Psychological theories of language learning differ in terms of the importance they place on nature and nurture. Remember that we are a product of both nature and nurture. Researchers now believe that language acquisition is partially innate and partially learned through our interactions with our linguistic environment (Gleitman & Newport, 1995).

Learning Theory

Perhaps the most straightforward explanation of language development is that it occurs through the principles of learning, including association and reinforcement (Skinner, 1957). Additionally, Bandura & Walters (1977) described the importance of observation and imitation of others in learning language. There must be at least some truth to the idea that language is learned through environmental interactions or nurture. Children learn the language that they hear spoken around them rather than some other language. Also supporting this idea is the gradual improvement of language skills with time. It seems that children modify their language through imitation and reinforcement, such as parental praise and being understood. For example, when a two-year-old child asks for juice, he might say, “me juice,” to which his mother might respond by giving him a cup of apple juice.

However, language cannot be entirely learned. For one, children learn words too fast for them to be learned through reinforcement. Between the ages of 18 months and 5 years, children learn up to 10 new words every day (McMurray, 2007). More importantly, language is more generative than it is imitative. Language is not a predefined set of ideas and sentences that we choose when we need them, but rather a system of rules and procedures that allows us to create an infinite number of statements, thoughts, and ideas, including those that have never previously occurred. When a child says that they “swimmed” in the pool, for instance, they are showing generativity. No adult speaker of English would ever say “swimmed,” yet it is easily generated from the normal system of producing language.

Other evidence that refutes the idea that all language is learned through experience comes from the observation that children may learn languages better than they ever hear them. Deaf children whose parents do not speak ASL very well nevertheless are able to learn it perfectly on their own, and may even make up their own language if they need to (Goldin-Meadow & Mylander, 1998). A group of deaf children in a school in Nicaragua, whose teachers could not sign, invented a way to communicate through made-up signs (Senghas, Senghas, & Pyers, 2014). The development of this new Nicaraguan Sign Language has continued and changed as new generations of students have come to the school and started using the language. Although the original system was not a real language, it is becoming closer and closer every year, showing the development of a new language in modern times.

Nativism

The linguist Noam Chomsky is a believer in the nature approach to language, arguing that human brains contain a Language Acquisition Device that includes a universal grammar that underlies all human language (Chomsky, 1965). According to this approach, each of the many languages spoken around the world (there are between 6,000 and 8,000) is an individual example of the same underlying set of procedures that are hardwired into human brains. Chomsky’s account proposes that children are born with a knowledge of general rules of syntax that determine how sentences are constructed. Language develops as long as the infant is exposed to it. No teaching, training, or reinforcement is required for language to develop as proposed by Skinner.

Although there is general agreement among psychologists that babies are genetically programmed to learn language, there is still debate about Chomsky’s idea that there is a universal grammar that can account for all language learning. Evans and Levinson (2009) surveyed the world’s languages and found that none of the presumed underlying features of the language acquisition device were entirely universal. In their search they found languages that did not have noun or verb phrases, that did not have tenses (e.g., past, present, future), and even some that did not have nouns or verbs at all, even though a basic assumption of a universal grammar is that all languages should share these features.

Sensitive Periods

Anyone who has tried to master a second language as an adult knows the difficulty of language learning. Yet children learn languages easily and naturally. Children who are not exposed to language early in their lives will likely never learn one. Case studies, including Victor the “Wild Child,” who was abandoned as a baby in France and not discovered until he was 12, and Genie, a child whose parents kept her locked in a closet from 18 months until 13 years of age, are (fortunately) two of the only known examples of these deprived children. Both of these children made some progress in socialization after they were rescued, but neither of them ever developed complex language abilities (Rymer, 1993). This is also why it is important to determine quickly if a child is deaf, and to communicate in sign language immediately. Deaf children who are not exposed to sign language during their early years will likely never learn the complexity of language (Mayberry et al., 2002). The concept of sensitive periods highlights the importance of both nature and nurture for language development.

Learning a Second Language

Children are incredibly good at learning language. But as we age, we stop making as many new connections between neurons. Our brains are less sensitive to the experiences we have in our everyday lives. While we can still learn new things as adults, we will likely have to try harder, or repeat the task more times than we would if we were learning the same thing as a child.

This doesn’t mean that we can’t learn a second language as adults. We can always learn new things. It just means that it will be harder for us. This is partly due to how our brains develop. When a child is young, connections form at a rapid rate, and the brain is particularly sensitive to new experiences.

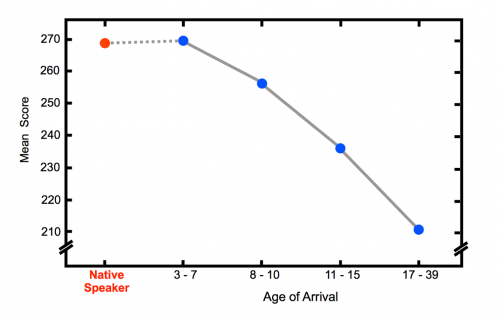

Research shows a close relationship between the age of exposure to a language and proficiency in that language—peak proficiency is far more likely for those exposed to that language in early childhood (Newport et al., 2001). This is especially pertinent for learning a second language. A seminal study examined second language acquisition in native Chinese or Korean speakers who moved to the United States and learned English at different ages (Johnson & Newport, 1989). Results indicated that children who began learning the second language (English) before age 7 were able to reach proficiency akin to native English speakers; children arriving between age 7 and puberty were less proficient; and after puberty, an individual’s second language proficiency is likely to remain low. These findings support a brain-maturation account, such that the ability to learn languages gradually declines and ultimately flattens as the brain matures. Importantly, this is not to say that learning a second language is impossible after brain maturation; but lower neuroplasticity after this sensitive period contributes to slower second language learning. The ability to learn second languages throughout life, albeit more slowly with age, demonstrates that second language acquisition reflects a sensitive rather than critical developmental period. In summary, children may be better equipped to learn a second language during this sensitive period due to the heightened neuroplasticity.