Chapter 12: Play and Peer Relationships

What is Play?

What is Play?

“Play is behavior that looks as if it has no purpose,” says NIH psychologist Dr. Stephen Suomi. “It looks like fun, but it actually prepares for a complex social world.” Evidence suggests that play can help boost brain function, increase fitness, improve coordination and teach cooperation. Suomi notes that all mammals—from mice to humans—engage in some sort of play. His research focuses on rhesus monkeys. While he’s cautious about drawing parallels between monkeys and people, his studies offer some general insights into the benefits of play.

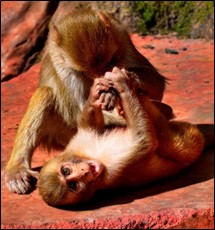

Figure 12.2 All mammals engage in some sort of play. These examples depict young monkeys playing, puppies playing, and toddlers playing.

Active, vigorous social play during development helps to sculpt the monkey brain. The brain grows larger. Connections between brain areas may strengthen. Play also helps monkey youngsters learn how to fit into their social group, which may range from 30 to 200 monkeys in 3 or 4 extended families. Both monkeys and humans live in highly complex social structures, says Suomi. “Through play, rhesus monkeys learn to negotiate, to deal with strangers, to lose gracefully, to stop before things get out of hand, and to follow rules,” he says. These lessons prepare monkey youngsters for life after they leave their mothers.

Play may have similar effects in the human brain. Play can help lay a foundation for learning the skills we need for social interactions. If human youngsters lack playtime, says Dr. Roberta Golinkoff, an infant language expert at the University of Delaware, “social skills will likely suffer. You will lack the ability to inhibit impulses, to switch tasks easily and to play on your own.” Play helps young children master their emotions and make their own decisions. It also teaches flexibility, motivation, and confidence.

Kids don’t need expensive toys to get a lot out of playtime. “Parents are children’s most enriching plaything,” says Golinkoff. Playing and talking to babies and children are vital for their language development. Golinkoff says that kids who talk with their parents tend to acquire a vocabulary that will later help them in school. “In those with parents who make a lot of demands, language is less well developed,” she says. The key is not to take over the conversation, or you’ll shut it down.

Types of Play

Play can be viewed as a spontaneous, voluntary, pleasurable, and flexible activity involving a combination of body, object, symbol use, and relationships. In contrast to games, play behavior is more disorganized, and is typically done for its own sake (i.e., the process is more important than any goals or endpoints). Recognized as a universal phenomenon, play is a legitimate right of childhood and should be part of all children’s life. Between 3% to 20% of young children’s time and energy is spent in play, and more so in a non-impoverished environment. Although play is an important arena in children’s life associated with immediate, short-term, and long-term term benefits, cultural factors influence children’s opportunities for free play in different ways. Over the last decade, there has been an ongoing reduction of playtime in favor of educational instructions, especially in modern and urban societies. Furthermore, parental concerns about safety sometimes limit children’s opportunities to engage in playful and creative activities. Along the same lines, the increase in commercial toys and technological developments by the toy industry has fostered more sedentary and less healthy play behaviors in children. Yet, play is essential to young children’s education and should not be abruptly minimized and segregated from learning. Not only does play help children develop pre-literacy skills, problem-solving skills, and concentration, but it also generates social learning experiences, and helps children to express possible stresses and problems.

Throughout the preschool years, young children engage in different forms of play, including social, parallel, object, sociodramatic, and locomotor play. The frequency and type of play vary according to children’s age, cognitive maturity, physical development, as well as the cultural context. For example, children with physical, intellectual, and/or language disabilities engage in play behaviors, yet they may experience delays in some forms of play and require more parental supervision than typically developing children.

Social play is usually the first form of play observed in young children. Social play is characterized by playful interactions with parents (up to age 2) and/or other children (from two years onwards). In spite of being around other children of their age, children between 2 to 3 years old commonly play next to each other without much interaction (i.e., parallel play). As their cognitive skills develop, including their ability to imagine, imitate, and understand others’ beliefs and intents, children start to engage in sociodramatic play. While interacting with same-age peers, children develop narrative thinking, problem-solving skills (e.g., when negotiating roles), and a general understanding of the building blocks of the story. Around the same time, physical/locomotor play also increases in frequency. Although locomotor play typically includes running and climbing, play fighting is common, especially among boys aged three to six. In contrast to popular belief, play fighting lacks intent to harm either emotionally or physically even though it can look like real fighting. In fact, during the primary school years, only about 1% of play-fighting turn into serious physical aggression. Nevertheless, the effects of such play are of special concern among children who display antisocial behavior and less empathic understanding, and therefore supervision is warranted.

In addition, to vary according to the child’s factors, the frequency, type, and play area are influenced by the cultural context. While there are universal features of play across cultures (e.g., traditional games and activities and gender-based play preferences), differences also exist. For instance, children who live in rural areas typically engage in more free play and have access to larger spaces for playing. In contrast, adult supervision in children’s play is more frequent in urban areas due to safety concerns. Along the same lines, cultures value and react differently to play. Some adults refrain from engaging in play as it represents a spontaneous activity for children while others promote the importance of structuring play to foster children’s cognitive, social and emotional development.

If play is associated with children’s academic and social development, teachers, parents, and therapists are encouraged to develop knowledge about the different techniques to help children develop their play-related skills. However, in order to come up with best practices, further research on the examination of high-quality play is warranted.

From the available literature on play, it is recommended to create play environments to stimulate and foster children’s learning. Depending on the type of play, researchers suggest providing toys that enhance children’s:

- motor coordination (e.g., challenging forms of climbing structure);

- creativity (e.g., building blocks, paint, clay, play dough);

- mathematic skills (e.g., board games “Chutes and Ladders” – estimation, counting, and numeral identification);

- language and reading skills (e.g., plastic letters, rhyming games, making shopping lists, bedtime story books, toys for pretending).

Other recommendations have been suggested in order to enhance literacy skills in children. Researchers suggest that setting up literacy-rich environments, such as a “real restaurant” with tables, menus, name tags, pencils, and notepads, are effective to increase children’s potential in early literacy development. Educators are also encouraged to adopt a whole child approach that targets not only literacy learning but also the child’s creativity, imagination, persistence, and positive attitudes in reading. Teachers and educators should also make a parallel between what can be learned from playful activities and the academic curriculum in order for children to understand that play allows them to practice and reinforce what is learned in class. However, educators should ensure that a curriculum based on playful learning includes activities that are perceived as playful by children themselves rather than only by the teachers. Most experts agree that a balanced approach consisting of periods of free play and structured/guided play should be favored. Indeed, adults are encouraged to give children space during playtime to enable the development of self-expression and independence in children with and without disabilities. Lastly, parents of children with socio-emotional difficulties are encouraged to receive play therapy training to develop empathic understanding and responsive involvement during playtime.

Check Your Understanding