leadership is the process of establishing a direction and guiding and motivating others toward the achievement of organizational goals. A leader can be anyone in an organization—regardless of position—who is able to influence others to act or follow.

Leadership vs. Management

What is the difference between management and leadership? Sometimes the terms are used almost interchangeably, but there can be important distinctions between them (Video 1). Leadership is primarily about establishing a direction and influencing others to follow. Management, on the other hand, is more about successfully administering the many complex details involved in an organization’s operations. Leadership pursues change and challenges the status quo, whereas management seeks to provide stability within existing structures and processes.

Both management and leadership are necessary approaches, and they often overlap with one another. In most settings, the role of a manager includes both leadership and management functions. Leadership skills are needed to set the vision, and management skills are needed to implement a plan to achieve that vision. Recognizing the difference between leadership and management, however, can help individuals focus on developing their skills in both arenas. In many cases, successful outcomes are most likely when strong leadership is paired with effective management.

Video 1: Leadership and Management. Closed captioning is available.

Leadership as a Process

Expanding on the definition above, leadership has also been described as a dynamic exchange relationship, built over time, between two or more people who are dependent on each another for goal attainment.[1] There are several key components to this relationship (Figure 1):

- Leader

- Followers

- The context, or situation

- The process itself

- Consequences, or outcomes

Across time, each component interacts with and influences the other components, and whatever consequences (such as leader-follower trust) are created influence future interactions. As any one of the components changes, so too will leadership.[2]

The Leader

A leader is an individual who take charge of or guides the activities of others. The leader is often the orchestrater of group activity and the person who sets the tone of the group so that it can move forward to attain its goals. Effective leadership helps individuals and groups achieve their goals by focusing on maintenance needs, or the need for individuals to fit and work together by having, for example, shared norms, as well as task needs, or the need for individuals and groups to make progress toward attaining the goal(s) that brought them together.

The Followers

Followers are not passive participants in the leadership process. It is, after all, the followers who determine the needs that the leader must fulfill. In addition, it is the followers who either reject leadership or accept acts of leadership by surrendering to the direction of the leader.

The followers’ skill sets and readiness to follow determine the style of leadership that will be most effective. For example, followers who perform at high levels tend to cause their leaders to play a less directive role. Followers who are novices or poor performers, on the other hand, tend to cause their leaders to be more directive in their leadership style.[3]

The Context

Situations make demands on individuals, and not all situations are the same. Context refers to the situation that surrounds a leader and their followers. For example:

- Is the task structured or unstructured?

- Are the goals clear or ambiguous?

- Is there agreement or disagreement about goals?

- Is there a body of knowledge that can guide task performance?

- Is the task boring? Frustrating? Intrinsically satisfying?

- Is the environment complex or simple, stable or unstable?

The above factors create different contexts within which leadership unfolds, and each factor places a different set of needs and demands on the leader and on the followers.

The Process

The leadership process is a complex, interactive, and dynamic working relationship between leader and followers. To the extent that leadership is the exercise of influence, part of the leadership process is captured by the surrender of power by the followers and the exercise of influence over the followers by the leader.[4] Thus, the leader influences the followers and the followers influence the leader, the context influences the leader and the followers, and both leader and followers influence the context.

The Consequences, or Outcomes

A number of outcomes or consequences of the leadership process unfold between leader, followers, and context. For example, at the group level, two outcomes are important:

- Have the group’s maintenance needs been fulfilled? That is, do members of the group get along with one another, do they have a shared set of norms and values, and have they developed a good working relationship? Have individuals’ needs been fulfilled as reflected in attendance, motivation, performance, satisfaction, citizenship, trust, and maintenance of the group membership?

- Have the group’s task needs been met? That is, has the group accomplished the work it set out to do? Has the group reached its goals or achieved its purpose?

Leader Emergence

As we attempt to understand what leadership is all about, it is worth noting that not all leadership is based on an official position. That is, the title and official role of an individual within an organization do not always correspond to actual leadership influence, and leadership influence can extend beyond the boundaries of a group or organization (Example 1).

Generally speaking, individuals who are assigned titles and positions of authority are expected to provide leadership. When a leadership role is officially recognized, it is known as formal leadership. Unfortunately, there are plenty of individuals who have formal leadership positions but do not actually provide strong leadership. This can leave groups or organizations lacking in direction and purpose.

However, there are also individuals who do not have official positions of leadership but who exhibit leadership qualities and practices. Such individuals help create vision and inspire and motivate others. When leadership is exhibited without an official position, it is known as informal leadership.

Example 1: Warren Buffett

Warren Buffett (Figure 2) has become one of the wealthiest individuals in the world through his leadership of the holding company, Berkshire Hathaway Inc.

As chairman, president, and CEO, Buffett is the obvious formal leader at Berkshire Hathaway, but his effective leadership is perhaps better demonstrated by the devoted following he has outside of the official structure of the company. Thousands of individuals read his annual shareholder letter and travel to hear him at Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meetings.

One of the easily identifiable reasons for this is his unparalleled success as an investor. However, there are also a number of key features of his leadership style that have strongly contributed to his effectiveness and influence with his followers.

One interesting element of Buffett’s approach is his “light touch” as a manager. One of his key tasks is to identify companies for purchase that he believes are well-managed and situated for success. As a rule, he buys only companies whose directors he trusts. Because he has confidence in them and their direction, he is happy to leave them to their work with as little interference as possible, which is a trait that appeals to many companies looking for a potential buyer.

Buffett is also a leader who presents a vision, stands firmly behind it, and inspires others to confidence and enthusiasm about that vision. His approach to investing is starkly different from that of many other investors. He emphasizes a deep understanding of companies and their industries, and urges the wisdom of buying proven companies and trusting in their long-term success. This approach contrasts sharply with an eager obsession to discover an unknown company that is about to explode in value and provide quick riches.

Buffett’s patient, steady approach to long-term investing has proven effective in the extreme, and many others have placed their confidence in Buffett’s message and vision. As an important ingredient in this vision-casting, many have attested to Buffett’s skill in presenting his approach with a great simplicity that enables his followers to understand the vision easily and deeply, inspiring further confidence.

Paths to Leadership

People typically come to leadership positions in one of two ways (Video 2). In some instances, people are put into positions of leadership through formal processes. For example, university-based ROTC programs and military academies (like West Point) formally prepare individuals to be leaders. In other instances, leaders are appointed or elected. These types of leaders are referred to as designated, or assigned, leaders.

Emergent leaders, on the other hand, arise from the dynamics and processes that unfold within and among a group of individuals as they endeavor to achieve a collective goal. Many leaders emerge out of the needs of a given situation. Different situations call for different configurations of knowledge, skills, and abilities. For example, a group often turns to the member who possesses the knowledge, skills, and abilities that the group requires to achieve its goals.[5] People surrender their power to individuals whom they believe will make meaningful contributions to attaining group goals.[6]

Video 2: Assigned Versus Emergent Leadership. Closed captioning is available.

Leadership Theories

Leadership has been widely studied, and numerous approach to and theories about leadership have been proposed over the years (Video 3).

Video 3: A Short Introduction to Leadership Theory. Closed captioning is available.

Many of the theories of leadership can be grouped into three broad categories: trait approaches, behavioral approaches, and contingency approaches. Each of these categories is summarized below.

Trait Approaches to Leadership

The earliest approaches to the study of leadership sought to identify characteristics, or traits, that distinguished leaders from non-leaders and effective leaders from ineffective leaders. Researchers found that some traits do, in fact, relate to leadership, such as intelligence (both mental ability and emotional intelligence) and personality (particularly extraversion and conscientiousness). However, trait-based approaches fell short in that they did not factor in situational factors that impact leadership.

Despite problems with trait approaches to leadership, trait-based findings can still be useful to managers and companies. The key to benefiting from the findings of trait researchers is to be aware that not all traits are equally effective in predicting leadership potential across all circumstances. Scholars now conclude that instead of trying to identify a few traits that distinguish leaders from non-leaders, it is important to identify the conditions under which different traits affect a leader’s performance.

Behavioral Approaches to Leadership

From trait-based approaches, researchers turned their attention to studying leader behaviors. What did effective leaders actually do? Which behaviors made them perceived as leaders? Which behaviors increased their success? Researchers identified task-oriented and people-oriented behaviors, with task-oriented behaviors leading primarily to leader effectiveness and people-oriented behaviors leading primarily to employee satisfaction. However, results from behavioral-based leadership research were inconsistent.

Behavioral approaches, similar to trait approaches, ultimately fell out of favor because they neglected the environment in which behaviors are demonstrated. Researchers had hoped they would identify behaviors that would consistently predict leadership effectiveness, but it may be unrealistic to expect that a given set of behaviors would work under all circumstances. It turns out that specifying the conditions under which key behaviors are effective may be a better approach.

Contingency Approaches to Leadership

After the disappointing results of trait and behavioral approaches, several scholars developed leadership theories that incorporated the role of the environment. Specifically, researchers started following a contingency approach to leadership: Rather than trying to identify traits or behaviors that would be effective under all conditions, they moved toward specifying the situations under which different leadership styles (discussed in the following section) would be effective. For example, situational leadership theory (discussed later in this chapter) specifies that leaders should adapt their leadership style to the development level of followers.

Leadership Styles

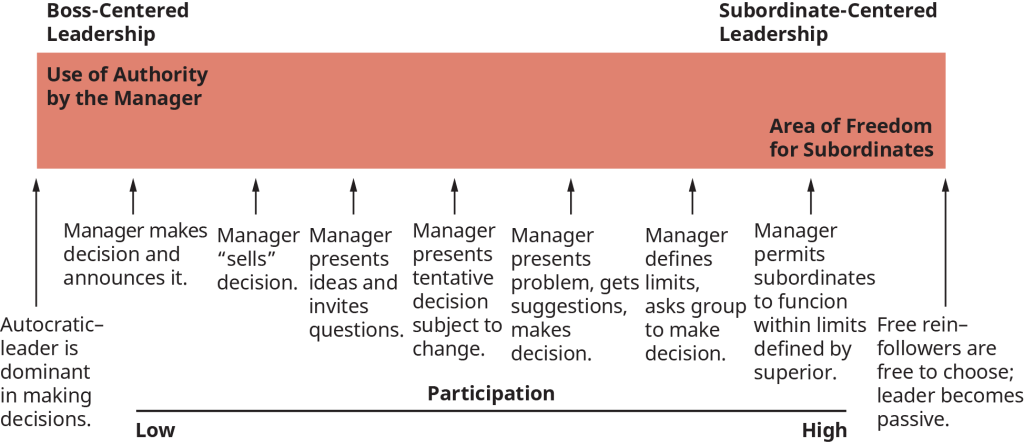

Individuals in leadership roles tend to be relatively consistent in the way they react to people and situations as well as how they attempt to influence the behavior of others. Such patterns of behavior are referred to as leadership styles. As Figure 3 shows, leadership styles can be placed on a continuum with an autocratic (boss-centered) style on one end and a free-rein (subordinate-centered) style on the other.[7]

Autocratic leaders are directive, allowing for very little input from subordinates. These leaders prefer to make decisions and solve problems on their own and expect subordinates to implement solutions according to very specific and detailed instructions. In this leadership style, information typically flows in one direction, from leader to subordinate. When autocratic leaders treat employees with fairness and respect, they may be considered knowledgeable and decisive. But often autocrats are perceived as heavy-handed in their unwillingness to share power, information, and decision-making.

At the opposite end of the continuum from an autocratic style is free-rein or laissez-faire (French for “leave it alone”) leadership. Leaders who use this style typically turn over all authority and control to subordinates. Employees are assigned a task and then given free rein to figure out the best way to accomplish it. The leader generally doesn’t get involved unless asked. Under this approach, subordinates often have unlimited freedom as long as they do not violate existing company policies.

While many subordinates might express a preference for a free-rein style, this approach can have several drawbacks. If free-rein leadership is accompanied by unclear expectations and lack of feedback from the leader, the experience can be frustrating for an employee. Employees may perceive the leader as being uninvolved and indifferent to what is happening or as unwilling or unable to provide the necessary structure, information, and expertise.

The trend in organizations today is away from the directive, controlling style of the autocratic leader. Instead, many businesses are looking for participative leaders, meaning leaders who share decision-making with group members and encourage discussion of issues and alternatives. Participative leadership falls between autocratic and free-rein leadership on the leadership-style continuum.

Employee Empowerment

Participative and free-rein leaders use a technique called empowerment to share decision-making authority with subordinates. Empowerment means giving employees increased autonomy and discretion to make their own decisions, as well as control over the resources needed to implement those decisions. When decision-making power is shared at all levels of the organization, employees feel a greater sense of ownership in, and responsibility for, organizational outcomes.

Use of employee empowerment is on the rise. This increased level of involvement comes from the realization that people at all levels in the organization possess unique knowledge, skills, and abilities that can be of great value to the company.

Situational Leadership

No leadership style is effective all the time. According to situational leadership[8] (Video 4), one of the most well-known contingency approaches to leadership, effective leaders select a leadership style that corresponds with the development level of followers.

Video 4: Introduction to the Situational Approach to Leadership. Closed captioning is available.

The situational leadership model (Figure 4 and Table 1) specifies four distinct styles or strategies of leadership, which are formed based on different combinations of directive (i.e., task-oriented) and supportive (i.e., relational-oriented) behaviors on the part of leaders. These are abbreviated with “S” for style. The model also specifies four distinct development levels of followers that emerge from different combinations of competency (i.e., knowledge, skills, and abilities) and commitment (i.e., motivation and confidence) levels of followers. These are abbreviated with “D” for development.

Employees who are at the earliest stages of development are seen as being highly committed but with low competence for the tasks. Thus, leaders should be highly directive, but there is less of a need for supportive behaviors. As employees become more competent but experiences disillusionment, leaders should continue to offer direction but should also engage in more supportive behaviors, an approach referred to as coaching. Supportive behaviors should continue while employees experience variable commitment, but the need for directive behaviors declines as employees gain competence. Finally, delegating is the recommended approach with employees who are both highly committed and highly competent, which involves low levels of both directive and supportive behaviors on the part of the leader.

| Development Level | Development Description | Leadership Level | Leadership Description |

| D1: Enthusiastic Beginner | Low competence with high commitment | S1: Directing | High direction with low support |

| D2: Disillusioned Learner | Some competence with low commitment | S2: Coaching | High direction with high support |

| D3: Capable but Cautious Performer | High competence with some commitment | S3: Supporting | Low direction with high support |

| D4: Self-reliant Achiever | High competence with high commitment | S4: Delegating | Low direction with low support |

Chapter Review

Optional Resources to Learn More

| Articles | |

| McKinsey Featured Insights: Getting Beyond the BS of Leadership Literature | |

| Harvard Business Review: Great Leaders Are Confident, Connected, Committed, and Courageous | |

| Harvard Business Review: The Fundamentals of Leadership Still Haven’t Changed | |

| Harvard Business Review: Understanding Leadership | |

| Books | |

| Leadership BS by Jeffrey Pfeffer | |

| Podcasts | |

| Wisdom from the Top | |

| Videos | |

| Leadership Models, Theories, and Tips(playlist) | |

| Harvard Business Review: What Makes a Great Leader? | |

| Introduction to Leadership (playlist) | |

| Leadership Concepts (playlist) | |

| Leadership Essentials (playlist) |

Chapter Attribution

Chapter 12 of Black, J. S. & Bright, D. S. (2019). Organizational behavior. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/12-introduction. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Chapter 6 of Gitman, L. J., McDaniel, C., Shah, A., Reece, M., Koffel, L., Talsma, B., & Hyatt, J. C. (2018). Introduction to business. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/introduction-business/pages/6-introduction. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Chapters 12 and 13 of Linabary, J. R. (2021, August 19). Small group communication. https://pressbooks.pub/smallgroup/. Licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Module 10 of Spencer, A. (n.d.). Principles of management. Lumen Learning. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-principlesofmanagement/chapter/what-is-leadership/. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Chapter 12 of of University of Minnesota. (2017). Organizational behavior. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/organizationalbehavior/part/chapter-12-leading-people-within-organizations/. Licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Media Attributions

Figure 1: Rice University. (2019, June 5). The leadership process. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/12-2-the-leadership-process. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2: USA International Trade Administration. (2015, April 17). Warren Buffett [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://bi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warren_Buffett#/media/File:Warren_Buffett_at_the_2015_SelectUSA_Investment_Summit.jpg. Public domain.

Figure 3: Rice University. (2019, June 5). Tannenbaum and Schmidt’s leadership continuum. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/12-3-leader-emergence. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4: Ftsn. (2019, February 18). Situational leadership. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Figure_of_Situational_Leadership.jpg. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Video 1: GreggU. (2020, April 13). Leadership and management. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/OZL5iy95T1w

Video 2: GreggU. (2020, April 10). Assigned versus emergent leadership. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/_tkij3_wOtM

Video 3: Simon Ash (The Right Questions). (2022, September 6). A short introduction to leadership theory (10 important models). [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/lti-4-QZmQc

Video 4: GreggU. (2020, May 20). Introduction to the situational approach to leadership [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/lonZyEVlf4U

- Hollander, E. P., & Julian, J. W. (1969). Contemporary trends in the analysis of leadership process. Psychological Bulletin, 7(5), 387–397. ↵

- Murphy, A. J. (1941). A study of the leadership process. American Sociological Review, 6, 674–687. ↵

- Greene, C. N. (1975). The reciprocal nature of influence between leader and subordinate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 187–193. ↵

- Hollander, E. P., & Julian, J. W. (1969). Contemporary trends in the analysis of leadership process. Psychological Bulletin, 7(5), 387–397. ↵

- Murphy, A. J. (1941). A study of the leadership process. American Sociological Review, 6, 674–687. ↵

- Smircich, L., & Morgan, G. (1982). Leadership: The management of meaning. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 18(3), 257–273. ↵

- Tannenbaum, R., & Schmidt, W. H. (1973). How to choose a leadership pattern. Harvard Business Review, 162–175. ↵

- Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1977). Management of organizational behavior: utilizing human resources (3d ed.). Prentice-Hall. ↵

The process of establishing a direction and guiding and motivating others toward the achievement of goals.

The process of guiding the development, maintenance, and allocation of resources to attain organizational goals.

Needs related to interpersonal interactions and relationships. For instance, a leader attending to maintenance needs may help manage conflict or decision-making by reducing tension and encouraging full participation.

Needs related to task completion or goal achievement. For instance, a leader attending to task needs may help analyze problems, distribute assignments, gather information, make sure everyone is heard from, keep the group focused, and facilitate the group reaching a consensus or final recommendations.

A leadership role that is officially recognized.

Leadership that is exhibited without an official position.

Leaders who are put into positions of leadership by formal processes; designated leaders also known as formal leaders.

Leaders who emerge from the dynamics and processes that unfold within and among a group of individuals as they endeavor to achieve a collective goal.

Boss-centered, directive leadership. Leaders who use this style prefer to make decisions and solve problems on their own, allowing for very little input from subordinates.

Subordinate-centered, hands-off leadership. Also called laissez-faire leadership. Leaders who use this style typically turn over all authority and control to subordinates.

Leaders who use this style share decision-making with group members and encourage discussion of issues and alternatives.

In individuals, autonomy and discretion to make their own decisions, as well as control over the resources needed to implement those decisions.

A theory of leadership in which effective leaders select a leadership style that matches the competency (i.e., knowledge, skills, and abilities) and commitment (i.e., motivation and confidence) levels of followers.