Organizational Structure and Design

Organizational Structure

Levels of Management: How Managers Are Organized

A typical organization has several layers of management. Think of these layers as forming a pyramid, with top managers occupying the narrow space at the peak, frontline managers the broad base, and middle managers the levels in between. As you move up the pyramid, management positions get more demanding, but they carry more authority and responsibility (along with more power, prestige, and pay). Top managers spend most of their time in planning and decision making, while frontline managers focus on day-to-day operations. For obvious reasons, there are far more people with positions at the base of the pyramid than there are at the other two levels.

In the interactive pyramid below, click each information icon to learn more about each level of management:

Let’s now look at each management level in more detail.

Top Managers

Top managers are responsible for the health and performance of the organization. They set the objectives, or performance targets, designed to direct all the activities that must be performed if the company is going to fulfill its mission. Top-level executives routinely scan the external environment for opportunities and threats, and they redirect company efforts when needed. They spend a considerable portion of their time planning and making major decisions. They represent the company in important dealings with other businesses and government agencies, and they promote it to the public. Job titles at this level typically include chief executive officer (CEO), chief financial officer (CFO), chief operating officer (COO), president, and vice president.

Middle Managers

Middle managers are in the center of the management hierarchy: they report to top management and oversee the activities of frontline managers. They’re responsible for developing and implementing activities and allocating the resources needed to achieve the objectives set by top management. Common job titles include operations manager, division manager, plant manager, and branch manager.

Frontline Managers

Frontline managers supervise employees and coordinate their activities to make sure that the work performed throughout the company is consistent with the plans of both top and middle management. It’s at this level that most people acquire their first managerial experience. The job titles vary considerably but include such designations as manager, group leader, office manager, foreman, and supervisor.

Structure Elements

Building an organizational structure engages managers in two key activities: job specialization (dividing tasks into jobs) and departmentalization (grouping jobs into units). Organizational structure outlines the various roles within an organization, which positions report to which, and how an organization will departmentalize its work. Take note than an organizational structure is an arrangement of positions that’s most appropriate for a company at a specific point in time. Given the rapidly changing environment in which businesses operate, a structure that works today might be ineffective in the future. That’s why you hear so often about companies restructuring—altering existing organizational structures to become more competitive once conditions have changed. Let’s now look at how the processes of specialization and departmentalization are accomplished.

Specialization

Organizing activities into clusters of related tasks that can be handled by certain individuals or groups is called specialization. This aspect of designing an organizational structure is twofold:

- Identify the activities that need to be performed in order to achieve organizational goals.

- Break down these activities into tasks that can be performed by individuals or groups of employees.

Specialization has several advantages. First and foremost, it leads to efficiency. Imagine a situation in which each department is responsible for paying its own invoices; a person handling this function a few times a week would likely be far less efficient than someone whose job is to pay all the bills. In addition to increasing efficiency, specialization results in jobs that are easier to learn and roles that are clearer to employees. But specialization has disadvantages, too. Doing the same thing over and over sometimes leads to boredom and may eventually leave employees dissatisfied with their jobs. Before long, companies may notice decreased performance and increased absenteeism and turnover (the rate at which workers who leave an organization and must be replaced).

Departmentalization

The second aspect of designing an organizational structure is departmentalization—grouping specialized jobs into meaningful units. Depending on the organization, they may be called divisions, departments, units, or groups. Traditional groupings of jobs result in different organizational structures, and for the sake of simplicity, we’ll focus on two key types—functional and divisional organizations.

Functional Organizations

A functional organization groups together people who have comparable skills and perform similar tasks. This form of organization is fairly typical for small to medium-size companies, which group their people by business functions: accountants are grouped together, as are people in finance, marketing and sales, human resources, production, and research and development. Each unit is headed by an individual with expertise in the unit’s particular function. Examples of typical functions in a business enterprise include human resources, operations, marketing, and finance.

There are a number of advantages to the functional approach. The structure is simple to understand and enables the staff to specialize in particular areas; everyone in the marketing group would probably have similar interests and expertise. But homogeneity also has drawbacks: it can hinder communication and decision making between units and even promote interdepartmental conflict. The marketing department, for example, might butt heads with the accounting department because marketers want to spend as much as possible on advertising, while accountants want to control costs.

Divisional Organizations

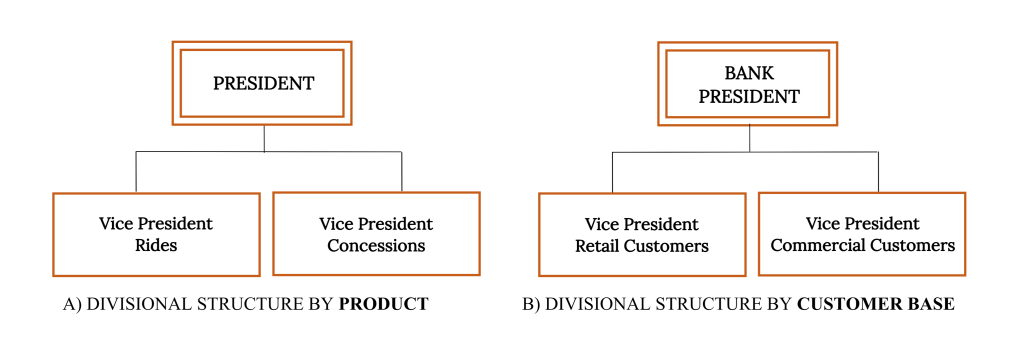

Large companies often find it unruly to operate as one large unit under a functional organizational structure. Sheer size can make it difficult for managers to oversee operations and serve customers. To rectify this problem, many large companies are structured as divisional organizations. Divisions are commonly formed according to products, customers, or geography.

Divisions are similar in many respects to stand-alone companies, except that certain common tasks, like legal work, tends to be centralized at the headquarters level. Each division functions relatively autonomously because it contains most of the functional expertise (production, marketing, accounting, finance, human resources) needed to meet its objectives. The challenge is to find the most appropriate way of structuring operations to achieve overall company goals.

There are pros and cons associated with divisional organization. On the one hand, divisional structure usually enhances a firm’s ability to respond to changes in the environment. On the other hand, services are often duplicated across units, resulting in higher costs. In addition, some companies have found that divisions tend to focus on their own needs and goals at the expense of the organization as a whole.

Product Divisions

Product division means that a company is structured according to its product lines. General Motors, for example, has four product-based divisions: Buick, Cadillac, Chevrolet, and GMC.[1] Each division has its own research and development group, its own manufacturing operations, and its own marketing team. This allows individuals in the division to focus all their efforts on the products produced by their division. A downside is that it results in higher costs as corporate support services (such as accounting and human resources) are duplicated in each of the four divisions.

Customer Divisions

Some companies prefer a customer division structure because it enables them to better serve their various categories of customers. For example, prior to announcing a split in 2021, Johnson & Johnson’s 200 or so operating companies were grouped into three customer-based business segments: consumer business (personal-care and hygiene products sold to the general public), pharmaceuticals (prescription drugs sold to pharmacies), and professional business (medical devices and diagnostics products used by physicians, optometrists, hospitals, laboratories, and clinics).[2]

Geographical Divisions

Geographical division enables companies that operate in several locations to be responsive to customers at a local level. Adidas, for example, is organized according to the regions of the world in which it operates (Figure 1). They have eight different regions, and each one reports its performance separately in their annual reports.[3]

The Organizational Chart

Once an organization has set its structure, it can represent that structure in an organizational chart: a diagram delineating the interrelationships of positions within the organization.

Let’s look at the chart of an organization that relies on a divisional structure based on goods or services produced—say, a theme park. The top layers of this company’s organization chart might look like the one in Figure 2A. We see that the president has two direct reports—a vice president in charge of rides and a vice president in charge of concessions. What about a bank that’s structured according to its customer base? The bank’s organization chart would begin like the one in Figure 2B. Once again, the company’s top manager has two direct reports, in this case a VP of retail-customer accounts and a VP of commercial-customer accounts.

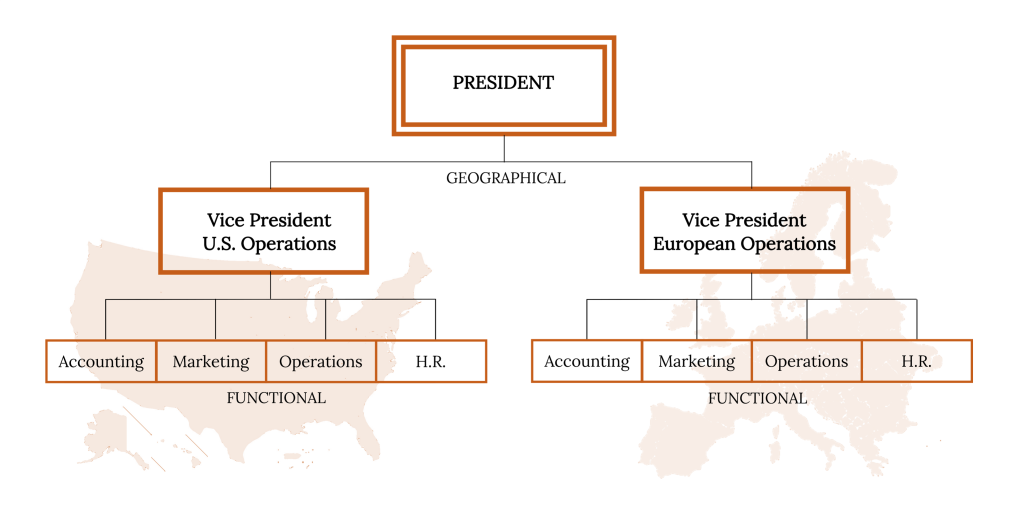

Over time, companies revise their organizational structures to accommodate growth and changes in the external environment. It’s not uncommon, for example, for a firm to adopt a functional structure in its early years. Then, as it becomes bigger and more complex, it might move to a divisional structure—perhaps to accommodate new products or to become more responsive to certain customers or geographical areas. Some companies might ultimately rely on a combination of functional and divisional structures. This could be a good approach for a credit card company that issues cards in both the United States and Europe. An outline of this firm’s organization chart might look like the one in Figure 3.

Chain of Command

The vertical connecting lines in the organization chart show the firm’s chain of command: the authority relationships among people working at different levels of the organization. That is to say, they show who reports to whom. When you’re examining an organization chart, you’ll probably want to know whether each person reports to one or more supervisors: to what extent, in other words, is there unity of command? To understand why unity of command is an important organizational feature, think about it from a personal standpoint. Would you want to report to more than one boss? What happens if you get conflicting directions? Whose directions would you follow?

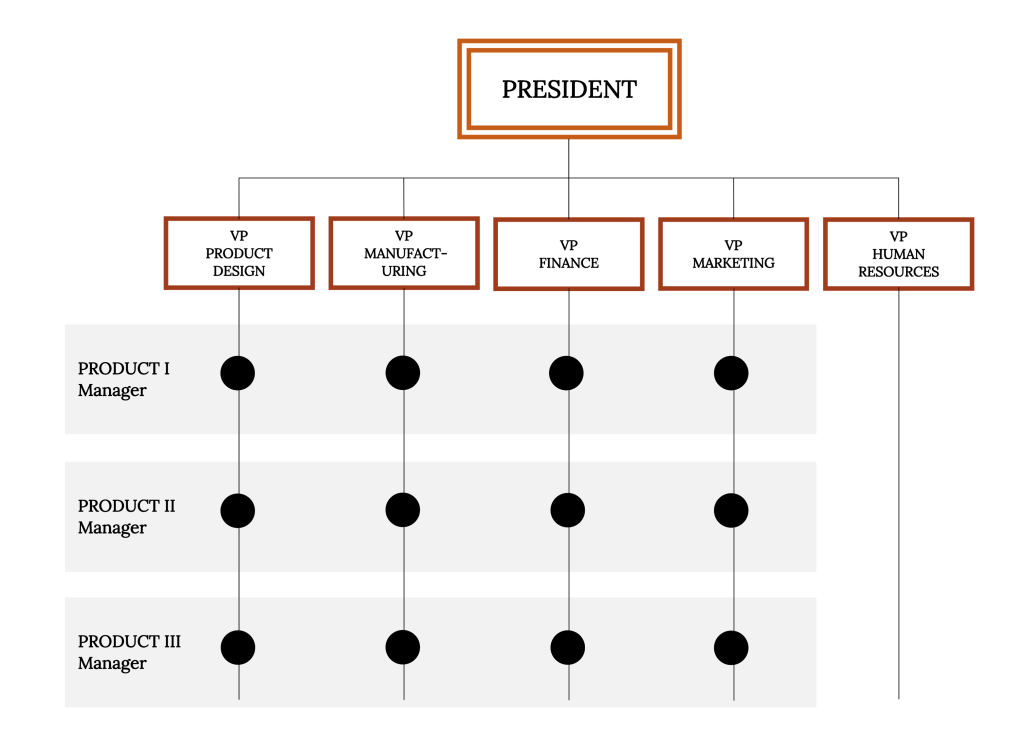

There are, however, conditions under which an organization and its employees can benefit by violating the unity-of-command principle. Under a matrix structure, for example, employees from various functional areas (product design, manufacturing, finance, marketing, human resources, etc.) form teams to combine their skills in working on a specific project or product. This matrix organization chart might look like the one in Figure 4.

Consider an athletic footwear company that uses a matrix structure. To design new products, the company may create product teams made up of designers, marketers, and other specialists with expertise in particular sports categories—say, running shoes or basketball shoes. Each team member would be evaluated by both the team manager and the head of his or her functional department.

Span of Control

Another important characteristic of a firm’s chain of command is the number of layers between the highest and lowest managerial levels. Typically, new organizations have only a few layers of management—an organizational structure that’s often called flat.

As a company grows, however, it tends to add more layers between the top and the bottom; that is, it gets taller. Added layers of management can slow down communication and decision making, causing the organization to become less efficient and productive. That’s one reason why many organizations often restructure to become flatter.

There are trade-offs between the advantages and disadvantages of flat and tall organizations. Companies determine which trade-offs to make according to a principle called span of control, which measures the number of people reporting to a particular manager. If, for example, you remove layers of management to make your organization flatter, you end up increasing the number of people reporting to a particular supervisor.

So what’s better—a narrow span of control (with few direct reports) or a wide span of control (with many direct reports)? The answer to this question depends on a number of factors, including frequency and type of interaction, proximity of subordinates, competence of both supervisor and subordinates, and the nature of the work being supervised. For example, you’d expect a much wider span of control at a nonprofit call center than in a hospital emergency room.

Delegating Authority

Given the tendency toward flatter organizations and wider spans of control, how do managers handle increased workloads? They must learn how to handle delegation—the process of entrusting work to subordinates. Unfortunately, many managers are reluctant to delegate. As a result, they not only overburden themselves with tasks that could be handled by others, but they also deny subordinates the opportunity to learn and develop new skills.

Centralization and Decentralization

If and when a company expands, it has to decide whether most decisions should still be made by individuals at the top or delegated to lower-level employees. The first option, in which most decision making is concentrated at the top, is called centralization. The second option, which spreads decision making throughout the organization, is called decentralization.

Centralization has the advantage of consistency in decision-making. Since in a centralized model, key decisions are made by the same top managers, those decisions tend to be more uniform than if decisions were made by a variety of different people at lower levels in the organization. In most cases, decisions can also be made more quickly provided that top management does not try to control too many decisions. However, centralization has some important disadvantages. If top management makes virtually all key decisions, then lower-level managers will feel under-utilized and will not develop decision-making skills that would help them become promotable. An overly centralized model might also fail to consider information that only front-line employees have or might actually delay the decision-making process. Consider a case where the sales manager for an account is meeting with a customer representative who makes a request for a special sale price; the customer offers to buy 50 percent more product if the sales manager will reduce the price by 5 percent for one month. If the sales manager had to obtain approval from the head office, the opportunity might disappear before she could get approval—a competitor’s sales manager might be the customer’s next meeting.

An overly decentralized decision model has its risks as well. Imagine a case in which a company had adopted a geographically-based divisional structure and had greatly decentralized decision making. In order to expand its business, suppose one division decided to expand its territory into the geography of another division. If headquarters approval for such a move was not required, the divisions of the company might end up competing against each other, to the detriment of the organization as a whole. Companies that wish to maximize their potential must find the right balance between centralized and decentralized decision making.

The Organizational Life Cycle

Most organizations begin as very small systems that feature very loose structures. In a new venture, nearly every employee might contribute to many aspects of an organization’s work. As the business grows, the workload increases, and more workers are needed. Naturally, as the organization hires more and more people, employees being to specialize. Over time, these areas of specialization mature through differentiation, the process of organizing employees into groups that focus on specific functions in the organization. Usually, differentiated tasks should be organized in a way that makes them complementary, where each employee contributes an essential activity that supports the work and outputs of others in the organization.

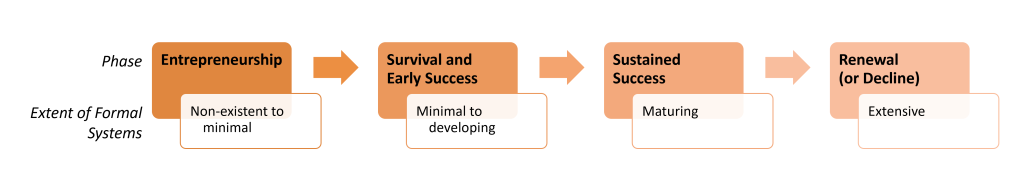

The patterns and structures that appear in an organization need to evolve over time as an organization grows or declines, often through four predictable phases (Figure 5). In the entrepreneurship phase, the organization is usually very small and agile, focusing on new products and markets. The founders typically focus on a variety of responsibilities, and they often share frequent and informal communication with all employees in the new company. Employees enjoy a very informal relationship, and the work assignments are very flexible. Usually, there is a loose, organic organizational structure in this phase.

The second phase, survival and early success, occurs as an organization begins to scale up and find continuing success. The organization develops more formal structures around more specialized job assignments. Incentives and work standards are adopted. The communication shifts to a more formal tone with the introduction of hierarchy with upper- and lower-level managers. It becomes impossible for every employee to have personal relationships with every other employee in the organization. At this stage, it becomes appropriate to introduce structures that support the formalization and standardization required to create effective coordination across the organization.

In a third phase, sustained success or maturity, the organization expands and the hierarchy deepens, now with multiple levels of employees. Lower-level managers are given greater responsibility, and managers for significant areas of responsibility may be identified. Top executives begin to rely almost exclusively on lower-level leaders to handle administrative issues so that they can focus on strategic decisions that affect the overall organization. At this stage, structures of the organization are strengthened.

A transition to the fourth phase, renewal or decline, occurs when an organization expands to the point that its operations are complex and need to operate somewhat autonomously. At times it becomes necessary for the organization to be reorganized or restructured to achieve higher levels of coordination between and among different groups or subunits. Managers may need to address fundamental questions about the overall direction and administration of the organization.

To summarize, the key insight about the organizational life cycle is that the needs of an organization will evolve over time. Different structures are needed at different stages as an organization develops. The needs of employees will also change. An understanding of the organizational life cycle provides a framework for thinking about changes that may be needed over time.

Organizational Design

While organizational structure forms the backbone of any organization, it represents just one dimension of a more comprehensive concept: organizational design. Organizational design encompasses not only structure but also strategic objectives, information and reward systems, management and decision-making processes, human resources, and organizational culture—all of which contribute to an organization’s ability to operate, adapt, and thrive.

Specifically, organizational design “refers to the “deliberate arrangement of key components within an organization to achieve collective goals efficiently and effectively.”[4] Put simply, organization design is about “how to organize people and resources to collectively accomplish desired ends.”[5]

One well-known framework for organizational design is the Star Model, which provides a structured foundation for companies to guide their design choices and address potential misalignments among organizational components (Figure 6).[6] The model consists of five elements—strategy, structure, processes, rewards, and people—that form the points of a star, with alignment at the center linking these interconnected components. According to the Star Model, each design element should be consistent and mutually reinforcing, creating a cohesive and effective organizational design.

Strategy

Strategy represents an organization’s plan and direction for achieving goals, delivering value to customers, and gaining a competitive advantage. Key questions to guide strategic design include: What are the strengths and weaknesses of the organization in relation to factors at play in the external environment? What superior organizational capabilities can be developed and used to create a competitive advantage for the organization? Organizational capabilities are the unique combination of skills, processes, technologies, and human abilities that differentiate an organization. Competitive advantage is the ability to attract more customers, earn more profit, or return more value to shareholders than rival firms do. In short, strategy serves as the foundation of the design process, establishing priorities that shape how the other design elements are organized.[7]

Structure

Structure determines where decision-making authority resides within the organization, encompassing specialization, departmentalization, chain of command, and centralization. Essential questions for structuring include: What roles are responsible for key goals? Who reports to whom? Who participates in decision-making? Structure influences how tensions within the organization are addressed and shapes how goals are tackled, whether collaboratively or within distinct groups.[8],[9] On the one hand, a hierarchical, centralized structure enforces goals through top-down control but can hinder agility; on the other hand, a flatter, decentralized structure fosters innovation and quick decision-making but may lead to inefficiencies or a lack of alignment in large or complex organizations.[10]

Processes

Processes refer to systematic ways to manage information, tasks, and resources within an organization. Important questions related to processes include: How are resources allocated? How does information move within the organization? What mechanisms exist to enable collaboration both internally and externally? Processes ensure that the necessary communication channels and resources are in place to support efficient coordination and decision-making.

Rewards

Rewards encompass systems that motivate and guide behavior toward organizational goals. Questions to consider for reward systems include: How is individual and team progress tracked and assessed? How do rewards encourage attention to organizational priorities? Effective reward systems align employee efforts with company goals, motivating productivity and engagement. With a variety of reward tools available, companies must choose those best suited to their unique objectives and needs.[11]

People

The people element of the Star Model includes employee mindsets, skillsets, and relevant human resource policies. Companies should consider the following questions: What mindsets and skills are critical for success, and how can they be developed? What new talent is required, and how will existing talent be nurtured to align with organizational goals? This element ensures that the organization has the human capital needed to advance its mission and adapt to evolving needs.

Alignment

Alignment across design elements is crucial in the Star Model: “For an organization to be effective, all the policies must be aligned and interact harmoniously with one another.”[12] The connections between strategy, structure, processes, rewards, and people reinforce one another, creating a cohesive system that supports organizational goals.[13] Key alignment questions include: Are the five design elements consistent, interdependent, and mutually reinforcing? Are there any areas where inconsistencies may hinder effectiveness?

Organizational Design: In Summary

Organizational design is concerned with the factors and issues that must be considered with respect to the development, implementation, and maintenance of an effective organization. The goal of the Star Model (Video 1) is to reinforce that organizational design does not stop with structure and that an effective organization cannot exist without ensuring that the core design elements have been analyzed and configured in a manner that best positions the organization to achieve its stated mission and goals.

Video 1: Star Model of Organizational Design. Closed captioning is available.

Chapter Review

Optional Resources to Learn More

| Articles | |

| Harvard Business Review: The Importance of Organizational Design and Structure | |

| Harvard Business Review: Do You Have a Well-designed Organization? | |

| Jay Galbraith: Star Model | |

| strategy + business: 10 Principles of Organizational Design | |

| The New York Times: In Business, ‘Flat’ Structures Rarely Work. Is There a Solution? | |

| Books | |

| Designing Organizations: Strategy, Structure, and Process at the Business Unit and Enterprise Levels by Jay R. Galbraith | |

| Leading Organization Design: How to Make Organization Design Decisions to Drive the Results You Want by Gregory Kesler and Amy Kates |

|

| Videos | |

| Essential Topics in Organizational Design (playlist) | |

| The HR Hub: Principles of Organizational Design |

Chapter Attribution

This chapter incorporates material from the following sources:

Chapter 10 of Bright, D. S. & Cortes, A. H. (2019). Principles of management. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/10-introduction. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Carballo, R. E. (2023). Purpose-driven transformation: a holistic organization design framework for integrating societal goals into companies. Journal of Organization Design, 12(4), 195-215. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41469-023-00156-8. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Gutterman, A. S. (2023). Organizational Design. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4541482. Licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Chapter 9 of Skripak, S. J. & Poff, R. (2023). Fundamentals of business (4th ed.). VT Publishing. https://pressbooks.lib.vt.edu/fundamentalsofbusiness4e/chapter/chapter-9-structuring-organizations/. Licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Media Attributions

Figure 1: Grey, K. (2022). Adidas’ geographical divisions. https://archive.org/details/9.2_20220623. Licensed with CC BY 4.0. Data from https://www.annualreports.com/HostedData/AnnualReports/PDF/OTC_ADDDF_2021.pdf. Added Adidas Logo from WikimediaCommons (public domain) and BlankMap-World-Continents-Coloured by Max Naylor from WikimediaCommons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Figure 2: Gray, K. (2022). Organizational charts for divisional structures. https://archive.org/details/9.4_20220623. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3: Gray, K. (2022). Organizational charts for functional and divisional structures. https://archive.org/details/9.5_20220623. Licensed with CC BY 4.0. Includes https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blank_map_of_the_United_States.PNG and https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Europe_blank_map.png (GNU General Public license).

Figure 4: Gray, K. (2022). Matrix structure. https://archive.org/details/9.6_20220623. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5: Hoopes, C. (2023). Formalization across the organizational life cycle. Licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 6: Hoopes, C. (2024). Star Model of organizational design. Licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Video 1: Organizational Design Videos. (2018, October 1). Star model of organizational design [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/LXanu2hpE5s

- Associated Press (2010, October 7). General Motors rebuilds with 4 divisions. Augusta Chronicle. http://chronicle.augusta.com/life/autos/2010-10-07/general-motors-rebuilds-4-divisions# ↵

- Pound, J., & Kopecki, D. (2021, November 12). J&J plans to split into two companies, separating consumer products and pharmaceutical businesses. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/11/12/jj-shares-jump-after-ceo-says-health-giant-plans-to-break-up-in-wsj-report.html ↵

- adidas. (n.d.). Headquarters. Retrieved August 14, 2023, from https://www.adidas-group.com/en/about/headquarters/ ↵

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/organizational-design ↵

- Greenwood, R., & Miller, D. (2010). Tackling design anew: Getting back to the heart of organizational theory. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(4), 78-88. ↵

- Galbraith, J. R. (2014). Designing organizations: Strategy, structure, and process at the business unit and enterprise levels. John Wiley & Sons. ↵

- Galbraith, J. R. (2014). Designing organizations: Strategy, structure, and process at the business unit and enterprise levels. John Wiley & Sons. ↵

- Battilana, J., & Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing–Insights from the study of social enterprises. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 397-441. ↵

- Pratt, M. G., & Foreman, P. O. (2000). Classifying managerial responses to multiple organizational identities. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 18-42. ↵

- Hales, C. (1999). Leading horses to water? The impact of decentralization on managerial behaviour. Journal of Management Studies, 36(6), 831-851. ↵

- Kaplan, S., & Henderson, R. (2005). Inertia and incentives: Bridging organizational economics and organizational theory. Organization Science, 16(5), 509-521. ↵

- Galbraith, J. R. (2014). Designing organizations: Strategy, structure, and process at the business unit and enterprise levels. John Wiley & Sons. ↵

- Kates, A. (2015). Organization Design that Transforms. Practicing Organization Development: Leading Transformation and Change, 313-320. ↵

The highest level of management which is responsible for setting objectives; scanning the environment for opportunities and threats; and planning and decision making.

Managers who report to top management and oversee the activities of frontline managers. Their responsibilities include allocating resources and developing and implementing activities.

Managers at the lowest level of management who report to middle managers; they coordinate activities, supervise employees, and are involved in day-to-day operations.

the various roles within an organizational, which positions report to which, and how an organization will departmentalize its work

Altering existing organizational structures to become more competitive once conditions have changed.

Organizing activities into clusters of related tasks that can be handled by certain individuals or groups.

The rate at which workers who leave an organization and must be replaced.

Grouping specialized jobs into meaningful units.

A form of departmentalization that groups together people who have comparable skills and perform similar tasks.

A form of departmentalization in which each division contains most of the functional areas (production, marketing, accounting, finance, human resources); in other words, divisions are similar to stand-alone companies, and they function relatively autonomously.

A divisional departmentalization based on product lines.

A divisional departmentalization based on customer segments.

A divisional departmentalization based on geographical location.

A diagram delineating the interrelationships of positions within the organization.

The authority relationships among people working at different levels of the organization.

Occurs when each employee reports to only one supervisor.

A form of departmentalization that combines elements of functional and divisional structures.

In organizational structure, when an organization has only a few layers of management.

In organizational structure, when an organization has many layers of management.

The number of people reporting to a particular manager.

A span of control with few direct reports.

A span of control with many direct reports.

The process of entrusting work to subordinates.

In organizational structure, where decision making is concentrated at the top of the organizational hierarchy.

In organizational structure, where decision making is delegated to lower-level employees.

The deliberate arrangement of key components within an organization to achieve collective goals efficiently and effectively.

A framework for organizational design that contains five components: strategy, structure, processes, rewards, and people.

An organization’s plan and direction for achieving goals, delivering value to customers, and gaining competitive advantage.

The unique combination of skills, processes, technologies, and human abilities that differentiate an organization.

The ability to attract more customers, earn more profit, or return more value to shareholders than rival firms do.

Systematic ways to manage information, tasks, and resources within an organization.

Systems that motivate and guide behavior toward organizational goals.

Employee mindsets, skillsets, and relevant human resource policies.