Many forces influence the communities of living organisms present in different parts of the biosphere (all of the parts of Earth inhabited by life). The biosphere extends into the atmosphere (several kilometers above Earth) and into the depths of the oceans. Despite its apparent vastness to an individual human, the biosphere occupies only a minute space when compared to the known universe. Many abiotic forces influence where life can exist and the types of organisms found in different parts of the biosphere. The abiotic factors influence the distribution of biomes: large areas of land with similar climate, flora, and fauna.

Biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the geographic distribution of living things and the abiotic factors that affect their distribution. Abiotic factors such as temperature and rainfall vary based mainly on latitude and elevation. As these abiotic factors change, the composition of plant and animal communities also changes. For example, if you were to begin a journey at the equator and walk north, you would notice gradual changes in plant communities. At the beginning of your journey, you would see tropical wet forests with broad-leaved evergreen trees, which are characteristic of plant communities found near the equator. As you continued to travel north, you would see these broad-leaved evergreen plants eventually give rise to seasonally dry forests with scattered trees. You would also begin to notice changes in temperature and moisture. At about 30 degrees north, these forests would give way to deserts, which are characterized by low precipitation.

Moving farther north, you would see that deserts are replaced by grasslands or prairies. Eventually, grasslands are replaced by deciduous temperate forests. These deciduous forests give way to the boreal forests found in the subarctic, the area south of the Arctic Circle. Finally, you would reach the Arctic tundra, which is found at the most northern latitudes. This trek north reveals gradual changes in both climate and the types of organisms that have adapted to environmental factors associated with ecosystems found at different latitudes. However, different ecosystems exist at the same latitude due in part to abiotic factors such as jet streams, the Gulf Stream, and ocean currents. If you were to hike up a mountain, the changes you would see in the vegetation would parallel those as you move to higher latitudes.

Ecologists who study biogeography examine patterns of species distribution. No species exists everywhere; for example, the Venus flytrap is endemic to a small area in North and South Carolina. An endemic species is one which is naturally found only in a specific geographic area that is usually restricted in size. Other species are generalists: species which live in a wide variety of geographic areas; the raccoon, for example, is native to most of North and Central America.

Species distribution patterns are based on biotic and abiotic factors and their influences during the very long periods of time required for species evolution; therefore, early studies of biogeography were closely linked to the emergence of evolutionary thinking in the eighteenth century. Some of the most distinctive assemblages of plants and animals occur in regions that have been physically separated for millions of years by geographic barriers. Biologists estimate that Australia, for example, has between 600,000 and 700,000 species of plants and animals. Approximately 3/4 of living plant and mammal species are endemic species found solely in Australia. A wallaby (Wallabia bicolor), on the left in the image below, is a medium-sized member of the kangaroo family that is a pouched mammal, or marsupial (photo credit: (credit: modification of work by Derrick Coetzee;). The echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus), on the right in the image below, is an egg-laying mammal (photo credit: modification of work by Allan Whittome)

Sometimes ecologists discover unique patterns of species distribution by determining where species are not found. Hawaii, for example, has no native land species of reptiles or amphibians, and has only one native terrestrial mammal, the hoary bat. Most of New Guinea, as another example, lacks placental mammals.

Plants can also be specialists or generalists: specialist plants need specific conditions and resources and are often found in limited areas. Endemic species are a specific type of specialists that are found only in specific, often isolated, regions of the Earth, while generalists are found on many regions. Generalists are also able to use a wider range of resources or tolerate a wider range of conditions. Isolated land masses- such as Australia,

Hawaii, and Madagascar—often have large numbers of endemic plant species. Some of these plants are endangered due to human activity The forest gardenia (Gardenia brighamii), shown on the right, for instance, is endemic to Hawaii; only an estimated 15–20 trees are thought to exist. This tree is listed as federally endangered and is found only in five of the Hawaiian Islands in small populations consisting of a few individual specimens ( photo credit: Forest & Kim Starr). Some of the primary factors that control the geographic distributions of species include energy sources, temperature and water.

Hawaii, and Madagascar—often have large numbers of endemic plant species. Some of these plants are endangered due to human activity The forest gardenia (Gardenia brighamii), shown on the right, for instance, is endemic to Hawaii; only an estimated 15–20 trees are thought to exist. This tree is listed as federally endangered and is found only in five of the Hawaiian Islands in small populations consisting of a few individual specimens ( photo credit: Forest & Kim Starr). Some of the primary factors that control the geographic distributions of species include energy sources, temperature and water.

Energy Sources

Energy from the sun is captured by green plants, algae, cyanobacteria, and photosynthetic protists. These organisms convert solar energy into the chemical energy needed by all living things. Light availability can be an important force directly affecting the evolution of adaptations in photosynthesizers. For instance, plants in the understory of a temperate forest are shaded when the trees above them in the canopy completely leaf out in the late spring. Not surprisingly, understory plants have adaptations to successfully capture available light. One such adaptation is the rapid growth of spring ephemeral plants such as the spring beauty shown below. These spring flowers achieve much of their growth and finish their life cycle (reproduce) early in the season before the trees in the canopy develop leaves (photo credit: John Beetham).

In aquatic ecosystems, the availability of light may be limited because sunlight is absorbed by water, plants, suspended particles, and resident microorganisms. Toward the bottom of a lake, pond, or ocean, there is a zone that light cannot reach. Photosynthesis cannot take place there and, as a result, a number of adaptations have evolved that enable living things to survive without light. For instance, aquatic plants have photosynthetic tissue near the surface of the water; for example, think of the broad, floating leaves of a water lily—water lilies cannot survive without light. In environments such as hydrothermal vents, some bacteria extract energy from inorganic chemicals because there is no light for photosynthesis.

Inorganic Nutrients

Inorganic nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, are also important in the distribution and the abundance of living things. Most terrestrial plants and many aquatic plants obtain these inorganic nutrients from the soil or sediment when water moves into the plant through the roots. Therefore, soil structure (particle size of soil components), soil pH, and soil nutrient content play an important role in the distribution of plants. Animals obtain inorganic nutrients from the food they consume. Therefore, animal distributions are related to the distribution of what they eat. In some cases, animals will follow their food resource as it moves through the environment.

The availability of nutrients in aquatic systems is also an important factor. Many organisms sink to the bottom of the ocean when they die in the open water; when this occurs, the energy found in that living organism is sequestered for some time unless ocean upwelling occurs.

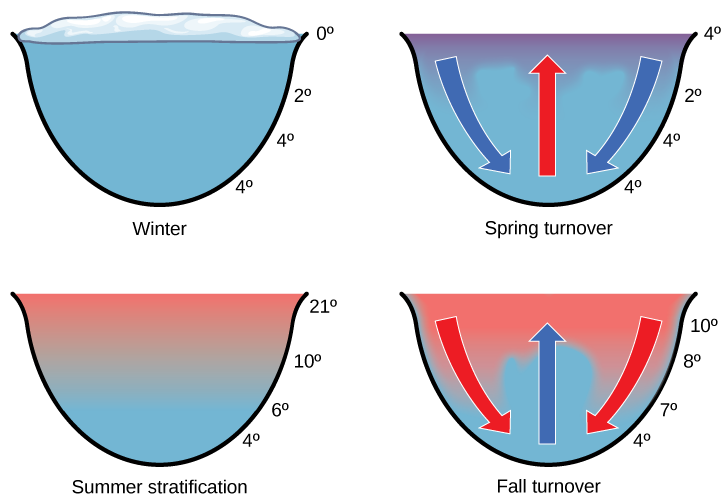

Ocean upwelling is the rising of deep ocean waters that occurs when prevailing winds blow along surface waters near a coastline. As the wind (green arrows) pushes ocean waters offshore, water from the bottom of the ocean (red arrows) moves up to replace this water. As a result, the nutrients once contained in dead organisms become available for reuse by other living organisms.In freshwater systems, the recycling of nutrients occurs in response to air temperature changes. The nutrients at the bottom of lakes are recycled twice each year: in the spring and fall turnover. The spring and fall turnover, shown below, is a seasonal process that recycles nutrients and oxygen from the bottom of a freshwater ecosystem to the top of a body of water. These turnovers are caused by the formation of a thermocline: a layer of water with a temperature that is significantly different from that of the surrounding layers. In wintertime, the surface of lakes found in many northern regions is frozen. However, the water under the ice is slightly warmer, and the water at the bottom of the lake is warmer yet at 4 °C to 5 °C (39.2 °F to 41 °F). Water is densest at 4 °C; therefore, the deepest water is also the densest. The deepest water is oxygen poor because the decomposition of organic material at the bottom of the lake uses up available oxygen that cannot be replaced by means of oxygen diffusion into the water due to the surface ice layer.

Ocean upwelling is the rising of deep ocean waters that occurs when prevailing winds blow along surface waters near a coastline. As the wind (green arrows) pushes ocean waters offshore, water from the bottom of the ocean (red arrows) moves up to replace this water. As a result, the nutrients once contained in dead organisms become available for reuse by other living organisms.In freshwater systems, the recycling of nutrients occurs in response to air temperature changes. The nutrients at the bottom of lakes are recycled twice each year: in the spring and fall turnover. The spring and fall turnover, shown below, is a seasonal process that recycles nutrients and oxygen from the bottom of a freshwater ecosystem to the top of a body of water. These turnovers are caused by the formation of a thermocline: a layer of water with a temperature that is significantly different from that of the surrounding layers. In wintertime, the surface of lakes found in many northern regions is frozen. However, the water under the ice is slightly warmer, and the water at the bottom of the lake is warmer yet at 4 °C to 5 °C (39.2 °F to 41 °F). Water is densest at 4 °C; therefore, the deepest water is also the densest. The deepest water is oxygen poor because the decomposition of organic material at the bottom of the lake uses up available oxygen that cannot be replaced by means of oxygen diffusion into the water due to the surface ice layer.

In springtime, air temperatures increase and surface ice melts. When the temperature of the surface water begins to reach 4 °C, the water becomes heavier and sinks to the bottom (blue arrows). The water at the bottom of the lake is then displaced by the heavier surface water and rises to the top (red arrow). As that water rises to the top, the sediments and nutrients from the lake bottom are brought along with it. During the summer months, the lake water stratifies, or forms layers, with the warmest water at the lake surface. This makes the layering of the water very stable because the warm surface waters are the least dense and the density increases and the temperature decreases with depth.

As air temperatures drop in the fall, the temperature of the lake water cools to 4 °C; therefore, this causes fall turnover as the heavy cold water sinks and displaces the water at the bottom. The oxygen-rich water at the surface of the lake then moves to the bottom of the lake, while the nutrients at the bottom of the lake rise to the surface. During the winter, the oxygen at the bottom of the lake is used by decomposers and other organisms requiring oxygen, such as fish.

Temperature

Temperature affects the physiology of living things as well as the density and state of water. Temperature exerts an important influence on living things because few living things can survive at temperatures below 0 °C (32 °F) due to metabolic constraints. It is also rare for living things to survive at temperatures exceeding 45 °C (113 °F); this is a reflection of evolutionary response to typical temperatures. Enzymes are most efficient within a narrow and specific range of temperatures; enzyme degradation can occur at higher temperatures. Therefore, organisms either must maintain an internal temperature or they must inhabit an environment that will keep the body within a temperature range that supports metabolism. Some animals have adapted to enable their bodies to survive significant temperature fluctuations, such as seen in hibernation or reptilian torpor. Similarly, some bacteria are adapted to surviving in extremely hot temperatures such as geysers. Such bacteria are examples of extremophiles: organisms that thrive in extreme environments.

Temperature can limit the distribution of living things. Animals faced with temperature fluctuations may respond with adaptations, such as migration, in order to survive. Migration, the movement from one place to another, is an adaptation found in many animals, including many that inhabit seasonally cold climates. Migration solves problems related to temperature, locating food, and finding a mate. In migration, for instance, the Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea) makes a 40,000 km (24,000 mi) round trip flight each year between its feeding grounds in the southern hemisphere and its breeding grounds in the Arctic Ocean. Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) live in the eastern United States in the warmer months and migrate to Mexico and the southern United States in the wintertime. Some species of mammals also make migratory forays. Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) travel about 5,000 km (3,100 mi) each year to find food. Amphibians and reptiles are more limited in their distribution because they lack migratory ability. Not all animals that can migrate do so: migration carries risk and comes at a high energy cost.

Some animals hibernate or estivate to survive hostile temperatures. Hibernation enables animals to survive cold conditions, and estivation allows animals to survive the hostile conditions of a hot, dry climate. Animals that hibernate or estivate enter a state known as torpor: a condition in which their metabolic rate is significantly lowered. This enables the animal to wait until its environment better supports its survival. Some amphibians, such as the wood frog (Rana sylvatica), have an antifreeze-like chemical in their cells, which retains the cells’ integrity and prevents them from bursting.

Water

Water is required by all living things because it is critical for cellular processes. Since terrestrial organisms lose water to the environment by simple diffusion, they have evolved many adaptations to retain water.

- Plants have a number of interesting features on their leaves, such as leaf hairs and a waxy cuticle, that serve to decrease the rate of water loss via transpiration.

- Freshwater organisms are surrounded by water and are constantly in danger of having water rush into their cells because of osmosis. Many adaptations of organisms living in freshwater environments have evolved to ensure that solute concentrations in their bodies remain within appropriate levels. One such adaptation is the excretion of dilute urine.

- Marine organisms are surrounded by water with a higher solute concentration than the organism and, thus, are in danger of losing water to the environment because of osmosis. These organisms have morphological and physiological adaptations to retain water and release solutes into the environment. For example, Marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus), sneeze out water vapor that is high in salt in order to maintain solute concentrations within an acceptable range while swimming in the ocean and eating marine plants.

Other Aquatic Factors

Some abiotic factors, such as oxygen, are important in aquatic ecosystems as well as terrestrial environments. Terrestrial animals obtain oxygen from the air they breathe. Oxygen availability can be an issue for organisms living at very high elevations, however, where there are fewer molecules of oxygen in the air. In aquatic systems, the concentration of dissolved oxygen is related to water temperature and the speed at which the water moves. Cold water has more dissolved oxygen than warmer water. In addition, salinity, current, and tide can be important abiotic factors in aquatic ecosystems.

Other Terrestrial Factors

Wind can be an important abiotic factor because it influences the rate of evaporation and transpiration. The physical force of wind is also important because it can move soil, water, or other abiotic factors, as well as an ecosystem’s organisms.

Fire is another terrestrial factor that can be an important agent of disturbance in terrestrial ecosystems. Some organisms are adapted to fire and, thus, require the high heat associated with fire to complete a part of their life cycle. For example, the jack pine—a coniferous tree—requires heat from fire for its seed cones to open (Figure). Through the burning of pine needles, fire adds nitrogen to the soil and limits competition by destroying undergrowth.

Abiotic Factors Influencing Plant Growth

Temperature and moisture are important influences on plant production (primary productivity) and the amount of organic matter available as food (net primary productivity). Net primary productivity is an estimation of all of the organic matter available as food; it is calculated as the total amount of carbon fixed per year minus the amount that is oxidized during cellular respiration. In terrestrial environments, net primary productivity is estimated by measuring the aboveground biomass per unit area, which is the total mass of living plants, excluding roots. This means that a large percentage of plant biomass which exists underground is not included in this measurement. Net primary productivity is an important variable when considering differences in biomes. Very productive biomes have a high level of aboveground biomass.

Annual biomass production is directly related to the abiotic components of the environment. Environments with the greatest amount of biomass have conditions in which photosynthesis, plant growth, and the resulting net primary productivity are optimized. The climate of these areas is warm and wet. Photosynthesis can proceed at a high rate, enzymes can work most efficiently, and stomata can remain open without the risk of excessive transpiration; together, these factors lead to the maximal amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) moving into the plant, resulting in high biomass production. The aboveground biomass produces several important resources for other living things, including habitat and food. Conversely, dry and cold environments have lower photosynthetic rates and therefore less biomass. The animal communities living there will also be affected by the decrease in available food.

Impacts on biodiversity

The factors discussed above all affect whether or not an individual species can live in an area and the overall productivity in the area. Biogeography also examines broad patterns in species richness, the number of different species in an area, and three main patterns appear.

The latitudinal diversity gradient

The latitudinal diversity gradient (LDG) is the global pattern of increased species richness in the tropics that decreases moving towards the poles. This patterns is seen for a wide-range of organisms and is a widely accepted pattern in ecology. However, the cause of this pattern is not widely agreed upon. In 2017, Schemske and Mittlebach[1] reviewed the main hypotheses suggested to explain the LDG. Many of these hypotheses had been summarized in a 1966 paper by Eric Pianka[2] The most widely supported theory is that the greater diversity in the tropics is due to a longer time for species to evolve and immigrate in the tropics because the higher latitudes have experienced glacial periods. When Pianka reviewed the hypotheses about the LDG, most of them were based on species interactions, but as ecological understanding has improved, most of the more recent hypotheses are based on evolution (Schemske and Mitlebach 2017). Regardless of the cause, the global pattern of increased species richness near the tropics is clear. For example, the map below shows the distribution of vertebrate animals on land with the red color indicating higher species richness and the blue colors representing lower species richness. This figure (CC BY 3.0) is from a research paper by Mannion et al 2104[3] which also presents a theory for evolutionary causes of the LDG.

Mannion et al (2014) categorize the hypothesis about the cause of the LDG as hypotheses that propose that the tropics could have higher diversity because of higher rates of speciation in the tropics, because of lower rates of extinction or because of a combination of the two. On a broader scale, Mannion et al (2014) classify explanations of the LDG as those based on the area of the tropics, the time available for evolution (as discussed above) or the energy available from sunlight and the lower seasonality in the tropics. While agreement about the causes of the LDG does not exist, Mannion et al’s (2014) examination of the fossil record indicates that climate (solar energy and low seasonality variability) is a dominant factor.

The elevation diversity gradient

The elevation diversity gradient is a trend towards greater species richness at middle elevations. In some ways, this gradient is not surprising because elevation is often used as a proxy for latitude in research because temperature tends to decrease with higher elevation and latitude. However, the elevational diversity gradient is much less studied.

The species-area relationship

Finally, repeated research has shown that the number of species is related to the area studied. This relationship is so strong, that it can be represented mathematically. In general, the number of species (S) in an area (A) can be estimated using an equation, one of the most common of which is

S= cAz

Z is the slope of a log-log graph of number of species (S), area (A) and c, a constant used depending on the unit of area used (and actually used in other ways too). Given that we just discussed trends in biodiversity with latitude and elevation, the conclusion that Z is not the same in all regions seems obvious. Z also varies depending on the type of species studied, in particular how easily the species can disperse.

One common application of the species-area relationship is in island biogeography. This theory, developed by Robert MacArthur and E. O. Wilson, explains species richness on islands as a combination of the number of species that reach the island and the number of species that go extinct on the island. In general, islands that are close to the mainland will have higher rates of species reaching the island and smaller islands will have higher rates of species extinction for the same number of species on the island. For all islands, the rate of species extinction increases as more species settled the islands. The theory predicts an equilibrium state at which the rate of species immigrating to the island equals the rate of species extinction. This theory has been useful in predicting a sort of steady-state species richness on islands and in more recent years has been expanded to include evolutionary processes at longer time scales. The graph below is a pictorial version of the theory (F.W., CC BY-SA 3.0 DE <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en>, via Wikimedia Commons).

The video below from the California Academy of Sciences gives a great overview of why species are not distribute evenly.