Chapter 12: Play and Peer Relationships

Social Cognition and Theory of Mind

Social Cognition and Theory of Mind

Social Cognition

When you see the two terms “social” and “cognition” together, you can probably figure out what the topic of this chapter means. Also, since this text is oriented around a sociocultural perspective, by this time, I am sure that you may have a hard time even thinking about cognition — or thinking — outside of a social context.

So that would be correct, but the term social cognition is actually a technical term meant to signify some pretty specific ideas in children’s thinking. Instead of it being “thinking in a social context,” as we have been discussing all along, it is “the intersection between social understanding and thinking.”

It will take more than a single phrase to explain it, though, and you will come to understand social cognition better as we go through some of the major categories of thinking it involves.

As an overview, social cognition encompasses:

- The mind: we all have one and can think

- Perspective-taking: different people can have different thoughts

- Metacognitive awareness: being aware of mental processes (i.e., attention, memory, problem-solving, etc.)

Video 12.1 What is social cognition?

Social cognition relates somewhat to Piaget’s idea of egocentrism, which occurs in his sensorimotor stage. So, while we have not gone into detail about his stages, this idea of egocentrism is helpful here because, in some ways, it is the polar opposite of social cognition!

When a young child is unable to see or imagine others’ perspectives, that child is in the egocentric stage. This is not a value judgment — it does not mean the child is selfish or egotistical. Instead, it means that the child can only view the world from their own standpoint, simply because they have not yet even defined the parameters of their and others’ thoughts and intentions. They act according to their own understanding, and that understanding does not extend to others in complex ways until later in childhood.

When Piaget identified social cognition in his work, he talked about young children past the egocentric stage; typically, five-year-old children are thought to “have developed social cognition.” But we know from other scholarly work that much younger children exhibit different types of thinking about others’ perspectives and using others as a means of development — even if they do not engage in a complex type of perspective-taking that many Western researchers have tested in laboratories.

Theory of Mind

Theory of mind refers to one’s ability to think about other people’s thoughts and to perceive and interpret other people’s behavior in terms of their mental states. This mental “mind reading” helps humans to understand and predict the reactions of others, thus playing a crucial role in social development. Infants and toddlers have a relatively simple theory of mind. They are aware of some basic characteristics: what people are looking at is a sign of what they are paying attention to; people act intentionally and are goal directed; people have positive and negative feelings in response to things around them; and people have different perceptions, goals, and feelings. Children add to this mental map as their awareness grows. From infancy on, developing theory of mind permeates everyday social interactions—affecting what and how children learn, how they react to and interact with other people, how they assess the fairness of an action, and how they evaluate themselves.

One-year-olds, for example, will look in their mother’s direction when faced with someone or something unfamiliar to “read” mother’s expression and determine whether this is a dangerous or benign unfamiliarity. Infants also detect when an adult makes eye contact, speaks in an infant-directed manner (such as using higher pitch and melodic intonations), and responds contingently to the infant’s behavior. Under these circumstances, infants are especially attentive to what the adult says and does, thus devoting special attention to social situations in which the adult’s intentions are likely to represent learning opportunities.

Other examples also illustrate how a developing theory of mind underlies children’s emerging understanding of the intentions of others. Take imitation, for example. It is well established that babies and young children imitate the actions of others. Children as young as 14 to 18 months are often imitating not the literal observed action but the action they thought the actor intended—the goal or the rationale behind the action (Meltzoff, 1999). Word learning is another example in which babies’ reasoning based on theory of mind plays a crucial role. By at least 15 months old, when babies hear an adult label an object, they take the speaker’s intent into account by checking the speaker’s focus of attention and deciding whether they think the adult indicated the object intentionally. Only when babies have evidence that the speaker intended to refer to a particular object with a label will they learn that word (Baldwin, 1993).

Babies can also perceive the unfulfilled goals of others and intervene to help them; this is called “shared intentionality.” Babies as young as 14 months old who witness an adult struggling to reach for an object will interrupt their play to crawl over and hand the object to the adult (Warneken & Tomasello, 2007). By the time they are 18 months old, shared intentionality enables toddlers to act helpfully in a variety of situations; for example, they pick up dropped objects for adults who indicate that they need assistance (but not for adults who dropped the object intentionally; Warneken & Tomasello, 2007). Developing an understanding of others’ goals and preferences and how to facilitate them affects how young children interpret the behavior of people they observe and provides a basis for developing a sense of helpful versus undesirable human activity that is a foundation for later development of moral understanding (Thompson & Newton, 2013).

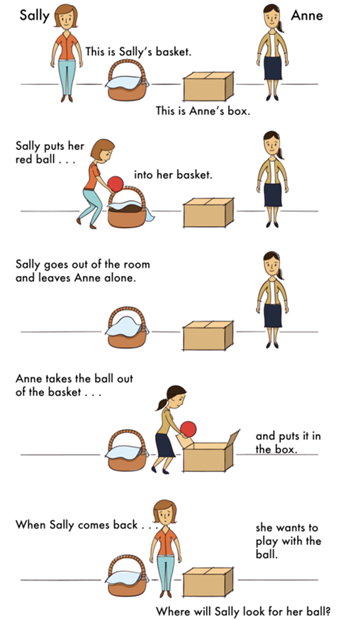

One common method for determining if an older child has reached this mental milestone is the false-belief task. The research in the area of false beliefs began with a clever experiment by Wimmer and Perner (1983), who noted the response of young children to what they called the “Sally-Anne Test.” During this test, the child is shown a picture story of Sally, who puts her ball in a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is out of the room, Anne comes along and takes the ball from the basket and puts it inside a box. The child is then asked where Sally thinks the ball is located when she comes back to the room. Is she going to look first in the box or in the basket? The right answer is that she will look in the basket because that is where she put it and thinks it is, but we have to infer this false belief against our own better knowledge that the ball is in the box. This is very difficult for children before the age of four because of the cognitive effort it takes. Three-year-old’s have difficulty distinguishing between what they once thought was true and what they now know to be true. They feel confident that what they know now is what they have always known (Birch & Bloom, 2003). Even adults need to think through this task (Epley et al., 2004). To be successful at solving this type of task the child must separate what he or she “knows” to be true from what someone else might “think” is true. The child must also understand that what guides people’s actions and responses are what they believe rather than what is reality. In other words, people can mistakenly believe things that are false and will act based on this false knowledge. Consequently, prior to age four children are rarely successful at solving such a task (Wellman et al., 2001).

The Role of Theory of Mind in Social Life

Put yourself in this scene: You observe two people’s movements, one behind a large wooden object, the other reaching behind him and then holding a thin object in front of the other. Without a theory of mind, you would neither understand what this movement stream meant nor be able to predict either person’s likely responses. With the capacity to interpret certain physical movements in terms of mental states, perceivers can parse this complex scene into intentional actions of reaching and giving (Baldwin & Baird, 2001); they can interpret the actions as instances of offering and trading; and with an appropriate cultural script, they know that all that was going on was a customer pulling out her credit card with the intention to pay the cashier behind the register. People’s theory of mind thus frames and interprets perceptions of human behavior in a particular way—as perceptions of agents who can act intentionally and who have desires, beliefs, and other mental states that guide their actions (Perner, 1991).

Not only would social perceivers without a theory of mind be utterly lost in a simple payment interaction; without a theory of mind, there would probably be no such things as cashiers, credit cards, and payment. Plain and simple, humans need to understand minds in order to engage in the kinds of complex interactions that social communities (small and large) require. And it is these complex social interactions that have given rise, in human cultural evolution, to houses, cities, and nations; to books, money, and computers; to education, law, and science. The list of social interactions that rely deeply on theory of mind is long; here are a few highlights.

- Teaching another person new actions or rules by considering what the learner knows or doesn’t know and how one might best make him understand.

- Learning the words of a language by monitoring what other people attend to and are trying to do when they use certain words.

- Figuring out our social standing by trying to guess what others think and feel about us.

- Sharing experiences by telling a friend how much we liked a movie or by showing her something beautiful.

- Collaborating on a task by signaling to one another that we share a goal and understand and trust the other’s intention to pursue this joint goal.

Watch It

Video 12.1 The Theory of Mind Test demonstrates several versions of the false belief test to assess the theory of mind in young children.

Autism and Theory of Mind

Another way of appreciating the enormous impact that theory of mind has on social interactions is to study what happens when the capacity is severely limited, as in the case of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In a landmark study, Baron-Cohen et al. (1985) reported that children with autism, who suffer from severe impairment in social interaction and communication, do not pass the false belief test. This seminal study inspired many follow-up studies, both in typically developing children and children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). The accumulation of the studies supports the proposal that children with ASD show atypical development of the capacity for theory of mind. The most consistent finding is that before the verbal mental age of 11 years, children with ASD do not pass various versions of the false belief test. Whereas typical 4-year-olds correctly anticipate others’ behavior based on the attribution of false belief, children with ASD, at the same mental age or even higher, incorrectly predict behavior based on reality without taking the other person’s epistemic states (e.g. knowledge and belief) into account (Happé, 1995). This result has been interpreted as evidence that children with ASD (with verbal skills equivalent to typically developing children of under 11 years) fail to represent others’ epistemic mental states, or at least fail to do so when others’ mental states are different from the child’s own. Based on these findings, some scientists suggested that the difficulty in social interaction and communication in ASD derives from impairment in theory of mind (mindblindness theory; Baron-Cohen, 1997).

However, there are two major problems in the standard false belief test. Firstly, it is a cognitively demanding test. To pass the test, a child has to remember the sequence of the presented event, correctly understand the experimenter’s question, and inhibit their initial response to answer the actual location of object (Birch and Bloom, 2003). Thus, it is possible that despite having the capacity to represent another person’s mental state, children fail the standard false belief test because of a weaker cognitive control or difficulty in pragmatic understanding. Secondly, individuals with ASD with higher verbal skills do pass the standard false belief test.

However, the qualitative difficulties in social interaction and communication persist even in these “high-functioning” individuals with ASD. For example, in an experimental setting, they still show subtle difficulties in understanding non-literal utterance (Happé, 1994) and faux-pas (Baron-Cohen et al., 1999), and fail to correctly infer complex mental states from photographs of eyes (Baron-Cohen et al., 1997) and from cartoon animations (Castelliet al., 2002).

Although to-date questions have arisen regarding the universality and uniqueness of theory-of-mind deficits in autism, and about how this hypothesis could explain early symptoms including restricted interests, or repetitive behaviors, studies repeatedly show reduced performance on tasks that assess theory of mind in ASD. Thus, theory of mind is still considered crucial for understanding social performance in ASD.

Check Your Understanding

one’s ability to think about other people’s thoughts and to perceive and interpret other people’s behavior in terms of their mental states

task used to determine if a child has theory of mind